- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 12 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

An American’s daily art prayers for Ukraine

The first anniversary of the war in Ukraine has passed, but the commitment of Ukrainians to freedom has not. It continues, and in a very small way, so it does with a retired schoolteacher-turned-painter in St. Louis.

For more than a year, Marjorie Theodore has been posting daily art prayers for Ukraine on her Facebook page. They are mostly watercolors of sunflowers, and they reflect the ups and downs in the war.

Sometimes, petals fall like tears. Sometimes the face of a flower turns hopefully toward the sun. A group of sunflowers may bend low under a mighty wind. Or a white stork, which is Ukraine’s national bird, may spread its black-tipped wings and soar over the flowers.

Ms. Theodore is a friend of a friend on Facebook, and I’ve seen her images through repostings. I don’t know her personally, but over the months, I’ve marveled at the many ways she depicts these symbols of Ukraine. Every day brings a new painting, or drawing, or acrylic swirl.

Each posting is accompanied by a prayer of just a few words. They can plead for peace or cry in despair, and they embrace other troubled regions in the world. There’s also a lot of gratitude in her prayers, especially for the persistence of Ukrainians and all those who are helping them.

Last week, as the war’s anniversary approached, I called Ms. Theodore to learn more about her project and to see whether she planned to continue. How could she not? she answered. “I hope that my commitment will last as their commitment does,” she told me.

It’s so easy for people to forget wars and crises in faraway places. By posting every day, even if only 25 or 35 people give a thumbs-up or make a comment, she knows that Ukraine is in their thoughts, however briefly, and that’s just what she is hoping for.

She explained it this way:

“I do think art is prayer. I think that song is prayer. When you are thinking of someone that you love, that is prayer. So when I think of Ukraine and I express my feelings through these daily pictures, it is a prayer.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Can police police their own? NYPD as a case study.

The NYPD has been the nation’s foremost laboratory of police reform. So as the country wrestles with how best to find ways forward on policing, New York stands out as a crucial case study.

With some 36,000 officers, the New York Police Department is the largest police force in the world, and the most influential department in the country. In many respects, too, the NYPD has been the standard-bearer of tactical innovation and management reforms over the past three decades.

“The NYPD does kind of stand out as an exemplar among American police departments, specifically within the American policing community,” says Jorge Camacho, policy director of Yale Law School's Justice Collaboratory and a former Manhattan assistant district attorney. “By and large, NYPD officers are better trained than most officers in most other jurisdictions. They do have more oversight over them. Not to say that it’s perfect oversight. They just have more.”

But others see an inherent flaw: How can police, in effect, police themselves and punish their own? And is this a matter of “a few bad apples,” or are the current structures of police training and accountability deeply flawed?

For Samy Feliz and about 50 others gathered in front of City Hall, the NYPD’s tactical innovations and an astonishing drop in violent crime and police shootings have come with a terrible cost for the Black and Latino communities that have borne its relentless focus on high-crime neighborhoods: the number of young men, like Mr. Feliz’s brother, who have been shot and killed.

Can police police their own? NYPD as a case study.

In 1994, when Joseph Giacalone was just two years and change on the job with the New York Police Department, he found himself in the middle of a shootout at a warehouse in the Bronx.

It would be the first and only time he’d fire his gun at a suspect.

After a decorated, two-decade career, the experience in that warehouse continues to shape his understanding of the issues surrounding police reform. That’s especially true, he says, after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in 2020 and the killing of Tyre Nichols at the hands of five Memphis police officers in January.

Wielding the power of the state and given the duty to enforce its laws, police officers have a responsibility like few others in society, he says. It’s one of the reasons he now teaches his students the fundamentals of criminal investigation and the use of force, emphasizing the importance of training, professionalism, and accountability.

“When I look at the Derek Chauvin case [in Minneapolis], and now looking at the Memphis videos, the first thing that stands clear in my mind is: no supervision,” says Mr. Giacalone, now an adjunct professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. “There’s no supervisor on the scene in either case. Now, would a supervisor have prevented this? I believe so, because something went inherently wrong with these individuals.”

“And I would say none of it had to do with their training, because no one is trained to do the things they did,” he says. “It’s about supervision. It’s about accountability.”

With some 36,000 officers, the NYPD is the largest police force in the world, and the most influential department in the United States. In many respects, too, the NYPD has been the standard-bearer of tactical innovation and management reforms over the past three decades. It has been the nation’s foremost laboratory of police reform. So as the country wrestles with how best to find ways forward on policing, New York stands out as a crucial case study. To understand the past 30 years is to begin to understand how policing has gone right and how it has gone wrong.

“The NYPD does kind of stand out as an exemplar among American police departments, specifically within the American policing community,” says Jorge Camacho, policy director of the Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School and a former assistant district attorney in Manhattan. “By and large, NYPD officers are better trained than most officers in most other jurisdictions. They do have more oversight over them. Not to say that it’s perfect oversight. They just have more.”

When it comes to the reform of American policing, however, the idea of accountability remains one of the most bitterly contested. Mr. Giacalone and other experts see it as an essential value of management and professionalism.

But others see an inherent flaw – one that, at its worst, leads to the killing of Americans. How can police, in effect, police themselves and punish their own? And is this a matter of “a few bad apples,” or are the current structures of police training and accountability deeply flawed?

