- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A big change to our website

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Since 1908, the Monitor has been about exploring deeper themes and ideas. Since last summer, we’ve been working to make that even plainer. For many of our stories, we’ve been identifying the deeper values that drive the news, such as justice, generosity, resilience, and so on.

On our website, our News & Values page shows all the values we chart and all the stories we’ve done about them. Now, we’re adding a new way to navigate CSMonitor.com. This will make it easier to find news by topic and region, but also now by value, as well.

Why is this important? We know people are exhausted by the constant drumbeat of pessimism, fear, anger, and disrespect. The answer is not in simply talking about policies and news events more kindly. Or in just looking for the good news. And it doesn’t mean going left or right.

It means going deeper into what really matters. News is not just about events. It’s the story of how humanity is wrestling with deeper demands – to be more just, more compassionate, to spread safety and prosperity. When we go beyond the headlines, we find the place where news can begin to unite instead of divide, can be constructive rather than demoralizing.

There’s more work for us to do, both in our journalism and in our products. But making our site navigation easier is an important step toward making it clearer to the world how journalism can be different – and better.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

With credibility at stake, Fed fires new volley at inflation

The Federal Reserve’s credibility as an inflation fighter is on the line. Fed Chair Jerome Powell signaled his resolve on that today, with an interest rate hike despite recent U.S. banking troubles.

Having spent the past year single-mindedly fighting inflation, America’s central bank now faces a dilemma. Its inflation fight may be triggering an equally big problem: a recession in the United States.

If Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell can bring down inflation and avoid a deep recession, he will have successfully negotiated a rough passage for the economy. But if his inflation battle proves ineffective, he will further damage the Fed’s credibility, which is already tarnished by a surge in inflation last year.

“Credibility is important for everybody, but central banks especially, because their prime function over the centuries has been to preserve the value of money,” says Michael Bordo, an economic historian at Rutgers. “And when that gets eroded, that is terrible.”

On Wednesday, the Fed acknowledged the leadership challenge. It stuck to its inflation-fighting mandate, hiking a key bank lending rate by a quarter of a percentage point and bringing interest rates to their highest level since 2007, the eve of the Great Recession.

But it also signaled that those rate hikes could be coming to an end. That will happen only when it’s clear that inflation is declining across most economic sectors, Mr. Powell said at a press conference Wednesday.

With credibility at stake, Fed fires new volley at inflation

Having spent the past year single-mindedly fighting inflation, America’s central bank now faces a dilemma. Its inflation fight may be triggering an equally big problem: a recession in the United States.

If Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell can bring down inflation and avoid a deep recession, he will have successfully negotiated a rough passage for the economy. But if his inflation battle proves ineffective, he will further damage the Fed’s credibility, which is already tarnished with costly mistakes last year.

“Credibility is important for everybody, but central banks especially, because their prime function over the centuries has been to preserve the value of money,” says Michael Bordo, an economic historian at Rutgers in New Brunswick, New Jersey. “And when that gets eroded, that is terrible.”

On Wednesday, the Fed acknowledged the leadership challenge it faces. It stuck to its inflation-fighting mandate, hiking a key bank lending rate by a quarter of a percentage point, bringing interest rates to their highest level since 2007, the eve of the Great Recession. But it also signaled that those rate hikes could be coming to an end. Its post-meeting statement referred to the possibility of “some additional firming” of rates, as opposed to previous statements’ references to “ongoing increases.”

In essence, the central bank is preparing financial markets and the public for a future pivot point where it stops fighting inflation and either takes a neutral stance or starts to support a weakening economy. But that time is not yet.

“We have to bring inflation down to 2%,” Mr. Powell said at a press conference Wednesday. “There are real costs to bring about 2% [inflation], but the costs of failing are much higher. ... You can have a long series of years where inflation is high and volatile and it’s hard to invest capital. It’s hard for an economy to perform well.”

Mr. Powell and the Fed missed the boat when inflation began to rise two years ago, many economists say. At the time, the Fed argued the jump in prices was temporary, driven by pandemic-related supply chain shortages rather than an increase in demand. After a costly year of inaction in which headline inflation surged to 40-year highs, the Fed finally made a U-turn almost exactly a year ago and began to raise interest rates in a bid to slow the economy and bring inflation down. Wednesday’s move, though smaller than the half-point hike that had been widely expected until recently, marks the ninth rate hike in the past year.

A test for Powell

Mr. Powell’s single-minded aggressiveness has helped rebuild his reputation. “I have never been a big fan” of the Fed chair, says Charles Calomiris, a Columbia Business School professor and former chief economist of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. “But you know, I’ve been impressed that he’s actually been fairly straight. He’s actually been honest about his mandate to maintain a long-term inflation target.”

That stick-to-it quality may be sorely tested now that the economy is looking increasingly fragile, especially in the tech and banking sectors. Vulnerable industries typically wobble as interest rates rise, making it more expensive to take out new loans and service some forms of existing debt. Such periods call for extremely fine judgment.

Raise rates too high and the economy sinks into a deep recession. Stop raising rates too early and the U.S. could get something even worse: a slow-growth economy with inflation that stays stubbornly high, a condition known as stagflation. After such an episode in the 1970s, the Fed under Chair Paul Volcker raised rates to 20%, sending the economy into a deep recession but inaugurating a quarter century of low-inflation growth.

These periods – when curbing inflation can impose short-term hardship on the economy – also give rise to growing industry and political criticism of the Fed. “It takes a certain amount of courage to be able to go against the pressures that are coming from the Congress and the financial markets,” says Mr. Bordo of Rutgers.

In another sense, however, this period of perceived economic vulnerability helps the Fed. If markets and businesses believe that the Fed is going to do what it said it would do, then typically banks and other lenders grow cautious and start to turn away borrowers or charge them more for taking out loans. Companies delay plans for expansion and begin to lay off workers. These moves, in essence, do the Fed’s work by slowing the economy without the central bank having to boost rates further.

