- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Trump indictment: A view from abroad

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

As many of you know, I have arrived in Berlin and will be living in Germany for the next year. (See last Thursday’s Daily for details.) In a Monitor meeting this morning came the obvious question: What do people in Germany think about the indictment of former U.S. President Donald Trump?

There is an easy answer and a somewhat more complicated one. The easy answer is they are fairly appalled. Here are a few choice words from a commentary in today’s Frankfurter Allgemeine, arguably the country’s leading daily newspaper:

“Anyone who hasn’t become jaded three years after the storming of the Capitol and hasn’t written off America as a beacon of democracy will have their blood run cold when reading this document-packed description of Trump’s election fraud attempts. Watergate and every other scandal pale in comparison.”

That’s strong meat. But here’s the thing. It is always easier to be categorical about someone else’s country. I’ve noticed this from Germany to Afghanistan. Problems that seem simple in other countries often feel much more complicated at home. The certainty of black and white fades into shades of gray.

This can be good and bad. Any attempt to overthrow a legitimate democratic election should be addressed with clarity and conviction. Mild rebukes are often the same as tacit acceptance. Yet it’s important to remember this is a legal case, and it is by no means certain what the outcome will be. “The defendant must be presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt in a court of law,” said special counsel Jack Smith.

Moreover, strong stands can sometimes descend into dehumanizing: What are “those people” thinking? Do Germans want to understand why many Americans continue to support Mr. Trump? I hope so. I’ll be encouraging them to follow the story closely and get a better grasp of the complex forces at work. Moral clarity and human decency are both needed for societies to move from strife toward healing.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Questions of honesty at heart of Jan. 6 Trump case

In the most serious indictment yet against former President Donald Trump, jurors will have to decide whether he believed the election was stolen, or whether he intentionally lied about it.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

-

Henry Gass Staff writer

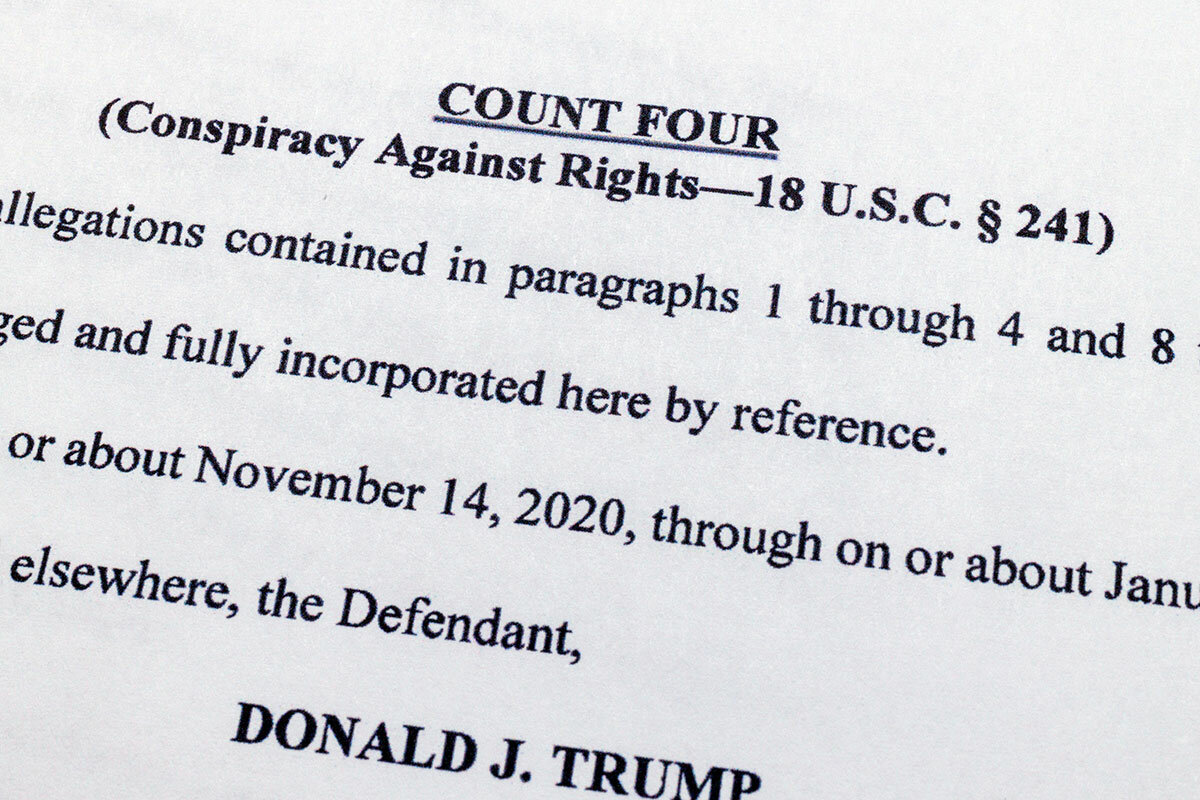

Special counsel Jack Smith’s indictment of former President Donald Trump on charges that he attempted to subvert the 2020 election is a sweeping document that touches on the bedrock functions of American democracy. The indictment alleges the former president engaged in conspiracies to defraud the United States of lawful government, to corruptly obstruct the Jan. 6, 2021, Electoral College count in Congress, and to conspire against the people’s right to vote.

But one of the main themes twining through the document’s 45 pages is honesty – or rather, its alleged lack. Mr. Trump, the indictment states, spread lies that the election had been flipped by fraud and that he was the true victor, despite being told by aides and officials that his claims were untrue.

Mr. Trump’s defense against these charges will likely rely in part on the insistence that he believed what he was saying, notwithstanding others’ objections, and that his actions were not corrupt. The case could thus hinge on a jury’s conclusions about the state of mind of a man whose career has often involved bombast and, at the least, a fondness for exaggeration.

“A key factor here is going to be the defendant’s knowledge and intent,” says Shane Stansbury, a senior fellow at the Duke University School of Law.

Questions of honesty at heart of Jan. 6 Trump case

On New Year’s Day 2021, then-President Donald Trump called Vice President Mike Pence and berated him.

For days Mr. Trump had been pressuring Mr. Pence to use his ceremonial role at the upcoming congressional count of Electoral College votes to help overturn the 2020 election. But Mr. Pence was resisting, saying such a move was unconstitutional. Now he would not even support a lawsuit arguing that the vice president could reject or return a state’s votes.

“You’re too honest,” Mr. Trump said, according to the federal Jan. 6 indictment unveiled on Tuesday.

Special counsel Jack Smith’s indictment of Mr. Trump on charges that he attempted to subvert the 2020 election is a sweeping document that touches on the bedrock functions of American democracy. The indictment alleges the former president engaged in three conspiracies with a crew of aides and advisers: one to defraud the United States of lawful government, another to corruptly obstruct the Jan. 6 Electoral College proceedings, and a third to conspire against the people’s right to vote.

But one of its main themes, twining through the document’s 45 pages, is honesty – or rather, its alleged lack. Four sentences in, special counsel Smith charges that for months after the election, Mr. Trump spread lies that the result had been flipped by fraud and that he was the true victor.

“These claims were false, and the defendant knew they were false,” states the indictment.

