- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Freedom vs. responsibility? Musk and EU butt heads over online rules.

- Moral moments matter: The power of individual choice

- College while in high school: How dual credit is aiming for equity

- Civics in the shadow of Capitol Hill. A letter from a D.C. high school.

- Iranian director’s poignant film champions freedom to create

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Behind FAA ground stoppage, a changing view of safety

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

On Wednesday, the federal authorities grounded all air traffic in the United States for the first time since 9/11 – for something some pilots look at as little more than spam.

The grounding took place when a notification system known as NOTAM – or, Notice to Air Missions – failed. NOTAMs alert pilots of changing conditions and hazards, such as closed runways, air shows, or temporary cranes near airports. They’ve been around for decades, but in recent years, NOTAMs have been jammed with so many items that some pilots ignore them.

At an International Civil Aviation Organization hearing on the subject last year, a former air traffic controller noted that a typical briefing package for a flight from Munich to Singapore could include 120 pages of NOTAMs, with 10 to 15 alerts per page.“For every single one, we should read, understand, and decide if it’s relevant for our flight,” Finnair Capt. Lauri Soini told the hearing, according to FlightGlobal, an industry publication.

Most aren’t relevant, which means a pilot – who often has about 20 minutes for pre-flight briefing – would need to read 90 minutes of NOTAMs, he added.

Work is ongoing to reform NOTAMs. But the grounding Wednesday reveals something about the nature of air travel today. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg said it was “out of an abundance of caution.” Authorities say there is no evidence yet of foul play.

Shutting down all U.S. airspace for NOTAMs might seem extreme, especially considering the disruptions. But consider that the last fatal crash of a U.S. airliner was in 2009. And in 2017, a missed NOTAM nearly led an airliner to landing on a full taxiway in San Francisco.

Amid cancellations and delays, it’s worth remembering that “an abundance of caution” across the industry has dramatically transformed our sense of safety in the air.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Freedom vs. responsibility? Musk and EU butt heads over online rules.

Elon Musk seems to want to run Twitter like a classic American forum for speech. There’s a problem: Twitter is global, and Europe plans to impose the responsibility it thinks such forums require.

Twitter and the European Union appear to be on a collision course, thanks to the world’s most ambitious plan to date to govern what happens online. And ambition may be what the EU will need if it plans to take on Twitter owner Elon Musk.

Mr. Musk has personally spread misinformation online. He’s let a number of far-right figures banned from the platform back on, after promising to install a committee to decide such matters. Just before the December holidays, he deactivated the accounts of a group of journalists who were covering him, only to reinstate some of them days later.

All are potential violations of the EU’s new Digital Services Act (DSA). The act has been praised as the best of all the policy attempts so far to check the online Wild West. Twitter could be the first real-world test for the act, and its case will inform global policymaking.

“The DSA is trying to create a kind of regulatory ecosystem for an extremely dynamic, extremely fluid space,” says technology expert Tyson Barker. “They’re saying we need a trustworthy [online] environment, and trustworthy environments require clear rules and impartial enforcement. And that is exactly what you’re not getting with Elon Musk.”

Freedom vs. responsibility? Musk and EU butt heads over online rules.

Elon Musk’s face-off with Europe started, fittingly, with a tweet. Having completed his $44 billion purchase of Twitter, he announced Oct. 28: “The bird is freed.”

The European Union’s internal market commissioner, Thierry Breton, immediately tweeted back: “In Europe, the bird will fly by our [EU] rules.”

That exchange signaled the apparent collision course Twitter is set upon with the EU, whose regulators are behind the world’s most ambitious plan to date to govern what happens online. And ambition may be what they’ll need if they plan to take on a billionaire with a libertarian bent toward speech, a habit of online trolling, and near absolute power over a global social media platform.

Mr. Musk has personally antagonized prominent people and spread misinformation online. He’s let a number of far-right figures and others banned from the platform back on – including President Donald Trump, Andrew Tate, and Jordan Peterson – after promising to install a committee to decide such matters. Just before the December holidays, he deactivated the accounts of a group of journalists who were covering him, only to reinstate some of them days later after online backlash. All are potential violations of the EU’s new Digital Services Act.

The DSA, which is meant to split the difference between an American view and the view of nations like Germany on how to regulate online environments, has been praised as the best of all the policy attempts so far to check the online Wild West. Yet the agile regulatory ecosystem it imposes – a framework that includes government, civil society, and users checking each other – is a year or two from being fully implemented. Twitter could be the first real-world test for checking the true power of the act, and its case will inform global policymaking.

“It’s hard to know what Elon Musk is doing – it feels like he’s trying to crash this thing,” says Tyson Barker, a technology expert and senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. “The DSA is trying to create a kind of regulatory ecosystem for an extremely dynamic, extremely fluid space. ... They don’t want to be the truth police or a censor. They’re saying we need a trustworthy [online] environment, and trustworthy environments require clear rules and impartial enforcement. And that is exactly what you’re not getting with Elon Musk.”

Benefits and societal risks

The DSA is Europe’s behemoth of an attempt to catch up with a world in which much happens online.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought into newfound focus the danger of online misinformation, as governments tried to get people to mask up or vaccinate. But even before the coronavirus upended society around the world, European member states could point to online behavior with real-life consequences, whether it was the rise of Germany’s far right via online misinformation and Islamophobic campaigns, or France’s 2017 presidential elections being marred by information manipulation.

“While online platforms offer great benefits to users, they are also the source of great societal risks such as illegal content or dangerous goods,” says Charles Manoury, an EU digital economy spokesperson. The DSA will make sure platforms’ “power over public debate is subject to democratically validated rules.” The EU’s basic premise is that legislation must evolve to protect fundamental rights online.

