- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Israeli streets swell with urgent cry: ‘Democracy!’

- In politics, there are no second acts. Enter Kari Lake.

- Amid toxic risks after train derailment, Ohio town seeks answers

- ‘Buoyed by their resilience’: Reporting on life during wartime

- Theater vérité: How ‘The Jungle’ re-creates a refugee encampment

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

News outlets rally behind jailed Kashmiri journalist Fahad Shah

A full year has passed since Fahad Shah, editor of The Kashmir Walla newspaper and an internationally respected reporter with whom we have worked, was arrested on Feb. 4, 2022, in Kashmir for publishing “anti-national content.”

The Kashmir Walla, which Mr. Shah founded, elevates the voices of everyday people and stands fast against unjust laws with honest reporting. But Mr. Shah has paid a heavy price for that work. He has been granted bail repeatedly, only to be immediately rearrested. He continues to be held in a jail in Jammu, far from family and friends, under the anti-terror Unlawful Activities Prevention Act. He is facing life imprisonment if convicted.

Mr. Shah’s case is a sharp reminder of the need to strengthen free voices as efforts to shut them down intensify daily around the globe. His release is particularly important to the cause of free press in Kashmir.

We, the undersigned, call on authorities to release Mr. Shah immediately and to respect his standing as an independent journalist.

Mark Sappenfield, Editor, The Christian Science Monitor

Ravi Agrawal, Editor-in-Chief, Foreign Policy

Erica Berenstein, Executive Producer of News and Documentary, Insider

Dave Besseling, Longreads Editor, South China Morning Post

D. D. Guttenplan, Editor, The Nation

Daniel Kurtz-Phelan, Editor, Foreign Affairs

Boyoung Lim, Senior Editor, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting

Katharine Viner, Editor-in-Chief, The Guardian

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Israeli streets swell with urgent cry: ‘Democracy!’

The demonstrations in Israel against proposed legislation curtailing the powers of the judiciary are intensifying, spurring warnings of a national emergency and disbelief among protesters that democratic values are under threat.

-

By Danna Harman Contributor

In recent weeks, the battle cry of “Democracy” has echoed across a broadening spectrum of Israeli society with increasing urgency. It’s a response to proposed legislation by the hard-right coalition that would give the government more power to select judges and allow it to overrule Supreme Court rulings with a simple parliamentary majority.

Hundreds of thousands of people – from members of the ultra-Orthodox community to army veterans to high-tech executives – are joining together, making comparisons to democratic backsliding in Hungary and Poland.

“People look stunned at the situation they are in,” says Yotam Margalit, a senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute. “We never thought the basic fundamentals of our country would be threatened in such a way in our lifetimes.”

Shikma Bressler, founder of a group opposed to Benjamin Netanyahu’s tenure as prime minister while facing corruption charges, says the proposal’s implications are chilling.

“They are knowingly dealing with a nation of a people who grew up on stories of how bad things can get when a dictatorship takes hold,” says Dr. Bressler. “This is a nation of people who ask themselves all the time: ‘What would I have done if I had lived in those days?’ ... Well. Now is the time to answer that question.”

Israeli streets swell with urgent cry: ‘Democracy!’

As protests go, there’s a difference between chants, over the years, of “Hey, hey, ho, ho, Bibi has got to go,” and repeated shouts of “Democracy!”

This one word – pronounced “De-mo-crat-ya” in Hebrew – is the protest slogan of the moment.

In recent weeks, it has echoed across Israel with increasing urgency, anxiety, and frequency. And it is repeated – often accompanied by a steady beat of drums – by citizens from a widening swath of the political spectrum.

The groundswell is a reaction to proposed legislation by the new hard-right religious-nationalist coalition led by “Bibi,” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, which would give the government more power to select judges and allow it to overrule Supreme Court rulings with a simple majority in parliament.

The government calls the legislation a needed reform of an overpowerful judiciary. Others see it as a way to weaken the Supreme Court and attorney general – and hand the government unchecked power.

Hundreds of thousands of people – from members of the ultra-Orthodox community to army veterans to high-tech executives – join together week after week, making comparisons to democratic backsliding in Hungary and Poland.

“Look around at the demonstrations,” suggests Yotam Margalit, a Tel Aviv University political science professor and senior fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute. “People look stunned at the situation they are in. Something truly unprecedented is happening.”

Broadening opposition

The rhetoric is sharpening, with mutual accusations of incitement and attempted coups. Sunday night, President Isaac Herzog stepped out of his normally ceremonial role to issue a televised warning. Conceding the need for some judicial reform, he asked all sides to work on it together to avoid a “constitutional collapse” and possible violence. “This powder keg is about to explode,” he said. “This is an emergency.”

Over the last 75 years, Israelis – argumentative, opinionated, polarized – have voiced many frustrations and demands: “Stop the occupation!” “This is not our war!” “Traitors!” Even, in the lead-up to the 1995 assassination of Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, “Nazis!”

“Sure, one side or another in this country has almost always disagreed with the policies of those in power,” says Professor Margalit. “But we never thought the basic fundamentals of our country would be threatened in such a way in our lifetimes. And yet it’s happening, rapidly.”

Weekly Saturday night protests in Israel’s major cities have morphed into an almost daily ritual, with activities outside the homes of coalition members and in front of the Knesset and Supreme Court. “Save our Democracy” petitions are being passed around, WhatsApp groups are proliferating, and tempers flaring.

Protests reached a crescendo Monday when the Knesset’s Constitution, Law, and Justice Committee held its first vote on the proposed judicial changes – prompting Israelis around the country to strike and travel en masse to Jerusalem with their flags and chants.

Unsurprisingly, almost the entire legal establishment has come out against the proposed changes.

Perhaps even more critically, so have many of Israel’s top financial and economic leaders, from the governor of the Bank of Israel to CEOs of the country’s major banks and leaders of Israel’s vaunted high-tech industry.

Jewish communities across the world are taking out full-page ads in the Israeli press to express support for the anti-bill camp. Foreign leaders, typically careful about commenting on internal Israeli affairs, have offered veiled rebukes of the plan too.

“The genius of American democracy and Israeli democracy is that they are both built on strong institutions, on checks and balances, on an independent judiciary,” U.S. President Joe Biden said in a statement to The New York Times.

“What would I have done?”

The Black Flag movement, which came to prominence in 2020-21 to protest Mr. Netanyahu’s continued tenure as prime minister while facing corruption charges in court, has returned as part of this broader protest movement.

Mr. Netanyahu has everything to gain from weakening and controlling the courts, says the movement’s founder, Shikma Bressler, a physicist at the Weizmann Institute of Science. But the larger implications of the proposed judicial changes are far more chilling than the promotion of one man’s narrow self-interest, she says.

“They are knowingly dealing with a nation of a people who grew up on stories of how bad things can get when a dictatorship takes hold,” says Dr. Bressler, excusing herself for the Holocaust comparison, and then immediately taking it up again. “This is a nation of people who ask themselves all the time: ‘What would I have done if I had lived in those days? What would I have done when I understood minorities were not going to be protected anymore?’ Well. Now is the time to answer that question.”

On Monday, Dr. Bressler was out in the plaza in front of the Knesset, together with scores of thousands of other protesters.

“Hundreds of thousands did not go to work or school today,” she says. “That’s a statement. And we are willing to take more aggressive steps and shut down the economy.”

It’s not only the number of protesters that is critical to organizers, but also their diversity, though the government and its supporters accuse the current wave of protesters of being homogeneously white, privileged, and leftist.

Mr. Netanyahu calls them “anarchists.”

“We are patriots”

“We resent being dismissed this way,” says Noga Halevi, spokeswoman for a protest group called Brothers in Arms, made up of alumni of Israel’s most elite commando unit, Sayeret Matkal, and other elite units.

