- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How hard is parenting? Readers respond.

Last month, I shared the results of a Pew survey of parents’ views about raising children. Topping their concerns were mental health, bullying, and safety. Longer-range, most expressed hope that children would simply live stable, satisfying lives. And many said parenting was harder than they expected. So I asked readers: Is parenting harder today?

Karin Heath, a mother of three who has worked with young people for decades, says yes. Just look at cellphones, she says – amazing tools, but also a relentless lure into a world that often spurs negative comparisons with peers and a misguided sense of what others’ lives are really like.

“When I’m able to limit the time the young people in my care have their cellphones in their hands,” she says, “their behavior improves exponentially.”

Some raised the issue of children’s agency. Eric and Marian Klieber wrote of their “hope parents can get better at stepping back – without losing sight, of course, of when to intervene. Children empowered by their ability to make decisions about their lives at appropriate ages will usually turn out fine.”

Another lauded the greater duty-sharing between moms and dads. It’s “a definite improvement in family life,” writes Carol Lambert.

There was clear common ground on the need for love and commitment from older folks toward the younger ones in their lives. “I’ve learned that nothing is more vital … than for [young people] to have an adult in their lives who loves them and will engage with them,” says Ms. Heath. That can include the village that raises a child. As reader Helen Young wrote, “I will pay more attention to these concerns that touch parents’ and families’ lives so deeply.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As China weighs arms for Russia, Taiwan is on its mind

Will China use its military resources to give Russia an edge on the battlefield? Although the Ukraine war has propelled cooperation between Beijing and Moscow, China’s calculations in Eastern Europe have more to do with the United States.

Beijing possesses enough Russian-style military hardware and munitions to help tilt the Russia-Ukraine war in Moscow’s favor and undermine efforts to restore Ukraine’s sovereign territory.

So far, no evidence has emerged showing Beijing has sent weapons to Moscow, and experts say the decision to do so would depend largely on China’s long-term concerns about the possibility of conflict in Asia, particularly with the United States and Taiwan. If U.S.-China relations worsen further, Beijing’s incentives to draw closer to Russia and possibly provide weapons and other military assistance – albeit as covertly as possible – will also mount.

“Beijing might want to provide lethal aid to Russia,” even at the price of a major punitive response from the West, says China Power Project fellow Brian Hart. “Russia is China’s most powerful partner on the world stage, and Beijing does not want Russia to be strategically weakened by the war.”

Yet even then, rather than make a “rash decision” to send Russia military equipment, China is more likely to expand military cooperation over time, says Michael Raska, assistant professor and coordinator of the Military Transformations Program at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “We will see this gradual augmentation, rather than massive trains of arms going from China to Russia.”

As China weighs arms for Russia, Taiwan is on its mind

As Russia slogs into the second year of its war in Ukraine, facing a mounting toll in lives and treasure, Moscow is increasingly desperate for an infusion of lethal aid from the country that’s already serving as an economic lifeline – China.

Indeed, Beijing possesses ample, Russian-style military hardware and munitions that could help tilt the battle in the Kremlin’s favor and undermine efforts by Kyiv and its Western supporters to restore Ukraine’s sovereign territory.

Washington recently stepped up warnings to Beijing after U.S. intelligence indicated China is considering providing its northern ally with weaponry – reportedly including artillery shells and attack drones used in front-line combat. So far, no evidence has emerged showing Beijing has made such transfers, U.S. officials say.

Yet Beijing’s calculations on whether to supply Russia with arms have less to do with the trajectory of the fighting in Europe than with its own long-term concerns about the possibility of conflict in Asia, experts say – particularly “about future confrontation with the U.S.,” says Alexander Korolev, senior lecturer in politics and international relations at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

Beijing’s view, he says, is that China and the United States “are clearly on a collision course, so we will need Russia.”

If U.S.-China relations worsen further, Beijing’s incentives to draw closer to Russia and possibly provide weapons and other military assistance – albeit as covertly as possible – will also mount. “The most likely issue which might lead to further deterioration is obviously Taiwan,” says Chen Cheng, professor of political science at the University at Albany, SUNY.

A senior Chinese official recently drew a rare direct comparison with Taiwan while underscoring how Beijing views Ukraine through the lens of regional competition with America.

“Why does the U.S. ask China not to provide weapons to Russia, while it keeps selling arms to Taiwan?” China’s new top envoy, Foreign Minister Qin Gang, said at a Beijing press conference on March 7. “Why does the U.S. talk at length about respecting sovereignty and territorial integrity on Ukraine, while disrespecting China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity on China’s Taiwan question?”

Fast friends

A year ago, China and Russia – united by their authoritarian ideologies and desire to counterbalance the U.S.-led system of alliances – elevated their relationship with a no-limits friendship pact. In a historic joint statement in February 2022, they pledged to support each other’s “core interests,” including China’s claim to the self-governing island of Taiwan, and Russia’s interests in Ukraine and other border regions.

Soon afterward, Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, and Beijing has since refrained from condemning it, instead blaming the U.S. and NATO for the conflict.

Indeed, as Western sanctions on Russia have taken hold, experts say the Ukraine war has in some ways accelerated the linkages between the two countries – diplomatically, economically, and in their incentives to cooperate militarily. Beijing has backed Moscow in the United Nations, while disseminating Russian propaganda on the war.

A recent Chinese peace plan for Ukraine also reiterates Russia’s assertions that the West provoked the conflict, calling for a cease-fire and end to sanctions, while presenting Beijing as a neutral mediator. China’s leader Xi Jinping reportedly will travel to Russia to meet with President Vladimir Putin next week, and afterward hold his first phone call since the war started with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy.

Economically, cooperation between China and Russia has accelerated in the past year, as trade boomed, especially in energy and food. Russian crude oil exports to China increased 8% last year, while its annual natural gas exports are rising and are expected to grow by a quarter by 2026.

