- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Donald Trump’s new opponent for the White House

Former U.S. President Donald Trump has a new adversary in his attempt to win back the White House. It’s not special counsel Jack Smith, or Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and other GOP rivals. It’s not even President Joe Biden.

It’s the clock.

Next year, Mr. Trump will face a long, demanding campaign schedule. Primary season begins with Iowa’s Republican caucuses on Jan. 15 and stretches through June. If he wins the nomination – and he’s currently the faraway front-runner – general election rallies and other events will suck up his time.

But he might also face a grueling legal schedule, preparing for and attending criminal trials.

Mr. Trump’s attorneys have made clear that they would prefer his federal criminal cases be postponed until after the election. That’s possible, but not likely.

His classified documents trial in Florida is set to begin in May – though that could change. This week’s indictment on election charges related to Jan. 6 appears designed to produce as speedy a trial as possible. Mr. Trump is the sole defendant. Counts are narrowly focused.

The judge in the trial has set a first hearing on Aug. 28, saying she’ll pick a trial date then.

The bottom line: Next year’s election could be unlike any in American history, with traditional issues swept aside for a swirling focus on courtroom drama and Mr. Trump’s legal fate, including possible jail time.

“This election may very well be about Donald Trump’s personal freedom,” longtime GOP strategist Ari Fleischer told The Associated Press this week.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Is an Israel in crisis weaker? Tensions rise on border.

One measure of a nation’s strength is social cohesion. Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah has been closely watching Israel’s wrenching protests over judicial reform, in which military reservists have played a prominent role.

-

By Neri Zilber Contributor

Delivering an intelligence assessment to Israel’s top military officers last December, the brigadier was, overall, optimistic about the coming year. “Israel is perceived in the region ... as a strong and stable player, with high economic and scientific capabilities,” he said.

His survey of areas of concern ranked Israel’s crisis-wracked northern neighbor, Lebanon, and the threat posed by the Iranian-backed Hezbollah movement, as a distant fourth.

Fast forward eight months. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government has thrown Israel into unprecedented turmoil with its push to overhaul the country’s judicial system, spurring warnings of damage to Israel’s economy and national security.

Israel’s border with Lebanon has become the scene of growing tensions with Hezbollah that many fear could escalate into open conflict. Indeed, Israeli military intelligence recently raised the chances of war with Hezbollah to their highest since 2006, when the foes fought a 34-day campaign.

“Hezbollah sees the internal situation in Israel and views it as weakness,” says one Israeli security official, adding that Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah does not want war but is using the border friction to erode Israeli deterrence and strengthen Hezbollah’s standing in Lebanon.

Israeli officials assess that strategy as risky. “You know how something like this starts, but you don’t know how it ends,” warns the security official.

Is an Israel in crisis weaker? Tensions rise on border.

On a sunny winter day last December, Israel’s most powerful military commanders, both current and former, gathered at a swanky Tel Aviv beachfront hotel to discuss the weightiest security matters facing the Jewish state.

Addressing the conference held by the army’s in-house intelligence think tank, the research division chief, Brig. Gen. Amit Saar, was, overall, optimistic as he laid out the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) outlook for the coming year.

“Israel is perceived in the region … as a strong and stable player, with high economic and scientific capabilities,” Brigadier General Saar said.

His survey included the challenges facing Iran, unrest in the West Bank, and relative stability in Gaza. A distant fourth concern was Israel’s northern neighbor, Lebanon, and the threat posed by the Iranian-backed Hezbollah movement.

“Lebanon is a country in a deep crisis, and this creates deep tension for Hezbollah. Today [Hezbollah] is the sovereign in Lebanon, but it has the best tickets on the Titanic,” he said, alluding to Lebanon’s cratering currency, lack of medicine and electricity, and overall political chaos.

Fast forward eight months.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government, which took power in late December, has thrown Israel into unprecedented turmoil with its push to overhaul the country’s judicial system.

Many of the former senior officials present at the December conference have become highly public dissidents, warning of the damage to national security wrought by the government’s agenda and even supporting the refusal by thousands of military reservists to serve under a budding illiberal regime.

By every metric the Israeli economy has suffered, while scientists, doctors, and tech entrepreneurs either prepare emigration plans or march in the streets alongside hundreds of thousands of their fellow citizens.

Israel is no longer as strong or as stable as it was mere months ago, and its border with Lebanon has become the scene of growing tensions and Hezbollah provocations that many fear could escalate into open conflict.