“We are patriots. We are Zionists who care and love this country. We have served it and we will keep on serving. In fact, we feel that this protest is our best way of serving now.”

“Most of us in this group are not typical activists,” says one member, speaking off the record because he still is in active service. “Also, many of us are on the right side of spectrum! I am not here against Bibi. I want the government to succeed! I even believe there needs to be judicial reform. But I know reform and I know danger. This is danger.”

While these soldiers urge legal and peaceful means of protest, some politicians are less reserved in their choice of words.

“We now must get to the next stage, the stage of war, and war is not waged through speeches. War is waged in a face-to-face battle, head-to-head and hand-to-hand, and that is bound to happen here,” former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert – once a member of Mr. Netanyahu’s Likud party – said in a TV interview this week. Mr. Netanyahu and his party announced they were filing a police complaint against Mr. Olmert for incitement.

Tel Aviv Mayor Ron Huldai, also facing a similar complaint, warned demonstrators on Monday that “democratic countries such as ours can become dictatorships. But dictatorships can only return to be democracies through bloodshed.”

A crisis scenario

How effective, then, are all these demonstrations, warnings, and threats?

Professor Margalit says one likely scenario is a clash between branches of government, the judiciary and the executive. If the courts ruled against one of the new laws, and the government chose to ignore the ruling, that would precipitate a serious crisis.

In such a standoff, the numbers and diversity of Israelis standing up to be counted lend legitimacy to the judiciary, argues Professor Margalit. “The Supreme Court needs to have not only legal justifications in this battle, but also a moral justification,” he says. “Having a clear majority of the country behind them could strengthen their resolve.”

For a few days after President Herzog made his appeal, the ruling coalition seemed open to his offer to broker a compromise. So far, however, it is rejecting the opposition’s insistence that, in order to start such negotiations, the government needs to pause the race to get the bills passed.

Justice Minister Yariv Levin, a close ally of Mr. Netanyahu, said the judicial bills will be tabled in the Knesset, as planned, for the first of three readings, this coming Monday.

Leaders of the protest movement immediately countered that they would be there too.

A deeper look

In politics, there are no second acts. Enter Kari Lake.

One of the clearest messages from the 2022 elections was voters’ rejection of politicians who echoed former President Trump’s claims of fraud. But could Kari Lake’s charismatic brand of election denialism shape not only the future of Trumpism but the 2024 race?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 17 Min. )

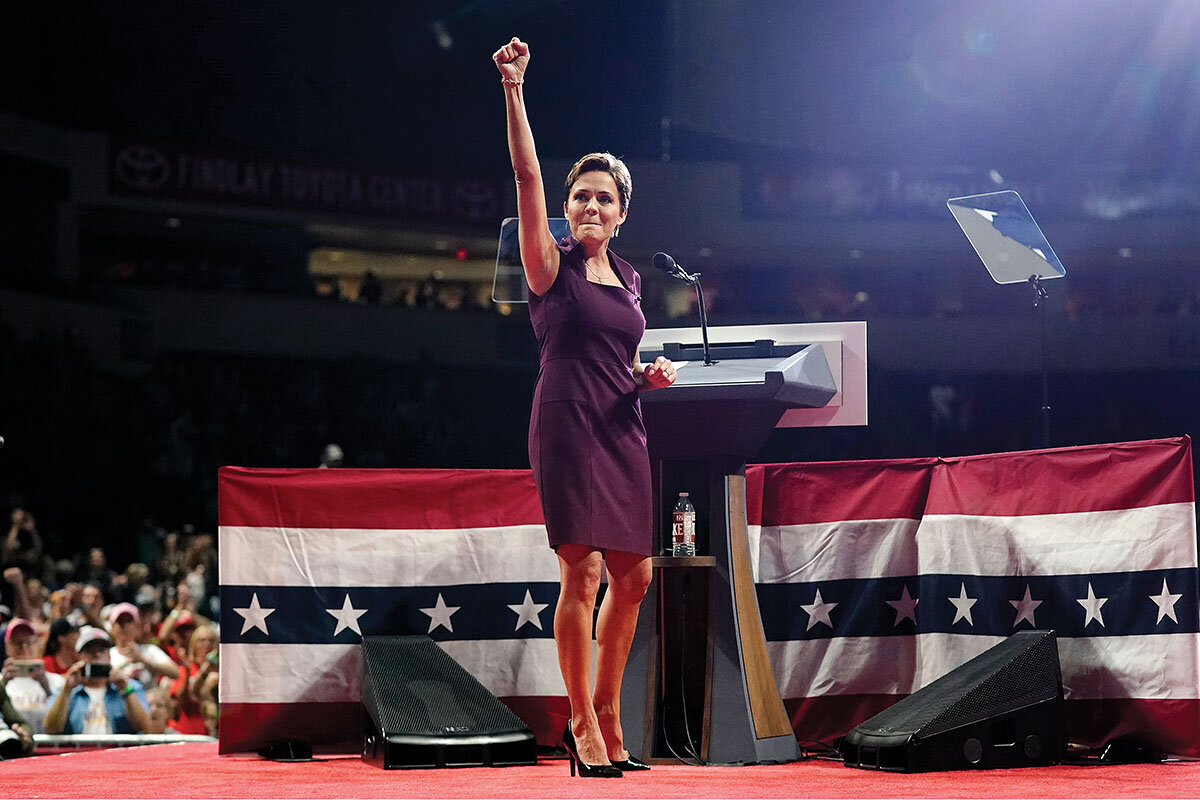

A prairie wind cuts the winter sun outside the faux-industrial space where some 150 people have shown up to see Kari Lake outside Des Moines. It’s standing room only below the exposed ducts and metal girders, and the warmup playlist could have been borrowed from a Trump rally: “Tiny Dancer,” “Gloria,” and – perhaps fittingly for a candidate who lost her bid for Arizona governor but hasn’t conceded – “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough.”

Ms. Lake, a TV anchor-turned-MAGA warrior widely heralded as one of 2022’s rising political stars, refuses to see the writing on the wall. She wants to bulldoze that wall. And so, she’s still out there campaigning. Meeting with Republican senators. Blitzing right-wing media. Making an eyebrow-raising trip to Iowa, an early presidential voting state.

That chutzpah now has a certain pathos to it. But Ms. Lake’s sheer refusal to accept defeat could impact more than her own political trajectory. In this pivotal period of transition for the Republican Party – with Donald Trump seemingly diminished but trying to reassert his hold – Ms. Lake’s charismatic brand of election denialism could shape not only the future of the MAGA movement but also the 2024 Senate map and even the presidential race.

“Kari has never quit campaign mode,” says Tyler Montague, a GOP consultant. “She’s the most popular figure among the far right in Arizona now. So what she does next matters.”

In politics, there are no second acts. Enter Kari Lake.

Among Arizona Republicans, Kari Lake needs little introduction. So, at a recent state party meeting, the outgoing chairwoman, Kelli Ward, keeps it simple.

“Our real governor!” she declares.

Ms. Lake, wearing a red frilled blouse, lavender-gray pants, and black stilettos, takes the stage at a Phoenix megachurch to thunderous applause and cheers. She briefly basks in the acclaim before launching into a quick-fire speech about election fraud, former President Donald Trump – she just got off the phone with him, and he “loves Arizona” – and the rally she’s holding the next day where she will talk about, once again, election fraud.

“People are watching what’s happening in Arizona,” she says. “They saw it in broad daylight as our elections were stolen right in front of our eyes.”

Ms. Lake, who lost the governorship by a whisker to Democrat Katie Hobbs in November, says she’s fighting in court to reverse the results and get to work fixing “our corrupt elections.”