Military cooperation is also growing, as Russia and China expand joint exercises in Asia – both for training and to send a message to Washington. “They’re not preparing to fight under a joint command or anything like that, but military exercises have certain training benefits to both of their militaries, and they send a strong signal to the United States,” says Joseph Torigian, assistant professor at the School of International Service of American University in Washington.

Western sanctions have heightened Russian dependence on China for dual-use items such as semiconductor chips, spare parts for helicopters and other equipment, and drones as well, and in the longer term, some analysts predict the war will act as a catalyst for a new and more closely integrated military relationship.

Sino-Russian interdependence

Historically, Russia has played a key role in China’s military development, providing tremendous amounts of assistance starting in the 1950s. China imported and also produced Soviet-designed weapons such as tanks, fighter jets, and missiles. Such cooperation was derailed during the Sino-Soviet split of 1960, but resumed after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990 – with China receiving more than $21.5 billion worth of arms from Russia between 1992 and 2005, according to the Stockholm International Peace and Research Institute.

But in recent years, China’s defense modernization has improved its production capabilities and made the country less dependent on Russia, setting the stage for a partial role reversal, experts say.

“Beijing might want to provide lethal aid to Russia,” even at the price of a major punitive response from the West, says Brian Hart, a fellow with the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Russia is China’s most powerful partner on the world stage, and Beijing does not want Russia to be strategically weakened by the war.”

Moreover, he says, “the war keeps Moscow reliant on China as a lifeline and critical geopolitical partner, and it has also distracted the United States and its allies.”

Some analysts believe the Ukraine war could even spur an integration of Russian and Chinese defense programs, if lingering historic mistrust and different standards can be overcome. The two sides reportedly are already cooperating on early-warning systems for ballistic missile defense.

“The war in Ukraine is helping to accelerate these ideas … because Russia and China will need each other more and more,” says Michael Raska, assistant professor and coordinator of the Military Transformations Program at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore. “The Russians will … increasingly rely on Chinese high-tech components for their weapons … and the Chinese would want key Russian technologies, say microchips and high-tech materials,” he says.

Rather than make a “rash decision” to send Russia military equipment for immediate needs in Ukraine, China is more likely to expand military cooperation to meet its long-term goals in competing with the U.S., Dr. Raska adds.

“We will see this gradual augmentation, rather than massive trains of arms going from China to Russia,” he says. “Russia needs high tech, and Chinese have leverage – what can they get in return?”