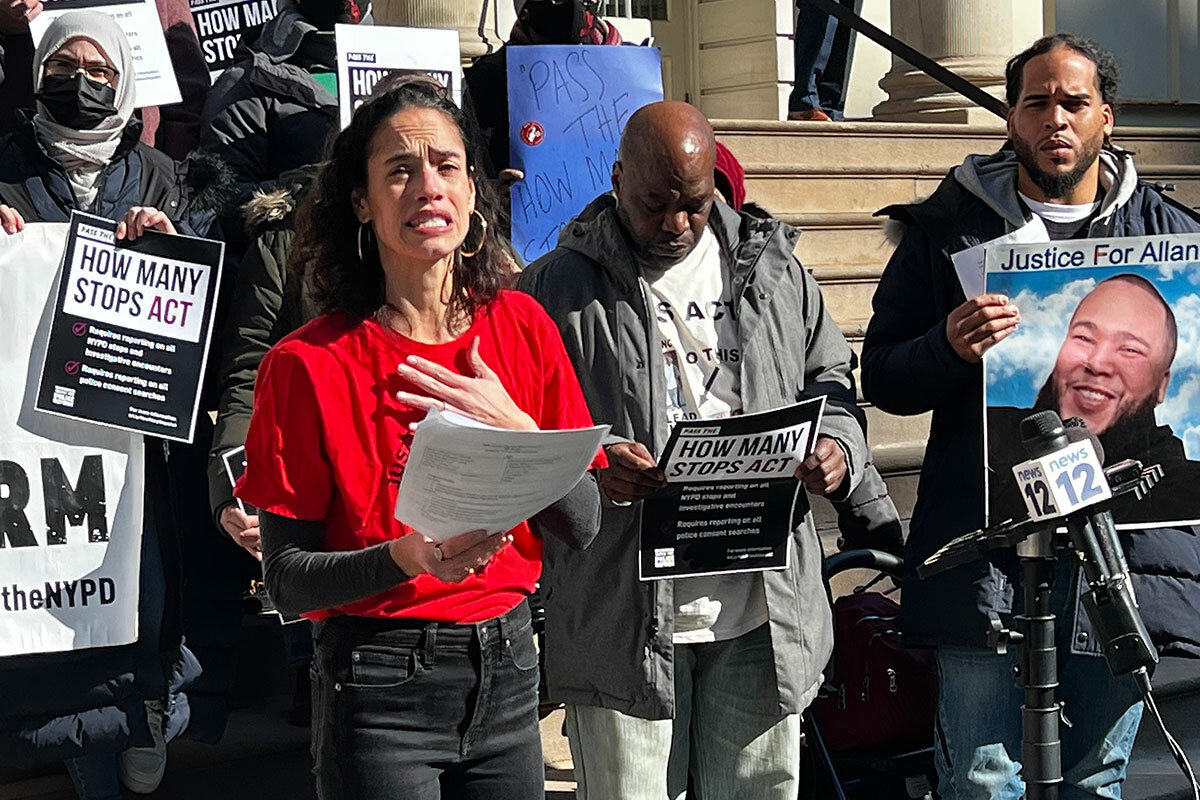

“We’ve seen time and time again how routine police stops have ended tragically,” says Alexa Avilés, a member of the New York City Council, speaking at a rally in front of City Hall calling for the NYPD to provide more data about its day-to-day methods and interactions with people on the street. “When is enough ever going to be enough? ... We want to know, with taxpayer dollars, are they doing the job that we are trusting them to do in the public?”

Councilwoman Avilés’ call for rigorous public transparency includes a fundamental opposition to one of the NYPD’s paradigm-shifting tactical innovations, begun 30 years ago: the relentless and data-driven focus on the city’s most crime-ridden neighborhoods.

Mr. Giacalone’s career with the NYPD, most of which he served as a supervising sergeant, spanned that era. In the early 1990s, when he was a rookie cop, the “mean streets” era of New York was reaching its ignominious peak: There were around 2,000 murders each year, and violent crime and armed robberies were reaching all-time highs.

The year he fired his weapon at a suspect was also one of the most transformative years in the history of the NYPD – and perhaps in the history of American policing. In 1994, the NYPD launched CompStat, short for “comparison statistics,” and started to pioneer the methods of data-driven policing.

It was also the time when the department began to reorganize the kinds of special anti-crime teams that would influence those like Memphis’s now-disbanded SCORPION unit. Instead of solving crimes that already happened, police would work to prevent them. Using techniques like stop and frisk, traffic stops, and minor violations like loitering and littering, the department would focus laserlike on getting illegal guns off the streets.

Mr. Giacalone says it was also around that time that the NYPD began to revamp its own systems of accountability, including for officer-involved shootings, which were happening hundreds of times per year. In the early 1970s, officers discharged their firearms almost 1,000 times annually.

In 1994, when Mr. Giacalone fired his .38 revolver at a suspect, it was one of 331 officer-involved shootings, according to NYPD data. That year, some 29 people were killed.

He and his partner responded to a report of a disturbance at a Bronx warehouse. An armed robbery was in progress: A crew from Brooklyn was attempting a heist of cable boxes.

“When we walked into the door of the place – it was into, like, a garage area – there was a break from the sun into this dark garage, so it took a second for your eyes to kind of adjust,” says Mr. Giacalone, who was responsible for the actions of 10 officers under him during his years as a sergeant. “But there was a guy with a gun, tying someone’s arms,” he says. The suspect immediately started shooting at them.

Mr. Giacalone says his NYPD training immediately kicked in. “Cover and concealment is something ingrained in your head, so that when you hear shots, you react,” he says. “You don’t even think about it.” He and his partner both dived behind a nearby van and returned fire. Then they “waited for the cavalry to arrive,” he says.

In the end, no one was shot or injured. Specialized units arrived, including hostage negotiators and canine units, and the suspects surrendered. They were eventually convicted and sent to prison.

Officers put their lives on the line every day, he says. Any routine call can suddenly turn into a life-or-death situation, a fact that makes policing a different kind of profession.

But 1994 was also the year in which crime began to fall dramatically, beginning what criminologists call “the great crime decline” of the past three decades. Murders in New York City fell from a peak of 2,262 in 1990 to just 292 in 2017, the fewest in the city’s history and an astonishing 88% drop. Since then the number of murders in NYC jumped to 438 in 2022 – a record short-term increase, but still 80% lower than in the early 1990s.

The number of officer-involved shootings also fell dramatically. In 2017, on-duty NYPD officers discharged their firearms 37 times, killing nine people. In 2022, there were 48 police shootings, in which 11 people lost their lives.

After he fired his gun, Mr. Giacalone immediately entered what could be called a protocol of accountability. Internal Affairs officers took his .38 revolver and inspected it. He and his partner were informed of their rights under General Order 15, a kind of Miranda rights for police, which gives them 48 hours to consult with an attorney before giving a statement.

“We didn’t need a lawyer, as far as I was concerned,” says Mr. Giacalone. “We had a union delegate there, and we just told our story.”

In early February, Samy Feliz stands in front of New York’s City Hall, demanding accountability for the NYPD officers who shot and killed his brother 3 1/2 years ago.

His brother, Allan Feliz, had been pulled over during a routine traffic stop in Washington Heights for what police say was a failure to wear a seat belt – a fact the Feliz family and its lawyer dispute after analyzing the three videos of the shooting, including police body camera footage and a bystander video.

The passengers in the car can be heard saying they were wearing seat belts. When the officers ran his brother’s ID, they found he had three outstanding warrants for tickets, including one for littering.

According to the videos, an altercation ensued, and police shocked Mr. Feliz’s brother with a stun gun. As one officer struggled with him in the front seat, the father of a 6-month-old can be heard yelling, “Don’t shoot me, don’t shoot me!” During the struggle, the car moved forward slowly, and then backward. Police say the brother, who served five years in prison for burglary, was trying to get away. The family says it was the police who caused the car to move during the struggle. One of the officers, a supervising sergeant, then fatally shot Mr. Feliz in the chest. As officers dragged him feet-first from the car, his pants and underwear were pulled down.

“This kind of disrespect and violence is the rule, not the exception,” says Samy Feliz, holding a picture of his brother in front of him as he recounts how Allan was shot and killed in the middle of an October afternoon, just as schools were letting out. Officers “yanked his body out of the car, exposing his genitals and leaving him, at 3 in the afternoon, for the world to see – kids walking home from school.”

For Mr. Feliz and about 50 others who have gathered in front of City Hall, the NYPD’s tactical innovations and the astonishing drop in violent crime and police shootings in New York have come with a terrible cost for the Black and Latino communities that have borne its relentless focus on high-crime neighborhoods: the number of young men who have been shot and killed.

