- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

From Berlin, with love

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

By next week, I will be living in Berlin.

No, I am not part of some editor exchange program. You should not expect the chief of the Süddeutsche Zeitung to announce a seven-part Monitor series on Oktoberfest. This is about my family – the fact that I am the only member without German citizenship, and yet we have never lived in Germany. It was time to do that before my kids are no longer kids (which will be shockingly soon).

Yet the fact that the editor of The Christian Science Monitor will live in Germany for a year does say something important.

The trend is for American newspapers to be scaling back international coverage. Generally speaking, international news doesn’t sell in the United States. And it is fantastically expensive. What papers usually do best is cover their own communities.

But what does the Monitor do best? I would argue that it offers a transformative view of the world itself – that the human story is more interconnected and more hopeful than much media coverage would have us believe. The qualities that drive world events – justice, equality, compassion, trust, honesty – know no borders. To understand the news is to understand how the struggle over these qualities shapes our experience worldwide. That is what news is.

For a news organization tasked with bringing the world closer in profound ways, new possibilities are always emerging. For my part, I hope to share with you insights gained from broadening a sense of home and identity. For the Monitor’s part, I hope we are strengthening a statement that has always been true. The Monitor has long been touted as “an international daily newspaper.” This year, we’ll take a small step toward further proving that, while it is based in Boston, the Monitor is for the world.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What Russian attacks on grain trade mean for world

Russia has launched near-nightly attacks on Ukrainian export facilities since it withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative. Tons of grain have burned and prices have surged, reviving concerns for worsening global food security.

Amid the distinct smell of burnt grain, it is the piles of mangled fragments of Russian missiles that attest to the importance of one family-owned, small-to-midsize Ukrainian grain storage site.

The facility 75 miles southwest of the Black Sea port of Odesa was targeted by Moscow less than a week ago as Russia stepped up its bombardment of Ukraine’s port and agricultural facilities. It was hit before dawn with three rockets, then with two more rockets an hour later.

Warehouses were blasted, machinery melted, and 120 metric tons of dried peas and barley burned.

The United Nations and many African and Middle Eastern nations, especially, depend upon the vast grain harvest in Ukraine, which produces 10% of the world’s wheat and 15% of the world’s corn. U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called on Russia to return to the agreement because of the impact on “vulnerable countries struggling to feed their people.”

“We never expected such things to happen to us,” says Olha Romanova, who built up the Willow Farm facility from her family’s small plot in 1996. “You should count your importance by the number of rockets they send. We can’t fit it into our heads; there is no military logic.”

What Russian attacks on grain trade mean for world

Amid the distinct smell of burnt grain, it is the piles of mangled fragments of Russian missiles that attest to the importance of one family-owned, small-to-midsize Ukrainian grain storage site.

The facility 75 miles southwest of the Black Sea port of Odesa was targeted by Moscow less than a week ago as Russia stepped up its bombardment of Ukraine’s port and agricultural facilities. It was hit before dawn with three rockets, then with two more rockets an hour later.

Warehouses were blasted, machinery melted, and 120 metric tons of dried peas and barley burned.

Beside a wrecked loading platform, two missile tail pieces spill with barley, an incongruent image created by the Russian campaign to crush Ukraine’s grain export capability.

The United Nations and many African and Middle Eastern nations, especially, depend upon the vast grain harvest in Ukraine – it produces 10% of the world’s wheat and 15% of the world’s corn – to feed millions of people.

“We never expected such things to happen to us,” says Olha Romanova, who built up the Willow Farm facility from her family’s small plot in 1996. “You should count your importance by the number of rockets they send. We can’t fit it into our heads; there is no military logic.”

Ms. Romanova says the official Russian justification for the strike was so absurd – that a clandestine drone-making factory was hidden in her storage buildings, in the heart of a rural farming community – that she just cried when she heard it.

Today, workers use shovels to separate burnt barley from clean, drag away destroyed vehicles, and load remaining stocks onto trucks – when they aren’t marveling at the remnants of the Russian missiles that turned their lives upside down. They estimate that only 30% of the facility is repairable.

“The situation is changing every day,” says Ms. Romanova, who notes that the facility will, for the time being, have to “sell from the wheels” – a term that means loading the harvested grains directly onto trucks for transshipment, without storing at all.

And this family business is not alone, as Ukraine struggles to recalibrate its export strategy in the midst of Russian bombardment and a potential blockade.

Since Russia withdrew last week from the Black Sea Grain Initiative – which for one year ensured the safe export of food from Ukraine – it has launched near-nightly waves of missiles and drones against Ukrainian ports and export facilities. On Thursday Ukrainian military officials said a missile fired overnight from a Russian submarine in the Black Sea struck the port in Odesa, killing a port employee.