What follows is page after page in which prosecutors document specific instances in which Mr. Trump was warned by an aide or top official that particular fraud claims were untrue, and had been proved so, yet he persisted in publicly repeating them.

Mr. Trump’s defense against these federal charges will likely rely at least in part on the insistence that he continued to believe these claims, notwithstanding others’ objections, and that his actions were thus not corrupt at heart.

The outcome of crucial parts of the case could thus depend on a jury’s belief about Mr. Trump’s state of mind – a difficult judgment when it comes to a man whose career has often involved bombast, stubbornness, and, at the least, a fondness for exaggeration.

“Jack Smith knows a key factor here is going to be the defendant’s knowledge and intent, so he placed a lot of emphasis on the defendant’s knowledge and intent. There were whole sections devoted to that,” says Shane Stansbury, a distinguished fellow at the Duke University School of Law and a former assistant U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York.

Why this case is unprecedented

Whatever the outcome of Tuesday’s indictment, its filing is likely to stand as a momentous event in the history of the American government.

It’s not the first criminal indictment against a former occupant of the Oval Office. Mr. Trump faces charges brought earlier this year in the New York borough of Manhattan related to hush money payments to a porn star. Nor is it the first federal criminal indictment against an ex-president. In June Mr. Trump was charged with mishandling of classified documents and obstruction, stemming from his retention of presidential records at his Mar-a-Lago estate following his exit from office.

But it is the first time an ex-president has been charged with alleged offenses that amount to an attempt to use their incumbency to illegally retain office. Previous presidents had all followed the example of President George Washington and participated in peaceful transfers of power.

“The charges alleged in the new indictment go to the heart of our democracy and are more serious than the indictments previously lodged against Mr. Trump in Manhattan or Florida,” says Chuck Rosenberg, a former U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, in an email.

The new case also presents more challenges than the Manhattan or Florida ones, Mr. Rosenberg adds, in part due to the fact that prosecutors will have to prove Mr. Trump acted intentionally.

Mr. Trump’s initial appearance in the case is scheduled for Thursday afternoon before a magistrate judge in federal District Court in Washington. In a statement, the former president slammed the case as “election interference.”

“Why did they wait two and a half years to bring these fake charges, right in the middle of President Trump’s winning campaign for 2024?” Mr. Trump said.

Inside an alleged weekslong conspiracy

The indictment focuses on two months, the period between the November 2020 election and the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. It describes in narrative fashion how Mr. Trump and six co-conspirators attempted a wide-ranging effort to keep him in office.

Besides putting pressure on Mr. Pence, Mr. Trump called various state officials to try to get them to improperly override their state vote totals, according to the indictment. He hosted a chaotic White House meeting where some attendees suggested seizing voting machines from around the country. He attempted to appoint a new attorney general to enlist the Justice Department in his efforts and then backed down when other Justice officials threatened to resign.

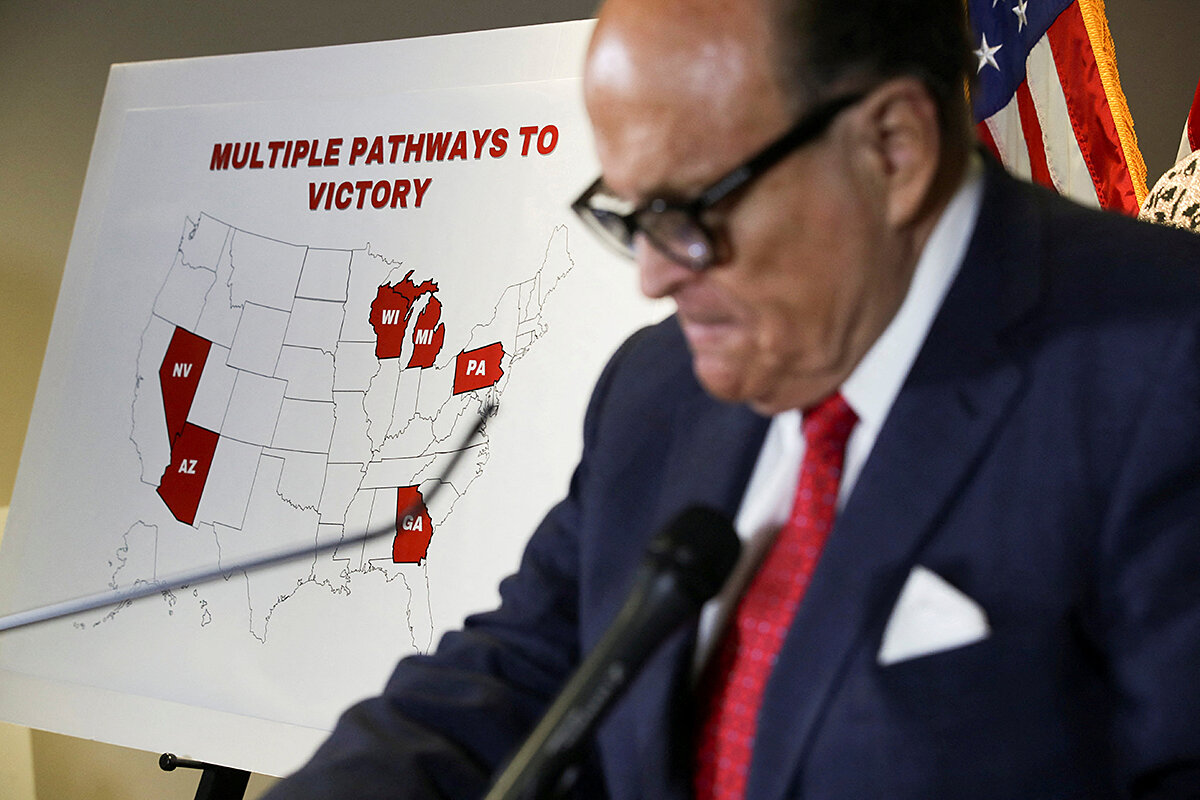

The indictment alleges that some attorneys associated with Mr. Trump helped organize slates of false Electoral College electors from key states, to give an impression of controversy over results where no evidence of election-changing fraud existed.

Mr. Trump insisted at the time, and still insists, that the election was stolen from him by widespread fraud. There is no credible evidence that fraud on that scale occurred in any state.

The Trump team filed numerous election lawsuits prior to Jan. 6 and lost virtually all of them. The indictment alleges that its efforts went far beyond that.

“Yes, if you are losing an election you can look into the legal options on what could or shouldn’t be done. But that’s ‘legal’ options. Jack Smith’s focus is on illegal stuff,” says Michael Gerhardt, a constitutional law professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“Knowingly” – a key word to be weighed in court

Mr. Smith’s indictment also charges that Mr. Trump knew that the public statements he was making about electoral fraud to justify his actions were false. Vice President Pence, Attorney General William Barr and other top Justice officials, the director of national intelligence, officials at the Department of Homeland Security, and senior White House attorneys all told him so.

“In fact, the Defendant was notified repeatedly that his claims were untrue – often by the people on whom he relied for candid advice on important matters, and who were best positioned to know the facts – and he deliberately disregarded the truth,” states the indictment.