“The vast majority of the time it’s just a few horrific stories of police killings that make it into the news,” says Gabby Cuesta, a leader in a coalition of civic groups and family members of those killed by police called Citizens United for Police Reform. “What this fails to show is that police killings are just the tip of the iceberg. ... [There are] thousands of examples of daily violence experienced by members of Black, Latinx, and other communities of color in New York City because of constant, disparate low-level enforcement and broken-windows policing that does not keep us safe.”

In some ways, the genesis of the coalition was after the fatal shooting of Amadou Diallo in 1999. A cadre of plainclothes officers called the Street Crime Unit, whose stated motto was “We own the night,” approached the student from Guinea, who was returning to his apartment in the early morning hours. When Mr. Diallo reached for his wallet, the four officers opened fire, shooting 41 rounds, 19 of which struck and killed the 23-year-old immigrant.

The NYPD did not discipline the officers, and they were acquitted of murder. But the department disbanded the unit.

It was in many ways the first of what became a national focus on police shootings. At the same time, however, activists and others began to scrutinize the NYPD’s tactics, including its growing emphasis on stops and frisks.

In 2001, the City Council passed legislation requiring the NYPD to provide its data on these stops – which proved to be one of the most momentous reforms for police accountability. The department’s own data revealed that police were stopping hundreds of thousands people each year, and about 85% were Black and Latino men. All it took was a “furtive glance” to justify a body search.

In 2012, groups that were part of the Citizens United for Police Reform coalition filed a successful lawsuit against the NYPD. In 2014, a federal judge ruled the NYPD’s stop and frisk practices violated the Constitution, illegally profiling people of color and violating the standards for “reasonable suspicion,” the threshold for conducting a search. The judge placed the NYPD under a federal monitorship, which continues today.

“While that was a huge win after years and years of organizing, the abuse continues,” says Samah Sisay, staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, which filed the successful federal lawsuit. “We know stop and frisk is still a reality in the city and the ways implemented? What we saw in the racial disparities that continue, are causing immense harm.”

In 2021, there were almost 9,000 stops and frisks, according to NYPD data, and 87% were of Black or Latino people.

The purpose of the rally in front of City Hall, in fact, was to call for passage of the How Many Stops Act, which would require the NYPD to provide the same kind of data for lower-level stops, including searches with consent. Data like this helped prove that the NYPD’s practices were unconstitutional, so activists hope to use it to continue to expose what is happening in their communities.

“These bills are going to bring critical and urgent transparency to the NYPD daily activities in our community,” says Ms. Cuesta. “Right now, the NYPD is only required to report on what we know as stop and frisk. That leaves the vast majority of encounters unreported.”

Community members, too, are concerned that Mayor Eric Adams has relaunched the kind of street crime units of the past as the city is experiencing a record increase in violent crime coming out of the pandemic.

After the Memphis Police Department disbanded its SCORPION unit after the killing of Mr. Nichols, Mr. Adams defended the efficacy of the technique, and the kinds of reforms the NYPD has put in place.

Now known as the Neighborhood Safety Teams, they are not completely a plainclothes unit, but wear identifying markings. Mayor Adams has touted its new methods of training, including de-escalation techniques, robust oversight, and a selection of officers who will not, he’s said, perpetuate “the abuses that we witnessed in the past.”

“Many people stated that we should not do it, but we were able to remove 7,000 guns off our streets; that’s a 27-year high,” he told CNN. “A combination of body camera footage is crucial, having the right supervision there, that can immediately de-escalate the situation or stop when it gets out of hand, and pick the right officers assigned. Just because you are a police officer does not mean that you are capable of doing every aspect of policing.”

The department also now provides a public database that allows users to view the records of NYPD misconduct allegations. Activists won another major victory for transparency in 2020 after New York repealed its Civil Rights Law 50-a, which long shielded the disciplinary records of NYPD officers from public view.

Mike Hayes, an investigative journalist who has long had “an obsession with disciplinary records,” remains skeptical. He says the administration of the database is “half-baked,” noting that a number of officer records he’s obtained are missing from the database.

“When the mayor talks about how last year the NYPD pulled 7,000 guns off the street, that is something that should absolutely be commended and is definitely a stat that you like to see,” says Mr. Hayes, author of “The Secret Files: Bill de Blasio, the NYPD, and the Broken Promises of Police Reform.”

“But I’ll push back on that and say, ‘Tell us how many of these guns were taken off the street by Neighborhood Safety Teams officers. Where are they operating?’” he says. “And as we sit here today, we don’t know who these officers are. That information has not been put out there in a very transparent way.”

Mr. Feliz, whose family has filed a wrongful death suit against the NYPD and is still waiting for the findings of the Citizens Complaint Review Board, says he continues to be profiled in his neighborhood and stopped by police for no reason.

“I can be waiting for a table outside of a restaurant, and I have a Neighborhood Safety Team officer asking me, ‘What’s going on? What are you doing?’” he says. “They asked me if I had anything on me, so I allowed them to conduct their search. Why? Because the entire time I’m having this experience with this officer, he has his hands on his holster and his gun like John Wayne.”

“That’s an intimidation tactic; that’s a coercion for me to allow him to check me,” Mr. Feliz continues, describing the kinds of lower-level stops that are not currently part of the public record. “That’s not anything that makes me as a New Yorker feel safe or reassured. ... It’s not a problem with ‘a few bad apples’; it’s a systematic lack of transparency and accountability.”

Editor’s note: The number of murders in New York City in 2022 has been corrected. There were 438.

The Explainer

Defamation: Dominion's case against Fox

Dominion Voting Systems says Fox News hurt its business by airing election falsehoods. The lawsuit is revealing how much the network was focused on its bottom line – and telling its viewers what they wanted to hear.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Recently released court filings are providing a window into a lawsuit by Dominion Voting Systems alleging defamation by Fox News, set to go to trial in April.

Following the 2020 election, the Denver-based company became a target of pro-Trump activists, who claimed Dominion had manipulated vote counts to make Joe Biden the winner. Former President Donald Trump tweeted on Nov. 12, 2020, that Dominion had “deleted” 2.7 million votes for him. His legal advisors, Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell, alleged a criminal conspiracy.

The company, which supplies voting machines to 28 states, refuted these allegations, as did U.S. election officials. There is no evidence that any votes cast on Dominion machines or software were manipulated to change the outcome of the election.

But Fox News gave ample airtime to the Trump allies making these claims of voting-machine fraud. Court documents indicate that Fox executives knew the claims were false but chose not to intervene for fear of losing viewers who believed them.

Fox’s lawyers say the network was covering newsworthy events – a U.S. president disputing an election – and that it didn’t endorse the views of the public figures who appeared on its shows. The network denies defamation and calls its coverage protected free speech.

Defamation: Dominion's case against Fox

Recently released court filings are providing a window into a lawsuit filed by Dominion Voting Systems against Fox News and its corporate owner, set to go to trial in April.

Dominion alleges defamation by Fox, which aired baseless claims by President Donald Trump and his allies about Dominion’s voting machines used in the 2020 election.

Court documents indicate that Fox executives knew the claims were false but chose not to intervene for fear of losing viewers who believed them. Fox has denied defamation and called its coverage of election-fraud allegations protected free speech.

What is the basis for Dominion’s defamation lawsuit?

