- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

George Santos, an indictment, and democracy’s resilience

In 2002, Democratic Rep. James Traficant of Ohio was expelled from Congress after a 10-count felony conviction on charges including racketeering and the filing of false tax returns.

Today, it’s Republicans grappling with the alleged criminal behavior of one of their own, Rep. George Santos of New York. The first-term member of Congress – already infamous as a serial fabulist about, apparently, pretty much every facet of his life – was indicted Tuesday and turned himself in Wednesday. He has pleaded not guilty to 13 criminal counts of wire fraud, money laundering, theft of public funds, and making false statements to the House of Representatives.

A summary of the federal charges can be read here. The most serious charge, wire fraud, carries a maximum sentence of 20 years.

Representative Santos admitted months ago to “embellishing” his résumé and told British TV host Piers Morgan that he’s a “terrible liar.” But owning up to lies is one thing. Now he’s in legal jeopardy, and the stakes are much higher.

For Mr. Santos’ constituents, and for Congress itself, it’s a sad moment. Mr. Santos has long withstood calls to resign – including from many Republicans – and faced countless jokes. He has also already declared for a second term. If convicted, he could legally continue to serve from prison.

The moment presents a test for the narrow House GOP majority. When Representative Traficant was convicted in 2002, the House voted to expel him three months later. The expulsion of a convicted Mr. Santos would mean an even narrower Republican majority, and then a strong possibility he’s replaced by a Democrat – either in a special election or in the 2024 general election.

The whole Santos episode is an embarrassment – for the Republican Party, for his voters, for the major news outlets that didn’t pick up on the local reporting that raised important allegations long before Election Day.

Still, it points to the resilience of American democracy. While sitting in prison, Mr. Traficant ran for his old seat – which he was allowed to do – and lost with 15% of the vote. The voters had a choice, with full disclosure.

Now, in a court of law, a jury of Mr. Santos’ peers can decide his legal fate. But his political fate may already be sealed.

“The sooner he leaves,” New York GOP Rep. Nicole Malliotakis said in a statement, “the sooner his district can be represented by someone who isn’t a liar and a fraud.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

At Ukrainian training ground, a growing confidence

Ukrainian forces training for the critical spring counteroffensive know what they lack and need, but also what they have. Among their assets is growing confidence.

As the Ukrainian military, bolstered by American and European hardware and cash, prepares for its much-heralded spring offensive – an assault it hopes will reclaim Russian-occupied territory – training grounds some miles back from the sprawling Donbas front lines are seeing the use of every tool.

Across a muddy hilltop carpeted by spent shell casings, elements of multiple brigades train on an array of weapons, old and new. Soldiers line up to take turns firing two new Czech-made light machine guns that are unwrapped in the sunlight, their parts glistening with factory oil.

Yet three grenade launchers here are clearly inherited from former Soviet stockpiles and stamped with the years 1975, 1982, and 1986, when they would have seen duty during the Cold War, or in Afghanistan, where they first became popular with Soviet infantry.

A key source of confidence for Ukrainians, despite the challenge to come and their limited means and hardware, is that at this point of the war, they know the weaknesses of their enemy – and appreciate their own capabilities.

“We are very optimistic,” says a bald soldier who gives the name Vitalii. “Even without American weapons, even with this old stuff, we are kicking Russian [tails]. With the American guns, the Russians don’t have a chance.”

At Ukrainian training ground, a growing confidence

From the sudden renewal of Russian missile barrages on Kyiv and other cities to Ukrainian strikes behind Russian lines, signs are multiplying that both sides are gearing up for Ukraine’s critical spring counteroffensive.

Yet even as some analysts suggest that such deep Ukrainian strikes, including in long-occupied Crimea, signal the offensive has already begun, Ukraine is patiently and deliberately rotating front-line forces for training to equip them for the main push to come.

Among the Ukrainian troops, their work on these proving grounds appears to amplify a sense of confidence, rather than foreboding.

At one recent session, on an eastern Ukrainian practice range marked by rolling hills, spring sun, and distant targets obliterated by firepower, a bald Ukrainian soldier who gives the name Vitalii enthuses about old 30mm grenade launchers mounted on tripods. They’re so old they could have been used by his father during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s.

“This is very effective; three men can stop 16 or 17 men,” Vitalii says. The launcher requires careful targeting and has a rudimentary trigger mechanism, as his fellow soldiers demonstrate by firing multiple rounds into a hillside.

Everyone within seven meters of an impact will be killed, says Vitalii, while everyone beyond that up to 10 meters away will be wounded.

As the Ukrainian military, bolstered by American and European hardware and cash, prepares for an assault that it hopes will reclaim lost territory – and ultimately force Russia out of Ukraine – these training grounds some miles back from the sprawling Donbas front lines are seeing the use of every tool.

Across a muddy hilltop carved with the treads of armored vehicles and carpeted by spent shell casings, elements of multiple brigades train on an array of weapons, old and new. A key source of confidence for Ukrainians, despite the challenge to come and their limited means and hardware, is that after 14-plus months of war they know the weaknesses of their enemy – and appreciate their own capabilities.

Indeed, the three AGS-17 grenade launchers here are clearly inherited from former Soviet stockpiles and stamped with the years 1975, 1982, and 1986, when they would have seen duty during the Cold War, or in Afghanistan, where they first became popular with Soviet infantry.

Soldiers also practice firing an 82mm gun mortar, another Soviet relic that first came into service in 1970.

“We are very optimistic,” says Vitalii, as the sound of rifle shots and explosions creates a steady background noise. “Even without American weapons, even with this old stuff, we are kicking Russian [tails]. With the American guns, the Russians don’t have a chance.”

The United States has been the leading Western supplier of Ukraine’s war effort against Russia. It has provided tens of billions of dollars’ worth of military equipment to defend Ukraine, and money to keep its economy afloat, in a battle that U.S. and European leaders cast as a pivotal historical fight.