Indeed, Israeli military intelligence recently updated its assessment, putting the chances of an Israel-Hezbollah war at their highest since 2006, when the two foes fought a 34-day campaign.

“Hezbollah sees the internal situation in Israel and views it as weakness,” says one Israeli security official.

Last week, after parliament passed the first of the governing coalition’s judicial overhaul bills, spurring mass protests, Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah described it as “the worst day in the history of the Zionist entity.”

“Israel has embarked on a path, God willing, of collapse, fragmentation, and doom,” he crowed.

Border provocations

For over a year, but especially in recent months, Hezbollah has become more aggressive, openly establishing border posts and deploying its forces on the frontier, and either actively or tacitly launching a series of exceptional attacks.

In March, a Hezbollah militant managed to cross the border, travel 50 miles deep into the heart of Israel, and lay an advanced explosive device by a highway. The ensuing blast only wounded one passing Israeli motorist; the militant, attempting to flee back into Lebanon, was killed by Israeli commandos as he tried to detonate a suicide vest.

“If the explosion had hit a bus of soldiers on the highway and 10 people were killed, this wouldn’t have ended with nothing,” says Brig. Gen. Assaf Orion, a retired IDF officer now at the Institute for National Security Studies in Tel Aviv, referring to Israel’s muted retaliation to the attack.

In April, amid tensions at Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque compound, Hezbollah allowed local Palestinian groups to fire more than 30 rockets at Israel – the heaviest barrage from Lebanon since 2006. Israeli jets struck agricultural fields in response.

In late May, Hezbollah militants crossed the international boundary into Israeli-held territory near the Golan Heights, and set up two tents, precipitating a stand-off that international mediators are still working to resolve. In a bid to mitigate the crisis, the IDF refrained from making the incursion public for several weeks.

More recently, near-daily provocations have taken place, with Hezbollah operatives attempting to sabotage the border fence and even firing an anti-tank missile at a disputed Israeli village that straddles the frontier.

Nevertheless, says the security official, Israeli intelligence’s official assessment is that Mr. Nasrallah still does not want war but is using the increased friction on the border to erode Israeli deterrence and strengthen Hezbollah’s standing as Lebanon’s “true protector.”

Israeli officials assess the strategy as risky, but surmise that the Hezbollah leader may be gambling that any flare-up can be contained to a few days of fighting, similar to the many clashes between Israel and Gaza-based militants in recent years.

“You know how something like this starts, but you don’t know how it ends,” warns the security official. “But both sides don’t have an interest in a total war.”

Brigadier-General Orion is more pessimistic, saying no matter the intentions of either side, the confrontations increase the chances of miscalculation.

“We’re treading on a very narrow ledge with no guardrails, even if Netanyahu himself is very careful and both sides don’t want it,” he says. “The tactical level [on the ground] will dictate what happens. … It could be a matter of inches.”

Does Hezbollah want war?

There are those in Israel, however, who offer an even more dire assessment, arguing that far from being simple muscle-flexing over a border dispute, Hezbollah’s recent behavior indicates a genuine desire for war – no matter the likely devastating cost to both itself and Lebanon.

“Hezbollah views Israel as the platform through which it can accelerate its … takeover of Lebanon,” says Major Tal Beeri, a former Israeli intelligence officer and research director at the Alma Research and Education Center in northern Israel.

“Hezbollah knows it will take heavy losses, they’re not idiots. But at the end of the war it will be the strongest actor in Lebanon with all of the others weakened. … Just look at how since the 2006 war it has become stronger, increasing its military capabilities and political standing,” Major Beeri adds.

In his view, Mr. Nasrallah has been genuinely surprised at the lack of a sharper Israeli response, including possible war.

The reason for Israel’s restraint (so far), analysts argue, is the knowledge that Hezbollah has amassed a vast arsenal, including precision missiles capable of hitting key Israeli infrastructure and institutions. Israel estimates that in the opening stages of any renewed conflict, Hezbollah will have the ability to fire 4,000 rockets and missiles at Israel daily, compared with the 100 per day it managed in 2006.

Whatever Mr. Nasrallah’s current intent, Israel, for its part, has since 2006 been extensively training and preparing for a conflict with Hezbollah – including the launch of a major air and ground offensive against Lebanon if war breaks out. Security analysts maintain it would be, by some measures, the most destructive Arab-Israeli war since 1973.

Would conflict bring unity?

Amid these growing tensions on the Lebanon border and continued domestic unrest – including inside the military – Israeli officials have pushed back rhetorically against the proposition that Israel has been weakened. They argue that in any future conflict, the country and military would remain united.