The Denver-based company, which supplies voting machines to 28 states, became a target after the Nov. 3, 2020, election. Pro-Trump activists claimed that Dominion had manipulated vote counts to make Joe Biden the winner. President Trump amplified these claims, tweeting on Nov. 12 that Dominion had “deleted” 2.7 million votes for him. His legal advisors, Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell, claimed to have proof of a criminal conspiracy by Dominion and of links to Venezuela’s socialist dictatorship.

The company refuted all these allegations, as did U.S. election officials who used the machines. There is no evidence that any votes cast on Dominion machines or software were manipulated to change the outcome of an election that Mr. Biden won by narrow margins in swing states.

Fox News, the most-watched cable news channel, gave ample airtime to Mr. Trump’s allies to question the validity of the 2020 election. Both Mr. Giuliani and Ms. Powell appeared daily on prime-time shows where they accused Dominion of flipping votes to Mr. Biden.

Dominion says that Fox’s airing of falsehoods has damaged its business. The company has lost contracts in some states and faced pushback in others where officials cited 2020 fraud conspiracies as a reason not to use its technology. Several employees have also faced threats.

Dominion has also sued Newsmax, a competitor to Fox that tried to outflank it in amplifying 2020 election-fraud conspiracies. This competition weighed on Fox hosts and executives, who worried about losing viewers to Newsmax if they didn’t lean into the conspiracies, according to depositions and internal communications made public in court filings.

As the preeminent conservative news outlet, Fox is a highly symbolic target. Its efforts to appease aggrieved Trump voters in 2020 – to show “respect” to the audience, as executives emphasized – must be understood in this context, wrote New York Times columnist David French. Fox is “no mere source of news. It’s the place where Red America goes to feel seen and heard.”

The court filings suggest a strong disconnect between what Fox was broadcasting, largely uncritically, about alleged voting-machine fraud and what producers, hosts, and executives were saying internally about the allegations and the individuals who were making them.

In a deposition, Rupert Murdoch, the chairman of Fox Corp., admitted that some Fox presenters had endorsed what he called “really crazy stuff” and that he regretted not intervening. Tucker Carlson and other top-rated hosts privately disparaged Ms. Powell, in particular, and even called her a liar. Still, she continued to appear on prime-time shows to speak about Dominion. And when a Fox reporter tried to fact-check Mr. Trump’s tweet about Dominion deleting his votes, Mr. Carlson told fellow hosts Sean Hannity and Laura Ingraham that the reporter should be fired.

“Please get her fired. Seriously. ... It’s measurably hurting the company. The stock price is down. Not a joke,” he wrote in a text.

What is Fox’s defense and how robust are free speech protections?

Fox’s lawyers say that the network was covering newsworthy events – a U.S. president disputing the results of an election – and that as a news organization it didn’t endorse the views of the public figures who appeared on its shows.

News organizations enjoy broad First Amendment protections, and defamation cases rarely make it to trial. Under a standard set by a 1964 Supreme Court ruling, plaintiffs must show that a news outlet knowingly aired falsehoods or showed a reckless disregard for the facts.

The Supreme Court wanted to allow for “innocent mistakes” so that public debate wouldn’t be chilled by libel suits, says George Freeman, a former in-house counsel at The New York Times who directs the Media Law Resource Center. “It’s a hard test, but it’s a hard test deliberately,” he says. “You have to prove that something nefarious was in the editor or reporter’s mind.”

In its filings, Fox News has derided “cherry picking” by Dominion of what Fox staffers said about Mr. Trump’s allegations. It argues that skepticism among some employees doesn’t mean that that organization writ large was at fault in airing false statements about Dominion.

This line of defense is likely to play out at trial, says Jane Kirtley, a professor of media ethics and law at the University of Minnesota. Even if Fox executives didn’t buy Mr. Trump’s claims but wanted to protect their ratings, opinion hosts could still claim that they were keeping an open mind about Dominion and election fraud.

What may prove harder for Fox to defend, says Ms. Kirtley, is that Dominion said it sent more than 3,600 emails and other communications to Fox to correct the record, but that Mr. Trump’s allies were invited to keep repeating their falsehoods, day after day. “If this had happened once we never would have had this lawsuit. It's the fact that it went on repeatedly,” says Ms. Kirtley. Fox’s hosts “knew what these people were going to say.”

What is the broader significance of the case?

The case has become something of a proxy for the 2020 election dispute and the spread of misinformation that led up to the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. Opponents of Mr. Trump, including many Democrats, would like to see a reckoning for those who pushed his false narrative – even if that means seeing a private company prevail over a news network.

At the same time, the case could have consequences for press freedom if Fox appeals an unfavorable ruling and a conservative-dominated Supreme Court decides to revisit the 1964 standard for defamation, says Ms. Kirtley. That possibility makes her and other First Amendment scholars uneasy.

“I wish this case would settle. I’d rather it never had an opportunity to go to the Supreme Court,” she says.

Dominion is seeking $1.6 billion in damages from Fox. While victory for Dominion wouldn’t put Fox out of business, it would be costly. It underscores that a case freighted with political baggage is, at its core, about commercial interests on both sides.

For Fox, reporting too critically on Mr. Trump’s baseless fraud claims was demonstrably bad for ratings, since many viewers were drawn to a rigged-election narrative, even if the facts didn’t support it.

For Dominion, the fact that millions of Trump voters believe the election was rigged – a belief that Fox promoted relentlessly – has made it harder to do business in Republican-run jurisdictions.

In his deposition, Mr. Murdoch was asked why Fox hosts kept booking Michael Lindell, a pillow retailer and Trump backer who promoted false theories about the election, as a guest. (Dominion has separately sued Mr. Lindell for defamation.) Mr. Murdoch pointed out that Mr. Lindell spent a lot of money to air pillow commercials on Fox.

“It is not red or blue,” Mr. Murdoch said. “It is green.”

Patterns

Russia's war machine and the West's clean energy drive

Among the many unintended consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine is one silver lining: new impetus for the use of green energy sources.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Of all the aftershocks from Vladimir Putin’s attempted military takeover of Ukraine, one of the least likely could prove the most significant: a decisive global shift toward greener energy.

That’s because one of the war’s main effects has been to drive home the political cost of energy dependency on a country that is ready, able, and determined to use it as leverage.

Last year, for the first time, total world investment in clean energy was roughly equal to the $1.1 trillion invested in fossil fuels. That is not enough to meet the international global warming target, but it has brought the green energy transition possibly a decade closer.

The key accelerator of that transition has been government money – hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of subsidies to develop, produce, and use green energy technology – deployed in deliberate policy shifts by Washington and the EU.

Among their motives? They’re acting with an eye toward another potential dependence: on China, the world’s most generous source of green energy subsidies, having spent nearly $300 billion on them last year alone.

The transition trend is quickening, largely because the world is more aware of the political imperatives driving that trend. And it is Mr. Putin’s war that has brought them into focus.

Russia's war machine and the West's clean energy drive

Of all the aftershocks from Vladimir Putin’s attempted military takeover of Ukraine, one of the least likely could prove the most significant: a decisive global shift toward greener energy.

