- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 11 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Tracking down Judy Blume’s coming-of-age book

Say the words “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” and many women may recall just where they were when they first heard about the coming-of-age book by Judy Blume, published in 1970.

Ms. Blume has been granted entry as a confidant into a place where few are admitted: the tween bedroom. Her character Margaret Simon explores questions all young girls wonder about but are too embarrassed to ask.

When I started reporting on Ms. Blume’s lasting appeal over the past 50 years, which you can read about in today’s Daily, I wanted to reread the book. I could visualize the purple paperback cover with Margaret’s flowing blond hair, and I dug through boxes in the attic looking for it. But my copy is long gone. I stopped by the local library. Both copies were checked out. Next, I searched eBay. Even though the book is still in print, it turns out nostalgia for certain covers comes at a cost. I spotted the familiar 1977 edition for $85, so I passed.

Finally, in a tiny bookshop on Beacon Hill in Boston, I found the title on a low shelf. Somehow seventh grader Margaret, after five decades, is still holding her own among today’s vampire trilogies, dystopian stories, and graphic novels. The cover of my new copy features Abby Ryder Fortson, the young actor who portrays Margaret in a new motion picture that opens April 28.

At the bookshop, I headed down to the cafe to meet a friend. The chef, dressed in a crisp white coat, led us to our table. I set down my newly purchased book and that’s when she paused. She placed one hand on the book, and the other on her heart, and turning to me she said, “I remember exactly where I was when I read this book and how it made me feel.”

And I knew just what she meant.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can Republicans avoid political cliff on abortion?

The Republican Party won a victory in overturning Roe v. Wade, but it may have put itself in a more precarious position politically. Candidates are navigating a new landscape – often silently or awkwardly.

-

Story Hinckley Staff writer

When Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis appeared last Friday at the Christian conservative Liberty University in Virginia, hours after quietly signing a ban on abortions beyond six weeks of gestation, he didn’t mention the topic.

Meanwhile fellow Republican Nikki Haley, on the presidential campaign trail in Iowa, doesn’t mention abortion until asked. “I am strongly pro-life,” she says, noting that her husband is adopted and that she had trouble conceiving both of her children. Still, she’s quick to add, “I don’t judge anyone that’s pro-choice any more than I want them to judge me being pro-life.”

The awkwardness and hesitancy on display among prominent Republicans when talking about abortion these days reflect a profound challenge facing their party heading into 2024: The overturning of Roe v. Wade set off a political backlash that has energized Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, as seen in votes in Wisconsin, Kansas, and other states since the ruling.

The few Republicans in Congress willing to carve out a middle ground on abortion suggest that their efforts are a work in progress. Rep. Nancy Mace of South Carolina has been a lonely voice on the matter, calling herself “pro-life” but also saying that she’d lean toward banning the procedure after “15 to 20 weeks” of gestation.

Can Republicans avoid political cliff on abortion?

Nikki Haley moves briskly through her talking points – on the federal budget, education, transgender matters, immigration.

But at her “Women for Nikki” launch event last week in Des Moines, Iowa, the Republican candidate for president doesn’t voluntarily touch upon what may be the hottest topic in politics today: abortion.

Only when an audience member brings it up does Ms. Haley – former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and former governor of South Carolina – address the subject.

“I am strongly pro-life,” she says to applause, noting that her husband is adopted and that she had trouble conceiving both of her children. Still, she’s quick to add, “I don’t judge anyone that’s pro-choice any more than I want them to judge me being pro-life.”

Ms. Haley then says she doesn’t want “unelected justices deciding something this personal. I want to make sure that it’s decided where the people’s voices are heard.”

Her answer suggests a small-d democratic approach to a deeply divisive topic. But the issue has become exponentially more complicated since last June, when the Supreme Court overturned the nationwide right to abortion. The South Carolinian plans to deliver a major policy speech on abortion next Tuesday.

Other high-profile Republicans running, or likely to run, for president in 2024 are also treading carefully on the issue – if they mention it at all. Thus far, former President Donald Trump has said nothing about the new law in his home state of Florida banning abortion after six weeks’ gestation, one of the strictest laws in the nation.

And when Ron DeSantis – Florida’s Republican governor and a likely ’24 entrant – appeared last Friday at the Christian conservative Liberty University in Virginia, hours after quietly signing the abortion bill late at night, he didn’t mention the topic.

Then there’s GOP Sen. Tim Scott of South Carolina: On the day he announced an exploratory bid for president last week, he declared himself “100% pro-life,” and then offered an incoherent response that quickly went viral when asked if he’d support a federal abortion ban.

The awkwardness and hesitancy on display among prominent Republicans when talking about abortion these days reflect a profound challenge facing their party heading into 2024: The overturning of Roe v. Wade caught Republicans flat-footed and set off a political backlash that has energized Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, as seen in votes in Wisconsin, Kansas, and other states since the ruling.

Abortion was one of the top three issues for Democrats heading into the 2022 midterms, according to Pew Research Center. Furthermore, it could hinder the GOP’s ability to retake the presidency, political analysts say.

The price of a legal victory

In some ways, it’s ironic: By actually achieving a decadeslong goal for its base, the Republican Party may have put itself in a more precarious position politically. With Roe gone, many of its conservative foot soldiers now lack a unifying policy objective on abortion – and any new federal restrictions risk further alienating moderates and independents.

“The five-to-four majority in Dobbs thought they were doing anti-abortion people a favor,” says David Garrow, a legal historian on reproductive rights, referring to the Supreme Court ruling that overturned Roe. Indeed, the number of legal abortions in the United States declined by 6% in the first months after Dobbs. But in political terms, Mr. Garrow adds, “to some extent, they’ve done the Democratic Party a favor.”

Even as a talking point, the issue has become a minefield for Republicans. While most GOP politicians still call themselves “pro-life,” many are reluctant to be more specific about what that means, knowing that it could put them out of step with voters.

Major opinion polls have consistently shown that a majority of Americans say abortion should be legal in most cases – currently 93% of abortions occur within the first trimester of pregnancy – and that the decision should be up to the woman and her doctor.

The issue has been further inflamed by the recent drama over so-called medication abortion, in which a federal judge in Texas ruled early this month that the drug mifepristone was improperly approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2000. The drug is one of two medications used in nonsurgical abortions, which account for about half of all pregnancy terminations.