Ukrainian officials estimate that some 100,000 metric tons of grain (one metric ton is 1,000 kilograms, or 2,200 pounds) have now been destroyed across the Odesa region – including 60,000 metric tons at the Chornomorsk port alone – and the targeting of Black Sea ports and smaller ports on the Danube River has raised doubts about shipping safety.

Grain prices have surged nearly 20% since Russia pulled out of the deal, and U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres called on Russia to return to the agreement because of the impact on “vulnerable countries struggling to feed their people.”

“Some will go hungry; some will starve; many will die as a result of these decisions,” the U.N. aid chief, Martin Griffiths, told the Security Council last week.

Alla Stoianova, the Ukrainian official in charge of agriculture for the Odesa region, says stopping the smooth transfer of grain to export facilities early in the harvest season is Russia’s main aim. Some 2 million metric tons of grain are ready for export, she says, and another 1 million metric tons are “waiting on farms to be loaded.”

Yet Russia appears to be planning more than attacking grain transfer logistics on land. Moscow announced in recent days that it will consider any vessel attempting to reach Ukraine to be a “potential carrier of military-purpose cargoes” – and therefore subject to attack.

The United Kingdom Ministry of Defense reported Wednesday that Russia’s Black Sea fleet had “altered its posture” to blockade Ukraine and to patrol shipping lanes between Odesa and Turkey’s Bosporus.

Ms. Stoianova has the estimated losses of grain and export capacity from each Russian strike at the tip of her tongue. She notes that more than $500 million in Ukrainian state funds have been earmarked to insure ships that export grain, even in the absence of the Black Sea grain deal.

And she suggests an additional security measure.

“We are sure that NATO and the U.S. have the ability to escort ships and protect them” in the Black Sea, she says.

“We definitely received signals of them wanting to help us, but there are some formalities and rules, and players and powers,” says Ms. Stoianova. She says Ukraine also understands that NATO has a “long line” of other priorities, and that Ukraine is not yet an alliance member.

“But the situation with Ukraine now is exceptional and is not the same as in other countries,” she says. “Today we are literally the protection from aggression for all of Europe, so we really hope this exception can be made for Ukraine, because the consequences can be disastrous.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin is convening a summit this week with 21 African heads of state in St. Petersburg (down from 45 at a Russia-Africa summit in 2019 in Sochi), some of whom have complained that Russia’s blockade of Ukraine threatens their food supplies. In his speech to the gathering Thursday, Mr. Putin said Russia – also a big grain exporter, which expects a record harvest this year – can fill any gaps and would provide free grain to at least six African nations.

The Black Sea grain deal was originally negotiated by the U.N. and Turkey to ensure that the most vulnerable nations, such as Somalia, Yemen, Egypt, and Afghanistan, received enough food. Indeed, under the grain deal, the U.N.’s World Food Program had grown by this month to depend upon Ukraine for 80% of its global wheat for distribution, up from 50% in 2021 and 2022, according to U.N. figures.

“We produce five to six times more food than we consume; we will not go hungry, no matter what,” says Ms. Stoianova. “But what it [a stoppage] means for the world is a question of food security. A large number of people of the world are now not receiving our grain.”

Her anger becomes palpable regarding recent Russian strikes that have burned grain supplies at dockside and that she considers cynical.

“Russians don’t need Ukrainians; they need our land and resources,” she argues. “They don’t care about Africans, or other suffering countries. They want control over food security.”

On Monday, the Russian campaign crept closer to NATO member Romania. Drone strikes before dawn on the Reni port, on the Danube River, destroyed an estimated 3,500 metric tons of grain waiting to be loaded.

Reni is one of two Soviet-era ports on the Danube that Ukraine has been expanding in order to ship grain directly to Europe by barge, to bypass the Black Sea. In 2022, it exported 16 million metric tons of grain and has now achieved that same volume in the first seven months of this year.

Targeting that port is considered a sign of Russian resolve to disrupt exports from Ukraine, since it lies just a few hundred yards across the river from Romania.

“No one knows what is next; Russia is trying to press European countries, all our friends, to pressure Ukraine to make compromises,” says Eugene Postovik, an Odesa-based marine and cargo surveyor with Svertilov Marine Consulting.

Immediately after the drone attack on Reni, clients were asking for fresh risk assessments, he says. Romanian President Klaus Iohannis strongly condemned Russian attacks on civilian infrastructure “very close to Romania” and warned of “serious risks” to Black Sea security.

An earlier attack on the Izmail port, also on the Danube, damaged one large crane and hit two storage silos.

Mr. Postovik says that while many people are focused on how many tons of grain are being destroyed in the attacks, a far bigger problem is the damage to port facilities, noting, “It takes one year to rebuild a terminal, to get it to the same capacity.”

