- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How religious liberty became the Roberts court’s North Star

- What court’s rejection of student loan relief means

- Why Russia crisis requires US vigilance

- Reparations in California: What can lawmakers achieve?

- Our writers’ takeaways from digging into reparations

- In search of summer beach reads? Read on.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

‘When will talk of reparations be finished?’

In reporting and editing on the Monitor’s ongoing reparations project, I’ve been reminded repeatedly by sources that reparations are a process – institutional as well as personal. They are not a big-fix payoff with an endpoint. Most often, they are not financial at all, but an acknowledgment of, atonement for, and education about the cascade of damage sent rolling down the centuries by slavery.

As Monitor reporter Ali Martin reports in today’s Daily, California’s Reparations Task Force sent the legislature its recommendations yesterday, but that’s just the beginning; the state has to figure out what it can actually do.

“When will this be finished?” is a frequent question reparations advocates field from white people.

“There is no endpoint,” answers Debby Irving, who wrote the book “Waking Up White: And Finding Myself in the Story of Race.” The undergirding of reparations “isn’t linear. It’s cyclical. ... Reparations is not a one-and-done. Who knows when there will be sustainable balance? But that’s going to take years and years.”

When she first started to probe her own feelings about race, wrote Ms. Irving, “I didn’t think I had a race, so I never thought to look within myself for answers. ... I thought white was the raceless race – just plain, normal, the one against which all others were measured.”

She points to an “inexplicable tension” many white people admit to when considering race, a feeling of “something’s not right.”

Addressing that feeling can often be the first order of business in the reparations process.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How religious liberty became the Roberts court’s North Star

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court added two more rulings to its growing list of pro-religion decisions, which continue to profoundly reshape the nation’s religious jurisprudence.

During the tenure of Chief Justice John Roberts, the United States’ high court has in many ways redefined the meaning of religious freedom in America. The Supreme Court has become not only a robust defender of those with sincerely-held religious beliefs. It has also become a court not shy about upending long-standing legal traditions and overturning previous decisions about the meaning of the First Amendment’s religion and speech clauses.

On Thursday, a unanimous Supreme Court overturned more than 45 years of precedent when it ruled in favor of an evangelical Christian postal worker who sued, saying the U.S. Postal Service violated the Civil Rights Act when supervisors would not accommodate his request to have Sundays off.

On Friday, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of a Colorado website designer who argued that creating a wedding website for same-sex couples would violate her First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

The courts led by Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren Burger issued pro-religion decisions in roughly half of cases. It was 58% in the court presided over by William Rehnquist. The Roberts court, however, has caused a “transformation of constitutional protections for religion,” scholars say, issuing pro-religion decisions in over 85% of cases.

“The Roberts Court is indeed a historic anomaly in its religious liberty decision-making,” says Joanna Wuest at Mount Holyoke College.

How religious liberty became the Roberts court’s North Star

During the oral arguments surrounding the religious liberty questions in Groff v. DeJoy late last year, U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts told one of the lawyers that some previous federal cases about religion in American life may no longer be useful as a guide for deciding those in the future.

“Well, the law has developed in this area,” Chief Justice Roberts said, giving a short list of some of the momentous religious freedom rulings issued by the court he has led for almost 20 years. “You will, of course, have to take into account our religious jurisprudence as it exists, right?”

This week, the U.S. Supreme Court added two more rulings to its growing and unprecedented list of pro-religion decisions, which continue to profoundly reshape the nation’s evolving history of religious jurisprudence.

On Thursday, a unanimous Supreme Court overturned over 45 years of precedent when it ruled in favor of an evangelical Christian postal worker who sued the U.S. Postal Service, saying it violated the Civil Rights Act when supervisors would not consistently accommodate his request to have Sundays off, with Sunday being an important day of worship in his life.

Then on Friday, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of a Colorado website designer who argued that creating a wedding website for same-sex couples would violate her First Amendment right to freedom of speech.

During the nearly two-decade tenure of Chief Justice John Roberts, the nation’s high court has in many ways redefined the meaning of religious freedom in America. The Supreme Court has become not only a robust defender of those with sincerely-held religious beliefs. It has also become a court not shy about upending long-standing legal traditions and overturning previous decisions about the meaning of the First Amendment’s religion and speech clauses.

The courts led by Chief Justices Earl Warren and Warren Burger issued pro-religion decisions in roughly half of their cases. It was 58% in the court presided over by William Rehnquist. The Roberts court, however, has caused a “transformation of constitutional protections for religion,” scholars say, issuing pro-religion decisions in over 85% of its cases.

“The Roberts Court is indeed a historic anomaly in its religious liberty decision-making,” says Joanna Wuest, professor of politics at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

In the unanimous Groff decision on Thursday, the justices agreed that the religious rights of employees needed to be expanded. The Civil Rights Act forbids employers from discriminating against workers because of their religious practices, unless they can demonstrate that such practices cannot be accommodated at work without “undue hardship.”

In 1977, the Supreme Court defined “undue hardship” as anything more than a trivial or minimal cost to the employer, a standard known as “de minimis” that made it more difficult for a worker to obtain accommodations. Writing for the unanimous court, Justice Samuel Alito said that definition was “a mistake.” Now, an employer must prove “substantial increased costs” before denying a religious accommodation.

But in the case concerning the free speech rights of the Colorado website designer, in 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis, the Supreme Court addressed one of the most divisive cultural questions in the country: May those with sincere religious beliefs against same-sex marriage be able to refuse to provide service when it comes to same-sex weddings?

It’s a question that has rankled the country even before the Supreme Court declared same-sex marriage a constitutional right eight years ago in Obergefell v. Hodges. Since then, religious conservatives have been on a legal quest to carve out certain exceptions to laws that protect LGBTQ+ people.

As a legal matter, their claims involve only refusing service for the ritual aspects of same-sex nuptials, as a matter of religious belief and conscience, but not LGBTQ+ people in general, proponents say.

Religious conservatives have based many of their legal arguments on both the provisions of the First Amendment that guarantee the free exercise of religion and freedom of speech. In 2018, the Roberts court declined to issue an opinion on these claims, even though it ruled in favor of a Colorado baker who also refused to provide service for same-sex weddings, saying Colorado’s Civil Rights Commission was biased against religion in its ruling against the baker.

In Friday’s ruling in 303 Creative, however, Justice Neil Gorsuch was clear: “The First Amendment prohibits Colorado from forcing a website designer to create expressive designs speaking messages with which the designer disagrees. ... Colorado seeks to force an individual to speak in ways that align with its views but defy her conscience about a matter of major significance.”

“Freedom not to speak”

As a legal matter, this was a ruling about the scope of free speech, but not the free exercise of religion, per se.

“Free speech includes the freedom not to speak,” says Sherif Girgis, professor of law at Notre Dame Law School in Indiana and a former Supreme Court law clerk for Justice Alito. “The government can’t force you to say, do, or make something that carries a message you reject. [This case] will allow refusals to make expressive products based on the messages they convey – not based on the identity of the customers.”

