- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A young Iraqi’s efforts to rebuild his life and country

Husna Haq

Husna Haq

Twenty years ago today, President George W. Bush famously announced the end of major combat operations in Iraq aboard the U.S. aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln beneath a banner that declared “Mission Accomplished.” Of course, the war would drag on much longer, changing the lives of scores of U.S. troops – and deeply impacting a generation of Iraqis. Laith Louay is one of them.

Mr. Louay was born two months after the United States invaded Iraq in March 2003. He was 6 months old when U.S. troops killed his father, whose car was shot at en route to a medical appointment, and he was a toddler when American forces raided his house, looking for Al Qaeda fighters. When he was 11, the Islamic State group seized his town in Anbar province, forcing him to flee to Baghdad, stop his schooling, and sell corn from a street cart. Mr. Louay told his story to Al Jazeera as part of a collection of profiles.

The war orphaned 5 million Iraqis, killed about 200,000 civilians, displaced at least 4 million people, and devastated much of Iraq’s infrastructure, economy, and cultural heritage.

The human cost is impossible to quantify, says Alannah Travers, who interviewed Mr. Louay. “My impression ... was ... how unfair the implications of war are on the most vulnerable,” she told me. But remarkably, despite all he’s been through, Mr. Louay is not bitter, she says.

He is slowly rebuilding his life, and with it, his country. Mr. Louay returned home in 2017 to establish the Al-Khair Youth Team, a small organization whose volunteers, some of whom were orphaned by the war, provide food, activities, and basic lessons to youth. He returned to high school to get his diploma. Now, he dreams of marrying his fiancée, Sara, and starting a family, as well as expanding his organization and establishing a home and school for the children he serves.

“It is ... inspiring how he has been compelled to turn his adversity into action,” Ms. Travers told me. “He is a man of strong convictions.”

Mr. Louay has ample reason to act. “I don’t want people to live the same as I did,” he told Ms. Travers. “I want this country to be safe.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Bank failures put deposit insurance in spotlight

Recent bank failures in the United States have raised questions about whether a wider safety net of deposit insurance is needed – but also about how regulators can incentivize prudent behavior by banks.

Over the weekend, First Republic Bank, based in San Francisco, collapsed and was subject to a hastily orchestrated restructuring. JPMorgan Chase announced Monday that it had acquired most of First Republic’s assets from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and that branches would open as usual.

While the immediate drama has ended, FDIC insurance itself is under scrutiny. With three banks now felled by bank runs in the past two months, regulators are looking anew at the program that was created 90 years ago to discourage panic behavior by depositors. In fact, regulators have created a potentially big problem for themselves.

By using a loophole in March to guarantee all deposits at the first two failed banks, regulators may be hard-pressed to walk back such a commitment in future bank failures. Up to now, the FDIC has only guaranteed bank depositors up $250,000 per single account and $500,000 for a joint account. Many economists worry unlimited insurance will foster apathy among depositors – and thus encourage risky behavior by banks.

The FDIC on Monday released a report recommending a new “targeted” system where business accounts would receive higher insurance than individual accounts – rather than either insuring all deposits or sticking with the $250,000 cap.

Bank failures put deposit insurance in spotlight

Sue Hackney had heard the news, of course. When reports surfaced in March that First Republic Bank might be in trouble, the Boston-area marketing professional and her husband debated whether to pull their money out. But “their customer service is so good,” she says, so the couple waited.

Then last week, the San Francisco-based bank released its quarterly earnings, which showed it had lost more than a third of its deposits. Its shares, already deeply discounted, plunged again – in all, a stunning 97% fall in value in three months.

Busy at work and two days away from a trip out West, Ms. Hackney felt in no position to suddenly find a new bank. “We also figured the FDIC insurance is there,” she says. On Monday, JPMorgan Chase – the nation’s largest bank – validated her optimism. It announced it had acquired the substantial majority of First Republic’s assets from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and that First Republic’s branches would open as usual on Monday.

While the immediate drama has ended, easing fears about U.S. banks’ stability, FDIC insurance itself is under scrutiny. With three banks now felled by bank runs in the past two months, regulators are looking anew at the program that was created 90 years ago to discourage bank runs. On Monday, the FDIC released a report outlining three options. The problem is that its actions to calm markets may have foreclosed all but one of those options.

The FDIC report takes a detailed look at the pros and cons of keeping the status quo, moving to unlimited deposit insurance, or using what it calls targeted insurance. It recommends targeted insurance, where business payment accounts would receive significantly higher coverage than individual consumer accounts.

But regulators’ actions may speak louder than their words. By using a loophole in March to guarantee all deposits at the first two failed banks, regulators may be hard-pressed to walk back such a commitment in future bank failures. Up to now, the FDIC has only guaranteed bank depositors up to $250,000 per single account; $500,000 for a joint account. Many economists worry unlimited insurance would encourage risky behavior by banks and depositors, or what they call moral hazard.

“Unlimited coverage ... clearly cannot be the right answer. I mean, you can pretty much prove it,” says Eduardo Dávila, an economics professor at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and co-author of a 2021 study on optimal deposit insurance. “Unlimited coverage will require enormous amounts of regulation in a way we haven’t seen in 40 years.”

Bank stock and bond holders still do face risks of failure in the marketplace, even when deposits are protected.

But the conundrum is a real one: Too little deposit insurance could encourage more bank runs. Too much would require more oversight and rules by regulators to keep banks in line.

“They’re in a bit of a bind right now, unless all this settles down and in two months all is well,” Daniel Tarullo, an international financial regulation professor at Harvard and former member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, said last Wednesday in an online event at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “Are we saying we’re giving up entirely on market discipline?”

