- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A Namibian truck finds its purpose

When we pulled out of the Namibian capital of Windhoek in an oversize pickup on an assignment, photographer Melanie and I met endless stretches of remote highway – and countless Namibians seeking a ride. Despite our abundance of space, we agreed we wouldn’t pick up anyone, even though we hated that choice.

Then came Claudia, Jennita, Uetuu, and Mbakondja. As we were filling up our tank ready to leave the remote town of Palmwag, a man approached us with a question: Could we take his children? The man turned out to be their uncle, and the children were trying to return to their school about 30 miles away after holiday break.

Mel and I looked at each other and nodded. The four threw blankets and pillows, backpacks, and duffel bags into the truck bed. It was only then, as they piled into the back seat, that I recognized them. I had been wandering around Palmwag the night before when they smiled at me from their one-room home. I had introduced myself and asked about school. They told me it took the whole day to walk.

Maybe that’s why their uncle approached us. Or maybe he just sensed he could trust two women with lots of extra space.

The kids chatted excitedly in their native Otjiherero and blew bubble gum. They politely answered questions in English about their favorite classes, foods, animals, and after-school sports. Two want to be doctors; another a lawyer; and little Uetuu, age 7, a police officer.

When we arrived, their friends ran up to hug them and helped them carry their bags across the dusty schoolyard to the rooms lined with bunk beds, where they’ll board for months at a time. As we waved goodbye, Mel and I looked at each other again and smiled – sad that kids like our four friends routinely face daylong treks to school, but glad our massive vehicle finally found its noble purpose.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Struggles over diversity initiatives strike corporate world

Hiring based on race or ethnicity was already illegal before last month. But a court ruling on affirmative action is roiling boardrooms – even as their focus on diversity isn’t likely to disappear.

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down affirmative action at colleges and universities, conservatives are turning their fire on corporations. The struggle over companies’ diversity efforts has already begun.

For example, Republican attorneys general in 13 states sent a letter warning America’s largest corporations of “serious legal consequences” for their initiatives on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The conservative argument is that efforts to hit diversity targets for things like hiring are unconstitutional as a race-based preferential treatment.

On Friday, the president of Texas A&M University resigned because the hiring of a high-profile journalism professor came under fire for her past work on diversity.

Activists on both sides of the issue expect the fallout to spread. Still, even though the ground may be shifting, that doesn’t mean corporate diversity efforts will disappear.

“In this day and age in the 21st century, you can’t just say, ‘You know what, we're kind of done with that DEI thing,’” says Ishan Bhabha of the law firm Jenner & Block. The advantages of being able to draw from a greater talent pool and to address an increasingly diverse customer base make diversity a corporate imperative, he says.

Struggles over diversity initiatives strike corporate world

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down affirmative action at colleges and universities, conservatives are turning their fire on corporations. The struggle over companies’ diversity efforts has already begun.

Following the June 29 decision, the House of Representatives passed a defense policy bill with several social policy amendments tacked on, including the elimination of the Pentagon’s programs for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Republican attorneys general in 13 states sent a letter warning America’s largest corporations of “serious legal consequences” for their DEI initiatives. And on Friday, the president of Texas A&M University resigned because the hiring of a high-profile journalism professor came under fire for her past work on diversity.

Activists on both sides of the issue expect the fallout to spread. “It’s already happened in higher ed. It’s going to happen in the corporate space,” says Sy Stokes, vice president of research at Coqual, a New York think tank on DEI.

At issue: how best to promote fairness in a society that enshrines equality but whose economic realities continue to fall short of that ideal.

“The fundamental problem is, when you cut through all the rhetoric, ... the idea of individual equality under the law as opposed to equity,” says Reed Rubinstein, director of oversight and investigations for America First Legal, a conservative nonprofit legal foundation challenging preferential hiring and other corporate diversity efforts. Conservatives support the idea of equality, meaning that everyone is treated equally under the law.

Proponents of DEI say that’s not enough. “Equity means actually doing things to correct the historical imbalance of racial justice or gender justice that we’ve seen,” says Dr. Stokes. “It won’t be corrected unless there are targeted efforts toward improving the lives of those who are the most marginalized in our society.”

Ever since 2020, when George Floyd, an African American, was murdered by police, corporate America has stepped up its focus on equity. The Business Roundtable, a group of CEOs of the nation’s leading corporations, formed a special committee to address racial equity and justice. Companies such as Walgreens Boots Alliance announced goals to increase the share of people of color in leadership positions. Macy’s, Nordstrom, and other retailers joined the Fifteen Percent Pledge, a movement to get products from Black-owned firms onto 15% of America’s store shelves.

“All of a sudden, you began seeing movement towards metrics,” says Mr. Rubinstein. It’s these racially based quotas that he views as unconstitutional. His foundation, started by former Trump administration senior adviser Stephen Miller, has filed complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, charging that Starbucks, Morgan Stanley, McDonald’s, and others have violated the law with their hiring and diversity practices.

Another conservative group, the National Center for Public Policy Research, sued Starbucks executives and directors for setting diversity targets for hiring and promotion as well as in their supplier base, and linking executive pay to the achievement of these goals.

The Supreme Court’s ruling late last month against affirmative action at universities puts new wind in their sails. After Texas A&M hired Kathleen McElroy in June to lead its journalism department, she came under fire from conservative groups for her previous work at The New York Times, where she researched the relationship between race and the news media. Ms. McElroy stepped down, and on Friday, so did the university’s president, Katherine Banks, citing “negative press.”

As a legal matter, affirmative action in university admissions and corporate DEI are separate, governed by different laws. It is already illegal to hire someone because of their race or ethnicity. But as a practical matter, the court’s ruling increases the legal jeopardy of corporations. For example, Chief Justice John Roberts’ “zero-sum” reasoning that a race-based benefit given to some applicants necessarily disadvantages others could also apply to corporate DEI practices, such as hiring and awarding contracts.

“This very forceful statement from the chief justice about the ways in which race can and cannot be used in zero-sum decision-making is going to have an impact on corporate DEI,” says Ishan Bhabha, partner and co-chair of the DEI Protection Task Force at the Jenner & Block law firm in Washington, which represents universities and companies. Already, corporations are taking a closer look at their initiatives and how they can reduce their legal vulnerability.

Both sides expect a surge in anti-DEI suits, putting corporations between a rock and a hard place. Under pressure from many liberal shareholders and employees to increase their DEI efforts, corporations now face the prospect of conservatives filing suit to pare back those initiatives. These range from hiring and promotion to corporate board composition.