“It’s a right to be discriminating about messages, not a license to discriminate against customers,” Professor Girgis says. “If you’d make an item carrying a given message for straight people, you have no free speech right to refuse that item to gay people. But if you’d refuse to facilitate a certain message no matter who asked for it, the First Amendment protects your choice.”

In his opinion, Justice Gorsuch wrote, “The First Amendment envisions the United States as a rich and complex place where all persons are free to think and speak as they wish, not as the government demands.”

Opponents of the decision, however, say this understanding of free speech not only upends long-standing nondiscrimination principles when it comes to public accommodations – the idea that any public business or service must serve everyone, regardless of identity. It also only bolsters the kind of discrimination that LGBTQ+ people have always had to endure.

“There’s no basis on which people should be excluding each other or denying services or refusing jobs to people when we’re in the public realm,” says Jennifer Pizer, chief legal officer for Lambda Legal in Los Angeles. “That is supposed to be there for everybody – the public marketplace, public services, the entire public realm.

“So in a way, we see this movement to refuse service as very problematic and dangerous, not just for LGBTQ people, who are the particular target of much of their advocacy, but for society as a whole,” she continues.

America’s changing landscape

Taking account of the broader landscape, however, William Eskridge, professor of jurisprudence at Yale Law School and one of the nation’s leading scholars on the legal aspects of same-sex marriage, says that today’s decision will not necessarily thwart the many gains of LGBTQ+ Americans over the past decade.

“I think the main take home, frankly, is what has not happened,” says Professor Eskridge. “The main gains have been consolidated on both sides. Gay marriage is here to stay. There are now more than a million couples. There’s no way they can touch Obergefell, and there’s simply no effort to revisit that issue. LGBTQ families are here to stay, the lesbian baby boom is still going on in adoption, and most states now have second-parent adoption ideas for both straight and gay couples.”

The number of wedding vendors who would want to exclude LGBTQ+ people is small, and in general, “there doesn’t seem to be hordes of religious people who want to persecute gay people,” he says. “And part of my argument is that religion is changing as much as the country is, and in very distinctive ways.”

Indeed, according to the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2022 American Values Survey, wide majorities of every major religious group support nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people. This includes 80% of white and Hispanic Catholics, 78% of mainline Protestants, and 74% of Black Protestants. Even among white evangelical Protestants, 60% say they favor nondiscrimination protections for LGBTQ+ people.

Legislation targeting trans Americans

Even so, Professor Eskridge and others have been surprised by the intensity of recent legislation to outlaw transgender health care in conservative states.

“I am scared in a way that I haven’t been before,” says Deepak Sarma, professor of religious studies at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, who uses the pronouns they and them. “Since I’m genderfluid, people can’t always figure out what my gender is. And in certain places in Cleveland, I feel OK about that. But in other places, I put a hoodie on, and I try to look like I’m, like, more masculine.

“I have to be careful about what I’m going to wear, where I’m going to go,” they continue. “So do I think things have gotten better? I think things have gotten so much worse.”

Ms. Pizer also has found the recent legislation and legal fronts “such a surprise, and a frustrating surprise,” given the history of religious movements in ending discrimination in other areas of American life.

“Religious leaders of multiple different traditions and ethnic backgrounds and races participated in the social and political push to end racial segregation based on their religious values – it was very much a part of the call to end that practice,” she says. “The recognition that the religious values of love and welcoming the neighbor and embracing each other across differences, values that are so important for some religions – for some people, these haven’t seemed to apply the same way with respect to LGBTQ people.”

Roberts court’s focus

While the Roberts court has fiercely protected the needs of religiously conservative Americans, its jurisprudence has shifted profoundly from the concerns of other courts, says Professor Wuest at Mount Holyoke.

“Whereas many 20th century religious liberty decisions were made on behalf of unpopular religious minorities like Jehovah’s Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists, the Roberts Court frequently protects religious merchants seeking to deny service to LGBTQ+ customers and publicly-funded religious social service agencies refusing to place foster and adoptive children with LGBTQ+ married couples,” Professor Wuest says in an email.

The Roberts court has redefined the meaning of the First Amendment’s establishment clause, often referred to as the basis of “the separation of church and state,” by opening the door for public funds directed to private religious schools and allowing the public religious expressions of public school employees. It also permitted religious monuments with historical significance to continue to be displayed on government property.

It has also ruled that closely held for-profit corporations have the right to the free exercise of religion, which allows them to refuse to provide birth control health benefits for their employees. It also allowed religious adoption agencies receiving public funds to decline to work with same-sex couples.

And while the decision to overturn Roe v. Wade a year ago was not a religious liberty case, opposing the constitutional right to abortion had long been a top priority for most religious conservatives. The Roberts court, whose conservative majority is itself dominated by religious conservatives, provided their decadeslong efforts to erase the right to abortion with a resounding legal victory.

“Around the country, there has been a backlash to the movement for liberty and equality for gender and sexual minorities,” wrote Justice Sonia Sotomayor in a dissent Friday joined by Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson. “New forms of inclusion have been met with reactionary exclusion. This is heartbreaking. Sadly, it is also familiar. When the civil rights and women’s rights movements sought equality in public life, some public establishments refused. Some even claimed, based on sincere religious beliefs, constitutional rights to discriminate. The brave Justices who once sat on this Court decisively rejected those claims.”

What court’s rejection of student loan relief means

The Supreme Court’s rejection of President Joe Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan could affect millions of borrowers – and curtail the powers of the presidency.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

-

Ira Porter Staff writer

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

The Supreme Court’s rejection of President Joe Biden’s student loan debt relief plan will dash the hopes of millions of borrowers, while bolstering the efforts of the high court’s conservative majority to curtail the powers of the presidency and the executive branch administrative state.

Last August, President Biden promised to forgive $10,000 in student debt for an individual earning less than $125,000, or $250,000 per household. Students who had received Pell Grants for low-income families would have received more.

As his power to do so, he cited the HEROES Act, an educational relief act passed in the wake of 9/11 and subsequently expanded by Congress. As president, Donald Trump had cited the act as justification for pausing student loan payments during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Writing for the 6-3 Supreme Court majority, Chief Justice John Roberts said that stretching the HEROES statute to justify debt elimination was an overreach of executive power. It was much more than simply waiving or modifying loan payments, as the law allows.

The ruling is the latest example of the court fleshing out its new, and vague, “major questions” doctrine. This doctrine holds that the executive branch can’t regulate in areas of major importance without explicit approval from Congress.

“The question here is not whether something should be done; it is who has the authority to do it,” wrote Chief Justice Roberts for the court’s majority in the case.

What court’s rejection of student loan relief means

The U.S. Supreme Court today nullified President Joe Biden’s federal student loan relief plan, a decision that reinforces the high court’s muscular policing of the limits of executive power while plunging millions of borrowers around the country into financial uncertainty.

Within hours, President Biden – who had campaigned on forgiving federal student debt – announced new actions on student loan relief. But the new actions will likely face legal challenges, and they will have to survive review from a high court skeptical of executive action in the area.