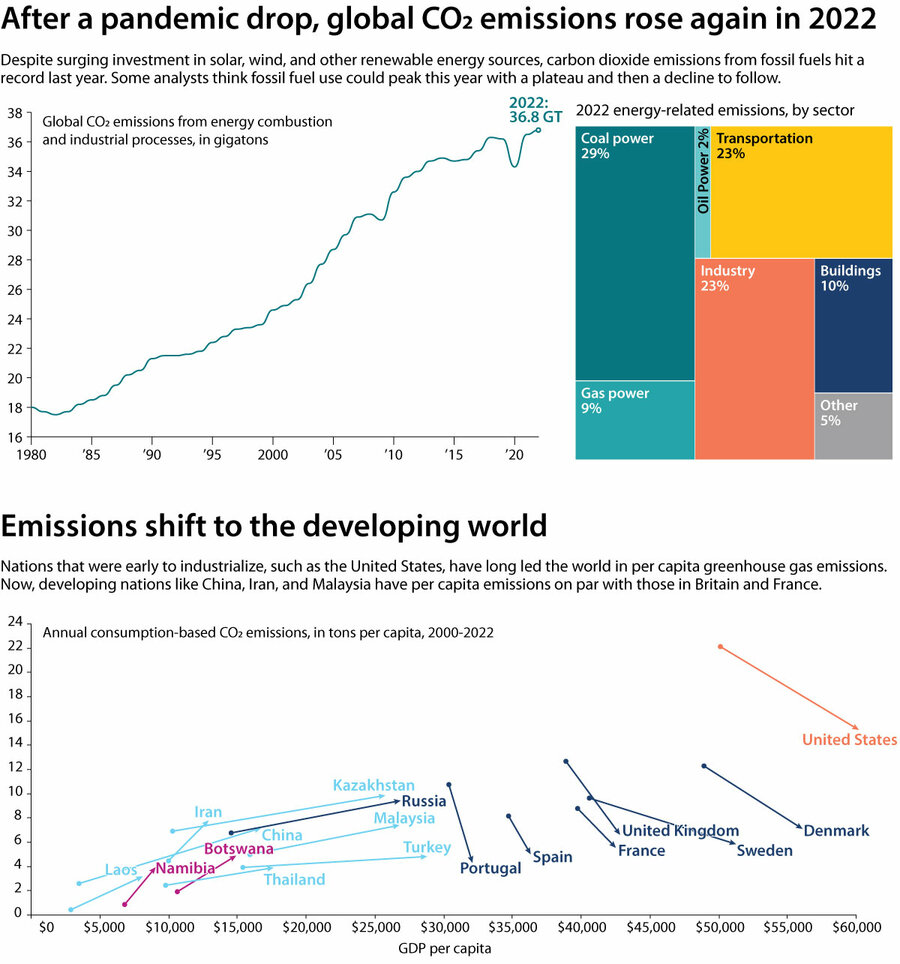

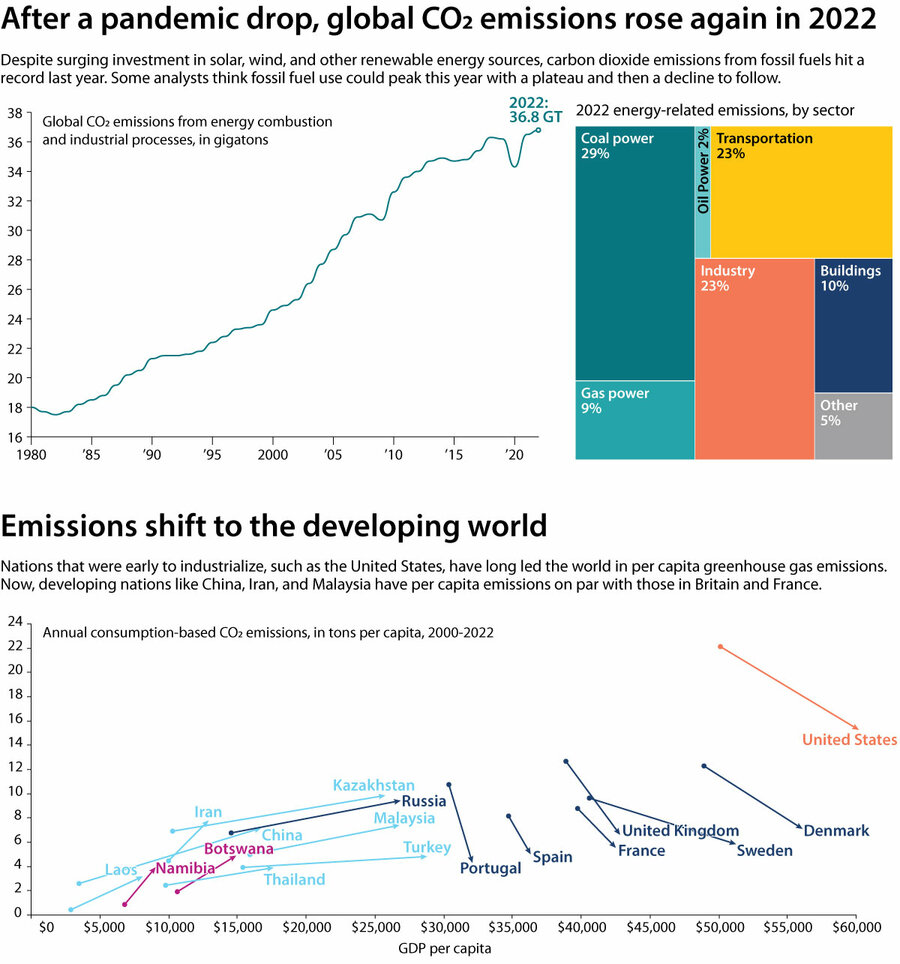

Renewables surge, yet carbon emissions hit record. What gives?

How can the world be massively shifting toward renewables and boosting its overall carbon emissions at the same time? We parse the progress in a global transition that’s far from finished.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The world’s emissions of heat-trapping carbon dioxide rose to record levels last year, according to a new report from the International Energy Agency, but renewable energy sources continued their exponential growth – and some analysts believe that the world’s fossil fuel demand has peaked.

If that seems like contradictory news for the world’s climate, that’s because it is, says Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist with RMI, an energy and climate research organization.

Welcome to the half-full and half-empty world of climate action in the 2020s. This decade is shaping up as a transition point toward increasing reliance on clean energy, even as fossil fuel use hasn’t yet started to decline. It is a moment when nations are touting their moves toward zero-carbon economies, even as many are also approving new fossil fuel exploration.

But this report, says Rachel Cleetus of the Union of Concerned Scientists, shows that technological change is not enough to fix the climate crisis. It’s also about mindsets, influence, and societal priorities.

“It pulls you up short to realize, ‘Wow. We can have the technologies. They’re fully deployable. So what’s standing in the way?’” she says. “But this has never been just a problem about technology. It has always been about power and politics and money.”

Renewables surge, yet carbon emissions hit record. What gives?

The world’s emissions of heat-trapping carbon dioxide rose to record levels last year, according to a new report from the International Energy Agency, but renewable energy sources continued their exponential growth – and some analysts believe that the world’s fossil fuel demand has peaked.

If that seems like contradictory news for the world’s climate, that’s because it is, says Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist with RMI, an energy and climate research organization.

Welcome to the half-full and half-empty world of climate action in the 2020s. This decade is shaping up as a transition point toward increasing reliance on clean energy, even as fossil fuel use hasn’t yet started to decline. It is a moment when everyone from corporations to politicians to financial institutions is touting moves toward zero-carbon economies, even as governments across the world – including the Democratic U.S. administration – approve new fossil fuel development.

The report, the international agency’s latest annual effort to crunch energy-related greenhouse gas data from multiple countries, paints this complicated picture: There are key points of hope and optimism, but also the reality that the world continues to send heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere at unprecedented levels.

“The reason it’s terrible news is that we still have very high levels of emissions,” Mr. Bond says. “The reason, however, that it’s good news is that emissions have peaked and we’re basically on a plateau.”

This matters because for decades, climate research has pointed toward a clear conclusion: Sending more greenhouse gases into the air means the world’s temperature will increase. The global warming caused by human emissions is already starting a cascade of environmental and human challenges, scientists say, from extreme weather to sea-level rise to crop failures. And they predict it will get worse for each fraction of a degree that the Earth heats.

International Energy Agency, Our World in Data based on the Global Carbon Project

“We really do need to get [emissions] down because we have a serious carbon budget that we need to adhere to if we want to avoid the worst impacts of climate change,” says Doug Vine, director of energy analysis at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

International Energy Agency analysts found that global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions – the largest source of human-caused greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – rose by under 1% in 2022. This is far less than many researchers had predicted, especially given the global energy crisis and conflict in Ukraine, which many had thought would create a spike in emissions.

In Europe, for instance, the agency’s analysts found that rather than increasing, emissions dropped 2.5%. That’s despite Germany resurrecting or extending the life of at least 20 coal-fired power plants, and despite the temporary offlining of a number of nuclear power plants, which provide low-emission energy.

Strong energy conservation efforts in Europe, such as turning down the thermostat and switching over to heat pumps, helped cause this drop, aided by a mild winter. The region’s increasingly rapid turn toward renewable energy sources also helped prevent a spike in greenhouse gas emissions.

“Renewables is what has saved us from Russian energy blackmail,” says Mr. Bond, who is based in Britain.

