- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How I became a ‘Swiftie’

For years, I loved to hate Taylor Swift.

My tweets about her were mean. There was bad blood. I couldn’t shake it off. Why? Gossip about the musician’s relationship breakups colored my perception of her. My inner music snob chafed at what I perceived as a gimlet-eyed pursuit of all-conquering stardom.

In 2022, Ms. Swift is bigger than ever. If Ticketmaster’s servers melt down today, it’ll be because tickets just went on sale for her 2023 stadium tour. Last month, the megastar’s 10th album, “Midnights,” became Spotify’s most-streamed album in a single day. It sold over a million vinyl copies in its first week. Songs from “Midnights” occupied all 10 top spots on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

Ms. Swift’s success was anathema to me. I always used the mute button whenever I came across her music. Then two years ago, a friend of mine came over to my house and implored me to stream a song Ms. Swift had released, “The Last Great American Dynasty.” It’s a Gatsby-esque tale about the uproarious life of Rebekah Harkness, an early 20th-century socialite who lived in an ocean-facing mansion in Rhode Island. “There goes the most shameless woman this town has ever seen,” sings Ms. Swift. “She had a marvelous time ruinin’ everything.”

Then comes the lyric plot twist. Ms. Swift breaks the fourth wall and reveals that she is now the owner of that historic home. We realize that the song isn’t just about people throwing shade at Ms. Harkness. It’s a meta commentary about how people perceive the songwriter.

I was floored by Ms. Swift’s masterful songwriting. I glimpsed the person beyond the persona I’d built up in my mind. I had judged Ms. Swift. I hadn’t truly listened to her. Were there other areas of my life in which I’ve had similar blindspots?

“Midnights” is a conceptual album about things that keep Ms. Swift awake at night. The album’s lyrics are more self-reflective (and sweary) than recent releases. Its downtempo electronic sound is the latest chameleonic shift in a bold career that has already spanned country, pop, and folk. On October 21, Ms. Swift convened a novel listening party for it. At midnight, millions of people logged onto streaming services for that rarest thing in pop culture: a vast shared communal experience. And I was among them, proud to be a fellow Swiftie.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

After midterms, will GOP seek to move on from Trump?

Will the midterm results convince Republicans to move on from former President Donald Trump? Or will he assert his hold on the party once more?

Right now, former President Donald Trump’s grip on the Republican Party appears as tenuous as it’s ever been. Most of his marquee candidates in battleground states lost in last week’s midterms, in what political commentators have interpreted as a rebuke to the MAGA brand.

Mr. Trump also remains under investigation, facing perhaps the greatest legal jeopardy of his career. And polls suggest Republican voters may be wearying of him, with Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis pulling ahead in recent surveys ranking potential 2024 contenders.

True to form, the former president has responded to this moment of weakness by going on the offensive. He is calling the Nov. 8 election a “very big victory,” trumpeting the likely GOP takeover of the House. He has also turned up the heat on potential challengers for the GOP presidential nomination.

Previous predictions of Mr. Trump’s political demise have all proved premature, and even many of his critics say it would be unwise to bet against him. He has survived scandals, impeachments, twice losing the popular vote, and more.

“After Jan. 6, Republicans could have taken this man down – and they didn’t,” says GOP strategist Scott Jennings, referring to the attack on the U.S. Capitol. “If someone is weak, that’s the time to move,” he adds.

After midterms, will GOP seek to move on from Trump?

Is the GOP still the party of Donald Trump?

In the wake of their disappointing midterm results – and as the former president prepares for a “big” announcement, with expectations that he will make his 2024 bid official tonight – Republicans are once again wrestling with the same existential question that has consumed the party off and on for the past six years.

Right now, Mr. Trump’s grip on his party appears as tenuous as it’s ever been. Most of his marquee candidates in battleground states lost last week, and those who won often lagged mainstream Republicans on the ticket. Across the political spectrum, commentators have interpreted the election as a sharp rebuke to the MAGA brand, calling the former president a drag on the GOP ticket and a gift to Democratic turnout.

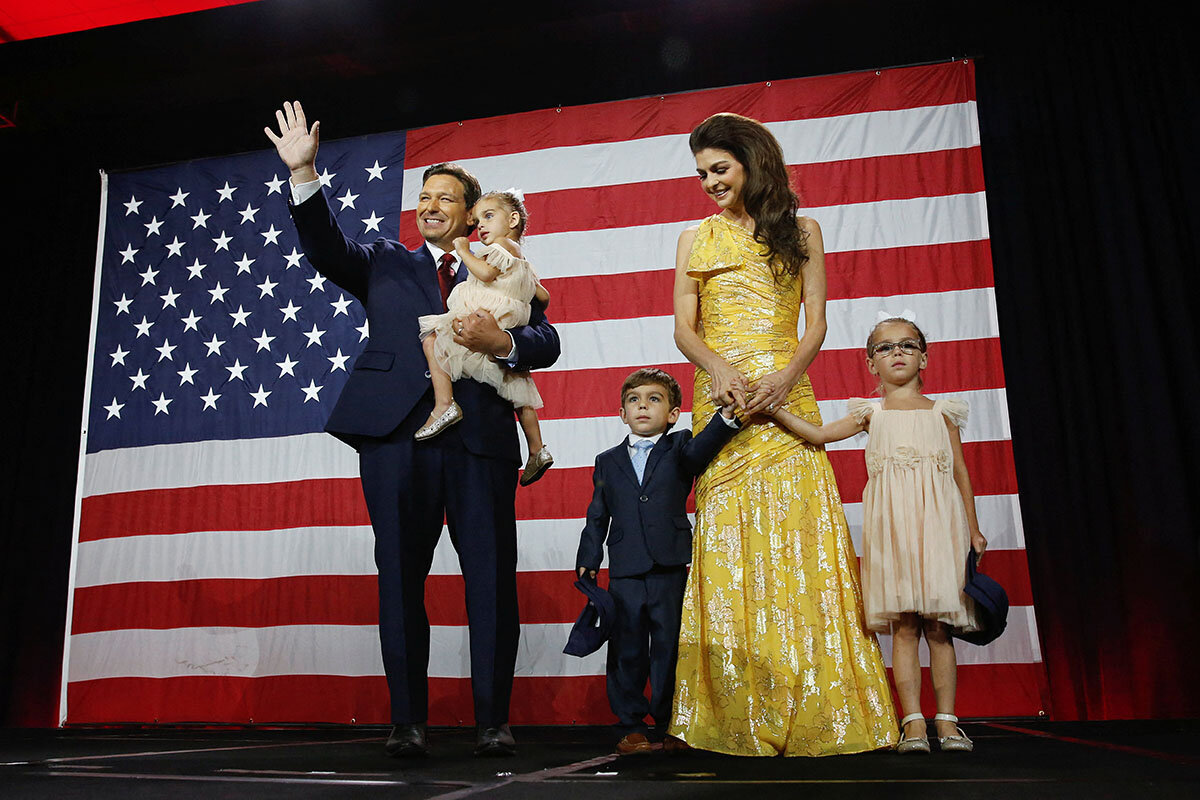

Mr. Trump also remains under investigation, facing perhaps the greatest legal jeopardy of his career, over everything from the classified documents taken from the White House to his business dealings in New York. And polls suggest many Republican voters may be wearying of him. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, whose resounding reelection victory last week led the conservative, Murdoch-owned New York Post to dub him “DeFuture,” has pulled ahead in several recent surveys ranking potential 2024 contenders.

