- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As assisted dying broadens, countries wrestle with new ethical lines

- Once influential, Russian soldiers’ mothers speak softly amid Ukraine war

- Mexico arrests son of ‘El Chapo’: Why don’t citizens feel safer?

- Robot pals and AI tools: What’s ahead for tech in the classroom?

- Power unlocked: Debt funds wildlife, refugee brings solar to camp

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Biden, Trump, and questions of classified-doc equivalence

What’s up with all these classified docs?

First it was the FBI search of former President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort, which turned up dozens of papers with classified markings at multiple locations. Now the Justice Department has launched a review of classified documents found at the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy & Global Engagement, a Washington think tank established by now-President Joe Biden following his vice presidency.

The White House confirmed the Penn Biden Center inquiry and said it was cooperating. Officials said the documents, discovered last November, were quickly returned to the National Archives and Records Administration.

Mr. Trump and his allies have tried to establish equivalence between his and Mr. Biden’s document problems. If voters judge them the same, it could be politically more difficult for the Justice Department to prosecute Mr. Trump for his retention of presidential records.

“When is the FBI going to raid the many homes of Joe Biden, perhaps even the White House?” Mr. Trump said on his social media platform.

We don’t know everything yet about the Biden documents. Retaining classified information without authorization is a serious matter. But some experts said the two situations were far from comparable.

First is sheer numbers. Mr. Trump had more than 300 classified documents at Mar-a-Lago, plus boxes of unclassified records.

Second is lack of cooperation. Mr. Trump stonewalled requests for documents and then misled the government about papers still in his possession.

Third is possible obstruction. There are indications that boxes of documents were moved at Mar-a-Lago prior to visits from archive officials. A Trump lawyer signed an affidavit attesting all docs had been turned over, when they hadn’t.

“If upon learning that you have docs, you return them, there is no crime. That is not what Trump did,” tweeted former Justice prosecutor Andrew Weissmann.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

As assisted dying broadens, countries wrestle with new ethical lines

Colombia and Canada sit at the forefront of a global shift of ideas around assisted dying. While some consider the practice to be the ultimate act of compassion, others worry it’s gone too far.

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Dominique Soguel Special correspondent

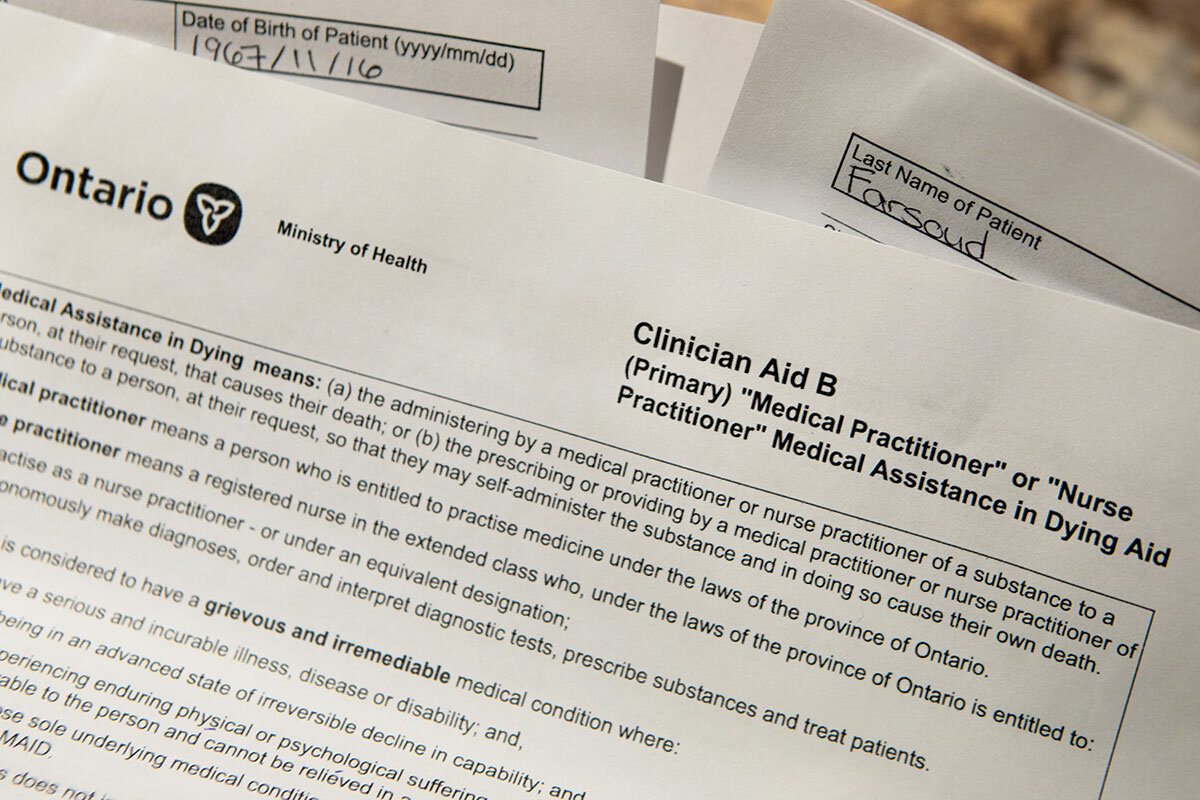

Amir Farsoud has had chronic pain for years, but it was only when he found out he might become homeless that he started moving forward with the paperwork necessary for Canada’s medically assisted dying program – helping spark conversation among Canadians about how the country treats people not only in death, but in life.

The debate has intensified as Canada has moved to open its assisted death program to patients with mental health disorders – who still meet all other criteria – as the sole justifying condition.

Canada isn’t alone. As countries around the world continue to adopt laws or expand what they deem acceptable reasons for medically assisted death and suicide, they are reshaping the debate in new ways. No longer is this merely a question of how to address older people with a terminal diagnosis. What are the ethics of the state sanctioning suicide for a young person struggling with depression? What role should nations play in determining when death might be preferable to pain? What, in other words, does a caring society truly look like?

While the debate has roiled Canada, supporters see assisted dying as something that’s bigger than death – about quality of life as a whole.

“Assisted dying is less about death than it is about how we want to live,” says Canadian doctor Stefanie Green.

As assisted dying broadens, countries wrestle with new ethical lines

Federico Redondo Sepúlveda and his mother, Martha Sepúlveda, were inseparable.

So when she fought for her right to an assisted death – to relieve her suffering from a progressive neurological disorder that she was diagnosed with in 2018 – he was shaken. She’d only heard that Colombia allowed euthanasia because Mr. Redondo happened to share with her the topic of his law school class that day.

As she pushed for her own access – after the Constitutional Court of Colombia extended the right to those like her without an immediate terminal prognosis in 2021 – he would avoid the subject, leaving the table to make a call or take out the trash. “It’s always been just me and my mom,” says Mr. Redondo, an only child. “I’d say things like, ‘Ma, you’re just going to leave me on my own? You have so many things that are worth living for!’”

Yet over time, as her illness progressed and a new reality dawned, he came to reframe discomfort from her perspective, from a woman whose core value she had long imparted to her son: “to live was to decide.” On Jan. 8, 2022, she became one of the country’s first citizens to die in a case with a nonterminal prognosis, her son at her side.

A month earlier, in Toronto, another mother and son were facing a voluntary death, but this time it was the son who wanted to die.