Indeed, energy analysts say that without the rapid, global rise of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, the emissions picture would be far worse.

“The impacts of the energy crisis didn’t result in the major increase in global emissions that was initially feared – and this is thanks to the outstanding growth of renewables, EVs, heat pumps and energy efficient technologies. Without clean energy, the growth in CO2 emissions would have been nearly three times as high,” Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency, said in a press release.

But coal, known as the highest-emission energy source, is still on the rise – particularly in developing countries. Emissions from Asia’s emerging market and developing economies (excluding China) rose far more than those in other regions, according to the report – some 4.2%. Over half of these came from coal-fired power generation.

And it’s not as if other fossil fuel sources are going away yet.

In the United States, for instance, emissions increased slightly, by 0.8%, but the country also increased its use of natural gas by some 89 megatons. (Although sometimes praised as “cleaner” than coal, natural gas is still a fossil fuel that releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. It also is connected to the release of methane, a greenhouse gas that is shorter-lived but traps more heat than carbon dioxide.) A good percentage of this natural gas was used for air conditioning, thanks in part to unusual heat waves across the country – a sign, analysts say, of the way that the causes and effects of climate change can spiral.

Around the world, oil emissions also increased last year, in large part because of a rebound in the aviation industry, the report found.

“I was particularly surprised by the stubbornness of energy-related emissions, which continued to rise despite some very strong headwinds, including an apparent decline in overall emissions from China (another major surprise), the ongoing energy crisis in Europe, and record additions of alternative energy sources,” Akos Losz, senior research scholar at the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, wrote in an email.

For researchers like Rachel Cleetus, policy director with the climate and energy program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, the continued fossil fuel emissions are proof of the need for more sweeping, systemic change.

“We need to be cutting emissions by 6% to 7% a year now,” she says. “This trend of continued growth is just very, very sobering. It’s off track from where we need to be.”

For years, she says, she and others involved in climate research have looked toward renewables as an answer to the crisis of global warming. Finally, this technology not only exists, but is also proving economically competitive with fossil fuels. Policies such as the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act are poised to give renewables even more of a boost – something financial analysts like Mr. Bond see as indication that renewables will soon become the world’s dominant energy sources.

But this report, Ms. Cleetus says, shows that technological change is not enough to fix the climate crisis. It’s also about mindsets, influence, and societal priorities.

“On the technology side there’s only good news here. ... The technology is more than performing. For those of us who have been doing this work for a couple of decades, it’s beyond our wildest dreams. And that’s when it pulls you up short to realize, ‘Wow. We can have the technologies. They’re fully deployable. So what’s standing in the way?’ But this has never been just a problem about technology. It has always been about power and politics and money.”

International Energy Agency, Our World in Data based on the Global Carbon Project

The Explainer

Family detentions? Why Biden is tacking right on immigration.

President Joe Biden’s recent shift on immigration policy shows the challenge of balancing order and compassion. It may also reflect concerns about a coming surge at the border, following the rollback of a pandemic-era measure.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

On the campaign trail, then-candidate Joe Biden promised to reform the country’s immigration system by undoing many of the policies put in place by former President Donald Trump.

Now, more than two years into President Biden’s term, his administration is reportedly considering reinstating the practice of detaining families that cross the U.S. border illegally – a policy Mr. Biden previously criticized and that his administration had largely ended. The Department of Homeland Security has been relying on alternative approaches, such as allowing families to enter the country with tracking devices while their immigration cases move forward.

The potential reversal suggests that President Biden, like many of his predecessors, is struggling with how to balance order with compassion at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Many experts say it also reflects growing concerns in the administration about the looming rollback of Title 42, another Trump-era immigration policy that is set to expire in May.

“It’s not a surprise to me that the Biden administration has taken a rightward shift,” says Brad Jones, an immigration policy expert at the University of California, Davis. Once Title 42 lifts, “we’re going to see an increase [of migrants] like we’ve never seen before. ... I think the Biden administration is really scrambling as to what to do.”

Family detentions? Why Biden is tacking right on immigration.

On the campaign trail, then-candidate Joe Biden promised to reform the country’s immigration system by undoing many of the policies put in place by former President Donald Trump. It is possible to have a “fair and just” system that reflects America’s values and welcomes migrant families, Mr. Biden argued.

Now, more than two years into President Biden’s term, his administration is reportedly considering reinstating the practice of detaining families that cross the U.S. border illegally – a policy Mr. Biden previously criticized and that his administration had largely ended, transitioning three family detention centers into facilities for single adults. The Department of Homeland Security has been relying on alternative approaches for families, such as allowing them to enter the country with ankle monitors or other tracking devices while their immigration cases move forward.

While family detentions became a controversial focal point of the Trump administration, the policy predates the Republican president. The South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley – the largest detention center in the country – actually opened under former President Barack Obama.

President Biden’s potential policy reversal on family detentions suggests that he, like many of his predecessors, is struggling with how to balance order with compassion at the U.S.-Mexico border. Particularly when it comes to children.

The 2022 fiscal year set a record for migrant encounters, with more than 2.7 million documented nationwide, according to data from Customs and Border Protection, although the number of unique individuals apprehended is almost certainly less because some migrants attempt the crossing multiple times.

These spikes have come at a time when migration is up globally, says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy director at the American Immigration Council. As Central Americans flee authoritarian regimes and living conditions that have only further deteriorated during the COVID-19 pandemic, more migrants have headed for the U.S.-Mexico border. The record numbers seen in 2022 can be attributed in large part to asylum-seekers from Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua.

Some experts say President Biden’s pro-immigration rhetoric could also have played a factor, with migrants expecting an easier time at the border than during the Trump administration. “It is clear that many migrants perceived there to be a greater shift in U.S. policy than there actually was,” says Mr. Reichlin-Melnick.