Rather than mandate what’s legal or not, the DSA sets clear boundaries for the digital space in a variety of aspects, and then delegates the responsibility of regulation to an ecosystem of actors. That ecosystem includes researchers who – with newfound access to data provided by the platforms under the DSA – are put in the position of “both pathfinders and as quasi-auditors,” said Mathias Vermeulen, public policy director at the data rights agency AWO, in an online forum hosted by the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

In effect, the DSA won’t have the EU moderate illegal speech, but instead requires platforms to report transparently on their own efforts. Platforms large enough to fall under its umbrella will need to assess all kinds of risks, including disinformation and hate speech. They must also hand over data related to the platforms’ powerful algorithms at the request of a regulator, a groundbreaking requirement that would allow scrutiny from experts in their respective fields.

“For instance, to what extent does YouTube amplify or recommend COVID-19 misinformation?” says Dr. Vermeulen. “Companies will have to address these risks. They need to sort of identify, analyze, and assess any systemic risk related to things like design, functioning, or use of their services. And then we talk about this information.”

The DSA represents a middle ground in governmental regulation of online environments. On opposite sides of the philosophical spectrum are the Americans and Germans. The Germans believe it’s the responsibility of government to regulate the internet, contrary to the American tradition that government should stay out of regulating such things as private speech. The U.S. approach is currently to place responsibility on platforms themselves to create rules and abide by them.

In other words, Mr. Musk is headed for trouble, say experts. “We have to worry,” says Annika Baumann, a social media expert at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society. “The actions he’s currently undertaken do not follow the intention of EU rules.”

And while the DSA can’t be copied wholesale because of differences in countries’ legal contexts, certain aspects are “extremely admired in the United States,” says Mr. Barker, the technology expert, “including the fact that it’s not looking to regulate speech. ... It’s looking to regulate terms of service and create transparency and create access to data and create accountability and risk assessments.”

Its rules on access to data will be another area in which U.S. lawmakers are engaging, say experts. “In the U.S., that is sort of a relatively bipartisan topic where both Republicans and Democrats can see the value and could agree on potentially one form of legislation,” says Dr. Vermeulen, the data rights public policy expert. “It’s accepted by a wide range of regulators that it’s really essential to gain more information about the potential harms or even positive effects of the use of a service in a specific jurisdiction.”

A confrontation brewing?

Observers say that if Twitter continues as it has been under Mr. Musk, it will almost certainly run afoul of the DSA once it comes fully online in 2023 and 2024.

Mr. Musk has jettisoned half of Twitter’s workforce, including workers who liaised with Brussels and oversaw content moderation. Twitter’s heads of departments including legal, policy, and trust and safety have either resigned or been fired. “One of my limits was if Twitter starts being ruled by dictatorial edict rather than by policy. ... There’s no longer a need for me in my role, doing what I do,” said Twitter’s former head of trust and safety, Yoel Roth, in an interview following his resignation.

“[Mr. Musk] laid off a large part of his staff that dealt with regulations, and his data protection officer was gone before naming a new acting one,” says Dr. Baumann, the social media expert. “These are very important things to have for a platform.”

Commissioner Breton tweeted in November a list of things Twitter needed to start with: “implement transparent user policies, significantly reinforce content moderation and tackle disinformation.”

Meanwhile, users rejoicing in Mr. Musk’s “anything goes online” approach have spotted opportunities to engage in once-unacceptable behavior. Within hours of Mr. Musk’s takeover, the number of “vulgar and hostile” posts based on race, religion, ethnicity, or sexual orientation skyrocketed. And just as winter approached, Twitter announced it would no longer police the spread of misinformation about COVID-19. Mr. Musk himself has tweeted content that would likely be in violation of European regulations, and also pushed targeted ads, regarded by the EU as a form of online surveillance.

The DSA has teeth: Violations can result in penalties of up to 6% of global annual turnover, meaning tens of millions of dollars for a company such as Twitter. When Mr. Musk arbitrarily suspended the accounts of several tech journalists who cover him, an EU official fired a shot across Twitter’s bow. “EU’s Digital Services Act requires respect of media freedom and fundamental rights. ... There are red lines. And sanctions soon,” tweeted Vera Jourova, the European Commission’s vice president for values and transparency.

What’s groundbreaking about the EU’s approach is that most current attempts to regulate the digital space rely upon public-private partnership and cooperation. Yet governments don’t have the resources or knowledge to moderate content on platforms, and platforms don’t have the incentive or political will to do so, says Heather Dannyelle Thompson, manager for digital democracy at the Berlin-based research firm Democracy Reporting International. “That’s why the DSA is a landmark in the absence of meaningful legislation from the [U.S.], the birthplace of many of the most prominent internet companies.”

“There is room for them to evade”

Still, there are potential loopholes for Twitter to take advantage of. First, the infrastructure of the EU’s plans – a central board, along with a national coordinator in each of the 27 member states, which will cooperate to supervise platforms and other entities in implementing the DSA – is cumbersome, with no real clarity yet on how enforcement will happen. “The intentions are very clear and very good, but we have to see how they work out,” says Dr. Baumann, referring to the work that needs to be done as a “bureaucratic monster.” “In Germany alone, in one year, there have been more than 20,000 instances [reported to state media authorities] where this board would have to take actions. There will be a lot of work.”

It’s also unclear whether Twitter, which by some reports has seen more than a million users leave the service since Mr. Musk’s takeover, will continue to qualify as a “very large online platform (VLOP)” under DSA rules. Being a VLOP – essentially, reaching 45 million people – is necessary for EU regulators to impose some of the DSA’s most powerful enforcement tools. (The EU does have latitude to apply the VLOP label outside the reach requirements, however.)

