- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

School starts, but absenteeism is rising

Jackie Valley

Jackie Valley

School bus engines are rumbling, and parents are posting sentimental first-day photos, signaling the start of another academic year.

It’s back to class for thousands of children across the United States, with more start dates in the coming weeks. Inevitably, this time of year conjures hopeful feelings of fresh starts and endless opportunities. New teachers, new friends, new knowledge.

The fruits of the academic experience, however, rely on students actually being in school. And that’s the problem. More than 1 in 4 students were considered chronically absent during the 2021-22 school year, according to data compiled and analyzed by Thomas Dee, an education professor at Stanford University, in partnership with The Associated Press.

The analysis examined data from 40 U.S. states and Washington, D.C., giving a robust national portrait of chronic absenteeism, defined as students missing 10% or more of school days. Before the pandemic, in the 2018-19 academic year, about 15% of students missed that much school. But the rate grew to 28% during the 2021-22 school year. That’s 6.5 million more students, Dr. Dee says.

In two states that have released more recent data, the problem has persisted.

“What I found was that the state-level growth in chronic absenteeism was actually unrelated to a measure of COVID infection rates over this period,” Dr. Dee said during a media call earlier this week.

That means other factors are at play. Could students’ fragile mental health be causing them to miss school? Or have they simply lost the desire to attend classes?

These are questions that educators, researchers, and – yes – even journalists will be exploring as a new school year unfolds. Most problems in the education realm don’t yield simple answers. Instead, nuanced reasons typically explain troubling trend lines.

We’re here to help tell that story and look toward solutions. Please drop me a line if you know people – students, parents, school staff members, or others – who are taking steps to boost classroom attendance and, in turn, brighten the next generation’s future. My email is valleyj@csmonitor.com.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why a US-Ukraine space project has drawn to a close

A little-known but fruitful partnership in space between the United States and Ukraine has come to an end, a victim of the war with Russia. But the Antares program has left warm memories on both sides.

Outwardly, the launch last week of another Antares rocket carrying a payload to the International Space Station was routine. It went perfectly, and there were cheers and hugs all around at NASA’s facility on Wallops Island off the coast of Virginia.

But it was special, and sad, for the Ukrainian engineers and space scientists on hand. This launch was the last in a series of 18 over the past decade to be powered by a Ukrainian first-stage rocket.

Ukraine’s first stage for Northrop Grumman’s Antares rocket is powered by Russian engines. A Russia at war with Ukraine is refusing to provide those first-stage rockets any longer.

“Certainly there is regret and sadness that this biggest of international projects for us is coming to a close,” says Anatolii Agarkov, a chief adviser to the director general of Yuzhnoye, Ukraine’s state-owned designer of satellites and rockets.

But other reasons beyond the war explain the demise of the little-known U.S.-Ukrainian project.

“Over the last decade, we’ve seen a resurgence of nationalism,” says Joshua Valentine, a Northrop Grumman electrical engineer, and countries have turned away from international cooperation.

Still, everyone involved in the project agrees on one thing: Ukraine’s cooperation with the United States on the Antares rocket has benefited both sides.

Why a US-Ukraine space project has drawn to a close

Amidst the whoops and applause that cheered the Antares rocket as it rose from NASA’s Virginia seaboard launch facility one evening last week were the hugs and thumbs-ups exchanged by Ukrainian aerospace engineers and officials with their American counterparts.

The faultless launch of a payload destined for the International Space Station marked more than a decade of U.S.-Ukrainian cooperation on the Antares program, with Ukraine providing the first stage of the workhorse rocket.

“This launch was so perfect; it makes all of us from Ukraine so proud of our years of work with our American friends,” says Dmytro Nikon, chief economist with the Ukrainian aerospace manufacturer Yuzhmash.

Yet the triumph of the launch, the 18th with a Ukrainian first-stage core, was overshadowed by the reality that it was also the end of the road for Ukraine’s participation in the Antares program.

“Certainly there is regret and sadness that this biggest of international projects for us is coming to a close,” says Anatolii Agarkov, a chief adviser to the director general of Yuzhnoye, Ukraine’s state-owned designer of satellites and rockets. “Working so long with the U.S. expanded our international horizons,” he goes on, “but sadly the war has scuttled all that.”

Why the flagship of U.S.-Ukraine space cooperation would be ending even as many other facets of the two countries’ relationship are expanding has one obvious explanation: Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Ukraine’s first stage for the Antares rocket is powered by Russian engines. A Russia at war with Ukraine is refusing to provide those first-stage rockets any longer, and when the Ukrainians were unable to come up with replacement engines, Northrop Grumman – the New York-based aerospace company that makes Antares rockets – canceled its contract for two more first stages.

