- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The March on Washington continues

Ken Makin

Ken Makin

Last weekend, the United States celebrated the 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. For me, it was three years ago that I saw the march in a new light. That revelation didn’t appear because of a profound interview or extensive study of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

I saw the March on Washington differently because of rare color photos from the Civil Rights Movement.

It was ironic that those pictures helped me to see the famous march in a newer and fuller way. For years, I had interpreted the event as something far in the past, and largely from the perspective of Dr. King’s famous words. I know better now.

The march isn’t just a story of Dr. King’s legendary advocacy. It is also the story of a legion of civil rights activists – and of us. During the most turbulent of times, a quarter of a million people descended on our nation’s capital and demanded change. The yearslong labor and strategy of women such as Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and many others were essential.

As we commemorate the march, I am reminded of the demands that Dr. King and others made that have gone unmet. He spoke of a “bad check” that America has given Black people, which continues to show up in racial disparities and police brutality.

It is remarkable to see, even in the shadows of violent racism, the conscientiousness of a platform that would uplift all Americans. This is paramount to Black leadership and governance, from the first post-Civil War Reconstruction to the second reconstruction during the 1960s.

Limited rhetoric of the March on Washington does us no favors. We should honor the actions of activists and Americans by finishing the race toward a better country, with the basic accommodations that are essential to living a full and free life.

The march continues.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For this Ukrainian veteran, why Russians fight is still a puzzle

Resilience or stubbornness? In the yearslong conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and in the last 18 months of war, it’s a matter of perspective. We talk to a veteran Ukrainian artillery commander during a brief break from the counteroffensive.

For eight years, the Ukrainian artillery commander with cropped gray hair and angular features has been on the front lines, facing Russians or their local separatist proxies. Throughout that time, he says, he has wondered often about the motivations of those fighting on the other side, and what they seek to gain.

The commander gives the name Oleksandr – call sign Kirik. He says he is busy as one cog in a Ukrainian war machine that is spread across a 600-mile front. But on this hot summer day, on a short break from the war and a Ukrainian counteroffensive that has made only marginal advances, Kirik muses about Ukrainian resilience and Russian stubbornness.

“Of course, Russians are learning from their mistakes,” he says, as artillery duels rumble over the horizon. “I can’t say the Russian army is weak. They have more ammunition and people. But they are losing this war; why do they still go to conscription offices?

“What amazes me a lot in the last one and a half years is that the stupid Russians – they keep coming,” he says. “There are so many body bags and coffins going back to Russia. ... How much more can they keep doing that?”

For this Ukrainian veteran, why Russians fight is still a puzzle

His hair tightly cropped and streaked with gray, and his angular features hardened by years of fighting Russian troops, the veteran Ukrainian artillery commander paused near the front line to reflect.

Ukraine’s counteroffensive had been underway for two months but had so far made only marginal advances against entrenched Russian positions supersaturated with mines.

The officer, who gives the name Oleksandr – call sign Kirik – acknowledges that he only knows his narrow slice of Ukraine’s southeastern front, in the direction of Donetsk, which is sandwiched between the main Ukrainian thrusts on either side of him.

The Monitor first met the artillery commander on a frozen field in February, as his unit pummeled Russian positions daily with a captured 152 mm gun they named Revenge.

This hot summer day, with a nod to the mounting and very public pressures on Ukraine to deliver progress on the battlefield, he notes with a wry, gold-toothed smile that he officially “can’t say anything about the counteroffensive” or risk “going to jail.”

But under a canopy of grapevines in the garden of a village house made available to his unit – while half of the soldiers are delivering ammunition, the other half digging trenches, and all awaiting repair of their new, main gun – Kirik muses about Ukrainian resilience, Russian stubbornness, and this wretched war.

“Of course, Russians are learning from their mistakes. They learned some stuff from us, and from their mistakes,” says Kirik, chain-smoking as artillery duels rumble over the horizon. “Everyone is tired” of improved Russian defenses, “and is doing what they can together,” he says.

“I can’t say the Russian army is weak. They have more ammunition and people,” says Kirik. “But they are losing this war; why do they still go to conscription offices?”

The Russians “keep coming”

The house’s small backyard table is cluttered with a smorgasbord of stuff: a red Porsche cigarette lighter; a three-hook #1 fishing lure with green, yellow, and orange stripes; coffee cups stained with overuse; and mosquito coils to burn at dusk.

For eight years Kirik has been in the military, on the front lines ever since 2015, a year after Russia and local separatist proxies took control of parts of eastern Donetsk and Luhansk regions, and all of the Crimean Peninsula. Cutting Russia’s supply lines to Crimea is a main goal of the Ukrainian counteroffensive.

Throughout that time – and despite working for a few years in Russia before the war – he says he has wondered often about the motivations of those fighting on the other side, and what they seek to gain.

“What amazes me a lot in the last one and a half years is that the stupid Russians – they keep coming,” he says. “There are so many body bags and coffins going back to Russia, and hundreds of bodies are still left in the treeline. ... How much more can they keep doing that?

“Don’t you see the news?” he asks, as if addressing the Russian fighters. “Check the news: Here [in Ukraine] you are retreating.”

He says he is busy, and “working” all the time, as one cog in a Ukrainian war machine that is spread across a 600-mile front to counter invading Russian troops.

Kirik has become a TikTok sensation; to crowdfund donations to the military, he paints artillery shells with bespoke messages before firing them. Now, the fan of Metallica and Nirvana engraves high-caliber machine gun shells with his battalion number, for charity, and collects battle artifacts from the front.

Back in February, snow and ice caked the muddy fields where Kirik’s squad played war games – sometimes against Russian soldiers, who were also gaming online – until they were given target coordinates of enemy positions around Donetsk.

“Why did the ... Russians bring this gun here, so we can kill their own people – and they keep giving us ammo?” Kirik said at the time. By then, his squad had already fired some 3,000 shells, all of them captured, through the howitzer.

“Do you know how many Russians we have killed with their own guns?” he asked.

Zelenskyy vs. Putin

Kirik’s unit has since had a hardware upgrade, but the war grinds on.

He recalls living in Russia a decade ago, and how strong the propaganda was on state-run television, which reported wistfully about the days of the Soviet Union, and about the good work of the Russian government and, of course, of President Vladimir Putin.

“Some time ago, I had a chance to become a citizen of Russia,” says Kirik. “I can’t imagine what I would do now. Fight in the army?

“Even if you live in an information black hole, you can see that [Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskyy is not afraid of anything, and goes everywhere on the front line,” he says.

“Putin has three layers of security at the Kremlin and has not once been on the front. As a Russian citizen, how can you follow these people, these cowards?” asks Kirik. “This [Ukraine] is a country of brave people.” The Russian leader reportedly made a nighttime visit to occupied Mariupol in March and visited the Kherson region in April.

During his obligatory military service decades ago, Kirik says he was with many senior officers from the Crimea and Donetsk regions, and he is sure that he is “fighting a few of them today.”

His separatist friend

Reflecting on how pro-Russian Ukrainians think about separatism, Kirik tells the story of a friend he grew up with, who he says was typical, and whose parents lived in Donetsk city.

The boyhood friend called Kirik in 2014, before Russian troops and a proxy force of local separatists seized control of eastern Ukraine and captured Crimea.

“He said, ‘Join us; let’s fight Ukrainian nationalism. We have camps and get paid $100 a day,’” Kirik recalls his friend telling him. Later in the year, the friend appeared on Ukrainian television, a captured prisoner of war.

