- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

India’s media crackdown intensifies

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Just last week in this space, we highlighted the need for press freedom and the plight of one of our friends and colleagues in Kashmir, Fahad Shah, who has been imprisoned in India for more than a year on specious charges. This weekend, we received word that Indian authorities have now shut down the newspaper that Fahad founded and gave his freedom for.

The Monitor is working with other news organizations and press freedom advocates to secure Fahad’s release. Here we include the full statement from The Kashmir Walla as both a declaration of our support and part of our continuing efforts to see justice and basic human decency upheld.

• • •

The Kashmir Walla is an independent news site based in Srinagar that has been covering developments in Jammu and Kashmir without fear or favour for more than 12 years.

For the past 18 months, however, we’ve lived a horrifying nightmare – with the arrest and imprisonment of our founder-editor, Fahad Shah, and the harassment of our reporters and staff, amid an already inhospitable climate for journalism in the region.

On Saturday, August 19, 2023, we woke up to another deadly blow of finding access to our website and social media accounts blocked.

When we contacted our server provider on Saturday morning to ask why thekashmirwalla.com was inaccessible, they informed us that our website has been blocked in India by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology under the IT Act, 2000.

Next, we discovered that our Facebook page – with nearly half a million followers – had been removed. As had our Twitter account, “in response to a legal demand.” In tandem with this move, we have also now been served an eviction notice by the landlord of our office in Srinagar and we are in process of evicting the office.

Fahad Shah, our founder-editor, was arrested in February 2022 over the coverage of a gunfight. It was the beginning of the saga of his revolving door arrests. He went on to be arrested five times within four months. Three FIRs under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and one Public Safety Act have been registered against him.

In April 2022, the State Investigation Agency (SIA) raided our office and Shah’s home in Srinagar for an investigation into an opinion piece published 11 years ago, in 2011. During the raid, most of our gadgets were seized, reporters were interrogated, and all documents were scrutinized. Since then, our interim editor has been summoned and questioned by the SIA multiple times. Shah remains imprisoned in this case in Jammu’s Kot Bhalwal jail – 300 kms away from home.

Sajad Gul, who worked briefly with us as a trainee reporter, remains in a prison in Uttar Pradesh under the Public Safety Act. He was initially arrested in January 2022.

We are not aware of the specifics of why our website has been blocked in India; why our Facebook page has been removed; and why our Twitter account has been withheld. We have not been served any notice nor is there any official order regarding these actions that is in the public domain so far.

This opaque censorship is gut-wrenching. There isn’t a lot left for us to say anymore. Since 2011, The Kashmir Walla has strived to remain an independent, credible, and courageous voice of the region in the face of unimaginable pressure from the authorities while we watched our being ripped apart, bit by bit.

The Kashmir Walla’s story is the tale of the rise and fall of press freedom in the region. Over the past 18 months, we have lost everything but you – our readers. The Kashmir Walla is beyond thankful that we were read avidly for 12 years by millions.

As to what the future holds, we are still processing the ongoing events.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

What Trump’s four indictments reveal about America

Four criminal indictments of Donald Trump – an apparent boost to his candidacy – suggest the United States is at a pivot point.

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

At this point, Watergate looks downright quaint.

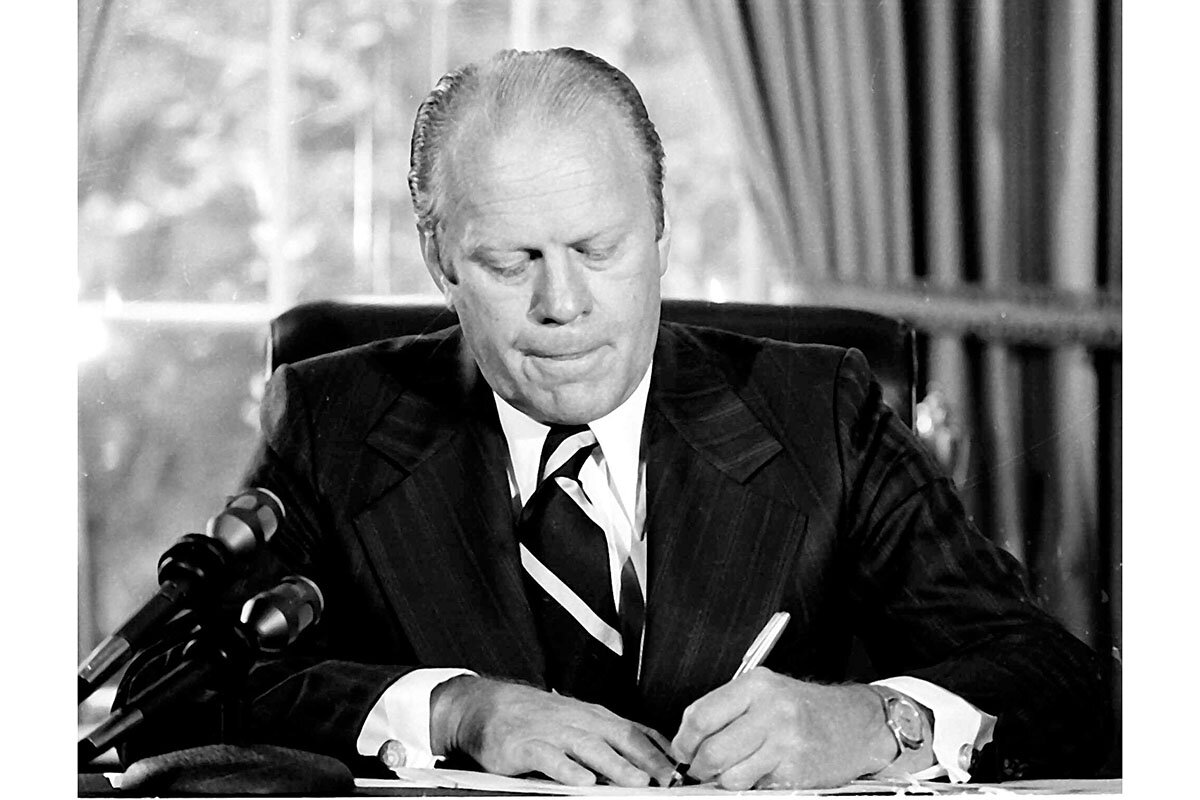

President Richard Nixon was on the verge of impeachment and certain Senate conviction when he resigned, never to run for office again. His successor, President Gerald Ford, pardoned Mr. Nixon in an act of mercy and a bid for national healing.