There’s too little market discipline in banking already, says Charles Calomiris, a Columbia Business School professor and former chief economist of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, another federal bank regulator. Some of the regulatory reforms in the aftermath of the savings-and-loan crisis of the 1980s and the financial crisis of 2008 have increased FDIC insurance and discouraged banks and big depositors from exercising some discretion in where they put their money. The predictable result, critics say: messes like the one at Silicon Valley Bank, which in March became the nation’s second-biggest bank takeover in history until First Republic Bank replaced it Monday.

In a sharply critical report released Friday, the Federal Reserve blamed Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse on a combination of the bank’s failure to manage interest-rate risk and the Fed’s own supervisors, who delayed too long before reacting to the growing signs of trouble. Silicon Valley Bank had grown rapidly by catering to high-tech startups in need of financing and by encouraging them to keep all their money at the bank, sums that often exceeded the FDIC’s $250,000 limit.

“How in the world could there have been so much in dumb uninsured deposits sitting at one bank?” Mr. Calomiris asks. “The answer is: That’s what deposit insurance did, ironically,” along with other regulatory changes.

In a separate report also released Friday, the FDIC blamed the failure of Signature Bank on mismanagement and said, in retrospect, its staff could have acted sooner. The bank also specialized – in this case, in the New York real estate market – and in 2018 began allowing customers with at least $250,000 on deposit to use cryptocurrency, a digital kind of money. As a result, many of its clients had accounts well above the FDIC limit.

First Republic was also heavily involved in real estate, offering jumbo mortgages to wealthy homeowners on the East and West coasts. When rumors of big withdrawals at Silicon Valley Bank began to circulate, fears about Signature and First Republic spread, leading many of their depositors to pull money out.

The underlying problem that exposed the flaws at these three banks is endemic to most banks to some extent. They make long-term loans, such as mortgages, but pay money out on short-term deposits. When interest rates on those deposits rise dramatically, banks can end up paying out more money on deposits than they’re making on loans, and their profits get squeezed. The 4 percentage point rise in interest rates in the past year has been the fastest since the 1980s.

Clearly, all three banks were operating without much of a safety net. The big question for regulators is whether those banks were the exception or whether regulators need to extend the safety net so other banks don’t come under pressure.

Monday’s FDIC report points to several trends that may be making the banking system more vulnerable to runs, such as the power of social media to quickly spread concerns about specific banks. Another problem is the rapid growth of uninsured deposits after the financial crisis, which grew from $2.3 trillion at the end of 2009 to $7.7 trillion in 2022. The problem is especially acute among the top 1% of banks, where just under a third of deposits were uninsured compared with 14% before 2020.

That means that a small group of big customers may quickly spark a panic. “Growing concentrations of uninsured deposits at large banks make the banking system potentially more vulnerable to depositor runs,” the FDIC report said.

Fighters from post-Soviet world flock to Ukraine’s side

What motivates foreigners to fight and die for Ukraine? Those from Chechnya, Belarus, and Georgia say their countries will never enjoy freedom or democracy unless Russia is defeated. And so Ukraine’s war is their war.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

People from around the world have joined the fight against Russia in Ukraine, but for those from Chechnya and former Soviet republics Belarus and Georgia, the stakes feel especially high: their own freedom.

The exact number of battalions and fighters of such origin has not been officially divulged. But testimony from commanders and soldiers suggests thousands have flocked to Ukraine driven by a sense of shared responsibility.

“Former Soviet Union countries have been captives of Russia for 70 years,” says Commander Mamuka Mamulashvili, who has some 1,800 men under his command, 65% of them battle-hardened Georgians.

In a Kyiv apartment used by Chechen fighters to store weapons and rest between front-line missions, French-speaking Maga says he would prefer to have the chance to decide his country’s future at the polls rather than fight in a foreign country. “We don’t want to kill anyone. But we want to be free,” he says.

“We need to stop Russian aggression,” says Tor, a stocky English speaker. “If we don’t do it today, it will never stop. And the stronger Russia gets, the smaller our chances of freedom.”