The trend had been building even before the Ukraine war, as businesses, investors, and political leaders began positioning themselves to reap the benefits of an economic future based less on fossil fuels, such as oil, gas, and coal, than on clean energy sources like wind, the sun, and hydrogen.

But the pace was nowhere near fast enough to reach the climate target that environmental experts say is needed to avoid the worst effects of global warming – limiting the Earth’s temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels.

That’s still a very tall order, but there are growing signs that Mr. Putin’s war has brought the transition to a lower-carbon energy future closer – by five or even 10 years, according to one recent report by Britain’s Economist newsmagazine.

It has certainly boosted funding for greener energy and technology. Another report, published by Bloomberg’s NEF research group in January, calculated that last year’s total world investment in clean energy was, for the first time, roughly equal to the $1.1 trillion invested in fossil fuels.

And the green energy momentum seems set to grow. All three of the world’s fossil fuel powerhouses – China, the United States, and the 27-nation European Union – have been rolling out massive new subsidies to encourage investment in green power and technology.

The role that Mr. Putin’s war is playing in this has been complex, indirect, and – like so much else about his invasion – unintended.

Russia’s interests lie in more fossil fuel use, not less. Oil and gas are mainstays of its economy.

And the sharp decrease since the invasion in imports of Russian natural gas by its key customers – EU countries – has indeed led to a short-term increase in demand for coal, slowing a concerted international effort in recent years to phase it out.

The war’s main effect, however, has been to drive home the political price of energy dependency on a country that is ready, able, and determined to use it as leverage.

While Mr. Putin expected – or at least hoped – that western Europe’s enormous reliance on Russian gas would weaken its commitment to Ukraine, it has instead served as a wake-up call.

Alongside greater use of imported liquid natural gas from countries other than Russia, European countries are seeing an increased takeup of noncarbon energy sources, such as solar panels and heat pumps, which use outdoor air to heat homes.

Poland, for example, is a major user of coal, much of it traditionally imported from Russia. Air pollution had already been prompting greater use of solar panels and heat pumps. But since the Ukraine invasion, purchases of heat pumps have more than doubled.

Still, the key accelerator of the green energy transition has been government money – hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of subsidies to develop, produce, and use green energy technology – deployed in deliberate policy shifts by Washington and the EU.

Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act in the U.S. earmarked nearly $400 billion for clean energy subsidies, and the EU is moving in a similar direction. President Joe Biden has said he is committed to fighting climate change, and the EU has long taken a lead in international efforts to slow global warming.

But the EU and the U.S. are also anxious to avoid the political perils of relying on imported energy – a lesson painfully learned from the Ukraine war.

And they’re acting with an eye toward another potential dependence: on China.

China is the world’s second-largest economy. It is by far the largest source of carbon emissions. But it is also the world’s most generous source of green energy subsidies, having spent nearly $300 billion on them last year alone according to BloombergNEF.

And China is also the leading producer of solar panels and the batteries used in electric cars.

So while the Ukraine war has provided a major catalyst for global investment in green energy, it has also set the stage for a subsidy competition among the U.S., the EU, and China – a kind of climate change protectionism.

That could lead to supply bottlenecks as each of the players moves to build a robust, homegrown green energy economy.

And even last year’s record trillion-dollar investment in green energy worldwide remains far from enough to reach the international goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. That will require five times that amount every year by 2030, according to the Europe-based climate think tank E3G.

Yet the transition trend is now quickening. And that’s not just because the world is more aware of the dangers of climate change.

It is also because of a growing recognition of the political imperatives, and potential economic benefits, of moving toward a green energy economy.

And that is a message magnified, however tragically, by Vladimir Putin’s war.

As iconic Florida crop fades, another tree rises

With disease threatening their crops, orange growers in Florida aim to meet adversity with ingenuity – even if that may mean leaving a storied tradition behind.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Xander Peters Special correspondent

The citrus industry, long a defining symbol of Florida, is facing an existential crisis. A plant disease that arrived in the state in 2005 has spread to affect 80% of the state’s orange groves. The number of growers has already plunged, and, partly due to hurricanes, the state’s current growing season is expected to yield 61% less fruit than last season.

Cody Estes, a third-generation grower, has had to cut down and burn what had been his most productive trees.

What he does still have is a willingness to adapt. He and other farmers aim to chart a path of ingenuity that can keep agriculture – and its livelihood for workers – in the state. Various alternative crops are being tried, and Mr. Estes is exploring one of the most promising ones, a tree called pongamia.

In parts of Asia, pongamia grows wild as it bears little beanlike pods that, in India, are crushed and used for lamp oil. Other uses can include biofuel production, fertilizer feedstock, and a more sustainable alternative to soybeans for protein. The trees also are hardy, require relatively little water, and can be harvested using a mechanized shaker.

“It just really feels like it’s going to work,” Mr. Estes says.

As iconic Florida crop fades, another tree rises

Every spring, the sweet smell of citrus blossoms permeates the air on the Estes family farm in Vero Beach, Florida. The family has grown and harvested citrus on this land for more than a century.

“The smell used to filter into town,” the farm’s third-generation owner Cody Estes says, smiling.

But despite their heritage and deep connection to the industry, Mr. Estes doubts he’ll ever plant another citrus tree in the groves. Eventually, his family’s plan is to leave Florida’s $6.5 billion industry to invest in a new, imported crop, much as citrus was before European colonizers brought the Asia-derived fruit to North American shores. Anything else he puts in the ground, Mr. Estes says, will be a tree called pongamia.

The citrus industry, long a defining symbol of Florida, is facing an existential crisis due to a plant disease that arrived in the state in 2005 and has spread to affect 80% of the orange groves. In 2004, Florida had an estimated 7,000 growers. Today, there are about 2,000. If the latest estimates hold, the state’s current growing season will yield 61% less fruit than last season, partly due to hurricane effects.

The Estes family’s most productive trees have been cut down and burned.

Back at his office, Mr. Estes leans back in a chair and crosses his hands over his chest. Years after the arrival of what’s called citrus greening disease, “we really don’t have a good answer,” he says.

What he does have is a willingness to adapt. He and other farmers aim to chart a path of ingenuity that can keep agriculture – and its livelihood for workers – in the state. To do that, a first step is to prove that new crops like pongamia fulfill their promise.

“The alarm bells were rung”

In 2005, Michael Rogers felt the citrus industry shake beneath his feet. Mr. Rogers, director of the University of Florida’s Citrus Research and Education Center, was sitting in a meeting with a large citrus processing company when he felt his phone buzz in his pocket. A text from a colleague read, “It’s here.”

Mr. Rogers texted back, “What’s here?”

The colleague replied, “HLB.”

Huanglongbing, or citrus greening, has been documented in China for at least a century, but it hadn’t reached the Western Hemisphere’s shores until 2004, when it was recorded in Brazil – the world’s leading citrus producer. Prior to greening’s arrival, the pathogen was so feared that the U.S. Department of Agriculture classified it as a potential bioterrorism weapon that could be used against the nation’s agricultural sector.

“The alarm bells were rung very loudly,” Mr. Rogers says. “It’s like one of those moments where everybody knows where they were when they heard the news.”