True to form, the former president has responded to this apparent moment of weakness by going on the offensive. He is calling the Nov. 8 election a “very big victory” for him and his allies, trumpeting the likely GOP takeover of the House, and attributing the failure to capture the Senate to “very obvious CHEATING” (a charge that virtually none of his endorsees have echoed).

Notably, he has also turned up the heat on potential challengers for the GOP presidential nomination, unloading in particular on Governor DeSantis, whom he has labeled “DeSanctimonius.”

The attacks make clear what awaits anyone who stands in Mr. Trump’s way, highlighting his instinctive ability to isolate and defenestrate detractors while keeping a tight grip on the base.

Previous predictions of Mr. Trump’s political demise have all proved premature. Even many of his critics say it would be unwise to count him out. He has survived scandals, two impeachments, and twice losing the popular vote. Party leaders could easily have turned against him after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, or particularly after the deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021 – but wound up falling into line instead. Indeed, it was Mr. Trump’s Republican critics, such as Reps. Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger, who ultimately paid a political price.

“After Jan. 6, Republicans could have taken this man down – and they didn’t,” says GOP strategist Scott Jennings, a former adviser to President George W. Bush. “If someone is weak, that’s the time to move,” he adds.

The post-election math

One factor that could make this particular moment of weakness different is that it’s mostly about the math. In politics, power ultimately hinges on winning – and Mr. Trump’s credibility as a winner appears seriously tarnished.

Heading into the midterms, the former president was expected to use the results as a springboard for a presidential run that would clear the field. He even teased an announcement on the eve of Election Day, as predictions of a “red wave” grew. But the poor showing for his candidates in battleground races, from Pennsylvania to New Hampshire to Arizona, ultimately costing Republicans a chance to flip the Senate, tore up that playbook.

In Florida, by contrast, Governor DeSantis cruised to reelection, including in Latino districts around Miami that were previously Democratic strongholds. His success is stoking some Republican dreams of a DeSantis ticket in 2024 that could unite the party – and cast Mr. Trump into the past.

“I think the tables have been turned,” says Jerry Sickels, a Republican strategist in New Hampshire who worked on Mr. Trump’s 2016 campaign.

Indeed, a number of prominent Republicans from battleground states are now saying the quiet part out loud.

Former House Speaker Paul Ryan told a Wisconsin TV station that Mr. Trump was “a drag on the ticket” and predicted he wouldn’t capture the nomination in 2024. “We want to win the White House and we know with Trump we’re so much more likely to lose,” he said.

In Pennsylvania, where Trump-backed Dr. Mehmet Oz lost a competitive Senate race to Democrat John Fetterman, retiring Republican Sen. Pat Toomey predicted it was just a matter of time before Mr. Trump steps aside. “I think Donald Trump’s influence gradually but steadily declines, and I think it accelerates after the [electoral] debacle that he’s responsible for to some degree,” Senator Toomey told The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Republicans in Michigan are also blaming Mr. Trump for a Democratic sweep of statewide offices and the state Legislature. In a memo, GOP officials complained that party donors balked at funding far-right Trump allies, including gubernatorial candidate Tudor Dixon, who lost by double digits to Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

Yet the vast majority of Republican lawmakers have been holding fire. Those with presidential ambitions, or even an upcoming reelection race, seem wary of angering Mr. Trump and his many adoring fans, who can swing a primary. This is a familiar pattern, one that Mr. Trump knows how to exploit, says David Drucker, author of “Trump’s Shadow: The Battle for 2024 and the Future of the GOP.”

“You need to take the fight to him,” he says. “Just waiting for him to go away will never work.”

This same goes for the former president’s supporters who prize his pugnacious style, says Mr. Drucker, a reporter at the Washington Examiner. “The only thing that will show Republican voters that you’re a fighter and leader is to take on Trump as he takes on everyone else,” he says.

Several GOP contenders have been seeding the ground for 2024 by visiting early primary states and endorsing and raising money for candidates. Among them are former Trump administration officials like Nikki Haley; Mike Pompeo; and Mike Pence, Mr. Trump’s former vice president, who has a new book out. All have been treading carefully when it comes to the former president.

So far, the biggest buzz among GOP donors and activists surrounds Governor DeSantis, whose culture-war exploits have become a fixture on Fox News. On Tuesday, the Florida governor responded to Mr. Trump’s attacks with a not-so-subtle jab, telling reporters to “check out the scoreboard.”

The fact that a credible replacement is waiting in the wings could also make this moment different from all of Mr. Trump’s previous stumbles, says Mr. Jennings. “Republicans can see the next lily pad,” he says.

“There’s enough blame to go around”

By announcing his run so early, Mr. Trump appears to be looking to head off his likely competitors, pressuring GOP officials and donors to fall into line. His timing also may be geared to the legal peril he faces on several fronts, since many experts believe it becomes more politically treacherous to indict him once he’s a presidential candidate-in-waiting.

Already, the former president is attracting public statements of support: Rep. Elise Stefanik, a Republican in House leadership, has endorsed him as presidential candidate even before he declares.

One frustration for Republicans was not just that Trump-endorsed candidates flopped last Tuesday, but that Mr. Trump actively dissuaded better politicians from running, says Robert Blizzard, a GOP pollster. Popular Republican governors in New Hampshire and Arizona opted not to run for the Senate, and that hurt the party, he says. “Voters are rewarding serious, experienced people,” he says.

Mr. Blizzard notes that Electoral College victory in 2024 will hinge on the same battleground states that were in the midterm spotlight. “A Republican path to the White House in 2024 goes through Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada,” he says. “If we don’t win those states, we’re going to be shut out.”

Still, Mr. Trump’s defenders argue that what the midterms really demonstrated was that Republicans need him on the ballot, with his unique ability to turn out disaffected voters. They also blame GOP leaders in Congress for failing to prioritize the right seats and note that moderate GOP candidates also lost toss-up midterm races.