No Russian engines, no Ukrainian first stage, at least for the time being.

But a number of broader forces have also undermined the joint project, ranging from the commercial space industry’s shift to lucrative military applications, to a global trend away from international space cooperation to more nationalist programs and the militarization of space.

The shift is evident in the Antares program.

Northrop Grumman, a commercial resupplier for the International Space Station, wants to grow military contracts as a share of its business. But the Pentagon restricts most of its contracts to domestic suppliers.

Thus Northrop Grumman is now working with Austin-based Firefly Aerospace to provide it with new space components, including a first stage for Antares.

The irony of that partnership is that Firefly was built by a Ukrainian billionaire, Max Polyakov, who had hoped to develop a world-class commercial space company drawing on U.S. and Ukrainian strengths. But Mr. Polyakov saw his dream shattered last year when he was forced to sell his interest in the company because of U.S. government concerns that his ownership posed national security and technology-transfer risks.

Working with Firefly, Northrop Grumman has now set an all-American Antares launch for 2025.

Still, despite a trace of sadness underlying the joy of a successful launch, everyone involved in the project agrees on one thing: Ukraine’s cooperation with the U.S. on the Antares rocket has benefited both sides.

Ukraine’s state-owned aerospace companies have learned the ropes of the competitive commercial space industry, people here say, and the U.S. has had access to Ukraine’s top-quality (though somewhat outdated) space technology, a scion of the Soviet space program.

“All along the way, the Americans have shown respect to our knowledge and practical experience,” says Mr. Agarkov. Noting that the learning has “gone both ways,” he adds with a smile that “the system we come from had very strict rules and did not encourage innovative thinking. From our American friends, we learned to be much more open to innovation.”

For the Ukrainian staff on-site in Virginia, the launch was a bittersweet moment.

“On one hand, of course, we all feel disappointed that this experience and time-tested project had to stop,” says Oleksandr Iatsun, chief of the telemetry team and measurement systems for Yuzhnoye. “But on the other hand, it’s been a very positive and enriching experience,” he adds, “so I’m cautiously hopeful for the future. We’ve made the progress to march on.”

An engineer who has been part of Ukraine’s involvement with the Antares program since the collaboration began in 2009, Mr. Iatsun highlighted the benefits he, his company, and Ukraine have reaped from the cooperation with the U.S.

Antares “wasn’t the first example of international space cooperation for Ukraine,” he says, but “here there has been a level of integration and interfacing of systems that was a new challenge for us ... one we’ve learned from.”

One “big plus” he sees from the decade of Ukraine’s involvement with Antares launches is that a new generation of Ukrainian aerospace engineers has developed expertise with a Western orientation, less influenced by the Soviet roots of Ukraine’s space program.

“My early experience in my career was with Russia,” he notes, “but the younger guys have learned and now follow Western protocols. I think that will serve us well in the future.”

The Americans who have worked on Antares spoke in equally glowing terms of their experience with the Ukrainians and said that they learned just as much from them.

“The Ukrainians taught me to methodically work through everything,” says Patrick Hoar, who oversaw the Ukrainians’ retooling of their highly successful Zenit rocket to provide the Antares first stage. “I learned there’s an efficiency in doing everything right, right away.”

Perhaps most impressive, several Americans said, was how the Ukrainians carried on despite Russia’s war on their country. “Their resilience is astounding,” says Joshua Valentine, Northrop Grumman’s electrical lead at Wallops. “We all could learn from their ability to focus on our mission’s success in the face of what’s happening in their homeland.”

Both teams cite Russia’s war as the direct cause of the end of Ukraine’s participation in the Antares program. There is a shared frustration that Russian President Vladimir Putin appears to be achieving one of his goals: weakening, if not destroying, Ukraine’s economic vitality.

But other forces, too, have worked against the collaboration.

“Over the last decade, we’ve seen a resurgence of nationalism,” says Mr. Valentine, as countries turned away from international cooperation, “prioritizing their security fears. ... We see the impact of that in space programs around the world.”

Indeed this militarization of space programs is evident to some degree in Ukraine.

The Ukrainians at Wallops acknowledged that the war has prompted a certain redirection of the country’s aerospace industry, but beyond acknowledging their army’s effective use of satellites, they were reluctant to give any details.

But mostly, the Ukrainians are adamant that the world should see their country in a new light.

