- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

How Jaylen Brown wants to turn his money into a bridge

Ken Makin

Ken Makin

Boston Celtics star guard Jaylen Brown has worn the city’s name on his heart for the past seven seasons. Last week, on the heels of securing the biggest contract in NBA history, Mr. Brown wore something new on his heart: a shirt with a word that spoke to what he planned to do with his newfound wealth – “BRIDGE.”

In a news conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, Mr. Brown said he wanted to close the wealth gap and “bring Black Wall Street to Boston.” It was a callback to the prominent Tulsa, Oklahoma, neighborhood, which was violently brought down by white rioters. “Being an athlete, you have a lot of influence in your community, and if you use it responsibly, you can make the world a better place,” Mr. Brown told CBS News.

For years, Mr. Brown has attacked defenses with his athleticism. But his activism has proven to be just as daunting. In 2020, he drove 15 hours to Atlanta, just outside of his hometown in Marietta, Georgia, to lead a Black Lives Matter protest. A few months later, he was one of the leading voices in support of the Milwaukee Bucks’ wildcat strike.

His on-court efforts have placed the Celtics at the cusp of a championship. His off-court efforts are trending in a similar fashion and may soon draw comparisons to the likes of Bill Russell and Jim Brown, who were key figures in the Civil Rights Movement.

Mr. Brown’s $300 million contract can’t cure systemic racism. But imagine if Mr. Brown’s conscientiousness caught on – among not just millionaires, but everyone. The type of community care that sees inequity and dares to change it for the better is indeed the bridge to a better tomorrow.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

How Israel democracy battle is challenging Biden ... and US Jews

U.S.-Israel relations, it has long been said, reflect shared values as well as interests. Now the deep turmoil in Israel over legislation that some fear weakens democracy shows signs of having an impact on both.

The turmoil in Israel, and deep political fissures laid bare by a judicial overhaul that critics say opens the door to autocratic rule, are challenging U.S.-Israeli relations to an unprecedented degree, many longtime experts in the relationship say.

Moreover, the rattling extends from the American Jewish community that has been crucial to Israel’s well-being to the U.S. government. In the weeks leading up to approval of the law, President Joe Biden became increasingly public with his warnings to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to pursue compromise on legislation that was clearly tearing Israeli society apart.

For some, the current questioning of support is bound to have long-lasting impact.

“It’s going to be difficult for Americans of all stripes to absorb the news coming from Israel – the unending demonstrations in the streets, a variety of average Israelis talking about the end of democracy in Israel – without it taking a toll over time,” says Michael Koplow, chief policy officer at the Israel Policy Forum, which supports a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“With it coming in a sustained way and from all sorts of sectors within Israeli society,” he adds, “it’s inevitably going to fundamentally change the way Americans view Israel.”

How Israel democracy battle is challenging Biden ... and US Jews

When the Durham Jewish Community Center contacted Bruce Jentleson weeks ago about speaking to the group in late July, the Duke University Middle East expert accepted – but suggested to his host that few would attend “in the hot, humid North Carolina summer.”

Instead, more than 100 people showed up. The draw, Dr. Jentleson admits, was not so much him, but the fact his talk just happened to fall last Monday, the same day Israel’s Knesset passed with the slimmest of majorities the first piece of a judicial overhaul that has drawn huge protests in Israel for over half a year.

“People are trying to sort out their support for Israel,” says Dr. Jentleson, a former State Department policy specialist on Israeli-Palestinian issues. “Now it’s not just about what the Israeli government is doing to the Palestinians, but to Israel’s society.”

The turmoil in Israel and the deep political fissures laid bare by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s judicial overhaul are challenging U.S.-Israeli relations to an unprecedented degree, many longtime experts in the relationship say.

Moreover, the rattling extends from the American Jewish community and the broader Jewish diaspora – traditionally crucial to Israel’s security and well-being – to the U.S. government. In the weeks leading up to approval of the law, President Joe Biden became increasingly public with his warnings to Mr. Netanyahu to pursue consensus and compromise on legislation that was clearly tearing Israeli society apart.

For some, the current questioning of support is bound to have long-lasting impact.

“It’s going to be difficult for Americans of all stripes to absorb the news coming from Israel – the unending demonstrations in the streets, a variety of average Israelis talking about the end of democracy in Israel – without it taking a toll over time,” says Michael Koplow, chief policy officer at the Israel Policy Forum, a pro-Israel organization that supports a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“With it coming in a sustained way and from all sorts of sectors within Israeli society,” he adds, “it’s inevitably going to fundamentally change the way Americans view Israel.”

The measure passed July 24 was championed by Mr. Netanyahu’s far-right government as a necessary shift of power from an unelected Supreme Court to the elected legislative branch.

But for opponents from a broad spectrum of Israeli society who have protested for more than 30 weeks, the legislation dangerously weakens the check the judiciary has exercised on the legislature in what is effectively a two-branch governing system and opens the door to autocratic rule.

Allegations of interference

Once the overhaul was approved, Mr. Biden limited his response to deeming the one-sided passage “unfortunate.”

But even that measured comment added to the fire of those in the United States – mostly Republican members of Congress and conservative foreign policy analysts – who have condemned the administration’s public warnings on the reforms as interference in Israel’s internal affairs.

“The Biden administration should be very careful not to appear to be interfering in Israel’s internal politics, but it’s getting very close to going over the line, if it hasn’t already,” says James Phillips, a Middle East expert at the Heritage Foundation in Washington.

“I’m skeptical that criticizing directly the Netanyahu government and taking sides in the political controversies inside Israel can do anything other than undermine our U.S. reputation for non-intervention in others’ domestic affairs,” he adds. “You’re not going to fix what’s going on in Israel with a [6,000]-mile-long screwdriver from Washington.”

He's also dubious of what he calls “exaggerated claims” that Israel’s democracy is in peril.

“Some would argue that the majority of the voters and the Knesset should be respected, and that denying them the right to approve this judicial reform is taking away democratic rights as well,” Mr. Phillips says.