Fran Wendelboe, a Republican former state legislator in New Hampshire, believes her party has been too quick to blame Mr. Trump for its midterm defeats. “There’s enough blame to go around for everyone,” she says.

But Ms. Wendelboe is concerned about Mr. Trump’s electability in 2024. She says she’s ready to move on from the man she calls “a great president” and who she believes was unfairly persecuted in office.

Mr. Trump needs to “think not so much about what’s best for Donald Trump but what’s best for the country,” she says.

As world grows hotter, farmers race to innovate

A food crisis is felt most keenly now in the Horn of Africa, but climate change is affecting food security worldwide. Farmers are finding new ideas, and sharing old ones, to meet the challenges.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Ahmed Ellali Contributor

-

Sandra Cuffe Contributor

In Guatemala, farmers are setting up “living fences” around fields, creating a buffer of roots to protect their soil during increasingly strong rainy seasons.

In Jordan, local Bedouin communities and authorities are pioneering resilient desert agriculture in a region that has been hit by longer and more intense heat waves.

And in Burkina Faso, William Kwende has been working to revolutionize shea butter production – by substituting renewable energy for traditional wood-burning methods that result in deforestation.

These examples symbolize how farmers around the world are trying to adapt in the face of growing climate-related challenges. Russia’s war in Ukraine has also pushed up global energy costs and crimped supplies of fertilizer as well as grain.

In Somalia and Kenya alone, drought threatens to push millions into food poverty and starvation.

At the COP27 climate summit in Egypt, a newly announced initiative aims to expand sustainable food production through knowledge sharing and improved access to finance.

“We are heading to crop failure in many parts of the world in the next six months,” warns Mr. Kwende. “Real change will be measured by specific indicators. Commitments and words are no longer enough without action.”

As world grows hotter, farmers race to innovate

In Guatemala, farmers are setting up “living fences” around fields, creating a buffer of roots to protect their soil during increasingly strong rainy seasons.

In Jordan, local Bedouin communities and authorities are pioneering resilient desert agriculture in a region that has been hit by longer and more intense heat waves.

And in Burkina Faso, William Kwende has been working to revolutionize shea butter production – by substituting renewable energy for traditional wood-burning methods that result in deforestation.

He has introduced an approach with 100% renewable energy, self-sustaining biomass burners, and a closed water system, which is curbing emissions while also reducing crop losses.

At a time of global strain on food production, including an emerging famine in parts of East Africa, his story symbolizes the potential for using innovation to adapt to a changing climate. The business Mr. Kwende co-founded, called Serious Shea, is designed to promote reforestation and to secure fairer wages and independence for the local women at the heart of the process.

A key part of the innovation: Serious Shea’s eco-processing centers transform shea tree biomass into natural biofertilizer and biochar, enriching soils that are at risk of desertification and reducing reliance on expensive imported chemical fertilizers.

“People talk about water and food imports, but when you talk about food crises and adaptation, fertilizer is at the heart of it,” Mr. Kwende tells the Monitor on the sidelines of COP27, this year’s global climate summit, at Sharm el-Sheikh. “When it comes to reducing waste, cost, and carbon, fertilizer is key to this transition.”

Across the globe, innovative ideas like that are greatly needed. Extreme weather events are affecting the vital sector of food production – with the shifts especially hard for Indigenous communities and small-scale farmers. In Peru, rising temperatures have upended the livelihoods of alpaca farmers. In Pakistan, massive floods have sidelined several million acres from crop production. In Somalia and Kenya alone, drought threatens to push millions into food-poverty and starvation.

The challenges have been exacerbated by Russia’s war in Ukraine, affecting global energy costs and supplies of grain, flour, and fertilizer.

All this has made saving and transforming the way the world feeds itself a pressing issue. With its own farmers suffering losses amid intense heat waves and drop in Nile waters, atop the food-security crisis in the Horn of Africa, Egypt has placed agriculture front and center to an unprecedented degree at the current “conference of parties,” or COP.

“All of these converging crises are making people realize that food is something that we absolutely need to pay attention to in a climate context in the next few years and decades if we want to reach a 1.5 degree [C] future, create a sustainable future, ensure food security, livelihoods and promote biodiversity,” says Chantal Wei-Ying Clément, deputy director of the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES-Food).

“Food systems are so cross-cutting that if you are not dealing with food systems, you are missing a huge piece of the puzzle.”

Seeking water, from Mexican orchards to the Andes

Agriculture experts say some of the solutions will involve mass-produced technologies such as battery-operated farm equipment. But it will also involve the rise and transfer of hundreds of local, homegrown solutions emerging across the world, many of which advocates say can cut carbon, improve resilience, and be replicated elsewhere.

In Mexico, where last summer eight of 32 states experienced moderate to extreme drought and where half of all municipalities in the country face water shortages, some farmers turn 2-liter soda bottles upside down over saplings to capture morning dew or dig holes and line them with organic materials like leaves, to retain rainfall around young trees.

To the south in Peru, Alina Surquislla’s family has never seen anything like the current effects of rising temperatures in their three generations of alpaca herding.

“There’s no water; the grass is turning yellow and disappearing for lack of rain,” says Ms. Surquislla. Alpacas are dying out at worrying rates. Speaking over a Wi-Fi satellite connection while walking at nearly 16,000 feet above sea level in the Apurimac region, she says, “More and more the feeling is that there is nowhere to escape.”

For now, she says the answer for herders is to go to higher and higher elevations in search of water and grazing.

New experiments, old traditions

Water is also scarce in Jordan. There, local Bedouin communities and authorities are scaling up pioneering desert agriculture in Al Mudawara, a border region near Saudi Arabia that has been hit by longer and more intense heat waves in the past few years.

Since 2019, under a directive by Jordan’s King Abdullah, each family in the area has been tending to 6-acre plots of yellow corn and green onions, watered from an underground aquifer. The crops have proved resilient to more frequent 120 degree F temperatures, sprouting up into green waves amid reddish desert sands that have not been utilized for agriculture in modern history.

Now over 4,000 acres of corn stalks stand 3 feet high and onions sprout in Al Mudawara. These provide alternative sources of income and living for Bedouin families, many of whom have been forced to abandon traditional camel shepherding due to the mounting costs of imported animal feed.

“It has been a successful project. This is encouraging a lot of young people to go into agriculture,” says Abu Fahed al Huweiti, former director of the Al Mudawara Agricultural Cooperative that has steered the project. “It has given a new hope for people here.”

Other solutions date back centuries.

In Tunisia, amid the lush fig and olive groves of Djebba, clinging to the tops of the Gorraa mountain, farmers continue a centuries-old terraced farming that has helped them cope with massive heat waves and drought that has hit much of Tunisia.