That was nearly 50 years ago. Today, a former president under fire has a wholly different makeup, and the politics are diametrically opposite: A twice-impeached, four-times criminally indicted Donald Trump is the overwhelming favorite to win the GOP’s presidential nomination next year. And it’s entirely possible he could win the 2024 election. He and President Joe Biden are locked in a statistical dead heat, polls show.

What’s more, Mr. Trump faces felony charges, both federally and in Georgia, that go right to the essence of democracy: alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election results. In that light, presidential historians say, the United States is at a turning point.

The charges could prompt a “resurgence of democratic norms and principles,” says Lindsay Chervinsky, a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. Or we could be seeing the precursor to a presidency unlike any in American history, including Mr. Trump’s first term.

What Trump’s four indictments reveal about America

At this point, Watergate looks downright quaint.

Engulfed by scandal, President Richard Nixon was on the verge of impeachment and certain Senate conviction when he resigned, never to run for office again. His successor, President Gerald Ford, pardoned Mr. Nixon in an act of mercy toward a broken man and a bid for national healing.

That was nearly 50 years ago. Today, a former president under fire has a wholly different makeup, and the politics are diametrically opposite: A twice-impeached, four-times criminally indicted Donald Trump is the overwhelming favorite to win the GOP’s presidential nomination next year. And it’s entirely possible he could win the 2024 election. He and President Joe Biden are locked in a statistical dead heat, polls show.

What’s more, Mr. Trump faces felony charges, both federally and in Georgia, that go right to the essence of democracy: alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election results. In that light, presidential historians say, the United States is at a turning point, with two possible outcomes.

The charges could prompt a “resurgence of democratic norms and principles,” says Lindsay Chervinsky, a senior fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University.

Or we could be seeing the precursor to a presidency unlike any in American history, including Mr. Trump’s first term. If he does return to office, Dr. Chervinsky says, “he’s made it very clear that he will go after his political enemies and he will not be held accountable in any way by our democratic institutions.”

The idea of a second Trump administration, for now, remains a big “if.” It’s still early in the 2024 presidential cycle, and many voters haven’t fully tuned in – even including the fact that the first GOP debate is taking place Wednesday. Mr. Trump has said he will not participate. In addition, the timeline for his criminal cases remains fluid. Though two trial dates have been set for next year – one in March, another in May – it’s possible that pretrial motions could delay all four cases until after the election.

Add to the mix, too, the Justice Department’s appointment of a special counsel for Hunter Biden, the president’s son, over tax and gun charges. Questions persist over whether President Biden had knowledge of or benefited from his son’s business dealings. The president has denied the allegations. But a House GOP investigation has kept the issue in the news, deflecting some attention from Mr. Trump’s legal woes.

Still, the Biden administration – via Justice Department special counsel Jack Smith – and the Georgia and Manhattan prosecutors have set a significant precedent with their indictments of the former president.

“In the same way Ford set one in ’74, this sets a very different one,” says Julian Zelizer, a presidential historian at Princeton University.

In particular, “the cumulative effect of all four, even the state and local indictments, will set a precedent that if you abuse your power, if you’re seen as going beyond what’s permissible, the law will come after you even after you’re president,” Dr. Zelizer says.

Mr. Trump’s criminal indictments are: a Manhattan case over alleged hush payments to a porn star; a federal case over retention of classified documents; a federal case over alleged efforts to overturn the 2020 election; and a Georgia case over an alleged conspiracy to overturn that state’s 2020 election result.

In all, Mr. Trump faces 91 charges, the potential for financial ruin, and the possibility that he goes to prison for the rest of his life. Mr. Trump is widely seen as wanting to regain the presidency in part so he can pardon himself if convicted – though that would not be possible in nonfederal cases, in Georgia and Manhattan.

To many in the GOP primary electorate, most crucially Republicans who may have been inclined to back a fresh face in 2024, a sense of “piling on” appears to have engendered sympathy. Polls show Mr. Trump’s dominance of the GOP field picking up steam beginning in March, right as his first criminal indictment was about to land.

But Mr. Trump’s resilience as a force in American politics goes well beyond renewed cries of “witch hunt.” It goes back to his debut as a presidential candidate in 2015, when he railed against Mexicans “bringing crime” into the U.S. and American jobs leaving the country.

At the time, many political observers thought Mr. Trump would flame out, but in fact, he was remaking the Republican Party before our very eyes, with his performative skills and message of conservative populism.

Just 2 ½ years prior, the GOP ticket was led by avatars of old-style Republicanism, dominated by fiscally conservative elites: former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney and Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin.

Suddenly, the watchwords were “America First” and “build the wall,” and working-class white voters switched parties in droves. Today, many of those same voters are among Mr. Trump’s most avid supporters.

“His appeal never surprised me,” says Henry Olsen, a senior fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center and not a Trump fan. “He was the person who actually was listening or somehow intuited what this segment of voters cared about.”

Politics is a market, Mr. Olsen says. “Eventually somebody figures out that there’s an underserved constituency, and they serve it – and that changes things.”

