- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The writer who left Hollywood for ‘glimpses’ of grace

During Matt Williams’ career in television, he often heeded “a divine nudge.” The writer, who got his start at “The Cosby Show” and later co-created “Roseanne,” recalls lunching with a Canadian comedian. An inner voice told him, “Do this show with this man ... it will be a top 10 show.” The comic was Tim Allen. The ensuing sitcom was “Home Improvement.”

More recently, Mr. Williams felt a divine nudge to quit Hollywood. He’s launched a multimedia project titled “Glimpses,” a counterpoint to the darkness in the news. His new podcast and a forthcoming book focus on glimpses of God in everyday life.

“I’m talking about moments of grace, tenderness, unexpected compassion,” Mr. Williams explains during a Zoom call. “And yes, there’s horrible things happening, but in the midst of this darkness, there’s always a little flicker of light.”

He cites how the husband of an editor of his book flew with ex-servicemen to Poland, loaded a truck with medical equipment, and drove into Ukraine to teach civilians battlefield triage. Another example is Thomas Keown’s charity Many Hopes, which helps free children in Africa from injustices such as modern-day slavery.

Mr. Williams equates the process of creation to prayer. During a podcast interview with playwright Father Edward Beck, they discuss how stories can “inspire and heal because they connect us with the loving vitality of soul in each of us, and make it conscious to us.”

Mr. Williams says that the term “God” makes some fear that he’s going to start proselytizing. But his goal is to encourage his audience to tune out the algorithms of fear that fill our phones with gloomy headlines. One antidote is becoming attuned to the divine nudges to express kindness.

“It’s the human BitTorrent,” says Mr. Williams. “It’s passed from one person to another to another.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

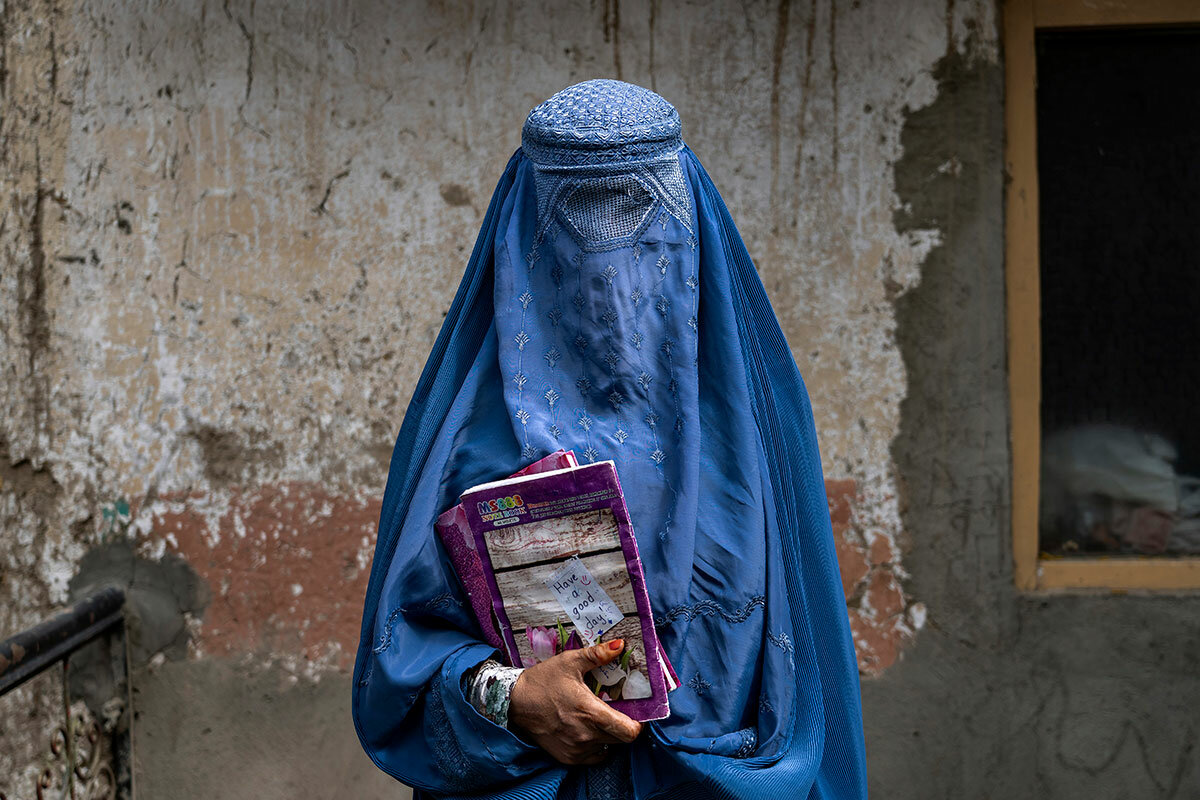

Secret schools defy Taliban to offer Afghan girls light and hope

In Afghanistan, an official ban on girls going to school has sparked defiance: Clandestine classes in private homes are keeping their learning, and their dreams, alive.

The first time she stepped into the secret school for girls, Maryam felt a rush of hope, as if rediscovering light after more than a year of darkness.

That was how long she had been confined to her home by the strict rules governing women’s behavior imposed by Afghanistan’s Taliban authorities. Now, she took her place on the red carpet among rows of other schoolgirls gathered in the drawing room of a private home in Kabul, transformed into an underground classroom.

Three volunteer teachers at the school offer clandestine classes to the 230 girls – forbidden to go to school by the ruling Taliban on religious grounds.

Now Maryam’s dreams are under threat again. For the past week, Taliban gunmen – armed with a new edict reinforcing a ban on education for girls over 15 – have been going from street to street in Kabul, hunting for underground girls’ schools.