A series of cement-lined canals crisscross down the hill through the terraced farms, carrying water from natural springs fed by winter’s snow to groves of figs, pomegranates, quince, and olives on a rotating basis of collective water-sharing.

This ingenious method of traditional Berber farming provides timed irrigation of entire land plots, allowing local farmers to grow not only trees but also herbs and diverse flora and fauna, feeding livestock and chickens – all from the same measured water delivery.

It is this biodiversity and careful water management that has made Djebba the most resilient of Tunisia’s farming regions.

“We in Djebba keep using the same old techniques because it has shown success. It is an inherited model of coexistence and represents the ideal use of available water resources,” says Fawzi Djebbi, Djebba farmer, activist, and head of the annual Djebba Fig Festival.

“Here we use the water as a collective resource from the mountains. This water belongs to all of us.”

One key need: transferring best practices

Knowledge- and expertise-sharing has also been critical to speeding up farmers’ adaptation to the pummeling effects of severe weather events.

The CCDA, an Indigenous and small farmers movement for land rights and rural development in Guatemala, is working with many of their 1,300 affiliated communities around new techniques to help farmers adapt. This year’s rainy season has been one of the longest and heaviest this century, for example.

One technique is planting trees and plants with deep roots around crop plots. The plants are a buffer against erosion, provide shade during the hot and dry season, and sometimes include edible plants as well.

“Setting up living fences helps the conservation of the soil, among other things, for people to keep producing,” says CCDA coordinator Marcelo Subac. “The farmers we accompany and others who have … implemented changes see the difference.”

Global organizations are seeking to spread helpful practices and information.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has been teaming up with Vodafone to get early warning systems and messages to rural farmers across Africa to better prepare for projected climate trends and to provide advice on mitigation measures.

Other information-sharing projects include smartphone apps Mufeed and Muzaraa, which alert farmers in Egypt and Jordan, respectively, on more modern agricultural practices, weather warnings, and tips to become more environmentally sustainable.

At COP27, calls for action

The importance of farm adaptations worldwide is clear enough on the basis of food security alone. It is also a climate action imperative. Agriculture is responsible for about 20% of greenhouse gases, and currently only 3% of climate financing for adaptation goes to agriculture.

This year’s climate summit included the first designated food and agriculture day in the 27-year history of the conference – an event Saturday where Mr. Kwende from Burkina Faso participated.

Behind the scenes, Egypt’s veteran diplomats have been pushing for increased climate financing to the adaptation of agriculture in developing countries to make them more resilient and sustainable.

In its key policy as chairing the presidency of COP27, Egypt announced last week the Sharm El Sheikh Adaptation Agenda, an ambitious plan to scale up climate resilient agriculture that increases yields by 17% and reduces farm greenhouse gas emissions by 21% without increasing the expansion of agricultural lands globally by 2030.

It also aims to halve food production loss and per capita waste, boost alternative proteins to equal 15% of the global meat and seafood market, and extend smart early warning systems to reach 3 billion people.

On Saturday, Egypt and the FAO announced the Food and Agriculture for Sustainable Transformation (FAST) initiative to develop sustainable farming and food production by improving access to finance, knowledge-sharing, and policy support with U.N. agencies acting as facilitators between developing countries and international finance institutions and donors.

“Words are no longer enough”

One glaring shortfall remains amid the rising focus on local solutions and knowledge-sharing: funds.

The Sharm El Sheikh Adaptation plan requires an estimated $140 billion to $300 billion in combined public and private financing per year.

However, the international community has yet to live up to the $100 billion in global climate financing commitment agreed to in the 2015 Paris accords, a number widely recognized as a tiny fraction of what is now needed to help communities face and adapt to the current effects of climate change.

Some lending bodies, such as the Dutch entrepreneurial development bank FMO, have already started to back local farming innovations and climate-resilient and climate-sustainable farming in the developing world.

However, Egyptian and other African negotiators warn that some aspects of adaptive agriculture – such as expanding renewable energy or improving water infrastructure – are not profitable ventures on their own and will not attract investors or lenders looking for a return.

Meanwhile, the major presence of big agriculture and large food corporations at COP27 – speaking at panel events and hobnobbing with government ministers – is raising fears among environmental experts that the discussion over adaptive agriculture is being steered toward expensive high-tech innovation that only modestly cuts carbon and is monopolized by big ag rather than true agroecology and local, sustainable, and enduring solutions.

One point of broad agreement: With famine, drought, and geopolitics colliding, world governments and finance institutions must act fast.

“We are heading to crop failure in many parts of the world in the next six months,” warns Mr. Kwende of Serious Shea. “Real change will be measured by specific indicators. Commitments and words are no longer enough without action.”

Taylor Luck reported from Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt; and Al Mudawara, Jordan. Whitney Eulich reported from Mexico City; Ahmed Ellali from Djebba, Tunisia; and Sandra Cuffe from Guatemala City.

Even as shells fall, Ukraine’s deminers work to make the land safe

Even when combat ends in Ukraine’s fields and towns, danger still lurks in the form of mines and unexploded ordnance. Ukrainian deminers are making former battlefields safe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Ukrainian soldiers retook the regional capital of Kherson on Friday, and deminers got to work immediately. Just a day later, they had already removed almost 2,000 explosive devices. And their job was just beginning.

For Ukraine’s deminers working all across the country, the task is a daunting one. A life-and-death job even when a war isn’t going on, demining demands not just technical skills, but intuition, focus, calm, and courage. And as Ukrainians drive back Russian forces and civilians try to rebuild shattered lives, the work that the deminers do is crucial to ensuring a safer future.

“Mines are perfect soldiers,” says Oleksandr Kotvytskyy, regional supervisor for The Halo Trust, an international demining organization working in several regions of Ukraine. “They can lie in wait for years and then strike.”

He calculates that one year of war creates about 10 years of demining work. The territories of Ukraine where explosive ordnance has been reported encompass nearly 54,000 square miles – an area the size of the state of New York.

“The biggest priority is that we do something for our land and country,” says Anna Davydovska, a deminer working in Bucha. Her adult son is also a deminer. “I know that my family and I are 100% useful to our country.”

Even as shells fall, Ukraine’s deminers work to make the land safe

Body armor and a first aid kit are critical gear for Oleksandr Kozachenko as he finds and defuses unexploded ordnance in this recently liberated town in Ukraine’s Donetsk region. But just as essential to survival in his high-risk job, he says, is his good luck charm: a tiny, fading-purple teddy bear given to him by his niece.

“I am alive, my limbs are in place – so yes, I feel lucky,” says Mr. Kozachenko with a broad smile that passes quickly. October took a heavy toll on Ukraine’s demining efforts and teams. He knows of at least three deminers who have been killed and another two wounded while working in territory recently regained from Russian forces. Among the fatalities was a friend and colleague: Kurilov, or “Chili” for short.