From former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro to Hungarian President Viktor Orbán and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, right-wing populism is a global phenomenon, and Mr. Trump fits right in.

But right-wing populism, in and of itself, doesn’t present a threat to American democracy, he says. It’s in the criminalization of political opposition – and the demise of the idea of a “loyal opposition.”

“If you cannot see the opposition as loyal,” Mr. Olsen says, “then logic drives you to suppress the opposition in ways that mean they can’t win. That’s the threat to American democracy.”

Biden’s ‘historic’ Asia summit confronts an old foe: History

A summit between the United States, Japan, and South Korea sought to institutionalize the trilateral relationship. But the relations must overcome several sources of distrust: in Asia of U.S. staying power, in China toward the three allies, and in South Korea of Japan.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

U.S. President Joe Biden’s summit Friday with the leaders of Japan and South Korea could set the stage for a more secure and free Pacific region while revitalizing America’s Asia presence. But the question will be whether the summit – hailed by the White House as a “historic first” intending to “institutionalize” relations among the three countries – can fulfill its promise.

If “the spirit and letter of this summit live on ... post-Biden, then this really is historic – for Asia, but also in solidifying that the U.S. continues to be a broker of peace and international cooperation in the world,” says Shihoko Goto at the Wilson Center in Washington.

But are Koreans, and the Japanese, ready to turn away from the past and focus on the future?

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, who has agreed to drop a number of reparations demands related to forced labor during the Japanese occupation, is credited by U.S. officials with rekindling efforts at entente with Japan since taking office.

The Yoon Japan policy “is a very top-down approach to diplomatic relations, but what is less certain is whether, at the grassroots level, there is also movement forward,” says Ms. Goto. “These sensitive wartime grievances may have been shelved, but they haven’t been solved.”

Biden’s ‘historic’ Asia summit confronts an old foe: History

President Joe Biden’s trilateral summit held at Camp David Friday with the leaders of Japan and South Korea could set the stage for a more secure and free Pacific region, while revitalizing America’s Asia presence at a time when many have concluded it is waning.

Indeed, “The Camp David Summit” has the potential to become shorthand for a watershed moment for East Asian security and diplomatic relations, some U.S. officials and regional experts say, in a way similar to how “Camp David Accords” captured a key moment of progress in Middle East peace.

But the question going forward will be whether the one-day summit – hailed by the White House as a “historic first” intending to “institutionalize” deepening relations among the three countries – can live up to its promise.

“The word that’s been bandied about by the Biden administration and others is ‘historic,’ that this was the first time President Biden was hosting foreign leaders at Camp David, that this was a pivotal moment in assuring that [Japan and South Korea] will continue to be much more forward-looking together,” says Shihoko Goto, director for geoeconomics and Indo-Pacific enterprise at the Wilson Center in Washington.

“The big test will be if, no matter what election results we have in coming years, the spirit and letter of this summit live on. If this survives post-Biden,” she adds, “then this really is historic – for Asia, but also in solidifying that the U.S. continues to be a broker of peace and international cooperation in the world.”

If one is to assess the question of the summit’s promise simply by the concrete steps agreed to by Mr. Biden, Japanese Prime Minister Kishida Fumio, and South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol, the answer might seem to be a slam-dunk “Yes.”

The three leaders committed to holding such three-way summits at least once a year. They agreed to hold more joint military exercises around the Korean Peninsula, and to create a hotline to warn one another of sudden security threats, such as North Korean missile launches.

But another plausible answer is more circumspect.

That’s in part because of concerns that a future U.S. president might not be as dogged in supporting and nurturing America’s alliances as Mr. Biden, as Ms. Goto suggests. Many U.S. allies – including in Asia – remain spooked by former President Donald Trump’s disdain for alliances and by the prospect of a return of that perspective to the White House.

But an equal cause for doubts about the trilateral arrangement’s success stem from concerns about the durability of recently blossoming high-level relations between Japan and South Korea.

Despite fits and starts over recent decades at improving relations between Japan and South Korea, the painful history they share – Imperial Japan occupied Korea from 1910 to the end of World War II – has kept resentment of Japan alive in Korea and repeatedly quashed its political leaders’ efforts at rapprochement.

Just two years ago, Japanese and South Korean diplomats refused to take part in a joint press conference at the State Department.

President Yoon is credited by U.S. officials – all the way up to the president – with rekindling efforts at entente with Japan since taking office in May 2022. The Korean leader has gone farther than recent predecessors, agreeing to attend in March the first bilateral summit with Japan in 12 years, and to drop a number of reparations demands related to forced labor during the Japanese occupation.

And now he has embraced the Camp David summit and its objective of building a durable framework for trilateral relations.

Analysts took it as a good sign that President Yoon chose a speech in Seoul last week marking the 78th anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule in 1945 to highlight the Camp David summit and a future of closer ties to Japan.

He said the summit would “set a new milestone in trilateral cooperation contributing to peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula and in the Indo-Pacific region.”

Prime Minister Kishida also offered soothing words in the lead-up to the summit, saying his country has taken “the lessons of history deeply into our hearts” even as it solidifies its partnerships to deter any adversary threatening to “repeat the devastation of war.”

But are Koreans, and the Japanese, ready to follow their leaders in turning away from the past and focusing on the future?

Perhaps tellingly, Mr. Yoon faced immediate blowback from various sectors of Korean society over his choice of venue for hailing the Camp David summit and its promise of closer trilateral ties – and thus with Japan.

The rapprochement with Japan is generally well-viewed among elites in South Korea, experts note, but less certain is how ready the general public is to move on from the past.

The Yoon Japan policy “is a very top-down approach to diplomatic relations, but what is less certain is whether, at the grassroots level, there is also movement forward on some of these very emotional historical issues,” says Ms. Goto.