On Wednesday, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito extended until Friday a stay on a lower-court ruling out of Texas blocking the use of mifepristone, allowing the justices more time to consider the case.

The Texas case has only raised the stakes in the modern-day practice of reproductive health. When Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization was handed down last June, some abortion-rights advocates found solace in the fact that a woman living in a state with strict limits could still acquire medication to end a pregnancy, and therefore would not have to travel to a more permissive state for a surgical abortion.

Now, supporters of abortion rights say, the medication option also hangs in the balance – even for states where abortion is legal. And the impact of legally limiting or banning mifepristone goes beyond abortion: The drug is also widely used to treat women who are miscarrying, and limits on its use could harm women experiencing the loss of a wanted pregnancy, physicians say.

A victory for anti-abortion forces in the Supreme Court on mifepristone would likely make the backlash against Republicans over abortion even worse.

Warning signs for Republicans

In navigating the post-Roe political landscape, social-conservative activists know they have a challenge on their hands.

Since Dobbs, statewide votes in which abortion rights have been at stake have shown that a sleeping giant – college students – can be activated. And the suburbs, once a Republican stronghold in many red and battleground states, edge toward the center.

Those trends proved critical last August in solid Republican Kansas, where the abortion-rights side won handily in a statewide referendum to amend the state constitution. Earlier this month, in battleground Wisconsin, the liberal candidate in a vote for state Supreme Court justice also won easily, with abortion rights on the line.

In Michigan, too – another battleground state – a referendum last November to put abortion rights into the state constitution won decisively. By driving turnout, the measure also helped Democrats win the governorship and both legislative houses for the first time since 1984.

These are just three states, but the results delivered a message to both camps on the politics of abortion. When Roe was still in place, it acted as a limiting force around any proposed restrictions on the procedure. Now, the only limiting force is the voters.

“States now have the freedom, with the Dobbs decision, to implement restrictions that, before then, have just been hypothetical,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia.

Ralph Reed, founder and chair of the Faith and Freedom Coalition, acknowledged that his side is “on our back heels” post-Dobbs. Needless to say, he and others don’t see congressional action to restrict abortion happening anytime soon, since the GOP would need a 60-vote veto-proof majority in the Senate. They also would need to do some serious work to bring the country along.

“We’ll get there eventually, but it’s just going to take a while,” says Mr. Reed.

A middle ground?

The few Republicans in Congress willing to carve out a middle ground on abortion suggest that their efforts are a work in progress. Rep. Nancy Mace of South Carolina has been a lonely voice on the matter, calling herself “pro-life” but also saying that she’d lean toward banning the procedure after “15 to 20 weeks” of gestation.

“With the vast majority of Americans, there’s common ground,” Representative Mace said on Fox News last Sunday.

South Carolina GOP Sen. Lindsey Graham is also aiming for what he sees as a compromise on abortion, introducing legislation with a 15-week gestational limit, and exceptions for rape, incest, and endangered maternal health. He would also leave in place more restrictive bans approved at the state level.

But in unveiling his bill just weeks before last November’s midterm elections, when members are especially risk-averse, Senator Graham didn’t win many co-sponsors. The effort is currently on hold. A divided Congress, and close margins of control in each chamber, means any nationwide effort to set abortion policy is most likely a nonstarter. Efforts to “codify Roe” legislatively – led by GOP Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska – have run aground.

And so for now, both sides of the divide are eager to show their popular strength in Washington and around the country. In January, on the 50th anniversary of Roe – months after its demise – thousands of people gathered on the National Mall for the annual March for Life.

But the energy is clearly more intense on the other side. Supporters of abortion rights have staged numerous demonstrations in the past year, starting when the Dobbs ruling leaked last May. Last Saturday, outside the Supreme Court, some 500 protesters turned out against the federal judge’s ruling on mifepristone. Similar protests played out across the country.

It’s an issue that speaks to people of all ages and circumstances – people of child-bearing age, older people with memories of life before Roe and who are concerned for their children and grandchildren, women hoping to get pregnant but fearful that limits on medical care could lead to bad outcomes. And not all are Democrats.

Nicole Altomare, a political independent in her late 30s from Arlington, Virginia, came to the Supreme Court on Saturday because she’s trying to have a family and is worried that doctors might face limits in what they can do to help her – including prescribe mifepristone in the event of a miscarriage.

“I’m from Indiana originally, and every time I think about going home, I’m like, well, if I were pregnant, I’d have to stay near the Illinois border in case I needed help,” Ms. Altomare says, referring to Illinois’s more permissive health care laws.

Peggy Donakowski from Sterling, Virginia, who is in her 60s and has an adult daughter, describes herself as a “former Republican” who came out to protest because “every person who shows up makes a difference.”

Abortion matters, she says, because “everyone should have choice in a full-functioning democracy, including women – especially women, in that we have fought so hard to be where we are. Chipping away at this right is a slippery slope for all of democracy.”

Trump’s advantage

For the 2024 Republican nomination, former President Trump sits comfortably atop the polls – and ironically, may be the candidate most able to weather the anti-GOP backlash over abortion rights.

“The person who’s done the most without saying it is Donald Trump,” says Republican strategist Doug Heye.

Mr. Trump nominated three of the Supreme Court justices who voted to overturn Roe, as well as lower court judges who oppose abortion rights, and also campaigned for anti-abortion legislators, senators, and governors who are now shaping statewide legislation.

“On this issue, he doesn’t have to say the word ‘abortion,’” Mr. Heye says. “You can hear him in the debate: ‘Do you like the judges? Next question.’”

At the same time, because Mr. Trump doesn’t have to reassure his base on the issue, he might actually have more room to appeal to the other side. Indeed, it’s not hard to envision the former Democrat who previously favored abortion rights now advocating for some kind of middle ground.

Meanwhile, Mr. Trump’s announced and likely primary opponents are struggling to address the abortion issue effectively, as they seek to win over both anti-abortion Evangelical voters and pro-abortion-rights moderates.

It’s a straddle that could undo even the most skilled of GOP presidential candidates not named Trump.

Some Republicans argue that opposing abortion rights was not the political liability last November that liberals make it out to be. Governor DeSantis won reelection in Florida – until recently a battleground state – by almost 20 percentage points. And GOP Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia won reelection easily in a presidential battleground state even though he had signed a strict anti-abortion “trigger” law in 2019, in anticipation of Roe’s demise.