That court case – which she already lost and is pursuing on appeal – is “going really, really well,” she tells the 1,000-plus crowd. On Feb. 16, the Arizona Court of Appeals also ruled against Ms. Lake, declining to force out Governor Hobbs and declare a new election. Ms. Lake immediately vowed to take her case to Arizona’s Supreme Court.

Nearly three months after her defeat, Ms. Lake is still at the first stage of grief: denial. There’s also anger, the second stage, which she will uncork at the rally, but today it’s all denial. Denial of Arizona’s election procedures, vote tallies, and official audits. Denial that the Trump-endorsed slate of candidates she led in November lost. Denial of the legitimacy of Ms. Hobbs and other elected Democrats, whom she calls “frauds who took over our state government.”

Less explicitly stated, but just as clear, is her denial of the fact that many leaders in her own party are eager to turn the page on candidates like her. One of the clearest messages to emerge from the 2022 elections was voters’ rejection of politicians who echoed former President Donald Trump’s false claims of electoral fraud. Many moderate and independent voters saw the GOP as “sort of nasty and tended towards chaos,” Sen. Mitch McConnell said afterward. The solution, the Republican Senate leader added pointedly, will be to run “quality candidates” next time.

But Ms. Lake, a TV anchor-turned-MAGA warrior who had been widely heralded as one of 2022’s rising political stars, refuses to see the writing on the wall. She wants to bulldoze that wall. And so, some 100 days after the election, she’s still out there campaigning. Meeting with Republican senators in Washington. Blitzing right-wing media. Even making an eyebrow-raising trip to Iowa, an early presidential voting state.

That chutzpah, once seen as a measure of strength, now has a certain pathos to it. But Ms. Lake’s sheer refusal to accept defeat could impact more than her own political trajectory. In this pivotal period of transition for the Republican Party – with Mr. Trump seemingly diminished but trying to reassert his hold – Ms. Lake’s charismatic brand of election denialism could shape not only the future of the MAGA movement but also the 2024 Senate map and even the presidential race.

“Kari has never quit campaign mode,” says Tyler Montague, a GOP consultant who opposed her candidacy. “She’s the most popular figure among the far right in Arizona now. So what she does next matters.”

Since November, Ms. Lake’s nonstop attacks on GOP election supervisors she calls “Judas Republicans” have netted her millions of dollars from donors across the country and fed a fantasy among her base that, any day now, she will turf out Arizona’s actual governor. Because what possible explanation, besides cheating, could explain what happened after Ms. Lake had been leading in all the polls?

“I was knocking on doors. I know what I saw. It’s inexplicable,” says Patty Porter, a GOP state committee member, who believes the vote was rigged.

In many ways, it’s a replay of the aftermath of the Trump 2020 campaign. For candidates challenging elections, there’s now a familiar script: Relentlessly highlight certain data points, warn that democracy is under attack, and accuse the media of complicitly turning a blind eye. Ms. Lake’s still-active war room sends out regular tweets wondering, for example, how Democrats could have won four statewide offices in Arizona while voters also elected Republican congressional candidates by double digits overall (answer: because some of those GOP candidates were running unopposed). Through a spokesperson, Ms. Lake turned down requests for an interview with the Monitor.

Some who worked to elect Ms. Lake wonder if she truly believes everything she says. Yet others insist this is the true Kari Lake – a MAGA devotee whose own foray into politics was spurred by her genuine conviction that the 2020 election had been stolen from Mr. Trump. “From the first time I met her [her belief in election fraud] was very clear to me,” says a former campaign staffer. “I knew if she lost this is what was going to happen.”

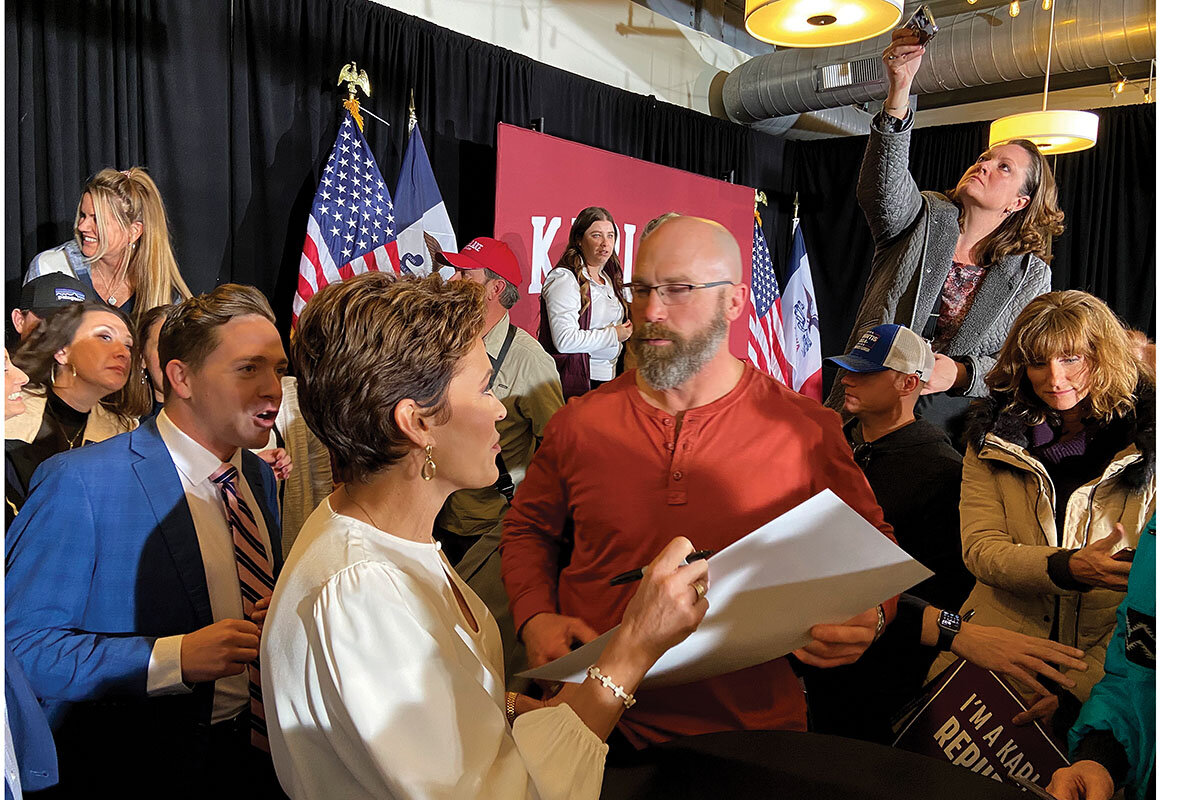

Trumpism’s “leading lady”

At the back of a brightly lit event space outside Des Moines, Myrna Garcia eyes a crowd of people pressing toward a stage flanked by U.S. and Iowa flags, with Kari Lake’s name emblazoned in the center. Music echoes off brick walls as volunteers greet guests and hand out flyers.

Like nearly everyone in the room, Ms. Garcia is full of enthusiasm about Ms. Lake and her political future. “She’s got a riveting personality,” says the home caregiver. “She’s young. She’s vibrant. She’s aggressive.”

“She’s the most outstanding American citizen I know,” agrees Steve Allison, an engineer. “I could see her going all the way to the White House.”

That a failed gubernatorial candidate from a state some 1,300 miles away is packing a hall full of Iowans in a non-election year is testament to Ms. Lake’s appeal. Among a certain segment of the GOP base, who have watched her do hit after hit on conservative media, she’s second only to Donald Trump. Many here muse about the possibility of a Trump-Lake ticket.