One challenge for diversity advocates is that in many cases, a more diverse workforce doesn’t appear to lead to a more profitable company or a more empowered workforce, researchers say. What’s needed, they add, are the other parts of the DEI equation: a workplace culture of (1) equity, in which all employees feel they are treated fairly and (2) inclusion, in which they feel empowered and free to express their ideas. It’s what Alex Edmans, professor of finance at London Business School, calls “true DEI.”

“You want the respondent people to say, ‘I’m treated well here’; ‘This is a psychologically safe place to work’; ‘People are treated the same regardless of their age, race, and sex’ – all of those things,” says Mr. Edmans, whose May 2023 study focused on Fortune magazine’s annual list of the 100 best companies to work for in America. “And we’re not seeing that’’ even among employers that have altered hiring to become more racially and ethnically diverse.

That leads to a deeper question: Is the hiring and promotion of a broad range of races and ethnic groups the best way to achieve the diversity of thought and outlook that corporations are looking for? Or do other factors, such as life experience, education, and income level, matter more?

“I still have experienced discrimination on the basis of appearance,” says Mr. Edmans, who is of Asian descent. “And so if I was to serve in the board of directors – and I am on several boards – I would count as a minority. But maybe a white male who never went to university, he would add more to socioeconomic diversity than me.”

To minimize their legal exposure, corporations should broaden their diversity criteria beyond race to include such things as life experience, according to Mr. Bhabha of Jenner & Block.

Others counter that the disparities in racial and ethnic achievement in the workplace remain so large that they need to remain a focus for employers. For example, the typical Black worker earned 24% less than their white counterpart in 2019, according to a report by the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal think tank based in Washington. And that gap was larger than the 16% gap in 1979, even though African Americans have narrowed the Black-white gap in high school and college completion during that time.

In light of the court’s action, defenders of affirmative action expect a retrenchment of corporate DEI programs but not their end.

“In this day and age in the 21st century, you can’t just say, ‘You know what, we’re kind of done with that DEI thing,’” says Mr. Bhabha. The advantages of being able to draw from a greater talent pool and to address an increasingly diverse customer base make diversity a corporate imperative, he adds. “Many companies completely, correctly recognize that from a business perspective, just from a business balance-sheet perspective ... DEI is actually critical to the success of that business.”

British government at odds with public in immigration crackdown

High immigration rates motivated many Britons to favor leaving the European Union in 2016. But migrant numbers have risen to record heights since then, and the public seems largely unconcerned, instead happy with “controlled openness.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When Britons voted to leave the European Union in 2016, a powerful reason was the level of immigration – and the promise that the government would “take back control” of who is allowed to live in the United Kingdom.

Seven years on, net migration has hit an all-time high, but the electorate seems relaxed and indeed welcomes immigrants who work in the health sector, pick fruit, or fill other job vacancies.

The ruling Conservative Party, though, which faces general elections next year, is still strongly exercised about immigration rates, and Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is under pressure to fight those elections on an anti-immigrant platform. But he is in a bind: The vote will likely turn largely on the performance of social services, which depend on migrant labor.

The government has tightened up the rules on foreign students bringing their dependents to Britain, but that is not going to make much of a dent in the numbers. Mr. Sunak may choose to focus on deporting asylum-seekers who enter the country illegally, to distract attention. Those migrants in particular are less popular with the public.

But overall, says Sunder Katwala, an immigration expert, “there’s a sign of consensus for what you might call controlled openness.”

British government at odds with public in immigration crackdown

The central promise of Brexit, when British voters decided in 2016 to withdraw from the European Union, was that the United Kingdom would be able to “take back control” over who is allowed to live there. Polls at the time showed that around two-thirds of voters wanted less migration.

Seven years on, immigration has lost much of its political sting. Voters no longer consider it a top concern: Only 4 in 10 voters say they want less migration, the lowest level in decades. A small but growing minority now even favors allowing more migrants in.

But while the public seems more relaxed about the issue, the ruling Conservative Party is decidedly not.

Anti-immigration hard-liners in the party are pressing Prime Minister Rishi Sunak to fight next year’s election on a pledge to cut net migration, which hit an all-time high of 606,000 last year. But Mr. Sunak faces a dilemma: The vote will likely turn largely on the performance of social services, which depend on migrant labor.

The government responded in May to the release of last year’s migration data by announcing limited visa restrictions on international students, whose numbers have surged in response to the government’s own policy to make U.K. universities more attractive to non-EU students after Brexit. More than 700,000 international students are currently in the U.K.

But the new policy, which only applies to graduate students bringing dependents, is unlikely to bend the curve by itself or satisfy the Conservative hard-liners who fret that voters will punish them for allowing in too many foreigners.

That immigration remains so politically thorny for Conservatives is largely a problem of their own making, says Rob McNeil, deputy director of Oxford University’s Migration Observatory. “The challenge we’ve got is that for over a decade, this idea has been put forward that there’s a correct number we should be hitting,” he says, which “massively oversimplifies the issue.”

The fixation with a net migration target dates back to 2010, when David Cameron, then the leader of the Conservative Party, sought to detoxify the debate over migration by imposing “balanced levels” of net migration, which he proposed to hold to tens of thousands a year.

That proved impossible to achieve, but the idea of a target persists in Tory ranks.

Keen on immigrants, but not on immigration

Mr. Sunak is not the first Conservative leader to find himself in this bind: Since 2010, the center-right party has won four successive elections on a platform of cutting immigration, only to see numbers rise. Mr. Sunak has largely stuck to the catechism.

“Numbers are too high. It’s as simple as that, and I want to bring them down,” Mr. Sunak said in a TV interview in May.

The prime minister has separately pledged to tackle an increase in asylum-seekers crossing the English Channel in small boats from France, by passing a new law that will prevent them from claiming asylum if they arrive illegally. The public has less sympathy for migrants who come without authorization – more than 45,000 of them arrived last year – than those who seek refuge with prior approval, such as Ukrainians.

Paradoxically, although a significant number of voters, including a majority of Conservatives, think migration should come down and fault the government for not doing enough to control it, polling finds strong public support for migrants who work in the National Health Service, as well as for those who come to pick fruit and fill other job vacancies. Students, scientists, and bankers are also welcome.

“Britons may not much like immigration, but they are keen on immigrants,” an Economist columnist noted recently.