Immediately prior to the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol, for instance, Mr. Trump made a number of “knowingly false claims,” in the indictment’s phrase, about election fraud.

He insinuated that 10,000 dead voters had voted in Georgia, for instance. Four days prior, Georgia’s secretary of state had told Mr. Trump this charge was false.

He asserted that there had been 205,000 more votes than voters in Pennsylvania. The acting attorney general and deputy attorney general had explained to him this was false.

Mr. Trump asserted there had been a suspicious vote dump in Detroit. His attorney general had explained to him this was false, and Mr. Trump’s chief allies in the Michigan Legislature, the House speaker and Senate majority leader, had publicly stated there was no evidence of substantial fraud in the state, according to the indictment.

Furthermore, Mr. Trump appeared to accept he had lost the election prior to Jan. 6, at least to some people. In a Jan. 3 meeting with top national security officials, the then-president agreed with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley that no action needed to be taken on a particular matter, due to the impending change in administrations.

“Yeah, you’re right, it’s too late for us. We’re going to give that to the next guy,” Mr. Trump calmly agreed, according to the indictment.

However, this is the prosecution’s story of the case, of course. Mr. Trump’s lawyers may be able to frame these instances differently, pointing to others who had insisted to Mr. Trump that the cited instances of fraud really existed – and that the former president, eager to stay in office, grabbed at their views.

As to his agreement with General Milley, Mr. Trump might have had a fleeting moment of doubt, or just wanted to kick a decision down the road, according to National Review writer Jim Geraghty.

“A lot of this case depends upon the jury reaching a clear conclusion about what Trump was thinking and what he believed at particular times,” Mr. Geraghty writes.

Coming next: an expected indictment in Georgia

Thus the Jan. 6 case may be far from a slam-dunk prosecution.

But it is also likely that Mr. Trump has more indictments to come. In Georgia, Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis appears ready to file an election interference case against the former president for his actions pressuring election officials in her state. State charges could come in the next two weeks.

In January 2021, Mr. Trump famously called Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a fellow Republican, and begged him to “find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have, because we won this state.”

Tuesday’s federal indictment references this and other actions by Mr. Trump and his allies in the state. That does not preclude a Fulton County indictment, however, says University of Georgia law professor John Meixner, a former assistant U.S. attorney in Michigan.

“There won’t be traditional double-jeopardy concerns about dual charges, because the federal charges will in some ways be of a different nature than exactly what would be charged in Georgia, and the federal and state are also separate sovereigns where each can do what they choose,” says Mr. Meixner.

Trump indictment puts US in uncharted terrain

At a time of intense polarization, many Democrats are likely to view Donald Trump’s indictment for an attack on U.S. democracy as long overdue. Many Republicans will see it as further evidence of a “weaponized” legal system.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

The most sweeping and arguably significant indictment of all has now arrived at former President Donald Trump’s doorstep: federal criminal charges over his alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election results. Widely known as the “Jan. 6 case,” it encompasses much more than what happened on that infamous day in 2021, when more than 2,000 Trump supporters stormed the United States Capitol.

Mr. Trump is facing four counts of conspiracy and obstruction surrounding actions he allegedly took to try to prevent the transfer of power. These include pushing officials to “find votes” in key battleground states and arranging fraudulent slates of electors for presentation to Congress as it formally tallied the election results. The indictment cites the former president’s “pervasive and destabilizing lies” as “integral” to his efforts.

In a post on Truth Social, Mr. Trump lashed out at special counsel Jack Smith, accusing him of interfering with the 2024 election by “putting out yet another Fake indictment.”

Compounding this extraordinary moment in U.S. politics, Mr. Trump is running to regain his old office – and is currently the frontrunner for the Republican nomination. He has made his three criminal indictments a central feature of his campaign, arguing that he is the target of a political “witch hunt.”

“There’s no precedent for anything like this” in American history, says George Edwards, a presidential scholar emeritus at Texas A&M University.

Trump indictment puts US in uncharted terrain

Among former President Donald Trump’s many legal woes, the most sweeping and arguably significant indictment of all has now arrived at his doorstep: federal criminal charges over his alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election results and hold on to power.

This is the indictment that Trump opponents have most anticipated. Widely known as the “Jan. 6 case,” it encompasses much more than what happened on that infamous day in 2021, when more than 2,000 Trump supporters stormed the United States Capitol.

Mr. Trump is facing four counts of conspiracy and obstruction surrounding actions he allegedly took to try to prevent the transfer of power. These include pushing officials to “find votes” that would flip the outcome of key battleground states and arranging fraudulent slates of electors for presentation to Congress as it formally tallied the election results. The indictment cites the former president’s “pervasive and destabilizing lies about election fraud” as “integral” to his efforts to obstruct the certification of the vote.

In a post on Truth Social soon after he learned of the new charges, Mr. Trump lashed out at special counsel Jack Smith, calling him “deranged” and accusing him of interfering with the 2024 election by “putting out yet another Fake indictment.”

The case marks the third time the former president has been indicted this year. He was indicted in June in Florida over his retention of classified documents – with major new charges added just last Thursday – as well as in April in Manhattan over alleged hush money payments to a pornography actor. Many legal experts expect he will soon be indicted in a Georgia case over his effort to reverse the 2020 election result in that state.

Even as all this has unfolded, Mr. Trump is running to regain his old office – and is currently the frontrunner for the Republican nomination in the 2024 presidential race. Indeed, he has made his legal troubles a central feature of his campaign, arguing that he is the target of a political “witch hunt.”

As the indictments have piled up, the former president’s position in the polls among likely GOP voters has correspondingly risen, and his dominant position shows little sign of being reversed in the wake of the Jan. 6 charges. Many Republican officials have already come to his defense, lambasting Tuesday’s indictment as politically motivated.

“There’s no precedent for anything like this” in American history, says George Edwards, a presidential scholar emeritus at Texas A&M University.

This extraordinary moment in U.S. politics comes at a time of intense polarization that has shaped voter reactions in dramatically different ways. Many Democrats are likely to view this indictment as long-overdue justice for an attack on American democracy. Many Republicans will see it as further evidence that the legal system has been “weaponized” for partisan purposes.

The latest Monmouth University poll shows that most GOP-aligned and GOP-leaning voters view Mr. Trump as the strongest candidate to beat President Joe Biden in 2024 – with 45% saying he’d “definitely” be strongest and another 24% saying he’d “probably” be strongest. A New York Times/Siena poll released this week found Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden exactly tied among registered voters, with 43% support for each, although other polls have found Mr. Trump would be a weaker general election candidate than some of his Republican rivals.

“Trump has successfully pushed a politics of grievance, where the system is out to get you,” said Patrick Murray, director of the Monmouth poll, in a statement. “In that light, the criminal charges seem to make him an even stronger advocate in the eyes of many Republicans.”

Lawmakers largely fell along party lines in their reactions. In a post on the platform X, formerly known as Twitter, Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy accused the Justice Department of trying to distract from the legal problems of the president’s son, Hunter Biden.

The Democratic leaders in both houses of Congress, Sen. Chuck Schumer and Rep. Hakeem Jeffries, asserted in a joint statement that “no one is above the law” and ended with a plea for calm: “We encourage Mr. Trump’s supporters and critics alike to let this case proceed peacefully in court.”