In recent days, economists have tried to predict the effects of such private-sector moves, suggesting they might slow the economy by the same amount as a Fed interest rate hike of anywhere between 0.5 and 1.5 percentage points.

“The events of the last two weeks are likely to result in some tightening credit conditions for households and businesses,” Mr. Powell said at the press conference. “The question is, how significant will this credit tightening be and how sustainable?”

Bank troubles to address

One of the big concerns is that a Fed-engineered slowdown could trigger a banking crisis. The collapse of two banks earlier this month has set off a wave of worries that other banks will fail.

“The core of what crisis-fighting requires is speed, flexibility, and clout,” says Robert Bruner, a professor of business administration at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville and co-author of “The Panic of 1907.” “You really have to intervene fast.” So far, he’s cautiously optimistic that regulators can contain the fears.

Although regulators weren’t able to prevent an old-fashioned run from collapsing one of the failed banks, the Fed along with the U.S. Treasury and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. did step in afterward to avoid similar problems elsewhere. The regulators used a special provision to bail out all the failed banks’ depositors, even those with more than the maximum insured by the FDIC, and loans to the banks for bonds at their par value rather than their diminished market value.

U.S. bankers are working on backstopping First Republic, whose shares have dropped nearly 90% this month. And on Sunday, the Swiss government engineered the buyout of long-troubled Credit Suisse by that nation’s largest bank, UBS.

“You need a good story”

Mr. Powell also has some room for maneuvering, says Pierre Siklos, an economics professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario. As Fed chair, he has the power not only to act but also to shape public expectations through what he says.

“You need a good story, a story that’s believable to the financial analysts – those who are experts – and the general public; [then] they can say, ‘Yeah, that makes sense,’” he says. “The language that you use and the story that you provide are critical.”

That’s what President Franklin Roosevelt did in his first fireside chat, a few days after his inauguration, when he told Americans what he was doing to end the bank runs of the Great Depression, says Andrew Metrick, director of the Yale Program on Financial Stability and former chief economist at the White House Council of Economic Advisers. It’s what Mario Draghi, as head of the European Central Bank, did in 2012 when in the midst of a currency crisis he uttered the now-famous words: “The ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

Both men soothed fears and solved the financial problems of their day, says Mr. Metrick. “Just be as clear as possible about what it is that the government can and will do, and do it in a credible way.”

Ultimately, though, Mr. Powell’s leadership may be judged by how well his words match the economy’s performance, says Mr. Bordo of Rutgers. “The only way Powell is going to come out of this looking good is if they pull it off – in other words, if we don’t have a recession or it’s a mild one and inflation goes down to 2% and we don’t have a huge banking panic.”

How Ukraine war has tightened Russia-China bond

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin’s summit in Moscow was nominally meant to be about bringing peace to Ukraine. But it appears to have strengthened the countries’ partnership against the West.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The summit between Chinese leader Xi Jinping and his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, ended Wednesday with little publicly announced progress toward peace in Ukraine. But what did become clear is that the intense geopolitical pressures triggered by the war have driven Russia and China closer together.

The two leaders spent hours in closed, personal talks and signed a raft of new agreements aimed at cementing a strategic partnership that has been tightening for years. The deals included stepped-up military coordination, expanded trade, and a “nearly finalized” compact to build a major new gas pipeline.

Whether or not China plays peacemaker, a potentially more important byproduct of the war in Ukraine is to cement Russo-Chinese bonds. The two countries’ burgeoning relationship is mostly driven by their mutual alienation from the West, and by the need to have each other’s back if the East-West confrontation escalates.

“The really new thing here is that the Chinese appear to have concluded that their relations with the U.S. are headed for full confrontation, if not conflict,” says Dmitry Suslov, a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “The understanding has dawned that the Russia-China partnership makes each stronger vis-à-vis the U.S.”

How Ukraine war has tightened Russia-China bond

When Chinese leader Xi Jinping arrived in Moscow on Monday for a three-day summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin, one of the most talked about items on their agenda was a Chinese-mediated settlement for the war in Ukraine.

As Mr. Xi’s plane departed on Wednesday, though prospects were discussed and Mr. Putin lauded a 12-point Chinese list of principles for establishing peace, no specific progress publicly emerged.

But what did become clear is that the intense geopolitical pressures triggered by the war have driven Russia and China closer together.

The two leaders spent hours in closed, personal talks and signed a raft of new agreements aimed at cementing a strategic partnership that has been tightening for years. The deals included stepped-up military coordination, expanded trade, a “nearly finalized” compact to build a major new gas pipeline that would permanently divert Russian gas supplies from Europe to China, and more concerted efforts to remove the U.S. dollar from their mutual economic transactions.

Whether or not China plays peacemaker – which Russian commentators say is not likely to be a possibility until after further developments occur on the battlefield – a potentially more important byproduct of the war in Ukraine is to cement Russo-Chinese bonds. The two countries’ burgeoning relationship is mostly driven by their mutual alienation from the West – and from the United States in particular – and by the need to have each other’s back if the East-West confrontation escalates.

“The really new thing here is that the Chinese appear to have concluded that their relations with the U.S. are headed for full confrontation, if not conflict. That was not obvious even at the beginning of the Biden administration, but now it is. Things are getting worse and worse,” says Dmitry Suslov, a professor at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “The understanding has dawned that the Russia-China partnership makes each stronger vis-à-vis the U.S., that consolidating this partnership is an existential issue for both.”

“China as a truly global player”

Last month, the Chinese Foreign Ministry published a hefty indictment of “US Hegemony and its Perils,” which spells out a list of historical grievances and a manifesto for a new multipolar world order that dovetails very neatly with the Kremlin’s thinking.

