- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Coming tomorrow: Biggest Women’s World Cup ever

The ninth Women’s World Cup kicking off Thursday in Australia and New Zealand promises to be the biggest – and perhaps the most competitive – yet.

There are more teams. The field has expanded to 32, with eight teams making their debuts. More countries – such as Morocco, the first Arab nation to compete in a Women’s World Cup – are showing changing attitudes and increased financing in support of the game.

The prize money this year is its biggest yet. FIFA, the organizing body that runs the World Cup, has increased the pot to $152 million for the tournament – an increase of more than 300%.

And there might be more fans. The demand for tickets to Australia’s opening match against Ireland is so high that the host had to move the game to a larger stadium. In recent years, fans of women’s soccer all over the globe have been turning out in record numbers. In 2022, the top three highest-attended soccer matches in Europe were all for women’s games.

But it will take commitment for even die-hard fans in the Western Hemisphere to follow the tournament half a world away. The United States plays its first game against Vietnam in Auckland, New Zealand, on Saturday – that’s 9 p.m. Friday on the East Coast.

All of these factors are combining to elevate the level of competition that has traditionally been lopsided. Remember in 2019 when the U.S. decimated Thailand 13-0 in their opening match? Those days may be limited. Two weeks ago in a warmup game, newcomer Zambia stunned two-time world champion Germany when it won 3-2.

The Americans are seeking a three-peat, after winning in 2015 and 2019. But it’s anybody’s guess who will hoist the trophy this year. And that’s a global win for women’s soccer.

It’s finally everybody’s game.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

On strike: Can Hollywood find a happy ending?

What led to the first double strike of actors and writers in more than 60 years? Both sides point to a business model under severe strain even before the pandemic and a breakdown in trust.

-

Stephen Humphries Staff writer

Tourists hoping to spot A-list actors, ready for their close-ups here on Sunset Boulevard, will be disappointed. Most of the 160,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists are journeyman actors working in video games, audiobooks, commercials – even puppetry.

“We’re not people that are living in mansions ... drinking green smoothies all day,” says Gabriel Rissa, who works in a restaurant to supplement his roles in TV shows such as “Scandal” and “American Auto.” “It’s people that believe so strongly in their art that they’re willing to make sacrifices.”

At a time of upheaval in the entertainment industry, the question of who should make sacrifices is at the core of this double strike – the first time both actors and writers have walked off the job together in 63 years. They point to a vanishing middle-class life, brought on by the shift to streaming models. For their part, studio executives point to cratering revenues that meant they were laying off thousands of employees before the creative talent walked off the job. Both sides are gearing up for a long fight. And the sharp rhetoric reveals a breakdown of trust amid profound industry disruption.

“People are recognizing that this is a historic moment,” says Brian Welk, a senior business reporter for IndieWire.

On strike: Can Hollywood find a happy ending?

Outside Netflix headquarters, the sidewalk is filled with actors and writers marching together in a historic strike. It’s over 90 degrees Fahrenheit. A few palm trees, towering over the street like giant dandelions, offer scant shade. Yet the protesters, holding fans and picket signs, are in good spirits as they chant slogans such as “LA is a union town, on strike, shut it down ...”

Actors put down their scripts and walked off sets last week. That is, off the movies and TV shows that hadn’t already paused production when the Writers Guild of America commenced its strike in May. The unions representing performers and writers have each reached an impasse with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers during their respective contract negotiations.

Tourists hoping to spot A-list actors, ready for their close-ups here on Sunset Boulevard, will be disappointed. Most of the 160,000 members of the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) are journeyman actors working in video games, audiobooks, commercials, corporate or educational videos, and even puppetry.

“We’re not people that are living in mansions, living in luxury, drinking green smoothies all day,” says Gabriel Rissa, who works in a restaurant to supplement his roles in TV shows such as “Scandal” and “American Auto.” “It’s people that believe so strongly in their art that they’re willing to make sacrifices.”

At a time of upheaval in the entertainment industry, the question of who should make sacrifices is at the core of this double strike – the first time both unions have walked off the job together in 63 years. Actors, and before them writers, point to a vanishing middle-class life, brought on by the shift to streaming models that weren’t governed by previous agreements. That erosion of quality of life began before the pandemic, and prior to the recent rapid advances in artificial intelligence. For their part, studio executives at Walt Disney Co. and others point to cratering revenues and stock prices that meant they were laying off thousands of employees before the creative talent walked off the job. Both sides are gearing up for a long fight. And the sharp rhetoric reveals a breakdown of trust amid profound industry disruption.

“People are recognizing that this is a historic moment,” says Brian Welk, a senior business reporter for IndieWire, a film industry site. “It was shocking to me to see just how many actors and writers together were all very much on the same page in terms of their agenda and how unified they were.”

The fallout of the strikes is most acute in Los Angeles and New York, where whole economies of scale are powered by the engine of the entertainment industry. But the shutdown will also be felt across Hollywood’s many regional production hubs, including Georgia, New Mexico, and Louisiana. The impact is also global. Clapper boards fell silent in filming locations such as Morocco and Australia, where “Gladiator 2” and “Mortal Kombat 2,” respectively, had been filming.

Award shows such as the 75th Primetime Emmy Awards in September are at risk of being postponed. Union rules also prohibit actors from promoting movies. On Thursday, the cast of “Oppenheimer” made a show of departing the London premiere when confirmation of the work stoppage came through. During a red carpet interview, actor Matt Damon said that the reason for the strike was “to protect the people who are kind of on the margins,” especially those who rely on health insurance.

Carlease Burke is one of them. With about 170 credits, she’s enjoyed decades of steady acting in movies, commercials, and television shows such as “Dave” and “Mixed-ish.” During pandemic shutdowns, Ms. Burke was able to skate by for two years on her existing income. But three years ago, SAG-AFTRA changed the terms of its health care coverage. In order to qualify, actors must make a minimum of $26,000 from acting each year. That left the actress without insurance for the first time in her career.

As an older person, losing her health care and having to scramble to find an alternative was a blow. “We have really, really good health insurance, and so many people have lost it,” she says.

Some actors rely on residuals – payments received when a movie or television show is seen after its initial run, via reruns, or streaming or on-demand services – to get by or make enough money to qualify for the health insurance. One of the key sticking points in SAG-AFTRA’s negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) is that streaming platforms are unwilling to reveal data that is key to determining those residuals.

“Companies have always tried to monopolize and monetize their own data to their own benefit and to [the detriment of] whoever they’re negotiating with,” says Mitch Lowe, author of the memoir “Watch and Learn: How I Turned Hollywood Upside Down with Netflix, Redbox, and MoviePass – Lessons in Disruption.” “No one is going to be happy until there is some third-party monitoring of the performance or complete transparency.”