“Regarding Nasrallah’s threats from his bunker, we are not impressed,” Mr. Netanyahu said at the weekly cabinet meeting Sunday. “At the crucial moment, he will find us standing together, shoulder to shoulder. Even Nasrallah knows that it is worth neither his while, nor Lebanon’s, to put us to the test.”

A statement released after a meeting the next day between the prime minister and his top security chiefs, purposefully delayed for days until after the parliamentary vote last week, was left deliberately vague as to the government’s intentions.

What damage the reservists’ protest has inflicted on Israeli capabilities is also unclear, as the military tries to publicly downplay the scale of the no-shows and personally convince reservists to resume their service. The impact may only become apparent in the coming weeks as the thousands of combat pilots, intelligence specialists, special forces commandos, and others refuse to report for duty.

“At this point in time, the IDF is operationally ready,” the top military spokesman said last week in an unprecedented statement. “If reservists do not show up for reserve duty in the long term – there will be damage to the military’s readiness.”

In a deeply divided society, if a security crisis were to materialize, it could either help mend what has been broken over the past seven months or simply exacerbate tensions and push Israel over the brink.

“A security escalation is the best way to break apart the protest movement, and [Netanyahu] does have a legitimate reason” to respond to Hezbollah's actions, said one leader of the IDF reservist protest group last month.

“Some [reservists] will report for duty, some won’t. And [the government] will simply continue legislating” its judicial overhaul.

Anti-trans law leaves many Russians asking, ‘Who’s next?’

The Kremlin’s ban on gender-affirming care signals an acceleration of Russia’s authoritarian drift, with treatment of trans people as a signal to distinguish Russia from the West.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Russia’s transgender community is not large: just under 3,000 people, officially. But all those people’s lives have been cast into turmoil after Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a new law essentially banning transgender people in late July. They, and probably many more living in the shadows, will now be thrown into legal limbo.

“We are left with nothing,” says Nef Cellarius, an LGBTQ+ advocate. He says transgender Russians now find themselves virtual outcasts. “We cannot change our ID. We can’t obtain hormone or surgical treatments. This is a disaster.”

The new law seems to be an outgrowth of an ideological drive to create a unified “majoritarian” Russian society that’s been underway for about a decade. The war in Ukraine has greatly accelerated the official urge to differentiate Russia ideologically from the West while increasing the pressure to create a semblance of social unity behind the Kremlin.

“When you get down to it, how is Russia really different? Strong families? Many children? No. Our divorce and birth rates are European,” says researcher Irina Tartakovskaya. “Hence, we declare a different attitude toward LGBTQ people and the transgender community. They may develop normally in the West amid a tolerant attitude, but the situation in Russia is different.”

Anti-trans law leaves many Russians asking, ‘Who’s next?’

Russia’s transgender community is not large. Just under 3,000 people have officially changed their gender in an often lengthy and expensive procedure, overseen by a commission of medical and psychological experts.

But all those people’s lives have been cast into turmoil after Russian President Vladimir Putin signed a new law essentially banning transgender people in late July. They, and probably many more living in the shadows, will now be thrown into legal limbo, deprived of health care and official status.

The new law bans any kind of gender-affirmation surgery or hormone treatment and closes all previous avenues for a person to change their gender in official documents. It also annuls the marriage of any person who has transitioned and forbids them from adopting or acting as guardians to children.

“We are left with nothing,” says Nef Cellarius, coordinator of Peer-to-Peer, a consultancy for transgender and nonbinary people. He says it’s impossible to count the actual number of transgender Russians because many live in “stealth mode,” hiding in their previous gender or their new one, and now find themselves virtual outcasts. “We cannot change our ID. We can’t obtain hormone or surgical treatments. This is a disaster.”

The new law is a draconian departure from previous Russian legal practice and, some experts warn, a sign of things to come as the 18-month-old war in Ukraine accelerates Russia’s drift into political authoritarianism and social intolerance. Though far more sweeping in its harsh treatment of one beleaguered community than anything in the past, the law seems to be an outgrowth of an ideological drive to create a unified “majoritarian” Russian society that’s been underway for about a decade. The war has greatly accelerated the official urge to differentiate Russia ideologically from the West while increasing the pressure to create a semblance of social unity behind the Kremlin.