At least one GOP rival argues Mr. Trump’s mounting legal problems could hurt him politically in the long run. The latest indictment spells “short-term gain, long-term pain,” former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said on CNN last week.

Republican voters may initially flock to the president’s defense, Mr. Christie said – “when there’s a crisis, you rally around your team.” But over time, as details about Mr. Trump’s alleged actions come under increasing scrutiny, “the conduct [behind the charges] is the problem.” That’s likely to be true, he argues, even in the primary.

Mr. Trump has used his previous indictments to rally his base with populist cries of “I am your retribution” and “I’m being indicted for you.” The latest indictment seems likely to turbocharge that message, as it centers on efforts to overturn the 2020 election result. Polls show that more than 60% of Republicans still believe the election was stolen.

At the same time, those arguments seem far less likely to work with politically unaffiliated voters – the fastest-growing portion of the electorate.

“These indictments aren’t endearing independents to Trump,” says Shana Gadarian, a political scientist at Syracuse University, noting that in the last election, independents were key to Mr. Biden’s victory in pivotal battleground states. This latest indictment “is not the death knell for Trump as the [Republican] nominee,” she says, “but I don’t think all these indictments help him in the general [election] at all.”

As a practical matter, Mr. Trump’s legal problems are already a significant financial drain, with campaign finance disclosures this week revealing that his political committees have spent tens of millions of dollars on legal fees. The various court appearances could also keep him off the campaign trail, as he works with his teams of lawyers on his defenses.

It’s also possible some of the cases wind up getting delayed, potentially even until after the November 2024 general election. The federal judge in the documents case has, for now, set a trial date of May 20, 2024 – by which time Mr. Trump could well be the GOP’s presumptive nominee.

The documents case is seen by many legal analysts as the most straightforward among what are ultimately anticipated to be four criminal indictments of Mr. Trump. Many legal scholars see the Jan. 6 case as far more complicated, and potentially more difficult to prove.

Mr. Trump’s lawyers are likely to argue that “he honestly thought that the election had been mishandled and he wanted to correct it,” says Gabriel Chin, a law professor at the University of California, Davis. That means jurors will have to weigh Mr. Trump’s state of mind. “There are lots of situations where, depending on the mental state and the facts, somebody is either doing their job – or committing a crime.”

Likewise, former federal prosecutor Eric Fish says the defense on the conspiracy charge is likely to argue that Mr. Trump and his allies “didn’t intend to prevent votes from being counted, but to prevent the fraud that they believed to be happening.”

Staff writer Patrik Jonsson contributed to this report.

India’s opposition parties team up to beat Modi

A common enemy can be a powerful unifier. But in India, a new rainbow coalition will need to dig deeper if it wants to sweep the polls and stop the country’s democratic backslide.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Omkar Poojari Contributor

Last month, 26 political parties gathered in Bengaluru, India, to announce the formation of the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA). Their goal? To unite India’s fractured opposition ahead of the 2024 election, and to unseat Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been criticized for targeting minorities, curbing free speech, and abusing India’s democratic institutions.

In short, to save India’s democracy.

India has come to exemplify a global trend of democratic backsliding, with the V-Dem Institute in Sweden demoting the country’s status from a “democracy” to an “electoral autocracy” under the BJP’s rule.

“It is imperative that parties committed to the values enshrined in the Constitution of India come together to defeat the BJP,” says senior Congress party spokesperson Rajeev Gowda.

Still, critics say the alliance faces an uphill battle mobilizing voters from different backgrounds. To succeed, INDIA will need to project itself as more than an “anti-Modi” alliance, as well as confront the limitations to its abstract “saving democracy” pitch. Mr. Gowda says that INDIA constituents are working toward a common agenda aimed at bread-and-butter issues like widening the social security net.

Christophe Jaffrelot, a scholar of South Asia politics, says the long-awaited cooperation is inspiring hope for India’s democracy “simply because it offers an alternative to the ruling party.”

India’s opposition parties team up to beat Modi

During India’s tryst with authoritarianism in the 1970s, hope for a democratic revival came from an unlikely place – a prison in the southern city of Bengaluru.

India had taken a dictatorial turn after then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi imposed a state of national emergency. The press was censored, the judiciary compromised, and opposition leaders were thrown in jail. During their stay in the Bengaluru prison, prominent figures from India’s various opposition parties set aside their differences to lay the groundwork for the Janata Alliance, a rainbow coalition of disparate parties ranging from communists to far-right nationalists, which eventually defeated Mrs. Gandhi’s Congress party.

More than four decades later, amid growing concern over India’s democratic backslide, Bengaluru is witnessing a similar bid for cooperation.

Last month, 26 opposition parties gathered in the Karnataka capital to declare a new coalition: the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA). The goal is to unite India’s fractured opposition ahead of the 2024 parliamentary election, and to unseat Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has been criticized for targeting minorities, curbing free speech, and abusing India’s democratic institutions. Critics say the alliance faces an uphill battle – the main challenge being crafting a platform that will mobilize voters from different backgrounds – but history suggests INDIA shouldn’t be written off.

The formation of INDIA brings hope for India’s democracy “simply because it offers an alternative to the ruling party,” says Christophe Jaffrelot, a scholar of South Asia politics who has authored books on the Indira Gandhi and Modi regimes. “... INDIA, like the Janata, does not have a clear prime minister in waiting. ... [But] people may still vote for its candidates to get rid of the ruling party and its anti-democratic and anti-social policies.”

Saving India’s democracy

Not long ago, India was considered a poster child of democracy, but today it has come to exemplify a global trend of democratic recession.

Several independent organizations have sounded alarms over the decline of Indian democracy. While the V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) Institute in Sweden demoted India’s status from a “democracy” to an “electoral autocracy,” the country went from “free” to “partly free” in Freedom House’s study of political rights and civil liberties. Rajeev Gowda, senior spokesperson of the Congress party, the largest opposition party and the leader of INDIA, says that India has seen relentless attacks on “the country’s democratic and federal edifice.”

“Given that BJP rule has worsened religious polarisation and increased divisiveness, violence, and economic inequality, it is imperative that parties committed to the values enshrined in the Constitution of India come together to defeat the BJP,” he says via WhatsApp. “That is the logic for the birth of the INDIA coalition.”

And when it comes to winning seats in parliament, cooperation is essential.

India’s “first past the post” voting system works on a winner-take-all basis. People vote for a single candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins. This, combined with the fact that India has always had a dominant national party and a splintered opposition, means that the incumbent historically has the advantage. The BJP, which replaced the center-left Congress as India’s dominant party in 2014, can win a higher share of seats with a relatively lower vote share. In the 2019 polls, they won 55% of the parliamentary seats with 37% of the popular vote.

By joining forces, INDIA members aim to mitigate that imbalance, though it took years to form an alliance. Dr. Jaffrelot blames the delay on the BJP’s “carrot and stick” approach of keeping smaller, regional parties in check. While Mrs. Gandhi chose to imprison the entire opposition back in the 1970s, many say that Mr. Modi has used central law enforcement agencies to intimidate his opposition.