There is also speculation that Twitter could choose to incorporate in an EU member state with looser regulation and enforcement, says Ms. Thompson of Democracy Reporting International. “It’s currently [in] Ireland, but could be changed in a move of political maneuvering,” she says. “No one currently knows how Twitter will position itself. But ... there is room for them to evade.”

EU regulators must also decide fuzzier issues, such as whether failing to enforce a clear policy combating COVID-19 misinformation constitutes a breach. And, so, the saga will continue to unfold.

“If Twitter is still alive and kicking in a year when all the tenets of the DSA come into place, and still behaving in this kind of very capricious way, governed by one person with no compliance officers ... they’re going to be in for a world of hurt,” says Mr. Barker.

Mr. Musk has so far been quiet in January, with no blatant violations of EU policy. But he did tweet a prediction about 2023: “One thing’s for sure, it won’t be boring.”

Patterns

Moral moments matter: The power of individual choice

Against a somber geopolitical background, moments of moral clarity illuminated the scene in 2022, as individuals did what they felt was the right thing to do.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Big speeches and policy summits tend to grab the headlines. But just as consequential, sometimes, are the actions and decisions that individuals take – not from any conscious desire to act heroically, but simply because they felt like the right thing to do.

Two such moments stood out in 2022.

The first came on Feb. 26. It comprised just six words. Turning down an American offer to evacuate him from Kyiv, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy said simply, “I need ammunition, not a ride.” That set the tone for Ukraine’s subsequent fortitude.

Later in the year, former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson experienced her own moment of moral clarity when she decided to stop prevaricating and tell the congressional inquiry into the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol what had been going on that day in the White House.

Withholding information, she felt, was the same as lying. She could not live with that knowledge. In the words of a friend, that would have meant “failing the mirror test” – being unable to face herself.

Often, such individual actions don’t directly alter the course of events.

But they do convey a powerful message: That such choices of conscience, however difficult, are possible. And that not acting is also a choice.

Moral moments matter: The power of individual choice

They may sometimes seem trivial: a few words spoken over the phone, or scrawled across a sheet of paper.

But they can be as consequential as any of the speeches and policy pronouncements that dominate our discussion of world politics.

They are the actions and decisions that individuals take – not from any conscious desire to act heroically, but simply because they felt like the right thing to do.

And as we turn the page from the fraught geopolitics of 2022, it is worth stepping back and recognizing the significance – and lasting power – of such moments of moral clarity.

Two in particular stand out like bookends in the tumultuous year that has just ended.

The first came on Feb. 26. It comprised just six words, from a former comedian and television actor who, in an extraordinary career change, had become the president of Ukraine.

Forty-eight hours earlier, Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s country had suffered a full-scale Russian invasion aimed at eliminating both him and an independent Ukraine. His key ally, America, was offering to evacuate him so he could lead the resistance from abroad.

The obvious response seemed a grateful “yes.” Russia was pushing tens of thousands of troops across the border, and had many more tanks, missiles, and aircraft than Ukraine could muster.

Instead, Mr. Zelenskyy turned Washington down, with a reply that set the tone for Ukraine’s fortitude. “I need ammunition, not a ride.”

That same sense of clarity distinguished the even more unlikely protagonist in the year’s other bookend moment, which involved the inquiry into the Jan. 6, 2021 mob assault on the U.S. Capitol.

Cassidy Hutchinson had been in her mid-20s, just out of college. But after interning on Capitol Hill and in Donald Trump’s White House, she’d become the top aide to his chief-of-staff, Mark Meadows.

She is now known to millions of Americans. Her public testimony made her the Jan. 6 inquiry’s star witness to what was going on at the highest levels in the White House before, during, and after the attack on the Capitol.

But at least as compelling is the soul-searching that led her to provide that account – revealed in the transcript, released late last year, of a closed-door conversation with the committee.

In two earlier appearances, she had answered many of the inquiry panel’s questions by saying she simply “didn’t recall.” She’d been reassured by her lawyer that this wasn’t actually lying. And besides, the committee couldn’t know what she did or didn’t remember.

Yet in her own mind, this was lying. It was wrong. And even if the committee didn’t know she was withholding information, she knew.

So ultimately, she decided that despite pressure to hold the line, and an abiding loyalty to Mr. Meadows and others in the White House, she could not live with that knowledge. In the eloquent words of a friend in whom she’d confided, that would have meant “failing the mirror test” – being unable to face herself.