In Russia, President Vladimir Putin presided Tuesday over the annual Victory Day parade, which commemorates the Soviet defeat of Nazi Germany. The event was shorter and far less immense than it has been in previous years – with just one World War II-era T-34 tank, instead of the usual row upon row of modern Russian tanks – amid reports that numerous parades in cities closer to Ukraine were canceled altogether for security concerns.

Mr. Putin, who ordered the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, nevertheless said Russia’s enemies were seeking the “disintegration and destruction of our country” and blamed the West for a “real war … unleashed against us again.”

Hours later, the U.S. announced a further $1.2 billion in security assistance for Ukraine, for everything from air-defense systems and 155mm artillery shells to commercial satellite imagery.

Meanwhile, as Ukraine’s final training rotations proceed, some analysts suggest that the spring offensive has already begun, in the form of rocket strikes and sabotage deep behind Russian lines.

Ukraine has in the past used U.S.-supplied HIMARS rockets to strike Russian supply lines and targets in Crimea, for example, which is home to a Russian naval base in Sevastopol and was occupied and annexed by Russia in 2014.

In recent weeks, oil storage facilities in Crimea have burned, causing dramatic fires, and two trains in Russia, not far from Ukraine, have been derailed – all attributed to Ukrainian drone strikes and sabotage. The Kremlin last week was also rocked by two overnight explosions, in what Russia said was a failed drone attack conducted by Ukraine on Russia’s seat of power. Ukraine denied any role.

Russia appears to have responded by aiming multiple waves of missiles and drones at targets across Ukrainian territory. It launched some 15 cruise missiles at the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, on Tuesday, for example – the sixth such attack on the capital in less than two weeks – though Ukrainian officials say all were shot down.

Last Friday, Russia-appointed authorities in the southeastern Ukraine area of Zaporizhzhia – the site of Europe’s largest nuclear power plant, which was seized by Russian troops in March 2022 – issued evacuation plans for 70,000 civilians. Previous such orders have presaged Russian retreats from occupied land. And this week came preliminary accounts, from both sides, of a substantial Russian setback around the long-contested Donbas city of Bakhmut.

At the training ground, patches affixed to uniforms speak to truisms discovered by Ukraine during this war. On one are the words, “Freedom is not free.” Another is a small American flag in camouflage colors Velcroed to the helmet of a soldier, who tests his assault rifle marksmanship from a trench position and gives the name Oleh.

Why does he wear that flag?

“Because the Americans are our friends,” he says.

Also friends are members of the Ukrainian volunteer group “Save Life,” which collects donations to buy military gear for front-line troops. On this day, two of the group’s representatives – decked out in military camouflage themselves, as they record a video of appreciation from soldiers for their donors – are on hand for the unboxing of two new Czech-made PKM light machine guns.

They are part of a consignment of 1,500 new guns promised by the volunteers to be spread across a number of Ukrainian units. Soldiers marvel as the guns are unwrapped in the sunlight, with parts glistening with factory oil. Grateful, they line up to take turns firing down range.

“How can you tell about taste, when you are really hungry?” asks a bearded staff sergeant with square-framed glasses, who gives the name Mykola. “If you don’t have enough weapons, you are happy with anything. If you have lots of weapons, you try to improve quality.

“This weapon will not last long in such an intensive war,” he says, nodding toward the new machine guns. “That’s why we are asking all the time for more and more weapons.”

Mykola says he was an entrepreneur who owned a computer company until he joined the military in 2014, when Russia seized Crimea and, with its local allied militia, the Donetsk and Luhansk regions from Ukraine.

“It’s been 10 years, so I probably learned something” about fighting the Russians, says Mykola. “You cannot underestimate your enemy. And the regular Russian soldiers, who want to survive, they will be ready. But their commanders, maybe not – they can send them to their deaths.”

What has he learned? “Only one thing: There are no rules that [the Russians] follow, so it’s useless to try to change or convince them. We need to fight, just to kill. But if they’re giving up, it’s much better for us,” he says.

That is a lesson learned also at a military medical stabilization center in the same region, closer to the front line, where a row of blood-stained stretchers outside is the only sign that this nondescript building has been converted into a key front-line transit point for wounded soldiers from the eastern front.

“You never know what kind of day you will have,” says a volunteer nurse and surgeon, who wears large disks in her earlobes in the Ukrainian national colors of yellow and blue and gives the name Valentyna. “It’s very quiet, or you get 100 people in a day.”

She notes 20 wounded soldiers arrived the day before, some requiring amputations, and 40 wounded the day before that.

“We also have to change positions often,” says Yuliia, a fellow volunteer nurse. That means packing up and moving the makeshift operating theaters and areas for treating trauma. “We just drink coffee and energy drinks, and keep on going.”

Those at this stabilization center say they are always prepared, and therefore plenty ready for the battles to come.

“We are over this … counteroffensive; everyone has been talking constantly about it since February,” says Valentyna. “Everyone wants this counteroffensive, but not all of them realize that we are not playing ‘Call of Duty,’ with an autosave function.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

How Carroll v. Trump revealed #MeToo era’s impact

The verdict against Donald Trump could go beyond implications for the former president, potentially signaling a greater willingness to believe women’s stories of assault.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A federal jury’s finding on Tuesday that former President Donald Trump is liable for sexually assaulting writer E. Jean Carroll in the 1990s, and defaming her since by calling her a liar, is a serious legal defeat for a man who once sat in the Oval Office and wants to do so again.

But in some ways, it may be more than that, say some experts. It could also be a marker for how the law and courts have evolved to make it less difficult – though perhaps still not easy – for women to tell their stories of assault and be believed.

“I think this verdict is a teachable moment for America. It demonstrates that jurors will believe survivors who bring sexual assault cases many years after the incident, because of the very real dynamics that deter them from coming forward,” says Barbara McQuade, a former U.S. attorney who is now a law professor.