Parties fell in line out of fear or favor, says Dr. Jaffrelot, and for the same reasons, a few key parties have still opted out of INDIA.

INDIA’s pitch

Sanyam Kumar, a banking professional who voted for the BJP in the previous elections but now finds himself on the fence, agrees that the Modi administration has undermined India’s democracy. But he says he’ll still vote for the BJP if INDIA can’t produce a concrete, compelling platform.

“I do not think they can get me to vote for them if their only [unique selling point] is ‘saving democracy.’ I am not buying that,” he says, opining that no matter who is in power, the government always encroaches on liberties. “They need to talk about the real issues to get my vote.”

Yashraj Wade, a Mumbai-based consultant who leans toward the BJP, is also skeptical. He sees INDIA as a hodgepodge of parties threatened by the mass appeal of Mr. Modi.

“Their single-point agenda is to be anti-Modi,” he says, adding that sticking to this narrow focus “would only weaken them further and strengthen the BJP.”

Indian political scientist Suhas Palshikar agrees that most governments succumb to democratic transgressions – “All jailers seek to keep the prison intact,” he says, referring to draconian laws implemented under previous ruling parties – but is quick to point out that the BJP has been threatening the very foundations of India’s democracy. Mr. Palshikar also contests the idea that INDIA is little more than a Modi hate club.

“The anti-Modi tag has been employed by the BJP and Modi himself and the pliable media has dutifully picked it up,” he says. “The initial brief statement by INDIA does go beyond Modi,” touching on the Manipur conflict, economic crisis, unemployment, and inflation.

Still, to succeed, INDIA will need to project itself as more than an “anti-Modi” alliance, as well as confront the limitations to its “saving democracy” pitch. Indeed, in a country with rampant poverty, inequality, and hunger, the average voter’s choices are driven more by bread-and-butter issues than abstract issues of democracy. Mr. Gowda, from the Congress party, says that INDIA constituents are working toward a common agenda aimed at providing relief to the poor and widening the social security net.

Driving this cooperation is the same force that brought the member parties to Bengaluru in the first place.

“They have realised – at last – that their very existence was at stake,” says Dr. Jaffrelot, in an email. “If opposition parties do not close ranks, their fate is sealed.”

Why Brazil’s ‘fake news’ law keeps stalling

Brazil wants to crack down on fake news by reining in powerful, large social media platforms. But who determines “the truth” – and how?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Who, if anyone, is responsible for safeguarding the truth?

That question is at the heart of fierce debate in Brazil as the Chamber of Deputies starts a new term this month and is expected to vote on the Law on Freedom, Responsibility, and Transparency on the Internet.

The legislation was first put on the table in 2020 to curb misinformation following the election of Jair Bolsonaro, but the situation was exacerbated by disinformation spread during the pandemic. It gained new steam following Jan. 8 riots in Brasília, which were spurred by false claims that last year’s presidential election was rigged. Growing attacks in schools, linked to online hate speech, have added urgency to the issue.

Proponents see it as an opportunity to rein in the power of large social media companies in Brazil, holding them accountable for the unfettered spread of content from which they profit. Critics view it as a threat to freedom of expression that puts too much of the onus on corporations. Others say the responsibility needs to be shared.

“It is not up to the companies alone, nor to the state alone,” says Rafael Zanatta, executive director of the nonprofit Data Privacy Brasil Research Association. “This also involves communities and citizens.”

Why Brazil’s ‘fake news’ law keeps stalling

To some, it’s the “fake news” law; for others, a censorship bill. In Brazil, the Law on Freedom, Responsibility, and Transparency on the Internet has been the subject of fierce debate: Who, if anyone, is responsible for safeguarding the truth online?

The legislation was first put on the table in 2020 to curb misinformation following an election cycle dominated by unvetted information shared on social media and won by Jair Bolsonaro. “Fake news” – pronounced in English – quickly became a household term and a growing concern across Brazil. The COVID-19 pandemic raised the stakes of misinformation.

The law was quickly approved in the Senate but has yet to be voted on in the Chamber of Deputies, where it has faced intense pushback. Supporters are hopeful a vote will be rescheduled this term, which began this month.

Proponents see the legislation as an opportunity to rein in the power of large social media platforms in Brazil, holding them accountable for the unfettered spread of content from which they profit. Critics view it as a threat to freedom of expression that puts too much of the onus on corporations. Some say the responsibility needs to be shared.

“It is not up to the companies alone, nor to the state alone,” says Rafael Zanatta, executive director of the nonprofit organization Data Privacy Brasil Research Association. “This also involves communities and citizens. ... There is no single leviathan that can protect us all.”

“Real freedom”?

The legislation gained new steam following Jan. 8 riots in Brasília, which have been blamed on widely disseminated claims that last year’s presidential election was rigged. Growing attacks in schools, linked to online hate speech, have added urgency to the issue.

“The scene today is worrying. Things can’t continue the way they are,” says Davi Brito, a law student in Rio de Janeiro who plans to become a pastor. He understands concerns about freedom of expression, in particular when it comes to religious freedom, but holds that “extreme freedom, without any limitations, isn’t real freedom.”

At the same time, he wonders about government overreach. In Brazil, WhatsApp is the primary channel of communication, and three-quarters of the population uses one of the other large social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (now known as X).

“Every government tries to benefit itself somehow,” Mr. Brito says. “I’m scared the law could be used in that way.”

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva has confronted false information head-on since taking office, launching a working group focused on hate speech and misinformation as well as a website dedicated to debunking fake news about the federal government and its projects.

If approved, PL 2630, as the law is formally known, would hold large social media companies, including messaging apps like WhatsApp, legally responsible for monetized content containing “untrue facts” as well as content that could incite crimes, such as terrorism, racism, and violence against minors and women. Under the current Internet Civil Framework, social media platforms are not responsible for content shared on their sites and are only required to remove content if ordered by a court.

“Underlying factors”

When the bill was first passed in the Senate, the United Nations Human Rights Council sent a letter to the government of Brazil noting it was “seriously concerned” about potential violations to freedom of expression.

In a 2021 UNHCR report on disinformation, the current special rapporteur on freedom of speech contends that any restrictions to freedom of speech “must be exceptional and narrowly construed.” The report urges governments to consider underlying factors of widespread misinformation, noting that disinformation is “not the cause but the consequence of societal crises and the breakdown of public trust in institutions.”

That stance helps explain why many regular Brazilians are on the fence.

“Lots of lives were lost due to fake news,” says Hércules Faria, a history student at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, referring to misinformation spread during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet it’s not always easy to define fake news. Though he doesn’t believe Brazil is heading toward anything resembling the authoritarian dictatorship that prevailed until 1984, he has reservations about the potential implementation of the law.

“I’ve heard lots of people say that it would be a type of censorship, but I don’t know to what extent that’s true,” he says. “I would find it very necessary that there be transparency of the body that’s going to be implementing this. That’s a must.”

Others are more willing to trust those moderating content.

“I don’t see it as censorship. It is possible to know if something is a lie or not,” says Denise Faria, a retired high school history teacher and longtime Lula supporter.