“These sensitive wartime grievances may have been shelved, but they haven’t been solved,” she adds, “so it seems the topic will remain a big challenge in any post-Yoon administration.”

The other critical factor in trilateral relations going forward will be China.

China was not even mentioned in the summit’s statement. But that was by design to ease concerns, primarily for the Koreans, that the Camp David initiative not be seen as directed at China – which is the top trading partner for both South Korea and Japan.

Beijing has been vocal in its opposition to tighter relations among the three Camp David partners, insisting they aim to create a “mini-NATO.”

Biden administration officials have insisted that the security framework agreed to by the three countries does not aim to become an alliance on the order of NATO – the security accords the U.S. has bilaterally with each Asian ally are stronger than what the three committed to together, for example. Rather, they say, the Camp David “principles” are about enhancing the expanding economic and military security arrangements the U.S. is pursuing across the Indo-Pacific.

Still, an unconvinced China might only be encouraged to take its own steps to counter the U.S., some analysts say, leading to a buildup of opposing security alliances.

“Whatever the U.S. intent, Beijing will regard Biden’s effort as involving the creation of an East Asian NATO [and] that in turn raises the question of whether Beijing will be deterred or provoked,” says Rajan Menon, director of grand strategy at Defense Priorities, a realist foreign policy think tank in Washington.

One outcome Washington might end up with, he adds, is that “China might increase its military ties with Russia and North Korea.”

How China responds to the Camp David summit concerns all three summit participants, others note, but it remains of particular concern to the two Asian members of the threesome.

“Is China just going to pursue its own military buildup, or will it respond to the security cooperation this summit promises by coming up with a similar diplomatic framework to counter the U.S.?” asks Ms. Goto.

“I wouldn’t say concerns about that put the light of day between the U.S. and the other two when it comes to China, but I do think Washington has to keep in mind the geography,” she adds. “For Japan and South Korea, China is right there. For the U.S., it’s not so close.”

‘Hope won’ Guatemalan presidential vote, hurdles remain

Guatemala’s presidential election was defined by official interference. With an anti-corruption candidate’s win, celebrations are tempered by uncertainty over what hurdles to democracy could emerge next.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Sandra Cuffe Contributor

Anti-corruption candidate Bernardo Arévalo – barely on the electoral radar just a few months ago – was chosen as Guatemala’s next president last night, winning 58% of the vote.

There are high expectations from the voters who backed him. They expressed a desire for change from the years of systemic corruption and weakening of institutional independence that have come to define modern Guatemalan politics. His presidential plans include proposals to combat corruption, improve access to public education and health, and foment equitable economic growth.

But analysts say the victor’s first challenges will be the certification of the runoff results and getting sworn into office in January. Mr. Arévalo is expected to face fierce political and judicial backlash in the weeks and months ahead. Losing candidate Sandra Torres has yet to concede.

But, regardless of the challenges ahead, his victory “is a turning point for Guatemalan democracy,” says Gabriela Carrera, a political science professor at the Rafael Landívar University in Guatemala City. What has become obvious, she adds, is that “what is feared” by those currently in power “is the will of the Guatemalan people” seeking change.

‘Hope won’ Guatemalan presidential vote, hurdles remain

Firecrackers, noisemakers, and cheers pierced the night sky Sunday as Guatemalans descended on plazas across the country to celebrate the resounding victory of Bernardo Arévalo, a sociologist and member of Congress seen as a threat to the political establishment.

“Hope won,” José López, a retail worker, says excitedly while on his way to one of the impromptu celebrations in Guatemala City. “People are tired of all the corruption. We are fed up,” he says.

Mr. Arévalo, the Movimiento Semilla party’s presidential contender, garnered 58% of the vote. His rival, former first lady Sandra Torres, obtained 37.2%, but she has yet to concede as her Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza party questions the election proceedings.

Just a few months ago, most in Guatemala knew little about Mr. Arévalo, aside from his famous last name. (His father was the country’s first democratically elected president, ushering in a decadelong “democratic spring” in 1945.) But three candidates, including two popular outsiders, were disqualified from the first-round election on questionable grounds, paving the way for Mr. Arévalo’s surprise second-place victory back in June. Brazen judicial moves targeting his party only galvanized voters further, observers say.

There are high expectations from the voters who backed him. They expressed a desire for change from the years of systemic corruption and weakening of institutional independence that have come to define modern politics here. His presidential plans include proposals to combat corruption, improve access to public education and health care, and foment equitable economic growth.

But analysts say Mr. Arévalo’s first challenges will be the certification of the runoff results and getting sworn into office in January. He is expected to face fierce political and judicial backlash in the weeks and months ahead; many here say threats to Guatemala’s democracy are far from over.

“This is a turning point for Guatemalan democracy,” says Gabriela Carrera, a political science professor at the Rafael Landívar University in Guatemala City. In the coming weeks and months, “the defense of democracy by Guatemalan society, both organized and unorganized,” will play a critical role in ensuring the public’s choice at the ballot box is respected.

A done deal?

Mr. Arévalo’s unexpected success in the first round of voting in June spurred swift backlash from other parties and the public prosecutor’s office. Legal challenges and criminal investigations into how his party was officially registered five years ago were widely considered to be politically motivated. Both Movimiento Semilla and the electoral tribunal, which certified the results of the first-round vote bringing Mr. Arévalo to the runoff, were targeted with raids and arrest warrants this summer.

More interference is likely around the corner. Three days before the runoff, special anti-impunity prosecutor Rafael Curruchiche spoke about several election-related cases, including an ongoing investigation into allegedly fraudulent signatures in Movimiento Semilla’s registration as a party. Arrest warrants and other measures in the wake of the runoff should not be discounted, he told reporters.