When it comes to foreign students, who pay higher tuition fees than U.K. residents, views are highly favorable, says Lord Karan Bilimoria, the chancellor of the University of Birmingham and the president of the U.K. Council for International Student Affairs. He says that in targeting students as a way to cut net migration the government has put ideology before public opinion.

“The public is totally for international students. They don’t see international students as immigrants,” says Lord Bilimoria, an Indian-born entrepreneur. He argues that students shouldn’t even be counted in net migration data, since most return home eventually.

One of those students is Kennedy Onaiwu, a Nigerian student who enrolled last year at the University of Hertfordshire for a master’s degree in environmental management. After he graduates in September, he will be eligible for a two-year work visa, which is a major draw for students like him.

“They come and spend in this economy,” says Mr. Onaiwu, referring to foreign students’ tuition fees and living expenses. “You can’t expect them to go back ... empty-handed.”

Still, Mr. Onaiwu can count himself fortunate in his timing. Last year, he married a fellow Nigerian who recently moved to join him here. As his dependent, she is also eligible to work in the U.K. for the next two years.

Now that pathway has been closed.

That will be a blow to British universities. At the University of Hertfordshire, where Mr Onaiwu studied, international students make up more than 40% of the student body and enhance the experience for everyone, says Quintin McKellar, the university’s vice chancellor.

In an emailed statement, Professor McKellar says that demand from overseas for places next year remains strong despite the new visa rules, but he feels it was “short-sighted and detrimental” to put up such barriers. “We should be celebrating that so many international students want to study in the UK and actively welcoming them and the many benefits they bring – not pushing them towards other countries,” he argues.

Toward “controlled openness”

Anti-immigration groups say students who bring their families put additional pressure on schools, housing, and other public services. But migrants are more likely to be working in hospitals and care homes than using them: The number of work visas issued for these sectors almost tripled to 211,000 in the year to March 2023.

Take Mr. Onaiwu: He’s working in the care sector while he waits to graduate. His wife, a nurse, is preparing to take an exam that would allow her to work for the National Health Service.

He says the new policy on dependents will make some Nigerians think twice about the U.K. “This is not the best move. It’s actually discrimination. You can’t separate families ... just because you want to regulate your [immigration] system,” he says.

Analysts say net migration to the U.K. has likely already peaked and will be falling by next year. Whether it will matter much to voters is unclear, says Paul Taggart, a professor of politics at the University of Sussex who studies populism. As an issue, though, “it’s always bubbling under and it can come back,” he says.

Mr. Sunak may focus on reducing illegal boat crossings in order to distract attention from overall migration numbers and his government’s own post-Brexit immigration policy, which has been more liberal than some had expected. Yet to some extent, his hands are tied for a simple reason of migration math, says Professor Taggart.

Net migration – the number of arrivals minus the number of departures – is decided as much by the latter as the former, and “you can’t stop people leaving the country,” he points out.

The government is still trapped in its pursuit of a net migration target, but Brexit has nonetheless achieved what few at the time predicted – breaking a pattern by which rising levels of migration fuel rising anti-migrant attitudes. Net migration is higher than ever. But “we’re not seeing a massive public freak out about this,” says Mr. McNeil of Oxford University.

For voters who wanted an end to free movement from the EU, Brexit has delivered. “That has been cathartic,” says Sunder Katwala, director of British Future, a think tank focused on immigration issues. “There is significant growth in confidence in how we handle migration.”

That confidence, he adds, undergirds a new political reality for migrants. “There’s a sign of consensus for what you might call controlled openness,” he says.

Editor's note: The original story misstated the effect of visa restrictions on the University of Hertfordshire.

From kids’ books to gritty movies, a year of sanitizing culture

Whenever efforts to sanitize the works of the past arise, like now, scholars say those arguments are really about the future – and who gets to decide what’s possible.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Whether it’s Agatha Christie or James Bond, publishers this year have been scrubbing novels of outdated or potentially offensive language.

Now, the effort has quietly spread to movies. A number of streaming services in the United States this summer removed a scene that contained racial slurs in “The French Connection,” a 1971 film that won the Academy Award for best picture and influenced the gritty style of films that came to define the 1970s.

Over 200 years ago, Thomas Bowdler and his sister Henrietta edited the works of Shakespeare, removing anything that could be considered blasphemous or sexual – providing a “family” Shakespeare that could be read aloud with children and women present. Their efforts added a new pejorative to the English language: to bowdlerize.

“The debates we’re seeing around censorship, adaptation, editing classic works, or however you’re going to frame it, isn’t new,” says Tobin Shearer, director of African American studies at the University of Montana in Missoula. “We have returned to these things repeatedly as a nation. They are touchstones for recurrent struggles that always surround religion, sex, violence, social boundaries.”

From kids’ books to gritty movies, a year of sanitizing culture

The tradition to alter or otherwise censor certain artistic productions goes back centuries.

The reasons can vary, but from fig leaves on sculptures to TV versions of classic films, when a work of art has a wider and more varied audience, censors work to cover, replace, or reshape the originals to make it more publicly palatable.

Over 200 years ago, the English physician Thomas Bowdler and his sister Henrietta edited the works of Shakespeare, removing anything that could be considered blasphemous or sexual – providing a “family” Shakespeare that could be read aloud with children and women present. Their efforts added a new pejorative to the English language: to bowdlerize.

Unlike banning or full censoring, bowdlerizing certain works of art can include a positive intention. There’s a recognition of a production’s value and a desire to increase its audience, not shut it off. At the same time, however, like full censoring, removing offending scenes or language represents a kind of social control over audiences, a maintaining of the status quo.

“The debates we’re seeing around censorship, adaptation, editing classic works, or however you’re going to frame it, isn’t new,” says Tobin Shearer, professor of history and director of African American studies at the University of Montana in Missoula. “We have returned to these things repeatedly as a nation. They are touchstones for recurrent struggles that always surround religion, sex, violence, social boundaries.

“And I think, as an interpreter of the past, these struggles are always much more about the future,” he continues. “What are the possibilities of imagining what is yet to come? Who gets to decide that? These questions are baked into these recurring debates.”