Countries around the world are grappling with how to oversee social media platforms. Australia passed the Online Safety Act in 2021 to regulate the removal of harmful content online. The European Union’s Digital Services Act of 2022 aims, in part, to tackle the spread of disinformation. In the United States, most state legislatures have introduced some kind of bill for regulating social media, ranging from banning content censorship to requiring new mechanisms for reporting and removing hate speech.

Meanwhile, fake news laws have been used in Russia and Turkey to crack down on opposition voices.

Who decides “the truth”?

In Brazil, Big Tech companies have campaigned forcefully against the legislation. In the lead-up to a planned vote in the Chamber of Deputies in May, Google users saw a message on the search engine’s homepage saying the law could “increase confusion about what is true or false,” which linked out to an opinion article criticizing the bill. The next day, Google was given two hours to take it down. Messaging app Telegram sent a note to users warning them that the bill is “one of the most dangerous ever considered in Brazil.”

“The platforms spent much more money to campaign against the bill here in Brazil than they did, for example, in Europe, which has a broader regulatory tradition than ours,” says Bia Barbosa, advocacy manager for the Latin America bureau of Reporters Without Borders. Wherever they operate, she says, the platforms position themselves against any mechanism that will “result in the possibility of reducing their profits [or] generate responsibility for the content that circulates.”

Some civil society organizations have been vocal in their support of PL 2630; over a dozen groups signed an open letter highlighting the need for transparency and accountability on the part of social media companies. These companies generally follow their own content moderation policies. Advocates for the bill worry about the false and hateful posts that make it through the cracks.

“Self-regulation is not enough to ensure that the internet is a healthy environment,” says Ms. Barbosa.

Others argue that misinformation is better fought by improving civic education and media literacy, empowering regular citizens to discern fact from fiction. And even advocates see issues with the bill as it stands. For example, it lacks a provision for an autonomous and independent authority that would enforce and regulate the legislation.

For Mr. Brito, that’s the sticking point: “Who’s going to have the right to determine what is truth?”

Graphic

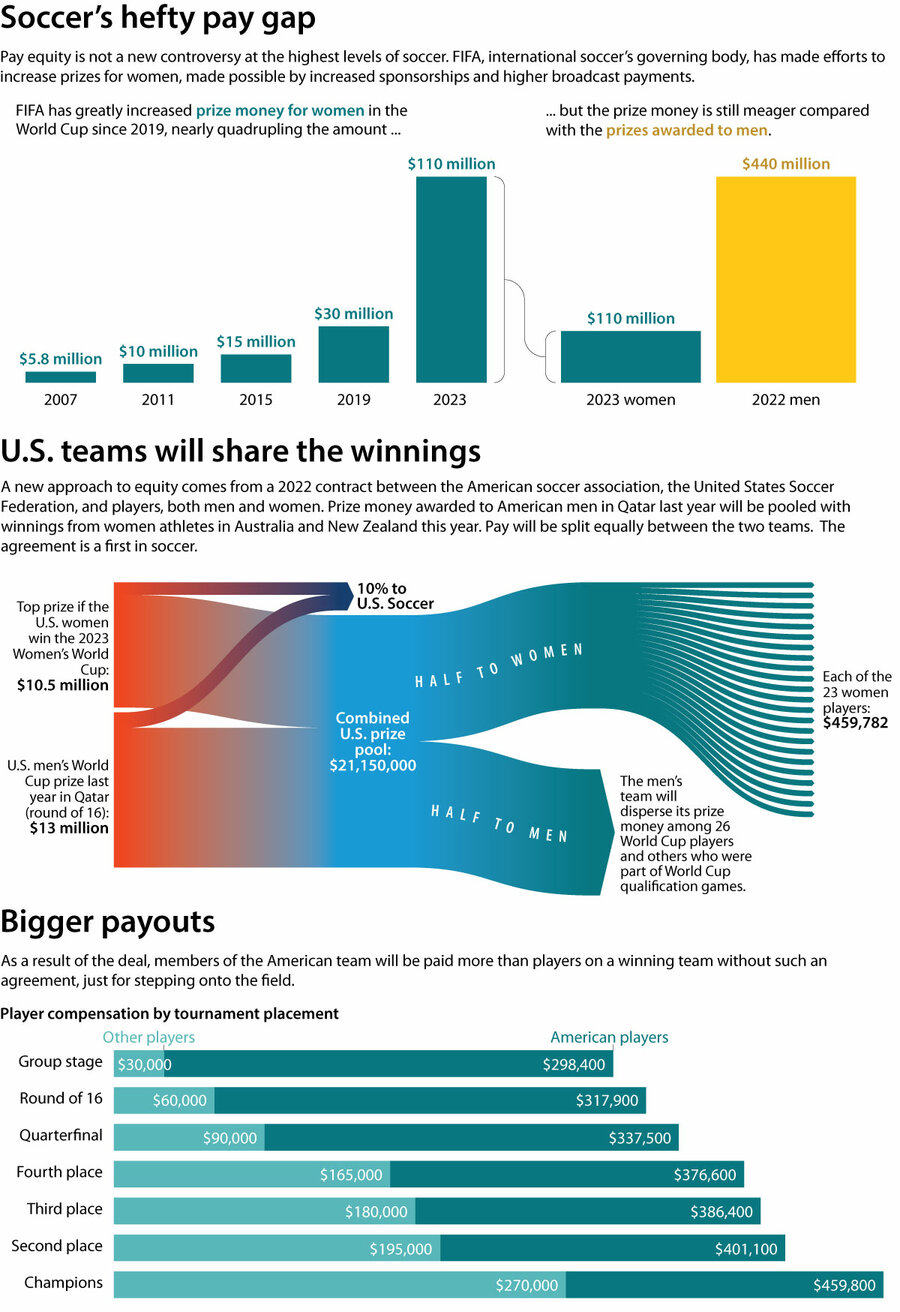

At Women’s World Cup, a focus on pay fairness

The FIFA Women’s World Cup is setting records for viewership and ticket sales. Yet as our charts show, women players lag far behind men in pay, a gap that some nations are trying to address.

The Women’s World Cup 2023 is underway in Australia and New Zealand, and it’s smashing television viewership and ticket sales records. FIFA, the organizer of the World Cup, says fans have already bought nearly 1.7 million tickets to the games, and corporate sponsorship is surging. More eyes are focused on the biggest event in women’s soccer than ever. But fans and observers are again asking why the world’s best women players should be awarded so little compared with those on the men’s teams.

This year’s prize pool totals $110 million, a giant increase from $30 million in 2019 but a far cry from the men’s 2022 World Cup trove of $440 million. Unhappy with this imbalance, American players from both the men’s team and world champion women’s team reached a deal last year with the United States Soccer Federation, the sport’s national governing body, that makes compensation for athletes fairer. Under the new deal, men and women will pool their winnings and split them 50-50.

FIFA pays prize money to each country’s soccer association, not directly to players. Many countries’ associations pay players per the terms of negotiated labor contracts. But about two-thirds of teams do not have such contracts, leaving their soccer associations to disburse prize money as they see fit. Athletes have complained about late and missed payments, and unfair compensation. The average salary for Women’s World Cup players worldwide in 2022 was $14,000. Earlier this year, FIFA promised to ensure each woman in the tournament was paid at least $30,000 but admitted in June that it could not guarantee national associations would distribute the money in that way.