There is gratitude for the tough statements against Russia at the U.N., but “they are only complaints. We need solutions,” he says.

Further inland, at Ms. Romanova’s damaged grain storage facility, an air raid siren sounds and 15 or so workers rush to evacuate the site, waiting out the alarm on shaded grass.

“We never did that before,” says Ms. Romanova, of heeding the frequent air raid sirens. “But since we have been given a second chance, now we react to each one.

“This damage we can fix, but the most precious thing that can’t be replaced are human lives.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

Hunter Biden courtroom drama raises stakes for his father

A plea deal over tax and gun charges against Hunter Biden fell apart Wednesday. The courtroom drama heightens the political risk for President Joe Biden and his campaign.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The surprise unraveling of first son Hunter Biden’s plea deal on tax and gun charges Wednesday in a Wilmington, Delaware, courthouse has raised the stakes not only for Mr. Biden but also for his father.

What the Biden family had clearly hoped would be the quiet conclusion of a multiyear legal saga now threatens to become a longer, more complicated ordeal that could overshadow the president’s reelection campaign. And it has given Republicans fresh ammunition as they explore the possibility of an impeachment inquiry.

House Republicans, who labeled the original plea bargain a “sweetheart deal,” have been conducting their own investigations of Mr. Biden, as well as the Department of Justice’s handling of his case. A congressional hearing last week featured testimony from two Internal Revenue Service agents who claimed that Justice officials had impeded their investigation.

“By refusing to accept the plea deal, the judge signaled that there’s more to the story than the Bidens claim,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia, in an email. “But similar to the way that [former President Donald] Trump’s multiple indictments don’t seem to be hurting him among Republicans, it’s hard to imagine that this will matter to Democrats.”

Hunter Biden courtroom drama raises stakes for his father

Wednesday was already going to be a somber day for first son Hunter Biden, as he appeared in federal court to formalize a plea deal over tax and gun charges after a yearslong investigation. In exchange, the president’s son would avoid prison. The deal had elicited cries of favoritism from Republicans.

Then, in a surprise, the agreement fell apart over questions from the judge overseeing the case as to whether it would immunize Mr. Biden from future potential charges, including unregistered foreign lobbying and more tax charges. For now, the president’s son has pleaded not guilty to all existing charges, as lawyers for both sides prepare briefs in anticipation of resumed negotiations.

The drama in a Wilmington, Delaware, courthouse has raised the stakes not only for Hunter Biden but also for his father. What the Biden family had clearly hoped would be the quiet conclusion of a multiyear saga now threatens to become a longer, more complicated ordeal that could overshadow the president’s reelection campaign. And it has given Republicans fresh ammunition as they explore the possibility – for now, still notional – of an impeachment inquiry.

House Republicans, who had labeled the younger Mr. Biden’s original plea bargain a “sweetheart deal,” have been conducting their own investigations of his business dealings, as well as the Department of Justice’s handling of his case. A congressional hearing last week featured testimony from two Internal Revenue Service agents who claimed that Justice officials slow-walked or otherwise impeded their investigation.

“By refusing to accept the plea deal, the judge signaled that there’s more to the story than the Bidens claim,” says Jennifer Lawless, a political scientist at the University of Virginia, in an email. “But similar to the way that [former President Donald] Trump’s multiple indictments don’t seem to be hurting him among Republicans, it’s hard to imagine that this will matter to Democrats.”

Still, she adds, journalists will now ask the president questions about this at every opportunity. And any minute he isn’t talking about economic growth, reproductive rights, and legislative achievements is a minute lost.

At the White House briefing Wednesday, spokesperson Karine Jean-Pierre framed the issue as a family matter and maintained that President Joe Biden has steered clear of involvement in his son’s legal problems.

“The president, the first lady, they love their son, and they support him as he continues to rebuild his life,” Ms. Jean-Pierre said. “This case was handled independently, as all of you know, by the Justice Department under the leadership of a prosecutor appointed by the former president, President Trump.”

Ms. Jean-Pierre was initially alluding to the younger Mr. Biden’s struggles with drug addiction following the 2015 death of his brother, Beau. He has since paid back taxes, plus penalties and interest, for two years in which he failed to file returns. As part of the plea deal that fell apart, Mr. Biden would have avoided being charged for falsely saying he was not a drug user when he purchased a .38-caliber revolver at a Wilmington gun store on Oct. 12, 2018. He agreed to enter a pretrial diversion program under that deal.

Adding to the political firestorm, House Ways and Means Committee Chair Adam Smith moved Tuesday to block the plea deal. The Republican filed a brief urging the judge in Wilmington to consider last week’s testimony from the two IRS investigators claiming that the younger Mr. Biden had received preferential treatment.