Sharon Danley says her son, Matthew Main, was diagnosed at birth with multiple conditions, underwent dozens of surgeries as a child, and complained of chronic physical pain into adulthood. He was eligible for Canada’s medical assistance in dying, known as MAiD, after the law was amended in 2021 to include those whose deaths aren’t “reasonably foreseeable.”

Her son had told her in 2020 about his intention to take advantage of MAiD, Ms. Danley says. She was against it from the start. “When someone tells you that they’re going to be euthanized, it’s like it brings you to your knees. You can’t fathom it, and that waiting for the day to happen is excruciating.”

Their relationship, already contentious, deteriorated so much that, by the time his appointment to die arrived, he, along with family and friends, had shut her out completely. When the time came on Dec. 12, 2021, Ms. Danley was not at her son’s side. She was at her apartment blocks away in downtown Toronto.

Colombia and Canada sit at the forefront of the Americas – and indeed the globe – in allowing assistance in dying. While some consider the practice to be the ultimate act of compassion, others worry it’s gone too far.

Both countries are among a handful that allow it and an increasing list of those considering it – and expanding eligibility. They join Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg in allowing euthanasia for those who are not terminally ill. Canada is in the middle of heated debate as it is expected to move further in March when MAiD could become available to those with mental health disorders as the sole justifying condition.

The notion of assistance in dying as an act of mercy is centuries old. But as it has been inscribed in state law in the last generation it has become part of the culture wars in the West, pitting right against left and the secular against nonsecular. It goes much deeper than a political wedge issue though.

Does Mercy Have Limits?

The notion of assistance in dying as an act of mercy is ancient. Now it has become part of a global debate that’s taking a variety of forms, and that ultimately is about what a caring society truly looks like. How a team of Monitor writers parsed that, with care and compassion. Hosted by Samantha Laine Perfas.

As countries continue to adopt laws or expand what they deem acceptable, they are reshaping the debate in new ways. No longer is this merely a question of how to address older people with a terminal diagnosis. What are the ethics of the state sanctioning suicide for a young person struggling with depression? What role should nations play in determining when death is preferable to pain? In other words, the debate raises questions about what constitutes discrimination and equity of rights, what makes a person vulnerable, and ultimately what a caring society truly looks like.

Euthanasia – meaning literally the good death – has roots in ancient Greece, where hemlock was used to quicken a patient’s death. In modern times, laws around assisted dying, including euthanasia, and assisted suicide first took shape in Europe.

Today, eligibility for euthanasia, the practice of a medical practitioner ending a patient’s life at his or her explicit request, is most expansive in the so-called Benelux countries; it has been legal for two decades in Belgium and the Netherlands, and since 2009 in Luxembourg. Euthanasia also became legal in Spain in 2021 and would be in Portugal if not for two presidential vetoes. Laws on assisted dying are being vigorously debated in France and Scotland.

Assisted suicide, whereby the patient wishing to die administers the fatal dose, became legal in Austria last year and has been legal in Switzerland since 1942, although not so for euthanasia. A strong distinction between the two is also made in Germany, which is still reeling from the history of Nazi-era mass murders by involuntary euthanasia of people with disabilities.

Worldwide at least 25 jurisdictions now allow some form of assistance in dying – including 10 countries, 11 U.S. states, and four Australian ones. But the vast majority of the world still shuns active euthanasia. It’s not legal anywhere in Asia, Africa, or the Middle East.

In Latin America, the conversation is starting to shift, as societies move away from both the dominance of the Roman Catholic Church and the authority of doctors over patients’ rights. When Colombia legalized euthanasia for terminally ill patients in 1997 in a court-driven move, it was a regional outlier. It wasn’t until 2015 that the first procedure was approved, after a court ruling ordered the Ministry of Health and Social Protection to regulate it.

Between 2015 and October 2022, more than 329 patients in Colombia died by euthanasia. In more recent years, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay have tested legislation to make it legal.

For Shanthi Van Zeebroeck, a researcher in interdisciplinary law and biomedical sciences who has conducted qualitative research on the euthanasia practices in Belgium, it is no surprise that the Benelux countries, which boast high quality of life, pioneered euthanasia. She sees culture as a key reason for the split between the developing world and wealthy nations on the subject.

“People think you oppose or support it based on [religious commands], but it has nothing to do with it. It’s based on the way you are raised,” she says.

In many Western countries, citizens are accustomed to freedom, autonomy, and convenience. “As soon as your quality of life is compromised, [many ask] then what is the point of living?”

But in developing countries, she says, most are raised to accept sacrifices. That in turn shapes notions of what constitutes dignity and compassion. If a person is nearing death with a health issue, the expectation is they should suffer through it.

Canada has quickly become one of the world’s most permissive jurisdictions on assisted dying.

Assisted dying in Canada is rooted in a 2015 Supreme Court decision that reasoned that to deny the possibility of an assisted death to someone whose illness is “grievous and irremediable” and whose suffering is “intolerable” would deny those citizens protections under Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A 2021 Ipsos poll, found that 87% of Canadians support that decision.

The MAiD legal framework was created to regulate the ruling, though the law initially was more restrictive than the court’s criteria because MAiD as first written required a “reasonably foreseeable natural death.” A 2019 court ruling in Quebec deemed the “reasonably foreseeable” criteria unconstitutional however, and so the federal government removed that requirement in March 2021 with Bill C-7, opening up the procedure to patients like Mr. Main, even though he wasn’t imminently dying.

Bill C-7 excludes those whose mental health disorder was the sole underlying illness – an exclusion that was set to expire in March 2023. But the federal government announced in December it will seek to delay the expansion.

In 2021, there were 10,064 MAiD provisions in Canada according to government figures, bringing the total number of medically assisted deaths since 2016 to 31,664 – the vast majority older Canadians with terminal diagnoses. A 2020 study found that MAiD recipients in Ontario tended to be wealthier, less likely to be in institutional care, and more likely to be married than the average Ontario decedent.

Dr. Stefanie Green calls Canada a global leader today because it frames MAiD as a rights-based issue, guaranteeing the possibility of care for all eligible Canadians.

“This is about wanting to help someone who is in a dire situation,” says Dr. Green, who is the president of the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers and author of the book “This Is Assisted Dying.” While each case is different, she says, the one constant is the relief she sees when her patients learn they are eligible. “They feel emboldened, empowered ... the power of that possibility is something I am struck with over and over again,” she says. Sometimes that’s enough to make them forgo the provision.

In comparison, in the United States assisted suicide has been enacted by popular vote or legislatures in various states. That makes assisted dying vulnerable to “societal mood,” she says. And euthanasia remains illegal across the U.S. – putting assisted dying out of reach for those unable to self-administer treatment.

Dr. Green was a family practitioner on Vancouver Island with a strong focus on maternity and newborn care for over 20 years, delivering babies whose photos still decorate her office. But she sees parallels in her end-of-life work. She was one of the first clinicians in Canada to provide MAiD, in 2016, and to date, has helped around 300 patients die.

“Assisted dying is less about death than it is about how we want to live,” she says.

But where she sees world leadership, other doctors worry Canada is moving too fast and too far. Dr. Sonu Gaind, incoming chief of psychiatry at Sunnybrook Health Centre in Toronto, calls Canada a “cautionary tale for the world.”