In the mainstream press, no Republican in the 2022 cycle was treated to as much hype as Ms. Lake. She was profiled, endlessly, as the “new face of the MAGA right,” and Trumpism’s “leading lady.”

As a candidate, she could make an instant connection with people, says a former campaign staffer. “People just thrived off of it. She had the ability to make you feel like she was talking to every person in the room.” Even associates who believe her tactical missteps – feuding with fellow Republicans, alienating traditional donors, muddling her policy agenda – handed a winnable election to a Democrat remain in thrall to her political skills and stage presence.

“She was the most talented candidate I’ve ever seen. It’s not even close,” says another former staffer.

When Ms. Hobbs, Arizona’s soft-spoken then-secretary of state, refused to debate her – saying Ms. Lake would turn the forum into a “circus” – even some Democrats began criticizing their own candidate as weak.

All of which made the fall, when it came, that much more jarring.

Ms. Lake’s narrow loss – by 17,000 votes out of 2.5 million cast – was to many a surprise. But the overall voting patterns were not, says Benny White, a Republican data analyst. In Maricopa County, where 6 in 10 Arizona voters live, enough Republicans and independents rejected Ms. Lake and other far-right candidates who denied the legitimacy of the 2020 election to tip close races to Democrats. “They were predictably unelectable,” he says.

To wit: 33,794 voters in Maricopa who chose GOP candidates down ballot also picked Ms. Hobbs as governor. On the flip side, 8,541 Democrats chose Ms. Lake, according to Mr. White’s analysis of voting records. That deficit – nearly 25,000 crossover votes, mostly in affluent suburbs – was enough to sink her chances in the county that typically decides elections in Arizona.

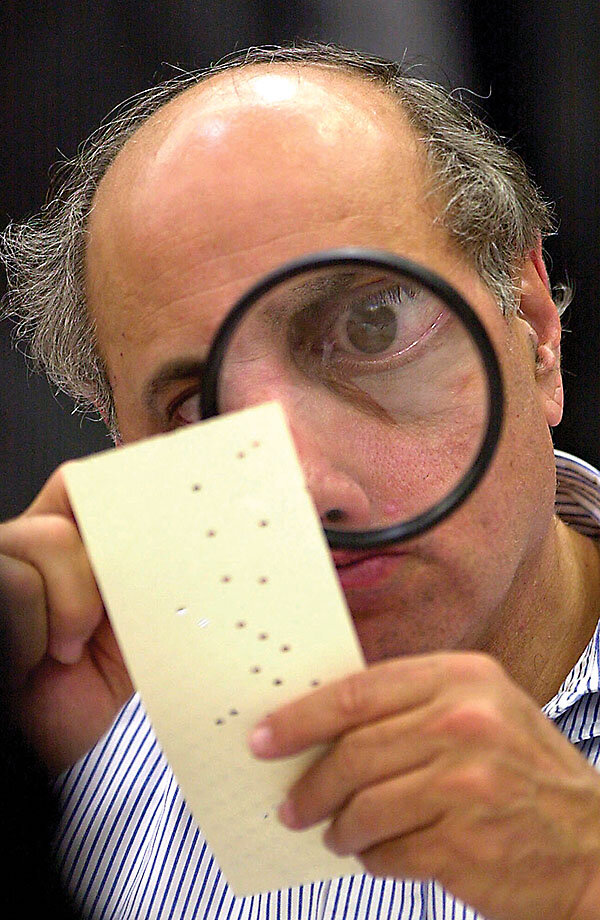

Maricopa had had ballot printing problems on Election Day that disrupted the process and caused longer wait times. A report later issued by the county concluded that fewer than 1% of ballots were affected, and “no voter was disenfranchised” by the problem. But many of Ms. Lake’s supporters immediately cried foul.

After Ms. Hobbs was projected the winner, Ms. Lake went briefly and uncharacteristically silent, simply tweeting: “Americans know BS when they see it.” Shortly thereafter, she announced she was assembling a legal team to challenge the results.

Her own campaign counsel did not join the lawsuit. Instead, Ms. Lake has been represented by a divorce lawyer who had represented the now defunct Cyber Ninjas firm in their widely discredited “audit” of Arizona’s 2020 election.

On Dec. 24, an Arizona court dismissed Ms. Lake’s lawsuit to overturn the election after holding two days of hearings, during which none of her witnesses could testify to any acts of intentional misconduct by election officials in Maricopa County.

“The Court cannot accept speculation or conjecture in place of clear and convincing evidence,” wrote Judge Peter Thompson.

The court had agreed to the hearings after dismissing eight related claims as meritless. Ms. Lake is appealing both the verdict and the dismissal of her other claims.

A sharp right turn

If election fraud and a corrupt media are the main animating passions of Kari Lake the candidate, to some former friends and colleagues, it’s a baffling departure from the woman and journalist they once knew.

Ms. Lake, who grew up in Iowa as the youngest of nine children, moved to Phoenix in 1994 to work as a TV weather reporter. Five years later, she landed a job as an evening news anchor on Channel 10, a Fox affiliate.

Married with two children, Ms. Lake could be demanding but also warm and supportive, former colleagues have said. (Most current employees are legally barred from talking about her.) Few saw a political edge to her.

“She was a super normal person,” says Marlene Galan-Woods, a former news anchor in Phoenix whose late husband, former Republican Attorney General Grant Woods, negotiated Ms. Lake’s contracts.

Ms. Lake has said she voted for Barack Obama in 2008. In 2016, though, she began to post pro-Trump messages on social media and became more outspoken in support of conservative causes, which irked station managers who insisted on neutrality from anchors. Then, in 2019, Ms. Lake was caught on a hot mic using profanity to put down a Phoenix alternative weekly newspaper.

She left that day, hired an attorney to handle the fallout, and didn’t come back for a month, says Diana Pike, Channel 10’s human resources director. Staff had to cancel vacations to cover for her. She never apologized for what happened after her return, says Ms. Pike, who has since retired.

“People were so mad at her. She came back in the newsroom like a conquering hero, and they just ignored her. That’s how she treated people,” she says.

The tensions grew after the 2020 election, when Arizona was convulsed by Trump protesters blaming fraud for his loss, allegations amplified online by Ms. Lake. She left the station in March 2021. Ms. Lake claims she quit in disgust with the news media. Ms. Pike calls it a mutual separation.

Three months later, Ms. Lake announced her run for governor.

She faced well-funded opponents in the Republican primary. By then, she had built a national profile as a 2020 election denier and a crowd-drawing celebrity, which earned her Mr. Trump’s endorsement. She held fundraisers at Mar-a-Lago and spoke regularly to the former president, fueling talk of Ms. Lake as a potential vice presidential pick.

After she won the primary, Republican strategists saw a clear path to consolidate the vote and shut out Ms. Hobbs, the Democratic nominee. Everything seemed to be going Ms. Lake’s way.

“Money wasn’t the issue that it was in the primary. Money was rolling in from across the country,” says Thomas Van Flein, the chief of staff to GOP Rep. Paul Gosar, who took a leave to advise the campaign.

But Ms. Lake didn’t tack to the center, or even the center-right. Instead, she stuck to right-wing cultural grievances and “election integrity,” and largely ignored critical local issues like water and education. She put Caroline Wren, a former Trump fundraiser who was a “VIP Advisor” to the Jan. 6, 2021, rally that preceded the Capitol riot, in charge of her campaign. She appeared alongside former Trump strategist Steve Bannon and other MAGA firebrands, mocking “McCain Republicans” in Arizona as insufficiently conservative. She even vacuumed a red carpet for Mr. Trump to stand on when he visited.