“The goal of sabotaging the electoral process is still present,” says Renzo Rosal, a Guatemalan political analyst. Some political and economic elites may try to maintain a grip on power, no matter how blatant – or undemocratic – their efforts. “They seek to derail the process, even though it’s after the fact,” says Mr. Rosal.

Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei congratulated Mr. Arévalo on his victory and invited him to a meeting once the runoff results are official. But the certification of the election results will be key, analysts say. Ms. Torres and her party repeatedly questioned the validity of Movimiento Semilla and the election process in the lead-up to the runoff, setting the stage for a refusal to recognize Sunday’s outcome.

Mr. Arévalo acknowledged “ongoing political persecution carried out by institutions, prosecutors, and judges who have been corruptly co-opted” in his victory speech Sunday night. He said details on his future Cabinet will be announced soon.

Naming a Cabinet may have repercussions. “The day people are announced as potential Cabinet members or people who could be in key positions, those names will be put in the crosshairs of the prosecutor’s office,” says Mr. Rosal.

Seeking change

Voters trickled in and out of a polling station tucked away in a parking lot underneath Guatemala City’s central plaza almost imperceptibly Sunday afternoon, while the plaza bustled with families and vendors.

“We hope this next government brings about changes,” says Mariela Contreras, a Guatemala City resident, after walking out of the polling station. Successive governments have done nothing to improve life in Guatemala, she says. “They have all failed us.”

Mr. Arévalo and his running mate Karin Herrera, a biologist, are not short on proposals for change. Their 64-page government plan addresses everything from structural causes of chronic childhood malnutrition to cracking down on anti-competitive business practices.

Anti-corruption measures were front and center on the campaign trail. A few of them are at the top of Mr. Arévalo’s list of 24 priorities for his first 100 days in office: identifying and reporting corruption cases, establishing a new code of ethics and transparency for government officials, and ensuring information on all government expenditure – “every cent” – is available to the public.

Access to education and health, including expansion and improvement of coverage, is another cornerstone of his plans. In light of high medication costs, he’s promised to create a state company with a network of public pharmacies.

Mr. Arévalo and Ms. Herrera’s plan mentions Indigenous people – who comprise close to half the country’s population – in relation to inclusion and equitable social spending. Like most other party platforms in the country, though, it does not address historical racism, says Victoria Tubin, a sociologist who is of the Maya Kaqchikel people.

Some traditional governance authorities and Indigenous women’s organizations have expressed interest in dialogue with the party during the transition period, says Ms. Tubin.

Job training and creation programs, significant investment in road and highway infrastructure, and the addition of 12,000 officers to the national police force are just a few more points in Movimiento Semilla’s wide-ranging plan.

The feasibility of it all is based, in part, on a projected annual increase in tax revenues without raising tax rates, says Lourdes Molina, a senior economist at the Central American Institute for Fiscal Studies. Instead, the party plans to improve the tax administration system, reduce evasion, and go after customs fraud. While income inequality in Guatemala is among the highest in Latin America, its tax burden is among the lowest and consumers bear the brunt of it. The country loses an estimated $1 billion in revenue annually due to evasion of the value-added tax alone.

“The availability of resources is what determines whether government plans will just end up being campaign promises or whether they will become realities,” says Ms. Molina.

Challenges ahead

Mr. Arévalo’s administration will find few allies in other branches of government. Top courts are stacked against anti-corruption crusaders like him, and Consuelo Porras, the country’s controversial attorney general, is in office until 2026.

In Congress, Movimiento Semilla will hold 23 of 160 seats next year. The current ruling party, Vamos, and the Unidad Nacional de la Esperanza party both won more seats and have formed an informal alliance with several other parties in recent years.

What “we have been calling the ruling alliance is going to continue and will even become stronger,” says Mr. Rosal, the political analyst. “We’re easily talking about at least 110 or 120 congressional representatives, so it is an extremely strong majority that will dominate Congress, its executive committee, and key commissions,” he says.

Should Movimiento Semilla lose its status as a registered party, its elected lawmakers would take office as independents. They would be barred from presiding over congressional commissions, among other roles. A judge ordered its status be revoked in July, but the electoral tribunal refused to comply given it is illegal to cancel a party while an electoral process is underway. The country’s top court agreed, putting those efforts on hold until October.

“The other important thing is that it would bog down Semilla leadership in legal struggles,” says Ms. Carrera, the political scientist. “The party’s most important leaders at the moment are elected congressional representatives,” she says.

For now, officials cannot suspend the party, but that doesn’t mean they won’t pursue other measures in the meantime. “There is a series of dynamics that we are unable to see but that is even more dangerous,” says Ms. Carrera.

“Definitely what is feared” by those currently in power, she adds, “is the will of the Guatemalan people.”

The not-so-glamorous Instagram life of a US senator

At a time when many bemoan the use of social media to exploit divisions and further polarize America, independent Sen. Angus King of Maine is striving to do the opposite.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

He eats microwave meals, weed-whacks his neighborhood’s overgrown grass, rides a Harley and the Washington Metro – and earlier this year traveled to the Ukrainian capital to meet President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Welcome to the glamorous life of a United States senator, courtesy of Angus King’s Instagram feed.

The Maine senator may not be the king of Instagram – he has just 32,400 followers, compared with, say, the 8.5 million of New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. His down-to-earth approach is more the speed of Maine lobstermen trolling for crustaceans than politicos scrolling for scuttlebutt. But in a way that resonates with many along the craggy coasts of Maine, his understated commentary on Washington and the people he represents challenges the pervasive cynicism about politicians.

He defies the downward pull of the social media vortex, pulling back the curtain on the humanity of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle – Virginia Democrat Sen. Tim Kaine playing the harmonica and Mississippi Republican Sen. Roger Wicker singing – while also being frank about their disagreements.