Mr. Lowe, a co-founding executive at Netflix, says that archaic contract formulas should be updated to take into account not just subscription revenue but also other value generated by content, including licensing.

Streaming services have also changed the formula for determining residuals. Instead of paying actors a set amount according to how many times a program runs – as the networks do – streamers base their formula on the number of their subscribers. The AMPTP says actors have more opportunities to work because of streaming services, and that actors make money on streaming even if a show or movie flops. But performers say they aren’t getting their fair share when shows hit it big and that residual income has eroded. Since talks broke down, actors from Mandy Moore (“This Is Us”) to the cast of Netflix’s “Orange Is the New Black” have shared their residual checks from Netflix, with amounts ranging from pennies to $20.

In the meantime, metrics for measuring the success of streaming companies have also changed.

“Since early last year, Wall Street has started to get really concerned about the lack of profits in streaming,” says Ben Fritz, author of “The Big Picture: The Fight for the Future of Movies.” “Netflix had an earnings report when their growth was slowing, and Wall Street freaked out.’” Netflix, it should be noted, first reported a profit in 2003 and posted a $4.49 billion profit in 2022. Other direct-to-consumer streaming companies or divisions of larger corporations have yet to make money.

One of the easiest levers to pull to become more profitable is produce less content, says Mr. Fritz, whose Wall Street Journal podcast “With Great Power: The Rise of Superhero Cinema,” chronicles how Marvel came to dominate Hollywood. Indeed, Disney CEO Bob Iger recently announced that the company is cutting back on its multiverse’s worth of superhero offerings. In an increasingly common move, the company also pulled movies and TV shows from Disney+ as content write-offs – including ones released in 2023. And, like many other entertainment companies, it has also laid off thousands of employees.

Actors on the picket lines cite CEO compensation in the tens of millions of dollars as proof the studios have money to pay the people they hire. “How come they’re making so much money?” asks voice actor Hope Levy. “Look, we all want to work together. We’re all open to negotiating, but they need to be open to sharing their corporate wealth that they’re making.”

Economist Donald J. Boudreaux says that view is shortsighted, since employees prosper under adept CEOs, and the ability to run a global corporation is not a common skill.

“It’s worth pointing out the money [Mr. Iger’s] being paid does not belong to those employees. It belongs to the shareholders,” says Mr. Boudreaux, a former economics department chair at George Mason University. “If that person is not very good at doing what he or she does, then that affects the productivity of everyone down the line.”

This week, Moody’s Investors Service predicted that collective bargaining agreements with the unions will collectively cost studios an additional $450 million to $600 million per year.

An executive told Deadline that studios would hold out until the actors lost their homes and apartments – a tactic that didn’t go over well with actors and writers. Those on strike believe that studios don’t truly value them. For instance, a common fear of those on the picket lines outside Netflix is that studios will replace them with AI by scanning their image and likeness, and even their voices, and then utilizing them in perpetuity.

“Obviously we cannot stop technology, but we need to be compensated if they’re going to reuse our voice prints and our voices, or take our voice and then alter it,” says Ms. Levy, who has voiced animated characters in video games and TV movies.

In a statement to the Monitor, the AMPTP claims that SAG-AFTRA leadership has publicly mischaracterized its position on AI and reiterated its position that the deal offered “historic” pay and residual increases. “The current AMPTP proposal only permits a company to use the digital replica of a background actor in the motion picture for which the background actor is employed. Any other use requires the background actor’s consent and bargaining for the use, subject to a minimum payment.”

SAG-AFTRA did not respond to the Monitor’s request for comment.

For now, the unions and the studios are engaged in a public relations battle. Audiences may not notice the disruption in production until September, when bemused viewers notice the most hyped offering on fall TV is ... “The Golden Bachelor.” In the meantime, striking writers and actors keep turning up to march, no matter the temperature.

“Most creatives that I know have been without work for a year” and take on second or third jobs to get by, says Dominique Generaux, whose first movie role was the 2008 film “Dakota Skye.” “So for us, when it’s such an existential crisis, people will go as long as it takes.”

In Congress, Democratic criticism of Israel grows

The sense of shared values that have long underpinned the U.S.-Israel relationship is being called into question on the left, raising concerns about future Democratic support for the Jewish state.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Israeli President Isaac Herzog received a strong bipartisan show of support in Congress today, celebrating 75 years of friendship since Israel’s founding. But the visit also underscored growing tensions within the Democratic Party over Israel, as a handful of progressive lawmakers boycotted the speech, reflecting concerns about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and the lack of progress toward a two-state solution.

In part, the pushback is a reaction to the increasingly right-wing policies of the Israeli government. It also coincides with the growing U.S. movement for social and racial justice, which characterizes the Palestinians as another oppressed minority group.

Democratic defenders of Israel say that seeing the Mideast conflict through the lens of U.S. race relations or South Africa’s apartheid regime oversimplifies the complex history of Israelis and Palestinians, who have engaged in modern-day hostilities going back to the 1930s. But some warn that the rising generation of younger Americans, many of whom lean left politically, holds substantially less sympathetic views toward Israel.

“I’m not worried about Congress. I’m worried about college campuses,” says Democratic Rep. Jake Auchincloss, the great-grandson of Jews who fled pogroms in Ukraine, whose district includes an ideologically diverse Jewish community outside Boston.

In Congress, Democratic criticism of Israel grows

Israeli President Isaac Herzog received a strong bipartisan show of support in Congress today, celebrating 75 years of friendship since Israel’s founding. But the visit also underscored growing tensions within the Democratic Party over Israel, which burst into view again in recent days.

“Today, dear friends, we are provided the opportunity to reaffirm and redefine the future of our relationship,” said Mr. Herzog, a left-leaning scion of Israeli politics now holding the mostly ceremonial position of president. He acknowledged the criticism of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government at home and abroad while emphasizing the deep bonds between Israel and the U.S. A long-time advocate of the two-state solution, he repeatedly voiced support for Israel upholding minority rights, but also took a strong stand against Palestinian terrorism.

“Israel and the United States will inevitably disagree on many matters,” he added. “But we will always remain family.”

A handful of progressive lawmakers boycotted the speech, reflecting growing concerns in the party about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians and the lack of progress toward a two-state solution nearly 30 years after the historic Oslo peace accords laid the groundwork for Palestinian statehood.

Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington, chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, sparked a backlash over the weekend when she assured disruptive “Free Palestine” protesters at a progressive conference that “we have been fighting to make it clear that Israel is a racist state, that the Palestinian people deserve self-determination and autonomy, that the dream of the two-state solution is slipping away from us – that it does not even feel possible.”