Expanding on a pandemic-era temporary freeze on federal student loan payments, last year the Biden administration launched a program aimed at providing up to $20,000 in federal student loan relief for eligible borrowers. The administration cited the HEROES Act, a higher education assistance law that Congress passed in the aftermath of 9/11, as justification for the program, which the Congressional Budget Office found would cancel about $430 billion in debt principal.

High court justices struck down the program with their last two decisions of the current term. While they ruled unanimously that two borrowers who didn’t qualify for the plan didn’t have authority to challenge it, they ruled 6-3 along ideological lines that the plan harmed the state of Missouri through a loan servicing agency the state created.

And while the court’s substantive ruling was in some sense narrow, it’s the latest example of the court fleshing out the relatively new, and vague, “major questions” doctrine. The doctrine holds that the executive branch can’t regulate in areas of major importance without explicit approval from Congress.

“The question here is not whether something should be done; it is who has the authority to do it,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion.

The administration “asserts that the HEROES Act grants [it] the authority to cancel $430 billion of student loan principal,” he added. “It does not.”

Angela Wynn, a mother of five and director of stewardship and donor relations at Tennessee State University in Nashville, had been hoping it did.

Before getting married and moving to the Volunteer State, she’d been a single mother of three in Washington, D.C. After getting a bachelor’s degree there, and a master’s degree online, she now owes $64,000. After she saw the Supreme Court ban affirmative action in college admissions yesterday, another decision disadvantaging people of color – Black students start out with more debt than white students, and pay it down more slowly, multiple reports have found – today’s news doesn’t surprise her.

“I was disappointed, but definitely not shocked,” she says.

The debt relief program “was a great idea,” she adds, “but unfortunately we know how the system works, and it’s not always to our benefit, and this would have benefited us the most in terms of closing that wealth gap.”

Student loans and the French Revolution

National student loan debt increased from about $500 billion to $1.7 trillion between 2006 and 2020, according to the Education Data Initiative, with rising tuition rates affecting generations of students who see a college degree as the surest route to a middle-class life.

President Biden entered office having pledged to cancel at least $10,000 in federal loans per person. The day before he announced the debt relief program last year, the Department of Justice issued a memorandum saying that the HEROES Act vests the administration “with expansive authority to alleviate the hardship” of federal student loan recipients as a result of emergencies.

Within months of this announcement, multiple lawsuits had been filed challenging the program. The two challenges that reached the Supreme Court came from a pair of individual borrowers and a coalition of six states, including Missouri.

The court rejected the individual borrowers’ challenge on procedural grounds, writing in a short, unanimous opinion that they couldn’t prove they suffer an injury “fairly traceable” to the debt relief program. The second challenge, brought by the states, resulted in a more substantive ruling.

The states also faced a notable procedural question. Specifically, did the state of Missouri have standing to sue because the debt relief program would financially harm MOHELA, a state-created but independent loan servicing agency? Chief Justice Roberts wrote that because the agency is “an instrumentality” of the state of Missouri, direct harms to the agency also directly harm the state.

But in dissent, Justice Elena Kagan noted that MOHELA doesn’t pass any losses from loan cancellations on to the state. She also noted that MOHELA did not challenge the debt relief program itself, and didn’t even cooperate with Missouri’s lawsuit.

“The separateness, both financial and legal, between MOHELA and Missouri makes MOHELA alone the proper party” to bring this suit, she wrote.

“Where’s MOHELA? The answer is: As far from this suit as it can manage,” Justice Kagan wrote.

Standing doctrine typically requires a party to have suffered a concrete injury to bring a lawsuit, she added. In this case, “the Court ignores that principle in allowing Missouri to piggy-back on the ‘legal rights and interests’ of an independent entity.”

The court’s six-justice conservative majority disagreed, however, and the majority further held that the Biden administration had exceeded its authority in launching the debt relief program. Primarily, the court found that the secretary of education’s actions exceeded the plain language of the HEROES Act.

The act allows the secretary of education to “waive or modify” provisions of federal student assistance programs in connection with a national emergency.

But the debt relief program modified the act “only in the same sense that ‘the French Revolution “modified” the status of the French nobility’ – it has abolished them and supplanted them with a new regime entirely,” wrote Chief Justice Roberts.

The Biden administration also ran afoul of the major questions doctrine, the court ruled. The court relied on the doctrine – which holds that federal agencies can’t take major actions without clear legal approval from Congress – in a controversial decision last term, striking down an Obama-era climate regulation.

The doctrine was not as central to the decision nullifying the student debt relief program, but Justice Amy Coney Barrett devoted a separate opinion to defending the majority opinion and downplaying the potential breadth of the doctrine.

“The major questions doctrine has an important role to play when courts review [major] agency action,” she wrote. But “our decision today does not ‘trump’ the statutory text, nor does it make this Court the ‘arbiter’ of ‘national policy.’”

Decision fallout

The court’s ruling is narrow in the sense that it doesn’t preclude all forms of federal debt relief from the executive branch. But a short-term consequence will be financial shocks for many student borrowers, says John Pelletier, director of the Center for Financial Literacy at Champlain College.

“We’re going to see a reduction in the average credit scores across the country,” he adds, and student loan default rates could reach levels higher than after the Great Recession.

And it’s not like a legal challenge, or even a legal defeat, should have been a huge surprise. Trump administration lawyers had advised in 2020 that the executive branch couldn’t forgive student loans.

“Lawyers that worked for the Biden administration knew, or should have known, that where we are today is probably where we would end up,” says Mr. Pelletier. “My concern is, did people rely on this and make decisions that are going to hurt them economically?”

Biden response

Hours after release of the Supreme Court decision, President Biden appeared in the White House and said that the decision “has closed one path. ... Now we’re going to try another.”

Mr. Biden said that the Department of Education will establish a new “ramp” repayment program for borrowers who will be forced to resume payments on their loans due to the end of the pandemic-era pause. Under this program, the Department of Education will not refer delinquent borrowers to collection agencies for at least 12 months, so they have time to get their finances in order.

The president also said his administration would explore a new legal pathway consistent with the Supreme Court ruling to allow loan forgiveness for “as many borrowers as possible.”

This new attempt will be based on a different statute, the 1965 Higher Education Act, he said.

Mr. Biden added that he disagrees with the court’s ruling, in particular its implications for restraining executive power.

“I think the court misinterpreted the Constitution,” he said.

His comments echoed Justice Kagan’s dissent, which criticized the major questions doctrine as a way for the Supreme Court to hold an effective veto power over executive branch policies.

“The Court once again substitutes itself for Congress and the Executive Branch – and the hundreds of millions of people they represent – in making this Nation’s most important, as well as most contested, policy decisions,” she wrote.

Court watchers have a more mixed view of how the justices used the doctrine in this case – and how the doctrine could be used in the future.

“It’s fair to read the opinion in that case [last term] as having relied primarily and heavily on the major questions doctrine,” said Jack Fitzhenry, a legal fellow at The Heritage Foundation, during a press briefing.