Not everyone is a fan; some people use the comments space to rail against his voting record. But others are grateful, as one who wrote simply: “Thank you for bringing sanity to Washington.”

The not-so-glamorous Instagram life of a US senator

He eats microwave meals, weed-whacks his neighborhood’s overgrown grass, rides a Harley and the Washington Metro – and earlier this year traveled to the Ukrainian capital to meet President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Welcome to the glamorous life of a United States senator, courtesy of Angus King’s Instagram feed.

“Here’s one of [Democratic Sen.] Tammy Duckworth looking out the back of a helicopter in Baghdad,” he says, scrolling through his account after a Monitor reporter asked him about it. I’ve got a new hero, he wrote after watching the former Black Hawk helicopter pilot circle the place where she had been shot down 15 years earlier, losing both legs.

“There I am raking leaves,” says the Maine independent, adding that it’s important for people to realize that senators do yardwork and use airports.

Wait, what – no private jet?

Far from it.

“One of the funniest ones was when my plane got grounded in Washington,” he says, coming across a June 2019 post when he banded together with two software engineers, a college professor, and a lawyer he’d never met to make the trip back home. “We rented a car and drove overnight,” he says. That post prompted one of his biggest responses ever, he says.

The Maine senator may not be the king of Instagram – he has just 32,400 followers, compared with, say, the 8.5 million of New York Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. His down-to-earth approach is more the speed of Maine lobstermen trolling for crustaceans than politicos scrolling for scuttlebutt. But in a way that resonates with many amid the craggy coasts and whispering pines of Maine, his understated commentary on Washington and the people he represents challenges the pervasive cynicism about politicians and their polarizing use of platforms from Twitter to TikTok.

“You would almost look at it and think it’s not even a politician’s social media account. It could just be someone who visits D.C. often,” says Andrew Selepak, a social media professor at the University of Florida. “But I think that’s probably a bit reflective of him as a politician.”

In an industry often associated with big egos and a myopic focus on one’s own interests, Senator King shows an aptitude for thoughtful observation. He takes an almost childlike delight in discovering a view of the Washington Monument through a crack in the elevator doors, thanks to a window in the Senate elevator shaft that he never noticed. He revels in sunsets or a Maine back road lined by snow-dusted evergreens that provide a respite from politics.

And he defies the downward pull of the social media vortex, pulling back the curtain on the humanity of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle – here’s Virginia Democrat Sen. Tim Kaine playing the harmonica and Mississippi Republican Roger Wicker singing “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing” – while also being frank about their disagreements.

Not everyone is a fan; when he posted a dawn photo taken from the Capitol after a 25-hour nonstop session to pass the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan in March 2021, one commenter wrote, “WHY DID YOU VOTE AGAINST RAISING THE MINIMUM WAGE HOW OUT OF TOUCH ARE YOU.” The senator pointed him to a statement on his website. Hope it helps explain, he added.

Indeed, beyond the rainbows and kittens, there is often a substantive and sober tone – whether he’s warning about climate change or musing about the health of our democratic institutions.

Early in his career, he worked as a staffer on the Hill in the 1970s, when senators lived in town with their families and got to know each other. Now most leave on Thursday afternoons and don’t come back until late Monday. Apart from the bipartisan Senate prayer breakfast, there are hardly ever any opportunities to just get to know each other, explains the former Democrat who switched to independent when he ran for governor in 1994, but still caucuses with the Democratic Party in Congress. So he started hosting impromptu dinners, picking up ribs, beans, and coleslaw and inviting a few fellow senators – some Democrats, some Republicans – over to his 908-square-foot home in Washington.

“You can almost see the wheels turning and see the person say, ‘Oh, this person isn’t the monster I thought they were,’” says Senator King in a hallway interview in May, a few weeks after holding his first post-pandemic dinner.

But he runs out of time looking for the post he really wanted to share – a photo of dirty dishes after one such gathering before the pandemic. It was his creative way of capturing the moment without infringing on the privacy necessary to foster bipartisan ties.

Here it is, further down in his feed, April 23, 2018: a takeout container with a couple of ribs sitting atop aluminum foil, a nearly empty jar of sauce, and dirty plates crammed onto a small counter.

What you see here is the remains of tonight’s edition of my personal project to make a dent in this unfortunate reality, he wrote, explaining how the lack of trust makes it hard to reach the compromises necessary to get things done.

“Beautiful dishes, sad truth,” commented one follower.

Another took a more hopeful view: “Thank you for bringing sanity to Washington.”

Points of Progress

Sharing knowledge, from Guatemalan farms to maps of illegal fishing

Our progress roundup shows an exponential benefit to sharing expertise and knowledge. In Guatemala, farmers go to school to learn from each other. And a new open-source mapping project lets people around the world help look for suspicious patterns from fishing vessels.

Sharing knowledge, from Guatemalan farms to maps of illegal fishing

1. United States

The United States finished destroying its chemical arsenal July 7, marking the first time declared weapons of mass destruction have been eliminated globally.

Modern chemical weapons were first used during World War I, after which they were widely condemned as inhumane. In 1925, the Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of chemical weapons, and in 1997, a United Nations convention required their eradication. Chemical weapons remain in use by some terrorist groups, and some nations have been accused of retaining them illegally.

The U.S. amassed huge volumes of chemical weapons for decades as a deterrent and began dismantling its stockpile in 1990. But the endeavor has taken far longer – and cost much more – than originally anticipated, because of safety concerns for workers and communities where the processing facilities are located.

“Most people today don’t have a clue that this all happened – they never had to worry about it,” said Irene Kornelly, chair of a citizens advisory commission in Colorado that has assisted with the program. “And I think that’s just as well.”