The jury made its decision after only three hours of deliberation, ruling that Mr. Trump should pay around $5 million in damages to Ms. Carroll. Afterward Mr. Trump continued to insist that the assault never occurred and that he would press for the ruling to be overturned.

How Carroll v. Trump revealed #MeToo era’s impact

Asked about his “Access Hollywood” tape, the clip of him speaking flippantly about celebrities and sexual abuse of women that surfaced just prior to the 2016 election, former President Donald Trump explained his thinking.

Yes, on the tape he’d said that if you’re a “star” you can “do anything,” Mr. Trump acknowledged in his deposition last fall for writer E. Jean Carroll’s sexual assault and defamation lawsuit against him. Historically that’s been the case, he said.

“I guess that’s been largely true. ... Unfortunately or fortunately,” he said.

On Tuesday, a New York jury replied, in essence, “Not so fast. It’s not going to be true for this case, at least.”

The finding of the six men and three women of a federal jury on Tuesday that Mr. Trump is liable for sexually assaulting Ms. Carroll in the 1990s, and defaming her since by calling her a liar, is a serious legal defeat for a man who once sat in the Oval Office and wants to do so again.

But in some ways, it may be more than that, say some experts. It could also be a marker for how the law and courts have evolved in recent years to make it less difficult – though perhaps still not easy – for women to tell their stories of assault and be believed.

“I think this verdict is a teachable moment for America. It demonstrates that jurors will believe survivors who bring sexual assault cases many years after the incident, because of the very real dynamics that deter them from coming forward,” says Barbara McQuade, a former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan who is now a law professor at the University of Michigan.

A civil lawsuit

The Carroll lawsuit involves civil charges, unlike the historic criminal indictment of Mr. Trump last month by Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg on charges related to the payment of hush money to a porn star. Civil trials adjudicate disputes between people or organizations and don’t result in sentences of prison or parole. In the vast majority of cases, judgments against defendants result in money changing hands.

On Tuesday, after only three hours of deliberation, that is what the jury decided should happen. It ruled that Mr. Trump should pay around $5 million in damages to Ms. Carroll for sexually assaulting her in a dressing room at the Bergdorf Goodman department store sometime in the mid-1990s, and later using harsh language to call her a liar after she made her assault allegations public in a 2019 book.

The jury did not find that Mr. Trump raped Ms. Carroll, as she had charged.

After the verdict, Mr. Trump continued to insist that the assault had never occurred and that he would press for the ruling to be overturned.

“I have no idea who this woman, who made a false and totally fabricated accusation, is. Hopefully justice will be served on appeal!” Mr. Trump wrote Wednesday on Truth Social.

The former president has also continued to criticize federal District Judge Lewis Kaplan, calling him “completely biased” and “terrible.” Meanwhile, he has begun to raise money off the verdict. One fundraising letter emailed to supporters Wednesday morning said that the U.S. justice system has been hijacked by sinister political forces and Mr. Trump’s “freedom and justice did not matter to the Marxists who orchestrated this witch hunt in a city where the voter registration of the jury pool favors Democrats 7:1.”

A clash of two eras

The trial of Ms. Carroll’s accusations against Mr. Trump played out in the courtroom almost as a clash of two eras – the time before the #MeToo movement, and the time after.

As New York Times opinion columnist Michelle Goldberg put it, “The trial itself was a test of how much #MeToo has changed the culture.”

The New York state law under which Ms. Carroll was able to pursue damages for a decades-old incident was itself something of a #MeToo artifact. Under the Adult Survivors Act, which took effect late last year, victims of sexual abuse have until November 2023 to file civil complaints against their alleged abusers.

During the trial, Ms. Carroll’s lawyers took pains to explain to the jury why someone such as their client might have remained silent about abuse for years, afraid that they would not be believed and their allegations ridiculed. They talked about how victims of violence can remember some things vividly, and other things not at all – and how their reactions can vary in later years.

On the other hand, Mr. Trump’s lawyer, Joseph Tacopina, ran what might have been a textbook defense against sexual assault allegations in the 1990s, long before the pathbreaking rape prosecutions of Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein and comedian Bill Cosby.

Mr. Tacopina bored in on why Ms. Carroll had kept quiet so long, why she had not gone to the police at the time, and whether she thought rape was “sexy.”

He asked directly why she hadn’t screamed.

Ms. Carroll said she had tried to push Mr. Trump off her, stomped on his foot, hit him with her handbag, and tried to knee him.

“I was in too much of a panic to scream,” she testified. “I was fighting.”

In the end, the jury did not accept the old stereotype that an assault victim would surely scream as loudly as possible, behave in predictable ways, and run to law enforcement.

“The verdict ... demonstrates that the focus should not be on whether the survivor screamed or resisted, but on the misconduct of the assailant,” says Professor McQuade.

The 2024 presidential campaign

When Mr. Trump was indicted in early April by Mr. Bragg, his standing within the Republican Party strengthened. Voters who previously might have been leaning toward Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis or other possible GOP standard-bearers turned toward the former president, perhaps in solidarity against perceived Democratic overreach. Mr. Trump quickly built a solid nomination lead.

It’s difficult to predict whether that will happen again – or indeed, what will happen to Mr. Trump’s standing with the larger electorate. The Carroll verdict is the ending of a case, not a beginning. It involves ugly behavior. But it was a civil trial, a lawsuit – not a prosecution with the threat of prison at the end.

Mr. Trump survived the “Access Hollywood” tape once before, when it came out just prior to the 2016 vote. Some top Republicans thought his crude comments would doom him in the general election, and that he should drop out.

Journalist Robert Costa, then with The Washington Post, interviewed Mr. Trump the morning after the “Access” tape broke. On Wednesday he posted his memories of the encounter on Twitter. Mr. Trump was “flippant” and “short,” wrote Mr. Costa, who is now with CBS News.

When Mr. Costa asked about the issues raised by the tape, Mr. Trump kept talking about his core voters, focused on what he would say to them that day. He seemed bored by any discussion of moral or political consequences.