“The court took pains in this decision in a way it did not in [that one] to analyze the statute on its own terms, kind of independent of the major questions doctrine.”

The court is increasingly using the doctrine to narrow the scope of administrative power, says Derek Black, a professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law. But narrowing power in one area may be broadening it in another, like the Supreme Court.

“The idea that this little ant hole provision in a statute produces sort of elephant-sized power is something the court is skeptical of,” he adds. “It also means that the court’s interpretation becomes incredibly important.”

For Ms. Wynn, the mother in Tennessee, the decision means worrying about sending her children to college while she’s still having to pay for her own education. Because of the size of her family, they need seven-seater vehicles, and gas is almost $4 a gallon where she lives. She buys cheaper generic brands at grocery stores, but her grocery bill has doubled.

“It’s like every time there’s something being pushed to the forefront to help this country to get back to where it should be – and that is not having this huge wealth gap between the super wealthy and everyone else – it just gets ripped away from us,” she says.

“The middle class is disappearing so fast,” she adds. “All of us were hoping that this would [not] happen, but it was cautious optimism.”

Why Russia crisis requires US vigilance

Seen from the United States, Russia’s internal crisis creates a period of uncertainty that could affect events beyond Russia’s borders. The challenge for the U.S.: to balance its concerns with an openness to military and diplomatic opportunities.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Western leaders are being careful to frame the mutiny launched a week ago by mercenary leader Yevgeny Prigozhin as an internal Russian matter, and to remain cautious in their assessments. Russia’s crisis “is a moving picture, and I don’t think we’ve seen the last act,” was as far as U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken would venture in comments Wednesday at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

However, senior U.S. officials and analysts say Washington should anticipate that President Vladimir Putin will seek to reassert his control and move to reestablish a perception of Russia as a power to be reckoned with. The United States, they say, must prepare for a world where a major nuclear power is unstable and threatening.

The crisis in Russian leadership “is not over. It may have only started, and that means greater uncertainty, more instability, and therefore we are reaching a point of maximum danger,” says Ivo Daalder, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO.

Yet others note that the crisis creates military and diplomatic openings as well.

“What I really hope,” says Seth Jones, at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, “is that NATO leans forward on taking advantage of Russian weaknesses right now to push in Ukraine.”

Why Russia crisis requires US vigilance

What to do about the 24-hour mutiny launched a week ago by Wagner mercenary group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin is an internal matter for Russians alone to address – as President Joe Biden and other Western leaders have made a point to affirm.

However, the repercussions of such a revealing and – for Russian President Vladimir Putin – embarrassing and destabilizing event are virtually certain to spill over Russia’s borders, senior U.S. officials and international affairs analysts say.

The United States, these officials and analysts add, should anticipate that a weakened Mr. Putin will continue to seek to reassert his control over what looked to many during the crisis like a Potemkin state, and move to reestablish a perception of Russia as a power to be reckoned with.

The U.S., therefore, must prepare for a world where the keeper of the largest nuclear arsenal is unstable and threatening.

The crisis in Russian leadership “is not over. It may have only started, and that means greater uncertainty, more instability, and therefore we are reaching a point of maximum danger,” says Ivo Daalder, a former U.S. ambassador to NATO who is now president of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

“The concern for the U.S. and others as well is that Russia is turning into an irregular, unpredictable, and rogue-like state,” he says. “The outcome we have to prepare for is that a weaker Russia will try to reassert itself by lashing out with more roguish activities,” he adds. “That is why this is such a dangerous time.”

Helping Ukraine

The U.S. should also be seizing on the moment as an opportunity, others say: to do more for Ukraine, for example, as it pursues its counteroffensive to take back as much Russian-occupied territory as possible.

“What I really hope … is that NATO leans forward on taking advantage of Russian weaknesses right now to push in Ukraine,” says Seth Jones, director of the International Security Program and Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington. “This [moment] does present an opportunity to provide a range of assistance on the battlefield.”

Others in Washington hold similar views.

“We should take steps to help the Ukrainians take advantage of the confusion in the upper echelons of the Russian military,” says Luke Coffey, a senior national security fellow at the Hudson Institute in Washington. “Of course there are things we can do now to help Ukraine win on the battlefield.”

Moreover, he adds, the U.S. should prepare for the “coming chaos in Moscow” by stepping up diplomatic outreach to Central Asian countries bordering Russia – like Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan.

The “roguish activities” that some like Ambassador Daalder foresee a weakened Russia resorting to could have global implications.

For starters, there is the nuclear threat – something Mr. Putin has already dangled before the world’s eyes, notably last fall as Ukraine’s initial counteroffensive in Russia’s war was making impressive gains. Mr. Putin hinted that Russia, with more than 5,000 nuclear warheads, could be pushed to use tactical nuclear weapons in the fighting.

Ukrainian officials, who have fresh in mind the catastrophic collapse this month of the Nova Kakhovka Dam, are warning Western partners that Russia could destroy the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant it controls on occupied Ukrainian territory.

Authorities in Finland say they are seeing signs that Russia may be planning to resort to disinformation and other unconventional methods to foment instability on the two countries’ long border.

Even the already acute global food security crisis could be further exacerbated by steps a wounded Russia could take, some warn – like ending the United Nations-brokered grain deal that has allowed Ukrainian grains to reach key African and Middle East markets.

NATO summit

Senior U.S. officials have been very careful in their comments on the Russian leadership crisis and the potential steps the U.S. could take in response.

Russia’s crisis “is a moving picture, and I don’t think we’ve seen the last act,” was as far as Secretary of State Antony Blinken would venture in comments Wednesday at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York. Mr. Putin “has a lot of questions to answer,” Secretary Blinken noted, while adding that the U.S. before this crisis was already focused on confronting a “revanchist Russia.”

But he has also hinted this week that the U.S. and NATO will both be announcing new assistance and cooperation measures with Ukraine in the context of the alliance’s summit in Vilnius, Lithuania, next month.

That new assistance could very well include the ATACMS long-range missile system Ukraine has long pressed Washington to provide, Dr. Jones says, as well as accelerated steps for providing Kyiv with F-16 fighter jets.

Looking more long-term, NATO was already expected to offer Ukraine some form of security partnership short of membership at its summit. But events in Russia underscore the urgency of such a step, some say, and are likely to bolster support for moving forcefully in that direction.

Beyond Ukraine, Russia’s sudden instability and unpredictability have almost certainly moved Russia up on the NATO summit agenda, Ambassador Daalder says. Among other things, plans already in the works for reinforcing alliance-wide defenses, especially in the Baltics and Eastern Europe, will be treated with greater urgency.

“Military alliances are in the business of preparing for worst-case scenarios … and what the recent Prigozhin affair and the fallout proves is that this regime is actually a lot more fragile and unstable than we perhaps previously thought,” says Sean Monaghan, visiting fellow in the CSIS Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program.

“NATO’s job is to have a range of defense plans for a range of contingencies,” he adds, “and I think this will be a big focus at Vilnius.”

Engaging China

Then there is the matter of China and what President Xi Jinping has said is his country’s “unbreakable” strategic partnership with Mr. Putin’s authoritarian Russia.