Early statistics for fiscal year 2023 suggested it was on track to surpass the previous year. But these figures dropped sharply in January, following an announcement by Mr. Biden that Nicaraguans, Haitians, and Cubans who irregularly cross the U.S. border will be expelled to Mexico and ineligible for a new parole process, similar to the policy in place for Venezuelans. The move was criticized by groups like Human Rights Watch, which characterized the Biden administration as “reviving abusive Trump-era policies.”

Many experts say the recent shift reflects growing concerns in the administration about the looming rollback of Title 42, another Trump-era immigration policy that is set to expire.

“It’s not a surprise to me that the Biden administration has taken a rightward shift in its policies,” says Brad Jones, an immigration policy expert at the University of California, Davis. “Once Title 42 lifts ... we’re going to see an increase [of migrants] like we’ve never seen before. Right now, I think the Biden administration is really scrambling as to what to do.”

What is Title 42?

As with family detention, Mr. Biden campaigned on ending Title 42, a public health emergency order invoked by Mr. Trump at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. The order allows Border Patrol agents to turn away migrants seeking asylum without hearing their claims, which critics argue violates U.S. law. By January 2023, more than 2.6 million migrants had been expelled under this rule.

Unaccompanied children, however, can’t be expelled under Title 42 due to a federal judge’s order in late 2020. This exception, along with worsening economic struggles at home, led many parents to make the difficult decision to send their children across the border alone. Border Patrol encountered almost 147,000 unaccompanied minors in 2021 and more than 152,000 in 2022 – more than double the rates of previous years. And while the Department of Health and Human Services is required to monitor these children after they are released to sponsors within the United States, an overloaded system has led to serious lapses. A recent New York Times investigation found that many unaccompanied minors have wound up working dangerous jobs in violation of child labor laws.

The Biden administration first attempted to repeal Title 42 in April 2022, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the policy was “no longer necessary” for public health. Already, at that point, critics were suggesting the measure had little to do with public health and that the administration was simply reluctant to repeal it amid record numbers at the border.

“[The administration] is using Title 42 as a crutch,” says Tara Watson, an economics and immigration expert at the Brookings Institution. “We already have this big backlog and people are still coming. ... But instead of fixing that problem, which will take a while, they are using a stopgap, this not-ideal measure, to try and control things at the border.”

After the CDC’s April announcement, a federal judge blocked the Biden administration’s efforts to end the policy. The case has been moving through the courts ever since, even making its way to the Supreme Court.

But the Supreme Court removed the case from its docket, following the Biden administration’s announcement that the COVID-19 public health emergency will expire on May 11.

What’s next?

The news about a potential revival of the family detention policy may serve as a preemptive deterrent for migrants considering coming to the border following the end of Title 42 on May 11, say experts.

And while some argue the Biden administration should already have laid out a post-Title 42 plan, there are still measures the administration could take over the next two months. Dr. Jones, for example, suggests increasing the number of shelters at the border and connecting local governments with nongovernmental organizations that can provide assistance.

Others say Congress should take this moment as further evidence that the nation’s immigration system – which hasn’t seen comprehensive policy reform in more than two decades – is broken and needs to be urgently addressed.

“Congress can make laws that are long-standing, versus what happens when the administration switches and the whole policy switches. It’s terrible for immigrants; it’s terrible for the American people,” says Dr. Watson. “If you just give people hope that there is a pathway ... people might not just show up at the border, because there is a better way.”

Still, she and others agree that any real systemic reform seems highly unlikely anytime soon, given how divisive the politics of immigration have become – and the reality of an election cycle that’s already ramping up. While there may be some small measures with bipartisan support that Congress could agree on, “I don’t think there is hope for comprehensive reform in the immediate future,” says Dr. Watson.

Seniors and migrants in Sweden share houses, build bridges

Living situations can be difficult for seniors and for immigrants, due to loneliness and separation from society. One Swedish housing project is trying to help both groups by putting them together – and it seems to be working.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Intergenerational living projects exist around the world, but the Sällbo project in Helsingborg, Sweden, stands out for its integration of migrants. The six-story building with 51 apartments helps counter both the loneliness of advanced-age Swedes and integration difficulties faced by young migrants who arrived from places like the Middle East or Afghanistan.

Tenants of Sällbo have found common ground, which they attribute to the cumulative impact of courtesy, kindness, mutual curiosity, and understanding.

“The whole goal was to show that even if you are different and even if you are people who would not usually socialize,” says project manager Dragana Curovic, “you would do so if there is a safe environment.”

Tenants must agree to socialize at least two hours per week. That can happen in shared kitchens, activity rooms, or cozy living areas. Young and old concur that the pandemic helped strengthen the bonds that bind them. The younger residents did grocery shopping for the elders, who returned the favor by helping the young with their classes online.

“People try to understand each other,” Afghan native Zia Sarwary says. “I know you have your differences. I have mine. But we can meet in the middle ground and do something together that is good for both of us.”

Seniors and migrants in Sweden share houses, build bridges

It was when his older Swedish neighbors threw him a high school graduation party that Afghan native Zia Sarwary finally felt a sense of belonging in this picturesque seaside city.

“It meant everything to me,” says Mr. Sarwary, who at the age of 13 arrived alone in Sweden during the 2015 refugee crisis. “That was the beginning of feeling at home.”

Mr. Sarwary is one of dozens of tenants living in Sällbo, a shared-living project mixing elder Swedes and young adults, some of them from Sweden, others – like him – from the Middle East or Afghanistan. The six-story building with 51 apartments helps counter both the loneliness of advanced-age Swedes and the integration difficulties facing migrants who arrived as unaccompanied minors.

Tenants of Sällbo have found common ground within these colorful walls, which they attribute to the cumulative impact of courtesy, kindness, mutual curiosity, and understanding.

“The whole goal was to show that even if you are different and even if you are people who would not usually socialize, you would do so if there is a safe environment where you know who is in the house,” says Dragana Curovic, the project manager for Sällbo. “After three years, we can say that it worked.”

“We can meet in the middle ground”

Had they not moved under the same roof, the older Swedes and young migrants living here would almost certainly not have mingled. Fear and misunderstanding would have been major obstacles. Older Swedes’ impressions of young migrants draw heavily on negative press reports linking them to crime.