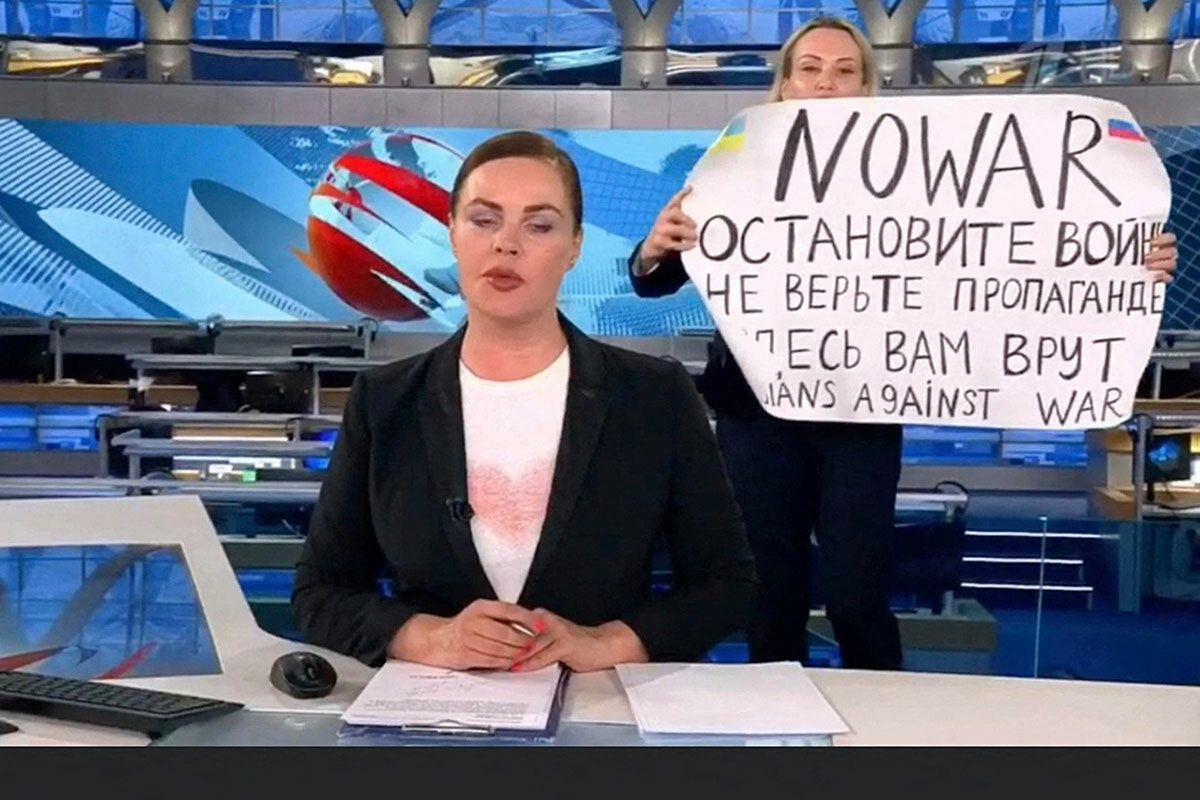

That kind of internal reckoning has also led others to speak out over the past year when silence would have been easier, people like Moscow television producer Marina Ovsyannikova. A few weeks into President Vladimir Putin’s war on Ukraine, she strode onto the set of Russia’s main nightly news broadcast holding a sign saying: “No war! Don’t believe the propaganda. They’re lying to you here.”

Or like the young Chinese citizens who stood holding blank sheets of paper, to dramatize the government’s draconian censorship regime, during the protests that helped persuade President Xi Jinping to abandon his “zero-COVID” lockdowns.

And the countless Iranians who, despite a violent crackdown by security forces, have persisted in chanting their support for “women … life … freedom.”

Often, such individual actions don’t directly alter the course of events.

But they do convey a powerful message: That such choices of conscience, however difficult, are possible. And that not acting is also a choice.

Recent history – the ethnic slaughters in Bosnia and Rwanda in the 1990s, and Nazi Germany’s mass murder of the Jews of Europe in the 1940s – has reinforced that message on an even larger scale.

During each of these atrocities some people stood out from their neighbors by making a choice of conscience, often risking their lives to help the victims. A filmmaker friend of mine documented one especially moving example: the inhabitants of the southern French village of Chambon-sur-Lignon, who hid and ultimately saved thousands of Jews during the Nazi occupation.

Tragically, many more people abetted the killing in Bosnia, Rwanda, and Europe than tried to hinder it.

Yet the role of another group, larger than either, was also critical to what happened. As the late Nobel-winning author and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel memorably said of all genocides, “what hurts the victim most is not the cruelty of the oppressor.”

Rather, he said, it was “the silence of the bystander.”

College while in high school: How dual credit is aiming for equity

The option of taking college courses while in high school is booming in the U.S. What will it take to transform dual credit learning into a true tool to advance equity?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Kelly Field Contributor

Once seen as a way to stave off “senioritis” among top students, the “dual credit” option – which allows high schoolers to take college courses – is booming in the United States, driven by a quest to lower the time and cost of a college degree.

The opportunity is now widely viewed as a tool to advance equity, with the potential to close long-standing racial and socioeconomic gaps in college completion.

Yet in much of the country, the courses still aren’t reaching many of the low-income, rural, and minority students who might benefit from them the most. Now, in the midst of a pandemic that is causing disproportionate numbers of low-income students to put off college, some states, colleges, and school districts are tackling those barriers head-on, lowering costs, relaxing strict entrance requirements, and aggressively recruiting underrepresented students into the programs.

Community colleges in particular have seen a rise in dually enrolled students, whose ranks grew by 11.5% this past fall, data from the National Student Clearinghouse shows. Some of those schools are now experimenting with offering young people a path to a credential.

“When students have a sense of purpose,” says the Aspen Institute’s Josh Wyner, “they’re more likely to finish their degrees.”

College while in high school: How dual credit is aiming for equity

Rafael Sierra, a high schooler in Baytown, Texas, has never been one to skate through life – or school. When things get tough, he’ll hear his father saying “ponte las pilas” – “put the batteries in” – and knuckle down.

So when he was told by a middle school teacher that he could take college courses in high school, for free, he jumped at the chance. He saw it as a way to be challenged, to save money on college tuition, and, above all, to make his Mexican immigrant parents and three older siblings, who paved his path to college, proud.

Five years – and nearly 50 credits – later, Rafael is part of a nationwide boom in “dual credit” learning being driven by a quest to lower the time and cost of a college degree. Almost four decades after Minnesota launched the first statewide program, a majority of high schools offer dual credit, and roughly 10% of their students take them, federal data shows.

Once seen as a way to stave off “senioritis” among top students, the dual credit option is now widely viewed as a tool to advance equity, with the potential to close long-standing racial and socioeconomic gaps in college completion. Studies show that students who take the courses are more likely to enroll in and finish college than those who don’t.