“I was surprised how someone could be brainwashed,” says Kirik, adding that he expected the friend to have been released and taken up arms again, on the Russian side. “I am sure he is now dead in the forest.”

When he worked in Russia in 2012 and 2013, Kirik says he encountered examples of separatist attitudes. When asked where people were from, for example, instead of saying “Ukraine,” some would reply, “I am from Crimea” or “Donbas,” both areas with particular historical ties to Russia.

“In every country, there are always people who are patriotic, and others who don’t like the government, who are not happy with anything – even if you put a gold toilet in their room,” says Kirik.

He is shocked when fellow citizens are nostalgic about the former Soviet Union.

“People say it was amazing living in the USSR. Then you ask them, ‘What was good?’” says Kirik. “I remember a lack of food and products, and closed borders.”

Challenge posed by collaborators

Likewise, he is surprised by Ukrainian collaborators with Russia in occupied territories, given the example of deprivation in long-occupied regions, and much of Russia itself.

“What did they expect, when everything is just miserable, and their economy is going down? But still, they wait for the Russians and for Russian world,” says Kirik, referring to a Moscow campaign to consolidate cultural control over occupied Ukrainian territory.

“The propaganda level is very high ... but you can also see how far the quality of your life has dropped,” he says. “I don’t know what is in their minds.”

Still, there is no shortage of pro-Russian Ukrainians in occupied areas, which will complicate Ukraine’s advance.

“It’s always hard to have a fight for territory on which they have a lot of collaborators. In Crimea, they were waiting for years for Russians; it’s harder to fight,” he says.

By contrast, the places where Ukraine last autumn made sweeping gains, by pushing Russian forces out of the northeast Kharkiv region and the southern city of Kherson, were made “easier” because “people were resisting [the occupation] very much,” he says.

“That helped us a lot. Not many people were waiting for the Russians there,” says Kirik. “A lot of people were waiting for the Ukrainians to return.”

Asked if he will next be seen in liberated Crimea, Kirik laughs, then turns serious.

“Of course, to get to Crimea requires a lot of hard work. You have to be realistic,” says Kirik. “We can talk about Crimea only when we are approaching Crimea – and we are not there yet.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

Tracing Lahaina’s story, from royal kingdom to fiery blaze

Lahaina, a historic town and community burned by a wildfire on Maui, has seen upheavals and fresh starts before. Now residents face a new era of renewal following the fire.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

Jack Kiyonaga Special contributor

The story of Lahaina, Hawaii, is one of transformation – from a place of Native royalty to one of missionaries, sugar moguls, and the tourists who fled this month. Transformation also runs through the roots of Lahaina family trees, generations that have loved and lost, left and stayed, worked and worshipped here.

The deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century, with 115 confirmed dead, has transformed this place again. No one knows what fruit the seeds of recovery will bear, but those who love Lahaina intend to plant them.

“I want it to look and stay like the Lahaina town that we know,” says Cindy Williams, a resident born and raised in the town whose home survived the blaze. “The cultural essence and the local history of it, the community helping each other.”

Discussion of the tragedy often involves the legacy of land, which Native Hawaiians hold sacred.

“We start our histories with the landscape,” says Davianna Pomaikai McGregor, retired professor of ethnic studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. The fire represents a hulihia, an overturning, she says.

Tracing Lahaina’s story, from royal kingdom to fiery blaze

From her backyard fence, Cindy Williams takes in the town where she was born and raised. Not even wildfire could make her leave Lahaina.

Etched into the hillside behind her is a large letter L, whitened with lime by students at her alma mater, Lahainaluna High School. Below her is the spindly smokestack of the Pioneer Mill Co., recalling an era that lured her Portuguese grandparents with jobs in sugar cane.

But some landmarks are missing from the scene since an Aug. 8 wildfire, the most destructive of multiple blazes that ignited on Maui, Hawaii, that day. Gone is the Waiola Church, where her husband’s family pastored. Gone are hotels and stores. The fangs of flames devoured houses just a few blocks from her. Sometimes it’s hard for Ms. Williams to look.

The story of Lahaina is one of transformation – from a place of Native royalty to one of missionaries, sugar moguls, and the tourists who fled this month. Transformation also runs through the roots of Lahaina family trees, generations that have loved and lost, left and stayed, worked and worshipped here.

The deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century, with 115 confirmed dead to date, has transformed this place again. No one knows what fruit the seeds of recovery will bear, but those who love Lahaina intend to plant them.

“I want it to look and stay like the Lahaina town that we know,” says Ms. Williams. “The cultural essence and the local history of it, the community helping each other.”

That’s what she’s doing now, transforming her garage into a depot of donations for neighbors. People can come by for noodle packets, canned goods, or a smile.

Sacred land

Discussion of the tragedy often involves the legacy of land, which Native Hawaiians hold sacred.

“We start our histories with the landscape,” says Davianna Pomaikai McGregor, retired professor of ethnic studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “It’s the akua,” or deities, “our natural elements, endowing the land with its features and its resources.”

How Lahaina Looks Forward

What does it take to report on a disaster sensitively, safely, and through a Monitor lens? How can a reporter find credible hope for eventual renewal amid devastation? Writer Sarah Matusek spoke to host Clay Collins about reporting from West Maui immediately following the Aug. 8 fires – and about finding generosity and agency in abundance.

The fire represents a hulihia, an overturning, she says. The professor points to a disturbance in nature that began long ago – the transformation of wetlands into stretches of fallow cash-crop fields today.

It’s a scene far different from what met Maui’s first explorers by canoe. Among the plants they brought were breadfruit, whose groves later graced Lahaina with shade.

Capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Centuries after Polynesians settled the Hawaiian Islands, the district of Lahaina served as the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom during the first half of the 19th century.

A range of factors – including its home to sacred sites, waterways, and access to fisheries – helped secure Lahaina’s status. During that period, the kingdom was recognized as sovereign through a proclamation by Great Britain and France.

Kaipo Kekona wears that Independence Day date – Nov. 28, 1843 – on a baseball cap. It shields him from the sun in spacious Napili Park, north of the Lahaina wreckage.

The Native Hawaiian, among those who don’t consider themselves American, coordinates one of several mutual aid efforts separate from the government. For many residents of the islands, the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom and then annexation still color their perception of the U.S. government.

“We are capable of caring for ourselves,” says Mr. Kekona, directing volunteers in a field.

The landing at Lahaina, today known as the town harbor, offered a gateway for the kingdom’s travel and largely agricultural trade. Inland, Native Hawaiians cultivated fishponds, and an intricate irrigation system called auwai – channels and canals – watered taro patches. The plant with heart-shaped leaves features in the Hawaiian creation story and served as a staple of the Native diet.

Missionaries arrive

Customs began to change over the ensuing decades with new arrivals. New England missionaries started to appear around the 1820s. Their gospel so moved Queen Keopuolani that she founded what would become known as the Waiola Church, just behind the royal seat of the kingdom.

Though razed by the recent fire, the building has a history of resurrection from multiple disasters. An 1894 account of a blaze that year reads: “A Bible, the sacred vessels and a harmonium were saved, but the property was demolished.”

Linda Norrington is “confident” the house of worship will rise again, even if it takes years. The church moderator recalls how, during open-door services, she could hear the songs of birds. One flew in and landed on the altar.