Sources: The New York Times, The Guardian

2. Guatemala

Guatemalan agroecology schools are facilitating the spread of Indigenous knowledge to strengthen smallholder farmers. As monocultures such as palm oil were encroaching on communities, the Utz Che’ Community Forestry Association in 2006 started the first of some 40 programs across the country. Groups of 30 to 35 participants identify what strategies they want to pursue, from bokashi fertilizing to making natural pesticides, and then learn campesino a campesino (farmer to farmer) on their own lands. Former enrollees provide expertise and guidance, mirroring traditional methods of passing knowledge down through generations. Utz Che’ estimates that it has improved the livelihoods of 33,000 families, which protect 74,000 hectares (182,858 acres) of forest.

“The recovery and, I would add, revalorization of ancestral practices is essential to diversify fields and diets and to enhance planetary health,” said Claudia Irene Calderón of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Practices that are rooted in communality and that foster solidarity and mutual aid [are] instrumental to strengthen the social fabric of Indigenous and small-scale farmers in Guatemala.”

Source: Mongabay

3. Netherlands

The Netherlands is returning nearly 500 artifacts taken from Indonesia and Sri Lanka during colonial times. The country’s first-ever repatriation of objects followed a 2020 Dutch advisory committee recommendation that objects acquired through colonial conquest be returned. In July, King Willem-Alexander apologized for the country’s role in the slave trade.

Last year, Indonesia requested from the Netherlands a list of objects that included the Lombok treasure, looted in 1894 from a royal palace, and 132 pieces of modern art from Bali. Not included in the restitution were the remains of Java man, an ancient human fossil. The advisory committee made a distinction between cultural heritage objects that were looted and those, such as Java man, that were not removed under duress.

“Nothing has been declined, but some things take longer than others,” said a Dutch spokesperson. The government said the advisory committee continues to evaluate requests for returns.

Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum will return the 6-foot ceremonial Cannon of Kandy and five other decorated weapons to Sri Lanka later this year.

Sources: The Guardian, Museums Association

4. Nigeria

Flood-tolerant varieties of rice are increasing productivity for 30,000 farmers in Nigeria. The Africa Rice Center and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), whose researchers won an agritech prize in May, say the new strains of rice produce higher yields and can survive more than two weeks of submergence – double what older rice types commonly planted in Africa can tolerate.

Many countries in Africa have faced increasingly catastrophic deluges in recent years, due in large part to climate change. Flooding in West Africa last year killed 800 people and in 2020 destroyed 25% of Nigeria’s rice harvest.

Gene technology remains controversial among some governments and consumers with concerns about environmental impacts and human health, but genetically modified, flood-resistant “scuba rice” has proved useful in flood-prone Asia since 2009.

“With improved flood-tolerant rice varieties, smallholder farmers in the region are able to adapt better to the floods that used to destroy their crops, ensuring farmers’ yields and income,” said IRRI scientist Venuprasad Ramaiah. The institute estimates that more than 90% of Africa’s potential rice-growing land remains untapped.

Sources: SciDev.Net, International Rice Research Institute

World

Open-access ocean maps created by a nonprofit, Global Fishing Watch, are tracking the global fishing fleet to help prevent illegal fishing. A primary driver of overfishing, illegal fishing threatens marine ecosystems, food security, and the human rights of fishing crews.

Global Fishing Watch started as a collaboration among several tech companies in 2015. It uses location data that fishing vessels are required to broadcast, along with machine learning and satellite information, to create publicly available, easy-to-read maps. Law enforcement can more easily pursue illegal fishers in a wilderness that, due to its size, is otherwise difficult to police.

The effort has seen success, even among “dark vessels,” which disable their transponders to go undetected. Illegal fishing off the coast of North Korea decreased by 75% after the organization uncovered widespread plunder of squid in 2017-18.

In the marketplace, “buyers and suppliers want to try and prove their due-diligence,” said Tony Long, the group’s CEO. “They’re starting to recognize the role transparency has to play. They use this information to hold fleets accountable.”

Sources: Good Good Good, The Washington Post

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

‘Honesty will win’

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The presidential elections that unfolded in Guatemala and Ecuador yesterday each had its own brand of intimidation – political interference in one, violence in the other. Yet in both countries, voters were undeterred. The surprising results they set in motion underscore the effect of individual integrity in neutralizing fear.

“Honesty will win,” said Yaku Pérez, the candidate from the Alianza Claro Que Se Puede (Of Course We Can Alliance), a minor party in Ecuador.

People in Ecuador and Guatemala are looking for solutions to entrenched corruption. According to the opinion survey AmericasBarometer, 65% of people across the region say that more than half of all politicians are corrupt. That frustration helps to explain what voters in Guatemala saw in Bernardo Arévalo, the son of a beloved former president who led an upstart campaign to victory in yesterday’s runoff ballot. Mr. Arévalo is the leader of a young reformist party.

In Ecuador and Guatemala, voters may be charting a way forward. As Mr. Arévalo said, the participation in the election “is an act of defense of democracy and at this moment it meant an act of courage.” Backing integrity over fear marks a first step in recovering the civic spaces of self-government.

‘Honesty will win’

The presidential elections that unfolded in Guatemala and Ecuador yesterday each had its own brand of intimidation – political interference in one, violence in the other. Yet in both countries, voters were undeterred. The surprising results they set in motion underscore the effect of individual integrity in neutralizing fear.

“Honesty will win,” said Yaku Pérez, the candidate from the Alianza Claro Que Se Puede (Of Course We Can Alliance), a minor party in Ecuador. He described the vote as laying “the foundations of the new Ecuador.”

As in many countries in Latin America in recent years, people in Ecuador and Guatemala are looking for solutions to entrenched corruption and the criminal activities of gangs and drug cartels. According to the opinion survey AmericasBarometer, 65% of people across the region say that more than half of all politicians are corrupt.