President Biden has faced continued allegations that he helped his son in his son’s lucrative international business dealings – trading on the family name – and that the senior Mr. Biden benefited financially. The White House has repeatedly denied such assertions, but has changed its message from the president “never discussed business” with his son to he “was never in business” with his son.

In fact, it was President Trump’s phone call to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in 2019 requesting he “look into” Hunter Biden and his then-vice president father that led to Mr. Trump’s first impeachment.

Now, Mr. Trump faces multiple criminal indictments, including new federal charges expected soon over his alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election result. And, to complicate matters further, he is the odds-on favorite to face President Biden in a 2024 rematch for the presidency.

Republicans are not sitting quietly by. This week, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy said the House was prepared to proceed with an impeachment inquiry into President Biden, following allegations of corruption over his involvement in his son’s business dealings.

The colliding legal and political dramas have transfixed Washington.

“Is it more important to look at criminal conduct by a sitting president or is it more important to look at criminal conduct by ... a son of a sitting president?” Rep. Ken Buck, a Republican from Colorado and former federal prosecutor, said on CNN. “That’s going to be debated in public.”

When asked what he thought, Representative Buck responded, “It’s absolutely Congress’ role to look at possible impeachment, but I also think that if this is just a political game, then we need to make sure the criminal case goes forward.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated.

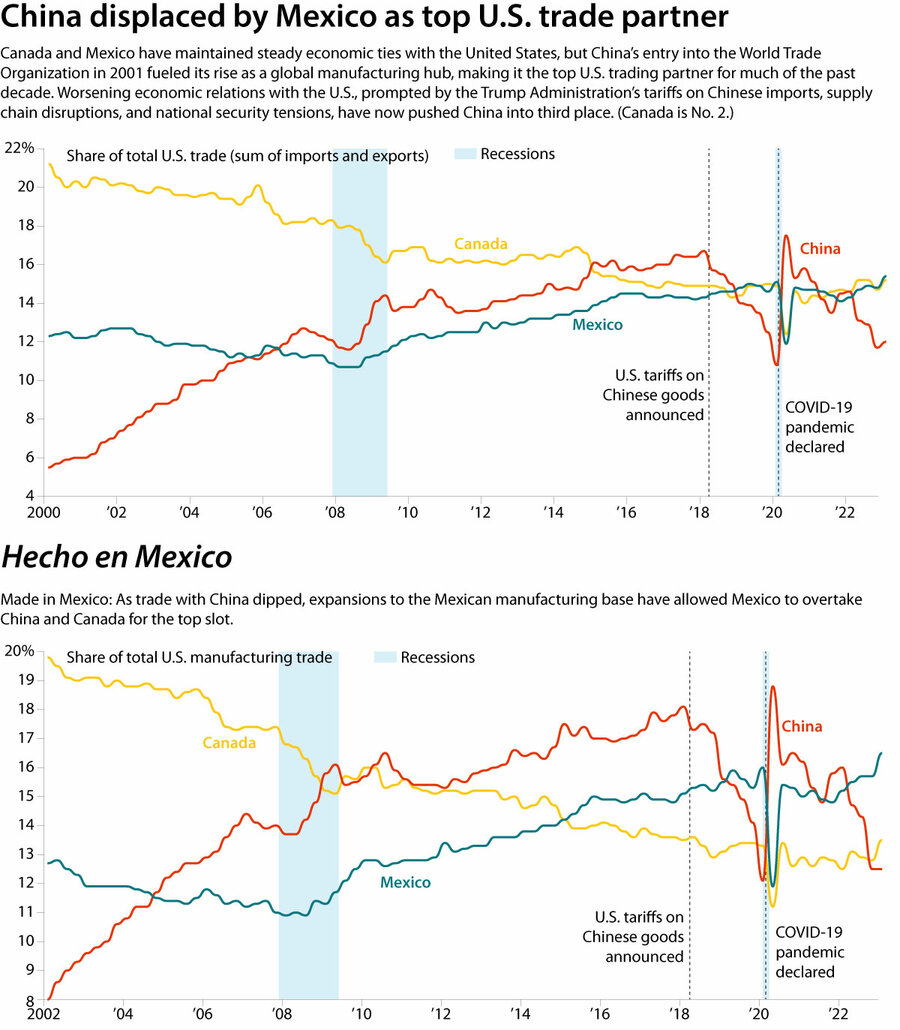

Graphic

In charts: A shift in global trade

For years, the United States and China were growing increasingly intertwined as giants of the world economy. Now, the word “decoupling” may be an exaggeration, but our graphic, by Jacob Turcotte, shows a significant adjustment in trade.

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Patterns

As heat rises, so does pushback on green initiatives

Governments are facing dueling pressures on climate policies: addressing searing new climate challenges responsibly amid a rising “greenlash” against pushing too far, too fast.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Just as almost the whole Northern Hemisphere was baking in record-high temperatures, there are signs that governments are having second thoughts about how much they are prepared to do in order to usher in a low-carbon green economy.