Now that the U.S.-China dialogue has come out of the deep freeze following Secretary Blinken’s recent trip to Beijing, the U.S. should be laying out for an order-craving and image-conscious China why a tight bond with Russia may not be in its best interests.

“We should remind the Chinese that with friends like these, who needs enemies?” says Ambassador Daalder. Citing Mr. Putin’s use of nuclear blackmail or Russia’s mounting war crimes and human rights violations “can encourage them to think about how they may be linking themselves to behavior they ultimately don’t want to be associated with,” Ambassador Daalder says.

Nevertheless, Mr. Coffey at Hudson says Washington has to remember that in some ways China is benefiting from Russia’s weaknesses in the wake of its disastrous foray into Ukraine – for example, by the access Beijing has had to discount-priced Russian energy.

Yet, beyond all that, it might be enough just for Washington to point out how recent events suggest a prolonged period of instability in Russia, Ambassador Daalder says.

“I think we should say that on top of everything else, Russia is unstable to boot,” he says. “And that’s the one thing the Chinese worry about most.”

Reparations in California: What can lawmakers achieve?

California is the first U.S. state to take steps toward reparations for harms caused by slavery and institutional racism. With a sweeping report from the state task force, it’s now up to state lawmakers.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

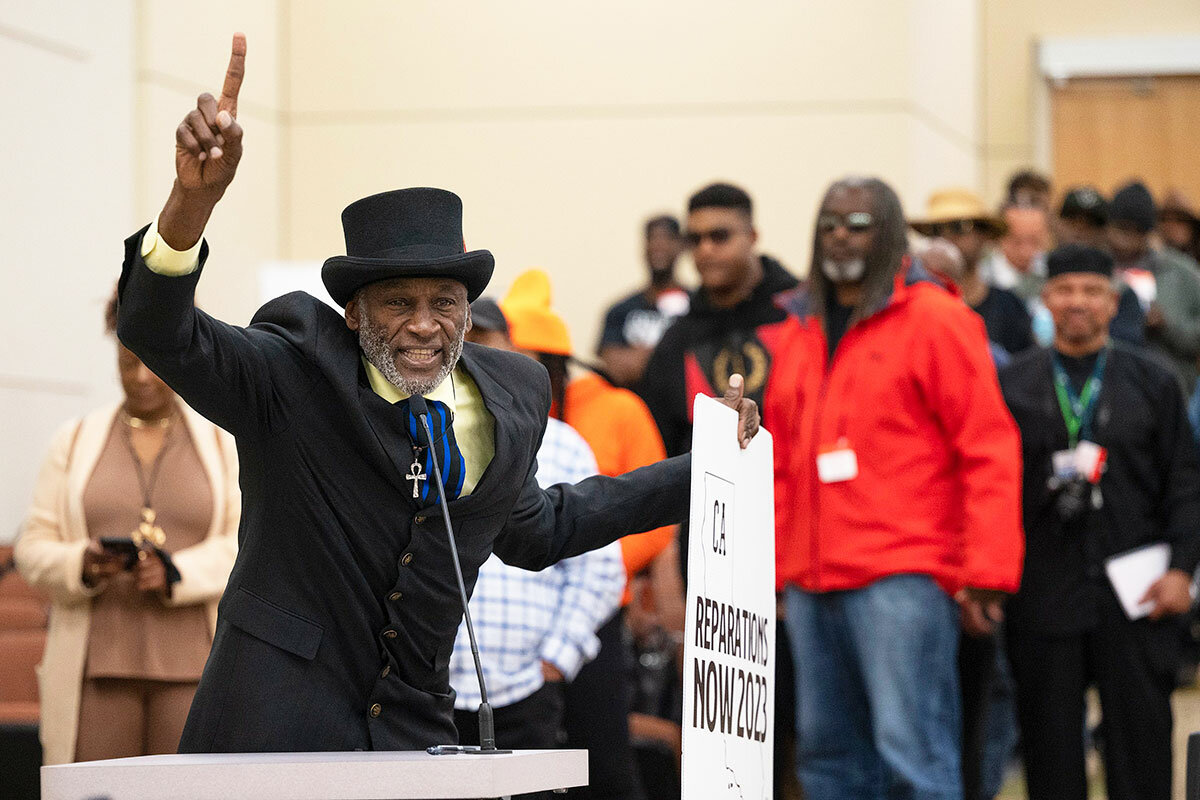

The California Reparations Task Force on Thursday delivered a final report with sweeping recommendations for financial, legislative, and administrative steps toward closing racial gaps in wealth, health, and opportunity.

The nine-member task force, appointed by the governor and legislature, spent two years on its 1,100-page report – the first attempt by a U.S. state to take up the issue of reparations to Black residents. Those involved hope it will become a template for other states.

State lawmakers and most Californians acknowledge a history of violence and racism in need of correction, in a state not generally linked with slavery. But there’s no consensus on how best to do that, and now lawmakers begin the complex work of administering justice.

In a large and demographically diverse state, the work of delivering myriad legislative reforms is politically fraught, especially when the state is tackling a $32 billion shortfall.

State Senator Steven Bradford, a member of the task force and vice chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus, does not expect immediate legislative action. He references Martin Luther King Jr.’s counsel to “accept the finite disappointment and yet cling to the infinite hope.”

“I’m hopeful that this state will do the right thing,” says Mr. Bradford, “but I enter this with the understanding that disappointment will probably be a part of it. ... So I have infinite hope that at some point, this country will recognize its original sin. And that was slavery.”

Reparations in California: What can lawmakers achieve?

How do you put a price on slavery’s continuing harm? That question is what California lawmakers will take up now that a historic report, released yesterday, has landed – with sweeping recommendations for financial, legislative, and administrative steps to take toward closing racial gaps in wealth, health, and opportunity.

State lawmakers and most Californians acknowledge a history of violence and racism in need of correction, in a state not generally linked with slavery. But there’s no consensus on how best to repair, and now lawmakers begin the complex work of administering justice that heals the past and recalibrates fairness moving forward.

Implementing the report in its entirety would overhaul state government and the distribution of public resources. But in a demographically diverse state with 40 million people, 6.5% of them Black residents, the work of delivering myriad legislative reforms – while the state tackles a $32 billion shortfall – is politically fraught for this Democratic supermajority.

“Although it would be foolish to downplay the historical and unconscionable discrimination against African Americans, how would an attempt to provide cash or other tangible reparations to only that one aggrieved group sit with the general population?” asks veteran Democratic strategist Garry South. “My bet is it wouldn’t sit very well.”

The nine-member Reparations Task Force, appointed by the governor and legislature, spent two years on its 1,100-page report – the first state in the nation to do so – with the hope of those involved that it will become a template for other states.

The task force sunsetted Thursday, with a final vote and comments from members and allies who insisted the report’s full implementation is both justifiable and achievable. A calculator to determine cash payouts was made public in May, and it grabbed headlines with the suggestion that over 2 million Black residents could qualify for anywhere between a few thousand and a million-plus dollars each. But the recommendations go beyond direct payment, suggesting reforms in education, banking, policing, prisons, health care, business, voting rights, infrastructure, and the state constitution, plus a California African American Freedmen Affairs Agency to manage reparations long-term.