She later clarified that her criticism was directed toward current Israeli government policies, and on Tuesday she voted in favor of a House resolution of support for Israel that passed 412-9. But the flap raised concerns that the ironclad bipartisan support Israel has long enjoyed in the United States may be fracturing. A Gallup poll this spring indicated that, for the first time, more Democratic voters now sympathize with the Palestinian cause than with Israel.

The U.S.-Israel alliance, originally grounded in shared religious roots and a commitment to democratic principles, buoyed the nascent Jewish state amid the hostility of its Arab neighbors and gave the U.S. an anchor in a tumultuous region. Though the two states still have strong mutual interests, including opposition to Iran’s nuclear program, the sense of shared values that has long underpinned their relationship is increasingly being called into question on the left.

In part, the pushback is a reaction to the increasingly right-wing policies of the Israeli government, which is looking to overhaul the country’s judicial system and advance policies in the West Bank that undermine – if not preclude – the possibility of an eventual Palestinian state. It also coincides with the growing U.S. movement for social and racial justice, which characterizes the Palestinians as another oppressed minority group to be defended and has raised awareness about their cause through social media.

“One of my values is rooted in human rights of all people, and I strongly believe that if we continue to have a one-sided conversation about Israel-Palestine, then we’ll never get to a place of peace,” says Democratic Rep. Jamaal Bowman of New York, who boycotted the Israeli president’s speech. He says he’s seeing a shift among younger and more progressive Jewish constituents in his district in their attitudes toward Israel, and he challenges more conservative ones to rethink Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

“You fight tooth and nail to ensure there’s not a repeat of the Jewish persecution of the past,” he says. “How can you do that and completely ignore what is happening with Palestinians right now?”

Democratic Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan, the sole Palestinian American in Congress and one of Israel’s strongest critics in the House, also boycotted the speech today. She gave an impassioned floor speech Tuesday calling Israel an “apartheid state” that limits the freedoms of Palestinians like her grandmother.

Democratic defenders of Israel say that seeing the Mideast conflict through the lens of U.S. race relations or South Africa’s apartheid regime oversimplifies the complex history of Israelis and Palestinians, who have engaged in modern-day hostilities going back to the 1930s. At that time, the burgeoning Zionist movement – facing persecution in Europe and urging a return to the Jewish homeland – began to clash with the Arabs who had settled in the area and considered Jerusalem the third-holiest site of their Muslim religion.

But some warn that the rising generation of younger Americans, many of whom lean left politically, holds substantially less sympathetic views toward Israel.

“I’m not worried about Congress. I’m worried about college campuses,” says Democratic Rep. Jake Auchincloss, the great-grandson of Jews who fled pogroms in Ukraine, whose district includes an ideologically diverse Jewish community outside Boston.

For Democratic leaders in Congress, the politics of this split are an unwelcome distraction from their efforts to present a united front against the GOP agenda. House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, both of New York, have been unequivocal in their support for Israel in recent days. Though some Jewish voters may feel increasingly frustrated with fellow Democrats’ increasing sympathy for Palestinians, they still remain a key source of support for the Democratic Party – even as conservative Republicans are increasingly casting themselves as the strongest defenders of the Jewish state. Tuesday’s resolution, brought by House GOP leaders, was widely seen as an attempt to highlight and exploit that Democratic divide for political purposes.

A number of progressive lawmakers declined requests to comment on intraparty tensions over the U.S.-Israel relationship. And the fact that only 2% of Congress voted against the pro-Israel resolution underscored how important the relationship between Israel and America, which President Herzog repeatedly referred to as “our greatest friend,” continues to be for both parties.

Still, Rep. Brad Sherman, an Ohio Democrat who has been on the House Foreign Affairs Committee for more than a quarter-century and is descended from Russian Jews, says the vote would have been different among rank-and-file Democrats – and that could be an issue going forward for Israel.

“Israel has one friend in the world, plus Guatemala, and cannot afford to have only one half of one friend in the world,” he says.

In Israel, Ms. Jayapal’s comments got little play, but President Joe Biden’s relationship with Prime Minister Netanyahu – whom Mr. Biden on Monday invited to come to the U.S. later this year – featured prominently on news sites this morning.

New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman wrote Tuesday that in the same phone call, President Biden also warned his Israeli counterpart that he needed to slow down and secure consensus for his government’s judicial reforms – or risk losing America’s support. The reforms, which would readjust the balance of power between Israel’s left-leaning Supreme Court and its right-wing government, have sparked massive protests – including by military reservists whose ongoing service Israel depends on for its national security.

It’s a delicate balancing act for Mr. Biden, whom Mr. Friedman characterized as potentially “the last pro-Israel Democratic president.” He is trying to respond to an increasingly influential progressive wing of his party, while still maintaining a strong U.S.-Israel alliance based on shared democratic values.

“Israel has held a larger-than-life hold on the American imagination not because of sharing intelligence information or even sharing military cooperation, but it’s because they’ve been seen as a country committed to a Western sense of shared values,” says David Makovsky, former senior adviser on Israeli-Palestinian negotiations at the State Department and a fellow at The Washington Institute. “You don’t give up on that easily.”

The Explainer

First challenge in Guatemalan elections: Getting to run

Guatemala’s fragile democracy is on a knife-edge, as a prosecutor of dubious impartiality challenges a surprise reformist presidential candidate’s legitimacy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Guatemala’s presidential elections are in turmoil. The vote last month – seen as key to the country’s fragile democracy – upset all predictions and sent Bernardo Arévalo, a liberal reformist, through to the second round. Then, a court suspended his party, accusing it of fraud.

The ruling has galvanized a disillusioned electorate, propelling Guatemalans onto the streets in protest. The electoral tribunal has refused to abide by the court’s ruling, and even Mr. Arévalo’s rival has suspended her campaign in solidarity with him.

“Anything can happen between now and the runoff” next month, says Byron Morales Dardón, a local political analyst. He sees the court order as a bid by powerful business people and politicians to block any chance of reform of a system that’s good for the elite – but notorious for corruption.

Guatemala was once at the forefront of Latin American efforts to combat corruption, but when a widely admired independent anti-corruption commission began implicating business, military, and political elites, its mandate was allowed to expire.

Now, says Mr. Morales, “what happens next will really depend on social mobilization. Citizens have to show they won’t stand for” meddling in the democratic process.

First challenge in Guatemalan elections: Getting to run

In the first round of Guatemala’s presidential election on June 25, a relatively unknown anti-corruption candidate won enough votes to go through to the runoff.

Bernardo Arévalo’s advancement was a huge surprise – but that paled in comparison with what came next.