At the end of the interview Mr. Trump emphasized that he would never quit the race. “Forget that. That’s not my deal,” he said, according to Mr. Costa.

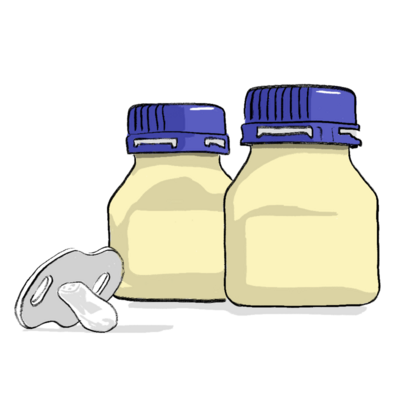

Saving African babies' lives by banking mothers’ milk

Breast milk can make an enormous difference in helping babies thrive. Now milk banks are blossoming in Africa, where they’re most needed.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Valentine Benjamin Contributor

Mothers’ breast milk can make the difference between life and death for babies around the world. But getting that milk from point A – mothers who have more than they need – to point B – babies whose mothers don’t produce enough – can be expensive and complicated.

The solution? Breast milk banks, which connect providers and consumers.

Globally, scientists estimate that breast milk, with its one-two punch of nutrients and immunity-boosting agents, could save the lives of more than 800,000 babies and young children every year. But the countries where milk banks are most needed, mainly in Africa, are the countries where the fewest such facilities exist.

Brazil is the world leader in this field, with a third of the world’s milk banks and child mortality rates that fell by 70% between 1990 and 2013.

In recent years, Brazil has taken its milk bank show on the road, helping to set up banks in Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking countries around the world – including in Africa. But many gaps remain.

Chinny Obanwanne is in the process of setting up Nigeria’s first milk bank, designed to help the most vulnerable: premature babies. “It gives them a higher chance of survival,” she says.

Saving African babies' lives by banking mothers’ milk

Inside a tidy mint-green room in an old industrial park in Johannesburg, a row of freezers hums and sighs. Behind them, a silver machine the size of a dishwasher sloshes hot water over three dozen bottles of milk. A sign on the wall signals the room’s raison d’être.

Breastmilk is nature’s health plan, it reads.

Around the world, milk banks like this one have sprung up as a solution to a public health issue that’s straightforward in itself but complicated to tackle. Breast milk can make the difference between life and death for many babies around the world, particularly those born prematurely. But getting that milk from point A – mothers who have more than they need – to point B – babies whose mothers don’t produce enough – can be expensive and complicated.

“It’s a huge undertaking,” says Emily Njuguna, a pediatrician and public health specialist who helped set up Kenya’s first human milk bank at Pumwani Maternity Hospital, a public hospital in Nairobi. Bureaucrats initially scratched their heads at her pitch. Expensive imported pasteurization machines broke down and then sat unused for months. Big bills for milk collection, medical testing, and storage gobbled up limited funds. “But the benefits have been immense,” she says.

Globally, scientists estimate that breast milk, with its one-two punch of nutrients and immunity-boosting agents, could save the lives of more than 800,000 babies and young children every year. In sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest infant mortality of any region in the world, its benefits could make a particularly large difference.

“It should make us all angry that in the countries around the world where we have the highest number of pre-term and low-weight newborns, there is also the lowest number of milk banks,” says Kiersten Israel-Ballard, a mother-and-child expert at the global health nonprofit PATH.

Brazil leads the way

Indeed, a quick glance at a map of the world’s milk banks reveals this inequality starkly. There are hundreds of milk banks scattered across Europe, but only seven African countries – South Africa, Angola, Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda, Cameroon, and Cape Verde – host even a single operational bank.

“I saw a huge gap,” says Chinny Obinwanne, a Nigerian doctor who is in the process of setting up her country’s first milk bank in Nigeria’s commercial capital, Lagos.

She was inspired to create a bank in part by a sobering statistic: In Nigeria, 1 out of every 8 children never reaches the age of 5. The country has the highest number of newborn deaths in Africa. Working as a lactation consultant, she thought that donated breast milk could make a dent in that problem by helping the most vulnerable – premature babies. It “gives them a higher chance of survival,” she says.

For African health care systems trying to set up milk banks, there’s one country that stands out as a global exemplar – Brazil.

Today, a full 30% of the world’s milk banks are located in Brazil, and they are considered a major factor in the country’s steep decline in child mortality, which plunged more than 70% between 1990 and 2013.

That story began in the mid-1980s, when a team of Brazilian officials led by a chemist named João Aprígio Guerra de Almeida set out to revamp a floundering milk bank system.

They started by eliminating payments in exchange for donated milk, which had encouraged many impoverished women to sell milk they should have been feeding to their own babies. Then they made donation and supply simple, setting up hundreds of collection points and even enlisting firefighters to ferry donations from women’s homes to hospitals.

When Mr. Almeida crunched the numbers, he found that medical-grade glass bottles to store milk were consuming more than 80% of his budget – so he replaced them with mayonnaise and coffee jars. He also swapped out imported pasteurization machines for locally made devices at a fraction of the cost.

And then he and his team went on a PR blitz. They enlisted popular soap opera actresses to explain the process and benefits of milk donation and persuaded the president to give a speech endorsing it. Flyers went out with the mail, and a toll-free hotline connected donors to couriers who collected milk straight from their homes.

“The thing that really stands out in Brazil’s model is they said, ‘this isn’t about creating milk banks – it’s about creating a bigger system that supports lactating moms,’” says Dr. Israel-Ballard. Indeed, the country’s milk banks are housed inside “breastfeeding promotion centers,” which also provide advice and training to mothers who are struggling with breastfeeding.

In recent years, Brazil has taken its milk bank show on the road, helping to set up banks in Portuguese- and Spanish-speaking countries around the world – including in Africa. But many gaps remain.