Fighters from post-Soviet world flock to Ukraine’s side

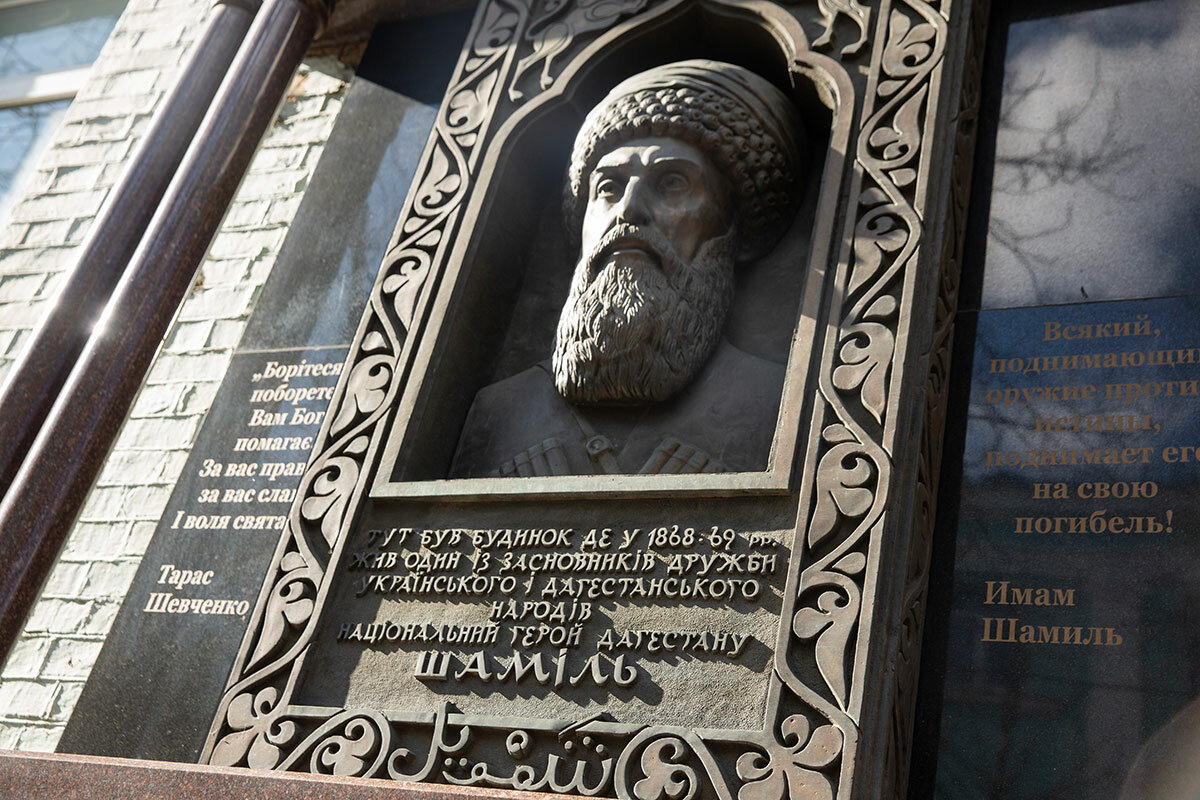

On Kriposnyi Lane in central Kyiv, captured Russian military vehicles stand in front of the National Museum of Military History. Just up the street, a bronze plaque affixed to a wall pays tribute to Imam Shamil, a 19th-century leader of the Caucasian resistance to the Russian Empire, and inspiration for subsequent Chechen resistance to Moscow’s rule.

The proximity of the two signs of defiance hints at a sense of common cause for fighters from across the post-Soviet world, thousands of whom have come to Ukraine’s aid since the Russian invasion.

“We need to stop Russian aggression,” says Tor, a stocky English-speaking Chechen fighter resting in Kyiv between rotations to the front line in Bakhmut. “If we don’t do it today, it will never stop. And the stronger Russia gets, the smaller our chances of freedom.”

People from around the world have joined the fight against Russia in Ukraine, but for those from Chechnya and former Soviet republics Belarus and Georgia, the stakes feel especially high. They say their countries will never enjoy freedom or democracy unless Russia is defeated in Ukraine. And so Ukraine’s war is their war.

The exact number of battalions and fighters of such origin has not been officially divulged. Ukraine’s Ministry of Defense and the Security Service both declined to answer questions on the subject. But testimony from commanders and soldiers suggests thousands have flocked to Ukraine driven by a sense of shared responsibility.

Among them is Cmdr. Mamuka “Ushangi” Mamulashvili, who heads the Georgian Legion of Ukraine. He has some 1,800 men under his command, 65% of them battle-hardened Georgians.

“The guys are very experienced,” he says with pride, speaking by telephone from an undisclosed front-line position in southeastern Ukraine. “They were prepared by NATO instructors. They can use NATO equipment. They can use post-Soviet equipment, and that makes them effective.”

“Former Soviet Union countries have been captives of Russia for 70 years,” Commander Mamulashvili says. “They are fighting against the same evil idea of communism.”

History of conflict

For post-Soviet peoples, the decision to fight in Ukraine is steeped in history – a history of conflict with Moscow since Russia forcibly absorbed Belarus, Georgia, and Chechnya into its empire in the 19th century.

More recently, Georgia had barely declared its independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union when Russia began bolstering would-be separatist regions of the new country. Moscow invaded Georgia in 2008, capturing Abkhazia and South Ossetia in an operation that foreshadowed the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Ukraine opened its doors to Georgian refugees in 2008, prompting a sense of solidarity and gratitude toward this country. Ukrainian volunteers also fought in Georgia against Russia in 2008.

“Ukraine did a great job to support Georgians, so naturally we are here to help,” Commander Mamulashvili says.

Fight for “a free Belarus”

Belarusian fighter Aleh Auchynnikau wears two knotted bracelets to indicate his allegiances. One is blue and yellow – the colors of Ukraine’s flag. The other is red and white – the flag of Belarus before it became a Soviet republic in 1919. That Belarusian flag – embraced by opponents of President Aleksander Lukashenko, a staunch Russian ally who has held power since 1994 – is banned in Belarus.

“There cannot be a free Ukraine without a free Belarus and there cannot be a free Belarus without a free Ukraine,” says Mr. Auchynnikau, a member of the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment (named for a Polish-Belarusian 19th-century revolutionary), which was formed in March 2022 and is made up entirely of Belarusian opposition volunteers.

Mr. Auchynnikau fought alongside the Ukrainian army against Russian-backed separatists in the eastern region of Donbas nine years ago. Later he joined a group of Belarusian fighters who regularly trained together in the forests outside Kyiv, driven by the sense that a larger conflict with Moscow was inevitable.

The Belarusian regiment is less experienced in warfare than its Georgian counterpart, but “we have huge motivation,” says Mr. Auchynnikau, sitting in a classroom used for tactical training in a Kyiv building provided by the Ukrainian government to Belarusian fighters. “We know why we are here. We were not conscripted. It is a call from the heart.

“The only reason Lukashenko is in power is because Putin supports him,” he goes on. “If we defeat Putin here, Lukashenko will not have his support and will be discarded. We want to go back to a free Belarus. Helping Ukraine is our direct road home.”