The same day that the first-round results were certified, a criminal court suspended Mr. Arévalo’s political party, Movimiento Semilla, throwing his candidacy into question and the nation into political crisis. The move galvanized a disillusioned population (null ballots had outstripped all the candidates in the first round), propelling Guatemalans onto the streets in protest.

What’s going on?

This presidential election has further weakened Guatemala’s already fragile democracy. In the lead-up to the vote, several candidates seen as threats to the business and political establishment were disqualified, on shaky grounds, from running.

Mr. Arévalo, an academic and former diplomat, defied the polls by winning 11.8% of the ballots, coming in second behind former first lady Sandra Torres. He is the son of Juan José Arévalo, the country’s first democratically elected president, who took office in 1945, following the Guatemalan revolution. Many expect that if he won, he would continue his father’s legacy of investing in social programs, but critics paint him as an extreme leftist and loudly protested his advancement.

The prosecutor who brought the case against Mr. Arévalo’s party, accusing it of fraud in gathering the signatures required for its foundation in 2019, is under U.S. government sanctions for having allegedly blocked corruption investigations in the past. The prosecutor’s new move is widely seen as politically motivated.

The electoral tribunal, however, refused to comply with the criminal court’s order to suspend a political party active in an election. “If there is no respect for the vote, there is no democracy,” the tribunal said on July 13. Mr. Arévalo said he would not obey the order, and his rival, Ms. Torres, suspended her campaign in solidarity.

The Guatemalan prosecutor’s office later said it would continue to investigate how the anti-corruption party was registered, but that its actions were not intended to interfere with the runoff scheduled for Aug. 20.

“Anything can happen between now and the runoff,” says Byron Morales Dardón, a political analyst and researcher at Rafael Landívar University in Guatemala City. Those in power “are interested in stopping any possibility of real change. What happens next will really depend on social mobilization. Citizens have to show they won’t stand for” meddling in the democratic process.

How did Guatemala get here?

A lack of judicial independence has been at the heart of Guatemala’s recent turmoil. While lower court judges go through rigorous selection processes, those on some of the highest courts are essentially political appointees, some hand-picked every five years. “There is a system set up that favors impunity and corruption,” says Claudia Escobar, a legal scholar and visiting professor at George Mason University, where she co-directs a fellowship program for democracy defenders and anti-corruption activists.

“We don’t have a Daniel Ortega or Maduro,” she says, referring to Nicaraguan and Venezuelan autocratic leaders. “What we have is a dictatorship of corruption.”

But isn’t Guatemala known for its dedicated fight against corruption?

Yes – kind of! A United Nations-backed anti-corruption commission known as CICIG, founded in 2006, became the envy of many regional neighbors struggling with impunity and serious crime. But some felt CICIG went beyond its mandate, and when investigations started implicating economic, military, and political elites, the program was not renewed. It expired in 2019.

Four years earlier, Guatemalans had risen up in outrage over political corruption, leading to the ouster of then-President Otto Pérez Molina. “What happened in that case – and it can happen again – was that there wasn’t any structural change,” says Ms. Escobar, a former judge who sought protection in the United States after reporting official interference in the judiciary. “The president resigned, there were fresh elections, and [a new president] started his term with an intention to reform the constitution,” she recalls.

“Everyone knew the constitution needed to be reformed for the judicial system to work,” she adds, but Congress looked away.

Guatemala cannot afford another missed opportunity, democracy analysts warn. Voter turnout was not especially high this year, Mr. Morales says, but citizens seemed to wake up when the first-round election results were announced. “It stimulated a series of reactions. An unexpected player in the runoff offered the possibility of a new moment for the country. It generated some optimism,” he says.

But the move to disqualify Movimiento Semilla – and the implication that Mr. Arévalo could be barred from running – “generated a new level of indignation around the manipulation of the law,” Mr. Morales says. “It’s anger over what looks like the sacrifice of a nation’s democracy for personal gain.”

What’s at risk?

Guatemala is a major source of migrants to the U.S. Political instability and knock-on effects such as a lack of access to public services are root causes of migration.

Regionally, there has been a shift toward authoritarianism: Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega has exiled his loudest opponents, while in El Salvador, President Nayib Bukele’s supporters have overridden a constitutional ban, enabling him to run for reelection.

Already, Ms. Escobar feels, Guatemala has taken note of events in places like Nicaragua, where she says the message has been “if you’re in power, whatever you do, don’t lose control.”

Mr. Morales agrees. “This is a political dispute that could determine where the country goes in the long term,” he says. It could reaffirm “the enormous political and economic powers that seek ... continuation of the old order of inequality and social injustice,” he says, or it could “possibly reactivate Guatemala’s process of democratization.

“That’s the big question – everything is in play.”

A deeper look

Fighting wildfires – a family tradition

Excitement is a big draw for wildland firefighters, but a commitment to each other – and, in some cases, to their families – keeps them battling fires.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 13 Min. )