The phenomenon has been dubbed “greenlash.”

An election on the outskirts of London, for example, unexpectedly went to the ruling Conservative Party. The reason: The city’s Labour Party mayor is planning to charge drivers of diesel cars that are more than 20 years old $15 a day to operate in a soon-to-be-expanded ultralow emissions zone.

The result set off political shock waves, shaking a broad consensus among all the major parties in favor of strong climate change policies.

In Europe, the leaders of France and Belgium recently raised the idea of a pause in climate change legislation. The German government has softened the terms of a phaseout of internal combustion vehicles under pressure from the auto industry. It has also faced resistance to plans to phase out gas boilers for home heating without sufficient financial incentive to homeowners.

The United States has been less affected by the trend, a result perhaps of carrots versus sticks. Even climate-skeptic officials have been won over by the hundreds of billions of dollars for clean energy projects that the Inflation Reduction Act contains.

As heat rises, so does pushback on green initiatives

It was a most unlikely setting for a watershed moment in the world’s response to climate change.

Yet a special election in the constituency of Uxbridge and South Ruislip, on the northwest edge of London, has served notice that the arguments around protecting our overheating planet are changing. They are focused less on the reality of global warming and governments’ ambitious commitments to stanch rising temperatures. Instead, there are signs of pushback against the measures needed to deliver on those pledges.

“Greenlash,” the phenomenon is being dubbed.

It is coming largely from the businesses, communities, and individual citizens who stand to be most directly affected by the transition to a greener economy.

But it’s being magnified by world economic conditions – slowing growth, rising fuel costs, and squeezing living standards – caused by the twin shocks of the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

And it’s being amplified by politicians. Not just longstanding opponents of climate action, but also some more mainstream figures concerned about the economic and political consequences of pushing too far, too fast.

That is why the Uxbridge election mattered, not just for leaders in Britain, but also for those in other countries responsible for most of the carbon emissions that fuel global overheating: the 27 members of the European Union, China, and the United States.

Do they stay the course, which will mean finding the funds to cushion those industries and individuals who will lose out financially in a transition to a clean economy? Or do they slow down, pare back, or even jettison key aspects of their climate change policies?

The Uxbridge election provided unexpectedly stark confirmation of a shift that is noticeable in other developed economies.

The ruling Conservative Party won by a whisker by highlighting a single issue: a decision by the Labour Party mayor of London to extend the city’s ultralow emissions zone to the outer suburbs. Drivers of pre-2005 diesel vehicles in the zone will have to pay around $15 a day.

The result set off political shock waves, shaking a broad consensus among all the major parties in favor of strong climate change policies.

Leading Labour figures blamed London’s mayor for the Uxbridge loss. The result bolstered those who want to pull back from the party’s other green pledges, such as an end to further development of Britain’s North Sea oil and gas.

Some Conservative politicians, meanwhile, saw Uxbridge as a template for holding on to other seats at next year’s national election, by taking aim at the Labour Party’s climate policies and rowing back on key aspects of their own, such as an end to sales of new gas and diesel vehicles by 2030.

It’s still unclear whether either party will rewrite, or abandon, its plans to deal with climate change. But the political climate is clearly changing, even though a new scientific analysis this week concluded the current heat wave would have been “virtually impossible” without the effects of “human-induced climate change.”

The politics of climate change are also changing in a number of countries in the EU, which has adopted a range of ambitious climate policies and earmarked some $300 billion in post-pandemic recovery funds for green initiatives.

In an Uxbridge-like jolt, a new farmers party won a provincial election in the Netherlands recently by opposing nitrogen-emission limits on agriculture.

In Germany, the government has softened the terms of a phaseout of internal combustion vehicles under pressure from the auto industry. It has also faced resistance to plans to phase out gas boilers for home heating without sufficient financial incentive to homeowners.

The leaders of both France and Belgium, President Emmanuel Macron and Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, recently raised the idea of a pause in climate change legislation.

And in China, the world’s largest carbon emitter, leader Xi Jinping declared on the heels of last week’s visit by U.S. climate envoy John Kerry that China, alone, would decide the “pathway and means ... tempo and intensity” of its green policies.

Translation: Though Mr. Xi has overseen world-leading investment in electric vehicles, solar panels, and wind power, a slowing economy and the impact of searing heat on the electric grid mean he will continue expanding the use of carbon-intensive coal power.

So does this foreshadow a full-scale retreat from world climate commitments?

Not necessarily, or at least not yet.

There could be a shift toward a more-carrot-than-stick approach, of the sort taken by U.S. President Joe Biden, whose 2022 Inflation Reduction Act offers hundreds of billions of dollars to clean energy projects.