“We know what the winning strategy is – and we know that pro-life candidates have to be clear about their position on protections for the unborn, and contrast that with the extremism of the other side,” says Kelsey Pritchard, director of state public affairs at Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America. “That’s what we saw in the midterms.”

She refers to Mr. DeSantis’ landslide victory in Florida as a prime example.

For President Joe Biden, who is expected to run for a second term, abortion could be the issue that paves the path to reelection, political analysts say. Just as Republicans have for years run for president based on their ability to nominate judges, now it’s an energizing argument for Democrats.

It’s also perhaps ironic for President Biden, as he is a devoted Catholic and used to identify as “pro-life.” Today, he says he’s personally opposed to abortion but believes women should have the right to make their own choices about their bodies.

Activists who identify as “pro-life” on policy, like Mr. Reed, say there are plenty of ways like-minded politicians can move the needle on this issue.

“If we’re going to say, ‘We want to make this choice of ending a life harder,’ we ought to make it easier for [pregnant women] to do the right thing,” Mr. Reed says. He supports “very robust increases in funding for adoption, and prenatal and postnatal care, maybe even government subsidies for the cost of delivery. It could end up being quite expensive, but it would be a very smart thing to do.”

Still, after Dobbs, the abortion debate is all about who can grab the “middle” – and right now, that seems to be Democrats. To be sure, the abortion-rights side has its absolutists – those who want no limits on the procedure at any time. But as with those holding the most conservative views on abortion, there’s not much purchase in public opinion.

“Republicans have pushed so far to the right, and are so far out of sync with public opinion,” says the University of Virginia’s Professor Lawless, “that it’s hard to see how they get back in.”

Patterns

Syrian dictator reenters Arab fold, reviving dilemma for US

The Arab Spring has turned into more of an Arab ice age, as autocrats throughout the region solidify their power. Washington faces a difficult but familiar choice – to back democracy or stability.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Twelve years ago this week, 100,000 Syrians packed into the main square of Homs to demand that President Bashar al-Assad resign. Today, after a brutal civil war that has killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians and seen government forces use tanks, indiscriminate air strikes, poison gas, and Russian military assistance to help to preserve his power, Mr. Assad is taking a diplomatic victory lap.

Last week his foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad, was discussing with neighboring states whether the Arab League might lift its 12-year suspension of Syrian participation in the group. This week, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister traveled to Damascus, while Mr. Mekdad flew to Tunisia to restore bilateral relations.

The Arab Spring is looking more like an Arab ice age, with autocrats back in charge in Tunisia and Egypt, and still in charge throughout the Gulf.

Syria’s rapprochement with its dictatorial neighbors raises thorny questions for U.S. policy in a region where Russia and China are wielding ever greater influence. It also highlights a core tension that has long vexed Washington’s Mideast policy – between a commitment to human rights and reliance on alliances with Arab states that routinely violate those rights.

That is no easier to resolve today than it has ever been.

Syrian dictator reenters Arab fold, reviving dilemma for US

The murderous regime of Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad is taking a diplomatic victory lap.

For millions in the Arab world who had yearned to cast off government by coercion, corruption, force, and fear, the moves now afoot to bring Syria back into the Arab League will feel especially disheartening.

They seem to represent a final step on the road from an Arab Spring to what is looking more like a new Arab ice age.

And the rapprochement raises thorny questions for the United States – about past, present, and future policy in a region where Russia and China are wielding ever greater influence.

It also highlights a core tension that has long vexed Washington’s Middle East policy – between America’s public commitment to basic human rights and reliance on security alliances with Arab states that routinely violate those rights.

These allies, chiefly Saudi Arabia, have shrugged off U.S. objections to normalizing ties with Mr. Assad – a leader who has used tanks, indiscriminate air strikes, poison gas, and Russian military assistance to help to gain control over most of his country after a dozen years of civil war.

In recent days, the signs of regional entente have been getting clearer.

Last week, Mr. Assad’s foreign minister, Faisal Mekdad, joined regional leaders in Saudi Arabia for talks on whether the Arab League might lift its 12-year suspension of Syrian participation in the group. This week, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister traveled to Damascus, while Mr. Mekdad flew to Tunisia to seal an agreement to restore bilateral relations.

The diplomatic shuttling is a dramatic sign of how starkly the region has changed since the outpouring of popular protest that became known as the Arab Spring. It also presents a complex policy challenge for the U.S. as it decides how far it’s willing – or able – to deploy its influence to shape what comes next.

It was 12 years ago this week that 100,000 Syrians packed the main square in Homs, north of Damascus, and called for President Assad to resign.

The Arab Spring, sparked by the self-immolation of a lone protestor in Tunisia, seemed to be gaining force. Tunisia’s president, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, had been forced to step down after 21 years in power. A tide of popular anger in Cairo had toppled an even more deeply embedded autocrat, Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak.

But the autocrats fought back. U.S.-allied governments in the oil-rich Gulf used carrots and sticks – handouts and handcuffs – to reinforce their position. In Egypt, the first free elections brought the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood to power, but army Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Sisi led a coup to overthrow their government. He is still in charge, overseeing a crackdown on dissent more brutal and widespread than Mr. Mubarak’s.

Syria’s political spring soon ended, too, when Mr. Assad decided to crush dissent and send his tanks to storm a number of cities; full-scale civil war, which has killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians and displaced 13 million, ensued.

What of Tunisia, where Syria’s foreign minister was welcomed this week?

It was the last surviving democracy born of the Arab Spring. But since 2019, when Kais Saied won the presidency on an anti-corruption platform, he has disbanded parliament, adopted a constitution placing unfettered power in his own hands, and arrested his critics.

The latest arrest, coinciding with Mr. Mekdad’s visit, targeted opposition party leader Rached Ghannouchi, speaker of the shuttered legislature.

American policymakers are now left to ponder what they can or should do in response to the autocrats’ return.

That’s partly a puzzle of their own making. Amid the political trauma stemming from the Iraq War, successive presidents have moved to scale back U.S. diplomatic engagement in the region, redirecting their focus toward China and, more recently, Ukraine.

As both China and Russia move to expand their own Middle East influence, Washington is pondering how, or whether, to use its still-considerable sway to resume a more active role.

That would mean again confronting the familiar tension in America’s Mideast calculations, between ambitions to promote human rights and decades-old alliances with regimes that flout them.