Experts and lawmakers acknowledge the estimated $800 billion needed for cash payments alone is beyond available funding. “It would not be politically tenable even in a state this liberal ... to start doling out cash money to any particular ethnic group for past wrongs,” says Mr. South.

At more than 2.5 times the state’s annual budget, that price tag may be the biggest – but not the only – hurdle.

Legislative action

The report is a guide for lawmakers, who are responsible for working out details and funding. They are waiting until they have the recommendations in hand to decide the next steps, which could involve years’ worth of legislative proposals and amendments.

The wide-ranging suggestions span a dozen categories and include:

- State-subsidized mortgages that guarantee low interest rates to qualified Black homebuyers.

- Free tuition for Black students attending California colleges and universities.

- Resources shifted away from law enforcement to support health care, youth development, and job training.

- Funds for planting trees in Black neighborhoods to minimize “heat islands.”

Party leaders hesitate to give a time frame for legislative action. Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas takes the leadership position at the same time the report lands with lawmakers, and he declined to comment on it. Senate President Pro Tempore Toni Atkins says in an email she will be “carefully examining” the report and calls it “an important step in California’s efforts to confront a history of injustice and inequality for Black Americans.”

Republicans, who hold 18 Assembly seats to Democrats’ 62, agree the state needs to deal with racial inequities. Minority Leader James Gallagher calls slavery a “terrible stain” on America’s history and says, “We stand ready to find areas of agreement that will improve the lives of Black Californians.” But he also calls monetary reparations unfeasible. “Nor do I think it’s fair to ask new immigrants and low-income folks in this state to pay for reparations,” he says.

Advocates and task force members forecast a long road ahead. State Senator Steven Bradford, vice chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus, is one of two lawmakers – along with Assembly Member Reginald Jones-Sawyer – who served on the task force. He does not expect immediate action.

Multigenerational change

The harm done to Black Californians was “multigenerational, so the repair must also be multigenerational,” according to Chris Lodgson, president and lead organizer for the Coalition for a Just and Equitable California. The group is one of seven community organizations working with the task force to help educate the public about reparations. Noting commitments from both Senator Bradford and Assembly Member Jones-Sawyer, Mr. Lodgson expects to see legislation introduced in 2024, and for reforms “to be a multigenerational effort as it relates to enactment, implementation and evaluation,” he wrote in an email.

Californians generally agree that racism is a problem in the United States (about 80%) and that racial and ethnic discrimination contributes to economic inequality (more than 70%), according to a recent survey by the nonpartisan Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC). There’s less agreement on how to address those inequities, and only 43% of residents had a favorable opinion of the task force.

“Is there something to build on in terms of support? Yes. Is there the political will? We’ll find out,” says Mark Baldassare, survey director at PPIC, who points out that public opinion often shifts when elected leaders speak out on specific issues.

Senator Bradford agrees the future for reforms is unpredictable. “I’ve done this long enough to know that ... the most common sense measures many times run into the greatest amount of roadblocks. So I’m mindful of that and I’m not gonna be naive enough to think, ‘oh, yeah, this is very simple and everybody would agree upon it’ because that usually doesn’t happen,” he says.

A “free” state

California entered the Union in 1850 as a free state but two years later passed a Fugitive Slave Act, which threatened Black people who thought they could go West to escape enslavement. Subsequent laws suppressed Black voters, segregated schools, and barred Black people from courtroom justice. Black veterans were kept from accessing benefits promised in the 1944 G.I. Bill, which provided low-interest mortgages and business loans, as well as college tuition. Black homeownership was hindered by mortgage discrimination, redlining practices, sundown laws, and race-based zoning ordinances.

Today, white Americans hold 10 times more wealth than Black Americans, according to a recent study by the Rand Corporation. Task force members cite a $360,000 per-person wealth gap.

Lawmakers and reform advocates say it’s too early to determine which injustices will be prioritized. In May, Gov. Gavin Newsom declined to back any specific measures and released a statement that said, “Dealing with that legacy is about much more than cash payments.”

Some reforms are in the works or have failed once already, like an amendment to the state constitution to end forced prison labor.

Healing won’t begin without a formal apology, says Mr. Bradford – a descendant of chattel slavery himself. “This country has yet to apologize for slavery. And that’s a first step,” he says. “You can’t address harms until you first apologize for the wrongs.”

For Mr. Lodgson of the equity coalition, success will look like swift implementation of the full report, complete with financial payouts and a fully funded reparations agency.

But Mr. Bradford is more tempered, referencing Martin Luther King Jr.’s counsel to “accept the finite disappointment and yet cling to the infinite hope.”

“I’m hopeful that this state will do the right thing,” says Mr. Bradford, “but I enter this with the understanding that disappointment will probably be a part of it. ... So I have infinite hope that at some point, this country will recognize its original sin, and that was slavery.”

This story was produced as part of a special Monitor series exploring the reparations debate, in the United States and around the world. Explore more.

Podcast

Our writers’ takeaways from digging into reparations

There’s more to the reparations discussion than what typically makes the news. Two Monitor writers – one white, one Black – found that many, on both sides of the issue, care deeply about honestly acknowledging history. On this week’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast.

California’s Reparations Task Force has finalized its report to the state legislature. It’s the first such statewide report, but it lands in a conversation already well underway.

Bringing insights to that conversation are Monitor writers, including Clara Germani and Maisie Sparks. They discussed their recent stories – and the challenges that came with them – on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast.

“This is a really tricky balance to do a story about white people and reparations,” Clara says. “I had to be very aware of the words I was choosing, the way I was posing questions.”

Clara discovered that, despite polls showing that 80% of white people oppose reparations, there’s a lot of grassroots action occurring. Millions of dollars are being transferred, without fanfare, to the Black community for housing, education, and business support programs. But she also found that reparations aren’t just about money. Of nearly 500 programs she saw online, most sought instead to memorialize and acknowledge.

In speaking with descendants of those enslaved at St. Louis University, Maisie discovered something similar. While money is a concern, it’s far from the sole focus. After learning about their ancestors’ lives, the descendants were determined to honor and recognize their ancestors, who have been left out of the university’s history. A key goal was to acknowledge what had happened and start to bring some kind of justice that will move us into the future.

“I know that a lot of people get ticked off by a more panoramic view of our nation’s history,” Maisie says on the podcast. “And so that caused me a little concern initially, but I realized that I did have to set it aside. It’s a story that needs to be told.” – Trudy Palmer and Jingnan Peng

Find a transcript and show notes, with story links, here.

Reckoning With Reparations

Books

In search of summer beach reads? Read on.

Our picks for delightful beach reads include six witty and unexpected books, starring the Pony Express, fantastical dragons, and a formidable Chinese pirate queen.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When it comes to summer reading, I firmly believe there is no right answer. If you’re at the beach and you’re reading it, it’s a beach read.