Even that has met resistance – in part, perhaps, because most of the subsidies are intended for rural areas won by Republican candidate Donald Trump in the 2020 election.

But there’s less sign of what might be called Uxbridge anger in the areas being offered this funding, as a recent Washington Post piece explained.

One former Ohio county commissioner, who gave the green light to a major renewable energy project, explained why he’s been urging fellow Republican officials to follow suit.

“We have new parks; the school systems are flourishing with all the additional revenue; the roads are in the best condition they’ve been in,” he said. “I am a die-hard conservative, but I support renewables because they’ve just been amazing for us financially.”

Books

In Zimbabwean language, ‘Animal Farm’ takes on new meaning

Across Africa, English is touted as the language of modernity while African tongues are treated as historical relics. By translating a literary classic into Shona, a group of Zimbabwean authors seeks to change such perceptions.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When novelist Petina Gappah first read “Animal Farm” as a 13-year-old, she was transfixed. Years later, reading it with her teenage son, she connected the cycles of revolution and betrayal with the political turmoil in her own country, Zimbabwe, and decided to translate it into the language Shona.

Ms. Gappah and Tinashe Muchuri, a poet, led a team of Zimbabwean writers to transform “Animal Farm” into “Chimurenga Chemhuka” – literally, “Animal Revolution.”

“We wanted to show that you can read the classics in Shona, and nothing is lost because this is a modern language too,” Ms. Gappah says.

The translation appealed to Mr. Muchuri because author George Orwell’s brand of allegory has parallels in Zimbabwean storytelling. “Our culture often uses animals to tell stories about people and society,” he says.

In “Chimurenga Chemhuka,” Old Major, the boar who inspires the animals of the farm to rebel, speaks in Karanga, the same dialect as Zimbabwe’s current president, Emmerson Mnangagwa. Squealer, the spin doctor, speaks a form of Shona from eastern Zimbabwe that is flecked with English terms, “because this character loves fancy words and spinning stories,” Ms. Gappah says.

Mr. Muchuri says the writers are turning their attention to other translations that will be equally relevant for Zimbabweans – they hope to tackle “Julius Caesar” next.

In Zimbabwean language, ‘Animal Farm’ takes on new meaning

When Zimbabwean novelist Petina Gappah first read George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” as a lonely 13-year-old at boarding school, she was transfixed. The story of a group of animals who overthrow an unjust regime only to be betrayed by their leader “made me sob,” she remembers.

Years later, she revisited the novel as a university student and learned that the book had been written as an allegory for the Russian Revolution. “I respected it on a new level,” she says.

But it was only when she read the book a third time many years later, with her teenage son, that she realized that the book’s cycles of revolution and betrayal were “such a Zimbabwean story.” That thought prompted another: The book should be translated into Shona – one of Zimbabwe’s dominant languages.

Over the next several years, Ms. Gappah and Tinashe Muchuri, a poet, led a team of Zimbabwean writers to transform “Animal Farm” into “Chimurenga Chemhuka” – literally, “Animal Revolution” – which was published earlier this year. The goal, they say, is to reach a new generation of Zimbabwean readers with the classic story, but also to upend the way African languages are often seen in literature.

“Japan developed in Japanese. China developed in Chinese. But there’s a dissonance in Zimbabwe – and a lot of other African countries – where we feel English is the language of modernity and our mother tongue is the language of the ancestors,” Ms. Gappah says. “We wanted to show that you can read the classics in Shona, and nothing is lost because this is a modern language too.”

This is far from the first foreign work of literature to be translated into Shona, of course. When Zimbabwe achieved independence from its brutal white-minority government in 1980, its writers clamored to join “the pan-African intellectual circuit,” says Tinashe Mushakavanhu, a scholar of African and comparative literature at the University of Oxford.

Encouraged by their bookish new head of state, a schoolteacher-turned-revolutionary named Robert Mugabe, Zimbabwean writers began translating works of African literature – like Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s “A Grain of Wheat” – into Shona. “These translation projects were part of a much bigger political project” to open Zimbabwe to the world, Dr. Mushakavanhu says. “It was a way of collapsing borders.”

But as Mr. Mugabe’s politics – like those of porcine dictator Napoleon in “Animal Farm” – grew increasingly paranoid and parochial, the country’s literary space shriveled. Although not specifically harassed and imprisoned in the same way as journalists, fiction writers also fell victim to the country’s increasing isolation – and economic collapse – in the 1990s and early 2000s. By the time Mr. Mugabe entered his third decade in power at the turn of the 21st century, most major Zimbabwean writers were publishing – and often living – outside the country.

Among them was Ms. Gappah, who was working as a lawyer in Geneva when she published her first collection of short stories, “An Elegy for Easterly” (which was later shortlisted, fittingly, for the Orwell Prize).