It was all “Trump, Trump, Trump,” recalls a former campaign consultant. Ms. Lake and her inner circle, according to this strategist, had begun to treat Arizona as the launchpad to a presidential ticket, even as the governor’s race tightened. “She didn’t want to be governor. She wanted to be Trump’s running mate,” says the consultant.

These distractions, along with Ms. Lake’s unapologetically aggressive style, helped turn a winnable race into a toss-up, says this consultant. “It was ours to lose. We did it. Well, she [Ms. Lake] did it.”

Attacks on election officials

Inside a suburban golf club, Kari Lake stares out into a sea of faces. More than a hundred boisterous supporters are crammed into a windowless room, with many more waiting outside. Some hold printed signs that read “Save Arizona” and “Karizona.” It’s 95 degrees Fahrenheit inside the room.

“I didn’t realize everybody would show up tonight,” she says brightly. “This is great. We have the people with us. But they have the corrupt election officials with them. That’s how they win.”

Today, Ms. Lake goes one better with her Trump connection. “We have the president on the phone,” she crows, holding up an iPhone. “President Trump, you’re not going to believe this crowd. Everyone in Arizona cares about election integrity.”

As the crowd cheers, Mr. Trump’s voice can be heard through the phone, repeating Ms. Lake’s allegations that “the machines” broke on Election Day in “Republican areas.” She alleges this was a deliberate ploy to depress her vote. The court found, however, that the malfunctions didn’t stop anyone from voting, nor did the errors disproportionately affect GOP-leaning areas, though Republicans were more likely to have been affected overall because they were less likely to vote by mail.

Ms. Lake says the only remedy is a new election, calling Ms. Hobbs a “squatter” in the governor’s office. “Don’t get too comfortable, sweetie,” she says, with a steely grin.

Her biggest targets, however, are the GOP officials in Maricopa County who oversaw the election.

She displays a photo of Stephen Richer, the Maricopa County recorder, and Bill Gates, a county supervisor. “These clowns trampled on the sacred right to vote,” she thunders as the crowd chants, “Lock them up!”

Both men have received multiple death threats, and Mr. Gates and his family had to move out of their home during the election. A man in Missouri was charged in federal court last August after making death threats to Mr. Richer. In July, the FBI arrested a Massachusetts man who made bomb threats against Ms. Hobbs, who as secretary of state certified Joe Biden’s victory in Arizona in 2020.

During her campaign, Ms. Lake also made Arizona’s media a regular foil. She called out reporters by name, criticizing their coverage, and told a news conference in November that if elected she would be the media’s “worst freaking nightmare.”

Tonight, she accuses reporters in the room of ignoring her evidence of fraud and urges them to tell the truth. “Tell the truth! Tell the truth!” her supporters chant.

“I’m tempted to take it and slap them in the face with it,” she says. “There’s a reason that we rope the media off, and it’s not for my protection.” The crowd erupts again.

Last October, 60 former media professionals in Arizona signed a joint statement urging political candidates – none by name – to stop threatening the media, writing “bullying reporters for political gain is unacceptable and unpatriotic.”

Ms. Galan-Woods, the former news anchor, was one of them. She believes Ms. Lake’s rhetoric could incite violence. “It’s reprehensible,” says Ms. Galan-Woods, a Democrat who is considering a run for Congress. “I think she knows better.”

What comes next

Few politicians in U.S. history have suffered a more excruciating loss than Al Gore in 2000. Denied a full recount by the Supreme Court, he lost Florida – and with it, the election – to George W. Bush by a margin of 537 votes, amid a spectacle of “hanging chads” and a confusing “butterfly” ballot that caused some 2,000 Democratic retirees to accidentally vote for conservative Pat Buchanan.

The crisis ended when Mr. Gore gave a gracious and widely praised speech in which he urged the country to come together. After that, he followed the generally approved next steps for a losing candidate. He grew a beard and took a six-week trip to Europe. He avoided directly criticizing his opponent, then in the White House. In time, he turned his painful defeat into a laugh line. “I am Al Gore, and I used to be the next president of the United States of America,” he would say.

The final stage of grief – after denial, anger, bargaining, and depression – is acceptance. For losing candidates like Ms. Lake, say many strategists, accepting defeat is necessary in order to properly assess what went wrong and mount a better campaign next time.

Yet near-miss candidates often discover that lightning rarely strikes twice. Onetime Democratic superstar Stacy Abrams, who herself cried foul after narrowly losing the race for Georgia governor in 2018, took a second crack at it last year but never caught fire. In Texas, Beto O’Rourke was never able to recapture the momentum from his narrow loss to Sen. Ted Cruz, mounting failed presidential and gubernatorial campaigns.

In that sense, there may be a certain logic to Ms. Lake’s steadfast refusal to concede. Her ongoing crusade has also become a money-generator, just as Mr. Trump turned defeat into gold after 2020. Ms. Lake has raised $2.5 million since the election, of which less than 10% has been spent directly on her litigation efforts. Most donations have come from out of state.

This money machine creates more incentives for Ms. Lake to keep making her case, says Kathy Petsas, a GOP activist who calls herself a McCain Republican. “She has celebrity derangement syndrome. There’s a constant need for attention,” she says.

Some associates say Ms. Lake could still pivot and move on: Concede the election and focus on a conservative policy agenda, while continuing to call for greater accountability in election administration. There is plenty of work to do. Maricopa officials have yet to get to the bottom of their equipment failures and have appointed a former state supreme court judge to investigate.

Others see little chance of that happening. Some even express unease at the idea of Ms. Lake potentially holding public office in the future. “I’m glad she lost,” says a former staffer. If she winds up running again, “I’d work for free against her, that’s how I feel about her being in leadership.”

That opportunity may come as soon as next year. Ms. Lake appears to be eyeing a run for Arizona’s Senate seat currently held by Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat-turned-independent. Ms. Lake’s been courting national Republicans and has kept on much of her campaign team under Ms. Wren.

Rep. Ruben Gallego has already announced he’ll seek the Democratic nomination, setting up a potential three-way race. Should that happen, a split Democratic vote could pave the way for a Republican win. But Senator Sinema may also conclude by next year that she has no path to victory as an independent.

Under that scenario, Arizona Republicans will need a candidate who can appeal beyond the base. That didn’t happen in 2022, says Karrin Taylor Robson, a businesswoman who lost to Ms. Lake in the gubernatorial primary and is already being mentioned as a possible Senate candidate in 2024.

Politics is all about addition, not subtraction, and that means not alienating members of your own party, Ms. Taylor Robson writes in an email. “When the party gets tired of losing general elections, it will start to nominate candidates that are able to build winning coalitions.”

Mr. White, the data analyst, has come to the same conclusion: MAGA candidates like Ms. Lake probably can’t win a majority in a state where independents now outnumber Republicans and Democrats. Asked about Ms. Lake’s lawsuits, he says her attorneys could have saved time and money by examining the actual election results before filing “spurious claims” in court. The fact that she failed to net enough Republican voters is what mattered, not who serviced the printers.

But facts don’t seem to matter anymore, he says. “People cannot accept factual evidence contrary to their beliefs. They have a belief set. They talk to each other and endorse each other’s conspiracies.”

“I’m not going away”

A prairie wind cuts the winter sun outside the faux-industrial space where some 150 people have shown up to see Ms. Lake outside Des Moines. It’s standing room only below the exposed ducts and metal girders, and the warmup playlist could have been borrowed from a Trump rally: “Tiny Dancer,” “Gloria,” and – perhaps fittingly for a candidate who hasn’t conceded – “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough.”

Ms. Lake bounds onstage in a white blouse and tailored jeans, basking in fulsome applause. “It’s so good to be home,” she says, having grown up in Iowa.