Ms. F., the school’s 23-year-old director, is torn between the fear of being caught and severely punished by the Taliban, and the joy of learning she sees in her students’ eyes. She has shut her doors for two weeks, for safety’s sake.

But she hopes to reopen somehow. The secret school, she says, “is the most valuable thing I have done in my life.”

Secret schools defy Taliban to offer Afghan girls light and hope

The first time she stepped into the secret school for girls, Maryam felt a rush of hope, as if rediscovering light after more than a year of darkness.

That was how long she had been confined to her home by the strict rules governing women’s behavior imposed by Afghanistan’s Taliban authorities. Now, she took her place on the red carpet among rows of other schoolgirls gathered in the drawing room of a private home in Kabul, transformed into an underground classroom.

It was a revelation, recalls the slight 17-year-old with wide eyes and thick eyebrows and a rim of black hair visible beneath her headscarf, who dreams of computer programming. “Girls were studying, they had their books open, and the teacher was in front of the whiteboard.”

“It gave me the feeling that I had when we went to school in normal times,” says Maryam, whose last day of formal education was Aug. 15, 2021, the day Taliban insurgents ousted the American-backed government in Kabul. Like other Afghan women interviewed remotely for this article, she asked not to be fully named for fear of Taliban retribution.

“I again felt that motivation, and felt there was still hope,” she remembers. She was further encouraged by her teacher, Ms. F., her school’s 23-year-old director, who told the girls to look beyond the “dark situation,” not give up, and be hopeful for the future because “no situation will stay forever.”

Now, five months later, Maryam’s dreams are under threat again. For the past week, Taliban gunmen – armed with a new edict reinforcing a ban on education for girls over 15 – have been going from street to street in Kabul, hunting for underground girls’ schools.

Ms. F. says she has been torn between the fear of being caught and severely punished by the Taliban and the joy of learning she sees in her students’ eyes. She has shut her doors for two weeks, for safety’s sake.

It pains her, deeply. “In the hour they come here, the girls are different people and in a different world,” says Ms. F. “They have been imprisoned at home, so this is a chance for them to get out, take some fresh air, and get hope.”

Teaching English, math – and hope

When it functions, the school teaches English – to boost chances of foreign scholarships – as well as math, physics, and Quranic recitation. Classes are taught by three volunteers and are offered free of charge to the 230 girls in a staggered schedule so as to avoid attracting too much attention.

“Beside studies, I always get them [the girls] to tell me their pains, their feelings, and their problems, and I just listen to them and give them hope,” says Ms. F. Several times before, she says, she has been tempted to close the school “in order to save mine and the girls’ lives,” especially last September, when a suicide bomber killed 50 students taking a practice university exam at an educational center in Kabul.

But always the girls protested and changed her mind. “It was really hard for me to send the girls home,” she says. “You know it is the only light and hope for them, and for myself.

“How could I sit at home and do nothing?” adds Ms. F., whose eyes reveal an unmistakable look of determination in the portrait she displays on a messaging app. “Life with risk is better than death, or life with no reason.”

But this time she is not certain she will be able to reopen, because of the Taliban’s determination to deny girls education. That determination sometimes appears stronger than the Taliban’s desire to meet monumental national challenges, such as humanitarian needs the United Nations says “are at an all-time high,” a third year of droughtlike conditions, a second year of “crippling economic decline,” and the effects of 40 years of conflict.

“It is something that really surprises us. Why women? Why women’s education?” wonders Ms. F. The Taliban “don’t care that people are hungry. They don’t care that people have no jobs, no health care, [that] they are hopeless [and] in the worst physical and mental health condition.”

Ever more draconian restrictions

When the Taliban seized all of Afghanistan in mid-2021, their officials promised that schools and universities would stay open for girls and women, in contrast to the strict ban on female education that had prevailed when the Taliban first ruled the country, from the mid-1990s to 2001.

Instead, Afghan women have been subject to ever-tighter restrictions, which range from closing girls’ high schools and violently disrupting university exams, to barring women from public parks and forbidding them to work for U.N. agencies or international aid groups.

In a 62-page report last week called “The Taliban’s War on Women,” Amnesty International detailed how the Taliban’s “campaign of gender persecution” and “draconian restrictions” against women and girls, coupled with “use of imprisonment, enforced disappearance, torture, and other ill treatment,” could amount to crimes against humanity.

UN Women, a United Nations agency, last month described the “latest assault on women’s rights” – the ban on women working for the U.N. and nongovernmental organizations – as a “culmination of almost two years of edicts, decrees, and behaviors that have aimed to systematically erase Afghan women and girls from public life.”

For female Afghan students, the Taliban measures have stifled 20 years of expectations that arose during the American-led occupation, when Western donors contributed billions of dollars for development aid that included schools for Afghan girls and steps to dramatically open civil society to women.

The Taliban’s return has forced many Afghan women to curtail their ambitions. When the Monitor first interviewed Ms. F. last August, for example, the women’s rights advocate and educator, who once aspired to being her nation’s economy minister, had already repurposed her activism to create the underground girls’ school.

“I am a dreamer girl. I had many goals,” Ms. F. said then.

Last year “I was a bit hopeful, but now I am totally confused, unfocused, and tired,” says Ms. F. “I have a notebook where I am writing all my dreams, goals, and memories. Believe me, I can’t stop my tears when I cross them out because I can’t achieve them.”

Still, she says that “most days, I feel like [the school] is the most valuable thing I have done in my life. The girls tell me, ‘the energy we take from here is enough for the whole day.’”