“Of course, the war has been terrible, but that is not all Ukraine is,” says Mr. Iatsun, who has been in Virginia since September of last year. “In a small way, because of this program, the world is learning that Ukraine is not just the war or a source of grain,” he adds, “but a country with a top space program that will have an international presence for many years to come.”

That faith in the future pervades the Ukrainian Antares team.

“That this is the last launch for us, I accept it – all good things must come to an end, as they say,” says Vadym Demchenko, deputy program manager of Yuzhnoye’s Antares program.

“And usually,” he adds with a smile, “the end of something also means the opening of a new chapter. I think we’re all hopeful and excited about that.”

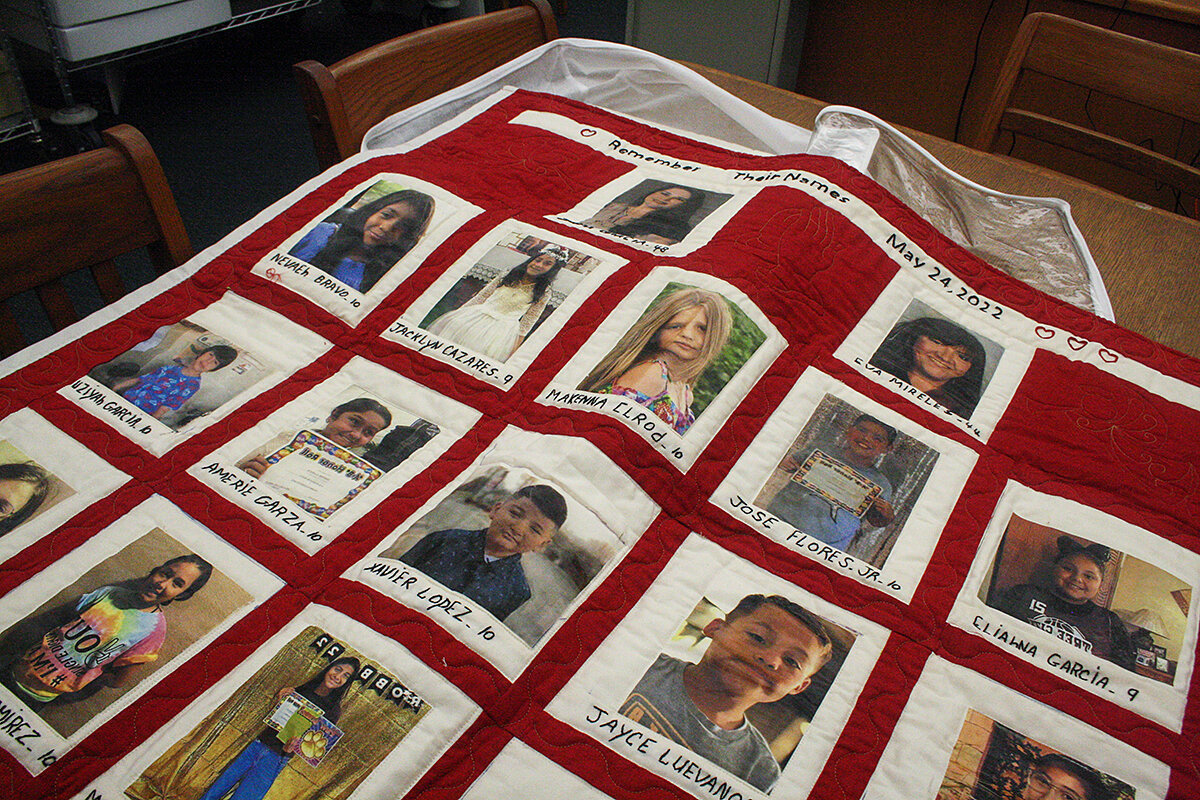

A ‘tunnel of love’: Uvalde library offers healing

The public library in Uvalde, Texas, is documenting the “outpouring of love” after the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School last year, helping the town to process and heal.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

In the days after the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, last year, messages of love and support flooded in from around the country. The public library seemed a logical place to send all of them.

But the library wasn’t sure how to handle the items. It settled on starting an archival project, which aims to preserve the national response to the tragedy – and help residents and visitors learn more about Uvalde.

Tammie Sinclair, a Uvalde native, returned home to lead the project this year. She’s been archiving thousands of cards, gifts, and newspaper articles and is helping to start an oral history project that will be run out of the library.