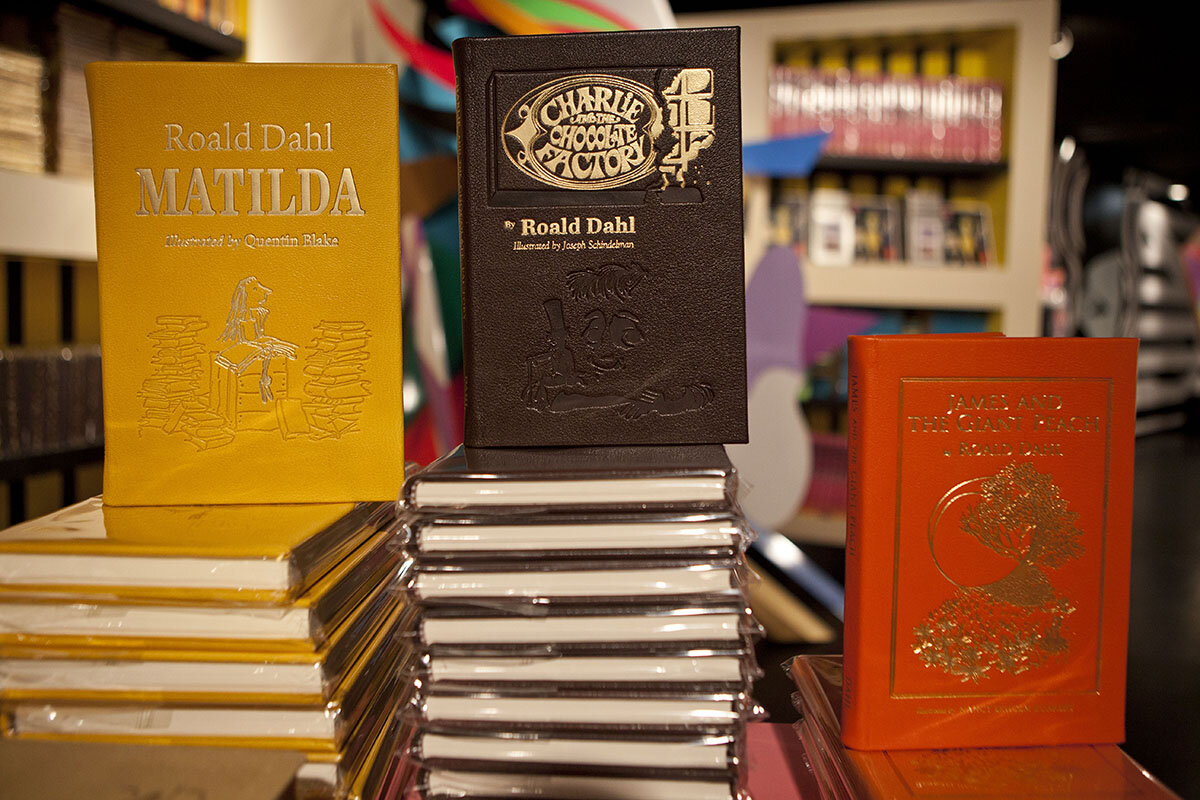

Earlier this year, publishers cleaned up language from the children’s books of Roald Dahl and the mysteries of Agatha Christie, removing potentially offensive language about body types or ethnicity. After a widespread backlash, Penguin announced it would keep the original version of Dahl’s books for sale as well. This year marks the 70th anniversary of the first James Bond novel by Ian Fleming; the publisher announced it would reissue his novels after scrubbing them of outdated references and racist language.

A number of streaming services in the United States this summer removed a scene that contained racial slurs in “The French Connection,” a 1971 film that won the Academy Award for Best Picture and influenced the gritty style of films that came to define the 1970s.

“There’s a real moral panic happening within both the left and the right about what people are capable of understanding and tolerating and learning from,” says Bill Yousman, professor of communication and media studies at Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. “My reaction to the ‘French Connection’ changes was, okay, let’s not have this fictionalized cop use the N-word, because then that means that police never use racial slurs? And now I can feel better; I can go to sleep with the notion that, well, there is no racism in doing police work, and, no, they don’t talk like this?

“It’s a real dismissal, I think, of the audience, or that belief that people are capable of understanding what a film or book is trying to convey, the larger social context in which it was originally written, and what it’s trying to say about society,” he says.

Han shot first

Earlier this year, director Steven Spielberg said he made a mistake when he altered his 1982 film “E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial” in the early 2000s. He had been concerned about a scene in which armed federal agents approached children in the film with their firearms drawn, so he altered the scene with the agents carrying walkie-talkies instead.

“I should have never done that because E.T. is a product of its era,” he said during a panel discussion at the Time100 Summit in April. “No film should be revised based on the lenses we now are either voluntarily or being forced to adhere to,” he said, saying the original versions of classic films should be considered “sacrosanct.”

In the original “Star Wars,” it was the character of Han Solo who was altered, even as new scenes were added as technology improved. In a famous scene at the Mos Eisley cantina, the original shows the swashbuckling character preemptively shoot a bounty hunter under the table. In the altered version, Han Solo shoots only after the bounty hunter, Greedo, draws first.

“It’s easy to make fun of these things, and I do sometimes, but I do think that there’s something troubling about it,” says Professor Yousman. “There’s a certain level of censorship that’s coming, I think it’s fair to say, from all sides of the political spectrum now.”

Another approach

Instead of altering content that could be considered problematic, the Walt Disney Co. issues a warning message at the start of some of its classic animated films, including “Dumbo,” “The Jungle Book,” and “Peter Pan.”

“This program includes negative depictions and/or mistreatment of people or cultures,” the initial warning reads. “These stereotypes were wrong then and are wrong now. Rather than remove this content, we want to acknowledge its harmful impact, learn from it and spark conversation to create a more inclusive future together. Disney is committed to creating stories with inspirational and aspirational themes that reflect the rich diversity of the human experience around the globe.”

The motives for editing out offensive language and scenes from certain works are understandable, says Paul Levinson, professor of communication and media studies at Fordham University in New York. “No decent person wants to be entertained with racial slurs and insults,” he says, “and we’re doing our best to extirpate words like that from public society.

“But I think still that the safest and best thing to do in terms of the well-being of a free democratic society is to leave these works alone,” he continues. “You can make a decision about whether a work is age-appropriate, but when you start changing works to make them more suitable, it’s just as easy to start banning books – and that’s not to protect anyone. That’s to demonize certain people so that kids will have no knowledge of them.”

Indeed, sanitizing the past only tends to foreclose the possibilities of the future, says Professor Shearer at the University of Montana.

“I’m a progressive, but I get very uncomfortable with the efforts to censor past historical documents because I think it’s a matter of equipping our youth or others – I want them to confront that past and to know exactly what it looked like. I don’t want to pre-screen it for them,” he says.