Since Moscow’s invasion, Mr. Auchynnikau has fought in the battles for Kyiv, Kherson, and most recently Bakhmut. It was there that he celebrated his recent birthday – its cold muddy moments captured in selfies – as he gulped down morsels of pizza and cake between incoming mortar rounds.

The Belarusian government’s close ties with Moscow complicate Belarusian volunteers’ efforts to join the fight in Ukraine. On the one hand, President Lukashenko’s security forces seek to track down potential combatants; on the other, Ukrainian security forces are suspicious of would-be fighters.

Ukrainian officials and Belarusian “cyber-partisans” vet potential recruits who apply through a chatbot on Telegram, an encrypted communications channel. “The screening is very serious and thorough,” says Mr. Auchynnikau. “They found three people who were agents of the Belarusian KGB.”

Chechen against Chechen

The Chechens fighting with Ukrainian forces are in a particularly unusual position: Their ancestors were subdued and absorbed into the Russian empire in 1859, after a 30-year war; had to be re-subdued by the Bolsheviks after the Russian revolution; and fought two wars against Moscow in the 1990s.

“Cooperation between Chechens and Ukrainians goes back to the 19th century,” says Dmytro Makhtarov, a researcher at Ukraine’s National Museum of Military History. “The destinies of these nations have one thing in common. They were occupied and invaded by the Russian Empire.”

Yet now those continuing the battle against Russia alongside Ukrainian troops find themselves up against other Chechen troops, loyal to Chechen strongman and close Putin ally Ramzan Kadyrov.

“Both sides hate each other and see each other as traitors who betrayed the idea of the nation,” says Mr. Makhtarov.

For young Chechens, he says, the war in Ukraine offers an opportunity to gain the kind of military experience their elders earned in the two Chechen wars against Moscow, or more recently in Iraq and Syria, where some Chechens fought with radical Islamist groups.

Some of the Middle East conflicts’ veterans are known to have made their way to Ukraine, although Mr. Makhtarov insists “Chechens who come to Ukraine get screened by our security services.”

In a Kyiv apartment used by Chechen fighters to store weapons and rest between front-line missions, Tor and his French-speaking comrade Maga, who both belong to the Dzhokhar Dudayev Chechen Peacekeeping Battalion, are not shy of voicing their ambitious goals.

Donning a balaclava before posing for a photo, Maga says he would prefer to have the chance to decide his country’s future at the polls rather than fight in a foreign country. “We don’t want to kill anyone,” he says. “But we want to be free. I’m sure that when Ukraine wins this war, Russia will collapse.”

“We fight here today so we don’t have to fight tomorrow in my country,” adds Tor.

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this story.

Is nuclear power attractive or risky? In Minnesota, it’s both.

In the Minnesota legislature, views on nuclear power once cleaved largely along party lines. Now climate change is shifting that pattern, but a radioactive leak has rekindled public concerns about safety.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Usually, this boat landing in a park along the Mississippi River is a popular spot to fish for bass and walleye.

But after a nearby nuclear plant announced that radioactive material had leaked twice from a faulty pipe since November, some locals here in Monticello, Minnesota, say they’re worried about what’s in the water.

“I’ll definitely be fishing upstream this year,” says Chuck, a resident whose father worked at the plant.

Building public trust is a key challenge for advocates of nuclear energy here and across the nation. With the exception of one next-generation plant in Georgia, the U.S. reactor fleet is of a similar generation to the one involved in Japan’s Fukushima disaster.

But as more states adopt ambitious clean-energy goals – Minnesota’s is to be 100% carbon-free on electricity by 2040 – many leaders say they can’t get there without nuclear power as part of the solution. One bipartisan bill here would fund research into the use of advanced nuclear reactor designs.

“As we’re looking at how you build a low- or zero-carbon economy, nuclear seems like an essential tool,” says Kevin Pranis of the Minnesota and North Dakota branch of Laborers’ International Union of North America, which represents over 12,000 workers.

Is nuclear power attractive or risky? In Minnesota, it’s both.

At a clearing in the brush, a clunky wooden dock is still pulled onshore for the season amid piles of dirty snow. Usually, this boat landing at the Montissippi Regional Park is a popular spot for amateurs to fish bass and walleye from the Mississippi River.

But after the Xcel Energy nuclear plant – just half a mile away – announced in March that radioactive material had leaked twice from a faulty pipe since November, some locals say they’re worried about what’s in the water.

“I’m more reluctant to put my line in the river now. I don’t know if it’s safe,” says Chuck, a Monticello resident who came to the park to play disc golf with friends. Chuck’s father worked at the nuclear plant for decades before leaving on bad terms (and for this reason, the son declines to give his last name). “I haven’t taken the boat out yet this season, but I’ll definitely be fishing upstream this year.”

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Minnesota Department of Health say the risks to the public from the leaks of water contaminated with tritium – totaling a little more than 400,000 gallons – are minimal and have not affected public drinking water. Xcel Energy powered down its Monticello plant in mid-March for maintenance, once the second leak had been discovered.

That has done little to assuage the fears of local residents, however, who say the utility company should have notified the public earlier about the leak.

As Minnesota joins a growing number of states with ambitious clean-energy goals – it recently passed legislation to go 100% carbon-free on electricity by 2040 – more climate advocates and politicians are saying they cannot get there with traditional renewables alone. That’s prompting a renewed push for nuclear energy, even among former skeptics. Yet building public trust remains a key challenge, in Minnesota and across the nation – particularly in the wake of incidents like the one in Monticello.