“A new state ideology positioned as conservative is being formed,” says Irina Tartakovskaya, an expert with the official Institute of Sociology in Moscow. “The basic idea is that Russia differs from the rest of the world, with different ideas and purposes. We declare respect for tradition and claim that the West has turned away from it. ... But when you get down to it, how is Russia really different? Strong families? Many children? No. Our divorce and birth rates are European. Men and women here behave much as they do in Europe. Hence, we declare a different attitude toward LGBTQ people and the transgender community. They may develop normally in the West amid a tolerant attitude, but the situation in Russia is different.”

“You are not protected”

Mr. Putin’s return to the Kremlin for a third presidential term in 2012, following a massive wave of public protests, is identified by many as the starting point for the hardening of Russian political culture and curbs on social diversity.

A new law banning public expressions of “nontraditional” sexual orientation was enacted, casting a chill over the country’s LGBTQ+ community by effectively outlawing public expressions of gay identity. Laws that compelled civil society groups to register as “foreign agents” if they received outside funding were introduced and progressively toughened. Last December, the anti-gay propaganda law was amended to ban any expression of “nontraditional” sexual identity on any media platform.

“During Putin’s first term, in the early 2000s, there was little effort to interfere with peoples’ personal rights. You had the feeling that you could live your life pretty much as you wished,” says Masha Lipman, editor of Russia Post, a journal of contemporary Russian affairs published by George Washington University. “But the relatively liberal atmosphere of the early Putin years culminated in mass protests and led to a hardening in the next decade.”

Many analysts say that Russia’s gay and trans communities have been targeted because they are small and relatively powerless, and the Russian majority tends to be socially conservative and receptive to such legal restrictions. A survey by Russia’s only independent pollster, the Levada Center, found in 2021 that a quarter of Russians believed that same-sex relationships between consenting adults were OK, up from 19% in 2015. However, the number of people who said they “do not support” such relationships grew from 58% to 69% between 2015 and 2021, while the number who found it “difficult to answer” dwindled from 23% to 7%.

Egor Kotkin, a socialist writer who is openly gay but careful about his lifestyle, says most of the people in his immediate surroundings have a “normal attitude,” but the atmosphere outside his social circle has definitely chilled since laws began to explicitly single out gay identity.

“If you were attacked by homophobes 15 years ago, and the police were called, they would protect you. Nowadays, the police would protect them,” he says. “It’s not a surprise that migration of LGBT people from Russia has greatly increased, especially since the war. We are second-class citizens here, and even if the law doesn’t specifically outlaw homosexuality, you know that you are not protected.”

The situation for trans Russians in the wake of the new law is far more dire.

“In the past, people could get hormonal treatment, occasionally surgery, and, if successful, they could get certificates and go on to change their official documents,” says Alexander Kondakov, an expert at University College Dublin. “That’s all abolished. Those certificates are now null and void. Overnight, people are stripped of their rights, denied health care, and returned to the status of pariahs.”

The war has intensified the social and political pressures upon Russians not merely to conform but also to view people with “nontraditional” characteristics as enemies.

“All the nasty things about this regime have been boosted. There is an effort to convince people that the West is working against us, targeting Russian society through influences like LGBT people, and it must be excluded from our midst,” says Ms. Lipman of Russia Post. “The ideological realm has become much more important over the past 18 months.”

Mr. Cellarius, who is also the program coordinator for LGBTQ+ rights group Coming Out, says the law is a template for future legislation that will target other groups. “You start with someone who’s invisible, as trans people are in Russia, and if people accept that, the list grows,” he says. “Nobody is safe.”

Podcast

Where once were shackles, a foothold for hope

At a place called ground zero for slavery in North America, our writer found a space for reflection about social progress that’s been haltingly made – and about the hard work still to be done. He spoke about his reporting on our weekly podcast.

Can a historical site of horror become a place of healing?

Writer Ken Makin traveled to the new International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, earlier this summer, and to the “hallowed ground” there at the site of Gadsden’s Wharf.

“In a lot of ways, it’s ground zero for chattel slavery in the country,” Ken says on the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast. “Forty to 48% of the enslaved who came into this country came in through Charleston.”

The museum does more than explain that hard history, Ken says. It honors the past, present, and future. Its role: to bring to the fore knowledge that has been tucked away. That isn’t easy.

“At the same time as people can attend this museum, there are also elements and entities and institutions who don’t want what’s in that museum taught in public schools,” Ken says. “And that’s very problematic.”

The museum also marks the cultural richness proudly nurtured in this region. Ken came across a woman who appeared deeply affected as she sat near a display. “And I asked her, you know: ‘Are you OK?’” Ken says. “She started to tear up a little bit. And so I just sat down with her, and we just talked. I’m gonna paraphrase what she said. She said: ‘We’ve been through so much; we’ve experienced so much, yet we thrive.’” – Clayton Collins and Jingnan Peng

Find links to related stories and a transcript here.