Her message here seems more tailored to a national audience, layering her Arizona election grievances with issues like border security, fentanyl, and Ukraine aid. She mentions homeless veterans and vocational training. She takes swipes at the media – ”it’s not journalism, it’s propaganda” – and election officials who “rigged” her defeat, but her tone is as much in regret as anger.

At one point, a supporter yells “Trump VP!” to Ms. Lake’s evident delight. “My team has told me ... they’re going to think you’re running for something,” she says coyly. “And I said that’s crazy.”

Tonight, however, there’s no big reveal, just a promise of more Kari Lake. “I just want you to know I’m not going away – and I’m going to work to make sure that we have fair elections in all 50 states.”

After the speech ends, she’ll spend an hour taking selfies with a long line of fans. But before then, Ms. Lake invokes her father. A football coach and teacher, he taught her that “if you’re not in the fight, then you can’t win the fight,” she says. And – she pointedly adds – if you lose fair and square, “you congratulate the winner, and you move on.”

She pauses for a split second. “But I didn’t lose.”

Editor’s note: The spelling of Rep. Ruben Gallego’s name has been corrected, and Kari Lake’s childhood connection to Iowa has been clarified.

Amid toxic risks after train derailment, Ohio town seeks answers

After a train accident caused hazardous chemicals to spill and burn in their community, residents of East Palestine, Ohio, await answers on their long-term safety.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

EPA testing says the air is clean, and residents of East Palestine, Ohio, have been told they can go back home. Yet community members can still smell odors, and fish in local streams have died.

Two weeks after a train derailment caused hazardous chemicals to spill and burn in her community, Jessica Albright is among many residents seeking answers on their long-term safety.

“When they released us to go back home, they didn’t give us any guidance,” she says. She heard nothing about pre-washing dishes before the next use, deep cleaning curtains, and other actions to take at home. Families “don’t know what’s the right thing to do when we’re trying to protect our kids.”

A parade of emergency responders and politicians – and yesterday the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency – has come to the town trying to help. And today the Biden administration said a team of medical professionals would be deployed to provide health screenings.

State officials have advised residents in the region to drink bottled water. The EPA says it has screened the homes of roughly 500 residents so far and not found contaminants. The agency also pledges to hold railroad company Norfolk Southern responsible for cleanup costs.

Amid toxic risks after train derailment, Ohio town seeks answers

The loud clang from the railroad tracks a few blocks from her home’s back door in East Palestine, Ohio, didn’t startle Julia Slouber. Neither did the rush of emergency vehicles just moments after. It was the knock on her door from a neighbor around 10 o’clock that Friday evening that told Ms. Slouber her hometown of the past seven years was about to change forever.

You need to leave, now, the neighbor told her.

Disoriented at the thought, Ms. Slouber stepped onto her back porch in her pajamas, where she saw the blaze burning wildly less than a mile away. She couldn’t tell how close the flames were as they lapped at the night sky, stretching above the mature maple trees in her backyard. The bright beauty of that moment stunned her; Ms. Slouber could feel the heat on her face. She then rushed to grab her three cats, her insulin, and the few belongings she could carry.

“I didn’t even look back,” Ms. Slouber says, as she leans over her kitchen table.

Two weeks after a Norfolk Southern Railway freight train traveling from Pennsylvania to Illinois derailed and released tanker loads of hazardous chemicals here, a parade of emergency responders and politicians – and yesterday the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency – has come to this small Ohio town to provide updates on the issue immediately uppermost for residents: public safety.

No one died in the accident, and officials have pledged accountability and follow-through. Yet residents like Ms. Slouber still have unanswered questions, still feel they have not been well served, and still are not sure what to do or what help will come. Their quest for security and reassurance is far from finished.

“When they released us to go back home, they didn’t give us any guidance,” says East Palestine resident Jessica Albright. She heard nothing about pre-washing dishes before the next use, deep cleaning curtains, and other actions to take at home. Families “don’t know what’s the right thing to do when we’re trying to protect our kids.”

The uncertainties span from immediate safety to the longer-term future for the town and its roughly 5,000 residents.

“I have a fixed mortgage of $216 a month,” Ms. Slouber says. “What do you do?”

The early questions were as basic as what chemicals were involved in the accident. Some 38 rail cars were involved, 11 of which carried hazardous materials that contaminated the area. Ohio officials said those rail cars were not categorized as containing hazardous chemicals, so officials were unaware of the passage of such chemicals across state lines.

On Wednesday, Norfolk Southern representatives declined to attend a community meeting in East Palestine, citing fear for their personal safety.

National attention on the incident has built slowly, heightened by news footage showing the derailment’s severity – notably the massive flames and smoke of a controlled burn-off of chemicals to avoid a possible explosion.

The National Transportation Safety Board’s investigation into the incident is ongoing. Federal investigators have said the Norfolk Southern train crew received a warning about a mechanical problem shortly before an axle failed and caused the Ohio derailment.

EPA Administrator Michael Regan visited East Palestine Thursday and pledged that “we will be here as long as it takes to ensure the health and safety of the community,” and that the government will hold Norfolk Southern responsible for the cleanup costs.

On Friday, the Biden administration announced that a team of medical personnel and toxicologists will head to the Ohio town to conduct health testing and assessments.

Tensions between industry and civilians

Two weeks removed from the train’s initial derailment, a smell of burning plastic and paint still lingers in the air. A metallic taste accompanies the fumes.

The odor no longer registers with Ms. Slouber, even if those around her can still smell it. She hasn’t ventured outside much now that she’s home, but she says her headaches have become worse.

The East Palestine spill’s fallout marks the latest tumultuous chapter in the balance between civilians and industry. For this once-peaceful rural community, questions about the future outweigh official reassurances so far.

East Palestine officials care about our health because they live here, Ms. Slouber says.

But Norfolk Southern Railway? “They don’t care,” she says.

At least five lawsuits have been filed against the railroad, which announced this week that it is creating a $1 million fund to help the community while continuing to monitor air quality and remove spilled contaminants from the ground and streams.

Evacuation order

The chemical spill’s fire burned through the weekend that followed its eruption on Friday, Feb. 3. By the next week, the combustibility of the remaining hazardous waste prompted concerns of an explosion that carried the risk of deadly shrapnel fragments ricocheting across the community.

Ms. Slouber had only returned to her home a day prior to the controlled chemical burn. She recalls an Ohio state trooper approaching her home with a warning about the planned burn.

The risks led Ohio and Pennsylvania officials to enact a mandatory evacuation for those living within about 2 miles. With limited options, and through modeling conducted by the Ohio National Guard and U.S. Department of Defense, workers poked holes in the tankers, allowing the cars’ chemical contents to drain onto the porous soil, which Norfolk Southern burned to reduce contamination.

The outcome was a massive black plume that rose from the site, but it also prevented a feared explosion.

Two days later, officials told residents that, again, it was safe to return to their homes. A statement from Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said in-home air quality tests to date have found no presence of “contaminants of concern.”

Among those contaminants was vinyl chloride, a classified human carcinogen that is used to make PVC plastic. The EPA cites additional health risks from acute airborne exposure.

Incinerate the chemical, as officials opted to do in East Palestine, and it will break down into hydrogen chloride and phosgene, which both carry their own risks, according to the International Programme on Chemical Safety. Phosgene was once used as a weapon of war.

After the vinyl chloride burn-off, the EPA’s testing revealed the presence at the accident site of three more chemicals involved in the spill: ethylene glycol monobutyl ether, isobutylene, and ethylhexyl acrylate – the last of which is also classified as a carcinogen.

State officials have advised residents in the region to drink bottled water. The EPA says it has screened the homes of roughly 500 residents so far and not found contaminants.

Local residents in their frustration have been leaning on each other and on Mayor Trent Conaway, who is seeking answers on their behalf.