“On the one side,” he adds, “you can see with the book-banning efforts in so many states a sense that we don’t want our youth to really be able to engage with ideas that might make them think alternative thoughts – thoughts that could rearrange the way we do relationships, or that could rearrange the way we shape our political environment.”

Centuries-old Jerusalem soup kitchen serves up ‘food with dignity’

Much has changed since Jerusalem’s Tikiya soup kitchen was built in 1552. Certainly its menu. But for the local community, its mission is timeless. Says the assistant chef who grew up nearby: “This kitchen is a part of our charitable identity.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Down an almost-hidden passageway in Jerusalem’s labyrinthine Old City is Tikiya Khaski al-Sultan, a soup kitchen that dates to the height of the Ottoman Empire. It is a lifeline for modern-day Jerusalemites facing rising costs and needing “support without judgment.”

Six days a week, 52 weeks a year, head chef Samir Jaber and his staff arrive at 5 a.m. to begin preparations. On a Monday morning, chickens are boiling in giant vats, delivery boys are stacking crates of vegetables in the high-vaulted stone room, and Mr. Jaber is frantically checking inventory.

Centuries ago, the soup kitchen served individuals a cracked wheat porridge known as tikiya soup; today, it serves full meals to be taken home for 300 families, some 1,500 to 1,800 people. “We want people to eat just as we eat at home,” Mr. Jaber says.

At 11:30 a.m., as recipients enter the kitchen, the head chef and his staff move as fast as possible, scooping whole chickens, rice, and potatoes into containers of all shapes and sizes.

“We don’t feel like beggars. We feel like respected individuals whose lives are being given added support,” says Rana, a mother of three. “This kitchen is a pillar on which we can stand. ... Plus, the food is quite good.”

Centuries-old Jerusalem soup kitchen serves up ‘food with dignity’

Rana steps off Al Wad Street onto a winding narrow stairway, following an almost-hidden passage in the labyrinthine Old City that has led to generosity for nearly 500 years.

Carrying two bucket pails and a shopping bag packed with empty Tupperware, she passes Mameluke-era architecture as part of her daily route – a journey to feed her family.

“This is where we get food with dignity,” says the mother of three. “This is where the Holy City’s generosity is always kept warm.”

Tikiya Khaski al-Sultan, a soup kitchen that has been serving up meals since the height of the Ottoman Empire, is a lifeline for modern-day Jerusalemites who face rising costs and unemployment and are in need of “support without judgment.”

Yet the centuries-old charity also serves up some “good cooking.”

“This isn’t canned food or handouts,” Rana says. “This is a meal for all.”

A woman of influence

The Tikiya soup kitchen and sprawling complex were built on a hill facing the Al-Aqsa Mosque/Temple Mount in 1552 on the order of Roxelana, wife of Ottoman Sultan Suleiman II.

With a reputation for generosity, a kind heart, and a strategic mind, Roxelana, one of the most influential women in the history of the Ottoman Empire, established the soup kitchen and guesthouse to serve travelers, students, religious scholars, residents, and disadvantaged people. It was not only to highlight Jerusalem’s hospitality, but also to cement residents’ dependence on the Ottomans, who had extended their rule over the Holy City 35 years prior.

The complex once included an orphanage, guesthouse, and a school; today, the 16th-century complex and courtyard has 25 rooms, a school, large domes, views of the Old City – and a bustling kitchen.

On a Monday morning, chickens are boiling in giant aluminum vats; delivery boys are stacking crates of tomatoes, onions, and bell peppers in the high-vaulted stone room; and head chef Samir Jaber is frantically checking his inventory, doing calculations for ingredient ratios.

Much has changed over the ages.

The Jordanian government now manages the kitchen at the direction of the Hashemite monarchy.

Centuries ago, the soup kitchen served up a cracked wheat porridge, known as dahsheesha, or tikiya soup; today, the kitchen serves full meals. Instead of feeding individual visitors, it provides food to be taken home for entire families.

And it caters to Jerusalemites’ discerning palates with a sense of mission.

“We want people to eat just as we eat at home,” Mr. Jaber says as he checks on the chickens.

“Jerusalem is a home for all of mankind, which makes this the world’s kitchen. We are making home-cooked food for humanity.”

“Part of the city’s fabric”

Six days a week, 52 weeks a year, Mr. Jaber and his staff arrive at 5 a.m. to begin preparations for meals for 300 families, some 1,500 to 1,800 people – cleaning and prepping meat, gathering and washing vegetables, soaking vats of rice.

During Ramadan, the kitchen ramps up its production to serve visitors to Jerusalem, from the West Bank and farther afield, serving more than 1,000 families a day.

Recipients and chefs laud the menu’s rotation of meals and balanced diet that includes mulikhiya jute leaves; stuffed grape leaves; bean and beef stew; maqloubeh chicken, eggplant, and rice; okra and beef; and the crowd-pleasing mansaf lamb and yogurt.

The kitchen also keeps batches of plain, fully cooked ingredients that residents can take home to add their own personal touches.

Ahead of the 11:30 a.m. rush, assistant chef Ramsi al-Sayli swiftly but precisely dices tomatoes to add to today’s dish of shish tawook chicken in tomato sauce with potatoes.

The veteran chef, who has worked in hotels in Israel and the occupied territories serving well-heeled clientele such as diplomats, tech moguls, and celebrities, says he is “much happier” being assistant chef in “humanity’s kitchen.”

He grew up and lives just a few yards away, near what are now known as the Tikiya steps.

“Everyone knows about the Tikiya from when they are young; it is part of our neighborhood and part of the city’s fabric,” he says as he moves on to dicing onions.

“We Jerusalemites like to be charitable and welcoming to all who are in need. This kitchen is a part of our charitable identity,” he says.

“We don’t feel like beggars”

At 11:30, mothers, fathers, and older people line up at the courtyard, food containers in tow.

As recipients enter the kitchen, the head chef and his staff move as fast as possible, piling in potatoes, scooping in whole chickens, and shoveling steaming-hot rice into buckets, coolers, and containers of all shapes and sizes.

“We don’t feel like beggars. We feel like respected individuals whose lives are being given added support,” Rana says, balancing buckets of potatoes and cooked chicken that weigh down each arm.

“This kitchen is a pillar on which we can stand. It allows us to live and to continue to live in Jerusalem.”

“Plus,” she adds, “the food is quite good.”