Some critics of Mr. Biden’s public pronouncements say they reflect a progressive wing in the Democratic Party that has become increasingly vocal with its criticisms of Israel. They question why the president is zeroing in on Israel, when for example he had nothing to say about French President Emmanuel Macron ramming through an increase in the retirement age despite heavy public opposition and giant protests.

Values, and interests

But other experts and Jewish-American supporters of Israel say the Israel case is different because it calls into question the “shared values” of democratic governance at the core of the bilateral relationship.

“This is not just a policy question as it was in France, this is about the fundamentals of democracy, and it’s not the U.S. saying it but a huge swath of Israeli society saying this is a danger to democratic values,” says Dr. Jentleson. Noting how Mr. Biden has made U.S. support for democracies around the world a clarion call of his presidency, he adds, “I don’t see how he could have just said, ‘This is Israel’s own business.’”

Others say that any weakening of Israel’s democratic checks and balances and an increasingly unencumbered path to unilateral Israeli government actions could eventually impinge on U.S. vital interests in the region.

One key example cited: annexation by Israel of the West Bank. The Israeli Supreme Court has stood in the way of steps that could lead to that action. But the new law could pave the way for far-right ministers in the government to move forward on what would be in blatant opposition to U.S. policy supporting a two-state solution.

As for the notion that the U.S. and Israel steer clear of intervention in the other’s political affairs, Dr. Jentleson says it’s simply false.

“The reality is that we have long been involved in each other’s politics,” he says. He cites President George H.W. Bush cutting off loan guarantees to Israel over illegal settlement construction. Or Mr. Netanyahu’s 2015 speech to Congress condemning the Obama administration’s “very bad [nuclear] deal” with Iran.

Then there was Mr. Netanyahu’s tweet in 2017 endorsing then-President Donald Trump’s border wall with Mexico.

Yet just as Israeli opposition to the judicial overhaul is broad-based, criticisms in the U.S. are not limited to the political left.

“This is not just coming from the AOCs and the Ilhan Omars of Congress,” says Dr. Jentleson, referring to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio Cortez and Representative Omar, two hard-line critics of Israel and its treatment of Palestinians in the occupied territories. “When you have rabbis from the Reform Jewish community issuing a statement saying … the most extreme members of the Israeli government do not represent Jewish values,” he adds, “that tells you this is different.”

Overcoming reluctance

Indeed, one remarkable feature of the broader U.S. response to Israel’s turmoil is how mainstream Jewish organizations long reluctant to involve themselves in Israeli politics have embraced more public profiles.

“As Jewish Americans who care deeply about the security and prosperity and social cohesion of the state of Israel, we may not have a vote but we do have a voice,” says Jason Isaacson, chief policy and political affairs officer at the American Jewish Committee (AJC) in Washington.

Shortly after the July 24 vote, the AJC issued a statement expressing its “profound disappointment” at passage of the law – and warned the judicial overhaul “could weaken Israeli democracy and harm Israel’s founding principles.”

Such a weakening would be a deep concern to Israel’s supporters around the world, Mr. Isaacson says, including President Biden.

“The fact that Joe Biden is a longtime deeply sincere friend of Israel has to be considered when you evaluate how the president and his administration have expressed themselves on this issue,” he says. “The president has been clear that this is a matter for Israelis to resolve, but at the same time all of us – friends of Israel, the Jewish-American community, the Jewish diaspora – have a stake in the preservation of Israel’s democracy and preservation of minority rights.”

Still, Mr. Isaacson says the AJC does not agree with organizations like J Street, a Washington-based pro-Israel and pro-two-state-solution organization, that is calling for action and not just words from the Biden administration in the wake of the Knesset vote.

“That’s not the way friends behave,” he says.

Duke’s Dr. Jentleson cites a range of actions the administration could take to put teeth into its disapproval. Those could include “conditioning” certain parts of the $3.8 billion in annual assistance the U.S. provides, or limiting to core Israeli security matters the use of its Security Council veto.

Others say the U.S. should delay approval of a pending visa waiver program for Israel, something Mr. Netanyahu wants dearly to be able to trumpet.

“I frankly don’t foresee the Biden administration taking any of these steps,” Dr. Jentleson says, “but to me measures like that would be pro-Israel because they might help Israel not go down this dangerous path.”

Others say that despite all the pessimism about Israel’s democracy, they see a ray of hope in the political awakening on Israel’s streets – and in how the U.S. has helped uplift that consciousness.

“Over the past eight months what we’ve witnessed is a legal and democratic consciousness in the public that is growing and growing,” says Masua Sagiv, an Israeli visiting assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law. “I think it will take us into the future in a very different way.”

Washington rushes to put guardrails on AI

With artificial intelligence advancing at lightning speed, many experts, and increasingly policymakers, say that Washington needs to move faster than usual on regulation and oversight.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Washington is increasingly heeding warnings that the emerging powers of artificial intelligence are so consequential that they require an entirely new governance regime – similar to that instituted in response to nuclear weapons.

With AI advancing at an exponential pace, this represents perhaps the fastest-moving scientific challenge that the slow-moving creature of Washington has ever grappled with.

While AI could be tremendously helpful in a number of areas when constructively harnessed, the White House and Congress have taken initial steps to develop guardrails.

One key idea that has gained currency is creating a regulatory agency to oversee the fast-growing field and ensure that the object of protecting humanity is not mixed with the object of making money, as it would be in a private company. Many would also like to hold AI developers liable if their systems are used for nefarious purposes. There’s also a push to require that AI-generated content, such as political advertisements, be clearly identified as such.

A Senate hearing last week underscored the seriousness with which both parties are approaching the issue, putting aside partisan sniping.

“What you see here is not all that common, which is bipartisan unanimity,” said Democratic Sen. Richard Blumenthal during the event.

Washington rushes to put guardrails on AI

Computer science professor Stuart Russell had been thinking about the massive potential benefits as well as the risks of artificial intelligence long before AI became a buzzy acronym with the rise of the ChatGPT app this year.

“It’s as if an alien civilization warned us by email of its impending arrival, and we replied, ‘Humanity is currently out of the office,’” said Professor Russell of the University of California, Berkeley at a congressional hearing last week. But he gave a nod to the growing awareness among the public as well as policymakers in Washington that this emerging technology requires oversight. “Fortunately, humanity is now back in the office and has read the email.”