Dr. Gaind, the former president of the Canadian Psychiatric Association, says he is not a conscientious objector to MAiD. He is the physician chair of his current hospital’s MAiD team assessing eligibility. But he announced he would be stepping down when Canada expands eligibility to psychiatric patients.

At the heart of his concern is whether mental illness can accurately or scientifically be assessed to be “irremediable,” and whether offering a death service to those with suicidal ideation is ever a compassionate way forward. “We will be providing MAiD to people who are in their darkest periods of despair, who can’t see a reason to live,” he says. “We will be providing death under false pretenses, and I can’t participate.”

In countries where patients are already able to access assisted dying for mental health reasons alone, such cases remain a small fraction of all assisted deaths. Of 7,666 assisted deaths in the Netherlands in 2021, for example, the vast majority were people with terminal diagnoses, and only 115 cases involved those diagnosed with severe psychiatric disorders.

Still, Dr. Gaind points to a 2016 study of euthanasia and assisted suicide of patients with psychiatric disorders in the Netherlands from 2011 to 2014. Although the sample size is tiny with just 66 cases, that study indicated a gender disparity: 70% of recipients were women.

Cases for minors and psychiatric patients, where the judgment of the patient is called into question, have sparked the fiercest ethical debates – and legal scrutiny. In October a Belgian woman in her 20s was offered assisted dying due to a mental crisis after having lived through a terrorist attack at the international airport in Brussels in 2016. The Netherlands’ first criminal court cases over euthanasia concerned women suffering from mental disorders, though the cases did not result in convictions of the doctors involved.

For the past two years in Canada, a parliamentary committee has been exploring a number of contentious issues related to assisted dying. A separate expert panel has reviewed the issue of MAiD and mental health with respect to the safeguards that are in place (including that no patient can seek death in a crisis). The government’s last-minute effort to delay it has been called disappointing and discriminatory by right-to-die advocates.

While Dr. Green has already assisted people with mental health disorders with concurrent physical illness, she says in some ways Canada is entering new territory – she feels as she did in 2016, knowing she will be searching anew for her own comfort level and balance.

“It is contentious, and it should be contentious,” she says. “But nobody does this lightly; nobody takes this as a tick, tick, tick, tick, tick box. We do it cautiously, carefully, and compassionately.”

For Dr. Gaind, however, no safeguards are enough when the country offers assisted dying to those not dying. The very name MAiD today, he says, has become a misnomer, and could attract the most marginalized in the name of autonomy.

“We haven’t had a slippery slope in Canada. There’s been no slope at all, there’s been a cliff, and we have fallen over that cliff,” he says. “This is what I call false autonomy and false compassion.”

Part of the challenge for Canada as it tests the tolerance to assisted dying is that it is dealing with patients who do not look like what society might expect: older or frail.

When Canada introduced Bill C-7 for those whose deaths are not “reasonably foreseeable,” the new legislation received harsh rebuke from many advocates of disabled people. Three United Nations experts, including the special rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, condemned the move for creating or reinforcing an assumption that “it is better to be dead than to live with a disability.”

And in the past year, as media outlets have highlighted people who say they are seeking MAiD because they can’t live on their disability checks, many have conflated Canada’s safety net and its assisted dying laws. British magazine The Spectator asked over the summer: “Why is Canada euthanizing the poor?”

Amir Farsoud, who was born in Iran but left with his family amid the Iranian Revolution and eventually landed in Toronto, answers plainly that he’d rather be dead than homeless.

Mr. Farsoud has chronic pain from a back injury and a series of other medical issues that he says have gotten progressively intolerable. But he only started to seek the first of two required signatures from a clinician to die on Oct. 4, after receiving a notice from his landlord in St. Catharines, Ontario, that he was going to sell the building where Mr. Farsoud currently resides. With a disability check that hardly matches housing inflation across Canada, Mr. Farsoud says he refused to die on the streets.

Mr. Farsoud says since MAiD expanded he has known – and still knows – that he will seek it one day. When he received the first approval, he felt “a mixture of fear – and relief,” he says. “The relief was that at least I could make that choice, I could at least have the control that I had been denied in life.”

But he had to wait 90 days for a second signature, as required by Canadian law when death isn’t “reasonably foreseeable” – a waiting period that Mr. Farsoud fully supports. In that time, the local news ran his story. It generated an outpouring of sympathy, including from an anonymous woman who launched a GoFundMe page that has since raised tens of thousands of dollars.

That was enough to make him forgo pursuing the second signature – for now. “What changed really is hope,” he says.

When Alex Schadenberg, executive director of the Euthanasia Prevention Coalition, hears cases like this, it’s not the Canada he recognizes. “We talk about this progressive, caring society that we live in in Canada where everyone has equality,” he says. But he says in reality it can be quicker to seek MAiD than access proper psychiatric care or find affordable housing. “I just don’t see how this can lead to what we see as a caring society.”

But right-to-die advocates say that those who have been against MAiD all along on moral or religious grounds have sensed an opportunity to sow doubt while changes are afoot and society is jittery.

“I think it’s important that this has brought a lot of attention to the fact that there are not enough social supports or disability support,” says Helen Long, the president of Dying With Dignity Canada. “But you can’t get assisted dying because you don’t have social supports. You can get assisted dying because you meet the entire eligibility criteria.”

Mr. Farsoud says the outpouring of support for his individual case has shown him true compassion. But he bristles at the hypocrisy he sees among those caring so fervently about the sanctity of life but not a person’s life.

“Society has decreed that we’re not human enough; they don’t wish to care about how we live,” he says. “But when you get to the point where you choose that you’re going to die, it becomes, am I going to die well or poorly? And when somebody allows you to pick the well over the poorly between those two choices, if that’s not an act of compassion, I don’t know what is.”

Compassion is the last word that comes to mind when Ms. Danley considers her last year. She does hold some views rooted in conspiracy theories including that euthanasia is part of a larger eugenics movement and cost-savings plan by the government. Still, her son is gone and she says she felt abandoned by a government and medical community that took him away but did nothing to support a mother left behind. “Nobody called to say, how are you doing? Would you like to partake in a program? It doesn’t come with any grief counseling.”

Until the end, she says she really didn’t think it was going to happen. Her son had a history of suicidal ideation, she says. She was used to his highs and lows. Recently he had redecorated his downtown Toronto apartment, she says, and weeks prior to his date he asked her for money to go to New York City – both signs to her that he was doing well.

Throughout that year, she told him if he changed his mind, she was there to talk. But that never came – and she’s been left without closure, and with a rift in her family. “This is the fallout that nobody’s talking about.”

In Canada, support groups have arisen to help families navigate the process. Signy Novak, a nursing educator in Vancouver, launched the MAiD Family Support Society, formerly known as Bridge 4 You, in April 2021 after her father received MAiD and she realized there were few resources for families to ask the simple – or difficult – questions.

Today, her nonprofit counts 30 volunteers across Canada who have guided about 150 families in the past year. Most of them support their loved one’s decision, but sometimes one family member won’t on religious or moral grounds. Some have given little thought to MAiD previously and have to come to terms with their own ethics. Others simply aren’t ready to let go.

“Families are carrying all this stress leading up to the death, and if someone goes through with it but a few family members don’t agree, that grief understandably becomes more complex,” she says.

In Colombia, Ms. Sepúlveda wasn’t supported by her mother. And then her case became a lightning rod within Colombian society – with the Catholic Church speaking out about it and the public debating whether she was too happy to die.