In the ensuing years, some headway has been made in understanding the role of bacteria in citrus greening.

Growers rethought fertilization techniques, as well as how – and when – they irrigate crops, with water pumps that have features such as moisture sensors. In the estimate of Jim Hoffman, Estes Citrus’ production manager and an industry veteran of two decades, the fight against greening’s effects has made more efficient farmers through their increased attentiveness to the health of groves and new technologies.

“We’re more purposeful with our resources,” Mr. Hoffman says. “We’re farming smarter.”

A protein-rich, hardy alternative

Ideas for new crops have arisen as farmers try to keep the land in use, such as blueberries, cotton, alfalfa, eucalyptus, and sugar beets. Polk County citrus growers Henry Hooker and his sister Deborah Hooker partnered with the HBCU Florida A&M University and Green Earth Cannaceuticals to grow legal hemp.

But pongamia carries the most promise so far, says Peter McClure, whose family’s roots in Florida citrus date to the seedlings his great-grandparents planted in Orange County in 1868. Mr. McClure is also the chief agriculture officer at Terviva, the California startup helping lead pongamia’s commercialization through partnerships with farmers like Mr. Estes.

In India, Australia, and parts of southeast Asia, pongamia grows wild as it bears little beanlike pods that, in India, are crushed and used for lamp oil. Terviva hopes to corner the tree’s American market; their plan, use it for biofuel production, fertilizer feedstock, and a more sustainable alternative to soybeans for protein.

Like citrus, pongamia grows in Florida’s unforgiving sandy soil. Unlike citrus, though, pongamia is mostly pest-resistant, has a lower cost of production, is drought-resistant, and can withstand wet conditions, and it requires minimal inputs. In fact, it requires a fraction of the irrigation necessary to keep citrus trees healthy. And unlike labor-intensive citrus, the pongamia can be harvested using a mechanized shaker.

It’s also how Mr. Estes and Mr. McClure found themselves working together.

Just like citrus soared in the economic boom that followed World War II, they envision a potential pongamia boom today, helping to meet the rising demand for climate-friendly agriculture.

“With pongamia, we have a different confluence of factors,” Mr. McClure says of their goals. “Huge numbers of people in Asia are becoming affluent. When you become affluent, you want more protein.”

Mr. McClure adds, “North America’s plowed up. Asia’s plowed up. To feed the next 3 billion people, you’d have plow up the Amazon and Africa, which isn’t a good idea. That’s where pongamia comes in.”

Mr. Estes’ pongamia groves are four years or so away from production. They expect the trees’ output to max out as a mature crop around the time each tree reaches its eighth year.

The pongamia crop “holds the promise that we can continue farming, provide for our families, and leave a gentle footprint on the land,” says Mr. Hoffman, the Estes Citrus manager.

Wrestling with uncertainty

In September, Hurricane Ian rolled over southwest Florida, surging with 4 feet of water into homes in North Fort Myers. It also affected citrus farmers in Desoto, Hardee, and Polk counties (though dodging Indian River County where Mr. Estes lives). Some crops were reported as a total loss – a severe blow to an already struggling industry.

Government can only aid their industry for so long. Measures like a box tax that funds research about citrus greening may help. If nothing else, some farmers hope to find an alternative so they can pass the land along to family, rather than sell the land to developers that will pave it over.

As his children grew up, Mr. Estes steered them away from the family citrus business, because it’s so difficult to make a living. But he wants to keep their land alive for his grandchildren. He hopes they’ll follow him into pongamia.

Citrus equates to family for Mr. Estes. Asked whether removing the citrus trees his grandfather planted 45 years ago feels like a turning of the page, he takes his time. A sly half-smile sneaks across his face.

“I often wish that he was still here to debate some of the issues,” he says. “It takes decades to have enough experience to know what you think will work, and it’s not something you can just learn from a book – or learn from a year or two of experience.”

Mr. Estes opens the door of his truck and climbs outside. He’s standing in front of what, someday, will be the beginning of the farm’s pongamia grove. The trees are still young and shrubby. Estes looks at the trees and then back out at the dying groves around him.

He puts his hands on his hips, turns around and says, “It just really feels like it’s going to work.”

Coffee without end: Oasis village tests limits of hospitality

How generous is too generous? In the Saudi oasis village of Jubbah, where doors are never closed, hospitality that once served as a lifeline for desert travelers pushes politeness, and guests’ capacities, to the limits.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In the palm-lined Saudi oasis village of Jubbah, residents provide hospitality as extreme as the desert elements – even too extreme for some locals. “You will enjoy it,” says an Uber driver in Hail who has family in Jubbah. “But they will host you until it hurts.”

Jubbah is a village whose residents never close their doors, an invitation for anyone to walk in unannounced. “Here you are judged by your hospitality,” says tour guide Rami Shimri, pouring coffee at his home at the entrance to Jubbah.

Once the invitations begin, in home after home, it’s an endurance test of politeness – and the stomach. A culinary cycle quickly emerges: coffee, dates, tea; coffee, dates, tea, and biscuits; coffee, dates, fruit, and tea.

Hosts do not take “no” for an answer. “Please show us mercy, we have already drunk 20 cups of coffee today!” says one Saudi visitor. “I can’t have another date,” says another, clutching his stomach.

“Just put the coffee pot down,” a Saudi guest says to his host, in a break from Arab etiquette. “This is only the introductory coffee,” the host says, stone-faced. “I invite you for an informal coffee at my residence out back. Now, please eat.”

Coffee without end: Oasis village tests limits of hospitality

Alighting from an Uber at the souq in downtown Hail, the reporter gets a warning from his young driver about his next destination.

“Don’t eat or drink before you go to Jubbah,” he says.

It’s an odd and ominous warning to receive in Hail, a northern Saudi region so famous for hospitality that it has inspired centuries-old Arabic poems and modern Youtube videos – and where you are never more than a few minutes away from your next lunch invitation.

But in the palm-lined oasis village of Jubbah, 72 miles north of Hail in the desert, where generosity toward guests was ingrained in generations who endured severe hardship, residents provide hospitality as extreme as the elements – even too extreme for Hail locals.

“You will enjoy it,” advises the driver, who today lives in Hail but has family back in Jubbah, “but they will host you until it hurts.”

Jubbah is a village whose residents never close their doors – really – an invitation for anyone to walk in unannounced for coffee, dates, tea, a meal, or to spend the night.

“Our prophet taught us: Be generous to your guests,” says village resident Ayed bin Mohammed al-Ayadeh, who, like his great-grandfather before him, greets guests at his ancestral home and farm with dates and cookies. “Which is why our entire community and daily routines revolve around hosting.”

As Jubbah residents pursue generosity with a religious zeal, they compete for guests: Who gets to host them and serve them lunch? Those left off a visitor’s itinerary can become upset.

Village of open doors

On a Saturday in February, the doors to Jubbah homes both small and large are open.

“Welcome!” one resident calls as visitors walk past his open gate, waving them to enter. “Hello!” beckons his neighbor from the garden.