-

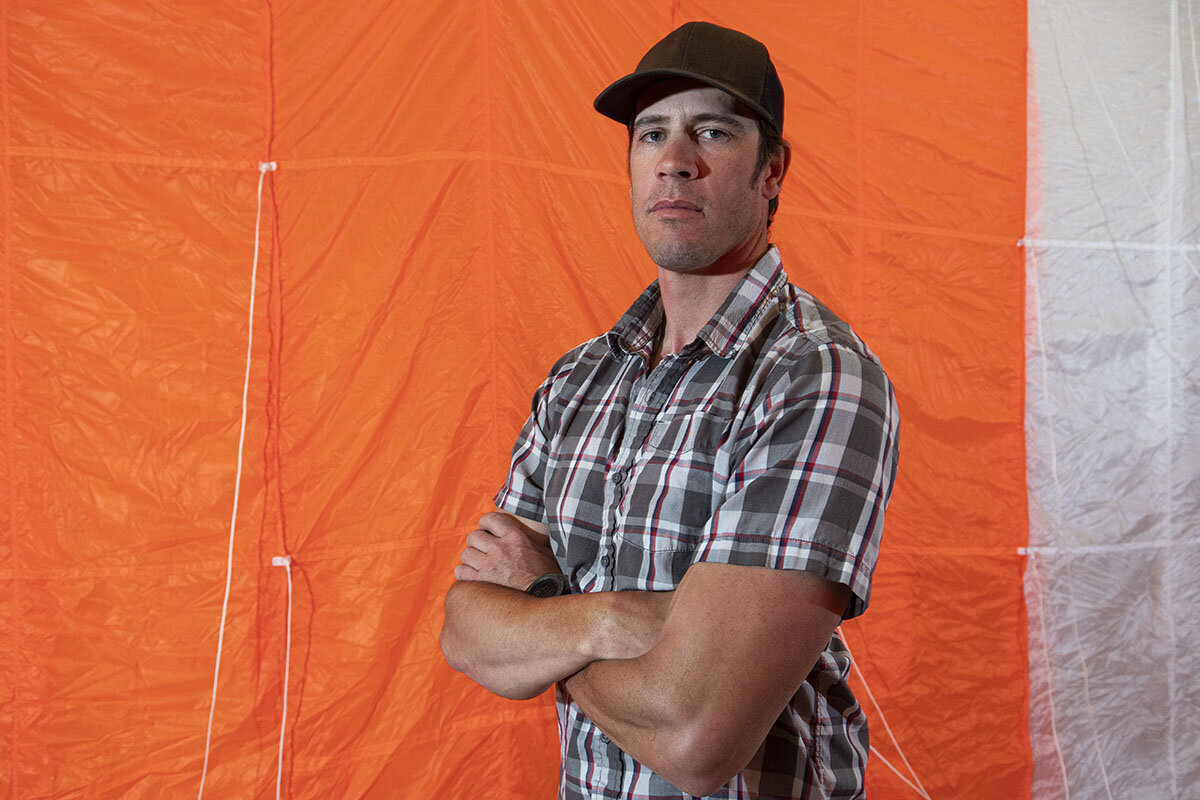

By Doug Struck Special contributor

-

Alfredo Sosa Staff photographer

Thousands of paid and volunteer firefighters will leave their homes this summer to combat the wildfires erupting with growing ferocity in a drier, hotter climate. That rough army is often knit by a web of family ties. It is a network formed of tradition, pride, and shared family values.

For Joe Brinkley, it started when he and his three brothers were working summer jobs at a factory in 1990 and a wildfire spread near town. “They asked people at the mill if you guys want to put a crew together and work this fire. We all said, ‘OK, whatever,’” recalls Mr. Brinkley. “And three out of the four of us decided that, yeah, that’s what we want to do.”

Despite one of his brothers being killed in a fire, Mr. Brinkley says it was the right career for him. Now retired after 30 years, he has no regrets: “Being able to spend time in the woods is where I want to be,” he says.

Sheri Nickel has been a firefighter for 22 years. She serves with her husband, Darrin, in the Orlando Volunteer Fire Department in Oklahoma. Their two children “grew up with us leaving birthday parties,” Ms. Nickel says. “We’ve had fires on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day and Thanksgiving. They just always understood that if we don’t do it, then nobody’s going to do it.”

Their son and daughter, now grown, are firefighters, too.

Fighting wildfires – a family tradition

Joe Brinkley was at a crossroads in life. He loved fighting fires in the wild – the camaraderie, the intense work, the long days in remote forests. But he had quit and started working at a tire store in Boise for better pay and steady work. He didn’t like it much, but he wasn’t sure he could afford to go back to firefighting to join two of his brothers.

Then, the worst. A wildland crew faced a blaze sparked by lightning near Glenwood Springs, Colorado. A passing cold front sent the flames roaring through South Canyon, overtaking and killing 14 of the firefighters on July 6, 1994. Levi Brinkley, Joe’s triplet brother, was among them. Joe Brinkley was stirred by the firefighters and townspeople who descended on his parents’ home in Oregon to help mourn the loss.

“That’s when everything changed for me. I decided this is what I truly need to do with my life,” Mr. Brinkley recalls. His brother’s sacrifice helped show the way: “I probably wouldn’t have had enough courage to make that decision” otherwise, he adds.

Thousands of paid and volunteer firefighters will leave their homes this summer to combat the wildfires erupting with growing ferocity in a drier, hotter climate. That rough army is often knit by a web of family ties: father and son, mother and daughter, brothers, sisters, cousins. It is a network formed of tradition, pride, and shared family values.

“It’s about DNA. It gets in your blood,” says Steve Hirsch, a lawyer and volunteer firefighter in northwest Kansas. His father started a local fire district in 1963 to help fight prairie fires. “Been around this my entire life,” says Mr. Hirsch. “Had brothers involved and Father and all sorts of nieces and nephews and all that. So I don’t know anything any different.” Firefighting, he says, runs through families.

For Joe Brinkley, it started during a summer job in a laminate factory. Four Brinkley brothers, all from a ranching family in eastern Oregon, were working there in 1990 when a wildfire spread near town. “They asked people at the mill if you guys want to put a crew together and work this fire. We all said, ‘OK, whatever,’” recalls Mr. Brinkley. “We got to be out in the woods and see deer or elk or wildlife. And three out of the four of us decided that, yeah, that’s what we want to do.”

After Levi’s death, Mr. Brinkley spent three decades as a firefighter before retiring 18 months ago as a smokejumper and base manager in McCall. He still is on the list to help with fires when needed. His older brother Josh works for the Forest Service at Sawtooth National Forest in Idaho.

“It was the right decision,” Mr. Brinkley says. He met his wife, Alexis, who works for the Forest Service, on a Hotshot fire line in 1996. “We are still walking and talking and escaped with very minor injuries,” says Mr. Brinkley. By “very minor” he means six shattered teeth, a broken spine, six fused vertebrae, a separated rib cage, four broken ribs, and emergency resuscitation when a tree fell on him.

He has no regrets: “Being able to spend time in the woods is where I want to be,” he says.

Federal firefighting crews are the main bulwark at the largest of fires. An estimated 11,300 men and women will be shuffled in and out of fire lines this summer by a federal control center in Boise. Thousands more in local fire departments – often staffed entirely by volunteers in rural areas – will join the fight. They are regularly the first on a scene when lightning, a campfire, or a downed power line ignites dry, brown vegetation.

The National Interagency Fire Center counted 68,988 wildfires in the United States last year.

In interviews, firefighters say they are drawn to the rugged challenge, feed on the adrenaline, and revel in hard work with trusted companions. They like the public service of their work. Many saw their parents do the same. That family imprinting is a pipeline for the firefighting corps.