The court-driven right in Colombia, like is the case in Canada, is rooted in human rights. “This isn’t about providing an option to end one’s life, it’s much bigger than that,” says Dr. Julieta Moreno Molina, a bioethicist who has served on the Health Ministry’s committee on assisted dying for the past six years. “In 1997 [the court] said that to die with dignity was part of living with dignity.”

But a true understanding of that case is lost amid polarization, she says.

“When the topic comes up in the media because of a new resolution or because there’s a case like [Ms. Sepúlveda’s], you find a very divided, uninformed society taking on two opposing positions: Either the patient is in charge of their own life and their rights, or the patient isn’t in charge of their own life and their rights,” Dr. Moreno says.

Ms. Sepúlveda was featured in various news coverage for what would have been the first case of a Colombian dying under the 2021 court ruling. In one broadcast, she and her son were filmed at a restaurant, smiling. Society began to debate: Should someone so content be choosing death?

But they misunderstood the smile, says her son, Mr. Redondo. It was one of relief: the very kind Mr. Farsoud articulates. “The ideal is that no one will ever have to make such an extreme decision,” Mr. Redondo says. But not everyone has that privilege.

Nearly a year later, he travels across Colombia for work, practicing law and building his life as a young adult. But sometimes he will still pick up the phone and start dialing his mother’s number before he remembers.

“I wouldn’t say I’m happy. Or comfortable with her being gone,” he says. “Because life was so much easier for me with her in it. But at least I feel calm.”

Sara Miller Llana reported from Toronto, Whitney Eulich from Mexico City, and Dominique Soguel from Basel, Switzerland.

Once influential, Russian soldiers’ mothers speak softly amid Ukraine war

After decades of apathy, Russian officials seem to recognize the military needs to communicate better with families of missing and injured soldiers. But will that mean more honesty or obfuscation?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Of all the ways that citizens interface with their state, there is no relationship so fraught as war service. Most observers say Russia’s record in past wars of treating conscripted troops humanely and keeping families informed has been abysmal.

The chasm between military officials and soldiers’ families persists amid the war in Ukraine. But now there is some evidence that the Russian government has realized that it needs to improve its messaging – though it is unclear whether it intends to do so primarily by outreach or suppression of critical voices.

Russia’s Defense Ministry has established a hotline where families can inquire about a loved one serving in the war zone. Rules for how to claim the remains of a deceased soldier and obtain compensation have also been publicly spelled out.

A New Year’s Eve Ukrainian missile strike on barracks near Donetsk that killed scores of newly mobilized Russian troops provided a stark test of the system. It was quickly admitted by the Defense Ministry, which assured the public that all bereaved families have been informed and will be compensated. But it remains unclear how well the system worked. For example, none of the three hotline numbers publicized by the Defense Ministry seems to be functioning.

Once influential, Russian soldiers’ mothers speak softly amid Ukraine war

In late March, Russia military authorities told Irina Chistyakova that her son, a conscripted soldier, had gone missing amid the war in Ukraine, and was probably dead. She refused to accept that.

Following the example of many brave soldiers’ mothers during Russia’s wars in Chechnya, she headed down to the battlefields determined to find him. And she did.

“I traveled 25,000 kilometers [15,500 miles], in Donbas, Mariupol, Crimea. I was bombed. I visited so many morgues. No one can understand what war is until you’ve seen it yourself,” she told Russian journalists Anton Rubin and Dasha Litvishko in interviews published on their YouTube channel, Razvorot (“Reversal”).

Like many others contacted by the Monitor for this story, Ms. Chistyakova was warned that foreign journalists will distort anything she says and does not want to be quoted directly by an American newspaper. But she has detailed her experiences to Razvorot, including a few scathing criticisms of Russia’s Defense Ministry. “I was doing the work of the Defense Ministry myself. It seems that I am the only person who needs my son. And I found out where he is. He is a prisoner of war in Ukraine.”

Of all the ways that citizens interface with their state, there is no relationship so fraught as war service, particularly when the troops have been conscripted. Most observers say Russia’s record in past wars of treating conscripts humanely and keeping families informed, especially of the worst news, has been abysmal. The impenetrable military bureaucracy and official indifference during the Soviet Union’s war in Afghanistan prompted the rise of the Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers, which organized women like Ms. Chistyakova into a social force that the Kremlin couldn’t ignore.

The chasm between military officials and soldiers’ families persists amid the war in Ukraine. But now there is some evidence that the Russian government has realized that it needs to improve its messaging – though it is unclear whether it intends to do so primarily by positive outreach, suppression of critical voices, or a combination thereof.

“Making mistakes and then correcting them”

After their establishment during the war in Afghanistan, Russia’s various Committees of Soldiers’ Mothers became some of the most powerful civil society organizations Russia has ever seen. Their anti-war stance, and the strong political influence they generated, arguably played a big role in ending both that war and the first Chechnya conflict on terms unfavorable to Moscow.

By the time of the second Chechnya war, in the early 2000s, the Russian state, now headed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, proved far more adept at controlling the media, suppressing public protests, and also at winning the war.

The present conflict in Ukraine presents a far greater challenge, and the Kremlin has clearly given a lot of thought to ways of managing its potentially explosive relationship with the families of service members. Mr. Putin’s well-publicized meeting with a selected group of soldiers’ mothers on Nov. 25 was a televised attempt to get ahead of the issue, and it featured explicit promises from Mr. Putin that the mistakes of the past would not be repeated, families would be kept informed, injustices corrected, and in the event of injury or death, compensation provided.

“I want you to know that we share this pain with you,” he said. “And, of course, we will do our best, so that you do not feel forgotten, so that you feel the support.”

However, Ms. Chistyakova, whose social media posts had generated so much pressure for such a meeting, did not get an invite.

Though it’s hard to judge effectiveness, Russia’s Defense Ministry has established a hotline where families can inquire about a loved one serving in the war zone, and interested citizens can ask about the mobilization and other aspects of military service. Rules for how to claim the remains of a deceased soldier and obtain compensation have also been publicly spelled out.

A New Year’s Eve Ukrainian missile strike on barracks near Donetsk that killed scores of newly mobilized Russian troops provided a stark test of the system. It was quickly admitted by the Defense Ministry, which assured the public that all bereaved families have been informed and will be compensated. It also triggered a major debate in Russian social media over responsibility, which got considerable traction in the wider Russian media.

The public furor over the strike has since died down, but it remains unclear how well the system worked. For example, it appears that none of the three hotline numbers that had been publicized by the Defense Ministry is functioning, after several attempts to access them on Tuesday afternoon.

The RBK news agency cited Andrei Vdovin, the military commissar of Samara, a region on the Volga, as saying that no lists of casualties from the incident will be published “due to the risk of disclosure of personal data and the threat from ‘foreign intelligence’.”

“The government has been learning how to shape the public mood and blunt any impulses to protest,” says Masha Lipman, co-editor of the Russia Post, a journal of Russian affairs in English and Russian. “The Kremlin has always been good at patching and mending; making mistakes and then correcting them. There is a new program of social benefits that soldiers’ families are eligible for. Of course nothing can make up for the loss of a loved one, but compensation counts.”

She cites the recent controversy over Mr. Putin’s “partial mobilization” as an example of both the explosive potential of the conscription issue to generate discontent and the Kremlin’s ongoing ability to contain and redirect any protests.