Yet in much of the country, the courses still aren’t reaching many of the low-income, rural, and minority students who might benefit from them the most. Though about one-third of white students took at least one dual credit class in 2019, only about a quarter of Hispanic, Asian, and Native American students, and almost a fifth of Black students, did.

These long-standing gaps have been attributed to everything from the programs’ cost and eligibility criteria, to teacher shortages, to a lingering misperception that the courses are for gifted students only.

Now, in the midst of a pandemic that is causing disproportionate numbers of low-income students to put off college, some states, colleges, and school districts are tackling those barriers head-on, lowering costs, relaxing strict entrance requirements, and aggressively recruiting underrepresented students into the programs. Lee College, which provides the courses at Rafael’s school, has begun accepting students on the cusp of eligibility who have the motivation and support to succeed in a college-level course, according to Marissa Moreno, executive director of school and college partnerships.

In Ohio, community colleges are seeking a state waiver to expand options for admission to technical programs beyond the current test score and grade requirements, as Intel and other local employers clamor for more skilled workers, says Marcia Ballinger, president of Lorain County Community College in Elyria.

“Some kids are not good test-takers,” adds Ann Schloss, superintendent of the county’s Elyria City School District, “but that doesn’t always mean they won’t be able to succeed in the class.”

Dual credit advocates say placement tests often exclude low-income students of color from dual credit programs because test scores are highly correlated with race and income. Recognizing this, some districts offered alternate paths to admission even before the pandemic. Lee College let students who achieved close-to-qualifying scores on its placement test qualify through a college admissions exam (ACT or SAT) or state high school end-of-course exam. Lorain County Community College received waivers for two technical programs at Elyria High School.

But COVID-19, which shut down testing for several months, forced more programs to experiment with new ways of admitting students. In doing so, the pandemic ushered in a “massive nationwide test of moving to multiple measures of eligibility,” says Alex Perry, coordinator of the College in High School Alliance. Some states have stuck with their new systems, he says.

And it’s not just community colleges that are stepping up. Last fall, Benedict College, a historically Black college in Columbia, South Carolina, announced that it would offer online courses – and guaranteed admission – to students in the Fresno Unified School District, while a national nonprofit said it would subsidize online courses for dual credit students at Claflin University, another South Carolina HBCU.

Meanwhile, some districts are heeding calls from the Biden administration to invest a portion of their pandemic recovery funds in expanding access to dual credit.

In Buffalo, New York, federal dollars were used to hire a dual enrollment coordinator. In Frederick County, Maryland, the money paid for textbooks and instructor training for a new course designed for English-language learners, a severely underrepresented demographic group, according to Diana Sung, the district’s dual enrollment coordinator.

Colorado, a state that has made significant progress in closing racial equity gaps in its dual credit programs, is now turning its attention to disabled students, challenging the assumption that they don’t belong in college-level courses, says Carl Einhaus, the state’s senior director of student success and P-20 alignment.

But progress across the country has been uneven, and most states still don’t demand the disaggregated data from schools that would allow them to identity underrepresented groups of students and target resources to them, says Sharmila Mann, a principal at Education Commission of the States (ECS). A recent analysis by the commission found that while close to half of states require high schools to offer a dual credit program, only six set aside scholarships for underserved students, or require colleges to do so.

For families of all income levels, the cost of dual credit courses varies widely. Roughly half of states offer free tuition in at least one dual credit program, but of the other half, a dozen cover only a portion of the cost, and another dozen provide no public funding for dual credit, according to the Community College Research Center, which analyzed the ECS data. Meanwhile, some school districts and colleges subsidize their programs for students, and some don’t. It all depends on state policy and local agreements between schools and colleges, which can make it confusing for families to sort out, Ms. Mann says.

The explosive growth of dual credit has been a godsend for the nation’s community colleges, offsetting steep enrollment declines among recent high school graduates and older adults that were magnified by the pandemic. The number of dually enrolled students in community colleges nationally shot up by 11.5% this past fall, even as overall enrollment fell, data from the National Student Clearinghouse shows.

But it’s not clear that replacing regular students with dually enrolled ones is a sustainable strategy for the struggling sector, says John Fink, a senior research associate at the Community College Research Center. That’s because two-year colleges often aren’t fully reimbursed for the cost of running the program – either by the state or by the school district. If the colleges hope to make up for their losses, Mr. Fink says, they’ll have to convince more high school students to continue their education after they graduate.

And that will only happen if community colleges put dual credit students on a course to a credential while they’re still in high school, ensuring that their credits transfer to that credential, Mr. Fink and others argue. Lee College is among those experimenting with this “pathways” approach.

“When students have a sense of purpose, they’re more likely to finish their degrees,” says Josh Wyner, executive director of the College Excellence Program at the Aspen Institute.

Rafael, who will have completed the core curriculum for Texas public colleges by the time he graduates in May, says his parents – a stay-at-home mother and a pipeline heater in the local plants – never pressured him or his siblings to pursue college. But they understood its value.

“Dad always tells me, ‘You don’t want to wake up at 5 a.m., not being with your family, struggling with the heat and cold,’” Rafael says. “He says, ‘I want you to get a good office job so you can be comfortable.’”

Rafael is still figuring out what that job will be, but he’s leaning toward accounting.

“I want to build a foundation for our family to have generational wealth,” he says. “Everything I do is for my family.”

Civics in the shadow of Capitol Hill. A letter from a D.C. high school.

Washington, D.C., students learn civics in the shadow of the Capitol, but does that matter? Most are more driven by opportunities to take responsibility for issues in their daily life, like addressing bullying or mental health.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Civics skills students at Dunbar High School up the street from Capitol Hill were practicing their citizenship responsibilities this week: casting ballots for class representatives.