As for the immigrants, their interactions with Swedes had largely been limited to asylum center officials – authority figures who set the initial tone for the newcomers’ experience, but weren’t focused on building bonds with them.

Sällbo attempts to overcome that by getting tenants engaged with each other. To move in, tenants must agree to socialize at least two hours per week. That can happen in shared kitchens, activity rooms, or cozy living areas. Each floor boasts three common areas, ranging from puzzle and scrapbooking rooms to libraries and film-screening rooms to carpentry workshops. Sun-kissed kitchens are set up for mingling, growing herbs, pickling, and baking. Artwork decorates the hallways.

Intergenerational living projects exist around the world, but the one at Sällbo stands out for its integration of migrants. Young and old concur that the pandemic helped strengthen the bonds that bind them. Younger residents did grocery shopping for the elders, who returned the favor by helping those with low computer skills keep up with their classes online.

Now a logger working night shifts, Mr. Sarwary wishes he had even more time to spend with his older neighbors and feels bad when he needs to cut conversations short to catch his bus. After all, elders are treated with deference in Afghanistan. He believes curiosity feeds residents’ capacity to find common ground across cultures and age groups.

“People try to understand each other,” he says. “I know you have your differences. I have mine. But we can meet in the middle ground and do something together that is good for both of us. There is a positivity in everything. That is the best part.”

“Sometimes you do things that are not correct,” Mr. Sawary continues. “Instead of people coming in scolding you, they come in and they’re like, ‘Oh, you could do it this way.’” That attitude manifests itself in small tasks he performs, such as helping an older resident change a lightbulb, and in longer endeavors such as a neighbor teaching him how to drive.

It helps that people understand that he had a tough background and approach him with an open mind to learn about his headline-grabbing, war-torn homeland.

“They would always ask instead of just judging. ‘OK, is this true about your country?’” he says. “Even now they ask [questions] here in Sällbo. Everywhere else they don’t even ask. They have this picture in their head about you. ... In Sällbo, what I like is that they are very curious.”

“I love the young kids”

Jan Gustavsson, a retired provider of security systems, says he like helping young people from Afghanistan and other parts of the world integrate. “We can see in other places where no one does anything, there’s a lot of crime,” he says. “Like in Stockholm and Gothenburg, there’s a lot of problems with them.”

“I think it will help if these people live together with Swedish people,” he adds. “They learn more about the Swedish customs and traditions. They get to know other people. Their Swedish improves.”

Anki Andersson oversees scrapbooking activities on Tuesdays. Her husband, Kalle, helps fellow seniors do seated workouts. “Sällbo is the perfect place if you are mobile and seeking to socialize,” says Ms. Andersson. “People here are so alike in a way. It is hard to explain. We click together very well, both the older and young residents.”

“They were very helpful during the pandemic, but also before and after,” she says of the young people. “If we have something we need to do or heavy things to carry, they give as a hand. We are a big family.”

Retired schoolteacher Gunilla Olsson feels especially at home. She is still touched that one of the girls studying to become a doctor brought her chocolate. It was a gesture of thanks to her for always saying good night as she passed the study on her way to her apartment every night.

“I love the young kids,” says Ms. Olsson “It’s so good to have them around with their smiles. It is so good for old people to be around young people.”

“I love the different ages and cultures,” concurs Ritva Gustafsson, a retired Swedish language teacher. “I love it because they are still looking forward to something. We have things behind us so we can bring them something. And they can bring us something. It is very exciting to share the experiences of their home countries.”

Conversations can turn political and ethical, she notes. But even amid differences of opinion, they do not turn as heated as they might at a family dinner table. “When people are discussing values, when something happens, they put forward what they think and why they think it,” she says. “There is respect.”

The biggest trigger for low-level shared living conflict? “Fluff,” says Sonja Håkansson, who oversees the building. “Laundry fluff and dishes.”

The project “has worked better than I thought it would,” she says. “Having so many different personalities and different ages from other cultures, I thought that was going to be a bigger issue. But people find their similarities.”

“We are interlinked”

Safety is central to the smooth functioning of the building. Guests are allowed – and can even stay overnight in a room set aside for visitors – but must always be accompanied by their host. The night lights are always on. Each floor has its own cheerful color scheme to make it easier for aging people to find their bearings.

But the real safety comes from knowing each other and watching out for each other. Neighbors are quick to notice when someone is not around or has fallen ill. “You can always knock on someone’s door,” says Ms. Gustafsson.

Amel Ben Jmaj, a biotech student from Tunisia, is one of the newest tenants and already loves the place. She recently moved in to join her fiancé, a construction worker, and is awaiting her Swedish residency permit.

“It is a completely different way of living,” she says, finishing up the dishes as she makes plans to make baklava for an upcoming party. “We are interlinked. We play puzzles together, watch films, and throw parties. It’s heaven.”

Editor’s note: Dates on some photographs have been corrected to read “2023.”

On film: How a pinball wizard fought the law, and won

What do people do when they encounter well-intentioned laws they disagree with? A pair of filmmaking brothers found a message about freedom in the story of the man who helped legalize pinball.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Pinball was once illegal in many cities – seen as a hotbed of immorality and a front for the mob. In New York, police confiscated and destroyed pinball machines in Prohibition-like raids. Authorities declared them games of chance and thus a form of gambling.

In 1976, an unlikely champion emerged: a writer for GQ magazine named Roger Sharpe. In a bold gambit to change New York’s law, Mr. Sharpe set up two pinball machines inside City Hall. He had one shot to demonstrate to city council members that it’s a game of skill.

“Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game,” written and directed by brothers Austin and Meredith Bragg, is based on this true story. It’s a classic tale about the little guy standing up against an unjust system. The film, available March 17, is also about the two loves of Mr. Sharpe’s life: his budding romance with the woman who became his wife, and his obsession with the venerable arcade game.