Honoring History on the Carolina Coast

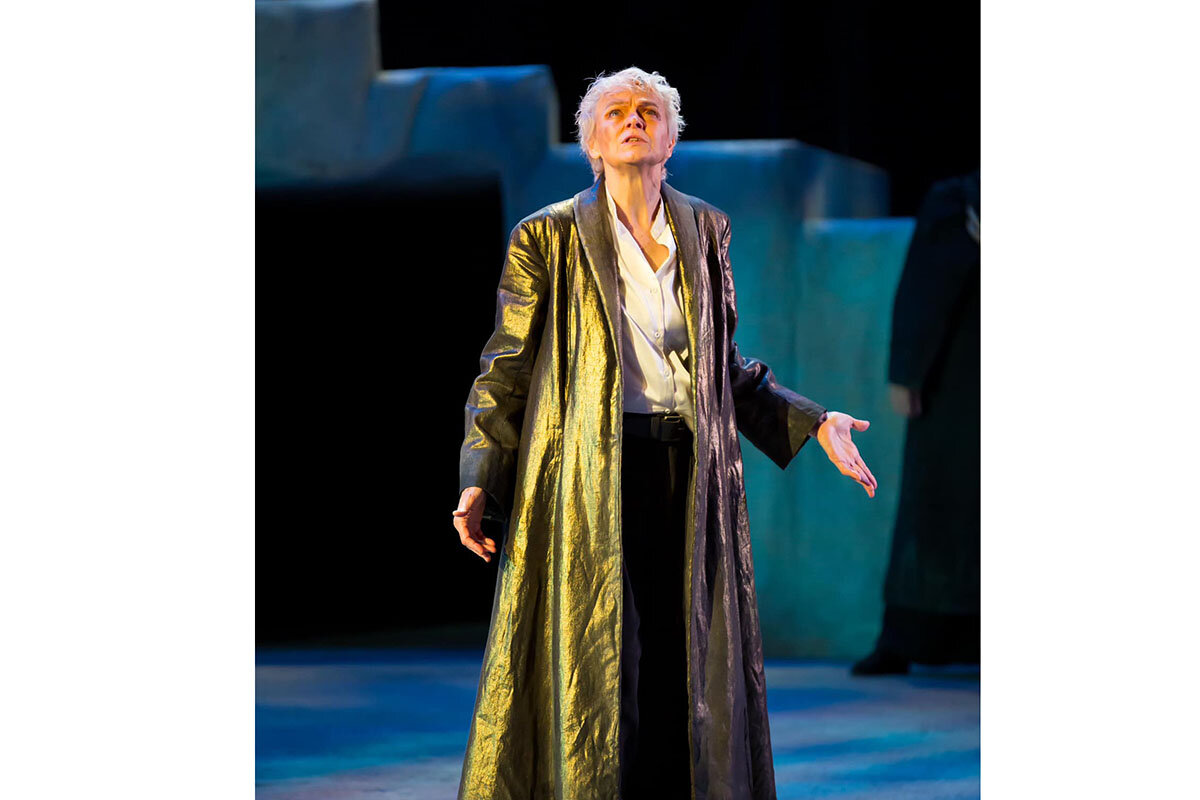

How one woman approaches iconic Shakespeare role

In “King Lear,” veteran actor Ellen McLaughlin has found both a “marvelous” role and a vehicle to help audiences consider how people care for one another.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Dean Paton Contributor

Despite her accomplished career onstage and as a playwright, Ellen McLaughlin was not prepared for the phone call from the artistic director of the Colorado Shakespeare Festival in Boulder asking her to take on the title role in “King Lear.”

She had multiple requirements for accepting the part: “We’re not changing the pronouns. I’m not gonna do it in a dress. It’s not Queen Lear. It’s not about the terrible things that happen when women get power,” she says. “If we do it right, there will come a point at which the audience will stop thinking about the fact that I’m not a man, and they’ll just watch an actor interpret a part.”

Ms. McLaughlin hopes the casting doesn’t overshadow what she insists is Shakespeare’s “biggest” play. “I don’t think he takes on these huge metaphysical questions in any other play,” she says.

What she learns anew each evening she plays Lear “is that you never know anyone’s story until you try to deeply understand,” she says. “There’s no dismissing any human being because we’re all carrying these sorrows that are ineffable and that rule us to some extent. So, I feel like it expands me as a human being to attempt to understand such a great and complicated character.”