Of course, it’s a long jump from registering the warning to preparing for the arrival of a potent new force, but waking up to its risks is an important first step. And over the past year, Washington has made initial efforts to size up the challenge and strategize about how to install some guardrails – before AI races past them. However, this represents perhaps the fastest-moving scientific challenge the slow-moving creature of Washington has ever grappled with, requiring it to streamline its typically bureaucratic approach to problem-solving.

“We don’t have a lot of time,” CEO Dario Amodei of Anthropic, a San Francisco-based firm that aims to create “reliable, beneficial” AI systems, told senators last week. “Whatever we do, we have to do it fast.”

The reason for urgency? Experts say that, with AI capable of making advances at an exponential pace, efforts to control how it is used – or to avoid unintended harm to society – may only get harder over time.

As AI-related discussions have been happening around Washington over the past year, several key ideas have gained currency: (1) creating a regulatory agency to oversee the fast-growing field and ensure that human interests are not mixed with profits as they would be in a private company, (2) establishing liability so that AI developers know they will be held responsible if their systems are used for nefarious ends, and (3) requiring transparency in AI models and clear identification of AI-generated materials, such as by a watermark or a red frame around a political ad.

An active Congress and White House

Over the past several months, more than 20 bills have been introduced in the House and Senate dealing with various aspects of AI – from requiring the government to conduct risk assessments and develop a public health preparedness strategy, to establishing a bipartisan national commission to make recommendations.

Last week’s hearing was a sign that the lawmakers are trying to move forward, with stepped-up efforts to educate themselves as they consider potential measures.

The Biden administration, for its part, recently welcomed seven AI companies to announce a pact committing themselves to internal and external testing of their models prior to publicly releasing them. Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI (the creator of ChatGPT), as well as Mr. Amodei’s company, Anthropic, and another startup, Inflection, were part of the voluntary agreement.

The pact, which focused on building safety, security, and trust, was hailed as an important milestone, following on the White House’s Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights last fall and an AI risk management framework released in January by the Commerce Department’s National Institute of Standards and Technology.

However, some said the new pact was too vague and lagged efforts elsewhere around the world, from the European Union to China. Experts say that a more robust framework is needed, with the teeth to enforce it – ideally by a new federal agency that would be able to respond and adapt to emerging challenges more quickly than, say, Congress.

While many see the potential for AI to greatly benefit humanity, the technology raises grave concerns about everything from data privacy and election integrity to autonomous weapons and new biological threats. It could also reinforce or exacerbate societal inequities – a concern already raised, for example, regarding the consequences of facial recognition systems being less accurate among people of color.

Tristan Harris and Aza Raskin, who were featured in “The Social Dilemma” documentary warning of the dangers of social media, have described the latest chapter of AI development as a threat to humanity on par with the evolution of nuclear weapons – but worse.

“Nukes don’t make stronger nukes, but AI makes stronger AI,” said Mr. Raskin in a March talk the pair gave to more than 100 leaders in fields ranging from finance to government.

That means that as AI learns more, it can apply the gains across different fields, added Mr. Harris, a former design ethicist at Google. “It’s like an arms race to strengthen every other arms race,” he said, urging leaders to realize the responsibility they have to institute new systems for containing the new technology, just as the world did in its attempt to rein in nuclear proliferation and avert nuclear war.

It’s not just them. Recently, more than 250 AI experts, including Professor Russell, signed a statement saying that mitigating the risk of extinction from AI should be as high a priority as addressing the risk of pandemics and nuclear weapons.

Though there are many potentially constructive uses of AI, it is likely to be a disruptive force in society, even without any Hollywood-style plots about sentient machines intentionally attacking humans.

Bipartisan cooperation

So far, there appears to be bipartisan consensus to act on AI, removing one of the major obstacles to Washington policymaking.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, a New York Democrat, described the Chinese Communist Party’s release this spring of its approach to regulating AI as “a wake-up call” to the United States. For months, he has been discussing and refining ideas for how America could take the global lead on AI innovation and shape the rules of the road.

“We must approach AI with the urgency and humility it deserves,” said Mr. Schumer in a statement outlining his SAFE Innovation Framework, noting that he was encouraging bipartisan policy work and legislation across numerous committees.

As part of that, he is convening a series of nine bipartisan forums for all senators to get up to speed on various aspects of AI, starting with three this summer on AI’s current capabilities, future frontier, and U.S. defense and intelligence capabilities in the field vis-à-vis America’s adversaries.

Similarly, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy has said that all members of the House Intelligence Committee would take AI courses resembling those provided to military generals. And the congressional hearing last week, which featured AI “godfather” Yoshua Bengio of the University of Montreal as well as Professor Russell and Mr. Amodei, was marked by an unusual level of bipartisan comity.

“What you see here is not all that common, which is bipartisan unanimity,” said Chair Richard Blumenthal, a Democrat and former attorney general of Connecticut, who oversaw a serious, substantive discussion for more than two and a half hours before a packed hearing room.

“There has to be a cop on the beat,” he said. “That cop on the beat, in the AI context, has to be not only enforcing rules but also, as I said at the very beginning, incentivizing innovation – and sometimes funding it – to provide the air bags and seat belts and the crash-proof kinds of safety measures that we have in the automobile industry.”

Lessons from social media policy

Another shared view across Washington is that it needs to apply the lessons learned from not dealing sooner and more decisively with social media platforms.

“We can’t repeat the mistakes we made on social media, which was to delay and disregard the dangers,” said Mr. Blumenthal. The Connecticut senator, along with the top Republican on the subcommittee, Sen. Josh Hawley of Missouri, has co-sponsored legislation to prevent AI companies from claiming immunity for third-party content – as social media companies have done – under a telecommunications law known as Section 230.

Senator Hawley, a longtime critic of Big Tech, commended his Democratic counterpart for putting together such substantive hearings but expressed skepticism given legislators’ inability to rein in the sector’s social media regime – and the fact that many of the key players are the same now, including Google, which owns YouTube, and Meta, which owns Facebook.