Even in the early days of the Arab Spring that tension sparked intense debates over how far Washington should go to encourage the pro-democracy protests. And when Islamist political parties expanded as the grip of autocracies loosened, the U.S. seemed increasingly to opt for the stability of its old-style alliances.

For both America and the demonstrators so hopeful of fundamental change during the Arab Spring, there remains an imponderable: Could another similar wave of popular unrest surge again?

Though the protests that erupted in 2011 demanded an end to autocracy, the main catalysts were economic and social – a thirst for jobs, affordable food, and a decent living, especially among young people in a region where youth unemployment remains the world’s highest.

And the 2011 Arab Spring taught the world one clear lesson, embodied in the dramatic demise of Egypt’s Mr. Mubarak.

It is that autocracies look unbreakable.

Until they are not.

Is this the end of affirmative action? If so, what comes next?

What would the end of affirmative action mean for students and their families? And how will colleges and universities pivot from what has been an entrenched status quo?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Ira Porter Staff writer

High school seniors all over the United States this month are getting their college acceptance letters. And it may be the last time that those letters go out under the system of affirmative action that has been in place in the U.S. for more than 50 years.

By the end of June, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on a case that may well end the practice of considering race as one facet of admissions in all U.S.-based institutions of higher learning.

On three different occasions, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld, on narrow grounds, the constitutionality of race-based affirmative action in university admissions. But as it prepares to rule in two cases involving admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina, the court appears poised to overturn that precedent.

Today’s Supreme Court appears likely to rule against Harvard and UNC. The next, and harder to predict, question: How broad will the ruling be?

Is this the end of affirmative action? If so, what comes next?

High school seniors all over the United States this month are getting their college acceptance letters. And it may be the last time that those letters go out under the system of affirmative action that has been in place in the U.S. for more than 50 years.

By the end of June, the Supreme Court is expected to rule on a case that may well end the practice of considering race as one facet of admissions in all U.S.-based institutions of higher learning.

What would the end of affirmative action mean for students and their families, particularly first-generation and low-income students? And how will colleges and universities pivot from what has been an entrenched status quo?

What is the Supreme Court case? Why is it happening?

On three different occasions, the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld, on narrow grounds, the constitutionality of race-based affirmative action in university admissions. But as it prepares to rule in two cases involving admissions policies at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina (UNC), the court appears poised to overturn that precedent.

Conversations around race-based affirmative action began in the 1960s, with Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson arguing that the policies were needed to help historically disadvantaged racial groups, particularly African Americans, achieve full equality.

When the Supreme Court first heard a constitutional challenge to affirmative action in college admissions, in 1978, it upheld the system – but not in the way Presidents Kennedy and Johnson articulated. In his controlling opinion, Justice Lewis Powell wrote that affirmative action is lawful because it furthers a state’s “compelling interest” of attaining a diverse student body.

“Anyone who has been involved in higher education understands diversity is a good thing,” says Geoffrey Stone, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, “but that’s not what [affirmative action] is really about.”

Since that 1978 case, he adds, diversity, not social justice, “has become the center point in how the court talks about affirmative action.”

While it has narrowed at the margins the lawfulness of affirmative action policies in college admissions – racial quotas are not allowed, for example – the high court has repeatedly ruled that the Constitution protects such policies because of those diversity interests. In a 2002 decision about a University of Michigan policy, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor wrote that “25 years from now, the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.”

Two decades later, the Harvard and UNC cases – both brought by the group Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) – are testing that aspiration. One case argues that Harvard’s policy unlawfully discriminates against Asian American applicants, and the UNC case makes similar arguments regarding white and Asian American applicants. Both universities won in the lower courts.

But at a five-hour oral argument last October, the court’s six conservative justices voiced deep skepticism about the universities’ policies and the court’s precedents.

“I don’t have a clue what [‘diversity’] means,” said Justice Clarence Thomas. “I didn’t go to racially diverse schools, but there were educational benefits.”

“When does it end?” asked Justice Amy Coney Barrett. “What if it continues to be difficult in another 25 years?”

How is it likely to turn out? What is at stake?

The Supreme Court appears likely to rule against Harvard and UNC. The next, and harder to predict, question: How broad will the court’s ruling be?

The answer to that question may tie back to the court’s blockbuster ruling last term: the decision to overturn the constitutional right to abortion in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health.

“They might do what they did in Dobbs and overrule all the precedents that have dealt with affirmative action,” says Professor Stone, co-author of a recent book arguing that race-based affirmative action is constitutional on social justice grounds. “But after Dobbs they may be a little more cautious, they may want to not look as partisan.”

Either way, universities should be preparing for life after race-based affirmative action, experts say. Exactly what they’ll be permitted to do won’t be clear until the Supreme Court’s decision is released (expected in June), however. And whatever the court does say, there is likely to be confusion.

“It will be interesting to see what institutions will do in that world,” says Professor Stone. “I don’t have a simple solution.”

But banning affirmative action, he adds, “isn’t going to make the issue go away.”

Giving extra weight to socioeconomic status is one possible solution, experts say.

Richard Kahlenberg, a nonresident scholar at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy, testified on this point as an expert witness at the district court level in the Harvard and UNC cases. He believes that universities focusing on socioeconomic diversity could even improve on the affirmative action policies of the past half-century by better addressing their social justice roots.

“Looking at economic disadvantages means we’re not ignorant of our history,” he says. “It’s precisely because of our history of discrimination that Black and Hispanic students are disproportionately poor.”

Conservative jurists like Justice Thomas and Justice Samuel Alito have both spoken favorably of admissions policies that favor lower-income students. An oft-cited model is Texas’s “Top 10 Percent” law, which since 1998 guarantees all students in the top 10% of their high school graduating class admission to all state-funded universities.

“Right now racial preferences create racial diversity but very little socioeconomic diversity,” he adds. “So long as selective colleges are seen as a bastion for the wealthy, that’s bad for the country.”

What effect would banning affirmative action have?