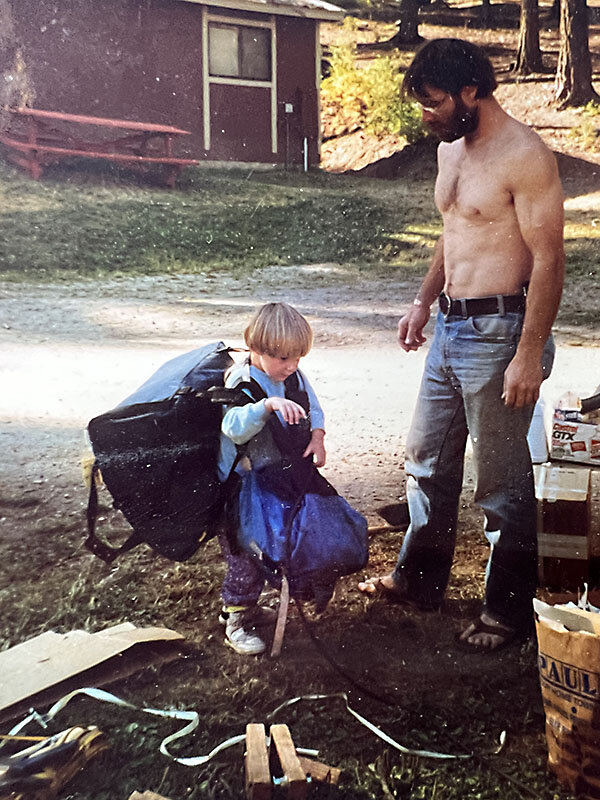

“Everybody said I was brainwashed,” says Damian Withen. His father was a sociology professor at the University of Virginia’s College at Wise for 18 years, but every summer the family returned to McCall so he could work as a contract smokejumper, parachuting onto fire lines in wilderness areas throughout the country. Damian played at the base, wore a miniature smokejumper’s suit, and practiced parachuting runs with a buddy in a doghouse-turned-imaginary-airplane.

“Do not jump off the roof,” his parents warned sternly.

His father, Patrick Withen, fought fires in summers over nearly five decades. He got into smokejumping while working on a ground crew in Montana. One time, they hiked all day up a rugged mountain, only to find smokejumpers had gotten there hours earlier, had contained the fire, and were sitting having coffee. “It just seemed to be the way to do it,” Dr. Withen says.

Damian joined a fire crew just out of high school in 2006, worked on ground crews in Idaho and Montana, and became a smokejumper in 2013, eventually moving to McCall.

“I thought it was a good thing that he wanted to be a smokejumper,” says Dr. Withen, who now lives with his wife, Diana, across from their son at the edge of woods in McCall. “It’s not about the money, but it’s a great, rewarding career.”

The allure of this work has cracks, though. Federal firefighters may work two-to-three-week contractual assignments at wages that ranged widely in the past but finally were recently leveled up to at least $15 an hour. Contract work can go on for years before one is hired in a permanent position at a base salary starting around $35,000. A Biden administration bonus following the pandemic is set to expire unless Congress acts by Sept. 30. Firefighters say their ranks are being drained due to low pay and long stretches away from their families.

Paul Acosta tries to bolster the firefighting tradition. He teaches firefighting to middle and high school students in Brush, Colorado, a town of 5,300. When his students graduate, they are qualified to sign on to a wildland firefighting team.

Mr. Acosta has been with the Brush Volunteer Fire Department for 30 years. Especially in the open West, firefighters spend more time fighting wildland fires than answering calls in town. In Mr. Acosta’s area, wildfires may roar across the grassland prairies in towering waves of flame, threatening crops, farmhouses, livestock, and people.

“We are losing volunteer firefighters very quickly,” says Mr. Acosta, a vice chair of the National Volunteer Fire Council. “A lot of people just don’t have the time.” Or the option. “When I started, you would drop everything you were doing to go on a fire call,” with the principal of his school taking over his classes, he says. Now, many people work far from small towns like his, and employers are not so accommodating.

And there is the danger. Federal agencies report that 25 wildland firefighters died last year. Most did not succumb to smoke or flames, but to associated risks: vehicle accidents on smoky back roads, helicopter crashes, heart attacks in the heat, trees falling unexpectedly on ground crews. But the chief fear of firefighters is a “burnover,” when winds and flames dramatically reverse direction, engulfing firefighters.

As the smoke and dust rose from the collapsed World Trade Center towers Sept. 11, 2001, April Partridge grabbed her firefighter gear in southern New Mexico and declared that she was headed to New York to help with the grim search of debris. Her son Bryan Wilken was 8. He sat in the doorway and refused to let her go.

“I told my mom, ‘You’re not going because I don’t want to lose my mom,’” Mr. Wilken recalls.

It was, he says, one of the few times he won the argument. But it was eerily prescient of the way firefighting would play out in the lives of the mother and son. Ms. Partridge loved the work and helped at fire departments as she moved around the country for the Defense Department. As he got older, Mr. Wilken joined the local department where they lived in Apache, southwest Oklahoma, before moving to Michigan.

In 2021, Mr. Wilken returned to Apache, which the family considered home. His mother, then living in North Carolina, followed him. They both joined the local Edgewater Park Volunteer Fire Department. “She wanted to get on a truck and fight fires next to her son,” Mr. Wilken says. “That’s always been one of my dreams, for me and my mom to be on the same volunteer department.”

A few weeks after she joined, a field of dry 6-foot-tall prairie grass south of Apache erupted in flames on March 20, 2022. It began racing toward a cluster of homes.

“It was a fast, aggressive fire. It was running across the tops of the grass. ... I would think it was moving 30 to 40 feet a second,” Mr. Wilken recalls. It “was definitely something I’ve not seen before.”

He drove in his pickup truck toward the closest houses, urging people to flee to safety. His mother raced to the fire station and jumped aboard a brush truck with the fire chief to confront the flames.

But the fire was not to be tamed.

Mr. Wilken was still in the housing development when his radio erupted. “Firefighter down!” He raced to the other side of the fire. A close friend in the department met his truck and refused to let him get out. “Your mom is gone. You do not need to see this,” the friend told him. She had been caught by a burnover when she was outside the truck.

The fire lasted two more days.

The funeral for Ms. Partridge was huge – the procession of first responders stretched 3 miles, and the Highway Patrol closed down Interstate 44 for the somber occasion. Children from a local day care waited at the cemetery wearing plastic fire hats.

More than two months later, the small Edgewater Park Volunteer Fire Department reopened for calls. Mr. Wilken was there, and soon he assumed the role of fire chief. He said there was no doubt he would return.

“My decision was, I’m not going to let this defeat me. My mom would not want me to give up on something I love to do.”

For others, too, the dangers do not overcome the calling – and the community that comes with it.

Kevin Quinn had some moments in 48 years of firefighting. He recalls a wind shift on a wildfire in the Nez Perce national forest in Idaho. The sky turned orange, the flames licked toward them on the ridge, and his crew started running madly for their lives. As he huffed along, the local Nez Perce crew raced past him. Suddenly, a fire copter above radioed down that they were running right toward the fire and to reverse immediately.

“I went from being last to first,” recalls Mr. Quinn. He laughs about it now, but the situation still haunts him 26 years later.