Among those energized is Marzia, a 17-year-old who says her parents have tried to stop her from going to school because of the risks.

“It’s clear that the situation is very dangerous, but I try to hide my school books and don’t linger on the way, because my dream is so important for me,” says Marzia, who wants to go into politics.

“The happiest moment for me was when I went to this school,” says Marzia. “I met girls with high motivation, which caused me to get more motivated. It is like an incentive for me.”

She says she considers her presence in class a form of resistance: “Of course, the Taliban limit us, but we continue our dream in different ways.”

‘Nowhere to hide’: After murders in Amazon, local journalists at risk

The Amazon name may be ubiquitous, but the tragic murder of a reporter and environmentalist there last year highlights the invisibility of so many of the forest’s risks and realities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

It’s been a year since reporter Dom Phillips and Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira went missing while traveling the Itaguaí River in the Brazilian Amazon. Mr. Phillips was researching a book, to be titled “How To Save the Amazon.”

Ten days later, they were found murdered, and the two illegal fishers who confessed to the crime are currently in prison. This tragedy drew global attention and brought to light the dangers of the vast tropical forest that’s increasingly threatened by organized crime, land conflicts, and lack of law enforcement.

But perhaps nowhere have the ripples of this heartbreak been more acutely felt than among local journalists, who every day weigh their own safety against their responsibility to inform the public on what’s happening in their Amazon communities.

“If they do this with a reporter like Dom Phillips, an international reporter, without even thinking about it, imagine us who are from the region,” says Fabio Pontes, a freelance journalist from Acre’s capital city of Rio Branco. “We are much more exposed.”

In a sign of solidarity, colleagues and friends of Mr. Phillips are raising funds to publish his book. The work of Amazon defenders, and those willing to take the risk to report on it, lives on.

‘Nowhere to hide’: After murders in Amazon, local journalists at risk

The Amazon is touted as the “lungs of the planet” and is regularly mentioned in climate debates around the world. Yet for those living in and around the vast tropical forest, the international name recognition has masked a historic pattern of invisibility, where organized crime, land conflicts, and violence are left to flourish.

This contrast was brought to light one year ago today, when British journalist Dom Phillips and Indigenous expert Bruno Pereira went missing while traveling the Itaguaí River in the Brazilian Amazon. Mr. Phillips was researching a book that was to be titled “How To Save the Amazon.” Ten days later, they were found murdered.

The case shocked the world, raising the veil on the crises of organized crime and scarce law enforcement that dominate Amazonian border regions, especially where Brazil meets Colombia and Peru. And it ignited calls for stronger protections for anyone working to defend the Amazon.

But perhaps nowhere have the ripples of this tragedy been more acutely felt than among local journalists, who every day weigh their own safety against their responsibility to inform the public.

“The murders are the tip of the iceberg,” says Daniel Giovanaz, a project coordinator at Reporters Without Borders, who began monitoring threats to journalists in nine states of the Brazilian Amazon a month after the men were killed. Their findings include cases of direct threats of violence or death, abusive judicial processes meant to incriminate reporters, and cyberattacks or hacking.

“You have an environment that is extremely hostile to plurality, to independence, to freedom of expression at large,” Mr. Giovanaz says. When a journalist is silenced, whether by direct threat or self-censorship, “that violates the right of all society to have access to reliable information of public interest.”

“We know what’s going on”

Reporting in the Amazon has never been for the faint of heart. There are the inherent dangers of the jungle, from limited to no access to cell or internet services, to natural predators like anacondas and venomous spiders. Communities are often isolated, requiring travel along lonely rivers. Long-simmering land conflicts between farmers, miners, rubber tappers, and environmental and Indigenous activists mean outsiders are often viewed with skepticism. The growing presence of drug trafficking organizations has raised the stakes.

In a small city on the other side of the Javari Valley from where Mr. Phillips and Mr. Pereira were shot by illegal fishers, reporter Glédisson Albano counts out on his fingers the number of times he’s been threatened for doing his job.

There was the time he sprinted away from a tractor barreling toward him while reporting on waste dumping in a protected area. Just the other day, he was told he better be careful what he publishes, or he’ll get what is coming to him, he says.

Organized crime networks began operating in Cruzeiro do Sul in 2017, a time when he says he was reporting three or four deaths a day.

“It’s a small town; there’s nowhere to hide,” he says, looking out from his favorite hillside vista before beginning his workday. “If they want to threaten you, they do. They know where your house is, who your family is.”

When Mr. Albano heard the news about Mr. Phillips and Mr. Pereira last year, his heart sank. The two had been meeting with riverine and Indigenous communities to learn about their efforts to surveil the Javari Valley, Brazil’s second-largest Indigenous territory. Mr. Pereira was well known in the area for his efforts to stop illegal fishing and hunting. The men received death threats from illegal loggers, miners, and drug traffickers before they disappeared.

The Indigenous Missionary Council reported over 300 cases of land invasions, illegal exploitation of natural resources, and damage to property across 226 Indigenous territories in 2021. That’s nearly three times as many cases reported in 2018. Anyone perceived to pose a threat to those activities is at risk.

“We know what’s going on, but we can’t speak about it as we want to,” says Mr. Albano. He has watched colleagues leave journalism because of the danger.

“I feel obligated to cover, to publicize, to show what’s happening. That force takes us out of the house and makes us fight our fears,” he says.

Always an “eye on you”

Protections for journalists and environmental defenders already exist in Brazil, but human rights organizations and others are calling for them to be strengthened – and better enforced.

The two fishers who confessed to the crime are being held in prison awaiting trial, along with a third man who denies involvement. Two more men – suspected of involvement in the kind of illegal fishing Mr. Pereira was trying to halt – were also charged last week.