Um Salem, whose father and son have disabilities and whose household does not have a single working adult to bring in income, says her family relies on the kitchen not only to subsidize their lives – but also for special occasions.

“They cook us special meals upon request. I asked for pastries so we can celebrate my son’s graduation, and they baked it for us so we could host,” says Um Salem. “It’s as if we have family helping us out, not a charity taking pity on us.”

Rising cost of food

Difficult times are mounting for many Old City residents, with unemployment and underemployment high.

As many of the Palestinians in the Old City do not hold Israeli citizenship, they often fall through the cracks of services provided by Israel, the Palestinian Authority, and Jordan.

Joining the soup kitchen’s six-days-a-week line are merchants who shuttered their shops or lost their life savings during the pandemic and have yet to recover.

The cost of living, and of food, is rising again in Jerusalem.

Although the soup kitchen was funded in Ottoman times by a waqf, or charitable trust, collected from the annual production of farms, shops, bathhouses, and flour mills, it depends now on donations from individuals and prayergoers in Jordan, Jerusalem, and beyond, which are gathered by Jordan’s Ministry of Awqaf and Islamic Affairs.

As money is becoming tighter for many Jordanians and Jerusalemites, and donations are starting to slow, charitable individuals are stepping up to keep the food coming.

“Crises and wars come and go, but the desire to give charity remains, good deeds remain, and generosity remains,” Mr. Jaber says as he closes up the kitchen at the end of the day.

“Jerusalem’s heart remains open, and so does our kitchen.”

How my toddler reawakened my sense of wonder

In the midst of the ordinary, moments of awe have the power to transform us. Paying attention to life’s tiny wonders can infuse each day with unexpected beauty.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Samantha Laine Perfas Contributor

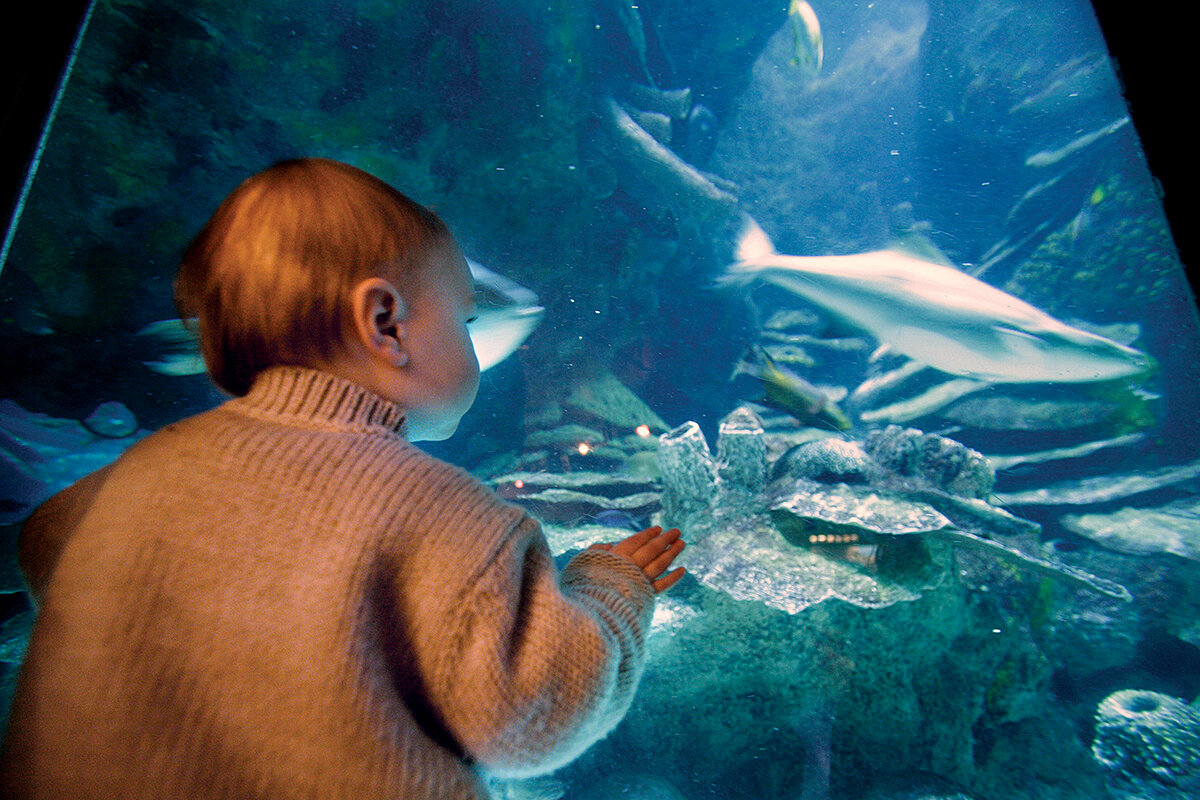

Caring for a toddler can be like using a VHS tape: Wake up, eat, play, sleep; rewind, repeat. To spice things up, I bought a membership to the New England Aquarium in Boston. That decision proved to be a turning point.

On our way to the exhibits, a flash of color catches my eye. I turn the stroller and head to a part of the aquarium I’d missed the previous time we were here. A nearly floor-to-ceiling tank fills one section of wall. Inside are hundreds of tropical fish of every shape and color I can imagine. I crouch down by my son to point them out.

But there’s no need: He’s transfixed. The look of wonder on his face is so raw, so pure. I’m speechless. I let myself get lost in the wild array of color. When we finally moved on, I consciously slowed down and looked at my son at each exhibit, trying to see through his eyes. His wonder had transformed my experience. What else had I been missing?

Since that day at the aquarium, I’ve taken more cues from my son. I have a choice, I see now. I can let routine, worry, and self-absorbed thinking sink my day into drudgery. Or I can choose to look at the world differently.

How my toddler reawakened my sense of wonder

Caring for a toddler can be like using a VHS tape: Wake up, eat, play, sleep; rewind, repeat. My days blur together as I try to occupy my 18-month-old son for more than two minutes. To try to spice things up, I bought a membership to the New England Aquarium in Boston. That decision proved to be a turning point.

The first time we went was a disaster. We battled hordes of fussy babies, grouchy children, and frazzled parents on a crowded weekend afternoon. One of us ended up close to tears: me. Determined to redeem our trip and my investment, I tried again – on a weekday this time. If my hunch was correct, the place would still be busy, but we’d have room to breathe – and wouldn’t have to throw any elbows to get a peek at the octopus.