When his son Joshua graduated from high school in Rhode Island and wondered what to do, he asked his dad about firefighting. Before long, Joshua signed up to fight wildfires in the West, eventually joined a “helitack” crew to rappel from helicopters onto fire lines, and recently moved to Florida to a U.S. Forest Service fire team at the Ocala National Forest.

His first federal dispatch was to the stunning Glacier National Park in Montana. He was hooked. Having winters off to go snowboarding was a plus, too.

Mr. Quinn’s girlfriend from Rhode Island, Erin Noblet, says she knew nothing about wildfires “other than Smokey the Bear.” Soon after she joined him in Utah, 19 firefighters were killed when overrun by a wildfire in Arizona, which shook her and much of the firefighter community.

They married and now have two young children. Mr. Quinn squirms at the question of whether he would want them to be firefighters. Not his wife.

“Ironically, yes,” she replies right away. “I mean, it’s like family away from family. There’s definitely a feeling of support.”

The alarm squawks over the loudspeaker at the McCall Smokejumper Base. A team of seven men and one woman races to the “jump rack,” where their suits are hanging, ready. They have two minutes to dress. Weighed down by 100 pounds of parachutes, gear, and padding stuffed into special pockets of their jumpsuits, they waddle out to the De Havilland Twin Otter plane and head to bolster a crew fighting fires in California.

The other jumpers cheer them on, exchanging high-fives as Willie Nelson’s “On the Road Again” blares from the speakers.

“People tell us, ‘I hope you don’t have to jump many fires this summer,’” muses Mr. Withen, who grew up spending summers playing at the base. “They don’t understand. This is the reason we do it. That’s everybody’s favorite part.”

Besides, adds another firefighter as he watches the team depart, “this is when we get paid.”

Many seasonal firefighters are paid only when they are on a fire. Others, including most smokejumpers, are paid for six months a year. But only when they are on a fire, earning hazard pay and working long hours of overtime, do their incomes start to grow. A slow fire season means low pay.

“We talk about money all the time, but a lot of us didn’t get into fire for money,” says Garrett Hudson, who followed his father into firefighting in 2002 and eventually smokejumping. But when his father was a firefighter, “you could afford a house. You could still afford to live fairly well,” he notes. “But in the last seven to eight years, the pay hasn’t gone anywhere, and the cost of everything else has gone up so high.”

“There’s a lot of other jobs where you can work less and get paid more,” acknowledges Brent Sawyer, the operations foreman at the base. Applications and retention are down. But he notes, “I work with the best people you could ever imagine. And we get to see some amazing country.”

It is the ultimate brother’s compliment: “He’s a good dude,” says Jake Fischer of his brother Isaiah. That may help explain why three Fischer brothers followed similar paths from their parents’ cattle ranch in rural Oregon into firefighting.

Jake and Isaiah are federal smokejumpers in Alaska, Ed Fischer fights fires from helicopters and engines in Oregon, and a fourth brother worked in a fire training crew for a year. There was one photo, Jake recalls, when he, Isaiah, and Ed all worked on a fire in California in 2020.

“All three of us were together,” Jake says by phone from Fairbanks the day before he flies to help firefighting crews in Canada. “That was really neat. I was working for my older brother, and my younger brother was working for me.”

Did it bring any fraternal friction? “Oh, I mean, how does it not?” Jake says with a laugh. “You spend 14 days at 16 hours a day glued together. And then you have your older brother, who ‘knows all,’ telling you what to do?”

The photo of the three of them on that fire “was one of those times where you take one picture, and that’s ‘the snapshot’ that could be for your life.”

Isaiah, the oldest, was the first to join a fire crew. He loves it, he says: “Being way out in remote Alaska, we travel to places you don’t get to go as a member of the public. The adventure, wildlife, and living outdoors. The camaraderie – everybody working together.”

Isaiah says Jake followed him to Alaska. Jake, eight years younger, frames it differently: “He kept pestering me to come up there.”

Sheri Nickel has been a firefighter for 22 years. She serves with her husband, Darrin, in the Orlando Volunteer Fire Department in Oklahoma. Their two children “grew up with us leaving birthday parties,” Ms. Nickel says. “We’ve had fires on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day and Thanksgiving. They just always understood that if we don’t do it, then nobody’s going to do it.”

One of their children, Samantha McCandless, is now married, with two young children of her own. Seven years ago, she stopped at the Shattuck Fire Department, about 150 miles from Orlando, and joined. Having watched her parents, she says it was inevitable. “I was like, ‘I guess, you know, it’s my turn.’”

Editor’s note: To learn more about the McCall Smokejumper Base, including how rookies are trained, explore Alfredo Sosa’s photo essay.

In Pictures

The smokejumpers of McCall, Idaho

It takes courage, training, and teamwork to make it as a smokejumper. Rookies become adept at reading the weather, rigging gear, and landing softly.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

Smokejumpers are a special breed of firefighter. In addition to being physically fit, they must learn how to read the weather and jump safely out of planes into scorching wildfires.

On a recent morning at McCall Smokejumper Base in Idaho, the team gathers for the daily weather report. This is not your typical TV news fare. With charts and graphs, the report goes in-depth on wind speed, humidity, pressure, conditions on the ground, and an array of other data.

Then the smokejumpers pile into two planes to practice their skills parachuting into a meadow. Each team has a spotter who determines the release point from the plane. Later, when the crews are back on the ground, the jumps will be rated for accuracy and, more importantly, soft landings. No fire jumper wants to be injured on the drop into a conflagration.

Smokejumpers have to be ready at a moment’s notice for dangerous assignments in far-flung locations. For newbies, the training is rigorous and taxing.

When asked why rookies are pushed so hard, operations foreman Brent Sawyer smiles and says, “We just want to make sure they want to be here.”

The smokejumpers of McCall, Idaho

As a new morning starts, the McCall Smokejumper Base in Idaho is already in full swing. Rookies are being put through the wringer, doing pushups and pullups to the tune of trainers shouting, “What do you want to be?” When I ask operations foreman Brent Sawyer why rookies are pushed so hard, he smiles and says, “We just want to make sure they want to be here.”

At the same time, the operations desk gathers the rest of the smokejumpers for the morning weather report. This is not your typical TV news fare. With charts and graphs, the report goes in-depth on wind speed, humidity, pressure, conditions on the ground, and an array of other data that I can’t follow. As the smokejumpers listen, I almost see a spark of hope in their eyes for the opportunity to jump a fire. If I were to describe the typical smokejumper, I would say he or she is a combination of a special ops soldier, a tailor, and a ski bum.

This morning, smokejumpers pile into two planes to practice their skills by jumping into the meadow below, where the landing spot is marked with a small flag. Each team has a spotter who determines the release point from the plane. Later, when the crews are back on the ground, the jumps will be rated for accuracy and, more importantly, soft landings. No fire jumper wants to be injured on the drop into a conflagration.