“There was some public protest over mobilization, and many men left the country, but it faded away,” Ms. Lipman says. “It seemed like the protests were over the disorganization and incompetence of the mobilization rather than being against the war itself. The Kremlin also didn’t stop anyone who wanted to leave. That helped to let off steam, and all those men who left are less of a threat abroad than they would have been if they’d stayed in Russia.”

“They cannot close us with a screen”

The Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers is still active, but far less publicly critical of authorities than in the past. One of its founders, Valentina Melnikova, agreed to talk about the group’s past, but not details of its present activities.

“We never get into military affairs. What matters to us are people,” she says. “When we meet with officials we present a concrete case based on facts and documents. We never invent things. Because of that, officials take us seriously.”

Ms. Melnikova was not invited to the meeting with Mr. Putin. “The story of Putin’s meeting with soldiers’ mothers and the choice of women who participated is yet another attempt to create a counterbalance to the Committee of Soldiers’ Mothers,” she says. “They cannot close us with a screen. There are too many people who have problems with military service, while the state avoids direct contact or serious efforts to solve these problems.”

A number of smaller groups have appeared, such as the Council of Mothers and Wives, whose Telegram channel has become a clearinghouse for news about missing soldiers and criticism of the authorities. But its main organizer, Olga, was also deeply reticent to be named or quoted in an American newspaper.

That is different from the past, when activists saw publicity in Western media as a way of getting the attention of their own authorities. This undoubtedly reflects a growing social mood of fear about the consequences of criticizing the war, but, in at least some cases, there appears to be a genuine mistrust of the foreign journalist’s intentions.

Experts say the dominant public attitude, at least for now, is anxious but not explicitly anti-war.

“Soldiers’ parents from the provinces – and this is where the majority of the mobilized are from – may have a skeptical attitude toward the state, but they prefer not to protest,” says Alexei Makarkin, deputy director of the independent Center for Political Technologies in Moscow. “They instead turn to particular officials to seek help. You can’t appeal to officials while protesting. And sometimes they do help. Not enough, perhaps, but such connections can still work.”

Mexico arrests son of ‘El Chapo’: Why don’t citizens feel safer?

In Mexican towns rife with drug violence, criminals have often claimed to be protectors of the people. Mexicans are increasingly aware that they’ve lived with a false sense of security.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

America Armenta Special contributor

Last week the Mexican government captured Ovidio Guzmán, son of the Sinaloa kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, and his supporters set cars, trucks, and buses ablaze in broad daylight.

It’s not the first time this has happened. Three years ago, the government dramatically botched an attempted arrest of the younger Mr. Guzmán. After his detention sparked gunfights in central plazas, catching unsuspecting civilians in the crosshairs, the government released the Sinaloa cartel heir to restore peace.

That day, referred to as the “Culiacanazo,” marked a turning point for many here, waking citizens up to the reality that neither the cartel nor the government was prioritizing their safety.

”It was the first time in the history of narcotrafficking in Sinaloa when the narcos faced off against civilians,” says Isaac Tomás Guevara Martínez, founder of the Laboratory of Psychosocial Studies of Violence at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa. “They threatened, shot, and killed citizens that had nothing to do with the detention of Ovidio. ... I can’t say all people hate the cartels now, but I think the number of people ... thinking that organized crime is a scourge – that has gone up since 2019.”

This month after another wave of violent retribution, many are left more convinced in the precariousness of their own safety – and that the root causes of drug violence must be addressed.

Mexico arrests son of ‘El Chapo’: Why don’t citizens feel safer?

Lizbeth Angüis, a programmer in her late 20s, grew up in Sinaloa – the Mexican state with a storied history of organized crime, sometimes referred to as the cradle of Mexican drug cartels – hearing messages that drug traffickers are untouchable and that if you support them, they’ll take care of you.

But that myth has been shattered for her – and residents across the northwestern city of Culiacán – as the government has sought to crack down on the Sinaloa cartel.

Last week, after the Mexican government captured Ovidio Guzmán, son of the Sinaloa kingpin Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, his supporters set cars, trash trucks, and public buses ablaze in broad daylight. Nearly 30 soldiers and alleged criminals were killed in gunfire, a grim echo of a deadly revenge attack by cartel members in 2019.

“They don’t care about citizens; they will always take care of themselves first,” says Ms. Angüis.

As President Joe Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau gather with President Andrés Manuel López Obrador this week for the so-called Three Amigos summit, the recapture of Mr. Guzmán is an international victory for Mexico. But if it was a moment of redemption for the government, for citizens in Culiacán it reaffirmed a shifting sense of their own security.

Three years ago, the government dramatically botched an attempted arrest of the younger Mr. Guzmán, releasing the Sinaloa cartel heir after his detention sparked gunfights in central plazas, catching unsuspecting civilians in the crosshairs.

Ultimately the government let him go to restore peace. That day, referred to as the “Culiacanazo,” marked a turning point for many here, waking citizens up to the reality that neither the cartel nor the government was prioritizing their safety. And so this month, amid a second attempt that unleashed another wave of violent retribution, many are left more convinced of the precariousness of their own safety – and that the root causes of drug violence must be addressed.

The Culiacanazo “had important effects on society here, because it was the first time in the history of narcotrafficking in Sinaloa when the narcos faced off against civilians,” says Isaac Tomás Guevara Martínez, founder of the Laboratory of Psychosocial Studies of Violence at the Autonomous University of Sinaloa. “They threatened, shot, and killed citizens that had nothing to do with the detention of Ovidio [Guzmán]. ... I can’t say all people hate the cartels now, but I think the number of people ... thinking that organized crime is a scourge – that has gone up since 2019.”

For many, déjà vu

On Jan. 5, many in Culiacán, the verdant capital of Sinaloa, woke to text messages and news reports simply telling them to stay home. It immediately surfaced dark memories of 2019, when families were separated for hours – barricaded in their offices without access to food or water, shut into clinics that weren’t letting patients in or out, or driving in reverse down one-way streets in an attempt to avoid smoldering roadblocks or armed youths on street corners.

Inés Arce, a local teacher in her early 50s, says the first thing she did this time was to check on her children in their rooms – since her family was separated in 2019 during the violence, a trauma that has stayed with her.

“On both occasions I felt helpless,” says the teacher of the failed arrest in 2019 and last week’s successful early morning operation, which brought Mr. Guzmán to a maximum-security federal prison in Mexico City. “I felt kidnapped in my own city, in my own home ... and to know that my rights as a citizen were trampled because the government needed to detain someone,” she says. “We, the citizens, are the collateral damage. It is us who suffer.”

Indeed, if drug cartels are increasingly distrusted, so too are authorities, especially as a U.S.-backed emphasis on capturing drug kingpins has taken hold over the past 15 years.

Mexico is consistently under pressure to keep drug trafficking organizations, which move billions of dollars in illicit substances across the U.S.-Mexico border each year, in check. But citizens and experts alike question the effectiveness of the most relied-upon policies, such as arresting cartel leaders and deploying the armed forces to halt organized crime.

Over the past decade, the very nature of organized crime has changed, with many groups diversifying their income beyond drug trafficking, and large cartels splintering into smaller, oftentimes more nimble groups.