But locals say there needs to be an end to impunity in cases that don’t attract international attention, too. There were 44 journalists killed for their work in Brazil over the past three decades, and 62 more in neighboring Colombia and Peru, according to The Committee to Protect Journalists.

“If they do this with a reporter like Dom Phillips, an international reporter, without even thinking about it, imagine us who are from the region,” says Fabio Pontes, a freelance journalist from Acre’s capital city of Rio Branco. “We are much more exposed.”

Moving around in remote areas of the Amazon, whether by plane or riverboat, can be prohibitively expensive for freelance reporters. When he does travel, Mr. Pontes always goes accompanied by locals who know the areas. He no longer broaches questions of drug trafficking or organized crime.

“There is always someone who has their eye on you,” he says.

One outlet he works with is Amazônia Real, created in 2013 to re-imagine the role of reporting in the Amazon. Local and Indigenous people are central to their coverage, and the organization was one of the first independent outlets to report on the disappearance of Mr. Phillips and Mr. Pereira. They were tipped off by an Indigenous contact in the area.

“One of the big mistakes of journalism is to homogenize the Amazon region, as if it was one thing,” says Elaíze Farias, co-founder of Amazônia Real. “You have to pay extra close attention to the advice of locals.”

An even greater challenge for journalists who remain in the field, adds Mr. Pontes, is to “do journalism from the Amazon for those who are in the Amazon,” instead of audiences in São Paulo or New York. He says journalism will only thrive once populations here begin to value the forest and the local voices within it.

The Bruno and Dom Project

A few weeks before his death, Mr. Phillips stopped at an Ashaninka Indigenous village along the Amônia River. Dora Piyãko, a leader there, agreed to speak. She saw his reporting as important for her community’s struggle to protect their territory and culture.

The subsequent news of his and Mr. Pereira’s death was a shock. Local leaders came up with new safety protocols: Walkie-talkies became essential, community members now check in with those in the village frequently when monitoring the territory or traveling beyond its borders, and they try not to move around alone.

“We must be more careful now with whom we decide to speak, where we go,” says Ms. Piyãko. “We can’t always talk with the media because it could be risky.”

In a sign of solidarity – and hope – the work that Mr. Phillips and Mr. Pereira dedicated themselves to in the final years of their lives persists. More than 50 Brazilian and international journalists are continuing to investigate the destructive activities taking place in the Amazon as part of The Bruno and Dom Project. And a group of colleagues and friends of Mr. Phillips are raising funds to complete his reporting and publish his book. The work of Amazon defenders, and those willing to take the risk to report on it, lives on.

A path to guaranteed transfers for community college

What’s the best way to help community college students who want a four-year degree? In California, a proposal hopes to offer transfer students access to universities that have typically been out of reach.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When the University of California system proposed a universal guaranteed admissions program for community college students in March, it piqued the interest of those who seek entry into one of the most selective university systems in the United States.

If California legislators approve the guaranteed transfer program, for the first time it would include all nine UC campuses – including the Los Angeles, Berkeley, and San Diego campuses. It would also create a universal set of acceptance criteria for the more than 2 million California students who attend 116 community colleges in the state annually.

Students would not be guaranteed enrollment at the newly added schools, but they would be guaranteed to get into the UC system.

“Students get excited about a simpler path, and they are looking for California leaders to work out the challenges and make it happen,” says Jessie Ryan, with The Campaign for College Opportunity.

She says that the proposal needs to make clear how financial aid can be transferred from school to school, and that housing needs to be considered for acceptance, given that many students have work or family obligations nearer their homes.