Jubbah residents typically reserve about 70% of their home for guests – including an ornate majlis guest hall with plush chairs and a fireplace, courtyard, sleeping quarters, a bathroom with perfume, even parking – leaving a few small, spartan rooms in the back for themselves.

Most of the courtyards open onto the main road to make it easier to flag down an out-of-towner.

“Here you are judged by your hospitality,” tour guide Rami Shimri says, pouring coffee in his father’s plush majlis. “You have to have a majlis and you have to be on call for any visitor. It is our way.”

Entering Jubbah from the south, Mr. Shimri’s family home is the first of dozens whose owners will invite you in.

It is by design; his father selected this location at the outskirts so that their majlis would be the first to greet visitors with coffee and incense.

And so, the invitations begin, from home to home. It’s an endurance test of politeness – and the stomach.

Within an hour of being pulled into different guest halls a culinary cycle emerges: coffee, dates, tea; coffee, dates, tea, and biscuits; coffee, dates, fruit, and tea.

Hosts do not take “no” for an answer. Even covering your cup with your hand fails to stop the coffee flowing.

“Please show us mercy, we have already drunk 20 cups of coffee today!” says one Saudi visitor. “I can’t have another date,” says another, clutching his stomach.

“Just put the coffee pot down,” a Saudi guest says to a teenage host eager to pour a third cup. It’s a break from Arab etiquette in which the guest always defers to the host. “Just. Put. The. Coffeepot. Down.”

“This is only the introductory coffee,” the host says, stone-faced. “I invite you for an informal coffee at my residence out back. Now, please eat.”

Hardship hospitality

It may seem forceful, but residents say it is a hospitality shaped by hardship.

When the ancestors of today’s residents settled this oasis 500 years ago, upon a dried lake and ancient hunting grounds in the heart of the Nafud desert, they relied on and improved existing artesian wells that were already many centuries old, Jubbah historians say.

They dug and fortified 130-foot-deep wells in the sand, often deadly work, to collect groundwater and rainwater. Teams of two camels would pull up the pails of water in a mill system.

For the ensuing centuries, before modern agriculture took root in the mid-20th century, villagers struggled to grow crops beyond date palms. Separated from the nearest town by dozens of miles of desert, they relied mainly on dates, ghee, and wheat kernels to feed their families.

“It was from this hardship, fear, and near-starvation, that the community of Jubbah formed a sense of solidarity and a life-or-death concept of hospitality,” says Nasser al-Shaweini, a local historian and curator of the Nasser Shaweini Museum. “It was a self-reliance that prized what little that they had, and shared with others.”

Mr. Shaweini guides museum visitors to an oriental carpet and a large platter of bananas, apples, kiwis, and oranges.

“We lacked resources, but had hospitality in abundance.”

This hospitality was a lifeline for travelers.

Jubbah was a vital stop for caravans coming from the Levant down into Hail and further into the Najd region of central Arabia. The route took them through the harsh, 40,000-square-mile Nafud desert that stretches from today’s Jordan down into Hail.

Travelers would arrive in Jubbah, two-thirds of the way across the Nafud, parched after six arduous days.

The visitors and their camels would be greeted with water that residents would immediately pump into pools and troughs at the front of their homes, through canals that still exist today.

The guests were fed dates, wheat, and ghee – for days or weeks – and upon their departure were given a large batch of dates to sustain them on the next leg of their desert journey.

“The best dates, ghee, wheat, whatever we had were set aside for visitors and guests,” says Mr. Ayadeh, dipping a date into a ghee-date molasses syrup and handing it to a visitor, “because we didn’t know when the next time our guests would eat, find water, or rest after they left.”

Tourism without hotels

Jubbah, which now boasts trained tour guides, is looking to share its unparalleled hospitality – and wealth of sites – with world visitors.

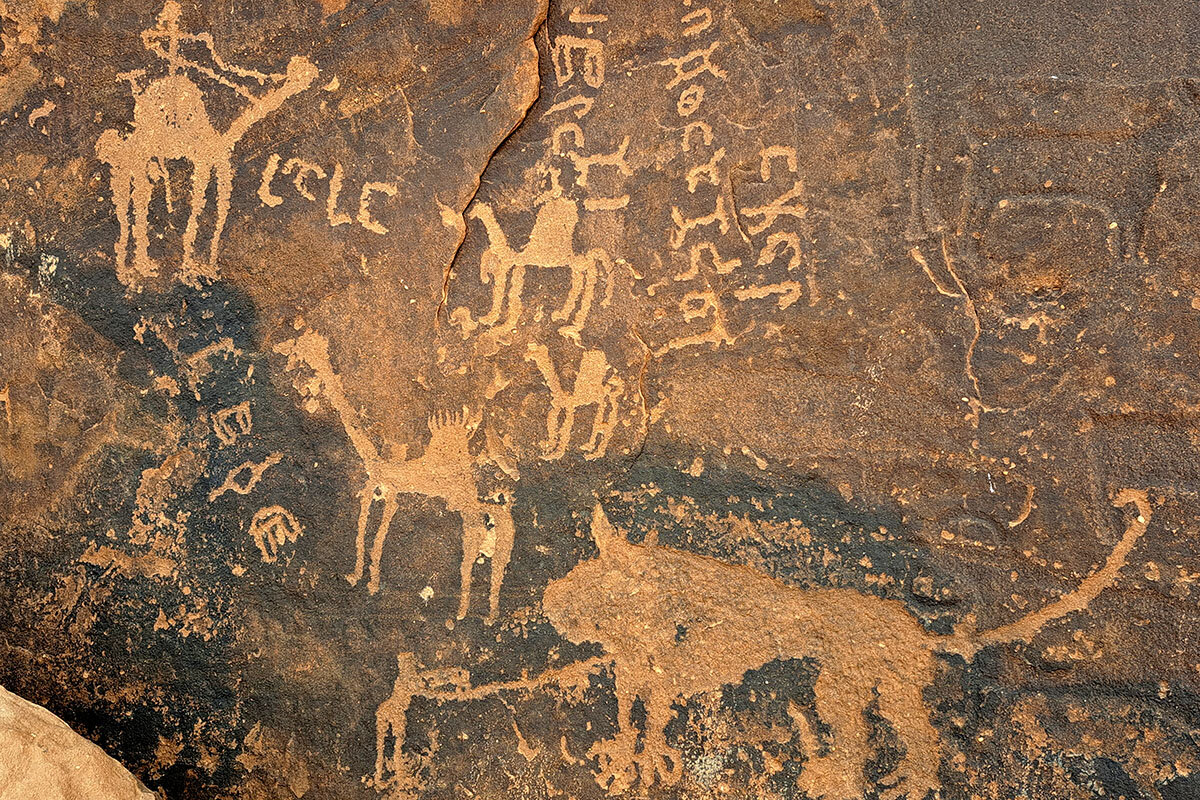

The village is eager to showcase its breathtaking ancient rock art and petroglyphs, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2015. There are also nearby desert camping sites, and idyllic date farms and mud-brick homes across the village.

Several residents have expanded their ancestral guest halls into cultural museums at their own expense to showcase the area’s history – in between dates and coffee for their guests.