“Hence, the economic and strategic partnership [that Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin] are forging is not merely mutually beneficial,” Mr. Suslov says. “In every area, from agriculture to finance, we see that China and Russia are pledging to supply each other with the critical resources necessary for survival. Even if we should find ourselves in a situation of complete economic blockade, we will be able to help each other deal with the challenges.”

Another new factor is that any uncertainty about who will be leading China for the foreseeable future has been dispelled with Mr. Xi’s reelection to an unprecedented third term as leader. Mr. Xi, in turn, took the extraordinary step of telling Mr. Putin publicly that he believes the Russian people will support Mr. Putin in upcoming 2024 presidential polls. The signal, Russian analysts say, is that these two leaders expect to be around for quite awhile, and are prepared to hatch serious long-range strategic plans.

“There is a whole new level to the relationship,” says Andrey Klimov, deputy head of the International Affairs Committee of the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament. “Xi is now really leader of China, and not just another general-secretary. He is ready to build a long-term strategic partnership; we are no longer talking just about the near horizon.”

Analysts say China is increasingly worried that most of its trade with the outside world passes through the Strait of Malacca, which could theoretically be cut in any conflict by the U.S. Navy. Next door Russia, with whom China shares a 2,600-mile border, is a veritable cornucopia of raw materials, energy, and undeveloped arable land. Its rail network also offers a potential link to Europe, while the Northern Sea Route over the top of Russia potentially offers a U.S. Navy-free path to the Atlantic Ocean for Chinese shipping. Russian analysts say it’s no coincidence that most of those areas, including joint development of the Arctic shipping route, were the subjects of intense discussion and many of the agreements signed during the talks.

Andrey Kortunov, academic director of the Russian International Affairs Council, which is affiliated with the Foreign Ministry, says that the consolidation of relations with Russia is a part of a broader Chinese outreach to the world, which is moving beyond the economics-led approach embodied in the Belt and Road Initiative.

“We see the Chinese becoming more active in Africa and Latin America. The so-called Chinese peace plan for Ukraine is part of this much bigger effort to position China as a truly global player, second to none,” he says. “Many people in the Global South are looking for new arrangements, and the principles outlined in that Chinese plan are broadly applicable, not just about Ukraine, but about the way the Chinese think the world should be run.”

Playing the long game

The Chinese and Russian leaders reportedly spent quite a while discussing the conflict in Ukraine, but had little of substance to say about it in their lengthy final statement.

“China would prefer to empathize with Russia in its standoff with the West, rather than openly support it in the conflict with Ukraine,” says Mr. Kortunov. “China does hope, down the road, to position itself to mediate in the war. That requires maintaining good relations with Kyiv. It should be remembered that China has big investments in Ukraine, has been a major trading partner, and would obviously also want to be a major player in any reconstruction efforts,” he says.

At the same time, there was no mention of last week’s arrest warrant for Mr. Putin, issued by the International Criminal Court, in the public record of Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin’s meetings. Mr. Suslov argues that the warrant was an attempt to influence Mr. Xi on moral grounds that proved unsuccessful. “Xi made it clear that he will not listen, much less succumb to Western pressures,” Mr. Suslov says.

No one knows whether Mr. Xi and Mr. Putin discussed any of the nuts and bolts that would be required in an eventual peace settlement such as territorial concessions, demilitarization, reparations, and neutrality status. But neither Moscow nor Kyiv seems remotely prepared for any such discussion at this point, and both are looking to future battlefield developments to set any hypothetical future negotiating table. Analysts say China is playing a long game here, and positioning itself to step in as mediator when the moment arises.

In a practical way, however, China does already provide Russia with a lot of goods that help keep its war economy running, as well as bolstering Moscow’s budget by purchasing a lot of Russian energy. The U.S. government has worried out loud that China could start providing arms to Russia – a very real concern considering that most Chinese weaponry, particularly ammunition, is derived from Soviet designs, and thus compatible with contemporary Russian systems.

Mr. Kortunov argues that, despite the very upbeat tone of the summit, China is not yet ready to completely throw in its lot with Russia.

“Much will depend on the future course of U.S.-China relations,” he says. “If they continue to deteriorate, as they are now, we can foresee the world splitting into two economic blocs. Then the logic of consolidating the full partnership with Russia will become overwhelming for China. Right now, I believe China still has strong economic interests to protect, and real hopes that, through diplomacy, a full confrontation with the U.S. can be avoided.”