“Right now, there isn’t a single cheap, reliable renewable energy. Each of the technologies has its strengths and weaknesses,” says Kevin Pranis, marketing manager for the Minnesota-North Dakota branch of Laborers’ International Union of North America, which represents over 12,000 workers. “As we’re looking at how you build a low- or zero-carbon economy, nuclear seems like an essential tool.”

Reliance, but also restrictions

The U.S. gets approximately 19% of its electricity from nuclear power, according to the Energy Information Administration. While states need to go through the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) for licensing approval, much of the challenge of building nuclear energy plants or considering new nuclear technologies is getting past state legislation.

Minnesota – which gets 24% of its electricity from two nuclear power plants – is one of 12 states that currently have a moratorium on the construction of new nuclear power facilities. That has led proponents here to focus their efforts instead on the latest technologies, like small modular reactors – which have a smaller physical footprint than conventional reactors and are seen by many as the future of nuclear energy, based on cost and relative safety.

“We’re being technologically agnostic,” says Democratic state Sen. Tou Xiong. “We want to take a wide approach and look at ways to reach our climate goals, given what we have. And we do have nuclear power here in Minnesota.”

Senator Xiong is part of a bipartisan group backing a bill – which he hopes will pass this month – that puts $300,000 toward research on the environmental and health impacts, costs, and energy benefits of advanced nuclear reactor designs. He says that in the past five years, more Minnesota Democrats have come around to the idea of nuclear energy – an issue that once split along party lines.

This mirrors a wider national trend. In 2023 alone, there have been close to 100 bills across 20 states to repeal moratoriums or study nuclear energy, according to the Nuclear Innovation Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. The U.S. Department of Energy recently invested nearly $2 billion in TerraPower’s construction of a nuclear reactor in Kemmerer, Wyoming, to replace a retiring coal plant. And John Kerry, the special presidential envoy for climate, has openly supported nuclear energy as a tool to fight climate change.

“When we’ve done clean-energy modeling, the first 60% or 70% of decarbonization is fairly straightforward,” says Patrick White, project manager at the alliance. “But to reach more than 80% or 90%, balancing out your energy system gets a lot more challenging. ... It’s about what makes sense for each state and how serious we are about hitting our climate goals. What works in Florida may not work in Minnesota.”

Evolving concerns on safety

That’s not to say there aren’t concerns about nuclear from within the climate advocacy community. With the exception of the Vogtle plant in Burke County, Georgia – which boasts next-generation technology – the U.S. reactor fleet is of the same or similar generation as the one involved in Japan’s Fukushima disaster in 2011.

“Whether they’re identical in design or not, they all have the same level of vulnerability,” says Edwin Lyman, a physicist and the director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a national watchdog.

He says that nuclear plants always emit some radiation under normal operations, but this is regulated by the NRC.

“You could argue whether those limits are in the right place, but they’re designed to keep the level of harm below a certain threshold. The most serious risk to the public comes from those catastrophic events, like Fukushima, which are low probability but no one can say how low. How safe is safe enough?”

Dr. Lyman says the Biden administration, in its enthusiasm to tackle carbon emissions and roll out new nuclear plants, must be careful not to forgo needed safety rules. That becomes even more essential as climate change brings higher winds and flooding, the biggest risks for a reactor short-circuit. Nuclear operators have also struggled with how to store waste long term. New waste is stored in pools before being transferred to dry casks, which can take up land space indefinitely.

But to climate advocates who support nuclear, innovation inspires hope.

“I think people are coming to the conclusion that we have a long way to go [in meeting our clean-energy needs],” says Eric Meyer, the executive director of Generation Atomic, a nonprofit in Minnesota’s state capital, St. Paul. “We can’t put all our eggs in one basket.”

Mixed feelings by the Mississippi

The public seems to be on board with putting more time and research into nuclear energy. According to an April Gallup poll, 55% of Americans support nuclear energy, the highest level in a decade.

But for those living near nuclear plants, there are still concerns about safety and security – from the quality of groundwater to the threat of domestic terrorism. Out on the trail at Montissippi Regional Park in Monticello, locals joke that their tomatoes are extra large thanks to their proximity to the Xcel plant. Others say they’ve been drinking bottled water since the leak.

“When those Chinese surveillance balloons flew overhead [in February], I did wonder, would the nuclear plant be a target?” says Betty, out for a walk with her husband Jack. Betty used to work for the city of Monticello and did not want to identify herself by her full name.

While the immediate risks may be small, she says she and her husband “live in the shadow of the nuclear plant,” which is a half mile from their house. Every year, Xcel Energy distributes a free calendar, which includes evacuation information in the event of disaster.

To get beyond fear and misinformation, Xcel Energy held two community meetings last month in Monticello in the wake of the tritium leak, in hopes of bridging the communication gap – now and in the future.

“We’re having a dialogue with the city to figure out how to provide less mystery,” says Chris Clark, the president of Xcel Energy Minnesota, South Dakota, and North Dakota. “And in the event that something happens, how to explain what’s happening at the plant without creating unnecessary concern.”

A few miles down from the park at the Monticello Community Center, locals say they’re more preoccupied by politics and issues like artificial intelligence than nuclear energy. But the Xcel plant is never far from thought.

“I live upstream so I’m not that worried,” says Karen Hanson, from neighboring Albertville. “But if I lived downstream, I might think differently.”

Her friend Alice Kantor, who lives across the road from the Xcel plant, says she isn’t adamantly for or against nuclear energy and would welcome more information about it from local leaders.

“I’m always for advances,” says Ms. Kantor, running the table at a Sunday breakfast fundraiser for the Monticello Senior Center. “If nuclear is the best thing, then we should pursue it.”