How one woman approaches iconic Shakespeare role

When young Ellen McLaughlin was growing up in 1960s Washington, D.C., her parents would get dressed up – and get her dressed up, too – and take her to the iconic Arena Stage, which she calls “one of the first great regional theaters in America.” She saw masterpieces past and present: “Macbeth,” “Death of a Salesman,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” – and “King Lear.”

Though she now insists a 10-year-old has no business seeing a play with the madness and brutality of “King Lear,” she came out of that theater dreaming of someday playing Lear’s daughter Cordelia.

“And I did,” she says. But that was much later, after she’d become a professional actor. After she’d soared high over Broadway portraying the original Angel in Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Angels in America.”

Despite her accomplished career onstage and as a playwright – much of her extensive oeuvre has been produced around the world – she was not prepared for the phone call from Tim Orr, artistic director of the Colorado Shakespeare Festival in Boulder, asking her to take on the title role in “King Lear.”

“Tim offered me the part, and he said to me afterwards, ‘Did you realize that you took a full minute to respond?’” Ms. McLaughlin says in a Zoom interview. She’d had no memory of that. Nor had she any inkling, as Mr. Orr told her later, that he was “sweating like a pig” waiting, hoping she would agree to play Shakespeare’s most larger-than-life male character.

Still, she hesitated. “Before I can say anything, I need to talk to the director,” she told him. “I don’t want to be in a production where we’re not in sync on how to do this thing.”

In sync, for Ms. McLaughlin, entailed multiple requirements: “We’re not changing the pronouns. I’m not gonna do it in a dress. It’s not Queen Lear. It’s not about the terrible things that happen when women get power,” she says. “If we do it right, there will come a point at which the audience will stop thinking about the fact that I’m not a man, and they’ll just watch an actor interpret a part.”

Fortunately, director Carolyn Howarth had the same vision. She recalls brainstorming with Mr. Orr two years ago: “It’s a hard role to cast,” she says via phone. “So we talked about a bunch of people: male, female, actors of different ages. When we started, I didn’t start out saying, ‘I want to cast a woman.’ But boy, did I hit the jackpot with Ellen.”

“McLaughlin as King Lear fully embodies the character both vocally and physically, giving a fierce performance with non-stop conviction,” writes OnStage Colorado reviewer Eric Fitzgerald, calling her performance “a magnificent interpretation of the ultimate Shakespearean tragic figure.”

Ms. McLaughlin hopes casting a woman to play a male character won’t overshadow what she insists is Shakespeare’s “biggest” play. “Nothing else comes close. And that’s odd to say when you think about big plays like ‘The Tempest,’” she says. “Even ‘Pericles.’ But I don’t think he takes on these huge metaphysical questions in any other play.”

Lear is a “feeling, feeling” character, Ms. McLaughlin says, “much more so than many of Shakespeare’s female characters, and certainly more so than a character like Hamlet, who’s such an intellect.”

Ms. McLaughlin’s Lear is preyed upon by his emotions, “and he’s a character that desperately wants to be loved and yet doesn’t understand love at the beginning of the play.”

Shakespeare, she believes, is looking at “what is man when you strip the human of all attachments, all possessions, all identity. He loses his kingdom. He destroys his family. He loses his identity and he loses his mind.

“And there’s this truth that he finds out,” Ms. McLaughlin continues, “once he has lost everything – which is: What are we at essence? And what do we really want? What do we really need? What is it that he has been seeking and never understood – and that of course is love.

“And he’s redeemed by love.”

Yet, Ms. McLaughlin says, the character understood none of this until “Lear walks out into the storm and into homelessness and into countrylessness and into a lack of power and into annihilation. It’s the harsh education of a king. And learns too late what he could have done with the power that he had.”

The woman bringing Colorado’s Lear to life “absolutely” believes this play sizzles with contemporary relevance. “People in Shakespeare’s time knew something about the misery of the human condition and what it’s like at the bottom,” she says.

“We see it all around us,” she continues, referring to modern issues such as homelessness. “We don’t like to see it. So we don’t see it. But if we choose to actually pay attention to our fellow creatures and do something about it, a play like this – which is exquisite – opens the heart to that level of compassion, which is necessary to do something effective to address the suffering of the world.”