“There are risks in life, and you either take those risks or you don’t,” he says during a Zoom call. “Many of us tend to feel self-doubt when we venture down a path. So I’d like to believe that one of the [lessons] is believe in yourself and reach for your stars.”

On film: How a pinball wizard fought the law, and won

When Austin and Meredith Bragg co-directed their first movie, the brothers learned something that isn’t taught at film school.

“The old adage is, in film, don’t work with animals and children. You can add pinball machines to the list,” says Austin Bragg, shivering slightly while sitting next to his older brother at an outdoor cafe in New York on a chilly February afternoon. “They are notoriously difficult, especially those old electromechanical machines.”

The brothers’ debut feature film, “Pinball: The Man Who Saved the Game,” is based on a true story about trouble with a capital T, and that rhymes with P and that stands for pinball. The game was once illegal in many cities – seen as a hotbed of immorality and a front for the mob. Here in New York, police confiscated and destroyed pinball machines in Prohibition-like raids. Authorities declared them games of chance and thus a form of gambling.

In 1976, an unlikely hero emerged to champion the game: a writer for GQ magazine named Roger Sharpe. The often-comedic “Pinball,” available in select theaters and to stream starting March 17, is about the two great loves of Mr. Sharpe’s life. It recounts the writer’s budding romance with the woman who became his wife. It’s also about his obsession with the venerable arcade game. In a bold gambit to change New York’s law, Mr. Sharpe set up two pinball machines inside City Hall. He had one shot to demonstrate to city council members that it’s a game of skill. The movie is a classic story about the little guy standing up against an unjust system.

“It was just a pure joy to watch. It’s one of those movies that you immediately want to tell your family and friends about,” says Julia Ricci, senior programmer of the Heartland International Film Festival in Indianapolis, where “Pinball” won the 2022 Audience Choice Award. “We’re looking for films that do basically just more than just entertain, whether they can inspire, uplift, educate, inform, or shift perspectives.”

“Pinball,” written and directed by the Braggs, is stylized as a faux documentary. An older version of Mr. Sharpe (portrayed by Dennis Boutsikaris from “Better Call Saul”) talks to an off-screen interviewer. Most of the movie consists of reenacted scenes of the younger version of Mr. Sharpe (played by Mike Faist from the 2021 remake of “West Side Story”).

The first words of dialogue in the movie were inspired by the Bragg Brothers’ initial phone conversation with the real Roger Sharpe.

“I still remember talking to him and saying, Roger, I’m going to open this movie with you saying, ‘I don’t know why you want to make this a movie,’” says Austin Bragg.

For his part, Mr. Sharpe was worried that a feature film was going to consist of nonstop pinball playing. Many hours of open-hearted conversation with the filmmakers yielded a richer story about a pivotal point in Mr. Sharpe’s life. After a failed first marriage and a layoff from an advertising firm, he was trying to reinvent himself. He embarked on a writing career and became romantically involved with a divorced woman named Ellen, who had a son.

“There are risks in life, and you either take those risks or you don’t,” says Mr. Sharpe during a Zoom call. “Many of us tend to feel self-doubt when we venture down a path. So I’d like to believe that one of the [lessons] is believe in yourself and reach for your stars. Hopefully there is some form and measure of inspiration from my character but, more importantly, from someone like Ellen.”

The most important storyline of the movie, he adds, is “the empowerment of a single mother.” His wife (played by Crystal Reed from TV’s “Teen Wolf”) later opened up her own art studio.

If that sounds pretty far afield from pinball, there’s also a concurrent storyline about Mr. Sharpe’s obsession with the arcade game. (As befits a pinball wizard, he has a much-remarked-upon mustache that is as wide as the lapels of a 1970s polyester suit.) He started researching a book about the history of pinball, a game that became popular during the Great Depression. But after Mayor Fiorello La Guardia of New York banned pinball in 1942, cities such as Chicago, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, and New Orleans followed suit.

“Having had the chance to have met so many of the people who helped shape the industry, and realizing that they were all really good people, the condemnation of them was truly not warranted,” says Mr. Sharpe.

Austin and Meredith Bragg have long been interested in well-intentioned laws that backfire. The brothers are award-winning video journalists for the libertarian-leaning Reason magazine. But before that, the Braggs got their start at a public access TV station in Arlington, Virginia, where they produced an amateur superhero series.

“That was sort of our first film school, just learning how to do this,” says Meredith Bragg.

Their early adventures in “no budget” filmmaking honed their ability to quickly adapt to changing circumstances. So when a ceiling fan at the cable access station caught fire while they were filming at 2 a.m., the Braggs improvised an action sequence. When firefighters arrived, they were bewildered to find the blaze had already been extinguished by someone painted blue from head to toe.

In their spare time, the duo created a series of award-winning short movies. The Braggs’ 12-minute film, “A Piece of Cake,” premiered at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival. It’s about a California man who tries to buy tiny decorative silver balls for his daughter’s birthday cake. He discovers that the dragée balls are only available via the state’s underground economy. Legal woes ensue.

“Our worldview is based on a desire to maximize choice for people,” says Meredith Bragg. “Sometimes systems are unjust, and sometimes they’re impersonal. Allowing people to pursue their idea of happiness, even if it seems to be something trivial, like a dragée or pinball, I think is important.”

Encouraged by the success of “A Piece of Cake,” the Braggs embarked upon their feature about a different kind of silver ball. Produced by the Moving Picture Institute, whose mission is to create “captivating stories about human freedom,” “Pinball” featured a bigger budget than anything the Braggs had worked with. (Among the expense items: two fake mustaches for Mr. Faist.) When Mr. Sharpe visited the set, he was struck by the brothers’ assured approach as they sculpted the details of each scene.

“I believe they have an incredibly brilliant future ahead of them,” he says.

Mr. Sharpe was also called upon to execute some of the tricky pinball shots, jostling the sides of the machine and flicking the metal ball precisely from one pinging target to the next. The film’s end credits include a humorous disclaimer: “No pinball machines were harmed during the making of this movie.”