In California, auto shop class is turning electric

Innovation requires ingenuity. This border-town high school is revving up students for an EV workforce. It’s an effort well suited to California’s green technology goals.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The scene at Calexico High School, a mile north of the California-Mexico border, might resemble a typical auto shop class. Except when this car comes to life, it won’t spew fumes.

It’s an electric vehicle.

The class complements the state’s vision of having all sales of new cars and light trucks be zero-emission vehicles by 2035. It’s part of a pilot project, funded by the California Energy Commission, to upskill students for a clean-energy workforce the state hopes to expand.

Auto shop teacher Keith Fisher says he’s preparing his students not only for possible work in the EV industry, but also for the know-how to maintain their own gasless cars. A day may come, he muses, when these students’ children may not even know what an internal combustion engine is.

“The technology is progressing so rapidly,” says Mr. Fisher.

But the class is also aware of some of the unsolved problems of so-called green technology. Solar panels present recycling issues, Andrew Chong offers as an example, and some people dislike wind turbines for ruining their views.

Yet Andrew, undaunted, sees himself as part of the solution.

“My goal is to maybe have an energy source, a new energy source, that does not have any negatives,” he says.

In California, auto shop class is turning electric

It’s a snake pit of wires, but the teens have it under control. Clad in navy coveralls, they’re checking voltage levels on a vehicle circuit board. Why won’t the right-side brake light work?

“We’re just trying to see, like, what the problem is,” says high school senior Nicholas Leon, focused on the multimeter in his grip.

The scene at Calexico High School, a mile north of the California-Mexico border, might resemble a typical auto shop class. Except when this car comes to life, it won’t spew fumes.

It’s an electric vehicle – an EV – that runs on batteries.

The class complements the state’s vision of having all sales of new cars and light trucks be zero-emission vehicles by 2035. It’s part of a pilot project, funded by the California Energy Commission, to upskill students for a clean-energy workforce the state hopes to expand.

The need for EV-savvy autoworkers was implied in an announcement by Gov. Gavin Newsom on April 21. Two years ahead of schedule, the state has surpassed 1.5 million new zero-emission vehicle sales, though affordability and charging infrastructure issues remain. For California, zero-emission vehicles include battery electric, fuel cell electric, and plug-in hybrid vehicles, which, together, comprised nearly a fifth of all new cars sold here in 2022.

Several seniors in the class show an interest in EV-related careers, though the hands-on electrical and troubleshooting skills are useful tools no matter their path. Advocates hope that by training young talent for “green” jobs in the region, students will see themselves in the driver’s seat of local ingenuity and innovation.

“We have to be able to make sure that by the time they graduate and they choose their career path, that it’s here,” says Luis Olmedo, executive director of Comite Civico del Valle, an environmental justice group.

Historically, says Mr. Olmedo, students have wanted “to leave, because the only option is to go work in the fields” of Imperial Valley.

“We have to change that mindset,” he says. “There’s so much potential here.”

Preparing for the future

Calexico Unified School District sits in California’s arid southeast. Nearly all 8,300 students are Hispanic.

The city, with some 40,000 people, witnesses a mix of billion-dollar agriculture, rural poverty, and an international border that many drive across daily. Transportation, which contributes around half of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, is one sector targeted to help California reach “carbon neutrality” by 2045, with EVs playing a critical role.

Auto shop teacher Keith Fisher says he’s preparing his students not only for possible work in the EV industry, but also for the know-how to maintain their own gasless cars. A day may come, he muses, when these students’ children may not even know what an internal combustion engine is.

“The technology is progressing so rapidly,” says Mr. Fisher. The longtime educator and surfer from Hawaii, who renovates old cars as a hobby, had to teach himself how EVs work.

“Once you can understand electricity and how it flows … it’s pretty straightforward,” he says.

The class assembles a two-seater sand rail, from the California company Switch Vehicles, that runs on batteries alone. A lead-acid battery pack that looks like a big, black brick sits in the front. Mr. Fisher is expecting to receive a lithium-ion EV, which is more common, from the state this year, along with a conversion kit and other resources. His auto shop curriculum has a two-year track: Juniors learn the basics, the EV comes in senior year. Students can earn credentials in both.

Trying not to get too far ahead of the curve

After a pandemic delay, this is the second fully in-person year students are working with an EV kit. The hands-on experience is a boon for Andrew Chong, who says the pandemic “really hit me hard” and canceled his plans to partake in a STEM competition.

“My future in EV is a future where there’s no disposable batteries,” the student says during a February class. “They’re not that good for the environment.”

These students “understand the environmental imperative. They understand the economic return for a career in this space. And they’re not just limited to the occupations of service maintenance,” says Larry Rillera, an air pollution specialist at the California Energy Commission.

Since 2017, his agency has spent $3.5 million for the Zero Emissions Vehicle High School Pilot Project, working in collaboration with the Advanced Transportation and Logistics Center at Cerritos College in Los Angeles County. The funds have supported EV curricula at 52 high schools in disadvantaged and low-income communities. Calexico High is the only campus in Imperial County.

The district has begun to acquire EV buses, which, along with positions at dealerships and other auto shops in Calexico, creates a need for skilled technicians, says Mr. Rillera. And auto shop teacher Mr. Fisher says he’s discussing potential partnerships with regional and national companies.

It’s important to ensure there are jobs awaiting students in this space, says Jane Oates, president of WorkingNation, a nonprofit media organization. As a former U.S. Department of Labor official during the Obama administration, she recalls being part of a federal movement that funneled funds to job training for wind turbines and solar panel installation. It was a lesson learned about being ahead of the curve.