“It’s the nature of the job,” Mr. Kozachenko says. “You can’t be safe.”

But making Lyman safe was the goal for Mr. Kozachenko and his 16 colleagues as they worked to clear the streets of explosives in late October, after the town had been liberated from Russian occupation. Lyman is but a small corner of what experts say will be an epic, decades-long task of clearing Ukraine of land mines and other unexploded war materiel.

For Ukraine’s deminers working all across the country, the task is a daunting one. A life-and-death job even when a war isn’t going on, demining demands not just technical skills and training, but intuition, focus, calm, and courage. And as Ukrainians drive back Russian forces and civilians try to rebuild shattered lives, the work that the deminers do is crucial to creating a safer future.

An urgent, painstakingly slow job

The territories of Ukraine where explosive ordnance have been reported encompass nearly 54,000 square miles – an area the size of the state of New York in the United States, or Greece in Europe. That means experts will need to survey these areas to assess the level of contamination – a painstakingly slow process even in peacetime. In the city of Kherson, liberated last Friday, such surveys have just begun, and almost 2,000 explosives have already been removed, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said in a televised address Saturday.

But in Lyman and its surrounding villages – once home to about 45,000 people before the area came under Russian control – people started to return once the area was liberated, primarily to repair battle-scarred roofs and windows before the season’s heavy rains give way to snow.

The approach of winter, when clearance work becomes impossible, creates a sense of urgency among the deminers. They work from dawn to dusk, taking only short breaks, so that electricians can restore power to strategic locations in the city. Their eyes are quick to spot the silver shine of unexploded rifle grenades lurking in the grass. Booby traps and tripwire mines worry them the most; one such trap killed a whole sounder of wild boars running in the forest, providing a ghastly reminder of the danger.

“The area is very polluted by bombs, shrapnel, and rocket remains,” says Vitaliy Vorona, tasked with overseeing the work of the state emergency services in Lyman. He sleeps at the fire station that the deminers use as their base because the windows and door in his home are gone. Pro-Russian graffiti sprayed on walls and bus stops have been crossed out and replaced with a simple question: How could you?

“Fortunately rockets are landing less frequently now,” says Mr. Vorona, knocking on his wooden desk to ward off a change in fortune. “Unfortunately, I think it will take over a year to clear this whole area.”

“I never imagined I would do so much demining”

The demand for demining experts is so high that crash courses have been launched, teaching the appropriate skills in double-quick time.

For most on the team in Lyman, demining is a job they took on many years before Russian troops invaded Ukraine last February. What began as a relatively low-risk but rewarding task became a high-risk endeavor demanding professionalism and patriotism. The teams working in Lyman are part of the Pyrotechnic Works and Humanitarian Demining Department of the government emergency services. Most are highly trained, seasoned veterans, with many years of experience under their belt. Their rotations last 50 days.

Mykhailo Marchuk, a native of Rivne in western Ukraine, has been demining since 2007. Back then, he was primarily tackling leftover mines from World War II. He says the most challenging part of his work now is demining unexploded cluster munitions, anti-tank mines, and small, scatterable anti-personnel minelets. “I never imagined I would do so much demining – that I would be working in an actual war,” he says.

“If the war ended we could do our jobs calmly and easily demine everything,” says his colleague Taras Depanov. “Now we clear an area but a few days later a rocket lands. Then the civilians think we did not do our job properly.”

The level of risk for deminers varies with the seasons and the distance from the front line. The further away you are, the more effective and consistent your work can be, explains Mr. Depanov, whose meticulous character is evident in his tidy gear harness. In the case of Lyman, the sound of artillery duels in the nearby village of Torske serves as a reminder of the war’s proximity.

“You need to have willpower and a strong spirit as well as professional skills and knowledge to do this job,” says Mr. Depanov. “If we are in an anxious state of mind or have a bad feeling, our commanders tell us to stay home.”

The deminers say they are often flagged down by homeowners who want their advice on whether rocket fragments or artillery shells littering their rooftops and gardens pose a threat. Those living in areas that experienced intense fighting, like Lyman, are more sensitive to the risks. But lives are still lost; soldiers and civilians perish in explosions as they drive down roads once controlled by Russians; farmers are killed tilling land peppered with mines; walkers set off booby traps in the forest as they pick mushrooms.

“There are two aspects of vulnerability to this danger: physical and psychological” says Tymur Pistriuha, head of the Ukrainian Deminers Association, a nongovernmental organization. “The most vulnerable people from a mental point of view are children, who, because of their natural interest in the world, now have to live in fear and beware of danger at any time.”

Physically, the most vulnerable are men, he says, because they often ignore or underestimate the danger of touching or moving an undetonated shell. They include men who gather salable scrap metal in areas close to the front line.

“Mines are perfect soldiers”

Demining teams are also hard at work in a forest-fringed stretch of land that falls within the once bucolic, now highly traumatized district of Bucha, outside Kyiv, which Russian troops occupied and then abandoned soon after the war began. This was a front line then, and it is still littered with anti-tank mines. They need over 100 kgs (220 lbs) of pressure to be triggered, but become volatile over the years.

“Mines are perfect soldiers,” says Oleksandr Kotvytskyy, Kyiv regional supervisor for The Halo Trust, an international demining NGO working in several regions of Ukraine. “They can lie in wait for years and then strike.”

The Ukrainian deminers working under Mr. Kotvytskyy’s supervision do so at a steady pace, equipped with protective gear that includes face shields, modern metal detectors, and color-coded stakes to mark their findings. They work 25 meters (82 feet) apart to minimize casualties if something explodes.

The rusting carcass of a car that hit an anti-tank mine hints at danger, and illustrates the need for attention. “For small villages like this, roads are their lifeline to the world,” says Mr. Kotvytskyy.

He calculates that one year of war creates about 10 years of demining work. The organization has identified over 60 minefields in the broader Kyiv region. The need for personnel is high.

For now, committed recruits can be found. Among them is Anna Davydovska, who attended a month of intensive demining training in October 2021 and relocated once it became impossible to live in her native Donetsk region.

“The biggest priority is that we are doing something for our land,” she says, adding that she loves the chance to move about and breathe fresh air, even if her muscles are sore and her hands blistered at the end of the day. Her adult son followed her lead and became a deminer too.

“I know that my family and I are 100% useful to our country,” she says. “That’s the most important thing.”

Oleksandr Naselenko supported the reporting of this article

In Japan, Unification Church scandal stains integrity of ruling party

In Japan, the relationship between LDP lawmakers and the controversial Unification Church has gone from open secret to political crisis, as the ruling party attempts to reassure the public of its integrity.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Takehiko Kambayashi Contributor

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s cozy relationship with the Unification Church was thrust into a harsh spotlight this year after the assassination of former premier Abe Shinzo in July broke a decades-long taboo around discussing the church, which critics call a cult.