As Uvalde continues to heal after the shooting, Ms. Sinclair’s work aims to highlight the flood of love and support that has followed the devastating event. In the long term, the goal is to help Uvalde learn more about itself – and grow as a result.

“There’s a lot of ugly that came out of [the shooting] – not just the tragedy itself, but the aftermath,” she says. “But it’s what you choose to focus on, and we’re trying to focus on the good.”

A ‘tunnel of love’: Uvalde library offers healing

When Tammie Sinclair needed some peace and quiet growing up in a crowded, three-generation household, there was only one place to go. The public library was her sanctuary, her escape, even her summer camp.

And for the past year, El Progreso Memorial Library has been her workplace. She hopes her work here will benefit her hometown for generations.

Since January, the Uvalde native and former teacher has been leading a grant-funded program to archive the national response to the mass shooting at Robb Elementary School last year. She and a small group of volunteers have been archiving thousands of cards, gifts, newspaper articles, and more from the aftermath of the tragedy. She’s also helping to start an oral history project that will be run out of the library, and she’s helping plan the physical expansion of El Progreso to better house all of it into the future.

As Uvalde continues to heal after the shooting, Ms. Sinclair’s work is aiming to highlight the flood of love and support that has followed the tragedy. And in the long term, the aim is to help Uvalde learn more about itself – and grow as a result. In her view, there’s no better place to do all this than a public library.

“This is one place in the community where anybody is welcome,” says Ms. Sinclair. “We want to be a place of hope and education.”

“There’s a lot of ugly that came out of [the shooting] – not just the tragedy itself, but the aftermath,” she adds, “but it’s what you choose to focus on, and we’re trying to focus on the good.”

Library a “critical part of the healing and the coping”

For much of its 120-year history, El Progreso has been more than just a library. Since the shooting, it’s played an important role in supporting Uvalde, providing both services and a sense of normalcy.

Within days of the tragedy, the library hosted craft therapy workshops and a mental health symposium. In later months, events geared toward helping children maintain routines and process their feelings – including book readings, musical performances, toy giveaways, bilingual counseling, and drumming circles – have followed.

“I don’t know what the town would do without the library, to be honest,” says Michael Robinson, a former member of the library’s board who owns a local news site, the Uvalde Hesperian.

“Our library is not your typical ‘check out a book and get a computer’ library,” he adds. “It’s been a really critical part of the healing and the coping with the tragedy.”

Since the mass shooting, messages of love and support had flooded in from around the country. Cards, letters, and gifts – often addressed, simply, to Uvalde – arrived at the post office, City Hall, even Robb Elementary itself.

But what to do with all of them? Surely the public library would know where to keep everything, and how to organize it?

Thus, El Progreso became Uvalde’s unofficial post office. And Ms. Sinclair – a newly minted librarian – became an archivist. She did her state-mandated librarian training here late last year, and then she kept coming back even when living in San Antonio. She knew she wanted to be a library director, or work with teens, but then the archivist position came up.

“I’d always wanted to kind of give back to my community and be a librarian,” she says. But the idea of returning to her hometown and being the project’s archivist “just kept tugging at my heartstrings.”

“I thought, ‘I think I have to do this,’” she adds. “So I applied. And here we are.”

The job, funded with a 12-month grant through the National Endowment for the Humanities and Humanities Texas, began in January. A crash course in archival best practices later, and Ms. Sinclair has the archives for the “Los Angelitos de Robb” project on a solid footing.

Over 2,000 unique items – from condolence cards, to quilts, to handcrafted wood cutouts of the 21 victims of the shooting – have been cataloged and stored. Local, state, and national newspaper coverage of the response has been archived as well. Not everything can be preserved, such as gifts left in town at outdoor memorials, but they’re still processing boxes of cards and gifts received in the immediate aftermath of the shooting.

“I hope it will be healing and comforting to people to see this enormous outpouring of love that has come in the wake of this evil,” says Mendell Morgan, the director of the library.

For the first anniversary of the shooting, staff used hundreds of cards in its collection to create a “tunnel of love” at the entrance to the library. Copies of sympathy cards that have already been archived are left on shelves at the library entrance for people to take.

Uvalde’s rich history

The library has always been a place of comfort and learning for Ms. Sinclair, and she wants it to be that for the rest of Uvalde as well.

She was a struggling reader growing up, but she struggled even more at sports. Under no circumstances was she going to sports camp in the summers, so she would come to the library with her mother.

“I just fell in love,” she says. “I always felt welcome.”