For summer 2023, people are seeking a sense of adventure and reconnection – and, let’s be honest, we all could use a good laugh. We’ve got you covered with a book club read, a BookTok author, real-life adventure, fantasy, mystery, and a novel that can make you snort-laugh poolside. We’ve also got a pirate queen.

The Pony Express existed only 18 months, but it has endured in the imagination much longer. In “The Last Ride of the Pony Express,” Outside magazine contributor Will Grant sets out with his horses Chicken Fry and Badger to follow the 2,000-mile trail so dangerous that one historical advertisement allegedly read, “Orphans preferred.”

If you’d prefer historical fiction with more emphasis on the fiction – and 100% more piracy – pack Rita Chang-Eppig’s debut, “Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea.” Nineteenth-century pirate queen Shek Yeung ruled the South China Sea at a time when women were not allowed to chart their own path. Shek is a vibrant, complicated heroine who was sold into sexual slavery as a teenager, only to win her freedom and captain half a fleet.

In search of summer beach reads? Read on.

When it comes to summer reading, I firmly believe there is no right answer. If you’re at the beach and you’re reading it, it’s a beach read.

My son celebrated the end of his junior year of college with “Heart of Darkness” (confession: Joseph Conrad does not scream “pleasure reading” to me) and then moved on to Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” and “The Rest Is Noise” by New Yorker music critic Alex Ross.

His parents are, comparatively speaking, lightweights. My husband is happily working his way through “The Pot Thief” series (no, not that kind of pot) by J. Michael Orenduff. The comic mysteries serve up Southwest culture, archaeology, excellent food, and plenty of Hatch chiles, and they remind Brian of his desert childhood.

This summer I’m finally diving into “H Is for Hawk” and “The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue.” (Perils of a reviewer: There are so many new books that if you don’t make time to circle back, you never catch up with the ones you weren’t assigned.)

When it comes to summer 2023, people are seeking a sense of adventure and reconnection – and, let’s be honest, we all could use a good laugh. We’ve got you covered whether you’re interested in a book club read, a BookTok author, a real-life adventure, a fantasy, a mystery, or a novel that can make you snort-laugh poolside. We’ve also got a pirate queen.

Pony Express redux

The Pony Express existed only 18 months, but it has endured in the imagination as an institution for much longer than riders carried the mail via horseback from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. “It was the greatest display of American horsemanship to ever color the pages of a history book,” writes Outside magazine contributor Will Grant. (Only one mailbag, called a mochila, was lost.) Grant sets out to follow their trail in his new book, “The Last Ride of the Pony Express,” covering 2,000 miles with his horses Chicken Fry and Badger. Grant, who spent his youth working with horses, gives the trio 100 days rather than the 10-day relay route so dangerous that one advertisement allegedly read, “Orphans preferred.” In addition to the miles, he also covers the philosophy, history, and environment of the American West and how the land shaped a people.

Summer school satire

For a far more irreverent take on U.S. history, and with a sincere apology to any high school student actually studying for the Advanced Placement exam, Washington Post humorist Alexandra Petri creates the Americana she wished existed. “Alexandra Petri’s US History: Important American Documents (I Made Up)” offers essays ranging from “How To Pose for Your Civil War Photograph,” to Elizabeth Cady Stanton getting pulled involuntarily into a Hallmark movie when she traveled to Seneca Falls. (Any career-minded woman who ventures to a small town is doomed to be trapped in a sweet and probably snow-filled future.) There’s a new take on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow that tries to be more accurate about who actually warned that the British were coming. (Editor’s note: Longfellow never let a name or a fact get in the way of a poem.) Petri knows her stuff – readers are advised to check out the footnotes – and some of the most absurd flights of history are, in fact, true.

A legendary Chinese pirate queen

If you’d prefer a combination of fiction and history with more emphasis on the fiction – and 100% more piracy – pack Rita Chang-Eppig’s debut, “Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea.” Nineteenth-century pirate queen Shek Yeung ruled the South China Sea at a time when women were not allowed to chart their own path. Shek is a vibrant, complicated heroine who was sold into sexual slavery as a teenager, only to win her freedom and captain half a fleet. Chang-Eppig starts her epic in the middle of a battle, when Shek’s pirate husband is killed. The novel then moves backward and forward through time, as the master strategist begins the fight for her own life and her children – a survivor who refuses to live life on anyone else’s terms again.

A tangled murder mystery

If, like me, you’ve needed a mystery handy since the pandemic to help restore your sense of order, author Elly Griffiths’ character, Ruth Galloway, can relate. The British forensic archaeologist “feels that she has been fighting things – Covid, the university, her own feelings – for too long,” writes Griffiths in “The Last Remains,” the conclusion to her well-loved and long-running series. Ruth’s university plans to shut down her department to cut costs, and Ruth is trying to summon the energy for one more battle. (“We need to fight back, David texted. I’m starting a Twitter account.”) Meanwhile, a skeleton has been found behind a bricked-up wall in a pub – a traditional punishment meted out to erring women. Cathbad, Ruth’s friend, not only knew the dead woman but also suddenly vanishes, leaving Ruth, Detective Chief Inspector Harry Nelson, and Cathbad’s family distraught with worry. A careful craftswoman, Griffiths brings back characters from earlier mysteries, and the novel chimes with echoes that reach back to Ruth’s first outing, “The Crossing Places.” While I got a little weary of the romance a few books ago, Ruth and her found family remain good company, and Griffiths offers up the historical detail that has enriched each mystery. (Nicola de la Haye, 12th-century castellan and savior of England, is someone I’m happy to know about.)

Finding grace in grief

In a country as bad at mourning as the United States, it’s hard to think of a novelist who handles grief with more gentleness than Steven Rowley. He follows up his utterly charming “The Guncle,” in which the main character steps in to care for his niece and nephew after the death of his sister, with “The Celebrants.” Five college friends vow to be there for each other at their lowest moments in life by throwing funerals. The point is simple: when life gets really hard, “to remind you that you are loved.”

They drop everything and fly 3,000 miles when parents die, when a marriage fails, when an honest mistake is about to send someone to prison. When you can’t find the light in your own life, “it’s someone else’s turn to hold the lantern.” The marketing copy calls it a Gen X “Big Chill,” but Rowley himself nails the vibe as “four funerals and a wedding.” Some of the situations are a little forced – a destination funeral, a surprise funeral – but then, what memorial service isn’t staged, with the celebrants unsure how to act or what to say?

Rowley’s repartee is witty, and the importance of making sure those you love know how much they mean to you comes through on every page.