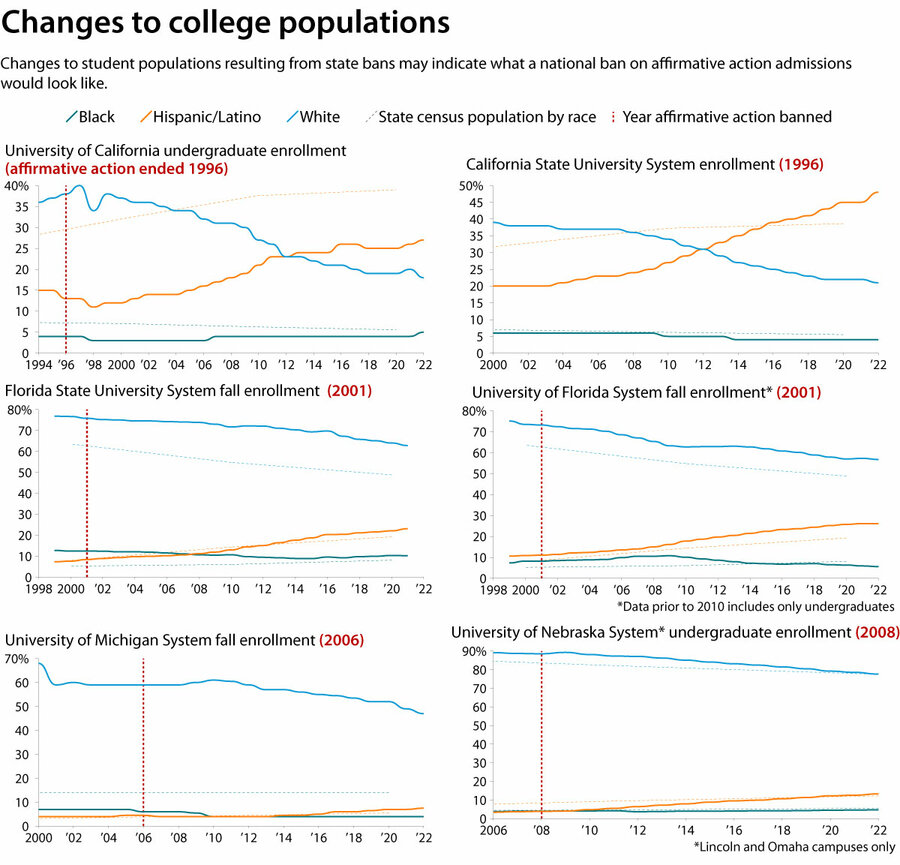

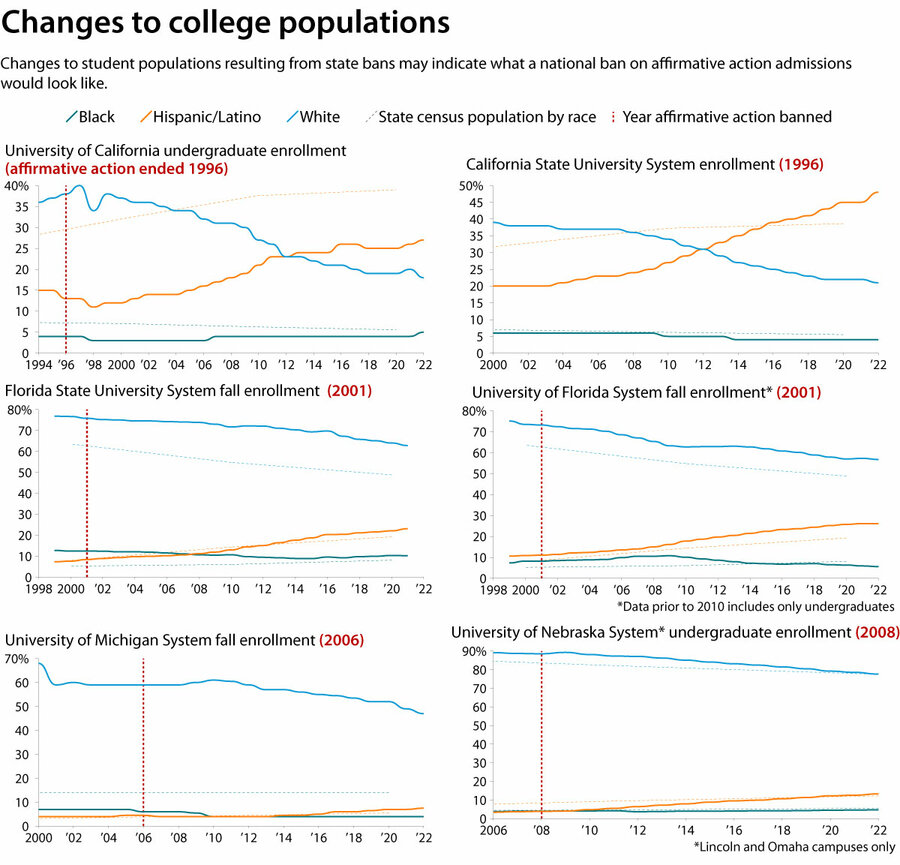

Affirmative action has been banned in nine states thus far. California moved first, when voters set Proposition 209 in action in 1996. It officially went into effect for public universities in 1998. Some of the most selective schools in the state system, such as the University of California, Los Angeles and the University of California, Berkeley, suffered steep declines in enrollment of underserved minority groups, who are economically or educationally disadvantaged as opposed to minority groups that may not face those issues. Underserved minority groups in California generally had a more difficult time getting into more selective schools.

Soon after the country’s largest state approved the measure, others followed. They included Florida (2001), Michigan (2006), Nebraska (2008), Arizona (2010), New Hampshire and Oklahoma (both in 2012), Washington (2019), and Idaho (2020).

Michigan public universities suffered enrollment declines, particularly among Black students. Representatives from schools in Michigan and California filed briefs to the Supreme Court arguing that racial diversity is impossible without affirmative action. The 10 schools in the University of California system educate more than 294,000 students and suffered precipitous drops in enrollment of underserved students after Prop 209. The most selective schools had a more than 50% drop in enrollment from those groups.

The California brief went further: “UC’s decades-long experience with race-neutral approaches demonstrates that highly competitive universities may not be able to achieve the benefits of student body diversity through race-neutral measures alone. To fulfill their role of preparing successive generations of citizens to succeed in an increasingly diverse Nation, universities must retain the ability to engage in the limited consideration of race contemplated by this Court’s precedents.”

University of California, California State University, Florida State University, University of Florida, University of Michigan, University of Nebraska

The University of Michigan said it was convinced of the broad educational benefits of a diverse student body. After the state banned affirmative action there in 2006 its Black population fell almost by half and it suffered losses to its Native American population. Michigan called its cooperation involuntary and said that it had been an unsuccessful experiment.