Mr. Sharpe is helping promote the movie at several screenings, including one in South Carolina, where aficionados are campaigning to overturn a long-term ban on children playing the game.

“People trying to do good cause a lot of unintentional harm,” says Austin Bragg. “It may sound like a good idea to ban pinball for the kids or whatnot, but in the end, you just end up hurting more people than you realize.”

His brother adds, “I love the idea of Roger yet again freeing pinball from absurd laws.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A bottom-up approach to authentic peace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The world’s conflicts often end with top-down solutions, such as diplomatic agreements. Yet nearly half of post-conflict places return to violence within a decade. Often overlooked are bottom-up attempts at peacemaking, the kind that lay the groundwork for permanent peace. Two examples came this week from Israel and Libya.

After a Palestinian assailant killed two of her children, Orthodox Jew Dvori Paley asked a large group of women, “What can we do so that we don’t experience this anymore?” The answer, arranged by a friend of hers, was to open the living rooms of 40 homes for women of all walks of life to do what Ms. Paley wished – expressions of gratitude for the good in daily life.

In strife-torn Libya, peace is being built in part through youthful creativity. At an event outside Tripoli, about 20 teams of young people from all social strata competed in their designs of robots. “These young people also had to ... work towards inclusion, unity, and peace,” said the event coordinator.

“Being in turbulent settings, many peace builders mention the need for an inner stillness,” writes author Tobias Jones. That can come from gratitude meet-ups or the rapture of a robot-making contest or any manner of local encounters that can help define peaceful coexistence.

A bottom-up approach to authentic peace

The world’s violent conflicts often end with top-down solutions, such as diplomatic agreements or a peace imposed by military might. Yet nearly half of post-conflict places return to violence within a decade. Often overlooked are local, bottom-up attempts at peacemaking, the kind that can collectively lay the groundwork for permanent peace. Two examples came this week from Israel and Libya.

After a Palestinian assailant killed two of her children, Orthodox Jew Dvori Paley asked a large group of Israeli women, “What can we do so that we don’t experience this anymore?” The answer, arranged by a friend of hers, was to open the living rooms of 40 homes for women of all walks of life to do what Ms. Paley wished – expressions of gratitude for the good in daily life.

“The point is to show people that we are all part of something bigger,” said Ayellet Ben Zaken, a literature teacher.

These gatherings for thankfulness have since spread beyond Israel, according to a news story by Media Line. “Dvori quickly became a symbol for many, crossing boundaries that very often exist in society,” it stated.

In strife-torn Libya, peace is being built in part through youthful creativity. At an event outside Tripoli this month, about 20 teams of young people from all social strata competed in their designs of robots. The high-tech contest, however, was not just about robots.

“These young people also had to manage their relationships and work towards inclusion, unity, and peace,” event coordinator Mohammed Zayed told Agence France-Presse.

As one participant, Youssef Jira, said, “We want to send a message to the whole of society, because what we’ve learned has changed us a lot.”

These small platoons of local peacemakers usually don’t show up in today’s quantitative measurements of peace. The famed Global Peace Index, for example, looks at macro numbers, such as levels of military spending or crime levels. The Fragile States Index looks at indicators such as “group grievance” or “state legitimacy.”

A couple of new peace quantifiers are taking a different approach. The nonprofit group Search for Common Ground is working on a “peace impact framework” based on asking local people for their knowledge and experience from living in a conflict to determine indicators for peace. The new Community-Based Heritage Indicators for Peace relies on local people for “their own nuanced understanding of what lasting peace looks and feels like on-the-ground.”

This listen-first approach rests on the assumption that peace can come from each person’s natural inclination for peace.

“Being in turbulent settings, many peace builders mention the need for an inner stillness,” writes author Tobias Jones for Aeon journal, a process that requires making peace with oneself and only then with others. That can come from gratitude meet-ups or the shared rapture of a robot-making contest or any manner of local encounters that can help define authentic peaceful coexistence.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Family that’s whole, harmonious, and happy

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

When the warmth of family feels elusive, we can find wholeness and comfort in cherishing God as our Father-Mother and friend.

Family that’s whole, harmonious, and happy

Sometimes it can feel as if happy families only exist in fairy tales. It may even seem normal to feel isolated and lonely, or troubled in our close relationships. But even when challenges feel insurmountable, many people have found that a spiritual sense of themselves and others has a healing impact on their experience of family.

Here’s a selection of articles from the archives of The Christian Science Publishing Society that bring forward this God-centered approach to family – one that isn’t contingent on person or place for love, comfort, and home to shine through. Wherever we are, whomever we are with, a growing understanding of our relation to God can help us find a complete and holy family experience.

“The bedrock of meaningful relationships” explores the strong spiritual foundation that empowers us to build lasting connections.

In “Our ‘Gen 1’ heritage,” the author shares how claiming her true heritage as a daughter of God, with a purely spiritual origin and identity, empowered her to drop the baggage of troubled family history.

In “Inspired Bible study defeats depression,” a father who had unexpectedly lost access to his children shares how relationships with them were renewed as a result of spiritual growth, illustrating the enduring power of the Bible’s promises.

The author of “‘All tears will be wiped away’” tells how embracing a spiritual view of her dad – one that never dies – helped her overcome devastation after her dad passed on.

In “‘Is that your job?’ A question sparks healing at Christmastime,” a woman explores the concept of peacemaking as Jesus expressed it – less about stress and more about trusting God – which helped her navigate a contentious situation between family members.

Disappointed when she and her husband found they couldn’t have children, a woman turned to ideas that brought inspiration, peace, and fulfillment, which she shares in “What I’ve learned about family.”

Viewfinder

Ide watch that

A look ahead

Thanks for spending time with us today. For more on what happened today as concerns about banks mounted around the world, please click here. And tomorrow, we'll lead off with a look at how economic officials now face a clash of values: How to balance fighting inflation against preventing bank failures – and why it matters.