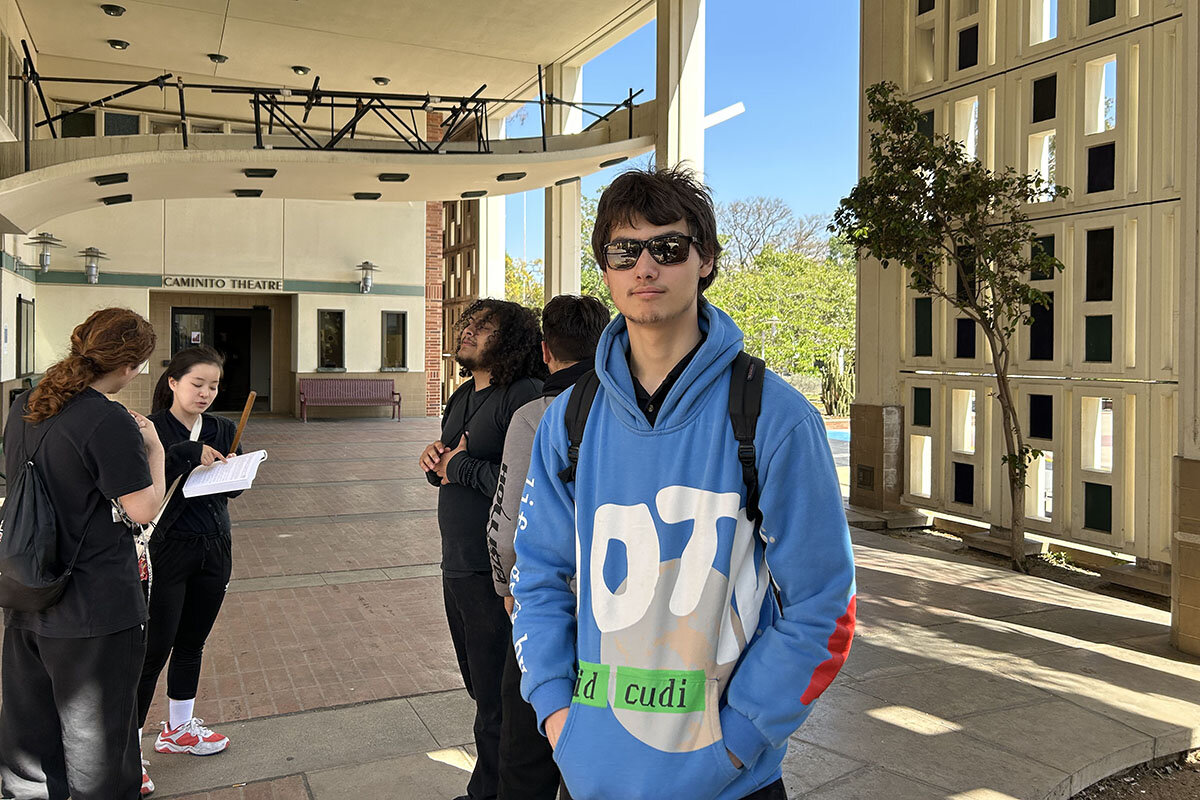

Scott Colonese, a first-year student at Los Angeles City College, has his eye on UCLA, a school he says offers a variety of subjects he can pursue.

“I think having a guaranteed path to get in is fantastic,” he says.

A path to guaranteed transfers for community college

When the University of California system proposed a universal guaranteed admissions program for community college students in March, it piqued the interest of those who seek entry into one of the most selective university systems in the country.

Scott Colonese is one of them. Multiple times a week he drives from his one bedroom apartment in Hollywood to Los Angeles City College with a 40-pound cello and hard case strapped to his right shoulder. A first-year student from Stockton, California, he made a pit stop at LACC before moving onto the place where he envisions himself.

“I want to go to UCLA,” the 18-year-old beams confidently, after attending classes on the LACC campus. “It’s the variety. I’d like to go into modeling. I want to go into some film stuff. I want to do music and just do art in general. So UCLA is a great place to be able to explore opportunities like that.”

The University of California, Los Angeles, and several other southern California branches of the university system rejected him straight out of high school, even though he had a 3.9 GPA, he says. “I was unlucky,” he adds, “but I think having a guaranteed path to get in is fantastic.”

If California legislators approve the guaranteed transfer program, for the first time it would include all nine campuses – adding three of the most selective schools: UCLA, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, San Diego. It would also create a universal set of acceptance criteria for the more than 2 million California students who attend 116 community colleges in the state annually.

“Students get excited about a simpler path, and they are looking for California leaders to work out the challenges and make it happen,” says Jessie Ryan, executive vice president for The Campaign for College Opportunity, a California nonprofit that advocates for access to affordable college for low-income and first generation students, and students of color.

For the first time, the most selective UC schools would be in the mix for community college transfer students. However, there’s no guarantee that someone will get into Berkeley or UCLA. What California would guarantee is admission to the UC system at either the Merced, Riverside, and Santa Cruz campuses.

A combined 70% of California community college students transfer to the UC system or the California State University system, with most going to CSU. Many students go straight from high school to community colleges, hoping that it will offer a path for them to get into the UC system, which has a more stringent set of admissions requirements.

Selective schools in the UC system have come under fire for not accepting more transfer students. The proposed transfer admissions initiative came after Gov. Gavin Newsom threatened to cut $20 million in state funding from UCLA if a transfer guarantee program was not created. However, the nonpartisan Legislative Analyst’s Office disagrees with the approach, noting that UCLA enrolls more transfer students “than any other UC campus.”

“The University of California is grateful to Governor Newsom for getting us started on a path to developing a more streamlined and easily understandable set of requirements to achieve guaranteed admission to the system,” Ryan King, a UC spokesperson, wrote in a statement to the Monitor. He notes that the idea is still at the proposal stage, but that “achieving a more accessible transfer pathway” is a “shared goal.”

The proposal would also create a uniform set of admittance criteria for the UC system for community college transfers. Overall, this would offer a clear path for students, including classes required and the GPA needed for admission – instead of students taking classes that they don’t need and trying specifically to meet individual requirements for each school.

But so far those specifics have not been released, Ms. Ryan says.

She says that the UC proposal also needs to make clear that whatever financial aid California students receive for one school in the system should be transferable to one of the other schools. And housing needs to be taken into consideration for acceptance, because many students have work or family obligations that keep them closer to UC schools near where they live, such as a school like UCLA.

Her organization has been advocating for the UC system to adopt the associate degree for transfer program, which the CSU system has. In fact, there is currently a state bill, AB-1749, which The Campaign for College Opportunity supports, that would include associate degree transfers for the UC system.

These types of steps are important, she says, because California needs to consider limiting brain drain. Already, attractive programs exist for students for guaranteed admission to 39 historically Black colleges and universities.

“We should be giving them that clear roadmap to transfer day one when they enter a community college,” she says.

George Limb wants to go to UCLA to be an actor. He says he’s been to Cal Poly Humboldt and Cal Maritime, but transferred to LACC with some general education courses that he thinks should make transferring into UCLA easier.

“The Cal States are easier. The UCs are hard,” he says. He’s doing what he can to stand out while still at a community college. He has a 3.3 GPA, but is working to increase that. And he has joined an acting troupe that he practices with at community college.

“If you put the work in you should be able to get into a good school,” he says.

But not everyone is interested in getting into a selective UC school. Erwin Meija has his mind on Cal State.

“I’ve spoken to counselors and they told me that UCs are more focused on research, and me personally, that’s not what I’m going to do,” says Mr. Meija, who started at LACC in fall 2022. He wants to be an accountant to help others, not to add to scholarship in the discipline.