“We have the power, but if we don’t use it, what’s the benefit?” says social studies teacher Shelina Warren as students drop ballots in a shoebox.

She tells her students they’ve just engaged in the same process members of the U.S. House did in picking a speaker just a mile away on Capitol Hill over the weekend – minus the circus dimensions of 15 rounds of ballots. Their votes as citizens matter because they elect the representatives who elect the speaker, she says.

Does anyone know which “House” they’re discussing, she asks.

“The White House?” offers one student.

“This is the White House,” says Ms. Warren, patiently pointing to a tabletop model. “This is the Capitol building.”

Discrimination is sophomore Asianay Butts’ favorite topic in Ms. Warren’s class, and it’s also what she worries about day to day – along with gun violence.

Nationally, civics educators know that students respond well to hands-on opportunities to make a difference in their communities.

And that’s what Ms. Warren is all about: “I’m just trying to prepare my kids ... to be productive citizens.”

Civics in the shadow of Capitol Hill. A letter from a D.C. high school.

In the wake of last week’s gridlocked rounds of voting for House speaker, sophomore civics skills students at Dunbar High School gathered for their law and justice advocacy class this week just a mile up New Jersey Avenue from the U.S. Capitol to cast their own ballots for class representatives.

“Democracy means power to the people,” says social studies teacher Shelina Warren, passing out ‘vote’ stickers as students drop their green paper ballots in a red-white-and-blue shoebox. Several girls stick them on their cheeks. “We have the power, but if we don’t use it, what’s the benefit?”

She tells her students that they’ve just engaged in the same process that members of the U.S. House did over the weekend – minus the dimensions of a national circus – and that their votes as citizens matter because they elect the representatives who elect the speaker.

Does anyone know who's third in line of succession to the presidency, she asks the dozen students fighting the fidgets of the last class of the day.

There’s a smattering of hazy no’s.

She asks, which “House” they are discussing.

“The White House?” offers one student who strikes the teen guise of disengagement facing away from the teacher while still answering every question.

“This, is the White House,” says Ms. Warren, patiently pointing to a tabletop model. “This, is the Capitol building,” she says, pointing to the model of the marble icon of democracy.

She reminds them of their field trip in the rain there last month when they toured the Capitol, not realizing they were walking the halls with freshman representatives there for their own orientation. They were more interested in the empty tombs deep below the Rotunda, once intended for Martha and George Washington.

There are more scattered no’s when she asks if students know the name Nancy Pelosi. And when she asks if Speaker Kevin McCarthy is a Republican or a Democrat, most students seem unsure. One guesses: “A Democrat?”

When Congress feels “far away”

The Capitol building is visible from some classrooms at Dunbar, yet the inner workings of the dome are far from immediate concern of students. It’s not a matter of being uninterested – Ms. Warren knows how to stoke their intellectual curiosity. When the lesson shifts to discussing restorative versus retributive justice, the students perk up and engage in a spirited debate, their voices excited and urgent.

Discrimination is Asianay Butts’ favorite topic to learn about in Ms. Warren’s class, and it’s also what she worries about day-to-day – along with gun violence.

Indeed, just hours after Speaker McCarthy was elected on Jan. 7, middle-schooler Karon Blake was shot and killed. He attended Brookland Middle School, which sends students to Dunbar. And day after day, students in D.C. public schools like Dunbar walk through metal detectors and send their backpacks through to begin their day, just as House members did after the Jan. 6 attack. But under new leadership last week, the House removed its own metal detectors outside the chamber.

Samiyah Munu, one of the class representatives, knew the votes for speaker were taking place, and although she thinks it’s important to learn about Congress, it seems “far away.” She’s more concerned about homelessness, wages, and gun violence than battles for the speakership or committee assignments. And she’s not all that hopeful Congress will solve those issues. It feels like those issues “don’t get talked about” by lawmakers, she says, “even with us living in the city of Congress.”

Nationally, civics educators are detecting that students respond well to hands-on opportunities to make a difference in their communities. Cue the growth of action civics, which calls on students to identify problems in their own sphere of experience and then hear different points of view and learn to navigate conflict with their peers, educators say.

Whether learning how a bill becomes a law or working to address bullying, action civics is “about the nuts and bolts of how students study different things and learn to improve their communities,” says Khin Mai Aung, New York executive director of civics education organization Generation Citizen.

Individual teachers, like Ms. Warren at Dunbar, have been trying to break down the wall between classroom and community for decades.

Why civics matters

Mikva Challenge is one of many organizations supporting teachers in D.C. and around the country as they implement hands-on curriculums. Ms. Warren works with Mikva’s curriculum and has shepherded students through the organization’s “soapbox challenge,” an event where students present speeches about an issue in their community to a panel of stakeholders, often including a D.C. council member. In the classroom, students choose one of the issues to pursue with an experiential civics project.

This is key, says Robyn Lingo, chief of strategy and impact at Mikva. To become engaged adult citizens, “young people need chances to practice civic skills in schools now.”

And civics education – including teaching students about government processes, activism, and developing youth governance structures within schools – has quantifiable effects. Some 90% of 300 eligible Mikva alumni voted in the 2020 presidential election – 30% higher than the national average – and 77% volunteer in their communities, says Ms. Lingo.

Ms. Warren’s action civics approach is, in a sense, extracurricular: D.C.’s social studies standards, which haven’t changed in 16 years, do not require an action civics project. But Ms. Warren was among the educators shaping a draft of new standards released in December for public comment.

In doing so, the nation’s capital is joining a number of states updating their own social studies standards. A common challenge discussed by educators examining curriculum is how to “include wide perspectives without compromising rigor,” says Noorya Hayat, a senior researcher at Tufts’ Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement.