That frustration helps to explain what voters in Guatemala saw in Bernardo Arévalo, the son of a beloved former president who led an upstart campaign to victory in yesterday’s runoff ballot. Mr. Arévalo is the leader of a young reformist party. He pledged to reverse what one political analyst described as the systematic dismantling of public institutions under outgoing President Alejandro Giammattei.

“I want a new Guatemala,” Victorina Hernández, a teacher, told The Wall Street Journal after voting. “I want a lot of changes. No corruption, better education, health and society. No more hungry children.” During a campaign in which state prosecutors disqualified more prominent anti-corruption candidates, Mr. Arévalo has said his first priority would be to restore judicial independence.

Corruption also overshadows Ecuador, where President Guillermo Lasso called an early election to avoid a potential impeachment trial over graft allegations and has vowed to resign. But the election there was marred by violence, including the assassination of a mayor and an anti-corruption presidential candidate who promised to take on drug cartels. At least two candidates wore bulletproof vests to cast their ballots.

Despite that atmosphere of fear, however, the election showed the power of public appeals for honest government. Like their counterparts in Guatemala, enough voters in Ecuador backed a young reformist candidate, Daniel Noboa, to force a runoff in October.

For Latin Americans to break from the “vicious cycle” of corruption, wrote former Costa Rican Vice President Kevin Casas-Zamora in The New York Times, they “need to build institutions such as robust political parties, independent judiciaries, impartial electoral authorities and strong legal protections for press freedom and civic activism.”

In Ecuador and Guatemala, voters may be charting a way forward. As Mr. Arévalo said last night, the participation in the election “is an act of defense of democracy and at this moment it meant an act of courage.” Backing integrity over fear marks a first step in recovering the civic spaces of self-government.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Prayer for the outcast

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Cheryl Ranson

Through Christly affection and heartfelt prayer, we can perceive our unity with one other as God’s loved offspring.

Prayer for the outcast

I still remember the little girl in my first-grade class who often sucked her thumb. And I can vividly picture my mocking classmates calling her a baby and making her cry. Most of all I recall how helpless I felt, understanding that something was wrong but having no idea what to do.

It’s easy to excuse a six-year-old for failing to confront this group behavior. Since then, I’ve learned that onlookers can speak up – that bullying and ostracism should be condemned. Yet Christian Science has shown me it’s possible to go further, to bring healing to social interactions.

For most of us, society represents a mix of motives and hopes, opinions and fears. Even on a micro level, it can seem beyond individual control.

Viewed spiritually, though, consciousness is the dwelling place of God’s kingdom. Christ Jesus brought this fact to light when he said, “The kingdom of God is within you” (Luke 17:21).

That God’s nature – His goodness, grace, and peace – is expressed in us is more than an interesting or even comforting truth. Seen in the light of God’s omnipresence, this divine fact challenges the supposition that mortal existence is real and substantial. As Spirit, God defines His creation spiritually, eternally supplying every good quality. As Principle, God establishes and governs all activity as purposeful, beneficial, and unerring. As Love, God tenderly blesses and comforts each of His ideas, without exception.

These verities are game-changers. In the midst of unkindness, bullying, injustice, or violence, God is present to heal. If this seems implausible, consider Jesus’ example. Petitioned by lepers, the principal outcasts of ancient times, he cured them. Accosted by a demon-possessed pariah, he effected a complete physical and societal transformation. Cultural and social convention fell before this Christly love.

Transformation of collective behavior necessarily begins with individual thought. Christian healer Mary Baker Eddy shows deep reflection to be basic to prayer: “Watch, and pray daily that evil suggestions, in whatever guise, take no root in your thought nor bear fruit. Ofttimes examine yourselves, and see if there be found anywhere a deterrent of Truth and Love, and ‘hold fast that which is good’” (“The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany,” p. 128).

When we prayerfully turn from a mortal view of ourselves and long to discern something of God’s creation, our perspective shifts. Infinite Love enables us to accept and defend not only our own God-given nature but that of every one of God’s children. We start to see one another as fellow members of a “holy household.”

One summer I was hired to lead a dozen teens to homestays in another country. Part of their preparation involved team-building strategies and group exercises. But at the first meeting, one of the 12 was so ill at ease that he physically distanced himself from everyone else and refused to communicate. Despite my and his peers’ encouragement, he wasn’t able to participate.

I knew that prayer was the only sure answer to the boy’s need to feel at home. That night I reached out to God in wholehearted prayer, with no agenda but to hear His guidance and feel His love. Soon I was filled with a deep conviction of Love’s ever-presence. All concern about the situation with the teen dropped away as I relaxed into the comfort and assurance of that spiritual affection.

The following day brought a dramatic change. Our “outcast” suddenly joined the group and started joking with the other students. Within a couple of hours he was entirely integrated into our activities. And a few weeks afterward, he was able to help a friend who was going through a mental health crisis.

What was it that turned the troubling circumstances around? To me, it was the glimpse I’d gained of God’s goodness and love as discernible and demonstrable in our daily lives. Jesus illustrated this certainty throughout his ministry, preeminently embodying Christ, “the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness” (Mary Baker Eddy, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 332).

Whenever we listen intently for God’s comfort and direction, Christ makes them clear to us right where we are. Christ decisively destroys whatever is unlike God – including distressing actions and reactions. A heartfelt commitment to embracing spiritual reality will bring healing. No one exists outside the circle of infinite Love.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, July 6, 2023.

Viewfinder

Surfers for Hilary

A look ahead

Thank you for spending part of your Monday with us. Please come back tomorrow when we take a deeper look at the closing of The Kashmir Walla, which was an essential independent voice in Kashmir. What’s next for press freedoms in India?