He is interested in going to Cal State LA because it’s closer to his home in Culver City and it will be more affordable. And he feels like it will be easier to get into, since his GPA isn’t north of a 3.0.

“I’m just more concentrated on seeing if Cal States accepts me,” he says.

Guaranteed admissions could address declining enrollment across California’s institutions of higher ed, including community college transfer applicants. According to UC Institutional Research and Academic Planning, the total number of community college transfers – domestic and international – dropped university-wide from 38,879 in 2021 to 31,645 this year. One bright spot: As of 2021, nearly a third of UC undergraduates transfer from community college, and 88% of all transfer students graduate.

Transferring paid off for Yaseen Elhalafawy. He transferred to UCLA from Saddleback College, a community college in Mission Viejo, California, at the start of the current school year.

“It’s probably harder for freshmen to get in right out of high school, but the thing with community college is, if you’re doing it right it’s very easy to get it right. You just have to put in the work, but it’s not complicated,” Mr. Elhalafawy adds, standing in the hallway of Kerckhoff Hall, a Gothic structure on the UCLA campus that evokes Hogwarts. The student newspaper and student government office is here, and transfer students have their own space where they congregate.

Mr. Elhalawafy says GPA matters, but so do things like extracurricular activities.

“I played tennis. I was pro for a while,” he says. The pandemic shut that down, and he went back home to Orange County to work with a community organization teaching kids the fundamentals of the sport. Because he had a high GPA and an interesting story, he aimed for the stars in terms of the schools that he applied to, even the Ivy League.

“This is a good institution,” he says, smiling. “It’s the No. 1 public institution in the country.”

He is in an honors program and wants to work in local government and possibly be a city council member one day. Everything is possible, he says.

“I know this is a dream school for a lot of people,” he says. “There’s probably a lot of people where [UCLA] just had to make a decision and say no. I know people who got into Berkeley that didn’t get into here, so there’s always more opportunities to transfer in from another school.”

Points of Progress

Boosting jobs: Coding camps and streamlining for startups

In our Progress roundup, governments and private companies are removing barriers to better jobs and innovation, from Argentina to Benin. And, in science news, we highlight a discovery for the future of electricity.

-

Angela Wang Staff writer

Boosting jobs: Coding camps and streamlining for startups

1. French Polynesia

Partula snails are making a comeback, after the largest-ever release of any “extinct in the wild” species.

Partulids eat decaying plants and fungi, making them an important part of the forest ecosystem. As separate species are endemic to single islands, their shells have played a significant role in local cultures.

The snails were nearly wiped out by the rosy wolf snail, which was introduced to the islands to eliminate the invasive African giant land snail. The few surviving partulids were rescued in the early 1990s, when zoos in Europe and the United States collaborated to breed 11 different species of the gastropods.

Scientists began reintroducing the snails nine years ago to predator-proof reserves on the islands of Moorea and Tahiti. Since then, 21,000 snails have been delivered to the islands – 5,000 of them this year.

Paul Pearce-Kelly, who coordinates the conservation program, said the snails are “the Darwin’s finches of the snail world, having been researched for more than a century due to their isolated habitat providing the perfect conditions to study evolution. This collaborative conservation initiative ... shows the conservation power of zoos to reverse biodiversity loss.”

Sources: The Guardian, IUCN Red List, Zoological Society of London

2. Canada

Engineers designed a powerful nanogenerator that harnesses vibration, using the same phenomenon that lights a gas stove and keeps a quartz watch accurate. The thin, 2.5-square-centimeter example of energy harvesting could be used to self-power electronics like internet-connected thermostats.

At the Universities of Waterloo and Toronto, researchers made a compound that works based on the piezoelectric effect, in which electricity is produced by mechanical pressure on a material. That pressure moves atoms around in the crystal structure to produce an electric charge.

Asif Khan, a co-author of the study, says their metal-halide compound, EDABCO copper chloride, “can harvest tiny mechanical vibrations in any dynamic circumstances, from human motion to automotive vehicles.” In an example of the team’s vision, aircraft vibrations could power the craft’s sensory monitoring systems, without using nonrenewable energy or lead-based piezoelectric materials.

Sources: Nature Communications, University of Waterloo

3. Argentina

Young, low-income Argentines are finding well-paying jobs through coding boot camps. The free coding and information technology classes are government-initiated and subsidized by Argentina’s tech industry, which struggles to find skilled workers for booming tech jobs.

Argentina Programa 4.0 launched in November, offering free two to three months’ training in coding languages and other digital skills, plus job placement in software companies. Access to high-quality computers and the internet remain barriers, so many of the courses offer free equipment as well. So far, 210,000 students have taken courses, according to a spokesperson for the initiative.

At the end of 2022, Argentina’s unemployment rate stood at 6.3%, yet as many as 40% of Argentines live below the poverty line. Entry-level tech jobs generally pay well above minimum wage.

Puerta 18 is a nonprofit in Buenos Aires that offers free courses on 3D printing, programming, and graphic design. “Right off the bat, they often become the highest earner in the family,” says director Federico Waisbaum.

Sources: Context, National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Argentina

4. Benin

Young people in Benin are a growing share of booming entrepreneurship. More than 27,000 new businesses were founded in 2019, 27% of which were started by young adults ages 18-30. Three years later, the number of new businesses was twice as many, and 41% of those were founded by young people. A third were started by women.

Officials say the increase is driven by a new e-government platform called MonEntreprise.bj, developed by the U.N. Conference for Trade and Development and supported by the Netherlands, that streamlines some normally bureaucratic processes, making it easy to launch and support digital businesses. The software is also in use in 10 other developing countries.