Lear’s life is pure tragedy, yet the play concludes with a sliver of hope, “because Edgar, who becomes king at the end of the play, learns in time the lesson that Lear learns too late – which is to pay attention to the people who are your responsibility,” Ms. McLaughlin says. “If you’re the king, these are the people whose lives are in your hands.”

Despite the age-old themes of this play, the novelty of casting Ms. McLaughlin as a brute of a man arrives at a time of increased legislation banning drag performances and of parents challenging libraries over books discussing gender identity or sexual orientation.

In Houston, in April, a school district canceled an elementary school’s field trip to see a stage version of Roald Dahl’s “James and the Giant Peach” after some parents complained that male and female actors would perform roles of different genders. Those parents insisted this made the production a drag show.

“As a nation, we’re experiencing extreme polarity around gender fluidity, and casting a woman in a male role gets lumped in with that,” says Heidi Schmidt, who is on the faculty at the University of Colorado Boulder and is the dramaturge for the festival’s “King Lear” production.

Pointing out that it was illegal in Shakespeare’s England for women to act in the theater, she says, “The original Juliet was male. The original Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia were all males. Peter Pan was played by a woman for generations, and nobody was bothered by that.”

Ms. McLaughlin adds that it was “very cutting edge” in the 1960s to cast African Americans in traditionally Caucasian roles. “There was no Black King Lear. And now it’s just commonplace to have Black people playing those parts, and I think the same thing is gonna be happening with gender.” (Indeed, British actor Glenda Jackson played the tempestuous monarch at London’s Old Vic in 2016 and reprised the role on Broadway in 2019.)

Ms. McLaughlin thinks of the play as being about power rather than about masculinity. “The play’s about patriarchy. The play’s about fathers and daughters, and his fundamental dilemmas and his fundamental revelations and joys have to do with the human tragedy and the human experience – and I feel I’m perfectly capable of doing that,” she says.

Dr. Schmidt put it this way: “We’re not saying anything about Ellen’s identity. We’re not saying anything about Lear’s identity. We’re just casting a great actor in a great role.”

Ms. McLaughlin says she’ll never have a part this marvelous again. “There just isn’t a part this good, and I don’t want to stop playing him,” she says. “I would do this for the rest of my life. It’s a part that you’ll never get right. It’s like trying to throw a no-hitter, you know? You’re never gonna do it. But the effort to do it is worthwhile, and you learn something from that effort.”

What she learns anew each evening she plays Lear “is that you never know anyone’s story until you try to deeply understand. There’s no dismissing any human being because we’re all carrying these sorrows that are ineffable, and that rule us to some extent,” she says. “So I feel like it expands me as a human being to attempt to understand such a great and complicated character.”

“King Lear” runs through August 12 at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival’s Mary Rippon Outdoor Theatre in Boulder.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Democracy’s art of washing feet

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

At a time when political grievances are testing norms and institutions in countries like Israel, India, and the United States, some democracies are finding resilience in the practice of respect and humility.

Spain’s recent elections show a decline in support for secession in the region of Catalonia, perhaps reflecting conciliatory gestures by the government. French President Emmanuel Macron has gone on listening tours in response to mass social protests over fuel prices, taxes, and retirement reforms. In India, banned opposition leader Rahul Gandhi walked the country’s length “to stand up against the fear, hatred and violence that is being spread in the country.”

In June, Chile launched a new Commission for Peace and Understanding to address the long-standing Indigenous grievances over land rights. The new panel rests on an acknowledgment of historical wrongs as a basis for building trust.

“We all come together from different visions [and] daily political quarrel,” said President Gabriel Boric, “putting the common good above our differences.”

Democracy, writes Harvard Business School professor David Moss, “needs to actively work against corrosive forces, both moral and institutional, or succumb to them.” From Spain to Chile, societies are finding a restorative power in words spoken softly.

Democracy’s art of washing feet

Since its elections nearly two weeks ago, Spain has been stalled. The two main parties each fell just short of a majority in parliament, which one or the other needs to form a new government. But buried in the ballot’s footnotes is a lesson for countries striving to heal the sharp divisions of political grievance.

The region of Catalonia in Spain’s northeastern corner has a long history of secessionist discontent. Six years ago, it held a referendum to break away. The Spanish government responded with police force that human rights watchdogs called excessive. Lately, however, Madrid has struck a more conciliatory tone. Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez pardoned nine separatist leaders in 2021 in what he called a “constitutional spirit of forgiveness.” In January, he signed a law striking sedition – the crime for which the nine were imprisoned – from Spain’s penal code.