“We put a lot of money out there, and trained a lot of people to be technicians in those two areas, and there were no jobs” at the time, she says. It helps that Mr. Fisher is “embedding this in a traditional program so kids are graduating with traditional auto-mechanic skills.”

Several Calexico students interviewed do desire a career in a car-related field, with or without EVs. As the Calexico Chronicle reports, some plan to pursue trade school first.

“I really want to be a mechanic,” says Orlando Alatorre. “I know that EV is very game-changing for the auto industry, and I would love to learn more.”

Armando Villaman, on the other hand, sets his sights on U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

“I want to learn, like, how to dismantle cars,” he says, to search for stuff like drugs.

Students in the class are also aware of some of the unsolved problems of so-called green technology. Solar panels present recycling issues, Andrew offers as an example, and some people dislike wind turbines for ruining their views. Both forms of renewable energy have been introduced to this region in recent years – not without community pushback.

Andrew, undaunted, sees himself as part of the solution.

“My goal is to maybe have an energy source, a new energy source, that does not have any negatives,” he says.

Getting a stubborn brake light to work

Many of these future innovators are most comfortable speaking Spanish, says Mr. Fisher, who teaches in English. He posts large handwritten notes on a classroom wall with tips for phrasing questions (“May I please – ?”) as well as upbeat axioms. One evokes a boat analogy.

“Don’t let what’s happening around you get inside you and sink you,” it reads.

The emphasis on problem-solving continues in the garage next door, where a huddle has formed around the stubborn brake light. Twenty minutes of testing have passed, and the teacher has joined. A loose wire is rejiggered and then ...

The light glows red.

“Whoo!” someone rejoices. “Yay!”

Next challenge, however, is how to turn it off.

“I’ll let them play with that,” says Mr. Fisher. “It can be frustrating. But … you learn through the process.”

The EV is up and running, the teacher reports. Before it’s deconstructed, the teens get to take it for a spin around a parking lot.

In Pictures

For blind musicians, Khmer culture sings

Traditional arts were crushed under the Khmer Rouge. But a school for orphans helps pass musical and poetic traditions down to future generations.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Oscar Espinosa Contributor

-

Laura Fornell Contributor

Along one of the quiet avenues of Kampot, in southern Cambodia, the stillness imposed by the afternoon heat is broken by music escaping from a classroom.

Chourn Reach sets the melody with his tro, a two-stringed, bowed instrument; Saron takes up the takhe, a kind of three-stringed floor zither in the shape of a crocodile; Iem Rokhthai plays a kind of flute called khloy; and Kan Prak is in charge of percussion with the skor, made up of two small drums.

All are blind.

The small ensemble rehearses at the Khmer Cultural Development Institute (KCDI), a nongovernmental organization that emerged in 1994 to care for orphaned children and preserve traditional arts. Many of these arts are in danger of being lost in the years since the Cambodian genocide perpetrated by Maoist Khmer Rouge. But for three decades, hundreds of children have found refuge and training here.

Someday, these students will be the ones passing down the traditions – the same ones “the Khmer Rouge wanted to destroy,” Mr. Samoeun says.

“This is the time of the day I enjoy the most,” Saron says.

The others nod in agreement.

Click the deep read button to explore the full photo essay.

For blind musicians, Khmer culture sings

At 3:00 in the afternoon, the intense heat in the quiet city of Kampot, in southern Cambodia, makes the streets practically deserted. Along one of the avenues, music from a classroom escapes into a garden. Inside, four students – all of whom are blind – practice with deep concentration.

Chourn Reach sets the melody with his tro, a two-stringed, bowed instrument; Saron occupies a large part of the music room with a takhe, a kind of three-stringed floor zither in the shape of a crocodile; Iem Rokhthai plays a kind of flute called khloy; and Kan Prak is in charge of percussion with the skor, made up of two small drums.

“This is the time of the day I enjoy the most,” Saron says, sitting in front of his instrument. The others nod in agreement.

The small Mohori music ensemble – Mohori is a type of traditional Khmer music – rehearses at the Khmer Cultural Development Institute (KCDI), a nongovernmental organization that emerged in 1994 to care for orphaned children and preserve the traditional arts. Many of these arts are in danger of being lost in the years since the Cambodian genocide perpetrated by Maoist Khmer Rouge. For three decades, hundreds of children have passed through the KCDI, where they have found refuge and training. Many have gone on to become professional artists. The center currently houses 10 orphaned children between the ages of 5 and 17, as well as the four musicians, who range in age from 17 to 24.

“It gives me great pleasure to transfer my knowledge to these youths and to think that they will continue to preserve the traditional Khmer arts,” says their teacher, Ros Samoeun. After surviving a Khmer Rouge prison camp, he became a professor at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh and in 1997 joined the KCDI project.

Two of the older youths dropped out of school to study music full time, and a third is preparing to become a lawyer. The youngest, Kan, goes to the public school every morning, where he attends sixth grade and learns to read Braille. Kan is passionate about reciting smot poems, also known as Cambodian Buddhist chanting. Smot is usually performed at funerals by a solo singer. Its poetic texts often refer to the life and teachings of the Buddha, traditional Khmer stories, and religious and moral principles such as gratitude to parents and elders.

“It is very important to perpetuate smot and [ensure] that this centuries-old genre that the Khmer Rouge wanted to destroy ... does not disappear,” says Mr. Samoeun. “Although [the youths] still have a lot to learn, they will be in charge of transmitting this traditional musical, social, and liturgical expression to the next generation.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A May Day of mental liberation in Cuba

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Authoritarian regimes seldom pass up opportunities for extravagant patriotic pomp. So when Cuba’s leader, Miguel Díaz-Canel, canceled the May Day celebrations in Havana today for only the third time since 1959 (the first two times were during the pandemic), the move begged the question why.