Caludia Togbe used it to create Origine Terre, a cosmetics business, in 2020. After registering on the digital platform she expanded her product line and was able to sell internationally. “I couldn’t wait for someone to hire me, so I decided to create my own job, and hire myself,” she said. “I always knew I wanted to be my own boss.”

Source: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

5. Pakistan

After devastating floods, southern Pakistan is rebuilding with low-cost, water-resistant housing developed by the country’s first female architect. Yasmeen Lari co-founded the Heritage Foundation of Pakistan in 1980 to pioneer design for sustainable shelters and housing that could be built by the people who need them. Although some express concern that brick and cement are more permanent, Ms. Lari’s lime, mud, and bamboo homes are better than traditional mud huts at withstanding extreme weather events.

The foundation has already helped build 4,500 houses for survivors of the floods, which destroyed more than 2 million homes. Structures take about a week to build and cost less than $100. Ms. Lari was recognized with the Royal Institute of British Architects’ 2023 medal for a lifetime of socially conscious work that emphasizes self-reliance.

“We need a paradigm shift from charity to empowerment, from dependence to self-reliance, from women being suppressed to placing them in the lead,” writes Ms. Lari. “Every one of the vulnerable should learn to build safe structures so that they are not displaced and they are able to fend for themselves [when a disaster strikes].”

Sources: Context, CNN, The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

Essay

A hot, tomato-and-cheese solution to anguish

Solace can be offered, but it must be embraced. Sometimes, comfort is best served atop something hot and cheesy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Robert Klose Contributor

Pizza! It garners almost universal enthusiasm as a respite from Friday night cooking, an affordable meal on the fly, or a way to grease the skids of a dreaded business meeting. But I was unaware of its therapeutic value until I had kids.

I adopted my older son, Alyosha, in Russia when he was 7. I was a single parent, and we had a good start. But when he was 8, something – I don’t recall what – didn’t go his way, and he announced, “I go back Russia.”

I watched as he walked out the door. I caught up and walked alongside him down the street.

“It’s far,” I told him.

Staring straight ahead, Alyosha replied, “I don’t care. I walk.”

I added, “There’s an ocean between here and Russia.”

Alyosha didn’t miss a beat. His response: “I take boat.”

I took aim at his heart. “I’ll miss you,” I said.

Alyosha plodded on but replied, “I miss you too.”

Finally, after a long stretch, I suggested, “How about pizza?”

His response: “OK.”

And that was that. He never made it to Russia.

To appropriate a well-worked adage, a slice of pizza is sometimes worth a thousand words of consolation.

A hot, tomato-and-cheese solution to anguish

Pizza!

There have been many paeans to a dish that garners almost universal enthusiasm, whether it’s as a respite from Friday night cooking, an affordable meal to eat on the fly, or a ready way to grease the skids of a dreaded business meeting.

For me, I was unaware of pizza’s therapeutic value until I had kids.

When my boys were still growing, most situations were easily addressed: If you don’t pick up your room, you can’t go out to play. But there were also moments when the solution wasn’t evident to me, and as a single parent, there was no other adult in the house to consult.

I adopted my older son, Alyosha, in Russia when he was 7. We had a good start. But one day, when he was 8, something – I have long since forgotten what – didn’t go his way. He was still getting English under his belt, and, having not prevailed in the matter, he announced, “I go back Russia.”

I looked on as he walked out the door. Then I caught up and walked alongside him as he made his way down the street.

“It’s far,” I told him.

Staring straight ahead, he replied, “I don’t care. I walk.”

We continued on, and I added, “There’s an ocean between here and Russia.”

Alyosha didn’t miss a beat. His response: “I take boat.”

I finally aimed for the heart: “I’ll miss you.”

Alyosha plodded on but replied, “I miss you too.”

Finally, after a long stretch, I suggested, “How about pizza?”

His response: “OK.”

And that was that. He never made it to Russia.

When my second son came along, adopted from a Ukrainian orphanage at the age of 5, the waters of his life with me were roiled in his sixth year, when he became enamored with a 5-year-old girl in a neighbor’s family. One cold, dark evening, he took to his heels, intent on visiting Diana against my wishes. I had quite a time locating him, but I eventually found him standing on a traffic island, tears coursing down his cheeks because he couldn’t figure out how to navigate the crossing. I threw a jacket around him and gathered him into my arms.

“How about pizza?” He wiped his tears on his sleeve and sniffed, “OK.”

A short while later the ardor of his love was being attenuated by the sweet taste of pepperoni nestled within a double-cheese crust.

Both of these adventures suggested the enduring value of what I call “the pizza cure.” Its beauty lies in its simplicity. I have observed that, confronted with a variety of exotic toppings – I recently noted kale, chard, and pineapple pizza with caramelized onions – most people will still choose a slice of plain cheese pizza. It is time-tested, familiar, unpretentious. And it has proved to be a balm for an assortment of maladies, beyond rescuing children from the perils of a trek to Russia or the devastation of unrequited love. By way of example, one of my students recently confided a minor personal crisis to me. Nothing I said could pull him out of his slough of despondency, and so I acted. I took him to a local pizza joint and watched as he tucked into a magazine-size slice of double cheese, double crust. Moments later the clouds had parted and the light of alleviation shone through. The world once again seemed manageable.

To appropriate a well-worked adage, a slice of pizza is sometimes worth a thousand words of consolation.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The liberation of Iran’s women athletes

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Women in Iran were a bit stunned last month when, for the first time, national television allowed a live broadcast of an Iranian women’s sports team playing in an international tournament. Inside Iran, women are rarely, if ever, allowed into stadiums to watch men play. Almost as stunning was that the televised sport – ice hockey – did not exist for women until a few years ago in an arid country where powerful clerics have long discouraged women from participating in athletics.