Like many children raised in a small town, however, she grew up wanting to leave. And despite all the time she spent at the library, she never learned much about her town – not until she came back to work there.

Some may know Uvalde as the birthplace of actors Matthew McConaughey and Dale Evans, or politicians John Nance Garner (a vice president) and Dolph Briscoe (a Texas governor). But the town was also once the “honey capital of the world” (producing 1.5 million pounds per season, according to one early-20th-century news report), and the site of a student walkout seminal to the 1970s Chicano Movement.

Ultimately, Uvalde had a rich history long before tragedy struck last year. And while the project is focused right now on preserving the response to the devastation at Robb Elementary, Ms. Sinclair, and the town, hope it will come to focus on that rich history.

Part of the grant, for example, is for an oral history project, recording and preserving interviews with people about the tragedy. “The hope is that it will [start] with the tragedy, but then expand,” says Ms. Sinclair. Eventually, El Progreso could “become a regional repository for oral histories.”

“We weren’t on the map” prior to the shooting, says Diana Olvedo-Karau, who was born and raised in Uvalde and moved back five years ago.

“My hope is that the tragedy is not going to define Uvalde. We are so much more than that,” she adds.

To achieve this, the library is looking to physically expand. The existing archives have been outgrown, and Ms. Sinclair says they want to build a bigger meeting room for community members, as well as a space that’s more teenager-friendly. They also want to continue offering all the free events and services they’ve made room for over the past year, such as a grief counselor who still holds weekly in-person sessions at the library. Funding for a new children’s wing will come from an endowment that’s starting with $76,000 the library has received from donors around the country after the shooting, according to the San Antonio Report.

All told, if there’s one place that can continue to help Uvalde heal and be a part of how the community grows out of the tragedy, it’s a place where everyone is welcome. It’s a library, supporters say.

“We’re a cooling center in the summer and a warming center in the winter,” says Ms. Sinclair. “No one’s turned away here.”

“Any given day you could come in, and some different program is happening,” she adds. “That is what is key here. ... You can reach people in so many different ways.”

Podcast

How good data deepens understanding

Integrity earns trust. The work of a Monitor graphics designer is to inform, not to persuade. That means sifting for stats that can help readers make up their own minds about complex stories, and sharing them with clarity.

A clear presentation of quality data can make a complex story digestible. The right set of charts can be the basis of greater understanding.

Data visualization calls for smart digging and artful displaying. Those are two of Jake Turcotte’s main jobs at the Monitor.

“Looking for good data is a process,” says Jake, a multimedia editor and director of graphics. “What we’re really looking for is primary source data. That is the gold standard for us.” That means mining the output of trusted institutions and sometimes casting a wider net. It demands care.

“Sometimes data sources come with their own caveats,” Jake says on the Monitor’s “Why We Wrote This” podcast. “The people who put it together, you know, what’s their motive? Is it informing, or is it convincing?”

In telling honest stories, context matters. For example, “it’s become a popular idea that America’s cities are more and more dangerous,” Jake says. That’s supported by a five-year view. Zoom back, however, and you can see a decline from an early ’90s peak.

“What we’re trying to give readers is a toolbox that they can use to understand the world,” Jake says, “and to refute arguments that are made dishonestly.” – Clayton Collins and Jingnan Peng

You can find show notes with story links and a transcript here.

Where Disinformation Gets Destroyed

Ukraine cafe serves soldiers free food, motherly love

When is a roadside cafe more than a roadside cafe? When it’s in Ukraine, and the service runs from free borscht to restoring wounded soldiers’ will to live.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

From the road, Nataliia Bilovol’s cafe looks like any other pit stop in eastern Ukraine. In fact, it is anything but ordinary.

Inside, volunteers work three shifts a day cooking and serving 2,500 free meals to the constant flow of soldiers, ambulance drivers, and emergency workers heading to the front or returning from it.

On this road to war, the cafe has become a sanctuary, renowned not only for the sustenance of its home-cooked food and as a place to rest, but also for the loving motherly care offered by Ms. Bilovol and her 70-strong team of volunteers.

Sometimes that means just a friendly hug for a soldier they have seen at the cafe before.

Sometimes it can mean much more, like restoring a wounded man’s will to live.

But life is not always that intense at the cafe. More lighthearted moments enliven the place.

One recent day, as a group of soldiers walked out after a filling meal, volunteer server Nelya Shaykhutdynova stopped making coffee for a moment and approached the last man to leave. “At least take some pie in your pocket,” she implored him.

He didn’t need any persuading.