The Cuban president blamed acute fuel shortages caused by U.S. sanctions. But the real reason may be something deeper – the people’s demand for freedom in response to severe economic crisis and repression. As one Cuban tweeted about the decision: “Good idea. An expensive celebration makes a mockery of the people in a time of shortages. Just get on the streets & shout what you really think!”

This mental liberation – and the government’s fear of it – is increasingly evident in this communist dictatorship. Since Mr. Díaz-Canel rose to power in 2018, his tenure has been marked by economic decline and iron-fisted intolerance.

Those who have stayed are pushing back. Voter turnout plummeted in the largely meaningless municipal elections last November. One in four abstained in the parliamentary ballot in March.

A May Day of mental liberation in Cuba

Authoritarian regimes seldom pass up opportunities for extravagant patriotic pomp. So when Cuba’s leader, Miguel Díaz-Canel, canceled the May Day celebrations in Havana today for only the third time since 1959 (the first two times were during the pandemic), the move begged the question why.

The Cuban president blamed acute fuel shortages caused by U.S. sanctions. In years past, the government has bused in millions of workers from the hinterlands to pack the capital.

But the real reason may be something deeper – the people’s demand for freedom in response to severe economic crisis and repression. As one Cuban tweeted about the decision: “Good idea. An expensive celebration makes a mockery of the people in a time of shortages. Just get on the streets & shout what you really think!”

This mental liberation – and the government’s fear of it – is increasingly evident in this communist dictatorship. Since Mr. Díaz-Canel rose to power in 2018, his tenure has been marked by economic decline and iron-fisted intolerance. Food prices have soared, the currency has tumbled, and inflation hovers at 200%. A new penal code criminalized dissent. Roughly a third of the population has tried to emigrate since late 2021.

Those who have stayed are pushing back. Voter turnout plummeted in the largely meaningless municipal elections last November. One in four abstained in the parliamentary ballot in March that gave Mr. Díaz-Canel a second term (a foregone conclusion, since opposition candidates were barred from the ballot). Cubans turned out in mass protests in July 2021 over the government’s mishandling of the pandemic, and then again last fall over acute electricity shortages.

In a country long shaped by collectivist thinking, hardship is forging new racial unity as Cubans seek refuge in the country’s unique blend of African spirituality and Catholicism. Santería, as it is called, is “so decentralized and it allows the individual believer or practitioner to make it what they need it to be,” Katrin Hansing, an anthropologist in Cuba for City University New York, told The Associated Press last month.

Mothers have become another source of political resistance amid the shortages of daily needs, filling a space left open by the government’s repression of opposition parties. “Mothers feel the effects that certain policies or certain government inaction might have on their children,” said Amelia Calzadilla, who ignited a movement with a Facebook video asking the government to run a gas line to her block in Havana, in an interview with Al Jazeera.

The odd stillness in Revolution Square on May 1 isn’t the only sign that the government feels the pressure of discontent. In March, for the first time, it let Cuban baseball players who emigrated to the big leagues in the United States play on the national team at the World Baseball Classic.

That concession sent a signal that the aspirations of ordinary Cubans may be stronger than the regime’s tools of repression. “A country needs to be a place where people can have a beautiful life,” said Beatriz Luengo, director of a new documentary about “Patria y Vida,” a hip-hop song that has become an enduring anthem of change since the 2021 demonstrations. The title, “Country and Life,” is a play on the ruling Communist Party’s slogan “Country or death.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Financial issues? Help is always at hand.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

When finances seem vulnerable or meager, recognizing that God is always with us – giving us endless good – reveals solutions, sometimes in ways we don’t expect.

Financial issues? Help is always at hand.

Managing finances can feel like a stressful process – especially when there doesn’t seem to be enough. Christian Science offers an encouraging view, one that shows God to be the perfect source of everything we need, without partiality, and us to be His spiritual offspring, forever supplied and satisfied.

Setting aside a limited view of finances for a deeper trust in our reliable God has tangible effects. We’ve selected a few articles from the archives of The Christian Science Publishing Society that share inspiration on this topic and accounts of how individuals, families, and businesses facing scarcity found God’s goodness to be right at hand.

The author of “The ‘stimulus package’ that lasts” shares how following Jesus’ instruction to seek God’s kingdom first and foremost was a solid starting point for solutions after he found himself in deep financial trouble.

When a couple lacked resources to pay the fees for their daughter to attend school, turning to God brought inspiration and the needed supply “swiftly without obstacles,” as the author of “God met our family’s needs” relates.

“The powerlessness of lies” considers that we all have a God-given ability to do the right thing, without being left hanging – as a man experienced after emptying his bank account to pay some overdue bills.

“Prayer can resolve economic hardship” explores the idea that even in what seem to be dire situations, leaning on God’s will instead of our own agenda leads to progress, as a woman found when her family’s business was in danger of bankruptcy.

The author of “God’s goodness is unlimited” only had enough funds to pay one of two important bills. The idea that God’s goodness is endless lifted her fear and brought peace – and a surprising source of income enabled her to pay both bills on time.

In “Turning to God meets all needs,” the author shares ideas about spiritual supply that helped him let go of the worry and guilt he felt because his income wasn’t meeting his family’s needs, and find practical solutions.

Viewfinder

‘Bring in the May’

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Please come back tomorrow, when we’ll have a profile of former Gov. Nikki Haley as she campaigns for the GOP presidential nomination in Iowa.