“With the change in how cartels operate, it’s increasingly unclear what it means to capture a kingpin,” says Jane Esberg, assistant professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania. But, she says, “there’s pretty robust evidence that it doesn’t work. Making weaker cartels doesn’t solve the problem.”

Mr. Guzmán, along with his brothers, is part of a faction of their father’s cartel that emerged after El Chapo’s extradition to the United States in 2017. They’re known as “Los Chapitos,” or The Little Chapos. Ovidio Guzmán’s organization is believed to produce upward of 2,000 kilograms of methamphetamine a month, according to the U.S. State Department.

Mexican officials deny timing last week’s raid to show the U.S. that it’s an active partner in halting the flow of drugs and lethal synthetic opioids across the border. But the U.S. continues to pressure Mexico to take necessary steps to tackle organized crime.

The operation this year was noted for its planning and coordination. Instead of carrying out the arrest in the middle of the city, as in 2019, the government made its move in the town of Jesús Maria, about 27 miles outside Culiacán. And conducting the raid in the early morning meant fewer civilians were on the street, putting them at lower risk.

Nationally, some 42% of Mexicans say the most recent arrest of Mr. Guzmán makes them feel safer, according to an Enkoll poll carried out by El Pais and W Radio. But zooming in on Culiacán, the figures are far lower, with only 17% of the population reporting feeling safer and almost 50% of respondents saying they feel less safe than before the operation.

No longer Robin Hood

This sense of feeling less safe may be a reflection of the difficult memories of what happened in 2019 and being forced to live through that uncertainty again, says Dr. Guevara. But there are also Sinaloans who still look at the presence of the cartel as a sign of security, so losing a leader is nerve-wracking.

“There are still a lot of people [in Sinaloa] who have a little place in their hearts for the cartels. If you look at the situation in Mexico, organized crime groups across the country behave very differently than in Sinaloa. The Sinaloa cartel has a reputation of protecting society and protecting their territory,” he says, unlike newer groups like the Jalisco New Generation, which have a reputation for aggression and violence at any cost.

This idea of the Sinaloa cartel serving as a “Robin Hood” figure – funding schools and health clinics, and even handing out boxes of food and vital supplies during the toughest days of the COVID-19 pandemic – started to break down in 2019.

“People started to look at the cartel in a new light – as a group that threatens the peace,” Dr. Guevara says.

Mr. López Obrador, often referred to as AMLO, took office in 2018 pledging to shift Mexico’s approach to combating organized crime, promising “hugs not bullets.” The only other high-profile arrest during his administration was of Rafael Caro Quintero, who was detained last July – just ahead of a meeting between AMLO and President Biden in Washington.

There are other, effective ways to combat organized crime, argues Dr. Esberg, but they aren’t short-term solutions, which tends to make them politically unappealing.

“The long-term plan, which is hard to implement, is dealing with why people join these groups in the first place. The fact that they can recruit or force an unlimited number of people to join in their fight gives them enormous benefit over the state,” she says. That means dealing with local economies so there are alternative opportunities, and reducing impunity and corruption – no simple tasks.

“The highest cost” of not getting at the root causes behind the power of the cartels, says Dr. Esberg, “is to the people of Mexico.”

A Letter From

Robot pals and AI tools: What’s ahead for tech in the classroom?

How close are we to having technology that could reimagine the way learning is accomplished? The Monitor’s K-12 education reporter visited the recent CES show to see how the gadgetry on display and educator needs match up.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The gadgetry at the CES show in Las Vegas – including charming companion robots and comfortable headsets – is a nod to the ever-changing technology landscape in K-12 education.

Schools once tiptoeing toward adoption began a sprint at the onset of the pandemic. And even though remote learning has faded somewhat, the technology conversation has intensified.

Teachers aren’t just grappling with how and when to embrace digital learning methods. They’re also eyeing innovations in artificial intelligence. Last week, the New York City Department of Education blocked access on district networks and devices to ChatGPT, a new AI-enabled program.

And if a stroll through CES – held Jan. 5-8 – is any indication, the disruptions will continue in big and small ways. Roybi Inc. debuted its RoybiVerse, which the company describes as an “intelligent edutainment metaverse.” “Immersive education is the future of learning,” says Elnaz Sarraf, Roybi CEO, in an email.

Despite concerns about tools like ChatGPT writing students’ essays, Lindy Hockenbary, a teacher-turned-ed-tech consultant, says there’s also room for hope. “It’s disruptive to the way we do formal education now,” she says. “But the other part of it – and where it can truly transform education – is it does have the power to help with personalized learning.”

Robot pals and AI tools: What’s ahead for tech in the classroom?

It’s hard not to smile back at Buddy.

He’s sitting on the convention floor at CES, the large technology conference formerly known as the Consumer Electronic Show, in Las Vegas. His white body rotates and his head swivels, but it’s his emotive face that melts hearts. The robot smiles, frowns, blinks, and even tears up – digitally, of course.

His Paris-based creator, Blue Frog Robotics, bills him as an “emotional companion” that can solve problems faced by education systems.

For example, Buddy sits on desks and becomes a homebound or hospitalized child’s avatar, providing the classroom experience in a more natural way. Last year, France’s Ministry of Education ordered roughly 2,000 of the artificial intelligence-enhanced robots for that purpose, says Maud Verraes, the Paris-based company’s chief marketing officer.

“There’s a big need, and it’s the same everywhere,” Ms. Verraes says of using the robot to give children a virtual presence in classrooms.

Buddy’s inclusion among the aisles of futuristic gadgets at CES nods to the ever-changing technology landscape in K-12 education. Schools once tiptoeing toward adopting technology began a sprint at the onset of the pandemic. And even though remote learning has faded somewhat, the technology conversation has intensified.

Teachers aren’t just grappling with how and when to embrace digital learning methods. They’re also eyeing educational integrity threats posed by artificial intelligence. Last week, the New York City Department of Education blocked access on district networks and devices to ChatGPT, an AI-enabled program released to the public in November.

Despite concerns about tools like ChatGPT writing students’ essays, Lindy Hockenbary, a classroom teacher-turned-education-technology consultant, says there’s also room for hope. The same artificial intelligence technology powering those programs could help identify students’ academic strong and weak spots. In theory, they could flag a student struggling to understand fractions, alerting the teacher that more support or practice is needed.

“It’s disruptive to the way we do formal education now,” she says. “But the other part of it – and where it can truly transform education – is it does have the power to help with personalized learning.”

And if a stroll through CES – held Jan. 5-8 – is any indication, the disruptions will continue in big and small ways. Roybi Inc., the creator of an educational robot, debuted its RoybiVerse, which the company describes as an “intelligent edutainment metaverse.”

Picture a virtual universe with dazzling animation and characters. The immersive learning platform aims to engage students and empower them to learn at their own pace through interactivity, says Elnaz Sarraf, founder and CEO of Roybi. The company expects to launch its RoybiVerse first on virtual reality headsets and then computers.

“Immersive education is the future of learning,” says Ms. Sarraf via email. “Students can get into the virtual worlds, collaborate, interact and learn together while educators can easily make their content available at anytime and anywhere in the world.”

How much (or little) of the classroom experience will migrate to the metaverse is difficult to say. Internet connectivity issues still challenge some schools, especially in rural areas. Other schools haven’t yet achieved the coveted ratio of one laptop or tablet for every child. Some of that boils down to cost.