So I crammed everything I could into the diaper bag and loaded up the bottom of the stroller with water bottles, snacks, and emergency toys. I strapped my little guy into his stroller, attached his “adventure pacifier” to his onesie, and off we went.

This time, when we get to the aquarium, I’m relieved to find that I am correct. The lights are dim, a few couples meander past, and a group of kids on a field trip is being shepherded around. As we pass the penguins on our way to the exhibits, a flash of color catches my eye. I turn the stroller and head to a part of the aquarium I’d missed the previous time. A nearly floor-to-ceiling tank fills one section of wall. Inside it are hundreds of tropical fish of every shape and color I can imagine. Some dart around playfully, while others slowly patrol the bottom. I smile and crouch down by my son to point them out.

But there’s no need: He’s transfixed. His eyes are open wide, following the movements of the fish. His little jaw has dropped; the corners of his mouth are turned up. My breath stops, and I feel my throat tighten. The look of wonder on his face is so raw, so pure. I’m speechless.

I turn back to the fish tank and let myself get lost in the wild array of color. It is like seeing the fish for the first time: yellow fish, brighter than the sun; the sharp contrast of the clownfish’s stripes; the slow fanning of their fins, floating and twirling in the water. This beauty had always been there, but my rush to do and see more had prevented me from seeing and experiencing anything at all.

We watched the fish. We let the wonder of their color, movement, and form fill the space. When we finally moved on, I consciously slowed down and looked at my son at each exhibit, trying to see through his eyes. His wonder had transformed my experience. His being so in tune with his surroundings had alerted me to do the same. What else had I been missing?

Since that day at the aquarium, I’ve taken more cues from my son as we navigate our days. And while they still contain cycles of chores and tasks, there’s also a new awareness of nuance and complexity on my part. I have a choice, I see now. I can let routine, worry, and self-absorbed thinking sink my day into drudgery and unease. Or I can choose to look at the world differently. I can pursue beauty and awe. Rather than simply doing “play, rewind, repeat,” I can strive to realize all the joy to be found in pressing “pause” and taking in the moment.

I used to feel I had to reserve awe and wonder for big things, like the northern lights or a vacation sunset or one of the world’s many architectural majesties. But in doing that, I was missing the small things that make life extraordinary: How joyful it is to hear someone laugh; the delight (and terror) of a goat eating from the palm of your hand; picking a flower from the side of the road and noticing how perfect each petal is. Each time I see my son’s face light up at these tiny wonders, I feel a part of me soften. I remember that there is so much good in the world, if I only allow myself to see it.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Why the Taliban can’t ignore girls’ education in the Muslim world

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

With little fanfare, a Taliban delegation from Afghanistan quietly visited the world’s most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia, in July. The trip was yet another attempt by the rulers in Kabul to gain foreign recognition. One place the delegation certainly did not visit was the Cisarua Refugee Learning Centre outside the capital, Jakarta.

There they might have seen why the rest of the world has kept the Taliban at arm’s length. The center is educating Afghan girls who have fled their country. “Here, women can be a boss; they can be teachers, they can be students ... they are strong,” Khatera Amiri, manager of the center, told Al Jazeera. In other words, the Afghan girls are treated as equal to the boys.

Gaining official recognition from Indonesia is key to the Taliban’s hunt for friends in the Muslim world. Yet Indonesian leaders insist the Taliban end their ban on girls going past the sixth grade.

“Today, we are able to do more things [in Indonesia] because we have women who excel,” says Yahya Cholil Staquf, chair of the country’s largest Muslim association.

Why the Taliban can’t ignore girls’ education in the Muslim world

With little fanfare, a Taliban delegation from Afghanistan quietly visited the world’s most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia, in July. The trip was yet another attempt by the rulers in Kabul to gain any sort of foreign recognition of their harsh regime nearly two years after taking power. One place the Afghan delegation certainly did not visit was the Cisarua Refugee Learning Centre outside the capital, Jakarta.

There they might have seen why the rest of the world has kept the Taliban at arm’s length. The center is educating Afghan girls who have fled their country. “Here, women can be a boss; they can be teachers, they can be students ... they are strong,” Khatera Amiri, manager of the center, told Al Jazeera.

In other words, the Afghan girls are treated as equal to the boys. Indonesia itself – unlike the Taliban – puts such an emphasis on educating girls that they outnumber boys at the secondary level. “Indonesia can serve as an important model for the Taliban of how Muslim nations and faith-based organizations can play an important role in expanding girls’ education,” M. Niaz Asadullah, a University of Malaya professor, wrote in The Conversation in 2021 after the Taliban takeover.

Most Muslim-majority nations view educating girls as crucial to their society. “Every time I went to one of these Muslim countries, they did reinforce the fact that Islam did not ban women from education or from the workplace,” says Amina Mohammed, the United Nations deputy secretary-general, who is herself a Muslim. Islam, she added, is “a living religion,” and that influences how the world can move “the Taliban from the 13th century to the 21st.”

Gaining official recognition from Indonesia is key to the Taliban’s hunt for friends in the Muslim world. Yet Indonesian leaders insist the Taliban end their ban on girls going past the sixth grade as well as the ban on women working in many government jobs or with humanitarian agencies. “Today, we are able to do more things [in Indonesia] because we have women who excel,” Yahya Cholil Staquf, chair of the large Muslim association Nahdlatul Ulamam, told BenarNews last year.

The U.N. regards Afghanistan under the Taliban as the most repressive country in the world regarding women’s rights. Yet the Taliban are desperate to boost their ruined economy and to maintain legitimacy, both inside and out the country.

The regime’s leaders pay “close attention to what the international community thinks,” writes Andrew Watkins, an expert on Afghanistan at the United States Institute of Peace. Their level of detail on policies toward women, he adds, suggests the regime feels compelled to explain and defend its actions to the Afghan people and the world.

The Taliban delegation’s visit to Indonesia was a chance to perhaps win over – but also perhaps listen to – another Muslim country.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

‘One thing is needful’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Kim Haig

As we prioritize prayer to our infinitely good God, we find that stress about the many details of our lives falls away.

‘One thing is needful’

Often when I’m fretting over a problem, whether a personal issue or a world crisis, I am reminded of the Bible’s Mary and Martha when they hosted Jesus in their home (see Luke 10:38-42). Martha felt burdened about preparing the meal. Mary, on the other hand, simply sat at Jesus’ feet listening to his teaching. When Martha came to Jesus complaining about her sister’s failure to help, Jesus gently corrected her. He swept aside social codes with his statement “One thing is needful: and Mary hath chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her.”