Ukraine cafe serves soldiers free food, motherly love

From the road, the unassuming building looks just like any other pit stop in eastern Ukraine, with sacks of onions and large jars of pickles piled up against log-cabin walls.

Dust swirls as vehicles pass by. A recovery vehicle towing a military truck shudders noisily to a stop on the dirt verge, so the drivers can get a bite to eat.

But this cafe is anything but ordinary. Inside, volunteers work three shifts a day, cooking and serving free meals to the constant flow of soldiers, ambulance drivers, and emergency workers heading to the front or returning from it.

On this road to war, the cafe has become a sanctuary, renowned not only for the sustenance of its home-cooked food and as a place to rest, but also for the loving motherly care offered by Nataliia Bilovol, the cafe owner, and her team of volunteers.

“Every time we see a person come back again, we are so happy to see them alive,” says Ms. Bilovol, who wears an olive drab polo shirt emblazoned with patch strips that read “volunteer” and “combat.”

“Every time we see them again and again, their hugs get stronger and stronger,” says Ms. Bilovol of the soldiers’ reaction. “They tell us, ‘With backing like this, we are able to fight properly. Ladies, please have our backs, and we will hold the defense.’”

Memories, sweet and sour

When Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, Ms. Bilovol closed her cafe. But as soldiers deployed to the eastern front lines to block the Russian advance, they stopped off for supplies at her shop next door.

She and other volunteers began to give the troops coffee on their buses. Then a table was brought outside to serve borscht, the savory Ukrainian beet soup with dill and sour cream.

Today the cooking area has cabin-style log walls, where volunteers peel endless supplies of potatoes and onions, and vats of mouth-watering soup and stew simmer on gas and log-burning stoves.

In the dimly lit cafeteria itself, where the scent of dill and pickled vegetables is a strong reminder of a typical Ukrainian kitchen, the one long table is constantly laden with food. The cafe serves some 2,500 free meals a day, surviving with the help, in cash and kind, of donors near and far – from local villagers who bring food to distant supporters in Europe and the United States.

The respect and gratitude of those who pass through are clear from the walls, which are draped with yellow and blue Ukrainian flags signed by soldiers and pinned with a multitude of military unit patches.

At one end of the canteen, Orthodox religious icons share space with battlefield artifacts, including the rear plate of a U.S.-supplied HIMARS rocket, expended tank shells, and the skeletal frames of Russian cluster munition canisters.

It is as if the whole war has funneled its way through here. And that means that Ms. Bilovol and her 70 or so volunteers share all the emotions of the men they sustain.

“It’s always hard to remember all the wounded soldiers” who do not return, says Ms. Bilovol. But some memories bring a smile, such as the soldier she fed in his ambulance parked outside because his leg wounds prevented him from walking.

“He kept asking what the place looked like, and I showed him pictures of it on my mobile phone. He ate and promised that he would definitely come back,” recalls Ms. Bilovol.

When he did, he was returning to fight on the eastern front. “He stood up on his legs and hugged us and thanked all of us for the help and the warmth we gave him,” she says, her eyes welling up. “That was such a powerful emotional moment for all of us.”

Restoring the will to live

Among the volunteers is a retired school secretary, Valentyna Lushchynska, who wears a bright green shirt and head wrap, an embroidered black apron, and a mischievous smile. She started working here the very first day the canteen opened.

“I took everything from my cellar,” says Ms. Lushchynska of her first donations. “And all the neighbors said, ‘We’ll be killed anyway, so take our chickens and supplies too.’

“It’s very hard work, so a lot of people have left this job already. But I am an old one; I am tough,” says the pensioner.

“People ask, ‘Why do you keep coming here?’ I tell them, ‘It’s like the call of my soul.’ The gratitude of the soldiers is like a gold medal on this side and a gold medal on that side,” she says proudly, pointing to each side of her chest.

She recalls feeding one soldier who had lost one arm and one leg, and had not eaten for four days.

In his ambulance, he pulled her close to express his thanks, she remembers, and said, “I want to kiss your hands because I had a black curtain blocking my life. When I saw you, with your warmth, from that moment I wanted to live again.”

Life is not always that intense at the cafe. More lighthearted moments enliven the place.

On one recent day, the soldiers in charge of the recovery vehicle that had pulled over, pistols on their hips, were enjoying a hot lunch and explaining why they come regularly. “The food is delicious,” said one man who gave the name Zhenia. “The food is like home.”

Volunteer server Nelya Shaykhutdynova stopped making coffee for a moment as the last soldier left. “At least take some pie in your pocket,” she implored him.