“It felt like you were in God’s presence,” she says.

As perspectives of faith transformed in the 1800s, so did the use of land. Ground held by Native Hawaiian families was increasingly sold, leased, or taken by large-scale producers of sugar cane and pineapple grown for economic profit.

Plantation era

The Pioneer Mill Co., which ran from 1860 to 1999 producing sugar, drew not just immigrants from around the world but greater thirst for water to cultivate crops. One historical report from a Lahaina committee, created to investigate the cause of famine in 1867, largely blamed the expansion of the sugar industry along with the loss of traditional farming and natural-resources stewardship.

“God is not the reason for this lack, nor is it because there is a lack of rain – instead it is the lack of thought by men,” reads a translated section, from Hawaiian to English, by ethnographer Kepa Maly. The last of Maui’s plantations, which helped grow the island’s economy, closed in 2016 due to labor and transportation costs.

Land use is much discussed as context of the Aug. 8 Lahaina fire, whose cause remains under investigation. The county of Maui, meanwhile, has sued Hawaiian Electric, alleging that the utility was negligent in failing to shut off power under dry and high-wind weather. The power company acknowledged that downed power lines appear to have started a fire that morning, to which firefighters responded. The company laid further blame with the county, calling the lawsuit “factually and legally irresponsible” and claiming it had de-energized power lines before another fire began in the afternoon.

Backdropped by a warming climate, many Maui residents and experts also point to ongoing commodification of land and water as having created tinderbox conditions in Lahaina, where former plantation fields lie fallow and are often covered with highly flammable nonnative grasses.

Shelley Polson used to let her dogs run through those empty acres.

She found one of them, Shadow, after the fire. But Rebel is still lost.

Tourist haven – and home

Under a tent in Napili Park, Ms. Polson sits beside boxes of pineapples. Originally from British Columbia, Ms. Polson moved to Lahaina about 40 years ago.

“It just looked like my hometown, and everything was warm,” she says. “I made some really good friends through the years.” Her roommate is among those who died.

For years Ms. Polson worked at a gift shop in a commercial strip close to the ocean. Nearby grew the sprawling 150-year-old banyan tree, scorched but still standing, where people could gather under its branches to eat rainbow-colored shave ice. Christina Nakihei, who went to high school here, worked at a fudge shop close by.

“Everyone is looking out for everyone” in Lahaina, says Ms. Nakihei, who now lives in Seattle. “Community members would stop and say, ‘Hey, do you want a ride?’”

Lahaina, along with nearby areas of West Maui, in 2022 contributed $2.9 billion of visitor expenditures – 15% of the state total. Now, however, visiting is discouraged as ashen rubble remains, and residents are wary of land grabs by outsiders.

Lahaina resident Raynard Delatori, who evacuated but whose home was spared, has already felt disrespected. The week following the fire, Mr. Delatori says he received two calls from unknown parties asking if he wanted to sell.

“For me, it’s like, seriously?” says Mr. Delatori. “At this time?”

Since then, an emergency proclamation signed by Democratic Gov. Josh Green makes it a crime to offer an unsolicited bid to a property owner located in certain Maui ZIP codes. Affordable housing is tight on the island, as it is across the state. The median sale price of a Lahaina home last month was $1 million, according to tracking by Redfin.

At the same time, the governor has also appealed to tourists to keep vacationing in Hawaii – while avoiding West Maui. But the thought of tourism now, and its role in recovery, is difficult for some Hawaii residents to embrace.

Some tourists empathize. “I understand that,” says Ed Beykovsky in Kihei, south of Lahaina, as he pauses his vacation to help.

The visitor from Oregon unloads a car of diapers, baby formula, and two-way radios that his family bought to ship to those in need by boat – one of multiple trips. The weekend before the fire, he and his wife, Kathy, had gotten breakfast in Lahaina, his sixth trip to the town. He’s now back home.

What will recovery look like?

It’s unclear what version of Lahaina Mr. Beykovsky and others might encounter in future years, much less what awaits locals when rebuilding is complete. For now, grief runs deep.

“There’s this contention between real estate development versus returning the land” to more traditional uses like farming, says Dr. McGregor, the ethnic studies professor. “What vision will prevail?”

For now, a vision of neighborly care. In a mint-green house a few blocks from Ms. Williams, Steve McQueen has stockpiled goods to distribute, too. Quick to smile and offer water, he stayed behind to help others who remain.

“I cannot leave them,” he says.

Neither has he left the doves, the ones in his driveway. A neighbor used to feed them, but that house burned. Now the birds have nowhere to go, Mr. McQueen explains.

That’s why, each day, he brings them bread and oats.

Isolated Russia looks to Africa as land of opportunity

Shunned by the West over its war in Ukraine, Russia is looking to Africa to find new international partners. And, lacking colonial history on the continent, Moscow is finding a more welcoming audience.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When a military junta seized power in Niger last month, its supporters carried Russian flags as they marched to demand that one-time colonial power France end its interference in their country. It was likely a welcome scene in the Kremlin.

Russia has returned to Africa with serious geopolitical purpose after a long post-Cold War hiatus, presenting itself as an anti-colonial alternative to the West.

The war in Ukraine has increased the sense of urgency for Moscow to intensify its activities in Africa. But it is also a source of criticism for some African leaders. Some have expressed dismay over Russia’s renewed blockade of Ukrainian grain exports, which threatens to drive up global food prices.

Russia’s trade with Africa is growing rapidly, as are political and security cooperation in many areas. And events like the coup in Niger illustrate the potential for Moscow to expand its influence at the expense of the Western powers that have traditionally dominated the continent.

“Africa has huge potential for economic growth,” says Dmitry Suslov, a foreign affairs expert. “It’s a natural partner for Russia, which has never been a colonial power in Africa. We have a lot to offer of what Africa needs, including agricultural goods, fertilizers, arms, and security assistance.”

Isolated Russia looks to Africa as land of opportunity

When Russian President Vladimir Putin addressed delegates from 49 African countries last month at the Russia-Africa Summit in St. Petersburg, he made a point to strongly remind them of the former Soviet Union’s staunch support for African anti-colonial movements in the last century.

At the same time, a military coup in the Sahel nation of Niger, supported by crowds waving Russian flags, was overthrowing yet another pro-Western African leader and attempting to curb France’s longtime influence in the region.

Russia has returned to Africa with serious geopolitical purpose after a long post-Cold War hiatus. Though these new foreign policy priorities appeared earlier and have global implications, the war in Ukraine has increased the sense of urgency for Moscow to intensify its activities in Africa.

Still, the Kremlin seems to be facing a headwind, at least temporarily, in part because of that war. Just 17 African heads of state attended the July summit presided over by Mr. Putin, far down from the 43 who showed up for the first such meeting in 2019. Some delegates expressed dismay over Russia’s renewed blockade of Ukrainian grain exports, which threatens to drive up global food prices.

But Russia’s trade with Africa is growing rapidly, as are political and security cooperation in many areas, and events like the coup in Niger illustrate the potential for Moscow to expand its influence at the expense of the Western powers that have traditionally dominated the continent.

“The growing importance of Africa is part of a reorientation of Russian foreign policy toward the non-Western world, or what Russia calls the ‘global majority,’” says Dmitry Suslov, a foreign affairs expert with the Higher School of Economics in Moscow. “Russian relations with the West are in total collapse, and are unlikely to recover in the foreseeable future. Russian policy toward the West these days is to mitigate risks, limit the damage to ourselves, and inflict damage on them. Positive policies, involving trade and cooperation, are only directed toward non-Western countries. Africa is a critical element of the non-West in Russian eyes.