“The universities’ 15-year long experiment in race-neutral admissions thus is a cautionary tale that underscores the compelling need for selective universities to be able to consider race as one of many background factors about applicants,” the Michigan brief stated.

For its part, Florida argued that diversity could be achieved without special admissions and supported this with the percentage of Hispanic students enrolled in public schools before and after the state banned affirmative action.

How should colleges and universities prepare?

While the court’s decision is still unknown, many believe that it will abolish affirmative action in admissions, based on oral arguments. That could come in many forms, such as preventing applicants from being able to check a box for their race or ethnicity on college applications.

“But they might say you can’t take anything into consideration that has any sort of reference to race, and then that would include an essay, for example, or scholarship programs and things like that,” says Angel Pérez, chief executive officer of the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

Dr. Pérez says one of the biggest questions that high school guidance counselors ask is if students will be able to talk about their stories in an essay, which is particularly important for low-income or first-generation students of color, to present obstacles and struggles that they overcame. Many counselors encourage students to talk about lived experiences in their essays as a way to fully present themselves to universities. Essay questions are staple features on individual school applications and the common application, which many colleges and universities use.

Counselors sometimes specifically encourage students of color to talk about lived experiences and to apply for race-based scholarships, but that could be in jeopardy, Dr. Pérez says.

“Here’s where it gets more complicated. What happens to those scholarship programs?” he asks. “We don’t know.”

The issue is complex because it also informs the way development offices at colleges fundraise and engage alumni and donors for scholarship money based on particular communities. Some of those initiatives include drives to increase Black and Latino enrollment, says Dr. Pérez, who worked both as a high school counselor and in college admissions.

“College advising is going to change as a result, and high school counselors will need to relearn how institutions are going to function. That’s going to have a trickle-down effect on the entire sector,” he says.

Something else that is unknown but was discussed in oral arguments that might come from this case is the exclusion of legacy consideration, which currently gives potential students who are children of prominent alumni an admittance advantage. Some schools are taking steps to pivot before a decision is reached. Ivy League school Columbia University recently eliminated test scores for admissions consideration. Standardized tests have shown historically to favor mostly white students who can afford to spend money on test prep classes, as opposed to the underrepresented groups. Also, schools currently buy lists of names of students based on test scores, geography, and racial identity.

“So a school would say, ‘I want to buy the names of every Latinx student in Washington, D.C., who has above a 500 on the English essay,’” explains Dr. Pérez. “If that tool is taken away there goes another kind of marketing pipeline that used to be very traditional in the college admissions pipeline.”

University of California, California State University, Florida State University, University of Florida, University of Michigan, University of Nebraska

Books

Are you there, book lovers? It’s me, Margaret.

What makes a young adult novel that deals honestly with puberty endure across generations of women?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Judy Blume has been giving tween girls something to talk about ever since “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” was published in 1970.

Her iconic novel has been celebrated as a relatable guide for adolescent girls as much as it has been banned for its matter-of-fact discussions of menstruation. A new generation will get its chance to meet Margaret this month, when a big-screen version arrives April 28.

“She wrote a story that feels universal and relatable to anybody, any decade,” says director and screenwriter Kelly Fremon Craig in a Zoom interview. “When something is written with real honesty, that’s the effect it has.”

The story centers on Margaret Simon, who is navigating a new school and friends right at a time when she is feeling particularly self-conscious. Not sure what to do with her big feelings and questions, she shares her confusion directly with God.

After a recent screening in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one college student says she connected with the story, even though she never read the book.

“It was so realistic,” enthuses Sophia Perez, who says she used to pray to God to help her grow taller. “It really appealed to the kid in you and brought back all of those awkward feelings.”

Are you there, book lovers? It’s me, Margaret.

The one place where Angela Nguyen could spend unlimited time as a child growing up in Seattle was the library. She devoured books, especially coming-of-age stories. It was there, in the young adult section, where she encountered a book her middle school friends had been telling her about: “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret,” by Judy Blume.

“I didn’t know what it was before I read it. I thought it was going to be a religious book, to be honest. ... But I had friends who read it and said, ‘Oh, you should read this,’” says Dr. Nguyen, recalling schoolyard chatter from two decades ago. “‘It’s got girl stuff.’”

Judy Blume has been giving tween girls something to talk about ever since “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” was published in 1970. Her iconic novel has been celebrated as a relatable guide for adolescent girls as much as it has been banned for its matter-of-fact discussions of menstruation. A new generation will get its chance to meet Margaret this month, when a big-screen version (rated PG-13) arrives April 28.

The cinematic debut is a win for screenwriter and director Kelly Fremon Craig, a fan of the book who was the first – after others had tried for decades – to secure Ms. Blume’s blessing.

“She wrote a story that feels universal and relatable to anybody, any decade,” Ms. Fremon Craig says in a Zoom interview. “When something is written with real honesty, that’s the effect it has.”

Fans also have a documentary about the author to look forward to: “Judy Blume Forever,” aimed at viewers age 16 and over, is available on Amazon Prime Video starting April 21.

A lot has changed since Margaret’s debut five decades ago. Nearly half of U.S. states have passed laws or set aside funding that supports access to free period products in school bathrooms. Reusable sanitary products have wider acceptance and availability in the marketplace. Female athletes debunk cultural myths about the menstrual cycle and performance. But turmoil still swirls around when children should be taught about their changing bodies. A recent Florida bill would prevent teaching about menstruation in elementary school, even though some girls can get their first period as young as 8.

Ms. Blume’s book, written from the perspective of Margaret Simon, who is turning 12, has helped to fill the gap over the years on topics that adults can feel reluctant to address. The author has shifted the conversation around menstruation, say women’s public health experts, from something to hide or be ashamed of to something normal.

“In theory, everybody thinks parents are talking about [puberty] with their kids, but they’re really not,” says Marni Sommer, an adolescent health expert at Columbia University who has conducted research on three continents and co-authored “A Girl’s Guide to Puberty & Periods.” Ms. Blume’s writing talks about a sensitive topic “in a way that is confidence-building, and makes a young person feel normal,” Dr. Sommer adds.

“Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” is just one of Ms. Blume’s 29 books that combined have sold more than 90 million copies and been translated into about three dozen languages. The story centers on Margaret navigating a new school and new friends right at a time when she is feeling particularly self-conscious. Not sure what to do with her big feelings and questions, she shares her confusion directly with God. (She doesn’t identify with any particular religion, but has a Christian-raised mother and a father who is Jewish.)