Dragon-filled fantasy

Speaking of friendship, every reader should have a book friend in their life. Mine handed me “Fourth Wing” by Rebecca Yarros with the admonition that I shouldn’t look it up or read any reviews. This was sage advice. If you loved the series “The Dragonriders of Pern” but cringed at the consent issues, hie thee to a bookstore. Here be dragons! Violet Sorrengail survived a childhood illness that left her with weak joints and prematurely gray hair. She planned to live an indoorsy life as a scribe among her beloved books. Her general mom conscripts her into the fantasy equivalent of the Air Force Academy in which fellow students see weakness as a reason to kill you. Oh, and several of her classmates’ parents were executed on her mother’s orders. Be warned: There is a cliffhanger. It is a doozy.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Africa’s moment of truth after Russia’s mutiny

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The short-lived rebellion in Russia last weekend has raised uncertainty about the future of Moscow’s military influence in Africa, where the mercenary Wagner Group has been the forward arm of President Vladimir Putin’s strategic interests. For African leaders, however, the failed mutiny prompts a different question: Does the continent’s future rely more on guns or on the civic values of democracy?

The answer was unequivocal for more than 50 leaders from Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, who had gathered last week in Poland. Being merely pro-liberty is not enough, the group declared in a statement. “Defending democracy requires common purpose – of solidarity – among democrats inside and outside all countries.”

That consensus takes aim at a core tenet of Africa’s diplomacy – that the continent must resist choosing sides between great powers, such as the West and its global rivals. On the point of opposing Mr. Putin’s war of aggression, however, neutrality does not apply.

Africa’s moment of truth after Russia’s mutiny

The short-lived rebellion in Russia last weekend has raised uncertainty about the future of Moscow’s military influence in Africa, where the mercenary Wagner Group has been the forward arm of President Vladimir Putin’s strategic interests. For African leaders, however, the failed mutiny prompts a different question: Does the continent’s future rely more on guns or on the civic values of democracy?

The answer was unequivocal for more than 50 leaders from Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe, who had gathered last week in Poland. Being merely pro-liberty is not enough, the group declared in a statement. “Defending democracy requires common purpose – of solidarity – among democrats inside and outside all countries.”

That consensus takes aim at a core tenet of Africa’s diplomacy – that the continent must resist choosing sides between great powers, such as the West and its global rivals. That explains how Kenya could announce its intentions for a trade deal with Russia in late May and then, three weeks later, sign another deal with the European Union. It explains why nearly half of all African governments refuse to condemn Russia for invading Ukraine.

By staying neutral, African leaders argue, they can promote equality between richer and poorer nations and help broker peace in foreign conflicts. Yet pursuing ties simultaneously with countries that uphold democratic values and with those that undermine them has instead resulted in costly entanglements, intense foreign competition over strategic natural resources, conflict, and financial dependency.

Wagner’s spread across a handful of faltering countries, mostly concentrated in the Sahel region, has undermined efforts by France and the United States to strengthen professional African militaries under civilian command. “Its effect,” the United States Institute of Peace noted recently, “is to strengthen rule by force rather than by democracy and law [and] to promote corruption over transparency.”

Mr. Putin has said that Wagner’s roughly 5,000 personnel will stay in Africa. Moscow’s interests in Africa, ranging from resource extraction to a military base on the Red Sea coast of Sudan, have not changed.

But Africa’s determination to remain nonaligned now faces a pivotal test. South Africa is due in August to host the leaders of the so-called BRICS countries – including Brazil, Russia, India, and China. In March, the International Criminal Court issued arrest warrants for Mr. Putin. That puts South Africa, as a signatory to the ICC, under an obligation to arrest the Russian president if he attends the summit.

“I’m quite sure, we can’t say to President Putin, please come to South Africa, and then arrest him,” former South African President Thabo Mbeki told the South African Broadcasting Corp. in May. “At the same time, we can’t say come to South Africa, and not arrest him – because we’re defying our own law. ... We can’t behave as a lawless government.”

On the point of opposing a war of aggression, neutrality does not apply.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Magnifying God’s goodness

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

The more we acknowledge each expression of God’s goodness, the more we see and experience good in our lives.

Magnifying God’s goodness

William Shakespeare wrote,

This our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

And poet Piet Hein echoed him when he wrote,

He on whom

God’s light

does fall

sees

the great things

in the small.

I love these quotes. They point to the fact that as we take note of God’s hand at work, even in the minutiae of daily life, we are actually witnessing and magnifying God’s goodness.

The Bible says, “O magnify the Lord with me, and let us exalt his name together” (Psalms 34:3). I’ve found that this directive becomes a catalyst for the recognition of greater good in our lives as well as in the world. To me, magnifying God means that as one approaches God in thought, Deity becomes larger – more real, relevant, and present to us – in our lives. God is already ever-present Love, and magnifying Him enables us to be more aware of the divine goodness that exists right here, right now, and always. Because God, good, is ever present, and always aware of His own goodness, all of us, as the image or expression of God, have a spiritual awareness that naturally notices the divine presence.

This spiritual sense, which Mary Baker Eddy defines as “a conscious, constant capacity to understand God” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 209), is innate in all God’s children. This is what allows us to magnify Him. Where limited, mortal, material sense sees the irrelevant and mundane, spiritual sense sees the inspired and meaningful. So, the tender hand reaching out to a child, the friendly wave, the unselfish gesture, all magnify God’s presence.

Our ability to magnify God depends on which lens we are looking through, the human or the divine. Science and Health says, “We must look deep into realism instead of accepting only the outward sense of things” (p. 129). In doing this, I’ve found that even the most ordinary experiences become examples of God’s presence.

For instance, I had a favorite lamp that badly needed a new shade, but an exhaustive search for a replacement was unproductive. So I patched up the old one and moved on.

Months later, while out walking one morning, I was acutely aware of all the lovely evidences of God’s presence. In my prayers, I had been especially attentive to magnifying God’s goodness and each expression of this goodness in the world, rather than allowing myself to get caught up in the fear and sadness that seemed rampant in news reports. My “sermons in stones” that morning were seen in the dappled sunlight, the warm breeze – and suddenly in a lampshade! There it was in a neighbor’s front yard with a “FREE” sign on it. It was brand-new, with the wrapping still on it, and it was a perfect fit. A small example, but my desire to magnify God had opened my eyes to the meeting of a need.

While grateful for this find, I took a much deeper message away from it. Prayer isn’t about obtaining stuff or fixing problems; it’s about feeling God’s presence and loving care, which we all have the opportunity to do as His children.

Christ Jesus spoke of this care as pertaining to even the smallest details in our life when he said, “Are not five sparrows sold for two farthings, and not one of them is forgotten before God? But even the very hairs of your head are all numbered. Fear not therefore: ye are of more value than many sparrows” (Luke 12:6, 7).

The working out of the minute details of our lives may seem inconsequential, and yet each is evidence of the Father’s consistent care for His creation. If a need so insignificant as a lampshade is met, we can be grateful to know how much more the bigger things like supply, safety, and health are being met, too, as we continue to magnify God’s goodness.

Let’s joyously commit to utilizing our God-given spiritual sense to magnify God in all His ways, great or small. In this way, we will find Love’s healing goodness and the blessings it brings – to us and to a waiting world.

Viewfinder

Seeds of a new season

A look ahead

This is the end of today’s Daily issue. On Monday, we’ll have a number of essays linked to America’s Independence Day on July 4, from the patriotism of “interdependence” to the nation’s unique role in the world today. We hope you’ll come back.