Some national federations, such as those in Australia and Japan, have made their own collective bargaining agreements intended to improve pay for women athletes, and others, such as Denmark’s, offer player bonuses. But the majority of players in this year’s tournament will not benefit from such agreements and are subject to FIFA’s pay structure.

FIFA says it will aim for pay parity for the 2026 and 2027 men’s and women’s World Cups. Until then, deals like this may be the best way to ensure that prizes for the top tournament are distributed equitably.

– Jacob Turcotte, Graphics editor

FIFA, New York Times

Can unauthorized immigrants legally drive? More states say yes.

More U.S. states are allowing driver’s licenses for unauthorized immigrants, while Florida adds restrictions. The debate stirs arguments around road safety and national security.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Scared to drive without a license in her Colorado mountain town, Laura would walk everywhere last year with her two young children in tow. The unauthorized immigrant from Colombia couldn’t risk getting caught behind the wheel.

After earning a license last fall, Laura, whose real name is not being used for privacy reasons, says she feels “useful” now – “like I can do whatever I need.” She drives around Gunnison County daily, including to work as a housekeeper and excursions to the playground.

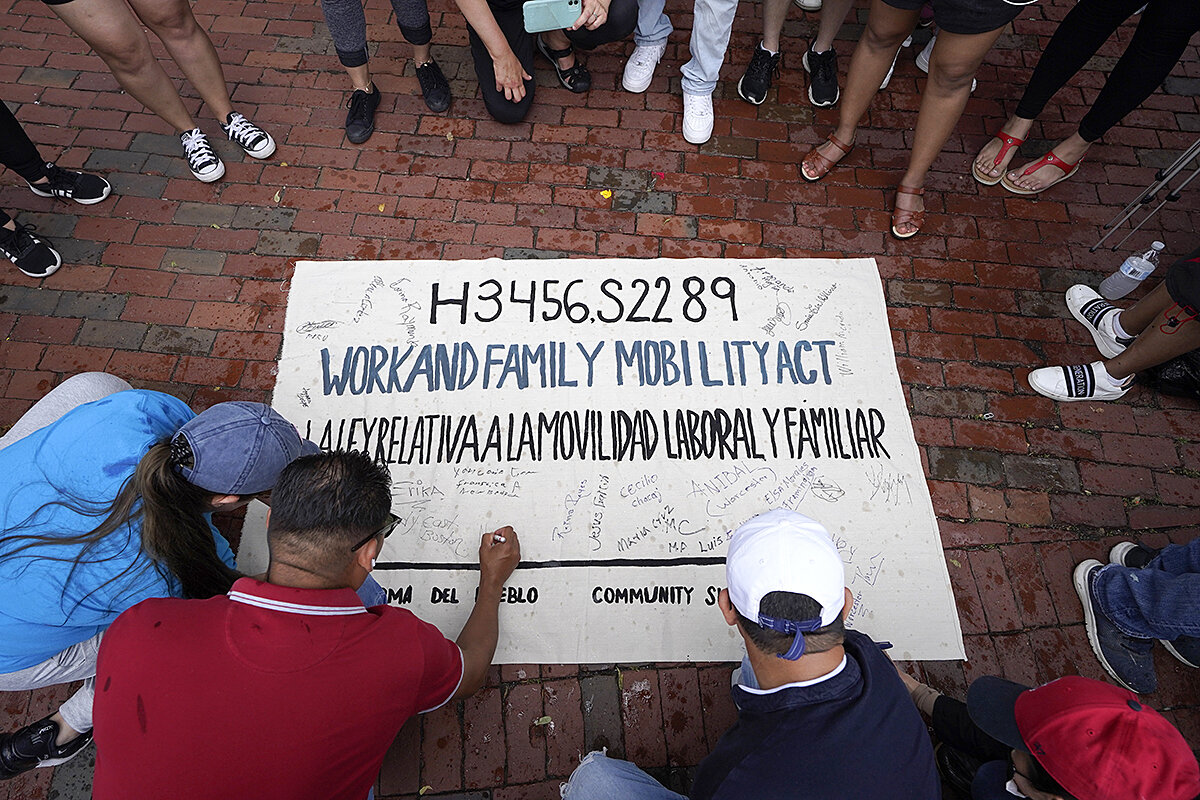

The United States hasn’t authorized Laura to stay, but the state has allowed her to drive. Colorado has extended the right to drive regardless of immigration status for 10 years – and some states have done so for even longer. In all, 19 states and the District of Columbia have laws that allow the issuance of licenses to unauthorized immigrants, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, where new laws went into effect last month. Minnesota’s new law begins on Oct. 1.

Advocates have long made a safety argument – that the absence of a license hasn’t kept unauthorized immigrants off the road, so it’s better to have them certified. At the same time, some other states are home to powerful opposition to the idea of allowing these licenses, arguing they reward illegal immigration and could undermine national security.

Can unauthorized immigrants legally drive? More states say yes.

Scared to drive without a license in her Colorado mountain town, Laura would walk everywhere last year with her two young children in tow. Whether headed to the school, gym, or grocery store, the unauthorized immigrant from Colombia couldn’t risk getting caught behind the wheel.

During one walk in April of last year, exposed to the cold, she saw her first grade son’s small ears turn purple.

“I remember that I was crying at home. ... It was hard at times,” says Laura, whose real name is not being used for privacy reasons. She knew she needed a car.

After earning a license last fall, Laura says she feels “useful” now – “like I can do whatever I need.” She drives around Gunnison County daily, including to work as a housekeeper and excursions to the playground. Laura chauffeurs her son and daughter there on a recent afternoon, the pair chattering away in the back seat.

“Right now, I’m saving the world,” says her 8-year-old son, engrossed in a Spider-Man game.

The United States hasn’t authorized Laura to stay, but the state has allowed her to drive. Colorado has extended the right to drive regardless of immigration status for 10 years – and some states have done so for even longer. In all, 19 states and the District of Columbia have laws that allow the issuance of licenses to unauthorized immigrants, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, where new laws went into effect last month. Minnesota’s new law begins on Oct. 1.

Advocates have long made a safety argument – that the absence of a license hasn’t kept unauthorized immigrants off the road, so it’s better to have them certified. Supporters also say a simple traffic stop without ID could result in deportation and family separation.

At the same time, some other states are home to powerful opposition to the idea of allowing these licenses, arguing they reward illegal immigration and could undermine national security. In Republican-led Florida, a new law refuses recognition for certain out-of-state licenses issued exclusively to unauthorized immigrants.

Meanwhile, license or not, the lives of an estimated 11 million people in the U.S. – roughly 3% of the population – remain precarious with various challenges to legalizing their status without major federal immigration reform. States, however, have long taken widely varying approaches to providing or limiting access to benefits like licenses. In parsing the debate, it can be helpful to distinguish between immigration policy and immigrant policy, says Muzaffar Chishti, senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute.

“Immigration policy decides who do we let in and who do we kick out,” which is the federal government’s role, he says.

On the other hand, immigrant policies have to do with integration, like the issuance of driver’s licenses by states, he adds.