Patterns

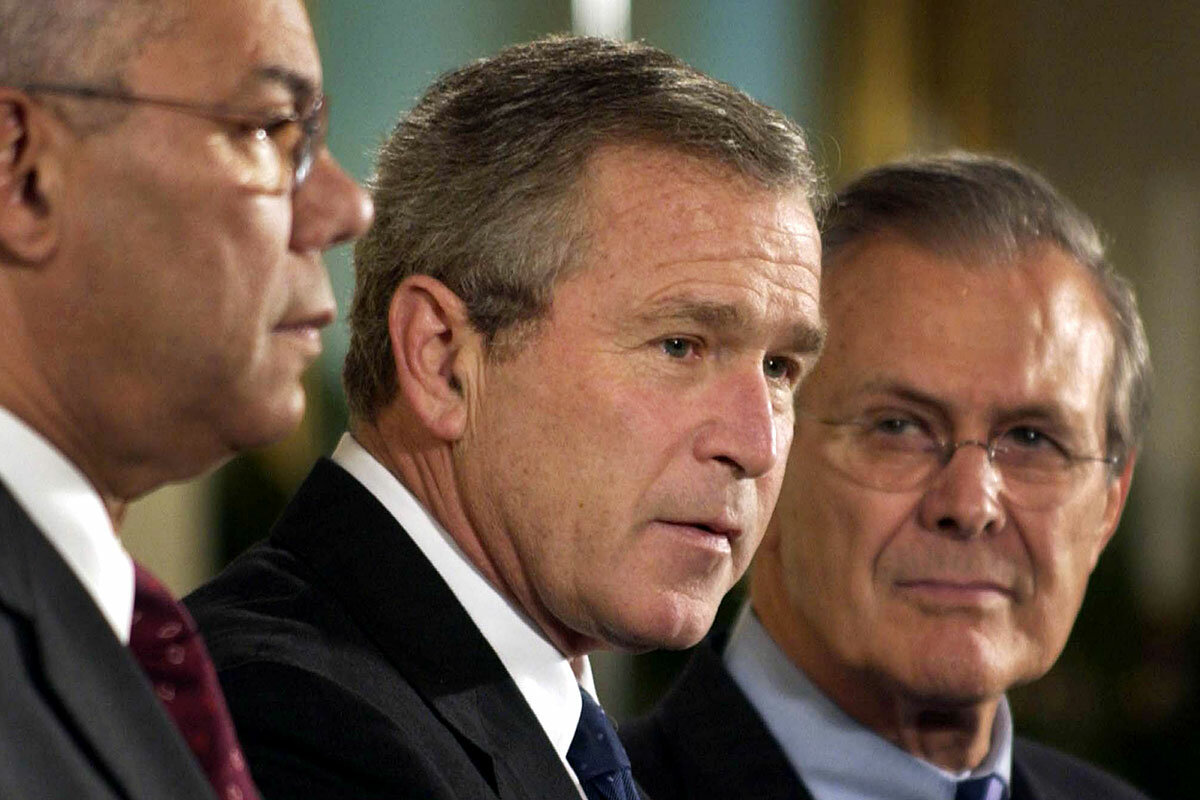

Iraq War failures color Biden policy on Ukraine

President Biden has shown in Ukraine that he has learned the lessons of the Iraq War fiasco from 20 years ago. But the U.S. role in the world remains undecided and controversial.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Twenty years on, the United States’ invasion of Iraq still casts a shadow over Washington’s foreign policy, with essential connections to the present day.

The most straightforward tie? The long shadow of the Iraq War has colored every major decision that President Joe Biden has made on Ukraine.

The multiple ways in which America’s war in Iraq went wrong have made a kind of anti-how-to-do-it guide for U.S. involvement in conflicts abroad. That was the easy lesson.

Harder are the questions that remain unresolved – about America’s power, place, role, and responsibility in the wider world. To answer them would mean revisiting a principle in international affairs that the Iraq War tarnished: the notion that nations had a right, even a duty, to intervene to protect civilian victims of war crimes.

President Biden has dodged such questions. His core justification for U.S. action over Ukraine has been that Vladimir Putin’s attack was an unprovoked assault on a neighboring country’s sovereignty. That argument has won overwhelming support at the United Nations.

Washington and London stepped back from intervening in Syria in 2013, even after Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons. It may be that the Iraq War has made even humanitarian intervention impossible now, however gross the violation of Western values.

Iraq War failures color Biden policy on Ukraine

Kyiv, 2023. Baghdad, 2003. Two very different places, engulfed in very different wars.

Yet there’s an essential connection, brought into focus this week by the 20th anniversary of America’s ultimately disastrous invasion of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

The most straightforward tie? The long shadow of the Iraq War has colored every major policy decision President Joe Biden has made on Ukraine, ever since Russian President Vladimir Putin massed more than 100,000 troops on the border ahead of last year’s invasion.

The multiple ways in which America’s war in Iraq went wrong have made the war a kind of anti-how-to-do-it guide for U.S. involvement in conflicts abroad even two decades later.

That has been the easy lesson of the war.

A tougher challenge remains: resolving fundamental questions raised by the sheer scope of then-President George W. Bush’s war in Iraq – about America’s power, place, role, and responsibility in the wider world.

Above all, that will mean revisiting a principle in international affairs that had been gathering force before the Iraq invasion. For instance, the United States and Britain had used it to justify their use of force to halt the “ethnic cleansing” and wholesale war crimes in the 1990s war pitting Yugoslav forces against Albanians in Kosovo.

It was the notion that nations had a right, even a duty, to intervene on moral grounds – an idea later echoed in the 2005 endorsement by the United Nations of a “responsibility to protect” civilian victims of such atrocities.

This was one of many strands in the decision-making process that led America to attack Iraq – a process that, as one New York Times writer has trenchantly detailed, remains opaque to this day.

So post-Iraq, is that notion, too, now part of the anti-how-to-do-it playbook? Are there still situations in which values and principles might make geographically distant conflicts a matter of America’s national interest? And can a post-Iraq president credibly make that case to voters in an increasingly divided, inward-looking America?

For now, at least, any and all aspects of the Iraq invasion seem to be a flashing red warning light.

President Biden has clearly applied the “easy lessons” in Ukraine.

He has steered clear of the direct use of American military might. In Iraq, overwhelming force – “shock and awe” – quickly defeated Saddam’s ill-matched military, but set the stage for years of violence and instability.

Mr. Biden has rebutted any suggestion that Washington is looking to force a “regime change” – not, obviously, in the allied democracy of Ukraine, but not in Russia either. The Iraq War explicitly sought to depose Saddam Hussein and, in an overweening act of geopolitical engineering, plant democracy in Iraq and transform the wider Muslim Middle East.

It ended up strengthening America’s main regional foe, Iran, as well as spawning a Sunni jihadist army, the Islamic State.

And while the Bush administration deployed intelligence reports on Saddam’s alleged chemical weapons program to justify the invasion – intelligence that turned out to be wrong – Mr. Biden has taken care to use satellite information and other equally reliable political intelligence to make the case for deliberately more limited, and calibrated, U.S. involvement in Ukraine.

Above all, while Mr. Bush went to war with just one major ally, Britain, President Biden assembled a wide coalition of European and other allies ready to hit back against a Russian invasion with unprecedentedly tough sanctions. In the months since, he has acted in close coordination with U.S. allies to provide funds and weapons for Ukraine’s resistance.