“Will Congress actually do anything?” asked Senator Hawley, who said his priorities were protecting workers, kids, and consumers – as well as national security. “We’ve had a lot of talk, but now is the time for action.”

Unused French churches find new purposes

France has too many empty church buildings. No one wants to tear them down, but how do towns find new purposes for them while navigating sensitivities about those new roles?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

French municipalities own more than 42,000 churches and Catholic dioceses around 2,500. But heritage experts told the French Senate this month that between 2,500 and 5,000 churches were at risk of being torn down by 2030.

To prevent that, from Nantes to Angers, Rouen to Caen, some of France’s most historic religious establishments are being transformed into concert venues, hotels, and nightclubs.

For many, the transformations are seen as a blessing – a way to save France’s rich religious heritage. For others, it’s sacrilegious. But fewer French are attending church, and even fewer are opening their pocketbooks to save the structures. So city and religious officials are left with few choices: transform their dying churches or say goodbye to a piece of history. How do they decide which path to take?

“The French are very attached to their local bell tower, but how far are they willing to go to save it?” says Mathieu Lours, a historian of religious architecture and heritage. “Some people might not like the idea of transformation, but if no one invests in church maintenance, it will be torn down. We need to find uses for churches that respect the dignity and memory of the place, and create bonds in the community.”

Unused French churches find new purposes

An early morning haze streams in through the stained-glass windows of the Martray Chapel, basking the room in pastel yellow and green. Camille May walks through a maze of metal shelving, spraying nearly 100 cinder blocks of budding shiitake mushrooms with water.

Every few minutes he stops, takes out a carving knife, and cuts a flat-topped pearl from what looks like a giant chocolate brownie.

“See? This one is ready,” says Mr. May, holding the bite-sized treat up to the light before placing it in a plastic basket. By the end of the week, Mr. May and his business partner, Romain Redais, will have collected 70 to 100 kilograms (154 to 220 pounds) of mushrooms, destined for local restaurants and farmers' markets.

While a church is perhaps an unlikely setting for a mushroom harvest, the conditions are perfect: warm and humid, with no major temperature variations. Since 2020, Le Champignon Urbain has been operating here, after winning a competition organized by Nantes City Hall in its search for a way to save the long abandoned 19th-century chapel.

Le Champignon Urbain is one of a growing number of projects breathing new life into churches across France that would otherwise fall into ruin. From Nantes to Angers, Rouen to Caen, some of France’s most historic religious establishments are being transformed into concert venues, hotels, and nightclubs.

For many, the transformations are seen as a blessing – a way to save France’s rich religious heritage. For others, they are sacrilegious. But fewer French are attending church and even fewer are opening their pocketbooks to save them. With thousands of churches across France at risk of ruin due to a lack of maintenance, both city and religious officials are left with few choices: transform their dying churches or say goodbye to a piece of history.

“The French are very attached to their local bell tower, but how far are they willing to go to save it?” says Mathieu Lours, a historian of religious architecture and heritage. “Some people might not like the idea of transformation, but if no-one invests in church maintenance, it will be torn down. We need to find uses for churches that respect the dignity and memory of the place, and create bonds in the community.”

Maintaining churches – and their spirit

France has a unique relationship with its churches that dates back to the French Revolution. The “Reign of Terror,” which began in 1793, led to the abolition of the Roman Catholic monarchy and a nationalization of church property. A century later in 1905, the separation of church and state was enshrined into law. Churches built before that date were put into the hands of city halls; those built later were to be run by the church authorities.

Now, French municipalities own more than 42,000 churches and Catholic dioceses around 2,500.

Around 15,000 of those are classed as historical monuments and qualify for government aid. But for the rest, it’s up to local city halls and dioceses to find the funding to maintain electricity, plumbing, and the iconic bell towers. The cost of renovations can reach into the millions, putting pressure on even the most forgiving budgets. Heritage experts told the French Senate this month that between 2,500 and 5,000 churches were at risk of being torn down by 2030.

That’s precisely what local mayor Patrice Boudignat was trying to avoid when his town chapel in Melz-sur-Seine, outside Paris, fell into disrepair in 2012. The roof was in terrible shape and the Diocese of Meaux, which owned the Blunay Chapel, didn’t have the means to fix it.

“My grandfather helped transform the chapel from a former barn [in 1952] and it was important for me to save it,” says Mr. Boudignat, who has since left office and works as a mustard producer. “We needed to find a way to maintain it without destroying its spirit.”

The diocese agreed to deconsecrate the chapel by official decree, remove all religious insignia, and sell it back to the town for a symbolic one euro. The town hall fixed the roof and transformed the chapel into a cultural center, which now hosts a handful of events each year.

Mr. Boudignat says some residents were shocked to lose the chapel’s original function, but historically, such transformations are nothing new. The French Revolution saw churches converted into storage warehouses and even stables, and in 1958 France’s culture minister, André Malraux, famously bought the Saint-Frambourg Chapel in Senlis, north of Paris, for a symbolic one franc. He offered it to renowned Hungarian pianist György Cziffra, who later turned it into a concert hall and arts foundation.

Four years later, Mr. Malraux passed a law to further protect France’s architectural heritage. Now, the current government appears committed to continuing that tradition.

“We need to work together to preserve and transmit our heritage from generation to generation,” said Rima Abdul Malak, France’s minister of culture, during the National Heritage Fund’s Prix Sésame awards ceremony last month, which recognized 11 church reuse and repurposing projects. “Reuse projects don’t just restore bricks. They restore life, history, our collective stories.”

Scandalous or special?

Still, church repurposing projects are a lengthy process. Once a church has been deconsecrated, applications to use the building are solicited, and both city hall and the local Catholic diocese must give their approval to the winning project before architects can launch into costly and sometimes complicated renovations. According to France’s Observatory for Religious Heritage, 300 churches have been or are in the process of being repurposed, with half centered around housing projects and the rest dedicated to community-service initiatives.

The majority go forward in larger cities without a hitch, where their new usage is less conspicuous. But some transformations are a hard sell, especially for religious members of the community.

Edouard de Lamaze, president of the Observatory for Religious Heritage, recalls a woman calling the transformation of a church in Angers into a nightclub “scandalous,” and a church-turned-hotel in Nantes has created some unease. The 19th-century Petite-Sagesse Chapel, now the four-star Sozo Hotel, features original stained-glass windows and archways in several of its 24 rooms.