That’s why technology isn’t always top of mind for Vicki Kreidel, a Las Vegas reading specialist whose elementary school sits about 8 miles northeast of where tech gurus gathered for CES. She has embraced some tech – taking kids on virtual field trips, for example – but says schools need more basic resources before fancy gadgets.

“I think as educators, we need to stand up and say, ‘You know what? That’s not really useful. We could use more books,’” she says.

Ms. Hockenbary, who helps K-12 educators leverage technology for learning purposes, grounds her approach with this needs-based question: How will it benefit the student?

“You’re using it as a way to help your students get from A to B, right? – helping them reach a learning goal,” she says. “And I think that big picture focus gets lost a lot in all of the hubbub.”

Unlike Buddy, a previous CES innovation winner that can also teach kids to code (current price in the business world: $3,000), some of the other ed-focused items on display at the packed show simply adapt or reimagine existing products, with the aim of making learning easier or more attainable.

Jin Sub Oh, the founder of Seoul-based Bengdii, hopes to do well with his pastel-hued headset that offers comfort to student ears. Mr. Oh says the product was born out of the pandemic-related foray into remote learning.

“I have two sons,” he says. “They hate wearing headsets.”

They dislike the pressure, he says. So the Bengdii Bee, newly available for about $50, features earpieces that can cover or flip away from the ear.

Glitzy tech products aren’t always a prerequisite for student engagement and learning, says Jordana McCudden, an assistant principal at an elementary school in Las Vegas. She has seen students’ reading and math skills increase after using digital learning programs on Chromebooks or tablets. On the flip side, she recently reminded her college-age son to take notes by hand, given the learning benefits of doing so.

After hearing about some of the gadgetry featured at CES, Ms. McCudden praises the Buddy robot and the headsets that take pressure off of kids’ ears. But she also expresses disappointment that the pandemic struggles didn’t prompt greater innovation about how to digitally connect students and teachers in a way that is “fluid and easy and not one more thing for a teacher to do.”

She says she looks for the harmony between education and technology, while also acknowledging the role the latter plays all around us. In her own home, she can voice a question and have an artificial intelligence-powered device promptly reply. But technology should not supplant the teacher, she says, nor should it stifle discourse or collaboration among students.

“I love that ... my kids have access to [home technology], and I think it’s enhanced their lives,” she says. “But we have to maintain that balance of humanity and human connection and the value in talking out our ideas and processing together and having vigorous debate.”

Points of Progress

Power unlocked: Debt funds wildlife, refugee brings solar to camp

When expectations of the norm are left by the wayside, achievement also loses boundaries. In our progress roundup, one refugee’s efforts lift the entrepreneurship of others; and women leave the sidelines to referee one of the world’s top sporting events.

Power unlocked: Debt funds wildlife, refugee brings solar to camp

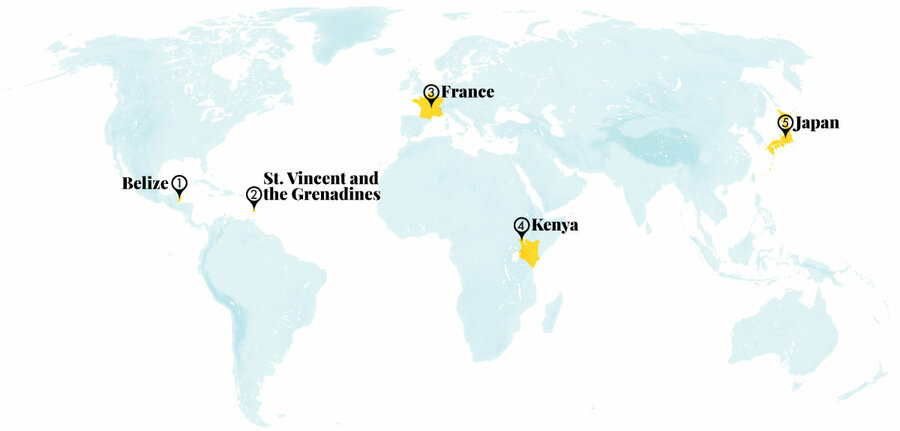

1. Belize

A vigorous model of debt restructuring is freeing up funds for marine conservation. Belize has long lacked resources for environmental protection, so it was a good candidate for the Blue Bonds for Ocean Conservation, a financial mechanism pursued by The Nature Conservancy.

The plan allowed Belize to restructure $553 million of the country’s debt in 2021, and it is expected to generate $4 million annually for environmental protection over two decades. In exchange, Belize has committed to protecting a minimum of 30% of its marine territory and strengthening its management of conservation sites.

Coral reefs are a major draw for tourism, which constitutes 40% of the country’s economy. But that revenue is no longer enough to live by. The blue bond is also supporting local initiatives for economic empowerment, such as seaweed farming.

Prime Minister Juan Antonio Briceño celebrated the relationship between environmental work and economics: “We can show that conservation is good business and that it can have a direct impact on the people most affected by climate change.” The refinancing model first proved successful in the Seychelles and was approved in Barbados last fall.

Source: The Nature Conservancy

2. St. Vincent and the Grenadines

The Union Island gecko has nearly doubled its population since 2018. Famous for its intricate, colorful markings, the tiny gecko has been a favorite among exotic pet collectors since it was first spotted in 2005. Over the next decade, it became one of the most trafficked reptiles in the Eastern Caribbean, losing four-fifths of its population.

Fauna & Flora International, along with Re:wild, local nonprofits, and the forestry department, hashed out a species recovery plan. Together they worked to improve the management of protected areas and bolster anti-poaching patrols and camera surveillance. Now there are an estimated 18,000 geckos, up from 10,000 in 2018.

“Our shared, unwavering dedication and sacrifice has brought us this far,” said Roseman Adams, co-founder of the local Union Island Environmental Alliance. “We now have to be entirely consistent with further improvements in our management and protection of the gecko’s habitat for this success to be maintained.”

Source: Mongabay

3. France

Stéphanie Frappart became the first woman to referee a men’s World Cup match. Ms. Frappart, with assistant referees Neuza Back of Brazil and Karen Diaz Medina of Mexico, officiated the Dec. 1 match between Germany and Costa Rica. The three officials also made history together as the first all-female referee team. Some 70,000 fans watched at Al Bayt Stadium in Qatar.

Ms. Frappart said she was surprised to be selected for the role, although she has refereed games in the Champions League and the Women’s World Cup. She began officiating at age 19 and has earned a top-notch reputation over two decades. Pierluigi Collina, the chairman of the FIFA referee committee, said last year about the referee’s trailblazing, “I hope that there will be more Frapparts in the future and that this will no longer constitute an oddity or news story.” The 2022 World Cup referee roster included a total of six women.

Sources: The Guardian, Corriere Della Sera

4. Kenya

Solar-powered internet is helping refugees in Kenya study and work online. The refugee settlement of Kakuma in northwestern Kenya is home to 200,000 long-term refugees from 19 countries. One resident, Innocent Tshilombo, began looking into solar energy following years of limited opportunities for employment or movement. He scraped together money of his own and seed grants to buy a solar panel, an internet node, and a battery backup. Then he taught himself how to put it all together.

Today 17 of these nodes provide internet access to 1,700 residents in the Kakuma settlement. Users pay $5 a month, and many are learning skills from computer science to graphic design and looking for work online. Mr. Tshilombo earned a business administration degree from the free online University of the People, while others are using solar energy to power their local businesses. Finding enough digital work is the next challenge, since competition for jobs with residents outside the camp can be a source of tension. “People have enough time that they can learn big things and do big things if they’re given the right platform,” said the entrepreneur.