For Dr. Nguyen, the only daughter of Vietnamese parents, Ms. Blume’s books were a lifeline in the midst of middle school.

“I grew up in a really strict household,” she says. “My mom never made me feel shame about getting my period, but it was not something we really talked about.”

Today she’s a postdoctoral researcher in menstrual health and education at Columbia.

Em Craig was only 9 years old when she sneaked “Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret” out of her older sister’s room. Ms. Craig reveled in the story, taking in Margaret’s first forays with sanitary pads and a trip to the department store to buy her first bra.

“It’s like getting gossip that’s just too good to share. You don’t even know how to share it,” says Ms. Craig, a graduate student at UMass Boston. She was reluctant to talk about the book with her sister, Victoria – or mother, even though she had read and loved the book herself. “It was too embarrassing to go to my mom, and it was embarrassing to talk to my friends, so it was like the book was the only resource.”

That feeling is a fairly universal experience, explains clinical psychologist Lisa Damour, author of the recently released book “The Emotional Lives of Teenagers.” She says early adolescents often exhibit two key features: “One is the drive towards autonomy – kids want to be independent; they want to be separate. The other is the drive for privacy.”

While Margaret may have turned to God for answers, scores of young readers turned to Ms. Blume, filling her mailbox with thousands of letters. In the 1980s those letters climbed to nearly 2,000 each month. Ms. Blume kept boxes of the missives, sometimes penning replies. She recently turned over the collection to Yale University to be housed in its archives.

Ms. Fremon Craig was an adult when she wrote her first letter to Ms. Blume. She had recently finished directing the 2016 comedy-drama “The Edge of Seventeen,” for which she also wrote the screenplay. She wanted to adapt the Blume book she had loved as a child since first learning about it while splashing around in a friend’s pool.

Ms. Blume agreed, and the director says working with the author was everything she hoped it would be. She is also quick to emphasize the importance of not only Margaret’s wondering if she’d ever fill out or kiss a boy, but also her spiritual journey. “I remember at that age, asking if there was something greater than us, if anyone was in charge,” she says. “You just want to know it’s going to be OK.”

During an interview on the “Today” show in January, Ms. Blume, who is a producer on the film, said she loved it. “How many authors of the book can say, I think that movie is better than the book?” she added.

After a recent screening in Cambridge, Massachusetts, one young woman in the audience says she connected with “Are you there God?” immediately, even though she never read the book.

“It was so realistic,” enthuses Sophia Perez, a songwriting major at Berklee College of Music in Boston, her ponytail of tight dark curls bobbing. She says she used to pray to God to help her grow taller. “It really appealed to the kid in you and brought back all of those awkward feelings.”

Em Craig’s mom, Lena, says she is looking forward to seeing the film with her two daughters.

“Everyone has those questions as kids. Everyone has family problems, or has to do something uncomfortable like moving,” she says. “It’s all timeless. It’s all relevant.”

In Pictures

On Kolkata’s trams, a journey through the city’s ‘soul’

Kolkata’s aging trams point toward a climate solution – but more importantly, for others, they also provide a reminder of a “simpler and slower” time.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Ahmer Khan Contributor

Kolkata’s electric trams don’t just take passengers through the city – they take them through time.

For about 15 rupees ($0.18), the trams offer a window into Kolkata’s past of colonial buildings, grand mansions, beautiful bookstores, and old markets. As passengers amble along, everything from savory street foods to traditional sweets is within arms reach.

Kolkata’s trams, which originated with horse-drawn rail systems under British rule, have spent recent decades atrophying, for lack of riders. But lately there’s been a resurgence of interest – among enthusiasts, and also climate activists.

“In a time of climate crisis, we need to embrace modes of transport that are sustainable and efficient,” says Debasish Bhattacharyya, president of the Calcutta Tramways Users’ Association.

For others, trams offer an irreplaceable ambiance – a mellow constant among a vibrant, changing city.

“I have been riding trams for as long as I can remember,” says Pranab Chakraborty, who is in his 70s. “It reminds me of my childhood, when life was simpler and slower.”

Click the deep read button to explore the full photo essay.

On Kolkata’s trams, a journey through the city’s ‘soul’

As electric trams slowly rumble through the vibrant neighborhoods of Kolkata, formerly known as Calcutta, they take the passengers on a journey back in time. Part of the cultural fabric of the city for more than a century, the tram system has been allowed to atrophy for a lack of riders. Now, enthusiasts and climate activists are fighting to keep tram service as an eco-friendly transportation option.

“Trams are a great way to reduce emissions in the city,” says Debasish Bhattacharyya, president of the Calcutta Tramways Users’ Association (CTUA). “In a time of climate crisis, we need to embrace modes of transport that are sustainable and efficient.”

The first horse-drawn trams appeared in the 1880s, during British colonial rule; next came steam-powered cars. Electrified trams arrived in the early 1900s. They were a popular and inexpensive means of travel.

“I have been riding trams for as long as I can remember,” says Pranab Chakraborty, who is in his 70s. “It reminds me of my childhood, when life was simpler and slower.”

For about 15 rupees ($0.18*), trams offer a window into the city’s past of colonial buildings, grand mansions, beautiful bookstores, and old markets. Traveling this way offers passengers an opportunity to sample local cuisine, from savory street foods to traditional sweets.

As Mr. Chakraborty puts it, “The trams may be old, but they are still an integral part of Kolkata’s soul.”

Editor's note: This photo essay has been updated to correct the U.S. dollar value of the tram fare. Fifteen rupees is the equivalent of $0.18.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Freeing the truth for freedom of the seas

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With so many official lies on social media, many more governments are getting better at pushing the truth. Ukraine, for example, has convinced most of the world – reflected in a United Nations vote last year – that, contrary to Kremlin claims, it was indeed invaded and is not led by neo-Nazis. Now the Philippines has followed suit with its own truth-telling campaign, one designed to expose China’s military aggression within the legal domain of Philippine waters and islands in the South China Sea.

Since February, after a Chinese ship used a military-grade laser to blind Filipino sailors on patrol in their own maritime territory, the government in Manila has taken journalists to see China’s swarm of ships – and frequent provocations – within the Philippine maritime zone. With video recordings, the Philippines can readily counter China’s fanciful claim that its control of islands 1,000 miles from its shores is merely peaceful.