“Africa has huge potential for economic growth,” Mr. Suslov adds. “It’s a natural partner for Russia, which has never been a colonial power in Africa. We have a lot to offer of what Africa needs, including agricultural goods, fertilizers, arms, and security assistance.”

A changing attitude

The new level of diplomatic outreach was on full display at the July St. Petersburg meeting, where Mr. Putin held a special session with several African leaders to hear their concerns about Russia’s war in Ukraine and to assure them that Moscow is open to peace negotiations.

“I know that you are earnestly seeking to provide assistance in reaching a just and sustainable solution to the conflict,” he told them. “We greatly appreciate your balanced approach, as well as the fact that you have not supported the anti-Russian rhetoric and anti-Russian campaign.”

Mr. Putin also sought to defuse criticisms over Russia’s blockade on Ukrainian grain by offering to step up Russian food exports, including providing thousands of tons of free grain to six African countries.

Until the crisis around Ukraine erupted in 2014, Russian involvement in Africa was mostly represented by Russian companies competing with many other global interests for access to African resources. The former Soviet Union’s ideological interests seemed long gone, along with most of its political and military clout on the continent.

“Lately Moscow has wanted to improve relations on various levels with African countries, to change the attitude toward Russia. We are ready to invest in that,” says Ivan Loshkaryov, an Africa expert with MGIMO University, which trains Russian diplomats. State-to-state relations are getting more attention, but Russian universities are also stepping up their exchanges with African counterparts, and Russian cultural centers are being established in many countries.

Russia is also increasingly an arms supplier to African countries, primarily Algeria and Egypt. But in recent years it has also retailed security services to countries like Mali, Sudan, Burkina Faso, the Central African Republic, and Angola.

Much attention has focused on the private Wagner forces, the biggest of several Russia-based private military contractors, who’ve been active in the Sahel region. Dr. Loshkaryov says that formal military cooperation involving Russia’s Ministry of Defense has lately become important, and is likely to become more so in the wake of Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin’s demise.

Moscow is also taking on at least a whiff of the former Soviet Union’s ideological appeal, riding on the anti-Western and especially anti-French feelings surging in impoverished and conflict-ridden West African and Sahel countries. There have been nine attempted coups – five of them successful – in the region in the past three years, with new military regimes wielding potent anti-colonial rhetoric.

“Widening our circles of friends”

Andrey Klimov, deputy head of the international affairs committee of the Federation Council, Russia’s upper house of parliament, says the West itself is to blame for the growth of resentments among Africans over neocolonialism.

“I visit Africa often in the framework of my inter-parliamentary work, and I know that a lot of discussions are going on” about neocolonialism and economic exploitation, he says. “Especially in the past three years, Russia’s approach to Africa has become extremely serious.”

Experts estimate that there are at least half a million people in Africa today who graduated from Soviet universities during the Cold War, when the USSR expended massive resources to foster exchanges, support Marxist-leaning regimes, and build giant infrastructure projects.

“Russia is well remembered there, especially among the older generation,” says Mr. Klimov. “We are constantly widening our circles of friends, and nowadays we are doing some of the things we used to do a long time ago. What used to be conversations and study trips are becoming real actions.”

Last week’s summit of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) economic group of non-Western nations in Johannesburg saw the admission of six new members, including the African states of Egypt and Ethiopia. Though Mr. Putin did not attend the event – perhaps worried about an international arrest warrant – experts say that Moscow is satisfied with the event, especially the general mood of disaffection for the West and support for anti-American policies, such as efforts to replace the U.S. dollar as the global reserve currency.

“The BRICS is a major priority direction for Russian diplomacy, an important non-Western grouping that shares the general vision of a post-hegemonic world, a truly multi-polar order,” says Mr. Suslov. “The BRICS is the avant-garde of the global majority, and Russia is very enthusiastic about its enlargement.”

As for the current tensions around Niger – where the West African regional bloc, ECOWAS, led by Nigeria is threatening to intervene to reverse last month’s military coup – Russian experts insist that Moscow had little to do with events there, has no intention of sending in even private security forces, and that Russian official policy actually supports the “restoration of constitutional order” there, even though it strongly opposes military intervention.

In other areas where Wagner and other private Russian military forces are active, the likelihood is that Moscow intends to put them on a much shorter leash in future, says Mr. Suslov.

“There is a process of turning Wagner into a tool of the Kremlin, directed more strictly from Moscow,” he says. “But it will remain in Africa, definitely, with work to do.”

Schools confront a generation’s worth of lost math progress

Sluggish growth in math scores for U.S. students began before the pandemic, but the problem has snowballed into an education crisis. Over the next two months, the Monitor, in collaboration with seven other newsrooms, will be documenting the challenges – as this first piece does – and highlighting examples of progress in a series called The Math Problem.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

-

By Jackie Valley The Christian Science Monitor

-

Ariel Gilreath The Hechinger Report

-

Claire Bryan The Seattle Times

-

Trisha Powell Crain AL.com

-

Maura Turcotte The Post and Courier

-

Talia Richman The Dallas Morning News

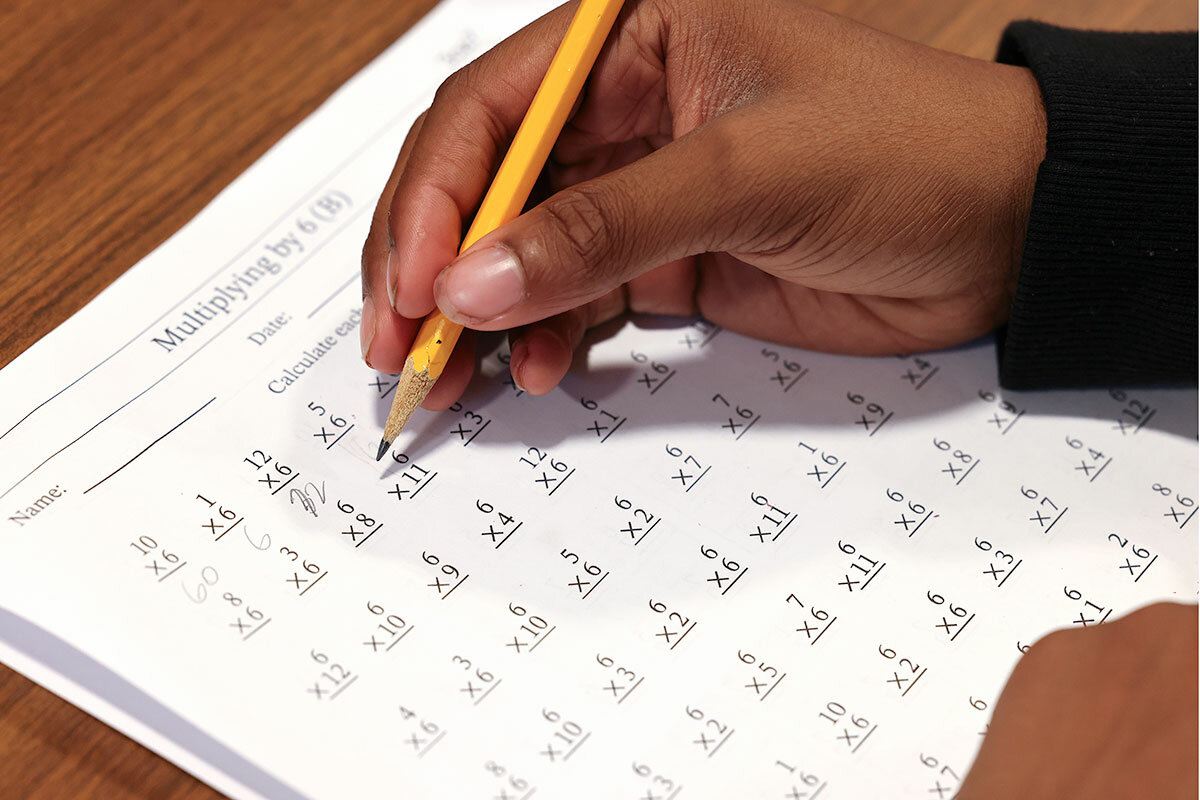

Across the United States, schools are scrambling to get students caught up in math as post-pandemic test scores reveal the depth of kids’ missing skills.