The question then becomes: Once they’re here, “how do you treat them?”

Extending and restricting licenses

Though the enforcement of national immigration law is primarily a federal matter, states can extend or restrict privileges to individuals who can’t prove their lawful presence. Examples include limited health care, college tuition, and driver’s licenses – often with limits on use for identification purposes.

Florida has placed new rules and penalties around the employment of unauthorized immigrants, as well as their transport into the state – the subject of a lawsuit filed by immigrant advocacy groups last month. In effect since July 1, the new law grants the state “the most ambitious anti-illegal immigration laws in the country,” stated Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, who’s also running for president.

The Sunshine State also no longer recognizes certain out-of-state driver’s licenses issued exclusively to these individuals. Florida currently lists licenses from Connecticut and Delaware as newly invalid, after removing Hawaii, Rhode Island, and Vermont in recent weeks due to confusion around those states’ license policies.

The new license law invites two questions, says Rick Su, professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law.

“One is, how much effect will it actually have at the end of the day, as opposed to just being sort of a political move?” he says. “And then the second is, if it does have effect, and is zealously enforced, does this open up a separate legal question?”

For instance, it would become more legally complicated if Florida decided to target out-of-state license types that weren’t exclusively reserved for unauthorized immigrants. At that point, adds Mr. Su, “you are excluding and punishing anyone from that state.”

Drivers “more at ease”

Supporters of letting unauthorized immigrants legally drive stress benefits for community safety and well-being. Aware of several driving-related deportations in the early 2000s, Flora Archuleta joined fellow activists pushing for the permission in Colorado, which was later granted in 2013.

“People were so afraid of driving, even taking their kids to school,” says Ms. Archuleta, executive director of the San Luis Valley Immigrant Resource Center. (The Supreme Court has ruled that states generally can’t deny public school to children of unauthorized immigrants.)

Today, those drivers are “much more at ease,” says Ms. Archuleta. They’re purchasing car insurance, which is required for all Colorado car owners like Laura.

Some research also seems to support the road-safety argument. A California study and reporting in Connecticut suggest a link between these laws and reduced risk of hit-and-run crashes.

Still, there are caveats related to federal intervention. At least seven states have given personal driver information to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in recent years, a 2021 Center for Public Integrity investigation found.

That collaboration isn’t guaranteed, however. In its fiscal year 2022, the Colorado Division of Motor Vehicles received two requests from ICE, which were both denied “in accordance with state law” that concerns personal identifying information, wrote Derek Kuhn, a spokesperson for the Colorado agency, in an email.

In response to a request for comment, an ICE spokesperson wrote that the agency “is able to employ and leverage various databases and forms of technology under its broad statutory authority in the furtherance of criminal investigations, and as appropriate, for interior civil immigration enforcement.” The spokesperson did not address the Colorado requests directly, citing “operational security.”

“Immigrants have to be mindful that there is some database that the state has access to,” says Mr. Chishti of the Migration Policy Institute. And if states share that with the federal government, he says, those drivers become “vulnerable.”

National Conference of State Legislatures

Easier to be in the U.S. illegally?

Traditionally conservative sectors have backed these driving privileges for safety and practicality reasons, including Idaho farmers and Massachusetts police chiefs. Still, many critics argue the laws condone the unauthorized presence of immigrants who may have originally entered the U.S. without vetting.

“If you want to discourage people from violating the law, you don’t provide them with documents that make it easy for them to be in the country illegally,” says Ira Mehlman, media director at the Federation for American Immigration Reform. Additionally, states will often accept foreign documents as part of license applications, which to him raises concerns around identity verification.

Near Providence, Rhode Island, Krysta’s life is far removed from the political fray. Krysta, who asked that her last name not be published, for privacy, has tried to reserve an appointment with the DMV to pursue a driver’s privilege card since the law in the state began July 1, but slots have filled up.

The Guatemalan has driven unlicensed for 16 years to and from work, medical appointments, and school, careful to avoid crashes and never venturing far from home. A license will not only relieve her but also her three children, U.S. citizens who’ve lived in fear of their mother’s potential deportation.

The first thing she’ll do with her card in hand?

“Celebrate,” she says. “Take my kids and husband and get away. Drive far, take a trip.”

Troy Sambajon contributed reporting from Boston.

National Conference of State Legislatures

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A roundabout approach to climate change

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Perhaps one solution to global warming is not to deal with only greenhouse gas emissions. This November, at the next United Nations conference on climate change, a key focus will be on water safety and access – for the first time in the history of such gatherings. And there’s a reason for that. Shared concerns about water security are showing how a global conversation on one natural resource crisis can help build trust and shared responsibility to help solve another.

Water users on the Colorado River, for example, are finding new ways to cooperate and compromise amid a prolonged drought. That opens new opportunities for shared solutions on energy. In Africa, projects to generate safe drinking water have led to the creation of alternatives to the use of firewood and fossil fuels to boil water. Around the world, disrupted weather patterns are compelling scientists, business leaders, and policymakers to share information on water.

Climate change has forced a new focus on other ecological issues, such as water. As a shared and renewable resource, water is amplifying humanity’s ability to defuse crisis through unity. Collaboration on water issues opens a new path for climate solutions.

A roundabout approach to climate change

Perhaps one solution to global warming is not to deal with only greenhouse gas emissions. This November, at the next United Nations conference on climate change, a key focus will be on water safety and access – for the first time in the history of such gatherings. And there’s a reason for that. Shared concerns about water security are showing how a global conversation on one natural resource crisis can help build trust and shared responsibility to help solve another.

Water users on the Colorado River, for example, are finding new ways to cooperate and compromise amid a prolonged drought. That opens new opportunities for shared solutions on energy. In Africa, projects to generate safe drinking water have led to the creation of alternatives to the use of firewood and fossil fuels to boil water. Around the world, disrupted weather patterns are compelling scientists, business leaders, and policymakers to share information on water.

As the Global Commission on the Economics of Water observed in a recent report, “We can convert the water crisis to an immense global opportunity, for economy-wide innovation and a new social contract between all actors – with justice and equity at the centre of our efforts.”

Climate change has forced a new focus on other ecological issues, such as water. The U.N. estimates that 4 billion people globally live without consistent access to safe water sources and that by 2030 some 700 million people will be displaced by water insecurity. As a shared and renewable resource, water is amplifying humanity’s ability to defuse crisis through unity. Collaboration on water issues opens a new path for climate solutions.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Healing trauma – is it possible?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Kate Robertson

No matter how inescapable the aftereffects of a traumatic experience may feel, there is always a path to healing and peace of mind, as this short podcast explores.

Healing trauma – is it possible?

Today we’re sharing an audio podcast on healing trauma. It explores how a growing awareness of God as always present and entirely good can free us from the mental baggage of traumatic experiences. And a woman shares how she experienced this firsthand after years of struggling with the aftereffects of childhood traumas.

To listen, click the play button on the audio player above.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “Healing trauma – is it possible?” – the June 12, 2023, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast on JSH-Online.com.

Viewfinder

Moon shadows

A look ahead

We’re so glad you could join us today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow, when Scott Peterson, just back from the front, looks at the state of the Ukrainian counteroffensive.