“I’m religious so I don’t think I could sleep in a hotel with God looking over my head,” says Nantes resident Mino Ranaivo, while out with co-workers in a nearby restaurant. “I don’t think a church should serve any other purpose than being a church. Transforming it is no better than destroying it, because that transformation destroys it in a way, in the end.”

But Cassandre Blanquart, the hotel’s director, says her customers know what they’re getting when they book a room there, and do so in part for the novelty. Others say the French should reconsider what is and isn’t acceptable inside a church.

“People need to separate religion from heritage, to be open to new possibilities,” says Mr. de Lamaze. “It shouldn’t be about this or that project. It’s about saving our architectural history.”

Part of that, say observers, is getting communities to invest in their local heritage. While the French were extremely generous after the Notre Dame cathedral caught fire in 2019 – donating nearly $1 billion to reconstruction efforts – they’ve been less so with their local churches.

In the meantime, church transformations can be part of the solution. Already, such projects are picking up steam – the Observatory for Religious Heritage lists a half-dozen per month, with 87 in 2022. The goal, for both heritage experts and the community alike, is to create something unique that also retains a church’s original essence.

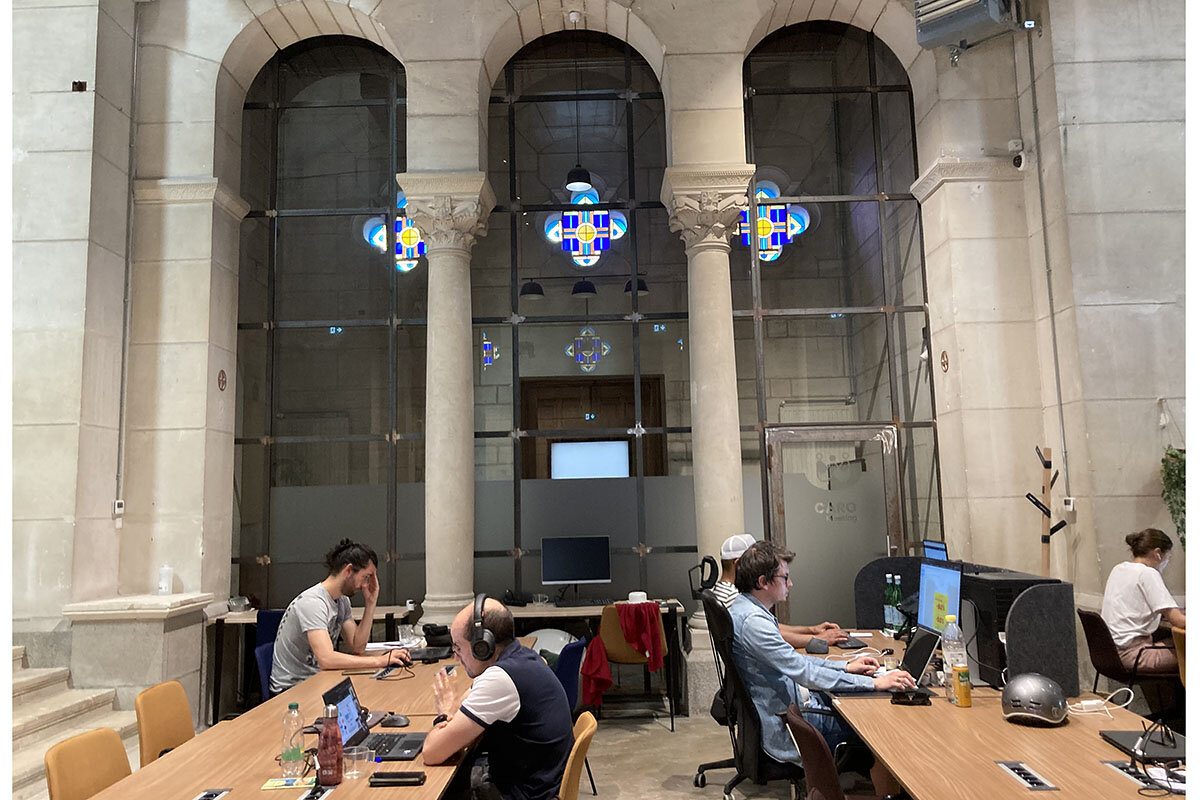

“As soon as I entered this space, I said to myself, ‘This is it.’ It had such a good energy,” says Valérie Frèrejouand, a professional coach who rents a desk at W’in Coworking in the now deconsecrated Marie-Réparatrice Chapel in central Nantes. “Because this is a former church, there is a special light that comes through the windows here and a sense of calm. That energy never goes away.”

Books

Author David Joy talks about race, history in the South

A novelist with deep regard for his fellow North Carolinians delivers a clear-eyed critique of the blindspots of the South – both past and present.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Noah Davis Contributor

Novelist David Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, he overturns preconceived notions of life in the mountains.

In his latest book, “Those We Thought We Knew,” Mr. Joy weaves a tale of a young Black artist returning to her ancestral town in the mountains of western North Carolina and the subsequent arrival of a Ku Klux Klan member who is found passed out in his car. The police find not only evidence of his klan ties but also a notebook with the names and phone numbers of county officials.

Mr. Joy spoke with Monitor contributor Noah Davis about his family’s legacy in North Carolina and about the beauty of the noir genre: “Everything has been whittled down to its most essential. The masks are pulled back,” Mr. Joy says. “Creating a story that strips a time and a place and a people to its bones allows the reader to see it for what it truly is.”

Author David Joy talks about race, history in the South

In his unflinching and timely novel “Those We Thought We Knew,” author David Joy weaves two storylines: the return of Toya Gardner, a young Black artist from Atlanta, to her ancestral home in the North Carolina mountains, and the subsequent arrival of a high-ranking member of the Ku Klux Klan. The man, passed out in his car from inebriation, is discovered by local deputies. Also inside the car is an incriminating klan robe and a notebook filled with county officials’ names and phone numbers. A still-standing Confederate monument at the town’s center sets the stage on which the community will fracture. Unspoken sentiments are suddenly shouted, and shrouded fears and hate come into the light. Mr. Joy has mastered the high-stakes, page-turning Appalachian-noir style, and through this lens, the preconceived notions of life in the mountains are overturned. He spoke recently with the Monitor about North Carolina and the stories that must be told – the same stories that were purposefully hidden.