But what of the “hard” part of the Iraq legacy – the wider question of whether all forms of values-based military action should be consigned, along with the other aspects of the Iraq War, to an unlamented dustbin of history?

In Ukraine, interestingly, Mr. Biden has in effect dodged that question. Yes, he has framed the war as pitting an autocratic Russia against democratic Ukraine. But his core justification for U.S. action has been that Mr. Putin’s attack was an unprovoked assault on a neighboring country’s sovereignty in clear violation of the U.N. Charter.

It is that argument that has galvanized overwhelming opposition in the U.N. General Assembly to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Whether future U.S. or other Western leaders might revisit the doctrine that came to be known as “liberal interventionism” may depend on how willing they are to look beyond the many failures of the Iraq War and recall other recent conflicts.

Conflicts like the Kosovo War, for instance, when then-President Bill Clinton was ultimately persuaded by British Prime Minister Tony Blair to back a “humanitarian intervention” by NATO countries to protect Kosovar Albanian civilians and force Yugoslav forces to pull out.

Or conflicts where the U.S. and other outside powers did little or nothing to intervene, such as the genocide in Rwanda, just a few years before the Kosovo War.

Leaders will also doubtless recall U.S. and British decisions not to enforce President Barack Obama’s “red line” pledge to take military action if Syria’s dictator Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons.

Seeking – and failing to win – parliamentary approval for Britain to join this red line response in 2013, then-Prime Minister David Cameron was blunt in his assessment of the Iraq War’s impact. “One thing is indisputable,” he said in his speech. “The well of public opinion was well and truly poisoned by the Iraq episode and we need to understand the public skepticism."

In that light, it may well turn out that there is another lasting casualty of the Iraq War: future Western leaders’ readiness to mount a military response, even to such “values” challenges.

Difference-maker

Women of Winter brings inspiration, diversity to slopes

Catching air on the slopes is often a white male realm. But Women of Winter is training snow-sports instructors to help diversify the slopes.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Jodi Hausen

Raised in Hawaii by an Austrian father and Filipino mother, Chris Walch learned to ski in her 20s in Austria. With long black hair and brown skin, she stood out, and, as a new skier, it made her uncomfortable.

“I felt like I had a lot of eyes on me,” she says. “But I really wanted to ski, and if that’s the cost that came with it, that’s the cost that came with it. ... [It’s] not the cost that I want anyone else to have to pay.”

Ms. Walch went on to careers in law and high-tech but decided to help diversify ski slopes dominated by white men. Her nonprofit, Women of Winter (WoW), trains women of color to teach snow sports and be models for other women not often represented on the slopes.

In early March in Big Sky, Montana, she trained 32 women of color from around the country to be snow-sports instructors.

“Immediately I felt a sense of belonging, which is something I’ve never really experienced on the mountain before,” says Yolanda Carlton, a WoW graduate who instructs at Liberty Mountain in Pennsylvania. “[It] opened my mind to all the possibilities and opportunities. This, right here, is my retirement plan.”

Women of Winter brings inspiration, diversity to slopes

On a recent snowy weekday afternoon, Chris Walch shuffles her skis in a lift line at Big Sky Resort – she’s multitasking to the max. Founder of a high-tech business, she texts for work on her smartphone while, in her other role as the founder of Women of Winter (WoW), she’s guiding a group of women of color, like her, up to a black diamond bowl at 9,500 feet.

She’s one of several snow-sports instructors training women to pursue outdoor adventures and become models for other women not significantly represented on the slopes. Today, she’s on one of several runs with this group of Black, Hispanic, and Asian women who’ve come here from around the country to train for a Professional Ski Instructors Association (PSIA) exam.

The course is meant to produce women ski instructors of color who can take teaching skills back to their local ski hills. For many, the class provides a sense of inclusion on the slopes they’ve rarely felt.

WoW instills a sense of belonging in the snow-sports environment that has been “predominantly pale and male,” says Peggy Hiller, PSIA chief executive officer. “There’s a huge opportunity to grow our instructor base to represent our entire population, which includes women and people of color.”

Ms. Walch, who grew up in Hawaii, the child of an Austrian father and Filipino mother, learned to ski on the Austrian slopes in her 20s. She stayed in the Tyrol region to teach. With long, midnight black hair and brown skin, she stood out and was easily spotted on the mountain. And, as a new skier, this made her uncomfortable. She says she was considered “exotic,” with students often requesting “the Hawaiian instructor.”

“I felt like I had a lot of eyes on me no matter what I did,” she says. “But I really wanted to ski, and if that’s the cost that came with it, that’s the cost that came with it ... [it’s] not the cost that I want anyone else to have to pay.”

Ms. Walch went on to become an attorney for Fortune 500 companies. She decided to use Chris instead of her full given name, Christeen, because, she says, “You’d be surprised how many people take you more seriously when they think you’re a white man.” She still smiles recalling people’s surprise learning she was not only a woman, but a woman of color.

She founded WoW in 2018 while also establishing her own business, LifeScore, an award-winning artificial intelligence music-creation platform used for live-synchronized driving playlists in luxury vehicles and television soundtracks. WoW initially started as an inspirational storytelling event in Bozeman, Montana.

Two years in, Ms. Walch says, the organization pivoted “from inspiration to action,” providing opportunities for women to participate in winter adventures with funding from local businesses and nonprofits, as well as sports-equipment companies like Rossignol. Since 2020, WoW has awarded more than 100 scholarships to women of color to attend events including professional snow-sports instructor certification, avalanche safety, and

performance-enhancing mindfulness training. Women participating in snow-sports instructor certification also receive a comprehensive gear package and lift tickets, making an expensive sport more accessible.