He didn’t need any persuading.

Oleksandr Naselenko supported reporting for this story.

In Pictures

It’s a bug’s life. We’re just along for the ride.

By promoting a bug’s-eye view, the new wing at the American Museum of Natural History challenges our preconceived notions of scale and significance.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

Alessandro Clemente Staff writer

In a single strip of turf, insects see a towering forest with hidden passageways. What may seem insignificant to us is a thriving universe for them.

The insectarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York brings a bug’s perspective home to us humans, who walk in as giant visitors.

The star attraction is the ant colony. Ants are sophisticated farmers who create sprawling fungal gardens, nourished by leaves they can only obtain through cooperation. Slowly but surely, the ants navigate their way over skybridges, up poles, and across moats, adapting and learning as they explore.

The insectarium, part of the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, challenges our preconceived notions of scale and significance. It allows us to contemplate the incredible diversity and complexity of insect life.

Most importantly, it reminds us that every living organism, no matter how small, plays a vital role in the grand tapestry of life on Earth.

It’s a bug’s life. We’re just along for the ride.

In a single strip of turf, insects see a towering forest with hidden passageways. What may seem insignificant to us is a thriving universe for them.

The insectarium inside the newly opened Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation at the American Museum of Natural History in New York brings this perspective home to us, the giant visitors. It allows us to contemplate the incredible diversity and complexity of insect life.

The star attraction is the ant colony. Ants are sophisticated farmers who create sprawling fungal gardens, nourished by leaves they can only obtain through cooperation. Slowly but surely, the ants navigate their way over skybridges, up poles, and across moats, adapting and learning as they explore.

“We are studying how to maintain the colony,” says James Carpenter, curator of invertebrate zoology at the museum. Visitors “seeing the ants foraging and caring for their fungus garden is the goal.”

By promoting a bug’s-eye view, the museum’s new wing challenges our preconceived notions of scale and significance. It reminds us that every living organism, no matter how small, plays a vital role in the grand tapestry of life on Earth.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Hollywood strikes an opening chord for unity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The union representing screenwriters, and the studios that turn their words into films and television shows, have agreed to restart formal negotiations to end a strike that has stalled the entertainment industry all summer. Those talks were set to begin today.

The dispute has already cost California’s economy $3 billion, according to one estimate. But it has also surfaced qualities of thought that may guide Hollywood through a transition that is about profoundly more than labor contracts.

The strikes are “not merely about better pay, improved working conditions, and regulations on AI use, but rather, a potent call for the recognition of human dignity and artistic integrity,” wrote Wilbur Greene, an Australian editor and literary agent. They are “a mirror reflecting the broader struggles across creative industries, where financial gains often overshadow the importance of creative integrity and human values.”

Labor disputes yield to easy demonization. But the strikes are compelling Hollywood toward unity on two critical and neglected issues: transparency in a swiftly changing business environment and a defense of human creativity as inimitable and inestimable.

The solution may rest in a renewal of the Bible’s insight that every laborer – whether writer, actor, or producer – is worthy of his or her hire.

Hollywood strikes an opening chord for unity

The union representing screenwriters, and the studios that turn their words into films and television shows, have agreed to restart formal negotiations to end a strike that has stalled the entertainment industry all summer. Those talks were set to begin today.

The dispute has already cost California’s economy $3 billion, according to one estimate. But it has also surfaced qualities of thought that may guide Hollywood through a transition that is about profoundly more than labor contracts.

The strikes are “not merely about better pay, improved working conditions, and regulations on AI use, but rather, a potent call for the recognition of human dignity and artistic integrity,” wrote Wilbur Greene, an Australian editor and literary agent. They are “a mirror reflecting the broader struggles across creative industries, where financial gains often overshadow the importance of creative integrity and human values.”

Throughout the industry’s history, evolutions in technology have brought periodic upheaval. This is one of those moments. Streaming platforms and production studios owned by high-tech companies have disrupted how Hollywood once nurtured writers. Their stable career paths have become uncertain gig work. Artificial intelligence now poses additional challenges.

One consequence is a loss of diverse voices at the very moment society is demanding an ever-widening range of storytelling. Screenwriting is no longer “a job that is accessible for low-income workers, non-white workers, nor workers who grew up far outside metropolitan cities,” noted Ruth Fowler, a seasoned writer and filmmaker, in a recent chronicle of her own struggle to make ends meet. “And yet, these are the voices we so desperately need.”