All five of your novels are set in the mountains of western North Carolina. It’s easy to see how much you admire the beauty and people of that place through your attentive sentences. What does it mean to love and critique a place at the same time?

I think what you’re getting at is what the [rock band] Drive-By Truckers referred to as the “duality of the southern thing.” I speak proudly about being a 12th-generation North Carolinian. My first ancestor comes into what becomes Bertie County in the late 1600s. But the truth is that you can’t make that sort of statement without acknowledging and accepting the horribleness that so much of that history entails. There’s this balancing act of being tied to a place and a people with that sort of past. So to slightly alter something James Baldwin said, “I love [the American South] more than any other [place] in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

Can you talk about what makes the noir genre a compelling style to examine the complex issues around race and history?

I was on a panel with [crime novelist] Megan Abbott once at a festival in Vincennes, [France,] and she said, “Noir lends itself to the social novel.” Everything has been whittled down to its most essential. The masks are pulled back. Creating a story that strips a time and a place and a people to its bones allows the reader to see it for what it truly is. As a country, we’ve reached a place that offers little space for civil discourse. Art allows for that space. It allows for us to be made uncomfortable, to sit with ideas that challenge us, and to do so without choosing a side, without consequence.

This is a novel of questioning and upending expectations. How much was this book an act of discovery for you about the people and place of your home?

I don’t think I consider anything about this book an act of discovery. When you’re dealing with matters of white supremacy, and particularly dealing with Black suffering and trauma and death at the hands of that institution, one of the hardest things to stomach is the cyclical nature of it all. America is stuck in a feedback loop. And the sad truth is that in 2023, we know the defect in the code, and yet we continue to do nothing about it. Take that a step further, and I think that Americans, and particularly white Americans, have a false belief that if we don’t talk about it, it will just go away. We refuse to have the hard conversations. We refuse to address the defect. This book was an attempt at forcing characters into those conversations.

Because of those upended expectations, the reveal leaves the reader feeling unstable. But you’re still able to conclude with a moment of hopeful certainty. Why is that important to you?

There’s a scene in the novel where the grandmother, Vess, is in the garden with her granddaughter, Toya, and the old woman is humming a song while she ties up rows of beans. Toya recognizes the song and pulls it up on her cellphone to play it. The song is Nina Simone’s “Ain’t Got No, I Got Life.” To anyone who knows that tune, it begins as this sort of mournful elegy. But Vess notes that what she’s always loved is the turn, the moment when that lament of all that’s been stolen shifts into a celebration of what cannot be taken away. I wanted the ending of this novel to mirror that arc. Without that shift, we’re left standing in the same place we started. What moves the foot forward is hope.

Difference-maker

How ‘old lady’ swimmers clean up Cape Cod ponds

The goal, says the founder of Old Ladies Against Underwater Garbage, is to show that older women, working as a team, can do a lot more than people might think. The experience, participants say, is one of reverence.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The pond is silent – until the first cry: “Found something!” A septuagenarian swimmer ducks into the water. She emerges, fist first, clutching a pair of bright-blue children’s swimming goggles. These are passed to a kayaker, who waggles them overhead, like a prize, before stowing them in a laundry basket for safekeeping.

Over the next hour, the team of 15 – all over age 65, all women – hunts for trash across Mares Pond, a 28-acre kettle hole near Falmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod.

They turn up wooden planks, silty beer cans, a plastic container lid, a mud-caked fishing rod, and a cement block. The day’s pièce de résistance, though, is a 12-foot segment of aluminum flashing. It requires the combined efforts of several divers to hoist on the back of a kayak.

These are the Old Ladies Against Underwater Garbage. Since 2017, the group has removed trash, by hand, from ponds across Cape Cod.

Ostensibly, the group’s primary goal is conservation. But this isn’t all the group is about. As founder Susan Baur puts it: “The litter is the tip of the iceberg.”

“Over 65, if you’re healthy enough to do what we’re doing, it is the age of gratitude,” Dr. Baur says. “You are so grateful that you can still do this. You’re just grateful anyway, grateful for the trees and grateful for clean water.”

How ‘old lady’ swimmers clean up Cape Cod ponds

The pond is silent – until the first cry: “Found something!” A septuagenarian swimmer ducks into the water. She emerges, fist first, clutching a pair of bright-blue children’s swimming goggles. These are passed to a kayaker, who waggles them overhead, like a prize, before stowing them in a laundry basket for safekeeping.

Over the next hour, on a cloudy Saturday morning in July, the team of 15 – all over age 65, all women – hunts for trash across Mares Pond, a 28-acre kettle hole near Falmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod, at depths of up to 8 feet.

They turn up wooden planks, silty beer cans, a plastic container lid, a mud-caked fishing rod, a cement block, and countless other bits of garbage. The day’s pièce de résistance, though, is a 12-foot segment of aluminum flashing. It requires the combined efforts of several divers to hoist on the back of a kayak.

When the team returns to shore, they are smiling and laughing. They crack jokes about the dive and their haul. “We didn’t even know what it was,” giggles one swimmer, referencing the blueberry-cheesecake-flavored electronic cigarette they found. “We have to ask a young person.”

These are the Old Ladies Against Underwater Garbage (OLAUG). Since 2017, the group – which accepts only older women as members – has removed trash, by hand, from ponds across Cape Cod.

Ostensibly, the group’s primary goal is conservation: It aims to keep the ponds pure for the benefit of both the ecosystem – which includes everything from turtles and herons to grasses and microbes – and its human visitors. But this isn’t all the group is about. As founder Susan Baur, a retired psychologist, puts it: “The litter is the tip of the iceberg.”

Although removing trash is itself valuable work, the women have found another sense of value in the experience of entering, restoring, and then departing a pond. But it’s not exactly easy to put into words.