Since 1987, lawyers and the National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan have received around 35,000 complaints concerning the church’s “spiritual sales,” in which followers are pressured to buy exorbitantly priced jars and beads to supposedly free themselves from bad ancestral karma. Meanwhile, as followers’ families went bankrupt, LDP lawmakers’ involvement in church activities helped boost the organization’s credibility and party leaders benefitted from Unificationists’ campaign support.

In an effort to contain the crisis – and reverse the party’s plummeting approval ratings – Prime Minister Kishida Fumio has ordered an investigation that could result in the church losing its tax-exempt status.

But the ordeal has already cast doubt on the integrity of the LDP, as well as other institutions that have failed to scrutinize the church’s political influence.

“That the problems had not come to light for decades is a big issue in its own right,” says Kimura Sou, a lawyer in Tokyo, adding, “The government should have offered a helping hand to those in trouble with the church.”

In Japan, Unification Church scandal stains integrity of ruling party

Hashida Tatsuo struggled to hold back tears as he vented pent-up anger at a controversial church he says ruined his family.

His wife became a follower of the South Korea-based Unification Church about 30 years ago, Mr. Hashida explained during a recent meeting with opposition lawmakers in Tokyo. His wife was told there were “evil spirits” in the family’s rice field on the island of Shikoku, which she later sold and donated the money to the church. In total, Mr. Hashida says she gave them about 100 million yen, or $678,000.

“Why did an ordinary family have to do this for the sake of the Unification Church?” asked the farmer.

He and his wife, still an active member of the church, divorced about nine years ago. Their adult son died by suicide in 2020.

Throughout all this, Mr. Hashida approached police, lawyers, and local government officials for help. “But nobody would listen,” he said.

Japanese society is now listening to Mr. Hashida and other victims after the assassination of former premier Abe Shinzo in July broke a decades-long taboo, and exposed the ruling party’s cozy relations with the church, which critics call a cult. Since the shooting, ties between members of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the church have emerged, and approval ratings plummeted, as the public calls into question the integrity of the government.

As Prime Minister Kishida Fumio tries to contain the crisis, even ordering a first-of-its-kind investigation into the church, some voters say the controversy has them reevaluating how they pick their leaders.

“In the next elections, we need to be more careful about who we vote for and what kind of background candidates have,” says Kaneko Mitsuhiro, a small business owner in Tokyo.

A longstanding relationship

The LDP’s ties with the church, known officially as Family Federation for World Peace and Unification, trace back to the 1960s. Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke, Mr. Abe’s grandfather, developed a friendship with Sun Myung Moon, who founded the church in 1954 and shared the Japanese leader’s staunch anti-Communist stance. That relationship helped the organization establish itself in Japan.

While the church has also been active in other countries, Japan is the only nation that sees victims of its “spiritual sales,” in which followers are pressured to buy items like jars and beads at exorbitant prices to supposedly free them from bad ancestral karma, according to the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales. Followers were also told to pay for their ancestors’ war crimes committed during Japan’s colonial rule on the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945, says Yamaguchi Hiroshi, one of the lawyers who leads the network.

From 1987 to 2021, lawyers and the National Consumer Affairs Center of Japan have received nearly 35,000 complaints concerning such sales, according to the network.

As for political ties, church officials argue they have not asked followers to support any specific party, but they are willing to support lawmakers who have an anti-Communist stance.

For some politicians – including Mr. Abe’s younger brother and former Defense Minister Kishi Nobuo, as well as LDP policy chief Hagiuda Koichi, who was Mr. Abe’s right-hand man – that means followers, widely known as “Moonies” though they refer to themselves as “Unificationists,” volunteered to work on election campaigns. According to journalist Suzuki Eito, who has covered the Unification Church for more than a decade, some LDP lawmakers also received monetary donations from Church-affiliated groups.

Meanwhile, LDP lawmakers’ involvement in church activities have helped boost Unificationists’ credibility, Mr. Yamaguchi says. Indeed, his group had repeatedly urged Mr. Abe to refrain from attending events organized by the church and its affiliates, but their pleas were dismissed.

In September 2019, Mr. Abe appeared in a video message aired at a church event, paying his respects to the church’s leadership and followers for their “efforts toward conflict resolution around the world, especially the peaceful unification of the Korean Peninsula.”

From open secret to political crisis

This summer, the church and LDP’s intertwined history was thrust into the spotlight when Yamagami Tetsuya, suspected gunman in the Abe shooting, told police that he resented the former prime minister for his links to the church, which he blamed for destroying his family.

Fukumoto Nobuya, a lawyer for the church, has confirmed Mr. Yamagami’s mother made “excessive donations” amounting to more than 100 million yen.

Soon after, an internal LDP survey showed 179 of its 379 national lawmakers had some connections with the church, for which Mr. Kishida apologized and vowed to sever relations between the party and the church. But public opinion continued to plunge as more interactions between the church and LDP heavyweights, including House Speaker Hosoda Hiroyuki, surfaced.

According to a Jiji Press poll, the approval rating of Mr. Kishida’s cabinet plummeted to the record low of 27% in October from 50% in July. Rising prices without wage growth, and the premier’s decision to hold a state funeral for Mr. Abe in September despite strong public opposition, also contributed to the sharp fall, analysts say.

And the connections keep coming. Economic Revitalization Minister Yamagiwa Daishiro was forced to step down in late October after a 2019 photo emerged of him and Hak Ja Han, the current church president and widow of Mr. Moon, standing side by side. Until the photo surfaced, the minister had evaded the issue, insisting he had “no recollection” of his involvement in the organization’s events.

To calm the waters, Mr. Kishida has taken the highly unusual step of ordering an investigation into the Unification Church. Depending on the outcome, it could be deprived of its tax-exempt status.

Education Minister Nagaoka Keiko announced on Friday that authorities will complete initial questioning by year-end, marking the first time the government has utilized its right to question a religious organization under the Religious Corporations Law. The full probe may take much longer.

Mr. Hashida and ex-followers who want the church to be dissolved view Mr. Kishida’s decision as a “step forward,” though some critics have called it a “stall tactic.”

Hard look at Japan’s institutions

The crisis has not only cast doubt on the integrity of the LDP, but also other institutions that have failed to scrutinize the church’s political influence.

Some argue that Japan’s major news organizations have largely failed to report on the authorities’ long-standing ties with the church.

“The LDP should no longer exist as a political party because it utilized the Unification Church for its election campaigns,” says Asano Kenichi, a former journalism professor at Doshisha University in Kyoto, adding that journalists must continue investigating the LDP and Unification Church. Through their reporting, he hopes the media can help improve government integrity, as well as establish a higher standard of journalism that “the public can trust, whose main duty is to serve as a watchdog on power.”