Source: Context

5. Japan

With robots, Japanese children can participate in the classroom from afar. Kids who can’t attend school choose an avatar that appears on a remote-controlled robot, which they guide around the classroom, on campus, and even on field trips. To help create a realistic presence, the Telerobo turns its “head” when directed and chats with others.

The project was developed so that students requiring extended hospital stays could keep in touch with the school community. The public-private partnership between iPresence and the New Media Development Association plans to expand use of the robots to help children with disabilities. “The purpose of school life is not just about learning, but also communicating with teachers and friends,” said Telerobo project leader Michihiro Hayashi.

Source: JSTORIES

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why Brazil dodged a coup

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Military coups against elected leaders have hardly gone out of favor. So it is worth asking why the top brass in Brazil, the world’s fifth-largest democracy that only a few decades ago was under junta rule, didn’t take the bait from thousands of protesters Sunday asking officers to join them as rioters briefly took over the capital’s main buildings in an attempt to roll back a presidential election.

For weeks before the winning candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office Jan. 1, protesters had camped outside army barracks in Brasília hoping the military would keep the losing candidate, President Jair Bolsonaro, in power. “When it came down to it, the armed forces were quiet,” wrote University of Denver scholar Rafael Ioris.

Many militaries around the world have come to realize that a duty to defend national sovereignty with force of arms must run secondary to civilian rule based on ideals such as individual sovereignty, civic equality, and peaceful resolution of disputes. Democracies may falter or their economies weaken, but might does not make right.

Staying in the barracks despite the protesters’ pleas to join them was the military’s best way to uphold Brazil’s democracy.

Why Brazil dodged a coup

Military coups against elected leaders have hardly gone out of favor – see Myanmar, Egypt, and multiple African countries, even an attempt in Germany last month to incite an army rebellion. So it is worth asking why the top brass in Brazil, the world’s fifth-largest democracy that only a few decades ago was under junta rule, didn’t take the bait from thousands of protesters Sunday asking officers to join them as rioters briefly took over the capital’s main buildings in an attempt to roll back a presidential election.

For weeks before the winning candidate Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office Jan. 1, protesters had camped outside army barracks in Brasília hoping the military would keep the losing candidate, far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, in power. And that, despite a statement from three commanders of Brazil’s armed forces after the Oct. 30 election saying solutions to the country’s disputes must come from the democratic rule of law.

“When it came down to it, the armed forces were quiet,” wrote University of Denver scholar Rafael Ioris in The Conversation. “The idea of a traditional coup – tanks on the streets stuff – that just didn’t happen.” On Sunday, military forces ended up helping detain hundreds of the most violent protesters. While some in the military’s lower ranks may believe in Mr. Bolsonaro’s social causes, those in the higher ranks were not willing to overthrow a legitimate election, political commentator Tanguy Baghdadi told The Grid.

Many militaries around the world have come to realize that a duty to defend national sovereignty with force of arms must run secondary to civilian rule based on ideals such as individual sovereignty, civic equality, and peaceful resolution of disputes. Democracies may falter or their economies weaken, but might does not make right. Ballots are a far greater source of legitimacy than bullets.

During his presidency, Mr. Bolsonaro, a former Army captain, appointed thousands of current and former military officers to government posts. Many of them at the top ended up resigning because of the president’s tactics. Mr. Bolsonaro would often refer to “my” military.

The new president, who won over many in the military during his previous terms in office (2003-10), plans to restore healthy civilian control over the rank and file. “The depoliticization, and more, the non-partisanship of the armed forces is absolutely necessary for the country,” said José Múcio Monteiro, a career politician appointed as defense minister.

Brazil has now avoided what could have been one in a rich history of Latin American coups, in part because its military respects the supremacy of elected, civilian power. Such power begins – and ends – with ideals embedded in a democratic constitution, even if sometimes poorly practiced.

Staying in the barracks despite the protesters’ pleas to join them was the military’s best way to uphold Brazil’s democracy.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘The most wonderful time of the year’?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Curtis Wahlberg

Rather than feeling let down after the holidays, we can recognize the potential, each moment, to be filled with the spirit of Christ and to share God’s goodness with the world.

‘The most wonderful time of the year’?

Similar to when I was a kid and didn’t have school around Christmastime, I took things a little easier over the holidays. Our oldest daughter came home for a week. The family sang around the piano. At church, the services spoke of the great hope and promise available to us thanks to God’s Christ. I could certainly see why a popular Christmas song declares, “It’s the most wonderful time of the year.”

And yet, I also see the need to challenge this sentiment in a way.

Over the years, my family’s experiences with colds and flus have strongly coincided with the letdown in the time after Christmas. It can feel as if the post-holiday blues have an effect on our health and well-being. My family has always turned to prayer in these instances and consistently found a rallying spirit that has brought physical healing, joy, and even lessons to be learned.

These healings aren’t the result of waiting for the warmer spring to arrive. They happen when the new spring of spiritually insightful thought helps us understand something differently – including realizing that the most wonderful time of the year is always possible when we fully embrace the good that God ceaselessly has for us. Since God is constant and ever present, so is His goodness.

The Bible speaks of God as Love and Spirit. It’s been helpful to me, and to many others I know, to understand everyone’s true nature as an expression of this Love and Spirit. In finding deeper awareness of the nature of God and of ourselves, there comes a realization that the really meaningful and strengthening stuff of life is always available to be brought forth in everyone, at any time. We indeed can – and are needed to – find joy in expressing God’s qualities of intelligence, creativity, grace, and so on, to light up our world for everyone’s benefit, not just at Christmastime but always.

One reason December can feel like such a wonderful time of the year is that the many festivities can help to distract us from the world’s ongoing challenges. Then post-December comes, and we’re reminded of these challenges again. But we can face the demands for a new year of progress with the determination to help the world feel more of God’s presence and unstoppable good purpose for all.

I have found no better help in this effort than turning my thinking to the Christ, the spiritual idea of God that Jesus represented, to realize the fullness of our spirituality. I cling to this assurance from the book of Hebrews: “We continue to share in all that Christ has for us so long as we steadily maintain until the end the trust with which we began” (3:14, J. B. Phillips, “The New Testament in Modern English”).

So here I am now, during another post-holiday season, cherishing the timeless ability to express God’s qualities. It seems particularly imperative to do this now, not only for myself but for the world. What if we began to identify the most wonderful time of the year not as the time with the most festivities but as every moment we have available to us to experience and share what the Christ has for us? (That’s every moment.)

This new way of identifying wonderfulness can be a big step for folks. It certainly has been for me. Big or small, the best moments come when we’re filled with something spiritual, helpful, purposeful.

This is what Mary Baker Eddy saw in the Science of the Christ that she endeavored to share with the world. She wrote, “To live so as to keep human consciousness in constant relation with the divine, the spiritual, and the eternal, is to individualize infinite power; and this is Christian Science” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 160).

Indeed, the most wonderful time of the year is every moment throughout the year in which we let our spiritual purpose of magnifying God come forward and express God’s great qualities of good.

A message of love

More than a downpour

A look ahead

Come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a story about how other countries have handled prosecutions of former presidents.