The 32 women who participated in this month’s WoW trainings arrived from across the country, and their sense of joy was palpable.

Valentina Codrington, a business analyst from Baltimore, wore stylish flowered ski pants and was excitedly anticipating her instructor certification. She recalls once walking by a bus of children of color at a ski resort and intentionally removing her hat to expose her long, dark braids. When they saw someone who looked like them, she says, she witnessed their faces register confidence knowing they were welcome.

A sense of belonging

Former WoW scholarship recipient Yolanda Carlton, who works in IT security for the federal government, came from Washington, D.C., to ski with this year’s students. She teaches at Liberty Mountain Resort in Pennsylvania, an area attracting a diverse clientele. However, out of 200 instructors there, she says, only about five are people of color and only two of those are women.

“When I first came to be with the Women of Winter, immediately I felt a sense of belonging, which is something I’ve never really experienced on the mountain before,” Ms. Carlton says. Seeing women with so much experience in snow sports “opened my mind to all the possibilities and opportunities,” she adds. “This, right here, is my retirement plan.”

The National Brotherhood of Snowsports (formerly Skiers), founded as a nonprofit Black ski organization, recently welcomed more than 2,100 attendees to its 50th anniversary event for people of color at Vail Resorts in Colorado. Henri Rivers, its president, says people of color, who often live in urban areas, aren’t heavily exposed to nature. He explains that part of his organization’s mission to offer outdoor recreation experiences is to impart an understanding of climate change and to promote inclusivity.

“It’s not about breaking up the monopoly of white people having fun in the outdoors,” he says. “It’s for everyone.”

Ms. Hiller, at PSIA, agrees: “I think it’s really important to be welcoming and inclusive to all people who want to join our sport, and instructors are the gateway. [Snow-sports] teachers need to represent our student base.”

Shared experiences

It wasn’t difficult procuring industry support for the WoW mission. After all, the more people involved in snow sports, the better for the industry. The biggest challenge, Ms. Walch says, was proving that the boost for women of color is needed, because so many people don’t believe it’s necessary. It is not uncommon for people to post racist or antagonistic comments about the group online, she says.

“I can’t change the world,” she says, “but I think I can change the world I live in. So, I’m going to focus on that.”

That focus, she adds, is that “people want community. And one of the ways that we connect with people is our background, what we’ve gone through. So, creating spaces where there is community for people of color, specifically, we have a shared experience and we can show up and be vulnerable and be OK and say, ‘Oh yeah, we understand the things you’ve gone through.’”

On Broadway, saying goodbye to ‘Phantom’

The allure of “The Phantom of the Opera” is about more than catchy songs. Decades of theatergoers have found personal connections to the story.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Stephen Humphries Staff writer

When “The Phantom of the Opera” closes next month after more than three decades on Broadway, it will leave behind a formidable legacy.

For its many fans – or Phans – the production’s enduring popularity comes down to its memorable melodies and a universally relatable story about whether true love is skin deep.

“There’s just so many stories you hear at the stage door from people [about] the ways the show relates to them,” says Ben Crawford, who has played the titular character on Broadway since 2018, in a phone interview. “People who think they can resonate with the phantom if they feel different or they’re treated differently. There’s a connection there.”

The Majestic Theatre opted to shutter “Phantom” due to slow ticket sales after the pandemic. Ironically, the announcement of the musical’s closing created a surge in demand that, as of mid-March, has made “Phantom” the highest grossing musical on Broadway.

At a recent performance, theatergoers shared what the show has meant to them.

“For so many people, this got us into theater and wanting to come see more shows,” says New Yorker Christina Bacigalupo. “It was nice to come and see it one last time and give it the respect it deserves.”

On Broadway, saying goodbye to ‘Phantom’

On a midweek night, Noah Boice is one of the first people waiting in line outside the Majestic Theatre. He’s flown here from Detroit to see “The Phantom of the Opera.” After 35 years, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s epochal musical is about to end its historic run on Broadway.

“I’ve wanted to see it ever since I was a little kid,” says the chef. “In high school I wanted to audition for ‘Phantom.’ I didn’t get the role, unfortunately, because I don’t have the voice.”

Dressed for the occasion in a tartan suit that complements his red beard, he’s taking in the scene of his pilgrimage. Above the theater marquee, a digital billboard displays the most recognizable iconography on Broadway: a white mask next to a red rose. They symbolize the love story of a beautiful singer and a 19th-century musical genius who secludes himself because of his disfigured face.

“Basically, the main story of it is don’t judge a book by its cover,” says Mr. Boice.

“Phantom” will leave behind a formidable legacy. An early prototype of the megamusical, it helped transform Broadway into a magnet for overseas tourists. The Majestic opted to shutter “Phantom” due to slow ticket sales after the pandemic. Ironically, the announcement of the musical’s closing created a surge in demand that, as of mid-March, has made “Phantom” the highest grossing musical on Broadway. The original end date was pushed back from February to April 16. For its many fans – or Phans – the production’s enduring popularity comes down to its memorable melodies and a universally relatable story about whether true love is skin deep.

“There’s just so many stories you hear at the stage door from people [about] the ways the show relates to them,” says Ben Crawford, who has played the titular character on Broadway since 2018, in a phone interview. “People who think they can resonate with the phantom if they feel different or they’re treated differently. There’s a connection there. So there’s a lot of things that people can personalize in the show.”

Thirty-five years ago, Broadway audiences were predominantly locals from the New York area. As productions became more expensive to mount, the theater industry was eager to internationalize its audience. Cue the dramatic organ fanfare (DUHN dun dun dun DUHN) and enter “Phantom.”

Mr. Lloyd Webber had already established himself a household name with mass appeal hits such as “Jesus Christ Superstar,” “Evita,” “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat,” and “Cats.” “The Phantom of the Opera” eclipsed them all.