Others attribute this crisis in part to a lack of clarity about the role religion should play in Japanese law and society.

A group of 25 religion scholars from across the country issued a statement saying Japan “needs to develop a clear understanding of the whole concept of religion and the relationship between religion and politics,” and calling on the government to “provide a prompt and appropriate response through a transparent process to prevent more victims.”

That’s one area where there now seems to be broad agreement – that Japan’s government has been failing the people who’ve watched their families deteriorate while pumping money into the Unification Church. Since establishing a victim hotline on Sept. 5, the government’s received more than 3,800 calls, mostly from ex-Unificationists and concerned relatives.

While the forward momentum is inspiring hope, many are left wondering why it took so long.

“That the problems had not come to light for decades is a big issue in its own right,” says Kimura Sou, a lawyer in Tokyo. “Police and government officials had duly hesitated to deal with it because they thought it was a religious matter. I believe that attitude was fostered by the fact that lawmakers received support from the church and that some lawmakers even … seemed to give endorsement to the organization.”

“The government should have offered a helping hand to those in trouble with the church,” he adds.

Points of Progress

Lifesavers: From demining Angola to calming traffic in Japan

Our progress roundup looks at big problems with multifaceted solutions that also yield multiple positive effects. In Angola, teams of women are removing land mines to make places safe again. And in Japan, everything from better train service to tiny cars has reduced traffic fatalities.

Lifesavers: From demining Angola to calming traffic in Japan

1. Canada

Chopsticks are proving that a circular business can be created from single-use products. The idea for a sustainable home furnishings company came to engineer Felix Böck after he had just given a seminar on sustainability in Vancouver, British Columbia, and a waiter threw away his chopsticks at a sushi restaurant. “Suddenly, I understood that I had to show people how circular economy works instead of just talking about it,” Mr. Böck said. He began his startup, called ChopValue, creating coasters and cutting boards from disposed chopsticks, which are usually made of bamboo. Since then, the company has grown to a staff of 35 people; the team collects 350,000 chopsticks from restaurants in Vancouver each week – 70 million in total across its operations so far.

The chopsticks are treated with high heat and pressure at franchise microfactory locations from Liverpool to Bali to create products like shelves, desks, wall panels, and stairs. On its own, ChopValue will not make a dent in the global trash problem. But if other businesses follow suit, the effects could ripple. Mr. Böck’s hope is that “every city adopts the concept of urban recycling instead of just transporting their trash out of town and say[ing], great, now we’re done. ... Because trash is never gone.”

Source: Reasons to be Cheerful

2. United States

Nicole Mann became the first Native American woman in outer space. NASA’s SpaceX Crew-5 mission launched Oct. 5 from Florida’s Kennedy Space Center. With Colonel Mann as commander, the crew will spend five months on the International Space Station. Colonel Mann is a member of the Wailacki, one of the Round Valley Indian Tribes. She has served over two decades in the U.S. Marine Corps, which includes 47 combat missions in Afghanistan and Iraq. She joined NASA in 2013.

Despite Colonel Mann’s success, structural barriers persist for young Indigenous Americans. As of last year, 24% of Native American 18- to 24-year-olds were enrolled in college, as compared with 41% of the general population. Colonel Mann said she hopes her journey leaves a mark on young observers from disadvantaged backgrounds: “[I hope it] will inspire young Native American children to follow their dreams and realize that some of those barriers that are there or used to be there are being broken down.” Colonel Mann is also the first female commander of a SpaceX mission.

Sources: Smithsonian, BBC, Postsecondary National Policy Institute

3. Angola

Angolan women are demining their country, breaking down stereotypes while earning a stable living. Three decades of civil conflict between 1975 and 2002 left some 73 million square meters (18,000 acres) of Angola contaminated by land mines, which continue to claim lives and stifle agriculture and development. While the job of demining was once assumed too dangerous and demanding for women, the HALO Trust launched an initiative in 2017 to recruit 100 female deminers in Angola. Today, close to 400 women have answered the call, with several dozen more in training.

The work of detecting and deactivating mines is challenging, with days starting at 4:50 a.m. and visits home just once a month. But the steady income of $350 goes a long way in a country with an average monthly income of around $35, according to 2018-19 data. So far only a fraction of the contaminated land has been cleared, though deminers are making progress. The province of Huambo, once one of the most heavily mined areas of the country, was fully cleared of minefields in 2021. “Every time we destroy a mine I feel proud,” says deminer Cecilia Manuel. “When you take away the mines, you make the people free.”

Sources: NPR, Mines Advisory Group

4. Finland

The world’s first “sand battery,” capable of storing green power for months at a time, is up and running in Finland. One obstacle to year-round renewable power is the difficulty of capturing and storing energy when intermittent sources like wind or solar energy are unavailable. Finnish engineers at Polar Night Energy have employed a solution in a simple material: low-grade sand.

The battery they devised involves a tank measuring 13 by 23 feet, filled with 100 metric tons of sand, for 100 kW heating power and 8 MWh capacity. Solar or wind energy is converted into hot air, which keeps the sand at a temperature of 500 degrees Celsius (932 degrees Fahrenheit). For the town of Kankaanpää, that heat warms water that is then pumped to local buildings via a district heating network, serving some 10,000 people.

Unlike expensive lithium batteries, which leave a considerable physical footprint, the sand battery has a minimal environmental footprint. Developers say the design won’t be affected by sand shortages in the glass and concrete industries because the technology uses low-grade sand or sandlike materials.

Sources: Dezeen, BBC

5. Japan

The number of annual traffic fatalities in Japan is 16% of what it was half a century ago. Since their peak in 1970, when 16,765 people died in collisions, deaths caused by road accidents have declined steadily in Japan. The 2021 total was the lowest on record, lower even than when data collection began in 1949 – a per capita rate that is less than a fifth of the rate in the United States.

The late 1960s became known in Japan as the “traffic war,” prompting a government response that spanned regulations, law enforcement, education, and vehicle safety standards. Since then, improvements in rail travel and deterrents to driving such as prohibitions on street parking have shifted consumer preference away from cars. The average Japanese drives a third as much as the average American. Meanwhile, microcars, whose compact designs reduce blind spots and generate less force in collisions, make up a third of new cars sold in Japan.

Sources: Bloomberg, The Asahi Shimbun, Journal of the International Association of Traffic and Safety Sciences

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Mexico’s people power

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Over the past four years, proponents of democracy have grown increasingly alarmed as Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has gained outsize influence over Congress, the judiciary, and the military. But on Sunday, the people drew a red line. In some 50 cities across the country, tens of thousands poured into the streets in coordinated protests over the president’s proposal to replace the National Electoral Institute.