Those gestures help to explain one outcome in the recent election. “Catalan national parties performed rather poorly in this election,” noted Carlota Encina, a Europe expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, while “the very respectable voter turnout, over 70 percent, above the EU average, suggests that Spaniards have considerable faith in their representative institutions.”

At a time when political grievances are testing norms and institutions in countries like Israel, India, and the United States, some democracies are finding resilience in the practice of respect and humility.

Twice during his administration, French President Emmanuel Macron has gone on listening tours in response to mass social protests over fuel prices, taxes, and retirement reforms. In India, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has done the same. He recently walked the country’s length listening in response to political violence and new restrictions on the religious minorities. The aim, he said, was “to stand up against the fear, hatred and violence that is being spread in the country.”

The South American country of Chile is trying its own experiment in accommodation. In June, the government launched a new Commission for Peace and Understanding to address the long-standing Indigenous grievances over land rights. A previous administration deployed soldiers in response to violence in Mapuche strongholds and imposed a state of emergency. The new panel rests on an acknowledgment of historical wrongs, including dispossession and ethnic pogroms, as a basis for building trust.

“We all come together from different visions [and] daily political quarrel,” said President Gabriel Boric, “putting the common good above our differences.”

Democracy, writes Harvard Business School professor David Moss, “needs to actively work against corrosive forces, both moral and institutional, or succumb to them.” From Spain to Chile, societies are finding a restorative power in words spoken softly.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Getting all my questions answered

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Susan McCandless

Learning about spiritual reality brings a deeper trust in God and greater certainty in our path forward, as a young woman experienced firsthand after being introduced to Christian Science.

Getting all my questions answered

I was raised in a mainstream Christian religion and went to church and Sunday School with my family every week. But when I was in high school, I began questioning what I understood about God and my relationship to Him. I yearned to know if God really existed.

I wondered, Did God create man, or did man create the concept of God in order to explain long-held beliefs and traditions? If God exists and loves me, as I’d been taught in Sunday School, why do bad things happen? Does God punish me when I’m “bad” and reward me when I’m “good”?

In search of answers to these questions, I took every opportunity to visit other church denominations with friends, and I also began reading books on spirituality.

By the time I got to my sophomore year of college, I felt lost. I had no idea what I wanted to do with my life. I did know that I wanted to transfer to a different college. But either the schools I applied to didn’t accept me or I felt they were a wrong choice for one reason or another.

That spring, I met a girl my age through a mutual acquaintance. When I discovered that this new friend was a Christian Scientist, I peppered her with all sorts of questions about her faith. Although she’d been raised in Christian Science and did her best to explain, she felt my questions might be better answered by my going to church with her.

At first I declined, thinking I knew all I needed to know about this religion, based on what she’d told me. But eventually my curiosity got the better of me, and we attended a testimony meeting together.

As I sat in the church that evening, listening first to the comforting passages from the Bible and then the deeply inspiring readings from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, I felt I had come home. But it was the sincere, joyful testimonies shared by other attendees that made me realize that Christian Science was what I’d been searching for.

It was more the feeling I got from hearing those testimonies than the specific words or healings that were shared. I felt joyful, honest gratitude for God and His guidance. I also sensed a profound trust in God, something I myself had never felt. All those who testified sounded like they really knew God, Love, and trusted Him in all aspects of their lives. Afterward, I stayed to speak with members, who were more than happy to share their insights and thoughts about Christian Science with me.

The next day, I went to a local Christian Science Reading Room, and the attendant patiently explained how to read the weekly Bible Lesson found in the “Christian Science Quarterly.” She even gave me an old copy of the King James Version of the Bible and a copy of Science and Health for my very own. I was so grateful, and this began my journey of discovering more about my relation to God and how to live and apply Christian Science in my own life.

I was like a sponge, soaking up as much as I could about this entirely spiritual view of existence. It answered my questions simply but in an absolute way, which made me want to understand more about God and healing.

Soon after my visit to the Reading Room, I decided to apply to a college for Christian Scientists. I was accepted, and when I couldn’t pay the tuition, my financial needs were met quickly and harmoniously as I trusted all the details to God. My last two years of college were filled with spiritual inspiration, happy friendships, and an excellent education, which eventually led me to a successful career.

I am deeply grateful that I was introduced to Christian Science, which has blessed my life immeasurably.

Originally published in the Christian Science Sentinel’s online TeenConnect section, May 23, 2023.

Viewfinder

(Almost) totally classic

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us today. Come back Monday, when we’ll have a deeply reported story on Turkey’s recovery from February’s devastating earthquakes.