Here Jesus instructs us to follow a higher law – to sit at the feet of Christ – that is, focus on nourishing our understanding of God, Spirit, through Christ, the true idea of God, which is present at every moment, revealing our perfect selves already at the apex of harmony.

Perhaps it seems that focusing only on good would be ignoring evil; it’s important not to be selfish or clueless when it comes to acknowledging the troubles of humanity. But we need to equip ourselves with healing prayer to handle the claims of evil. This work consists of diligently lifting our thought above the tumultuous picture of human struggle to the view that Jesus had of everyone as made in God’s very likeness, incapable of expressing anything but love, peace, and intelligence.

Jesus had the clearest and most correct perspective of anyone ever to walk the earth, and this enabled him to fulfill his God-ordained mission of saving humankind from its woes. Jesus didn’t just look on these woes without addressing them; through his Christly thought, he healed all kinds of problems. In place of a diseased or sinning mortal, he “beheld in Science the perfect man.... In this perfect man the Saviour saw God’s own likeness, and this correct view of man healed the sick” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” pp. 476-477).

Mrs. Eddy discovered the divine laws behind Jesus’ healing works and named this discovery Christian Science. She proved that there is a Science based on spiritual law that enables us to overcome material ills by raising thought above what is actually a false picture. Through an understanding of Christian Science, we all have this inherent ability to sit at the feet of Christ – to see everything in the world as it truly is in the wholly harmonious kingdom of heaven right here and now. To perceive this true sense of harmony, we must put into practice, diligently and with humility, what we understand of true being.

These ideas helped me a few years ago when my husband and I were building a house. This project was the culmination of many years of prayer and listening to God for direction. Yet, one day on the construction site, I felt very frustrated. Costs were soaring out of reach, and work was being done at a much slower pace than needed. One day, as I was busily painting outside on a ladder, I suddenly fell onto a concrete stoop.

Immediately, I got up and declared strongly that “accidents are unknown to God” (Science and Health, p. 424), so they must be unknown to me as God’s child, made in His image and likeness, as the Bible says. It didn’t appear that anything was broken, but an ugly bruise was developing on my arm, and my head was banged up. I called a Christian Science practitioner for prayer.

As I continued to stick with the truth that God, good, was keeping me safe in every way, I rejected the claim that evil had any place in God’s kingdom. Rather than fretting over innumerable details of the construction, I chose to sit at the feet of Christ and take in the message of God’s allness and care.

I felt so comforted knowing that so long as I kept my focus on what God was doing, I would see that I was totally cared for. And every detail of the construction would be cared for as well. Within a short time, the bruising vanished from my arm, and the other injuries also cleared up quickly. We finished the house and moved in just days before a planned family event.

The example of Mary sitting at the feet of Jesus shows us how crucial it is to acknowledge and accept the message that we are the loved children of God.

Adapted from an article published in the July 10, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

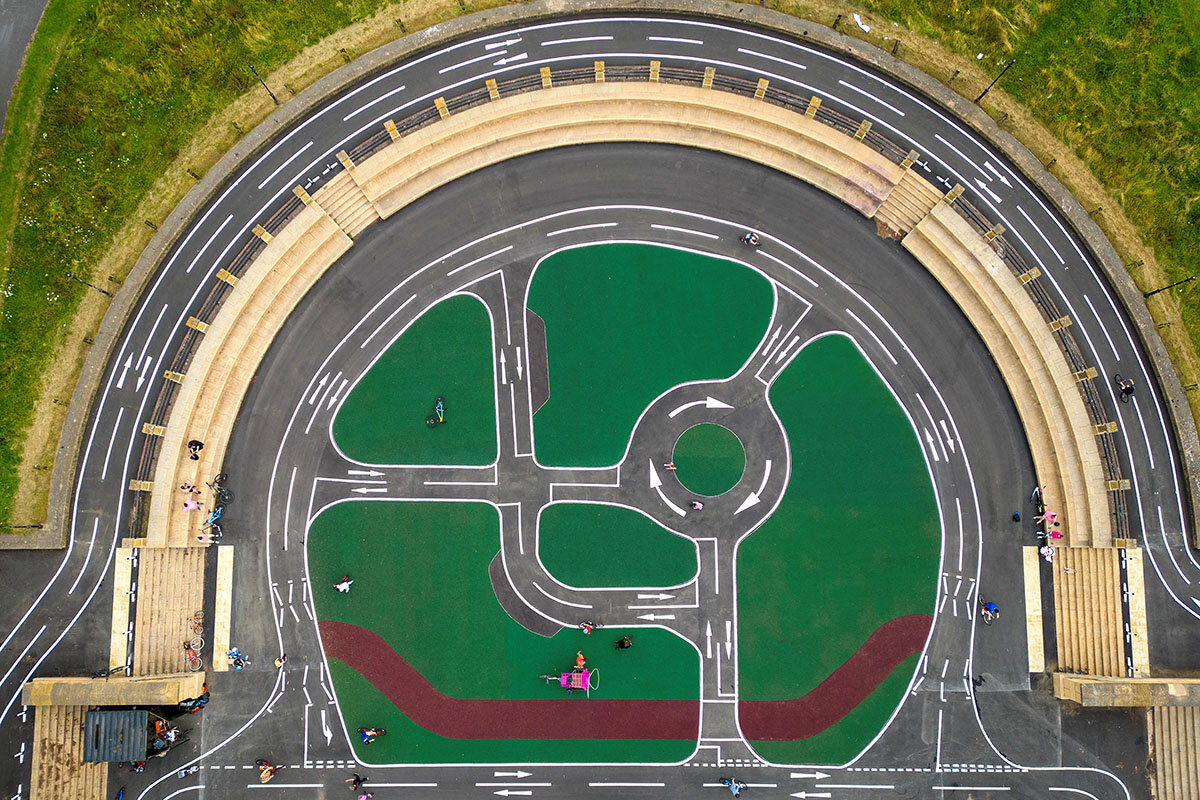

Going in circles

A look ahead

We’re so glad you could join us today. Please come back tomorrow, when Christa Case Bryant explores how Washington is finally waking up to the challenges of artificial intelligence and the need to act. We’ll also have a story on the collapse of Hunter Biden’s plea deal.