The marches were the largest single public expression of dissatisfaction that Mr. López Obrador has faced since he took office, for good reason. The INE, as it is known by its Spanish acronym, is one of the most trusted government institutions in Mexico and the guardian of the public’s desire for self-government. Critics worry that the president’s reforms would render the institute a tool of the ruling party and jeopardize the country’s fragile renewal of democracy since 2000 after 71 years of one-party rule.

In Mexico, the people’s defense of a trustworthy democratic institution offers a rebuke to Mr. López Obrador’s tilt toward one-party rule dominated by a singular personality.

Mexico’s people power

Over the past four years, proponents of democracy have grown increasingly alarmed as Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has gained outsize influence over Congress, the judiciary, and the military. But on Sunday, the people drew a red line. In some 50 cities across Mexico, tens of thousands poured into the streets in coordinated protests over the president’s proposal to replace the National Electoral Institute.

The marches were the largest single public expression of dissatisfaction that Mr. López Obrador has faced since he took office, for good reason. The INE, as it is known by its Spanish acronym, is one of the most trusted government institutions in Mexico and the guardian of the public’s desire for self-government. Critics worry that the president’s reforms would render the institute a tool of the ruling party and jeopardize the country’s fragile renewal of democracy since 2000 after 71 years of one-party rule. “I defend the INE,” protesters chanted. “The INE defends my voice.”

“Today, we reaffirm our deep commitment to democracy,” José Woldenberg, the institute’s former president, told marchers in Mexico City. “We defend an electoral system that ... allows the coexistence of diversity and the replacement of governments through peaceful and participatory means.”

The protests are a response to a set of government reforms proposed by Mr. López Obrador, a populist and one of the first in a wave of leftist leaders that has spread across Latin America in recent years. Those measures, first floated in April and now being debated in Congress, would cut 200 (out of 500) legislative seats, eliminate public funding and media to political parties, and replace the INE with a new body composed of candidates named by the president, Congress, and Supreme Court.

The proposals have almost no chance of passing since the ruling party lacks the votes to enact constitutional amendments. But critics say they reflect an ongoing effort by Mr. López Obrador to consolidate power in the ruling party and “gut the institutions that have guaranteed democratic practices for a generation,” as Pamela K. Starr, a professor at the University of Southern California, told The Dialogue. The president, critics note, still harbors resentment against election officials from his failed bids in 2006 and 2012.

Mr. López Obrador reiterated his claims of widespread electoral fraud yesterday, dismissing the protests without explanation as “a false flag” in favor of corruption, racism, classism, and discrimination.

Watchdogs of democratic wellness use a range of indicators such as free speech and political competition to measure the openness of societies. If those factors focus too much scrutiny on what governments are doing, however, they may miss underlying currents of civic strength – particularly in places where populist or autocratic regimes seem to be flourishing. In Mexico, the people’s defense of a trustworthy democratic institution offers a rebuke to Mr. López Obrador’s tilt toward one-party rule dominated by a singular personality.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Challenge age-related limitations

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Pamela McKnight

Turning to God, rather than our bodies, to learn about our true state of being opens the door to healing – as a woman experienced when faced with chronic difficulties with her knee.

Challenge age-related limitations

I am past what is commonly called retirement age, and several years ago I noticed I was having mental conversations with myself that began something like this: “I wonder how much longer I will be able to hike these steep trails.” Or, “I hope I will be able to continue taking care of my yard.”

Christian Science teaches that we can challenge the limiting notion of an expected decline of strength and vigor. So I turned to the Bible and to the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, to gain some spiritual insights on this.

The Bible is full of examples of people overcoming limiting claims of old age. Abraham and Sarah conceived and bore Isaac in very advanced years. Moses was 80 when he confronted Pharaoh in order to free the children of Israel. And the writer of Job encourages an expectancy of health, not decay: “Thine age shall be clearer than the noonday; thou shalt shine forth, thou shalt be as the morning” (11:17).

Science and Health offers this encouraging insight: “God expresses in man the infinite idea forever developing itself, broadening and rising higher and higher from a boundless basis” (p. 258). “Forever developing,” “broadening,” “rising higher and higher.” This is our continuing identity! Not mortals subject to inevitable decay, but God’s spiritual offspring, reflecting His forever-unfolding goodness.

As I prayed with these and other ideas, the negative mental conversations dramatically decreased.

A few months later, I began to have trouble with my right knee. I had not injured myself, but it was becoming painful to walk or to bend the knee. I could not sit cross-legged on the sofa, which is my preferred position when relaxing. It seemed to be a condition associated with old age.

The insights I’d been gaining from my prayers prior to this situation gave me confidence to replace thoughts of pain and limited mobility with spiritual facts about our true nature as spiritual, not material. I was able to continue with normal activities, including going for walks in the hills behind my house – not by willing my way through them, but through prayer, rejecting the thought that anything could interfere with the freedom and strength we reflect as God’s spiritual ideas.

One morning about a year later, as I was walking up one of the steeper hills, I noticed that my knee was less painful. I remember thinking, “Well, my prayers must finally be working because my knee is feeling better!” Then it was as if I heard a voice saying, “Pam, are you really going to let your knee tell you if your prayers are working?”

The question stopped me in my tracks. Was I letting my knee tell me how I was, or was I turning to God to learn about the state of my well-being?

Science and Health says, “To be immortal, we must forsake the mortal sense of things, turn from the lie of false belief to Truth, and gather the facts of being from the divine Mind” (p. 370). Truth and Mind are Bible-based synonyms for God, and right then on that hill, I determined that I was going to gather the facts about my being only from God. My very brief mental conversation went like this: “No, knee, I am not well because you tell me I am well. I am well because God has made me well – now and always! And I know it!”

That was the very last time I even thought about my knee. I realized it had stopped being a problem perhaps a week or two later, when I found myself sitting cross-legged on the sofa. This healing occurred over two years ago, and has remained permanent. I have taken many strenuous hikes in the mountains and done many strenuous chores outside since that time, without a speck of discomfort.

We have a divine right to challenge thoughts based on mortal, human beliefs instead of the spiritual facts of being. It’s from God, not matter, that we discern the state of our true being as spiritual and whole – a healing perspective. We can take to heart this instruction in Science and Health: “Mortals must look beyond fading, finite forms, if they would gain the true sense of things. Where shall the gaze rest but in the unsearchable realm of Mind?” (p. 264).

A message of love

Eight billion

A look ahead

You’ve reached the end of today’s story package. Tomorrow’s stories include a look at how the movie “Black Panther: Wakanda Forever” honors the beloved actor Chadwick Boseman.