Iran’s female hockey team, created only in 2020, came in a close second during a matchup of Asian teams in Thailand in April and May. “Our achievement can help all of Iran’s women to know that there is nothing that can stop them,” the team’s captain, Azam Sanaei, told Al Jazeera.

Excelling in a sport has long been a way for suppressed people to claim freedom and equality for themselves. For women in Iran, who have been at the forefront of major protests in Iran during recent decades – especially in 2022 to oppose mandatory head covering – sports have become an alternative and affirming route to social liberation.

The liberation of Iran’s women athletes

Women in Iran were a bit stunned last month when, for the first time, national television allowed a live broadcast of an Iranian women’s sports team playing in an international tournament. Inside Iran, women are rarely, if ever, allowed into stadiums to watch men play. Almost as stunning was that the televised sport – ice hockey – did not exist for women until a few years ago in an arid country where powerful clerics have long discouraged women from participating in athletics.

“The perfection of a woman lies in motherhood,” declared one Muslim cleric in 2014.

Iran’s female hockey team, created only in 2020, came in a close second during a matchup of Asian teams in Thailand in April and May. “Our achievement can help all of Iran’s women to know that there is nothing that can stop them,” the team’s captain, Azam Sanaei, told Al Jazeera.

Excelling in a sport has long been a way for suppressed people to claim freedom and equality for themselves. For women in Iran, who have been at the forefront of major protests in Iran over recent decades – especially in 2022 to oppose mandatory head covering – sports have become an alternative and affirming route to social liberation.

“Like a mighty river blocked by giant boulders, the movement [for women’s emancipation in Iran] continuously finds a new path, sometimes in entirely unanticipated ways,” wrote Janet Afary and Kevin Anderson, two scholars at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in a recent Dissent magazine article.

Sports for Iranian women largely ended in 1979 when the Islamic Republic was founded. In recent years, the gradual revival of women's sports has been supported by regime reformers who see the advantage of stoking national pride when Iranian athletes win international games. In 2018, when Hassan Rouhani was president and seen as a moderate leader, he wondered aloud why women’s sports should not be broadcast on television. “Why we cannot show the events, especially when they compete bravely with world-famous teams and win great victories?” he asked in a question probably directed at the dominant clerical leadership.

The women who have pursued excellence in ice hockey – helping bring public interest in watching the team on live TV – have answered his question.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

When hearts catch fire

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Liz Butterfield Wallingford

Opening our hearts to the light of divine Love has a transformative impact, sparking empowerment and healing in our lives.

When hearts catch fire

In “Catching Fire,” the second book (and film adaptation) in the popular young adult series “The Hunger Games,” there’s a scene where the main character, Katniss, wears a dress that becomes engulfed in flames as she twirls. (It’s engineered in such a way as to not harm anybody.) It’s a striking moment that speaks to a variety of themes, including hope and strength in the face of seriously challenging circumstances.

Needless to say, this isn’t the kind of apparel we’d find in our own closets. But we can experience the dynamic, empowering sensation of hearts catching fire.

For me, this has come most meaningfully through my study and practice of Christian Science. Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered Christian Science, shared her discovery in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” There’s a vivid phrase in this book that describes this Science as “aflame with divine Love” (p. 367).

Divine Love is another name for God, the infinite source of all that’s good and true. This supremely powerful, entirely pure, and unreservedly tender Love is at the very heart of Christian Science. In fact, this Science is the law of divine Love that Christ Jesus’ ministry revealed and proved.

Christian Science teaches the nature of God as not only Love but also constant Principle, intelligent Mind, unvarying Spirit, eternal Life, reliable Truth, harmonious Soul. It conveys the true nature of each of us as God’s spiritual, loved child – reflecting the love, integrity, and beauty of our Maker.

The spiritual truths Christian Science puts forth have sparked hope in countless lives and situations. And because that spark stems from infinite, all-powerful Love, it’s more than blind faith or optimism. It has serious substance – it rejuvenates, reforms, and cures.

Indeed, the more we soak up this divine Science of being and strive to make it our own, the more we come to realize that it’s more than theological points on a page. We feel the figurative flames of divine Love warming our hearts, revealing our true nature as divine Love’s self-expression – fueling compassion, joy, understanding, and healing.

In turn, anger, illness, inharmony, fear – whatever is illegitimate under the law of Love and therefore an error about our real identity – is burned off. I’ve experienced this firsthand, as have so many others across the globe.

The author of Revelation writes, “I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire” (Revelation 10:1). Science and Health includes an explanation of this passage that says in part, “To mortal sense Science seems at first obscure, abstract, and dark; but a bright promise crowns its brow. When understood, it is Truth’s prism and praise. When you look it fairly in the face, you can heal by its means, and it has for you a light above the sun, for God ‘is the light thereof.’ Its feet are pillars of fire, foundations of Truth and Love. It brings the baptism of the Holy Ghost, whose flames of Truth were prophetically described by John the Baptist as consuming error” (p. 558).

The “bright promise” of divine Science is timeless and universal. Each of us can strive to base our lives on the strong foundation of unchanging, infinite Truth and Love. We can let the incomparably bright light of God, good, guide our path and kindle our innate receptivity to the joy-bringing, harmonizing, and healing Christ, Truth.

Talk about a heart catching fire!

Viewfinder

Pride Month gathering

A look ahead

You’ve reached the end of our package of stories today. Tomorrow’s lineup includes a look at an unprecedented debate within the U.S. about whether rules about children’s work should be relaxed.