“I call it the wonderland effect,” Dr. Baur says.

“For most of your life, you have some idea of what you’re doing. You go to a store. ... Cars drive on roads – you know what to expect,” she says. “When you are underwater, it’s like flying. You’re in a different world. And you’re in a world that, in fact, is not an empty bowl of water, [that] is an entire ecosystem which is self-sustaining. Everything fits together.”

The group’s existence is owed to a moment of spontaneity by Dr. Baur. A lifelong nature enthusiast, she had begun swimming in ponds on the cape as a safer alternative to the ocean. However, she found that she “didn’t like them at all.” Between mud, darkness, and snapping turtles, the world of the pond was at first one of anxiety for her.

The only way she could keep her courage up was to rely on markers: “I’d swim to the golf ball, and then swim to the drowned tree, and then swim to the beer can. I love beer cans – they’re easy to spot.”

Eventually, Dr. Baur realized she didn’t need the markers anymore – and that they were multiplying. In 2017, on a whim, she rounded up two friends and approached a stranger with a kayak, and together they cleared “half a bushel” of litter from a pond.

“We thought that was fabulous,” Dr. Baur says. (Today, OLAUG wouldn’t bother with a pond with so little trash, she adds.)

In 2019, after Dr. Baur moved to Falmouth, she and her friends dove for trash in a few more ponds. It was during the pandemic, however, that things took off. “It just bloomed,” Dr. Baur says. “Nobody was doing anything but meeting outside. So my entire social life was diving for garbage and walking the dog.”

Peter Donahue is the treasurer of the association for Jenkins Pond, to which OLAUG has now made several visits. “I think they’re incredible,” he says. “They’re very professional. They’re serious about their work, but at the same time, they have lots of fun.”

The cleanups, he adds, have doubled as community events. Dozens of people come out to watch the swimmers work. “What they provide is a tremendous service that any pond would benefit from,” Mr. Donahue says. “And not just from the physical aspect of it, but the community aspect of it, because of their joy and their energy in what they do, and their belief in what they’re doing.”

Like Dr. Baur, the other swimmers have found a sense of wonder in the pond cleanups. “We literally immerse ourselves,” says Robin Melavalin, who was one of the group’s first members. “And it’s a completely different world under the surface. You see fish of all different sizes. You see a bunch of turtles. It’s beautiful. It’s all underwater miracles.”

OLAUG’s efforts began to garner attention. Local news organizations – the Cape Cod Times, then CBS Boston, then NPR on Cape Cod – picked up the story. And with the publicity came a bevy of outsider opinions on the group’s work.

Many expressed their gratitude, but a sizable contingent criticized the group’s name – that they referred to themselves as “old ladies.”

“You should call yourselves the Lovely Ladies Against Underwater Garbage, or the Mermaids Against Glitter Litter,” Dr. Baur, smirking, recalls being told. Others said she should open the group to all ages, to men.

Although she admits that it wasn’t initially a conscious choice, she now believes that the “old lady” identity is a crucial part of what the group is about.

“Over 65, if you’re healthy enough to do what we’re doing, it is the age of gratitude,” Dr. Baur says. “You are so grateful that you can still do this. You’re just grateful anyway, grateful for the trees and grateful for clean water.”

The result, Dr. Baur says, is an environment free of competition, focused on cultivating respect for the pond. “It’s more reverential.”

Dr. Baur notes that “women over 65 tend to feel the constriction of aging.” They lose power and social standing, she says. Part of the goal of OLAUG is to demonstrate that older women, working as a team, can do a lot more than people might think.

Criticism aside, the most common response was one of inspiration: in Dr. Baur’s words, “I want to join you.”

As the group added more like-minded women to its ranks, it also began to take a more systematic approach to cleanups. Rather than just showing up at a pond, OLAUG developed relationships with local pond associations, which supply it with extra kayaks.

In late June, the group held its first “tryouts.” The event was open to any woman over age 65 who identifies with the adventurous spirit of the group. Rather than being a competition, the tryouts ensured that the new recruits could comfortably swim in a pond, dive down, and lug out tires, hunks of wood, and whatever else they found.

The team added 15 new “old ladies,” more than tripling in size. “I have to learn to do spreadsheets,” Dr. Baur says with a sigh.

The cleanup at Mares Pond was the first outing for the new recruits.

Julia Benz, another longtime member and OLAUG’s resident swimming expert, says that the veterans supported the newbies when they struggled. “We had a person today who was ready to give up. We kind of talked her down,” she says. “We’re not looking for the fastest, the best. We’re looking for people who can share each other’s strength to make a good team.”

One of the new members, Maggie Megaw, had a “fantastic” time. “It’s kind of meditative, really, to be swimming with the fish, the turtles and looking at the aquatic plants,” she says.

As the adrenaline of the dive dwindles, the team enjoys Mares Pond-shaped sugar cookies and the newbies receive their very own neon-orange beanies emblazoned “OLAUG.” Their faces spell their glee.

To Dr. Baur, the new swimmers’ excitement makes perfect sense. “They come up and they have just swum farther than they’ve ever swum. They’ve lifted more than they’ve ever lifted. They’ve seen stuff that they’ve never seen. And they’ve done good,” she says. “They come back with their hearts beating.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

The right armor for African democracy

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

A military coup in Niger last week – the 10th attempted in Africa since 2020 and the seventh to succeed – has brought swift reprisals from other countries that underscore impatience with what appears to be a backsliding of democracy on the continent. If or when the rebellious generals in Niger back down, however, their decision may be influenced more by Africa’s changing mental atmosphere than by military might or diplomatic isolation.

Published just days before the coup in Niger, a United Nations study of causes and responses to unconstitutional power grabs based on interviews with 8,000 people across Africa found “in a compelling manner that tolerance for ongoing inequality, government under-performance and elite self-enrichment is sharply waning across the continent.”

Another coup notwithstanding, Africa’s democratic future rests on the highest qualities of governance that its citizens increasingly seek.

The right armor for African democracy

A military coup in Niger last week – the 10th attempted in Africa since 2020 and the seventh to succeed – has brought swift reprisals. The European Union suspended financial aid and security cooperation to the West African country. Neighboring leaders yesterday threatened military intervention unless the junta restores the democratic government within a week.