Children lost ground on reading tests, too, but the math declines were particularly striking. Math skills plummeted across the board, exacerbating racial and socioeconomic inequities in math performance that existed before the pandemic. And students aren’t bouncing back as quickly as educators hoped, supercharging worries about how they will fare as they enter high school and college-level math courses that rely on strong foundational knowledge.

Students had been making incremental progress on national math tests since 1990. But over the past year, data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the “nation’s report card,” showed that fourth graders and eighth graders’ math scores slipped to the lowest levels in about 20 years.

Using federal pandemic relief money, some schools have added tutors, offered extended learning programs, made staffing changes, or piloted new curriculum approaches in the name of academic recovery.

“We need to provide earlier intervention for students,” says Sarah Powell, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin, “or we also need to think in middle school and high school, how are we supporting students?”

Schools confront a generation’s worth of lost math progress

On a breezy July morning in South Seattle, a dozen elementary-aged students run math relays behind Dearborn Park International School.

One by one, they race to a table where a tutor watches them scribble down the answers to multiplication questions before sprinting back to high-five their teammate. These students are part of a summer program run by nonprofit School Connect WA, designed to help them catch up on math and literacy skills they lost during the pandemic. There are 25 students in the program hosted at the elementary school, and all of them are one to three grades behind.

James, age 11, couldn’t do two-digit subtraction last week. Thanks to the program and his mother, who has helped him each night, he’s caught up.

“I don’t really like math but I kind of do,” James says. “It’s challenging but I like it.”

Across the country, schools are scrambling to get students caught up in math as post-pandemic test scores reveal the depth of kids’ missing skills. On average students’ math knowledge is about half a school year behind where it should be, according to education analysts.

Children lost ground on reading tests, too, but the math declines were particularly striking. Experts say virtual learning complicated math instruction, making it tricky for teachers to guide students over a screen or spot weaknesses in their problem-solving skills. Plus, parents were more likely to read with their children at home than practice math.

The result: Students’ math skills plummeted across the board, exacerbating racial and socioeconomic inequities in math performance that existed before the pandemic. And students aren’t bouncing back as quickly as educators hoped, supercharging worries about how they will fare as they enter high school and college-level math courses that rely on strong foundational knowledge.

Students had been making incremental progress on national math tests since 1990. But over the past year, data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, known as the “nation’s report card,” showed that fourth graders and eighth graders’ math scores slipped to the lowest levels in about 20 years.

“Another way to put it is that it’s a generation’s worth of progress lost,” says Andrew Ho, a professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

At Moultrie Middle School in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Jennifer Matthews has seen the pandemic fallout in her eighth grade classes.

Some days this past academic year, for example, only half of her students in a given class did their homework.

Ms. Matthews, who is entering her 34th year of teaching, says in the last few years, students seem indifferent to understanding her pre-Algebra and Algebra I lessons.

“They don’t allow themselves to process the material. They don’t allow themselves to think, ‘This might take a day to understand or learn,’” she says. “They’re much more instantaneous.”

And recently students have been coming to her classes with gaps in their understanding of math concepts. Working with basic fractions, for instance, continues to stump many of them, she says.

Because math builds on itself more than other subjects each year, students have struggled to catch up, says Kevin Dykema, president of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. For example, if students had a hard time mastering fractions in third grade, they will likely find it hard to learn percentages in fourth grade.

Math teachers will play a crucial role in helping students catch up, but finding those teachers in this tight labor market is a challenge for many districts.

“We’re struggling to find highly qualified people to put in the classrooms,” Mr. Dykema says.

“How are we supporting students?”

Like other districts across the country, Jefferson County Schools in Birmingham, Alabama, saw students’ math skills take a nosedive from 2019 to 2021, when students not only dealt with the pandemic and its fallout, but also a new, tougher math test. Math scores plunged 20 percentage points or more across 11 schools that serve middle school students.

It raised the inevitable question: What now?

Using federal pandemic relief money, some schools have added tutors, offered extended learning programs, made staffing changes or piloted new curriculum approaches in the name of academic recovery. But that money has a looming expiration date: The September 2024 deadline for allocating funds will arrive before many children have caught up.

Progress is possible in upper grades, says Sarah Powell, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin whose research focuses on teaching math. But she says it’s easy for students to feel frustrated and lean into the idea that they’re not a “math person.”

“As the math gets harder, more students struggle,” she says. “And so we need to provide earlier intervention for students, or we also need to think in middle school and high school, how are we supporting students?”

Jefferson County educators took that approach and, leveraging pandemic funds, placed math coaches in all of their middle schools starting in the 2021-2022 school year.

The math coaches work with teachers to help them learn new and better ways to teach students, while math specialists oversee those coaches. About 1 in 5 public schools in the United States have a math coach, according to federal data.

Jefferson County math specialist Jessica Silas – who oversees middle school math coaches – says she and her colleagues weren’t sure what to expect. But efforts appear to be paying off: State testing shows math scores have started to inch back up for most of the district’s middle schools.

Ms. Silas is confident they’re headed in the right direction in boosting middle school math achievement, which was a challenge even before the pandemic. “It exacerbated a problem that already existed,” she says.

Ebonie Lamb, a special education teacher in Pittsburgh Public Schools, says it’s “emotionally exhausting” to see the inequities between student groups and try to close those academic gaps. Her district, the second-largest in Pennsylvania, serves a student population that is 53% African American and 33% white.

But she believes those gaps can be closed through culturally relevant and differentiated teaching. Ms. Lamb says she typically asks students to do a “walk a mile in my shoes” project in which they design shoes and describe their lives. It’s a way she can learn more about them as individuals.

“We have to continue that throughout the school year – not just the first week or the second week,” she says.

Ultimately, Ms. Lamb says those personal connections help on the academic front. Last year, she and a co-teacher taught math in a small group format that allowed students to master skills at their own pace. By the time February rolled around, Ms. Lamb says she observed an increase in math self-esteem among her students who have individualized education plans. They were participating and asking questions more often.

“All students in the class cannot follow the same, scripted curriculum and be on the same problem all the time,” she says.

Memorization vs. understanding concepts

Adding to the complexity of the math catch-up challenge is debate over how the subject should be taught. Over the years, experts say, the pendulum has swung between procedural learning, such as teaching kids to memorize how to solve problems step-by-step, and conceptual understanding, in which students grasp underlying math relationships, sometimes making these discoveries on their own.