Despite the push for tourism, hotels are forbidden, as far as Jubbah residents are concerned.

They are eager to offer their traditional rooms to visitors to spend the day or night – preferably several – for free.

“We always have a room for visitors to rest and stay. This is the least we can do and it would be shameful to monetize it,” Mr. Shaweini says as he shows off his cushioned guestroom.

Leaving is a challenge. Only a series of excuses and a race through the town avert multiple dinner invitations. Several people in the street wave at the departing vehicle, urging the visitors to pull over and stay “for just a little while longer.”

Two days later, at the Hail Airport, a stranger quizzes the reporter on where he had visited.

“I am from Jubbah,” the stranger exclaims. “Why didn’t you tell us you were coming? We would have readied the coffee pot for you!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Building blocks for compassionate cities

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A year after being elected to lead the city of Boston, Mayor Michelle Wu stood on the steps of a vacated church in February to fulfill a promise to reinvent how the city cares for its residents. The building is part of a $67 million project to lift up low-income neighborhoods. Seventeen unused buildings and empty lots will be remade into more than 800 income-restricted units for rent or ownership, combined with artist studios, shop fronts, health clinics, and after-school centers.

The project is one of the more innovative ideas playing out across the United States as municipal planners and private developers grapple with how to ensure cities provide adequate housing for both existing and new residents. In many cities, that requires redressing historical harms caused by eminent domain or anti-blight laws that allowed city officials to appropriate homes or overrun whole neighborhoods.

Ms. Wu’s strategy centers on creating, as she said, “climate resilience and healthy, connected communities.” Developers, citizens, and city officials are struggling to agree on what her goals will require. That may be more unifying than it sounds. Removing obstacles to adequate housing will require broad and democratic discussion, one marked by humility and openness.

Building blocks for compassionate cities

A year after becoming the first woman and person of color to be elected to lead the city of Boston, Mayor Michelle Wu stood on the steps of a vacated church in February to fulfill a promise to reinvent how the city cares for its residents.

The building is part of a $67 million project to lift up low-income neighborhoods. Seventeen unused buildings and empty lots will be remade into more than 800 income-restricted units for rent or ownership, combined with artist studios, shop fronts, health clinics, and after-school centers.

The project is one of the more innovative ideas playing out across the United States as municipal planners and private developers grapple with how to ensure cities provide adequate housing for both existing and new residents. In many cities, that requires redressing historical harms caused by eminent domain or anti-blight laws that allowed city officials to appropriate homes or overrun whole neighborhoods.

It also means adjusting to economic changes, such as a boom in tech industries, that can leave cities like Boston too expensive for people in service jobs or low-salaried professions like teaching. “We can’t grow sustainably unless our residents are secure in their homes,” Ms. Wu said in her first State of the City address in January.

In some cities, like Washington, minimum-wage workers must clock 80 hours per week to afford a one-bedroom unit. The 2022 Greater Boston Housing Report Card found that Boston’s rental and homeowner vacancies were among the lowest in the country.

Ms. Wu’s strategy centers on replacing the city’s planning and development board and banning the use of anti-blight laws that enabled city officials to seize buildings they decided were dilapidated or otherwise undesirable. In its place, the mayor has proposed a new board under her office to create, as she said at city council meeting, “climate resilience and healthy, connected communities.”

Developers, citizens, and city officials are struggling to agree on what her goals will require. That may be more unifying than it sounds. Removing obstacles to adequate housing will require broad and democratic discussion, one marked by humility and openness. Mayor Wu’s project to renovate and renew 17 sites across Boston’s diverse neighborhoods is a start toward refashioning a city with compassion for all.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

God’s knowledge is power

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

When taken from a divine standpoint, the saying “knowledge is power” gains new meaning, as a man found after he became stuck under a car’s transmission.

God’s knowledge is power

English philosopher Francis Bacon observed, “Knowledge is power.” Academic knowledge is certainly useful and important! But I’ve found that taking the concept of knowledge a step further – turning to what God knows – is particularly helpful, especially when we’re in trouble. Over and above what the physical senses report to us about ourselves, we can go to God in prayer for knowledge about the spiritual facts of being, which has tangible benefits.

The knowledge and power of God are humbling. When we honor God over our own sense of the world, we realize we don’t know it all and it’s OK to ask God for help. A good way to understand what God sees of His creation is first to examine the nature of the creator. God, whom the Bible describes as Spirit and Love, has no physical attributes and is, therefore, without physical vulnerabilities or limitations.

That which divine Spirit creates must logically reflect the nature and essence of its creator. Each of us has been generously gifted with an identity that is entirely spiritual and entirely good. In our true nature as God’s likeness, we are unlimited and undeterred by physicality, including all the liabilities that come with a material view of life.

And because God is the divine Mind, all His children have the ability to understand spiritually. It doesn’t need to take years of practice to learn to turn to God for knowledge and strength, but rather an honest openness to Mind’s inspiration. Even as a young boy, Jesus leaned on God, divine Spirit. The Bible says about him, “The child grew, and waxed strong in spirit, filled with wisdom” (Luke 2:40).

Christ Jesus’ identity and role as the Son of God were certainly unique. But his example is for everyone, and he made it clear that all are able to open themselves up and be filled with God’s wisdom, too. This understanding trust in God’s knowledge and power, Jesus proved, brings freedom, melting fear and completely curing ailments. Beyond blind faith, when our trust is founded on some degree of growing understanding of God and His creation, we have a strong basis for finding healing.

In “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy’s groundbreaking book on God, prayer, and healing, we find this helpful counsel: “Rise in the strength of Spirit to resist all that is unlike good. God has made man capable of this, and nothing can vitiate the ability and power divinely bestowed on man” (p. 393).

This was proven to me palpably one time when I was lying on my back underneath my car, replacing the clutch. The transmission slipped and came down squarely on my chest. I was alone in the garage and it didn’t seem I had the strength to free myself.

As I prayed, it became clear that if I saw myself as merely a physical being, I couldn’t do much – my strength and abilities were limited. Yet as a sense of myself as divine Spirit’s image expanded in my thoughts, my fear changed to confidence. And I then found I was able to lift the transmission off my chest and even get it back into its spot under the car.

The clear knowledge we gain from Mind certainly does empower us. It helps us find a solid trust in what’s right and what’s real. It’s a joy to become open to God’s presence and power like that.

Prayer can be a simple yielding to God’s loving, always-present strength and intelligence. We can ask for God’s help in understanding what is spiritually real, and experience how tremendously fulfilling it is to glorify God in this way. As the Bible puts it, “The Lord give thee understanding in all things” (II Timothy 2:7). Then, as we grow in trusting God’s knowledge, our fear dissipates and God’s power shines through.

Viewfinder

Hands across the water

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a video from our multimedia team that focuses on deconstruction – a progressive industry emerging as an alternative to the demolition of buildings.

Note: Our friends over at the Common Ground Committee, a bridge-building organization, have produced a new podcast episode that looks at the search for solutions to gun violence, and at differences in regional attitudes on guns. The Monitor’s Patrik Jonsson is one of the two main guests. Here’s where to find this episode of “Let’s Find Common Ground.”