And one thing that’s key for all teachers, regardless of location, is the distinction between historical facts like slavery that Ms. Hayat says should not be presented as debatable – and open topics, like forgiving student debt, which would be presented as open for debate.

There are many resources for civics teachers, but access comes down to funding, says Ms. Hayat – pointing to the lopsided federal spending ratio of about $50 a year per student for STEM education to just 5 cents on civics education.

Ms. Warren’s students, though, have no shortage of opportunities to practice civics skills.

Her classroom – full of photos of students participating in mock trials, quotes from activists and writers, and a “Wake me when I’m free” Tupac poster – is a visual of the push to bridge the gap between what she calls “just good pedagogy” (textbook and lecture) and “trying to get students to take some type of action.”

Her teaching revolves around showing students glimpses of the government up close (like the trip to the Capitol) and civic action they can take (like writing letters to the editor, bringing concerns and ideas to the principal, holding voter registration events, or organizing mental health support).

“I’m just trying to prepare my kids,” says Ms. Warren, so that “when they graduate and walk out of this building for the last time, they will actually be prepared to be productive citizens.”

Film

Iranian director’s poignant film champions freedom to create

In his latest work, “No Bears,” embattled Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi explores in a highly personal way the necessity of freedom of expression.

-

By Peter Rainer Contributor

Iranian director’s poignant film champions freedom to create

It’s a truism that those who are imprisoned are among the most likely to cherish freedom. I thought of this as I watched Iranian director Jafar Panahi’s “No Bears,” which was filmed several months before he was sentenced in July 2022 to six years in prison for “propaganda against the Islamic republic.” He joins the fate of so many of his country’s artists and freethinkers.

This extraordinary film, which, despite its tragic trappings, is often surprisingly playful, can be appreciated without knowing anything about Panahi or his long-term battles with the authoritarian regime. Those battles have included a prohibition since 2010 to make movies or leave Iran. But knowing about his past and present ordeals increases the movie’s poignancy. Here is a director so committed to his art that he made a film in 2011 while under house arrest and smuggled it into the Cannes Film Festival reportedly on a USB drive concealed inside a cake.

In “No Bears,” as in a number of his other films, including “3 Faces” and “This Is Not A Film,” Panahi is essentially playing a character very much like himself, with the same name. (To avoid confusion, I will refer to that character in this review within quotation marks as “Panahi.”)

When the film opens in a Turkish town bordering Iran, we are thrust into an extended streetside argument between a couple (played by Bakhtiar Panjei and Mina Kavani) desperate to flee to France. Between them, however, they have only one forged passport. In contrast to director Panahi’s usual slow-going standards, this scene is practically a thrill ride. But it is soon revealed that the two people are actors. As the story progresses, though, it becomes clear that the filmed fictional drama they are enacting parallels their own lives. They are being directed remotely by “Panahi” via video call, despite the bad Wi-Fi, from a nearby Iranian village where he has covertly taken up residence far from his native Tehran in order to make this movie.

But this hall-of-mirrors meta-dramaturgy never descends into airy artifice. Director Panahi is above all a humanist, and the film is graced with a feeling for the village and its people that goes way beyond the ethnographic. We see the women who pridefully ply him with their best traditional dishes. His young landlord, Ghanbar (Vahid Mobasheri), dotes on his famous tenant while also being somewhat suspicious of him. His neighbors are similarly both fascinated and wary. Their voyeuristic attentions parallel the authoritarian surveillance “Panahi” is hiding from.

He is recognized as a prominent person, but his city ways and somewhat gruff sense of entitlement don’t impress the village elders. The director Panahi gives their ancient traditions and superstitions a dutiful, if highly skeptical hearing. When it transpires that “Panahi,” in his wanderings about town, may have snapped an incriminating photo of illicit lovers, the elders mass against him.

They politely but firmly ask to see the photo which “Panahi” claims, probably truthfully, he did not take. In the film’s centerpiece scene, he grudgingly agrees to take an oath on the Quran, in a makeshift “Swear Room” as prescribed by custom, that he did not shoot the photo. (Ghanbar tells him not to worry, that it’s acceptable to lie, just as he admits the rumor of bears roaming the Iranian-Turkish border is a lie to keep the villagers in place.)

The film-within-the-film that “Panahi” is making, with its blighted lovers and yearning for deliverance, mimics the actions of the film itself. The elders’ dogmatic rituals and recriminations point up how both “Panahi” and the director himself are regarded as criminals by those in positions of authority.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about “No Bears” is how, despite all this heavy-duty baggage, it nevertheless averts despair. The reason for this, I think, is because the director Panahi equates filmmaking, no matter the risks, with freedom. “The hope of creating again,” he has written, “is a reason for existence.”

Peter Rainer is the Monitor’s film critic. “No Bears” is unrated. It is available in select theaters.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The humility of contrition opens a healing path in Indonesia

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A quarter century has passed since Indonesia ended the strongman rule of General Suharto – although not an authoritarian mindset left behind. On Wednesday, the Southeast Asian country began a shift to liberate itself from the burden of past atrocities.

President Joko Widodo, elected twice in the world’s third largest democracy, expressed deep regret for 12 of the most egregious cases of mass human rights violations over the past six decades. While not a full-throated apology, his official contrition on behalf of the state also came with a promise to make amends and pursue both reconciliation and justice.

The president’s attempts to reopen the past may reflect a reaction to last year’s full apology by Indonesia’s former colonial master, the Netherlands, for its violence during the 1945-1949 struggle for Indonesian independence.

Humility can beget humility in the healing of nations. The first step is shining a light on the errors committed, which can then bring about a measure of justice and mercy, not to mention rule of law and civic equality. Only then, as Mr. Widodo suggests, can massacres be prevented.