In 2015, she dashed off a post on Facebook about her idea to translate “Animal Farm” into Shona.

“A group of friends and I thought it would be fun to bring the novel to new readers in all the languages spoken in Zimbabwe,” she wrote. “This is important to us because Zimbabwe has been isolated so much in recent years, and translation is one way to bring other cultures and peoples closer to your own.”

Two dozen writers put their hands up, and the group began experimenting. But ultimately, it was Ms. Gappah and Mr. Muchuri, who writes in Shona, who took over the project.

The translation appealed to him, Mr. Muchuri says, because Orwell’s brand of allegory had so many parallels in Zimbabwean storytelling.

“Our culture often uses animals to tell stories about people and society,” he says. One modern example is writer NoViolet Bulawayo’s 2022 novel “Glory,” an “Animal Farm”-inspired satire about the fall of a dictator named Old Horse – an equine stand-in for Mr. Mugabe. The novel was shortlisted for the 2022 Booker Prize.

To give “Chimurenga Chemhuka” its own Zimbabwean flair, the translators made creative use of Shona dialects. While the book’s text was narrated in a standard form of the language, the characters have different regional accents.

Old Major, the boar whose stirring speech inspires the animals of the farm to rebel against their human master, speaks in Karanga, the same dialect as Zimbabwe’s current president, Emmerson Mnangagwa.

Squealer, the spin doctor who serves as Napoleon’s propaganda minister, speaks a form of Shona from eastern Zimbabwe that is flecked with English terms, “because this character loves fancy words and spinning stories,” Ms. Gappah says. The sheep, meanwhile, speak in slang.

The result, says Dr. Mushakavanhu, is a translation that draws out the book’s dark comedy.

“One of the results of the closing of Zimbabwe in the last 25 years is that our writers have been forced to become political, to always explain the evils of our political system,” he says. “We lost that space to be playful in language and find humor.”

Now that “Chimurenga Chemhuka” is finished, Mr. Muchuri says the writers are turning their attention to other translations that will be equally relevant for Zimbabweans.

“People learn better in their own language, and we want people to know that there is nothing lost or missing when they read in Shona,” he says. “Next, we would like to do ‘Julius Caesar.’”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Local bonds that heal after a war

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For more than a year, warring factions in Yemen have sought to end nearly a decade of conflict. The civilians aren’t waiting. Yesterday 42 community groups issued their own road map for a society built on inclusivity, equality, and rule of law. “Sustainable and lasting peace can only be achieved by welcoming reconciliation through justice,” they declared.

The moral strength of that appeal rests in scores of small-scale projects showing that empathy and compassion nurture peace. “Women and civil society organizations working at the grassroots level are accepted by local communities and enjoy their trust because they are responsive to their needs,” wrote the founder of one local organization.

The war in Yemen severely restricted the ability of civil society groups to work. A truce brokered by the United Nations last year has gradually reopened that space. International development agencies have begun to empower local organizations.

Something similar is starting to happen in Ethiopia, another country that is caught between a stalled peace accord and rebuilding. In that country, youth from warring ethnic groups are gathering in trust-building workshops.

Societies emerging from conflict often need models of courage in forming a lasting peace. In Yemen and Ethiopia, those models are emerging at the grassroots.

Local bonds that heal after a war

For more than a year, warring factions in Yemen and their foreign backers have sought how to end nearly a decade of conflict. The civilians aren’t waiting. Yesterday 42 community groups and professional associations issued their own road map for a society built on inclusivity, equality, and rule of law. “Sustainable and lasting peace can only be achieved by welcoming reconciliation through justice,” they declared.

The moral strength of that appeal rests in the examples set by the coalition, which includes women and youth, educators and health care providers, lawyers and journalists. Through scores of small-scale projects to rebuild communities and livelihoods, the coalition is showing that empathy and compassion nurture peace and dissolve division.

“Women and civil society organizations working at the grassroots level are accepted by local communities and enjoy their trust because they are responsive to their needs,” wrote Kawkab al-Thaibani, founder of the Yemen-based She4Society Initiative, in the online journal Democracy in Exile.

Many of the projects are simple. Most arise from needs compounded by war. Ethar Farea, a young woman in Aden, developed a plan to turn organic waste into fertilizer for farming. “Having such programmes is a glimmer of hope and an opportunity for youth for the desired change,” she told the United Nations Development Program.

Projects like that are gaining new momentum. The war, which erupted between government forces and Iran-backed Houthi rebels in 2014, severely restricted the ability of civil society groups to work. A truce brokered by the U.N. last year has gradually reopened that space. While the two sides attempt to resolve their political and economic disagreements, international development agencies have begun to empower local organizations.