Back at the base, there is no idle moment. All the parachutes that have been deployed must be meticulously inspected for rips and defects, and every single line must be checked individually. From this point, the chute goes either to the repair shop or to be rigged. The art of rigging, which demands full-body action and intricate folding, is a combination of sumo wrestling and origami-making. This goes on for hours.

At the end of a long day, the sun starts to hide behind the snowcapped mountains.

I drive off the base and see a small group of runners on the side of the road. One of them sings out, “What do you want to be?” and the rest reply, “Smokejumpers!”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Honest governance finds a footing in Latin America

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A year ago, Panama was caught in its worst social crisis in decades, stoked by widespread discontent over rising costs and unemployment. Now the slender country bridging the Americas may be recharging its currencies of trust. A court in Panama yesterday sentenced former President Ricardo Martinelli to more than 10 years in prison for money laundering. The penalty has significant ramifications in a country striving to end a long history of corruption.

The court’s decision marks a rare moment of judicial independence and reinforces legal reforms helping to change the country’s reputation as an international haven for graft. At a time when most Latin American countries have lost ground in global measurements of democracy, Panama has continued a three-year run of progress countering corruption.

Honest governance finds a footing in Latin America

A year ago, Panama was caught in its worst social crisis in decades, stoked by widespread discontent over rising costs and unemployment. People felt “deeply offended and humiliated,” one diplomat noted, by “corruption and a lack of empathy [from politicians] during these difficult times.”

Now the slender country bridging the Americas may be recharging its currencies of trust. A court in Panama yesterday sentenced former President Ricardo Martinelli to more than 10 years in prison for money laundering. The penalty has significant ramifications in a country striving to end a long history of corruption. Just last month, Mr. Martinelli won the nod to lead his party into next year’s elections. If the sentence is upheld on appeal, he will be barred from running.

The court’s decision marks a rare moment of judicial independence and reinforces legal reforms helping to change the country’s reputation as an international haven for graft. At a time when most Latin American countries have lost ground in global measurements of democracy, Panama has continued a three-year run of progress countering corruption.

The country was the most improved in the latest annual Capacity to Combat Corruption Index, published last month by Americas Society/Council of the Americas. The Financial Action Task Force, a global watchdog on money laundering and terrorism finance, has meanwhile indicated that it may soon remove Panama from its list of countries requiring “increased monitoring.”

Reforms tell part of the story. The country has adopted new rules of reporting for senior government officials to identify potential conflicts of interest. It has also boosted its cooperation with international partners like the United States in countering narcotics trafficking and money laundering.

But its real gains may be in softer shifts. Following the unrest last year, President Laurentino Cortizo established a citizens commission on corruption to empower public reporting of graft. Since his election in 2019, he has also quietly shifted the gender balance in the judiciary, nominating women to six vacancies (out of nine seats total) on the Supreme Court. Under a new system, judges are chosen by merit. A study by the World Justice Project showed that the judiciary, long sullied by corruption, is now the most trusted public institution.

Mr. Cortizo, who is barred by the constitution from seeking reelection next year to a consecutive term, has – by his count – launched 624 community development projects during his term. The projects include building schools and health care centers, investing in local agriculture, and seeding small businesses. These may not have an explicit purpose of combating corruption. Yet they are strengthening civic bonds. While only 25% of Panamanians report having a lot of trust in national public officials, the World Justice Project survey found 51% expressed a lot of trust in their fellow citizens.

“Our challenge is to make a prosperous country based on law and order, but – above all – fair,” the president promised in his inaugural address.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A great defense

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Raffles

Putting on the mental armor of Godlike thoughts doesn’t just bring us confidence in precarious situations – it reveals to us God’s palpable, ever-present protection.

A great defense

What should we rely on for protection?

In biblical days, some people came to rely on a higher, surer, stronger power than great walls to ensure safety from enemies and the elements: God. Describing such trust in God, the psalmist wrote, “He only is my rock and my salvation: he is my defence; I shall not be moved” (Psalms 62:6).

Later on, in encouraging us to find our strength and power in God, the Apostle Paul likened certain qualities of thought to pieces of body armor. He urged the Ephesians to “put on the whole armour of God.... having on the breastplate of righteousness ... taking the shield of faith.... And take the helmet of salvation, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God” (Ephesians 6:11, 14, 16, 17).

Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science, similarly wrote, “Good thoughts are an impervious armor; clad therewith you are completely shielded from the attacks of error of every sort. And not only yourselves are safe, but all whom your thoughts rest upon are thereby benefited” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 210). Consciously holding righteousness, faith, and salvation in our thought confidently places our trust and reliance on God. We can know Him as ever present and all-powerful, watching over us every second, and nothing can penetrate the divine armor He provides.

God’s protecting power was distinctly demonstrated to me in a life-threatening experience some years ago. I was in the far-right lane of a four-lane highway, traveling 60 miles per hour, with the cab of a large semitruck on my left. Suddenly, a car from the far-left lane veered in front of the truck, and the semi moved into my lane, its huge front wheel grinding into my door.

At that moment, I had time for one thought only – that God is my protection against all forms of harm, that His allness provides an impenetrable defense. As His beloved spiritual offspring, I could never for an instant be separated from His love and care. In the fleeting seconds of that experience, I felt His protecting hand on me.

The front of the truck slammed into the rear of the car that had cut in front, spinning the car off the road to the right. The truck then flipped on its side away from me and slid several hundred feet. I struggled to regain control of my car and ended up sideways across the highway. All the cars behind us were able to come to a stop without broadsiding my car, despite the 60-mph speed limit.

God’s protection was so all-encompassing that no driver was seriously hurt, and my car actually remained drivable! The state trooper looked at the large round tire marks on my door (mere inches from where I had been sitting) and said it was a miracle that no one was seriously injured.

What was it that meant so much to me in that moment of need? It was a sense that God’s power was a palpable and irresistible force present right at that moment. A sense that God lovingly wraps each one of us in His great love and care. A sense that God’s power and presence conquer the dangers that seem to confront us.

We can maintain a strong defense against anything ungodlike by learning about our inseparable oneness with God and mentally affirming the spiritual facts of being throughout each day. We are never truly outside of God’s protection, vulnerable to physical or mental harm. And His defense is perfect, impregnable against all forms of evil.

Viewfinder

Dessert in the desert

A look ahead

We’re glad you joined us today. Please come back tomorrow, when columnist Ned Temko examines why the far right may see a breakthrough moment in Europe, with an upcoming vote in Spain pointing to a trend in a number of European states.