Literally a lifesaver

In Nigeria, Dr. Obinwanne watched in 2021 as a friend of a friend died in childbirth, leaving premature triplets behind. She scrambled to find breast milk for the babies among her clients and friends, but two of the newborns died before she could test and distribute the milk. “I felt like I had failed those babies,” she says.

So she began pouring her own money into setting up the infrastructure of a bank, buying freezers and equipment to pasteurize milk. Late last year, she began to collect breast milk, but since the milk bank isn’t linked to any hospitals or clinics, she has struggled to spread the word about it to those who most need it. Only one woman has used the service so far.

For milk banks in other African countries, getting early buy-in from local health care systems has been crucial. Each year, for instance, the South African Breastmilk Reserve (SABR) in Johannesburg distributes milk to about 4,000 babies in neonatal intensive care units at public and private hospitals across the country.

On a recent morning, as milk underwent pasteurization in the next room, the SABR’s director spoke on the phone to a donor about her impact.

“You’ve helped save 26 babies so far,” Stasha Jordan said.

“Wow, that’s amazing,” said René Rheeder, an information technology professional who gave birth to her second son late last year. “I know that for these babies, this is going to be their kick-start in life.”

Commentary

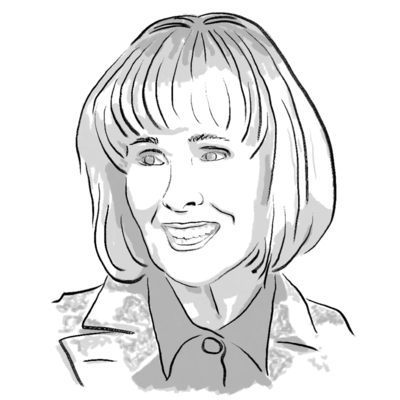

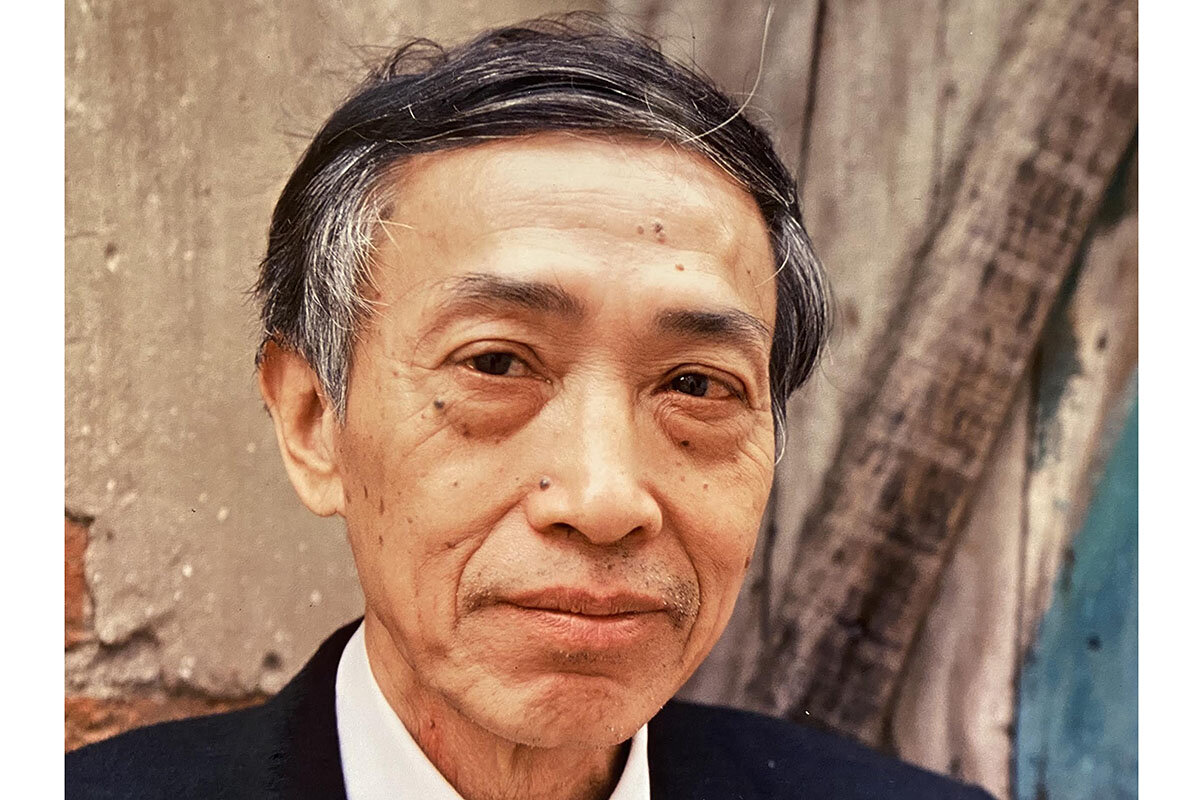

Bridging worlds with words: Poet, translator Duong Tuong

The determination and generosity of Vietnamese poet and translator Duong Tuong still resonate with this American photographer, bridging their different worlds.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Ellen Kaplowitz Contributor

It was 1998 in New York. I was planning my exhibit, “Layers Through the Mist, Vietnam Images,” held at what’s now known as the Penn Museum. Earlier that year, I had met translator and poet Duong Tuong in Hanoi, and now he was here, visiting the city with a group of his artist friends. I was invited to have dinner with him.

While eating, I told him about the exhibition. At that moment, he began to write one of his poems, “At the Vietnam Wall,” on a paper napkin. When I read those poignant words, I knew I wanted the poem to be included in my exhibit. He agreed.

Tuong had fought the French, joining the resistance and fighting against them for years. But their presence in the country had an ironic twist. Tuong taught himself French and English, and read books found in captured French outposts.

His translations introduced Vietnamese readers to Western literature of all types, from “Gone with the Wind” to works by Proust, Chekhov, Camus, and Tolstoy, among others.

But his words I treasure most are those he scrawled on that wrinkled napkin.