The love duet “All I Ask of You” and “The Phantom of the Opera” – both Top 10 hits on the U.K. singles chart – are firmly embedded in millions of mental jukeboxes. It also spawned a 2004 movie version, starring Emmy Rossum and Gerard Butler, as well as several cast recordings from various stage productions – including the very first one in London in 1986.

“It’s a show that doesn’t date itself,” says Jessica Sternfeld, author of “The Megamusical.” “There’s enough of a sense of classical music about it that it doesn’t quite holler, ‘I’m from the 1980s,’ the way other shows do.”

Long before “The Lion King” roared on stage, “Phantom” employed Disney-like branding with a worldwide reach, says Elizabeth Wollman, author of “The Theater Will Rock: A History of the Rock Musical, from Hair to Hedwig.” In New York, where tourists accounted for 65% of pre-pandemic Broadway audiences, the $1.3 billion grosses for “Phantom” overall have only been surpassed by “Wicked” and “The Lion King.”

To understand the longevity of “Phantom,” Dr. Wollman suggests putting yourself in the mind of a first-time visitor to Broadway: “I’m with my family. I don’t know New York very well. I want something that’s comfortable that I’ve heard of before, that I think we’re all going to understand. That’s not going to be too risqué for my children. That’s not going to bore me to tears.”

Standing outside the Majestic, Zack and Sarah Inman from Bowling Green, Kentucky, are quick to praise Emilie Kouatchou, the first Black woman to play the role of Christine.

“She was actually Christine when we saw it in 2021,” says Ms. Inman. The couple have lost count of how many times they’ve seen “Phantom” either on tour or here in New York. “Seven or eight,” says Ms. Inman.

Emily Pringle, of Long Island, can boast an even higher number. She’s seen it 12 times. The first time was when she was 10 years old. Most recently, she attended the 35th anniversary performance on Jan. 26.

“They had confetti at the end,” says the student, who is at the theater filming a documentary about the show closing on Broadway. “Ben [Crawford] gave a really good speech at the end. Andrew Lloyd Webber was there.”

Attendees milling in the lobby have flown in from places like Massachusetts, Texas, and Missouri. The excited voices include Russian and Chinese tourists. The merch stand is doing robust business. Its memorabilia include a teddy bear dressed in a tuxedo, cape, and a mask – probably not the kind of thing one gives a toddler at bedtime.

“There’s this intrigue to the character of the Phantom,” says Yacine Ndaw, a New Yorker who first saw the show when she was 13. She’s drawn to a story that’s as unpredictable as the moment when the Phantom suddenly appears on a gangway high above the audience. “You watch the whole show and you understand a little bit more who he is.”

The masked character is a musical composer who’s been ostracized because of his facial deformity. Hiding in the catacombs of a Paris opera house, he demands that its new owners stage his latest work, “Faust.” He also insists that they cast a young singer, Christine, in the lead role. He’s infatuated with her. And he’s also jealous of Christine’s childhood friend, Raoul, who is wooing her. When things don’t go the Phantom’s way, he kills people. To some, the character is a troubling figure whose possessive stalking of Christine is abusive. Not to put too fine a point on it, but he is also a serial killer.

“If you just play him as the bad guy and the murdering sociopath, then you really lose a lot of the layers involved in the character,” says Mr. Crawford.

“You have to make sure that they understand the humanity aspect of him,” he adds. “And I think if you can find a way to show that he’s lashing out because he’s been mistreated his whole life, you don’t condone his behavior, but you can at least understand it.”

At the climax of the show – spoiler alert – Christine tells the unmasked composer, “This haunted face holds no horror for me now. It’s in your soul that the true distortion lies.” In an act of kindness, she embraces him.

He has a sort of revelation in that moment, it’s not the way he looks, but how he is, that makes him “unfit to live among us,” says Dr. Sternfeld, who is an associate professor of music at Chapman University in Orange, California.

At a February performance, it’s not the famous scene of a crashing chandelier that threatens to bring the roof down. It’s the extended applause during the encores. Afterward, Tony Bacigalupo stands outside the theater chatting with his wife, Christina, about the performance.

“I remember I leaned over to you at some point early on in the show and said, ‘Look, we’ve seen a lot of shows together, but this one is different,’” says Mr. Bacigalupo, a New Yorker. “They clearly were going for it. With this one, there was no holding back.”

Ms. Bacigalupo marvels at how the Phantom made her root for him despite his crimes. She “happy cried” at the end.

“For so many people, this got us into theater and wanting to come see more shows,” says the one-time college theater major. “It was nice to come and see it one last time and give it the respect it deserves.”

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story included comments about how often “Phantom” tours. “Phantom” has had long stretches on tour, but the show is not yet available to community and regional theaters.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Breaking the fear of witchcraft in Africa

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Over many years, Africa has seen a growth in community initiatives to tackle one of the most widespread and least acknowledged causes of violence on the continent: fear of witchcraft. Often unseen, these projects have helped to diminish stigmas, restore social unity, and uphold individual dignity.

Last week this progress received an important boost. The African Union set out guidelines for how its member states should address the societal harms arising from popular beliefs about witchcraft. Though unenforceable, they are an acknowledgment that a problem long shrouded in silence is inconsistent with Africa’s shared principles of justice and equality.

“Although witchcraft accusations and witch-hunting are against the law in many African countries, these legal provisions are seldom enforced,” writes Leo Igwe, a Nigerian human rights advocate. The new guidelines, he states, mark an important step toward “weaken[ing] the grip of witch and ritual beliefs on the minds of Africans.”

With its new guidelines, the African Union has helped break the silence on a difficult subject. By doing so, it may reveal that the simple warmth of the human heart is the most profound remedy for hate and fear.

Breaking the fear of witchcraft in Africa

Over many years, Africa has seen a growth in community initiatives to tackle one of the most widespread and least acknowledged causes of violence on the continent: fear of witchcraft. Often unseen, these projects have helped to diminish stigmas, restore social unity, and uphold individual dignity.