Something similar is starting to happen in Ethiopia, a country that is currently caught between a stalled peace agreement and formal processes of rebuilding. In that country, several smaller factions and a neighboring army were drawn into a two-year conflict between the government and a dissident faction in the northern state of Tigray. The peace agreement called for a national process of reconciliation.

While that has yet to begin, a group called the Tigray Youth Association has begun countering conflict through dialogue with youth from other ethnic groups. With help from the U.N., it held a reconciliation and trust-building workshop in April. The African Union hosted a similar exercise last October. A youth festival in April sponsored by the United States brought 20,000 young people together from around the country.

In Yemen, a potent unifying moment came last month when the country’s under-17 boys’ soccer club made it to the quarterfinals in the AFC U17 Asian Cup. The team’s players came from across the country – and so did the nation’s response. One Yemen coach’s post-tournament reflections carried a larger message. “We are all working hard and hoping that things remain stable,” Miroslav Soukup told Deutsche Welle. “If there can be a more normal football situation, then there is potential. There is a long way to go, but we are taking small steps.”

Societies emerging from conflict often need models of courage in forming a lasting peace. In Yemen and Ethiopia, those models have already started.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What more do I need?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Russ Gerber

Digging deeply into the textbook of Christian Science helps us see more of what we really are as children of God and experience healing.

What more do I need?

Have you ever grappled with a problem and been given advice by someone attempting to help, but then silently dismissed their suggestion? “That’s not what I need,” you tell yourself. “I need something more.”

That’s what I did about a year ago when I was praying for healing of a persistent pain in my lower back. I was intent on finding a solution through my practice of Christian Science by studying its textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy. The spiritual ideas in that book explaining the Science of being had met so many needs in my life and brought spiritual growth and healing. I was sure this time would be no different.

I started reading the chapter titled “Christian Science Practice” but stopped after a few minutes. I felt nothing. At that point I put the book aside and prayed to God with all my heart, “What more do I need?”

A thought occurred to me. It’s an instruction also found in Science and Health: “Read this book from beginning to end. Study it, ponder it” (p. 559). I had studied the book from cover to cover many times. This time I was sure I needed something more.

Then I realized I wasn’t paying attention to the last part of the instruction: “ponder it.” With that in mind, I picked up the book and again started reading. This time I had questions, and I wanted to devote as much time as I could to finding satisfying answers.

The chapter “Christian Science Practice” starts with a story from the New Testament about a meal hosted by a religious leader named Simon for his honored guest, Christ Jesus. I asked myself, “Why did Mrs. Eddy begin the chapter with this story?”

Themes in this story include repentance and reform and how much Jesus valued these stages of growth in Christian character. He saw these traits being expressed by a woman intruding on the dinner – a woman condemned by the community as a sinner.

I continued pondering: Am I overlooking some character flaw in myself? It required a lot of humility to thoroughly examine my thinking and be willing to correct whatever needed correction. My desire was to live in accord with how God, divine Love, created each of us as the spiritual expression of His all-good and all-loving nature.

This meant I needed to do a better job of being patient, charitable, and humble, and of doing good to others, which is how Jesus lived his life. It was a model for living that I needed to live up to more fully. Not in the distant future, but now.

I kept pondering these lessons and endeavoring to replace any unloving traits with greater patience and compassion.

As I continued reading, I came to this: In summing up the example of the woman, Mrs. Eddy explained, “If the Scientist has enough Christly affection to win his own pardon, and such commendation as the Magdalen gained from Jesus, then he is Christian enough to practise scientifically and deal with his patients compassionately; and the result will correspond with the spiritual intent” (p. 365).

My intent had seemed right. I was practicing Christian Science with the intent of being healed. But the reference is to spiritual intent. That implies a higher, unchanging source of intent: the will of God – not something that may or may not come to pass but that which is guaranteed and permanent. And with God as its source, the intent, or will, is invariably good, complete, done. God’s will for His children (you and me) is for us to be Godlike – loving, purposeful, healthy, flawless – just as He created us to be. This is already true about us; it’s how we are made.

This means that no matter how long we’ve held on to character flaws or bad habits, we can let them go because they don’t actually belong to us. God knows and sustains the real selfhood of each of His children, and God is right here every moment to remind us of what does belong to us always.

The repentance and reform that followed helped me to gain rich insights into my actual selfhood as the likeness of God, and to see – and let go of – what is not part of that selfhood. I was a freer and better man as a result.

The next morning brought yet another result. As I stepped out of bed, I was pleasantly surprised to find that all the back pain was gone. Entirely gone.

There’s much to be gained by studying Science and Health. And while you’re studying, take time to ponder. You’ll love the results.

Adapted from an article published in the July 17, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

The story (melting) glaciers tell

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for our “Why We Wrote This” podcast, where we dive deeper into how a Monitor story changed the lives of young girls in Malawi.