Those responses underscore how African and international leaders have become increasingly impatient with what appears to be a backsliding of democracy on the continent. If or when the rebellious generals in Niger back down, however, their decision may be influenced more by Africa’s changing mental atmosphere than by military might or diplomatic isolation.

Published just days before the coup in Niger, a United Nations study of causes and responses to unconstitutional power grabs based on interviews with 8,000 people across Africa found “in a compelling manner that tolerance for ongoing inequality, government under-performance and elite self-enrichment is sharply waning across the continent.”

The study found that poor governance – measured by high levels of corruption, weak security, and uneven economic opportunity – elevates the risk that governments may be overthrown. Only 11% of the Africans surveyed expressed a preference for nondemocratic forms of rule. Inclusive development, particularly for women and youth, the study found, “is prevention, and prevention means peace.”

One country that may be starting to model that route toward stability is Somalia. It fell into dysfunction following the collapse of its long-ruling military regime in 1991 and has seen dozens of failed attempts at restoring the rule of law ever since. In the absence of a strong, central government, the Islamist extremist group Al Shabab extended its control over large parts of the country partly by setting up its own courts to give people access to justice.

Now, a new central government is trying to rebuild democratic institutions, starting with the judiciary. In early July, the country opened its first anti-corruption trial in decades against four top government officials. To boost transparency, the proceedings are televised. The trial follows the adoption of a package of new anti-corruption measures signed into law earlier this year. And those reforms coincide with electoral reforms that will base future elections on the votes of individuals rather than clan elders.

These are fledgling steps, but they mark an attempt to build a more inclusive society based on equality and the rule of law. “We cannot forget the painful past but we can forgive,” Somali President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud said during his swearing-in last year. “We do not need grudges. No avenging.”

For the international community, Niger was seen as a last bulwark against the spread of Islamic extremism across West Africa. Both France and the United States have forces stationed there. As much as the coup poses a challenge for African leaders defending democracy, it offers the international community a nudge for rethinking its security priorities. As the think tank Responsible Statecraft noted last year following a coup in Niger’s neighbor Burkina Faso, outside governments should help African leaders “concentrate on helping civilians.”

Another coup notwithstanding, Africa’s democratic future rests on the highest qualities of governance that its citizens increasingly seek.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Lifting up relationships

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Considering others the way God sees them opens the door to reconciliation and harmony, as a woman experienced after a rocky start with her college roommates.

Lifting up relationships

Good relationships are of interest to most of us. When they are supportive and uplifting, that’s great. But sometimes they seem to be less supportive than hoped for or even pulling us down, and that’s not so great.

I read in the news the other day about a country whose predominant alliance with another country is based on a common enemy, rather than a mutual appreciation of higher values, such as freedom. It got me thinking more about how relationships can be lifted up to bless everyone in a common good.

So if we feel the need for elevating our relationships, where can we begin? One place to start is with the universal truths of the Bible, which exclude no one. The Bible is filled with stories that illustrate God’s ever-present help and care when things are less than peaceful between individuals.

One example is the story of twin brothers Jacob and Esau, whose relationship hit rock bottom. Jacob, the younger of the two, deceived his father in order to get his blessing, which according to custom should have gone to Esau. He then found himself fleeing from Esau’s raging determination to kill him.

Although there is no way to really know what the brothers were thinking through all the many years of their estrangement, Jacob was a praying man who knew the importance of obedience to God. One night Jacob had a mighty battle within, in which he was so changed that he took on a new name.

Following this experience, Jacob and Esau met and reconciled. As The Voice renders it, Jacob said to Esau, “Seeing your face again is like seeing the face of God, so graciously and warmly have you welcomed me” (Genesis 33:10).

“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” – the textbook of Christian Science, written by Mary Baker Eddy – lends spiritual understanding of what Jacob won through his battle within: “The result of Jacob’s struggle thus appeared. He had conquered material error with the understanding of Spirit and of spiritual power. This changed the man.... He was to become the father of those, who through earnest striving followed his demonstration of the power of Spirit over the material senses; ...” (p. 309).

The teachings of Christian Science honor the biblical name Spirit as a synonym for God, the sole source of everyone’s identity. Made in God’s likeness, this identity is entirely spiritual. This means that all of us as God’s children reflect spiritual qualities – such as purity, peacefulness, harmony, and right desire.

We can glimpse through prayer something of everyone’s true nature in the figurative “face of God.” This lifts our perspective above the material picture, helping us see that a relationship that’s difficult or even seems irreparable isn’t doomed. It opens the door to a change of heart and forgiveness, carrying forward the promise and possibilities that stem from our unity with God as God’s own likeness, and with each other as God’s spiritual offspring. Christ Jesus proved this powerful unity through transformed and healed lives.

I had an experience years ago that was a small window through which I could see that our indestructible oneness with God is ever available to turn to for guidance in uplifting relationships.

At the time I started college, I had been studying Christian Science for about a year. I was eager to apply, in my new college experience, the spiritual laws of goodness that I’d been learning meet every need. So when my roommates – who were both sophomores, while I was a freshman – treated me quite coldly at first, my response was to prayerfully consider the God-derived and God-empowered qualities that make up the spiritual identity of everyone. I mentally affirmed that divine Spirit expresses itself in us, its beautiful creation. That’s our true nature.

This enabled me to be kind, understanding, and compassionate with my roommates, even in the face of their coldness. And soon they began to act in the same way toward me. The coldness, which had no place in infinite Love, melted away. Later my roommates told me that their original plan had been to get rid of me as their roommate as soon as possible. Instead, we enjoyed the whole year rooming together and built a relationship that included sharing some of the deeper thoughts of our hearts.

Whatever the human circumstances, we can hold our relationships within a higher, spiritual view. Letting a God-inspired view of others guide our interactions, we can expect with quiet joy to see improvement or changes wherever needed for the benefit of everyone.

Viewfinder

Dancing in the street

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with the Monitor today. Please come back tomorrow when we look at a profile in leadership. For members of the group Heirs of Slavery, the first step toward confronting ancestors’ uncomfortable legacy is humility.