The humility of contrition opens a healing path in Indonesia

A quarter century has passed since the sprawling archipelago nation of Indonesia ended the strongman rule of General Suharto – although not an authoritarian mindset left behind among the governing elite. On Wednesday, the Southeast Asian country began an important shift to liberate itself from the burden of past atrocities, even those committed by governments during the post-Suharto era.

President Joko Widodo, elected twice in the world’s third largest democracy, expressed deep regret for 12 of the most egregious cases of mass human rights violations over the past six decades. While not a full-throated apology, his official contrition on behalf of the state also came with a promise to make amends and pursue both reconciliation and justice.

“I have deep sympathy and empathy for the victims and victims’ families,” he said after receiving a report from a team set up last year to review recent Indonesian history. “Therefore, first of all, the government and I are trying to restore the victims’ rights in a fair and wise manner without negating the judicial settlement. Second, the government and I hope that serious human rights violations will no longer occur in Indonesia in the future.”

That last remark reflects the difficulty for Indonesia’s elected leaders in confronting security forces that see themselves as guardians of national unity in a country that has coped with separatist insurgencies, from Aceh on the island of Sumatra to the easternmost province of Papua.

Indonesia has also not come to grips with its most violent period – the anti-communist, anti-Chinese massacres in 1965-66 when Suharto took control and reigned for 32 years. (That dark period was made famous 11 years ago in the documentary film “The Act of Killing.”) The world’s fifth most populous country also needs justice and reconciliation for the mass killing of pro-democracy activists in 1998 who helped force Suharto to step down.

The president’s attempts to reopen the past may reflect a reaction to last year’s full apology by Indonesia’s former colonial master, the Netherlands, for its violence during the 1945-1949 struggle for Indonesian independence. The Dutch also offered compensation to the children of executed Indonesians, a step that Indonesia might follow for victims of its own past abuses.

Humility can beget humility in the healing of nations. The first step is shining a light on the errors committed, which can then bring about a measure of justice and mercy, not to mention rule of law and civic equality. Only then, as Mr. Widodo suggests, can massacres be prevented.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayer when a player goes down

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Lauren Crandall

In the face of accident or injury – on the playing field or otherwise – we can turn to God as a reliable help.

Prayer when a player goes down

My family is full of devout sports fans. Football, basketball, soccer, hockey, track, volleyball, rowing, whatever – we love it all. We’re drawn to the spirit of competition and the grit we see when an underdog wins, an athlete seems to defy the odds, or a great play turns a ho-hum matchup into a real contest.

However, injuries – some of them violent and serious – can seem to be a regular part of sporting events. I’ve found that prayer is a valuable response in such situations.

When I was growing up, if an athlete went down injured, my mom would encourage us to pray. I’d learned in the Christian Science Sunday School that everyone – including athletes – is a child of God, Spirit, and therefore expresses spiritual qualities such as grace and strength. Our prayers would affirm that these qualities came directly from the divine source of unlimited power and goodness – God. This meant that we’re all divinely empowered to express such qualities – without interruption. And we were encouraged by the many instances we witnessed of players getting up and rejoining the game quickly.

Mary Baker Eddy, who founded this news organization, puts it simply: “Whatever is governed by God, is never for an instant deprived of the light and might of intelligence and Life” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 215). This tells us that the omnipotent God, Life, is always present and active, and can’t leave any of us, even for a split second.

While the Apostle Paul, a follower of Jesus, may not have been an athlete, he did use running and racing as metaphors for his spiritual messages. And the Bible’s book of Acts tells us of a time when Paul found himself in an arena of sorts, and an audience member “went down,” so to speak (see Acts 20:7-12).

It was during one of his missionary visits. Paul “continued his speech until midnight,” and Eutychus, a young man in the audience, had maybe had a long day too. He fell asleep and tumbled out of a third-story window. The Bible tells us he was “taken up dead.”

The Bible doesn’t say, but it’s not hard to imagine it might have been a frightening, chaotic environment. But Paul remains calm and settles the scene. He embraces Eutychus and says something remarkable: “Trouble not yourselves; for his life is in him.” And indeed, the audience finds that Eutychus is alive.

The account ends with the audience’s response to this turn of events: They “were not a little comforted” – or, as the New Living Translation puts it, “everyone was greatly relieved.” Haven’t we all felt similarly comforted when someone gets up and returns to the playing field, whether literally or figuratively!

This account illustrates our true, permanent status as loved, safe, intact, never fallen. God’s spiritual offspring can never not express the life and love of our divine source, even for an instant. This spiritual reality is a powerful foundation for prayer that heals.

I experienced this when my daughter fell off a horse in a crowded warm-up ring before a horse show. The horse had stumbled hard, and my daughter flew off, landing hard headfirst.

I prayed instantly to know that the qualities of God she was expressing as a rider couldn’t be stopped or stalled. It came to me in that split second that although I couldn’t physically get to my daughter immediately, I could trust that her divine Mother, God, was governing and keeping her safe. I felt calm and panic-free.

In the next instant, she jumped up off the ground, turned to me with a big smile, and gave me two thumbs up. She dusted herself off, re-mounted her horse, and entered the show ring for her class. I found out after she returned from the ring (with a second-place ribbon!) that she’d been completely unhurt and unruffled by her fall. This was five years ago, and in the extensive riding she’s done since, she’s had no further falls or injuries.

When we learn of someone going down, whether on the sports field or in life more generally – whether or not we know them or are present in person – we can affirm the spiritual qualities that all of us are created by God to express, and know that there’s never an instant when anyone is outside the care of the all-powerful God. And this opens the door for healing.

A message of love

Greeting the sun

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at how California’s extreme drought, wildfires, and now storms are combining.