“Stereotypically, math is that class that people don’t like. And I believe part of the reason is because for so many adults, math was taught just as memorization. You had to memorize exactly what to do, and there wasn’t as much focus on understanding the material,” says Mr. Dykema, of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. “And I believe that when people start to understand what’s going on, in whatever you’re learning but especially in math, you develop a new appreciation for it.”

Ms. Powell, the University of Texas professor, says teaching math should not be an either-or situation. A shift too far in the conceptual direction, she says, risks alienating students who haven’t mastered the foundational skills.

“We actually do have to teach, and it is less sexy and it’s not as interesting,” she says.

Diane Manahan, a mother from Summit, New Jersey, says she watched the pandemic chip away at her daughter’s math confidence and abilities. Her daughter, a rising sophomore, has dyscalculia, a math learning disability characterized by difficulties understanding number concepts and logic.

For years, Ms. Manahan paid tutors to work with her daughter, a privilege she acknowledges many families could not afford. But, Ms. Manahan says, the problems in math instruction are not limited to students with learning disabilities. She often hears parents complain that their children lack basic math skills, or are unable to calculate time or money exchanges.

Ms. Manahan wants to see school districts overhaul their curriculum and approach to emphasize those foundational skills.

“If you do not have math fluency, it will affect you all the way through school,” she says.

Halfway across the country in Spring, Texas, parent Aggie Gambino has often found herself searching YouTube for math videos. Giada, one of her twin 10-year-old daughters, has dyslexia and also struggles with math, especially the word problems. Ms. Gambino says she has strong math skills, but helping her daughter has proved challenging, given instructional approaches that differ from the way she was taught.

She wishes her daughter’s school would send home information to walk parents through how students are being taught to solve problems.

“The more parents understand how they’re being taught, the better participant they can be in their child’s learning,” she says.

Stepping back, moving forward

It doesn’t take high-level calculations to realize that schools could run out of time and pandemic aid before math skills recover. With schools typically operating on nine-month calendars, some districts are adding learning hours elsewhere.

Lance Barasch recently looked out at two dozen incoming freshmen and knew he had some explaining to do. The students were part of a summer camp designed to help acclimate them to high school.

The math teacher works at the Townview School of Science and Engineering, a Dallas magnet school. It’s a nationally recognized school with selective entrance criteria, but even here, the lingering impact of COVID-19 on students’ math skills is apparent.

“There’s just been more gaps,” Mr. Barasch says.

When he tried to lead students through an exercise in factoring polynomials – something he’s used to being able to do with freshmen – he found that his current group of teenagers had misconceptions about basic math terminology.

He had to stop to teach a vocabulary lesson, leading the class through the meaning of words like “term” and “coefficient.”

“Then you can go back to what you’re really trying to teach,” he says.

Mr. Barasch wasn’t surprised that the teens were missing some skills after their chaotic middle school years. His expectations have shifted since the pandemic: He knows he has to do more direct teaching so that he can rebuild a solid math foundation for his students.

Filling those gaps won’t happen overnight. For teachers, moving on from the pandemic will require a lot of rewinding and repeating. But the hope is that by taking a step back, students can begin to move forward.

Editor’s note: This piece is the first in a series about math education from the Education Reporting Collaborative, a coalition of eight diverse newsrooms: AL.com, The Associated Press, The Christian Science Monitor, The Dallas Morning News, The Hechinger Report, Idaho Education News, The Post and Courier in South Carolina, and The Seattle Times.

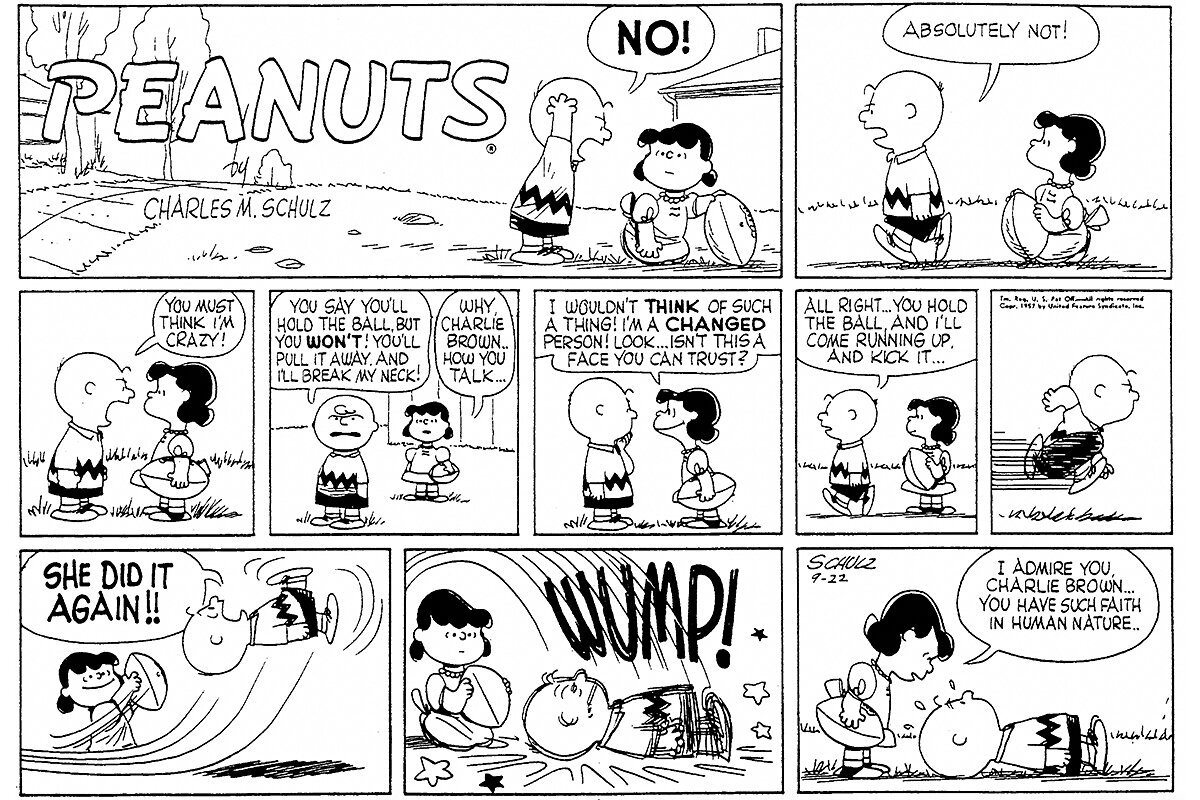

‘Peanuts,’ Charles Schulz, and the state that started it all

What more is there to learn about Charlie Brown’s football and Woodstock’s birdbath? An exhibit about cartoonist Charles Schulz offers a unique window into his inspiration: the Midwest.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

“Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz moved to California later in life, but he spent his formative years in Minnesota.

The state provided a backdrop for what would become well-known storylines: autumn leaves piling up during football games, Woodstock ice-skating on a frozen birdbath, or the cast of characters racing across a hockey rink.

Mr. Schulz credits his high school art teacher for spotting his talent and encouraging him to follow his own voice. A black-and-white photo of her from 1940 is one of more than 150 letters, photos, and memorabilia on view as part of a yearlong exhibit, “The Life and Art of Charles M. Schulz” at the Minnesota History Center in St. Paul.