In today’s globe-spanning digital universe, transparency is proving to be a defensive weapon. As a Philippine navy commodore states, “By continuing to document and publicize these [Chinese] incidents, the international community can build a strong case against China’s actions and potentially force it to alter its behavior.”

Freeing the truth for freedom of the seas

With so many official lies on social media, many more governments are getting better at pushing the truth. Ukraine, for example, has convinced most of the world – reflected in a United Nations vote last year – that, contrary to Kremlin claims, it was indeed invaded, that it is not led by neo-Nazis, and that the people of eastern Ukraine do not want to join Russia. In Scandinavia, state media just exposed how Russian spy ships have planned ways to sabotage underwater cables and wind farms in Nordic waters – contrary to disinformation from Moscow.

Now the Philippines has followed suit with its own truth-telling campaign, one designed to expose China’s military aggression within the legal domain of Philippine waters and islands in the South China Sea.

Since February, after a Chinese ship used a military-grade laser to blind Filipino sailors on patrol in their own maritime territory, the government in Manila has taken journalists to see China’s swarm of ships – and frequent provocations – within the Philippine maritime zone. A common provocation is Chinese vessels barring Philippine boats from their own waters. With video recordings, the Philippines can readily counter China’s fanciful claim that its control of islands 1,000 miles from its shores is merely peaceful.

Manila’s factual accounts have proven “to be a powerful tool in reshaping public opinion and debunking false narratives,” writes Jay Tristan Tarriela, a commodore in the Philippine navy, in The Diplomat. Talking to reporters, he said, “Chinese actions in the shadows are now checked, which also forced them to come out in the open or to publicly lie.”

Such truth-telling, along with Manila giving the U.S. military greater access to more bases, has clearly irked China, which seeks primacy in Asia over the United States. Beijing’s foreign minister will be in Manila April 21-23 trying to roll back the campaign against Chinese bullying and false narratives.

The Philippines already has much of the world’s support. In 2016, an international court invalidated China’s claim over almost all of the South China Sea, a claim that is clearly contrary to the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea. No other country has supported its interpretation of maritime law.

In today’s globe-spanning digital universe, transparency is proving to be a defensive weapon. As Dr. Tarriela states, “By continuing to document and publicize these [Chinese] incidents, the international community can build a strong case against China’s actions and potentially force it to alter its behavior.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘Be ye therefore perfect’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Raffles

Perfection may seem unattainable, but when we consider things through a spiritual lens, we discover more of the spiritual perfection God expresses in us – which brings healing.

‘Be ye therefore perfect’

Jesus told us, “Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father which is in heaven is perfect” (Matthew 5:48). But...perfection? Is that even remotely possible to attain?

When we look at the world today, things may look very far from perfect. Yet, every day we’re also aware of examples of refined achievement. We board airplanes engineered according to the laws of aerodynamics. We drive over bridges designed and built according to strict architectural precepts. Many aim to express honesty, fairness, wisdom, and genuine care in interactions with others.

But whatever the arena of life, it’s vital for humanity to strive toward, and ultimately adopt, the only true, perfect model of thought and action – one that flows from the ever-dependable intelligence that is divine Principle, God.

The Bible shows us that God is the source and basis of all perfection. For example, the book of Genesis establishes that man is created in God’s image and likeness, which means that each of us is fashioned from a model of complete perfection. Our role is to open our thought to understand this fact and accept how God has created us: spiritually perfect – good, intelligent, whole, and loving. As Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer and founder of Christian Science, wrote in her work “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “God is the creator of man, and, the divine Principle of man remaining perfect, the divine idea or reflection, man, remains perfect” (p. 470).

So, what are we to make of all the imperfection that confronts us every day – faulty bodies, discordant relationships, stalled progress, and so on? If we presume that the model – God – is in fact perfect, but that there is imperfection in what should be the expression of that model, then the problem must lie in our perceiving and accepting a different, faulty model.

Science and Health again sets forth the standard, the right basis: “The Christlike understanding of scientific being and divine healing includes a perfect Principle and idea, – perfect God and perfect man, – as the basis of thought and demonstration” (p. 259). It explains the importance of using the lens of spiritual sense – described here as “Christlike understanding.” In so doing, we base our thoughts and actions on the dependable, divine reality of God’s creation as opposed to a flawed material perspective or model.

When we hit a wrong musical note, we do not think the science of music has changed. We trust the consistency of musical principles and correct our misapplication of them. In our daily lives, rather than dwell on other types of “wrong notes,” it is helpful to turn our thinking to the underlying divine Principle.

Christ Jesus was the most effective healer the world has ever seen, because he perceived so clearly the identity of man as God’s offspring. Relying on the same divine Principle, we can today heal ourselves and others. Correct conclusions must logically proceed from an accurate premise. A primary basis of illness or dysfunction lies in accepting a model of man as a vulnerable mortal, whereas the true nature of each one of us is spiritual. For example, perfect health is, in reality, ours continually.

This has been proved in my family. For instance, during a two-week visit, our daughter-in-law had what appeared to be a large cyst on her foot. One night, my wife had an exceptionally strong sense of the purely spiritual nature of our daughter-in-law’s being. Beholding the perfect image of God expressed in our daughter-in-law left no room for a false, imperfect image.

By the next morning the cyst had dissolved. My wife had not been specifically praying to heal the cyst, but over the course of that visit had been praying to see the perfection of every family member. This healing was the natural and prompt outcome of beholding God’s perfect creation, man.

The framework of perfect God creating and maintaining man as His perfect expression is unaffected by any imperfection we see or feel through the material senses. Rather than a call to some unattainable goal, Jesus’ command to “be ye therefore perfect” can be understood as an admonition to acknowledge our present reality as created by God. Understanding that reality plants our lives on a sure foundation, and our experience will naturally express more of the good – the perfect good – that underlies all creation.

Adapted from an article published in the Nov. 28, 2022, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Suds for the Socialist

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Please come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a podcast episode with the Monitor’s Christa Case Bryant and Stephanie Hanes, who both brought a love of the outdoors to their recent climate-related cover story.

Also, we want to share an update on our format: We’ve changed the look of our photo captions in the Daily and on CSMonitor.com. Captions are now collapsed by default, allowing a smoother, simplified reading experience. To read a caption, click “view caption” under the photo. Let us know what you think. Email us at daily@csmonitor.com.