The poem remains relevant to our troubled times. The beauty of his words still inspires me: “because love is stronger than enmity.”

Bridging worlds with words: Poet, translator Duong Tuong

It was 1998 in New York. I was planning my exhibit, “Layers Through the Mist, Vietnam Images,” held at what’s now known as the Penn Museum. Earlier that year, I had met translator and poet Duong Tuong in Hanoi, the capital of Vietnam, and now he was here, visiting the city with a group of his artist friends. I was invited to have dinner with him.

While eating at Nha Trang on Baxter Street, I told him about the exhibition. At that moment, he began to write one of his poems, “At the Vietnam Wall,” on a paper napkin. When I read those poignant words, I knew I wanted the poem to be included in my exhibit. He agreed.

How I wish I had saved that napkin.

Initially, I photographed in Vietnam in 1993, uncertain how the people would react to me, an American. After all, I represented a former enemy. Their openness surprised me. During my many later trips to the country, I spent time photographing in rural areas. There, walking in the muddy soil of the rice fields and being invited into the homes of strangers to share tea, I came to understand the determination, discipline, and generosity of the Vietnamese people.

I first met Duong Tuong at his Hanoi home, which was also an art gallery managed by his daughter, Tran Phuong Mai. Opened in 1993, it was one of Hanoi’s first private art galleries, or, more accurately, a salon, where writers, artists, and intellectuals gathered for hours over tea or coffee, discussing life and critiquing each other’s work.

The building was a two-story, 1930s French villa with a courtyard. On the walls hung works by well-established masters along with pieces by the Gang of Five, five painters considered pioneers of Vietnamese contemporary art – Tuong supported their ideas and works. There were poetry readings and music performances as well. And drifting throughout were the smell of incense and the sound of vendors outside, shouting their offerings.

Foreign influences lingered, beyond the architecture. You could literally taste French colonial rule. I found great French bread everywhere, and I had the most delicious Napoleon pastry in a tiny Hanoi restaurant, where the owner wore a French beret, and a huge photo of himself with Catherine Deneuve, star of “Indochine,” hung on the wall.

Tuong had fought the French, joining the resistance and fighting against them for years. But their presence in the country had an ironic twist. Tuong taught himself French and English, and read books found in captured French outposts.

For decades after his army time ended in 1955, he wrote poetry, reported and edited for the Vietnam News Agency, and, to make ends meet, became a translator.

Tuong’s work introduced Vietnamese readers to Western literature of all types, from “Gone with the Wind” to works by Proust, Chekhov, Camus, and Tolstoy, among others. Given his background, this was an incredible feat.

When working on my book, “A World of Decent Dreams, Vietnam Images,” I realized how many Vietnamese people had read “Gone with the Wind.” Relating the novel to Vietnamese culture and values, one woman said that Rhett Butler would return to Scarlett because she cared so much about her family and their land. From this woman’s perspective, Rhett would have given a damn.

I admired not only Tuong’s intellect, kindness, and sensitivity, but also his determination, as he neared 90, to translate the 19th-century poet Nguyen Du’s narrative poem “The Tale of Kieu,” considered a masterpiece of Vietnamese literature. Tuong had thought of tackling it many times. Now he was ready. Barely able to see, he needed readers to assist him, but having learned much of it by heart, he also translated from memory. It was published as “Kieu: In Duong Tuong’s Version” in 2020, just a few years before his death earlier this year.

Poetry was always Tuong’s chosen vehicle to express himself. He constantly slept with words that inspired him and kept him up at night.

His words I treasure most are those he scrawled on that wrinkled napkin. Transferred to a large board, they hung next to my images where museum visitors could reflect on his thoughts.

At the Vietnam Wall

By Duong Tuong

because i never knew you

nor did you me

i come

because you left behind mother, father

and betrothed

and i wife and children

i come

because love is stronger than enmity

and can bridge oceans

i come

because you never return and i do

i come

Nearly 25 years later, that poem remains relevant to our troubled times. The beauty of these sleepless words still inspires me: “because love is stronger than enmity.”

For decades, photographer Ellen Kaplowitz has captured images around the world with a focus on Asia and Africa, recording people and places before what is unique to them is lost.

Difference-maker

Meet Peru’s unsung hero of the Pómac Forest

Reviving a forest is a community affair. But collective efforts often begin with a single person. In Peru’s Pómac Forest, that’s Carlos Alberto Llauce Baldera.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Carlos Alberto Llauce Baldera became a park ranger because he needed a paycheck. But in Peru’s Pómac Forest Historical Sanctuary, he found a lifelong career with purpose.

While Mr. Llauce credits others, he is an unsung hero of this dense tangle of algarrobo and mesquite.

This dry forest was once home to the pre-Inca Sicán culture. But for nearly eight years and ending with a violent eviction in 2009, hundreds of families were squatting illegally here. Lured by unscrupulous land speculators, the squatters clear-cut virgin equatorial trees, dug dozens of wells, built homes, and planted crops.

Nearly 15 years after helping guide police through the unfamiliar, dense forest terrain, Mr. Llauce remains dedicated to the patient rehabilitation and reforestation work that has resulted in a healthy reserve, alive with a cacophony of birds.

In recent years, Mr. Llauce and his Pómac ranger colleagues have spent a lot of time in the small settlements around the park to develop what is now a network of more than 280 volunteers – many of whom take part in park patrols.

“We’ve all come together to return lands that were so damaged to their beautiful natural state,” Mr. Llauce says. “This reserve will go on giving us all so much if we preserve and protect it.”

Meet Peru’s unsung hero of the Pómac Forest

Carlos Alberto Llauce Baldera holds the green seedpod of a young algarrobo tree as if displaying a piece of fine jewelry.

“These seedpods tell us the reforestation of this damaged area is a success,” says the seasoned park ranger at the Pómac Forest Historical Sanctuary in northern Peru’s Lambayeque region.