Labor disputes yield to easy demonization. The pioneer of shorter series and streaming, Netflix, is a ready villain. But a recent conversation among actors, writers, and producers at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University went deeper. The strikes, they agreed, are compelling Hollywood toward unity on two critical and neglected issues: transparency in a swiftly changing business environment and a defense of human creativity as inimitable and inestimable.

“We’re not just charged with educating our students on how to make art, we are charged with educating them on how to make a life in art,” Brandon J. Dirden, a professional actor and associate arts professor of graduate acting, told the Tisch forum. “This conversation, this moment in time, is essential to how they are going to make their lives in art.”

Peter Newman, a producer and head of the MBA/MFA dual degree program in graduate film, agreed. “Students should understand the entire picture, understand what every side is saying, not just one individual point of view,” he said. “This industry is cyclical and resilient. Real talent will always eventually prevail. ... There will be a solution.”

It may perhaps be found in a renewal of the Bible’s insight that every laborer – whether writer, actor, or producer – is worthy of his or her hire.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Eliminating fear from decision-making

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Brian Abbott

Turning to God for inspiration and guidance, we’re better able to move forward with peace and confidence.

Eliminating fear from decision-making

I was on my way to a job interview and feeling a surprising amount of fear. What if I arrived late or dressed wrong? What if I messed up during the interview? What if I were leaving my present employer in a difficult position? I thought about turning around and going home.

I had been praying for God’s guidance and felt that this new opportunity was the result of my prayers. But if that was the case, I wondered, shouldn’t I feel peace and not fear?

These unnerving thoughts swirled through my head, but I continued on to the interview and ultimately got the job – a position that allowed me to put my talents to use in fresh directions and supported my desire to progress spiritually.

While this outcome confirmed for me that God had, in fact, been guiding all my steps, the puzzling questions remained: Why had I felt so much fear on the way to the interview? Isn’t peace in our hearts one of the most certain signs that we have heard God’s guidance and are on the right path?

This was a useful lesson in distinguishing between spiritual sense and material sense – between the understanding that comes from knowing God as ever-present good and the assumptions and beliefs that come from taking in a limited, ground-level view of the world around us. Mary Baker Eddy writes in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Material sense does not unfold the facts of existence; but spiritual sense lifts human consciousness into eternal Truth” (p. 95).

It’s natural for me to turn to God, divine Truth, for guidance when I need to make a decision. God is our creator, our Father and Mother, and always cares for each of us. We are made in God’s own image, as we read in the Bible. These facts link us forever to God and to His laws of good, which are in operation at every moment, weaving God’s spiritual creation into a tapestry of usefulness, goodness, and joy.

Because we are inseparable from God, we always have the ability to express all of His qualities, such as humility, intelligence, and spiritual intuition. These are qualities of spiritual sense, and as we exercise them, we can feel God directing our steps. Whether it comes as a clear, strong conviction or a gentle, developing intuition, God’s guidance always brings us peace and certainty.

I came to see that my fear and indecision prior to the job interview were simply the result of taking a material view of the situation. To spiritual sense, peace had always been there, but the matter-based questions and the fear they fanned hid that peace.

Since fear has no basis in God, good, it has no power. Science and Health says, “Fear never stopped being and its action” (p. 151). As God’s image, we have all that we need in order to face down fear and walk right through it, proving it powerless.

As we accept the opportunities God gives us, we may be required to get out of our comfort zones. But God gives us the vision, self-possession, and courage that we need in order to do this.

These ideas helped me recently when I was feeling pain in one knee the night before a volleyball game. The next morning things were not improved, and I considered skipping the game.

But this time, I readily identified the indecision as stemming from fear. Remembering that fear could never stop my true being or right action, I knew I could make a decision based on what I knew of my spiritual identity as God’s image and likeness, always free, strong, and agile. I didn’t need to fear that a physical condition had the power to harm me.

Replacing fear with spiritual sense, I relied only on God’s guidance. It came to me to get dressed for play and go to the game. By the time I arrived, the pain was gone, and I played without difficulty.

Because you and I are truly God’s image and likeness, fear can’t stop the unfoldment of His goodness in our lives or hide from our hearts the courage to act that He gives us. When we refuse to be intimidated by fear and courageously take the steps God is guiding us to take, we can confidently expect to find fear vanquished and new views of God’s goodness coming to light.

Adapted from an article published in the July 24, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

A fire’s aftermath

A look ahead

We’re so glad you joined us today. Come back next week, when correspondent Sarah Matusek will be reporting from Hawaii on the aftermath of the fires there.