“You have to have a sense of humor about it,” Ms. Slouber says, referring to the importance of keeping her spirits up.

Lingering worries

Still, residents across the region believe the chemical spill’s harm is far from over.

The concern now, among the community and environmentalists alike, is that vinyl chloride will leach its way into the 14-state Ohio River Basin.

Prior to EPA Administrator Regan’s tour of the fallout zone on Thursday, the federal agency sent a letter Feb. 10 to Norfolk Southern Railway officials, noting that harmful substances released from the train’s derailment have been “observed and detected” entering East Palestine’s storm drains and nearby bodies of water, including the Ohio River’s tributaries.

Earlier this week, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources confirmed the mass die-off of at least 3,500 fish in waterways near the chemical spill’s site following the burn. But as the state agency’s director, Mary Mertz, noted in a press conference last week, researchers have not observed the same consistency in wildlife fatalities beyond the first few days after the initial derailment.

Michael Bosswell, a member of the East Palestine community for 30 years and Ms. Slouber’s son, recalls his trek down to some of his favorite fishing spots on the creek near his mother’s home following the chemical spill. Mr. Bosswell recalls seeing dead raccoons and other creatures lying along the forest floor, while dead fish and minnows floated in the creek.

“Everything eats fish,” Mr. Bosswell says, shaking his head. “The fox, the birds.”

Material from The Associated Press was used in this article.

Podcast

‘Buoyed by their resilience’: Reporting on life during wartime

Every geopolitical clash that leads to conflict delivers chaos to people on the ground – to civilians who just seek normalcy. For our reporter, it’s their perseverance that brings inspiration and hope.

War reporting can be a magnet for journalists, a career track rooted in a complicated range of motivations.

Scott Peterson began covering conflicts before he came to the Monitor. Now part of the team covering Ukraine, Scott says that applying a Monitor lens has strengthened his approach to the work.

“I think it … allows you to look at a conflict not just as a case study of human misery and despair,” Scott says on the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast, “but also one where people are finding ways to persevere ... . You find people at the extreme edges of experience. And what they are producing in response is something that is unbelievable sometimes.”

Finding those stories means managing risk. Scott’s datelines include Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004, and Mogadishu, Somalia, in the early 1990s. If you know those cities’ troubled histories, you’ll know what that means. “I’m [always] making certain decisions based on having a much broader context of what the threats are,” Scott says.

It’s in the people he meets that he sustains inspiration and hope. Scott cites the Methboubs of Baghdad, with whom he has visited over the years, including in wartime. “Every single time that I left their apartment, after hearing … about how they were just managing every single day, I was ... buoyed by [their] level of resilience.” –Clayton Collins and Jingnan Peng

This podcast episode is meant to be heard, but you can also find a full transcript here.

War Stories

Theater vérité: How ‘The Jungle’ re-creates a refugee encampment

What role do the arts play in debates about immigration? With “The Jungle,” a pair of playwrights immerse people in the migrant camp experience, aiming to prompt more discussion and understanding.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

During performances of “The Jungle” at St. Ann’s Warehouse in New York, theatergoers are inches from the action – and are sometimes handed freshly made food.

“The Jungle” isn’t dinner theater, though. Nor is it connected to the novel by Upton Sinclair about Chicago’s stockyards. Instead it’s a heavyweight drama about the migrant camp in Calais, France – called “the Jungle” – which was demolished by authorities in 2016.

The play, back in the U.S. starting Feb. 18, attempts to re-create the experience of living in that camp by placing ticket holders right in the middle of it. Sometimes it’s harrowing: Early on, fake tear gas billows through the flaps of the set’s tent. But it is also heartwarming and hopeful. By putting the audience in such close proximity to the characters, “The Jungle” aims to bring more understanding to the migrant experience.

“What I love about this play is that we don’t try to solve the problem,” says Ben Turner, who plays an Afghan refugee turned restaurant proprietor. “We’re not trying to wrap everything up in a bow. It’s messy. ... The characters are contradictory. They love, they hate, they unite. They have preconceived ideas and judgments towards each other. But then they come together in the best way.”

Theater vérité: How ‘The Jungle’ re-creates a refugee encampment

For the next month, when ticket holders enter St. Ann’s Warehouse in New York, they won’t see a conventional stage with rows, arcs, or circles of chairs. Just a vast tent.

It’s the setting for “The Jungle,” an immersive theater production. The tent is a makeshift restaurant inside a refugee camp. There’s dirt underfoot. Long tables with benches for seating and ketchup at every place setting await audience members. Ushers guide them to their places via the set’s kitchen area, which includes a dusting of flour that is more than just a prop.

“Some lucky people get some freshly made naan,” says Naomi Webb, executive director of Good Chance Theatre, the British company that created the show, opening Feb. 18. “It depends on where you sit.”

“The Jungle” isn’t dinner theater, though. Nor is it connected to the novel by Upton Sinclair about Chicago’s stockyards. Instead it’s a heavyweight drama about the migrant camp in Calais, France – called “the Jungle” by some – which was demolished by authorities in 2016. The play attempts to re-create the experience of living in the refugee camp. Sometimes it’s harrowing: Early on, fake tear gas billows through the flaps of the tent. But it is also heartwarming and hopeful. By putting the audience in such close proximity to the characters, whose stories play out on runway-style stages surrounded by the restaurant tables, “The Jungle” aims to bring more understanding to the migrant experience.

“Since the Jungle got dismantled, there’s been hardly any kind of media attention to what’s happening in Calais,” says Elena Ewence, a volunteer with Project Play, a nonprofit that gives displaced children in the area, and nearby Dunkirk, spaces and opportunities for recreation. “So the fact that [“The Jungle”] is being shown is really important because a lot of people aren’t aware of what’s going on. ... It’s really easy to forget these are real human beings.”

“The Jungle” tells the intersecting stories of several individuals who aspire to cross the channel to Britain, about 30 miles from the port of Calais. Whether by boat or tunnel, it’s a risky journey. So thousands of people set up tents and shacks in the rapidly expanding camp. Soon after an Afghan man named Salar (Ben Turner) creates his restaurant, he hosts a sort of town-hall meeting in the tent. Representatives for various enclaves – including Eritreans, Kurds, Sudanese, and Syrians – discuss how to quell violent clashes between refugees. The situation is complicated by the arrival of well-meaning, but often naive, aid workers from Britain.

“There is a big, big, big question in the play ... which is, ‘Can we live together?’” says Ammar Haj Ahmad, a Syrian actor who plays the optimistic narrator, before a recent rehearsal. “My character, at the beginning, says, ‘It takes pain to live side by side.’ And at the end of the play, he says, ‘Well, it takes pain to live side by side. It takes even more to live alone.’”

When “The Jungle” debuted in London in 2017, it was widely praised for its complexity and nuance. Call it theater vérité. Playwrights Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson based the drama on their own experiences of living in the encampment. Ms. Webb says that the British duo were en route to Munich via Calais when they visited the camp.

“They met a group of guys who said, ‘Oh, come and sit with us,’” says Ms. Webb, who later also spent time in the camp. “They played some music together and shared the story about their journey. They stayed for a week and met so many people. … And they really had a sense that everybody there really wanted to talk about what had happened to them and [tell] the stories and the journeys that they’ve been on.”

The playwrights later returned to the United Kingdom and raised money to purchase a portable geodesic dome to establish the Good Chance Theatre in the camp. (The same dome, tagged with graffiti, is mounted at the rear of St. Ann’s Warehouse where it functions as a backdrop to the set as well as a backstage area for the actors.) The cast of the first production in London in 2017 included several refugees from the camp. Some of the original cast members, including Mr. Turner and Mr. Haj Ahmad, have returned for this production of “The Jungle,” which is once again co-directed by television and theater veterans Stephen Daldry (“The Crown,” “Billy Elliot”) and Justin Martin (“The Crown,” “Prima Facie”).