The artist’s enduring creations contributed to American pop culture and offered poignant life lessons for generations: how to make lemonade out of lemons, and that perseverance wins out.

“The world that Schulz built had kids talking like adults about big things: life, death, and God,” says Mark Fearing, an author and illustrator in Portland, Oregon, whose family grew up alongside Mr. Schulz in the St. Paul area. “‘Peanuts’ was radically different. ... It was a revolution.”

‘Peanuts,’ Charles Schulz, and the state that started it all

“Come on, Charlie Brown. I’ll hold the ball and you kick it.”

Readers might be surprised that “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz was among those hoping that – maybe, just maybe – Lucy van Pelt would finally let Charlie Brown kick the football.

Although the “Peanuts” cast are thought to be different facets of Mr. Schulz’s personality, he said that they had a life of their own.

“He often spoke about the characters as leading independent lives,” says Chip Kidd, a New York-based graphic designer who published two books on Mr. Schulz’s work. “In one interview he said, ‘I wish Lucy would let Charlie Brown kick the football.’ I don’t think he was trying to be sarcastic. In his mind, the characters did take over.”

Just as Charlie Brown had to learn to pick himself up from failure, so too did Mr. Schulz as a shy, small kid growing up in St. Paul, Minnesota. Mr. Schulz credits his high school art teacher, Minnette Paro, for spotting his talent early on and encouraging him to follow his own voice.

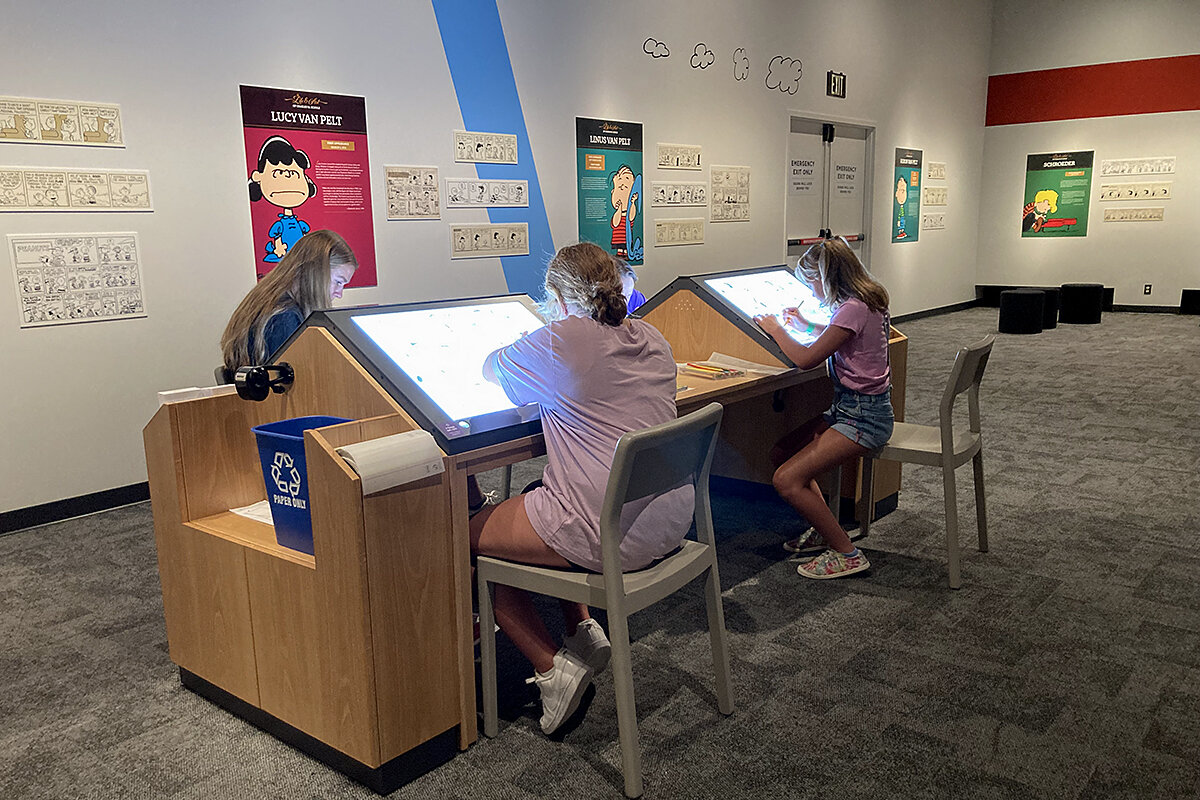

A black-and-white photo of Ms. Paro from 1940 sits in a glass case at the Minnesota History Center, one of more than 150 letters, photos, and memorabilia on view as part of a yearlong exhibit, “The Life and Art of Charles M. Schulz” in St. Paul.

While fans of the iconic comic strip will appreciate the more familiar elements on display – a Snoopy-inspired Pez dispenser, a 1980s-era lunchbox – it is the exhibit’s ode to the Midwest that offers a unique window into Mr. Schulz’s inspiration.

Though he later moved to California, Mr. Schulz spent his formative years in Minnesota, which provided a backdrop for what would become well-known storylines: autumn leaves piling up during football games, Woodstock ice-skating on a frozen birdbath, or the cast of characters racing across a hockey rink.

Those Minnesota moments set the stage for an artist whose enduring creations contributed to American pop culture and offered poignant life lessons for generations: how to make lemonade out of lemons, and that perseverance wins out.

“The world that Schulz built had kids talking like adults about big things: life, death, and God,” says Mark Fearing, an author and illustrator in Portland, Oregon, whose family grew up alongside Mr. Schulz in the St. Paul area. “But there were also things that felt like part of my landscape: homes, a dog, kids going to school on a school bus. ‘Peanuts’ was radically different. ... It was a revolution.”

Midwestern influence

Mr. Schulz was born in Minneapolis in 1922 and began publishing cartoons regularly in 1947 with his weekly series of one-panel jokes, “Li’l Folks,” in the St. Paul Pioneer Press. It was here that Mr. Schulz created the name Charlie Brown as well as a dog that resembled Snoopy. After “Li’l Folks” was dropped in 1950, Mr. Schulz developed a four-panel comic strip for syndication, and “Peanuts” was born.

Over the next 50 years, Mr. Schulz would produce 17,897 “Peanuts” strips. He proudly maintained full editorial control over the cartoon, sitting down every morning with a yellow legal pad and coming up with the lettering, storyline, imagery, and colors – something rare at the time that, some say, alluded to his upbringing.

“There is the stereotype of the Midwest work ethic, and it was all over his strip,” says Annie Johnson, museum manager at the Minnesota Historical Society, an educational nonprofit that oversees more than two dozen historic sites and museums, including the Minnesota History Center. “I think people from here will also recognize repeating [Midwestern] themes of self-deprecating humor and modesty.”

Mr. Schulz took a piece of Minnesota with him when he moved his family to California in 1958, building a new ice hockey rink in a neighborhood of Santa Rosa, which opened to the public in 1969. In 2002, Santa Rosa opened the Charles M. Schulz Museum to celebrate the artist, which provided the wall panels for the Minnesota exhibit.

The panels describe all of the major “Peanuts” characters, from fan favorite Snoopy to boundary-breaking characters like Franklin – the strip’s first person of color, who appeared in 1968 – and Peppermint Patty, who in the 1960s wore shorts instead of dresses and chose sports over school any day.