Not long ago this kind of discovery felt out of reach. For nearly eight years and ending with a violent eviction in 2009, hundreds of families were squatting illegally here on large swaths of the roughly 23-square-mile reserve.

According to locals, the park wasn’t well protected at the time, and families from distant Peruvian provinces arrived, lured by unscrupulous land speculators with promises of available parkland to purchase and settle. Their presence meant a trampling of the forest, where the squatters clear-cut virgin equatorial trees, dug dozens of wells, built homes, and planted crops.

Gesturing to a nearby, white-washed chapel sheltering the simple graves of two national police officers killed during the court-ordered evictions, Mr. Llauce adds, “Thanks to them our beautiful forest is coming back.”

While Mr. Llauce credits others, he is an unsung hero of the Pómac Forest, a dense tangle of algarrobo and mesquite that shelters more than 100 species of birds and numerous small mammals. This dry forest was once home to the pre-Inca Sicán culture, whose adobe pyramids still dot the landscape.

Nearly 15 years after helping guide police through the unfamiliar, dense forest terrain, Mr. Llauce remains dedicated to the patient rehabilitation and reforestation work that has resulted in a healthy reserve, alive with a cacophony of birds – and thriving algarrobos.

“We’ve all come together to return lands that were so damaged to their beautiful natural state,” Mr. Llauce says, referring to the surrounding communities and fellow guides, as he walks along a trail through thickets as impenetrable as a mangrove forest.

“Gives us life”

What initially started as a way for Mr. Llauce to take home a regular paycheck soon became employment with a purpose. He says he learned early on in his career, which began in 2000, that successfully protecting and preserving the Pómac Forest could never work if it remained important only to the reserve’s seven park guards – or to one-time visitors and the occasional biologist or archaeologist.

These days Mr. Llauce takes home stories of the work he’s doing – the birds that are thriving and the happy moments when he spots a favorite, like the Peruvian plantcutter and the huerequeque – to his two young sons. One of them, he notes proudly, says he wants to become a park guard one day, too.

“When I started here we had two big problems: the illegal cutting of wood, and chronic land invasions and illegal claim-staking,” he says.

“Back then the people who lived on the periphery of the park were a big part of those problems,” he adds. “But with a lot of community work to educate the neighbors, we can now say they are our partners. There’s a lot more understanding of the value of the park; we now work together to preserve its riches.”

In recent years, Mr. Llauce and his Pómac ranger colleagues have spent a lot of time in the small settlements around the park to develop what is now a network of more than 280 volunteers – many of whom take part in park patrols.

At the tiny settlement of Ojo de Toro Alto that sits just outside a park gate, Mr. Llauce stops at the home of Mauricio Villegas Cadenillas, a farmer who has served as a community volunteer since 2009.

The park ranger’s arrival sets off a whirl of activity: Mr. Villegas creates a circle of chairs for his visitors while his wife fetches a bottle of citrus water and a bowl of garden-grown mangoes.

“The park guards are very important parts of our lives here now. They are like brothers,” says Mr. Villegas, who takes a seat next to Mr. Llauce.

Mr. Villegas recalls that when he arrived with his family in 1994, “the forest was a marvel” for them. But gradually illegal woodcutting inside the park accelerated, sometimes carried out by neighbors, and then the squatters arrived.

By the time the squatters were evicted, he says, most of the park’s neighboring families were ready to take the counsel of park rangers like Mr. Llauce more seriously. “We talked a lot about protecting the woods, and most people around here have embraced that,” he says. “People understand that the forest purifies our air, and so it gives us life.”

In exchange for helping to protect the park, neighbors are allowed to undertake some activities in limited areas inside, including beekeeping, fruit-growing, animal grazing, and gathering algarrobo seed pods, says Mr. Llauce. When crushed, the seeds provide an energizing diet supplement that locals trace back to the laborers who built the Sicán pyramids.

“Critical” role

Mr. Llauce is one of 761 park guards across Peru whose job it is to protect and preserve the country’s natural riches for future generations. Indeed Peru, with its rainforests, high-mountain ecosystems, scorched deserts, long Pacific coastline, and unique environments like this dry forest, ranks among the world’s most biodiverse countries.

With the world’s ecosystems facing intense pressures, safeguarding that rich biodiversity has become increasingly important globally.

“This job is really about conservation of our country’s natural riches,” Mr. Llauce says – pausing when he hears the muffled buzz of a chainsaw somewhere across the park valley. He makes a note to check later for illegal woodcutting.

“It’s a risky job, not well paid, but one that is critical,” says Pablo Venegas, curator of amphibians and reptiles at Lima’s Center for Ornithology and Biodiversity.

He calls guards like Mr. Llauce “brave,” noting they are “out there confronting the illegal woodcutters, miners, and hunters, and the drug traffickers who use the parks to grow their products like coca or to transport them – and those bad actors are very often armed while the park guards are not.”

And he credits park guards with helping him in his professional pursuits, too. Over the past 16 years of scientific expeditions across Peru, Mr. Venegas has discovered dozens of new frog and lizard species.

“How many times have I shown guards a picture of the type of lizard I suspect is around there, and they’ll say, ‘yes we’ve seen that around this streambed or that part of the woods,’ and they’ll be right,” he says.

Pómac may not have the draw that Machu Picchu does, but Mr. Llauce says tourists and researchers still eagerly arrive, and are key to the local economy.

Surveying the park from a hillside overlook, Mr. Llauce points out numerous adobe pyramids poking out above the forest. These date back a millennium to the Sicán people.

“Those pyramids and the treasures many of them surely hold inside are our heritage, just as this beautiful forest is our heritage,” he says.

“This reserve will go on giving us all so much, if we preserve and protect it.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A calm beneath the fear of debt default

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The current political standoff in Washington over raising the U.S. debt ceiling is really a debate over the federal government’s spending priorities. Yet look deeper, and one can spot a consensus around the core tenet of self-governance.