“One of the first questions I asked about doing it this time around was, ‘What is the show now?’” says Mr. Turner, sitting next to a window with a view of the underside of the Brooklyn Bridge. “Stephen and Justin, after watching the show, one of the run throughs, said that actually all the narratives within the show that have always been there are suddenly feeling a lot more relevant. Like the Afghan story in this show, because of what’s going on in Afghanistan at the moment, suddenly seems to hit in a different way.”

“The Jungle,” which had a previous engagement at St. Ann’s Warehouse in 2018, takes on a different context and timbre depending on the city. The production sometimes includes question-and-answer sessions at the end of the play. When it played in San Francisco in 2019, audiences saw parallels between the characters in the story and the Bay Area’s homeless population. This time around, Ms. Webb expects there will be conversations about migrants who have been bused from Southern border states to New York. Good Chance is partnering with the Brooklyn Community Foundation’s Immigrant Rights Fund to raise money to support its work.

Ms. Ewence, from Project Play, says a person she knows who saw the play called it “very, very powerful.” “I believe it partially inspired them to come [to Calais] and volunteer.”

The honesty of the emotions opens the hearts of the audience, says Mr. Haj Ahmad, a Syrian refugee who did not experience the camp in Calais. He says he feels changed each time he performs the show.

Ruth Yemane, a new cast member, adds, “The thing with refugees in general is they’re demonized and people see them as kind of a burden. ... But I think in this play, it does a really good job of showing each individual and their journey and making them human and creating that connection.”

The characters have to bridge their own divides. For example, Mr. Turner’s Afghan character, who has a background as a lawyer, comes to discover common ground with an Eritrean woman as well as an upper-class British volunteer. The microcosm within the camp can also be viewed as a proxy for the wider issue of harmoniously integrating migrants in their new countries.

“What I love about this play is that we don’t try to solve the problem,” says the actor. “We’re not trying to wrap everything up in a bow. It’s messy. Corners are blurred. There’s a whole lot of gray. It’s not black and white. It’s contradictory. The characters are contradictory. They love, they hate, they unite. They have preconceived ideas and judgments towards each other. But then they come together in the best way.”

“The Jungle” runs at St. Ann’s Warehouse in New York from Feb. 18 through March 19, and then is at Harman Hall in Washington, D.C., from March 28 through April 16. Due to mature content, “The Jungle” is recommended for ages 12 and above.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Trust as a locomotive for rail safety

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

When a toxic spill happens, like the one from a train derailment in Ohio on Feb. 3, the first casualty is often faith in government officials responsible for public safety. In the community of East Palestine where the tragedy occurred, the town mayor displayed a certain humility about his ability to deal with the disaster.

“I need help,” Trent Conaway told residents. “I’m not ready for this. But I’m not leaving. I’m not going anywhere.”

His honesty and accountability might serve as a salve for anger over the spill, especially after the mixed or evasive responses from federal and state officials as well as the railroad company, Norfolk Southern, about both the dangers and the cleanup needed. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan acknowledged that the derailment “has understandably shaken this community to its core. ... We know that there is a lack of trust.”

Human-caused catastrophes are like pin drops, marking places such as Chernobyl and Flint as cautionary tales. In time, East Palestine may be known for something else – how trust can be rebuilt if enough officials own up to what they know and what can be done for public safety.

Trust as a locomotive for rail safety

When a massive toxic spill happens, like the one from a train derailment in Ohio on Feb. 3, the first casualty is often faith in government officials responsible for public safety. In the community of East Palestine where the tragedy occurred, the town mayor displayed a certain humility about his ability to deal with the disaster.

“I need help,” Trent Conaway told residents in a town hall meeting Wednesday. “I’m not ready for this. But I’m not leaving. I’m not going anywhere.”

His honesty and accountability might serve as a salve for anger over the spill, especially after the mixed or evasive responses from federal and state officials as well as the railroad company, Norfolk Southern, about both the dangers and the cleanup needed.

Speaking in East Palestine yesterday, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan acknowledged that the derailment “has understandably shaken this community to its core. ... We know that there is a lack of trust.” The railroad company, meanwhile, has set up emergency funds totaling more than $2 million to help residents and business owners recover.

The train that derailed was 150 cars long with a three-person crew. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) said roughly 50 cars jumped the tracks, 11 of them filled with various toxic chemicals. The wreckage left emergency responders and local officials with an untenable choice: wait for the chemical reactions triggered by the disaster to result in an explosion or burn off the substances in a controlled release. They chose the latter.

Such disasters raise questions faster than explanations can be determined or solutions put in motion. How far did the spilled chemicals spread, and how long will it take for them to break down, if at all? Did the Biden administration subordinate safety concerns in its efforts last year to avert a strike by rail workers – whose union raised such concerns?

It may take weeks for the NTSB to determine what caused the derailment. (Another Norfolk Southern train carrying chemicals skipped its tracks yesterday near Detroit.) Results from more thorough tests of soil and water are at least days away. New regulatory reforms will require long political battles.

Better understood is how environmental and infrastructure crises erode public trust. A 2014 decision in Flint, Michigan, to switch the city’s water source – the new water had contaminates that leached lead from the pipes – has left residents even today with suspicions about both the water quality and officials. “The pain from the Flint water crisis is with me every day,” Dayne Walling, who as Flint’s mayor pressed the button that switched the water sources, said years later.

Human-caused catastrophes are like pin drops, marking places such as Chernobyl and Flint as cautionary tales. In time, East Palestine may be known for something else – how trust can be rebuilt if enough officials own up to what they know and what can be done for public safety.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Our relation to God – stable and strong

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Joel Magnes

There’s value in holding to our unbreakable connection to God.

Our relation to God – stable and strong

When our granddaughter outgrew her crib, my wife and I got her a special bed with pictures of her favorite cartoon character on it. We anticipated about a half-hour for assembly.

Two hours later we were finished. It wasn’t a hard process, but every part of that bed had to be reinforced for stability and strength. We now have total confidence in its safety and integrity.

It reminded me of our – everyone’s – relation to God. It’s strong and sturdy, not affected by anything that happens in the world – not politics, climate, or strife of any kind. Our connection to God is spiritual, unbreakable, and permanent.

Sometimes it’s hard to see that. Things happen in our lives that can seem overwhelming, and we lose sight of how God – who is also called divine Love and Life and who is all-powerful – is still keeping us safe and secure. Our physical senses don’t recognize that God, divine Spirit, is continuously sustaining us.

Yet our relation to God is not about the pictures on the surface, any more than the stability of that bed came from the cartoon pictures on it. It’s about the deeper, wholly spiritual support that upholds us as God’s spiritual creation, maintaining the integrity of our entire being.

To see beyond the outward appearance of a situation and become aware of what God is doing, we need spiritual sense. In the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy says, “Spiritual sense is a conscious, constant capacity to understand God” (p. 209). This includes going beneath the surface, realizing through prayer that our connection to divine Love is untouchable and that God’s love is unwavering.

As God’s children, we all have an innate spiritual sense. And as our divine Parent, our Father-Mother God does what no human parent or grandparent can match: loves and supports each of us completely, equally, and individually – every minute of every hour. Recognizing this opens the door to harmony and healing.

That’s something we can rest in.

Adapted from the Jan. 5, 2023, Christian Science Daily Lift podcast.

A message of love

Racing through history

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. The Monitor will not publish on Monday, Feb. 20, Presidents Day in the United States. We look forward to seeing you back here on Feb. 21!