Last week this progress received an important boost. The African Union set out guidelines for how its member states should address the societal harms arising from popular beliefs about witchcraft. Though unenforceable, they are an acknowledgment that a problem long shrouded in silence is inconsistent with Africa’s shared principles of justice and equality.

“Although witchcraft accusations and witch-hunting are against the law in many African countries, these legal provisions are seldom enforced,” writes Leo Igwe, a Nigerian human rights advocate. The new guidelines, he states, mark an important step toward “weaken[ing] the grip of witch and ritual beliefs on the minds of Africans.”

The United Nations has cataloged some 20,000 victims of violence tied to fears or practices of sorcery across 60 countries worldwide in the past decade. In Africa, that violence takes many forms, but is targeted at children, women, older adults, and people with albinism. Those suspected of witchcraft are subjected to ostracism, disinheritance, mutilation, rape, and ritual killings. Accusations often flourish during crises as an explanation for misfortune.

Suspicions are rife and as difficult to disprove as they are to prove. An American University study published last November found that “witchcraft beliefs are substantially more prevalent in countries with weak institutions and low quality of governance.” Suspicions proliferate where there are limited public health services or opportunities for education and employment.

The African Union guidelines combine a wide range of remedies meant to reinforce the protocols that African states have already adopted to promote gender equality, protection of children, and defense of human rights. Eight countries have laws making accusations of witchcraft against children or people with albinism a crime. Malawi, one of the world’s poorest countries, has achieved modest declines in violence by boosting civic awareness and more equitable access to higher education.

Community-led projects have shown that breaking the fear of witchcraft requires changing perspectives. In Ghana, where women accused of sorcery are held captive in remote, makeshift “witch camps,” a group of civil society organizations found that boosting ownership and entrepreneurship in local communities helped build local philanthropic support for the banished women. Grains of empathy turned into reservoirs of renewed trust.

Across Africa, people with albinism are often seen as ghosts and face severe violence from a belief that their body parts can heal. A project in Tanzania has seen those attitudes melt away through contact. As a study published last month in the journal Disability and Society found, the key to change was personal agency. When people with albinism were given opportunities to tell their stories and show their common humanity, attitudes toward them changed. Through reason and contact with people in his community in a controlled setting, one informant said, people discovered that “he is just normal, he will not disappear, he is a normal human being, he is intelligent, he is funny, he has a good heart.”

With its new guidelines, the African Union has helped break the silence on a difficult subject. By doing so, it may reveal that the simple warmth of the human heart is the most profound remedy for hate and fear.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Before they call, I will answer’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

When we learn to trust the intuitions that come from God, we find helpful guidance and protection.

‘Before they call, I will answer’

Intuition is one of the more elusive qualities to define, and yet we can all point to a time when we’ve felt it. Some may define it as an inner voice beyond logic.

In Scripture we read, “And it shall come to pass, that before they call, I will answer” (Isaiah 65:24). Doesn’t this sound like those gut feelings we get, and point to God as their source?

Indeed, Christian Science teaches that this capacity to know what we need to know when we need to know it is derived from our oneness with God as His children. The author of “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” Mary Baker Eddy, writes, “Spiritual sense, contradicting the material senses, involves intuition, hope, faith, understanding, fruition, reality” (p. 298). And she defines spiritual sense as “a conscious, constant capacity to understand God” (p. 209).

Spiritual sense comes from God, the one all-knowing divine Mind, which we each reflect. It reveals what is good and right, showing us the truth about God, Spirit, as good and about ourselves as God’s offspring – not mortal, but wholly spiritual, expressing the wisdom of divine Mind. And it cuts through the foggy views of existence given by the physical senses.

Even when we are feeling our way along the dark corridor of confusion or indecision, we can humbly yield to spiritual sense, which helps us become more acutely aware of God’s leading. God says to each of us in ways we understand, “This is the way, walk ye in it” (Isaiah 30:21). In truth, God, divine Love, is always directing us. This is the Christ, Truth, at work, helping us realize that we are always loved and cared for by God.

We can recognize when it’s God that is guiding by the quiet sense of peace that accompanies God’s messages. As we open our hearts to the spiritual reality of harmony for all of God’s children, the push and shove of anxious decision-making evaporates and a deep, settled calm prevails. We find we have the wisdom to discern the right steps to take and the right timing to take them. Divine Mind is more powerful than any roadblocks that would hamper progress, and is here to bless us each step of the way.

This has been proven true many times in my life. Once, my husband and I were notified that we needed to move out of our apartment very soon. I immediately began praying for guidance, and we found a well-located, bright, and affordable possibility for our new home.

Then, a few days later, we were offered another option that was larger and would have been even more affordable. To all appearances this was the better deal, but I had an uneasy feeling, an intuition not to take it, and we declined the offer.

It turned out this was the right decision, because we found out later that the second option wouldn’t have been available after all. Had we pursued that route instead of sticking with the other place we had found – which ended up meeting our needs beautifully – we would have been back at square one, with our move-out deadline looming.

We can learn to trust the divine intuitions coming from God. As we listen to God’s seamless guidance, we find answers that meet our needs, and we’re protected from making unwise decisions.

Intuition is not selectively bestowed on some and not on others. As God’s offspring, we all have it. Haven’t we all at one time or another felt a clear guiding hand directing us? Understanding what this is and where it comes from makes us more attuned to God’s messages of comfort and peace, which we can then act on. True intuition is the fulfillment of God’s promise, “Before they call, I will answer” – a promise that is reliable and always available.

Viewfinder

Sky blue

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when our Howard LaFranchi looks at how the United States is handling the situation in Israel. Benjamin Netanyahu’s controversial plans to recast the judiciary threaten the “shared democratic values” that politicians from both countries have traditionally extolled.