Take, for example, the White House meeting Tuesday between President Joe Biden and senior lawmakers. Yes, it ended without a plan for Congress to raise the limit on how much the U.S. Treasury can borrow. But both sides outlined the contours of an eventual agreement, reinforcing a virtue of the nation’s founders that good can reinforce good.

“As leaders, our place in history depends on whether we call on our better angels,” House Speaker Kevin McCarthy recently told the Monitor. Renewing the norm of consensus, Washington’s leaders may be reaching toward a new stewardship of the common good.

A calm beneath the fear of debt default

The current political standoff in Washington over raising the U.S. debt ceiling is really a debate over the federal government’s spending priorities. Yet look deeper, and one can spot a consensus around the core tenet of self-governance.

Take, for example, the White House meeting Tuesday between President Joe Biden and senior lawmakers. Yes, it ended without a plan for Congress to raise the limit on how much the U.S. Treasury can borrow. But both sides outlined the contours of an eventual agreement, reinforcing a virtue of the nation’s founders that good can reinforce good.

“There are probably some places we can agree, some places we can compromise,” Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, a Democrat, said after the meeting. His counterpart, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, offered a similar assurance. “Let me first make this point: The United States is not going to default. It never has and it never will.”

The Treasury Department warns it will run out of funds to pay its bill on June 1 unless Congress lifts the debt limit or imposes big spending cuts. In April, House Republicans passed a bill tying the debt ceiling to spending cuts, some of which target the president’s policies. Mr. Biden rejects tying spending disputes to the government’s credit integrity.

Washington has been here before – 78 times, in fact, since 1960. More often than not, raising the debt limit hasn’t raised a ruckus. In stand-offs in 2011 and 2021, Mr. Biden and Mr. McConnell were instrumental in pulling back from the brink.

Both men are steeped in the Senate’s traditions of civility and deliberation. “I don’t always agree with him, but I do trust him implicitly,” Mr. McConnell said in speech on the Senate floor in 2016 paying tribute to Mr. Biden. “He doesn’t break his word. He doesn’t waste time telling me why I’m wrong. He gets down to brass tacks and keeps sight of the stakes.” Mr. Biden expressed his appreciation for the “very measured” approach that Mr. McConnell, in particular, brought to their discussions.

Having a debt ceiling, Kathleen Day, a business professor at Johns Hopkins, wrote recently, “helps remind everyone of the enormous burden our debt is, to the economy now and to future generations.” In recent periods of divided government, the debt ceiling has offered the party in opposition a way to seek leverage. This time, however, it may be having a different, elevating effect.

“As leaders, our place in history depends on whether we call on our better angels,” House Speaker Kevin McCarthy recently told the Monitor. Renewing the norm of consensus, Washington’s leaders may be reaching toward a new stewardship of the common good.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healing is meant to be

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Melissa Hayden

We don’t have to resign ourselves to misery or pain – nothing is beyond the healing reach of Christ.

Healing is meant to be

“It just wasn’t meant to be.” Have you ever heard yourself or another say that? Things didn’t turn out the way we thought they would, and we resign ourselves to assuming that’s the end of the story.

It’s, in essence, the answer a man in ancient Jerusalem gave when Jesus asked if he’d like to be healed of a physical problem he’d had for 38 years (see John 5:2-9). This man felt that his only pathway to health was to enter a pool thought to have healing water, and there were just too many obstacles preventing him from being able to get in at the right time.

Yet Jesus set all of those suppositions aside and immediately healed him. The man arose and went on his way, without ever having set foot into that water.

What had changed? Certainly none of the circumstances. But Jesus brought with him a different viewpoint – a spiritual outlook on health – that turned a seeming “it wasn’t meant to be” scenario into one of healing, right then.

What was it that Jesus knew that enabled the scene to shift so dramatically? A clue can be found in this statement from the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy: “Jesus beheld in Science the perfect man, who appeared to him where sinning mortal man appears to mortals. In this perfect man the Saviour saw God’s own likeness, and this correct view of man healed the sick” (pp. 476-477).

Because God, who created us, is divine Spirit, “God’s own likeness” and “mortal man” are mutually incompatible. As God’s likeness, we are spiritual and whole, not mortal and defective. Christ, Truth, enables us to discern and demonstrate this spiritual reality, this consistency of good, that Jesus proved – even when circumstances seem unyielding. Jesus’ healing works were not the result of happenstance or occasional divine interventions; rather, they gave evidence of repeatable, demonstrable, understandable spiritual law – which Christian Science elucidates.

We don’t need to accept that disease, failure, or any other type of negative circumstances are inevitable. Instead, what Christian Science makes plain is that health and well-being and harmony are truly inevitable – not in some afterlife, but right now. Rather than starting from the standpoint that a problem has valid power, we can pray to know that God, Spirit, alone is supreme. We can apply what we learn of this law to our own lives, overcoming resignation and instead realizing our innate health as sustained by Spirit, good.

This statement in the Bible shows the outcome of doing so: “Commit thy way unto the Lord; trust also in him; and he shall bring it to pass” (Psalms 37:5). That conscientious commitment to welcome Christ, to learn and follow God’s way, reveals enduring solutions, healing, and progress.

Years ago I had pain in my back and leg that seemed relentless. At times I thought I would simply have to learn to accommodate it indefinitely. But I instinctively rebelled against the idea that healing wasn’t meant to be and renewed my prayers all the more.

At one point I did a deep study of the Bible story mentioned earlier. As I gained a fuller glimpse of the Science behind what Jesus knew that freed that man – and countless others – from a seemingly unyielding problem, the condition simply faded away, never to return.

This poem by Mrs. Eddy conveys the tender wisdom of seeing healing as natural:

Father-Mother good, lovingly

Thee I seek, –

Patient, meek,

In the way Thou hast, –

Be it slow or fast,

Up to Thee.

(“Poems,” p. 69)

Viewfinder

Tribute of light

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come again tomorrow, when we report from the southern border on the end of the COVID-19 emergency – and a possible rush of asylum-seekers.