“A piece of ourselves in each character”

The lessons that “Peanuts” characters taught readers through humor and metaphor – often involving unrequited love, sports, and friendship – were what made them so beloved. It’s also given the comic an enduring popularity even as print newspapers fade.

“Comic strips were a unifying, recognizable expression found in newspapers that blanketed the whole country. They had a huge impact,” says Mr. Fearing. “There’s nothing comparable now.”

Still, the St. Paul exhibit hopes to inspire a new generation of “Peanuts” fans, some of whom may have only seen the still-popular “A Charlie Brown Christmas” animated TV special. Since the exhibit opened in July, summer camps-ful of schoolchildren have visited, as have many grandparents with their grandchildren.

“Kids today might not get it as much as we do. They didn’t grow up with these memories,” says Annette Gilles, who visited the exhibit with her husband, Don, and 9-year-old grandson in early August. “But [‘Peanuts’] taught us things. We felt like we had a piece of ourselves in each character.”

For Minnesotans, those feelings are especially strong. Curators worked with their own collection of “Peanuts” memorabilia to give the exhibit a nostalgic, local touch: There are the life-size statues from the city art project Peanuts on Parade, as well as objects from Camp Snoopy, a 7-acre amusement park that was installed in the nearby Mall of America for over a decade.

What local visitors have especially appreciated, say museum spokespersons, is knowing more about the man behind the magic. A blown-up wall map pinpoints more than a dozen of Mr. Schulz’s old haunts – his local barber shop, former schools, and family home. Ms. Johnson says longtime Twin Cities residents “can spend half an hour in front of it.”

But the Midwestern elements of the exhibit are intended to welcome – not exclude – visitors into Mr. Schulz’s universe and to add new richness to an already abundant following. At the end of July, the Peanuts Collectors Club held its 17th annual Beaglefest during the exhibit’s opening weekend in order to discover some previously unseen memorabilia.

Even if comic strips may be moving toward a thing of the past, Mr. Schulz’s cast of flawed but lovable characters continues to resonate with people in Minnesota and beyond.

“‘Peanuts’ was so real and touched everyday life,” says visitor Carol Faust, of the nearby suburb New Brighton. “There was a sense of friendly competition but without animosity. Even if Lucy was mean sometimes to Charlie Brown, all the characters accepted each other as they were. There was no hate. It’s refreshing.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

College admissions become more probing

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Earlier this month, the Biden administration offered guidelines to colleges and universities on how they can assemble a diverse student population despite a June 29 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that racial preferences in admissions are unconstitutional. The guidance is one of many attempts in American education to navigate a new legal landscape. In the wake of the court’s decision, many colleges have said they will no longer weigh scores on standardized tests. Others changed the type of required essay to prompt students toward addressing personal experiences such as race, parental education, or poverty.

These efforts are signs that many schools will focus more on each applicant’s character than on group identity. Schools that focus on how applicants overcame adversity, for example, are really probing those prospective students’ qualities of thought, such as honesty, compassion, and discernment. An initiative launched after the court ruling by the National Association for College Admission Counseling seeks to advance the role that character plays in the admission process and to find a reliable, objective way to measure such qualities.

“We’re only capturing what’s on the surface when it comes to students’ strengths and potential,” says David Hawkins, the association’s chief education and policy officer.

College admissions become more probing

Earlier this month, the Biden administration offered guidelines to colleges and universities on how they can assemble a diverse student population despite a June 29 ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that racial preferences in admissions are unconstitutional. The official guidance allows schools to consider difficulties in an applicant’s life and education – including race.

The guidelines are one of many attempts in American education to navigate a new legal landscape. In the wake of the court’s decision, many colleges have said they will no longer weigh scores on standardized tests, which statistics show favor students from affluent families. Others have dropped legacy admissions or changed the type of required essay to prompt students toward addressing personal experiences such as race, parental education, or poverty.

These efforts are signs that many schools will focus more on each applicant’s character than on group identity. Ending racism, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the court decision, requires citizens to “see each other for what we truly are: individuals with unique thoughts, perspectives, and goals, but with equal dignity and equal rights under the law.”

Schools that focus on how applicants overcame adversity, for example, are really probing those prospective students’ qualities of thought, such as honesty, compassion, and discernment. An initiative launched after the court ruling by the National Association for College Admission Counseling seeks to advance the role that character plays in the admission process and to find a reliable, objective way to measure such qualities. The association recently joined hands with the Character Collaborative, an organization that promotes character in admissions.

“We’re only capturing what’s on the surface when it comes to students’ strengths and potential,” David Hawkins, NACAC’s chief education and policy officer, told The Chronicle of Higher Education. “The question is: How do we capture these intangibles that fall outside the things we try to quantify on paper?”

A new survey of high school and college admissions officials by the association found that more than two-thirds set considerable or moderate importance to an applicant’s positive character attributes. “What we’re trying to do through the character collaborative is have institutions talk about what are the character traits, what’s important to build our community,” Tom Bear, vice president for enrollment management at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, told the Tribune-Star in Terre Haute, Indiana. “Let’s communicate that to prospective students, so they can do a better job of identifying those themselves and saying, what’s the right fit.”

The era of strictly race-based preferences in college admissions is over. But a new era in education may have begun, one that requires a deeper understanding of what students and schools can better offer each other.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A new view of home

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Mark Swinney

Recognizing that our true dwelling is spiritual reveals greater security and richness in our experience of home.

A new view of home

It can be helpful to expand one’s overall definition of home – to consider it as something more than a physical place. While we might need to focus on the practicalities of home building, home repair, along with home buying and selling, there’s a bigger, spiritual view that home is truly about. It’s a perspective that can also throw healing light on issues such as home loss and homelessness.

Jesus encouraged people, “Lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt” (Matthew 6:20). The home that is a heavenly treasure is far more than even the most loved house, tent, or mansion. Christian Science teaches that we each as God’s valued children have an inseparable oneness with God, divine Spirit, which means that the consciousness of being in God’s presence is our true and invulnerable home.

This is a home that is fully and beautifully furnished – not with physical things, but with a multitude of spiritual elements. We as spiritual ideas of Mind, another name for God, have this spiritual home, including all of its good furnishings. Spiritual joy, rest, nourishment, and activity are just some of them! These spiritual elements not only comfort us, but they also strengthen us and even impel us to help others. “The man of God may be perfect, throughly furnished unto all good works,” as the Bible puts it (II Timothy 3:17).

Our permanent, forever abode is our oneness with God. We are never truly away from this home. It cannot be taken from us or destroyed. Our habitation here in the all-presence of heaven is assured.

Understanding this expanded view of home, even if only a glimpse, brings such confidence. An article from the Christian Science Sentinel, a sister publication to the Monitor, describes how a family proved this to be true in a beautiful way (see Vicki A. Turpen, “What we gained when we lost everything,” February 22, 1999). The writer’s storage shed and partially-built house had burned to the ground.

As a Christian Scientist, her prayers took her to the book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.” She notes where the author, Monitor founder Mary Baker Eddy, writes, “Home is the dearest spot on earth, and it should be the centre, though not the boundary, of the affections” (p. 58).

Through prayer, the family found a contractor to quickly rebuild their house, but the writer also says the center of home “is a spiritual idea, not a physical structure. As each family member recognized this spiritual truth, the feeling of loss was replaced with the assurance that God was still present and accountable. No human loss could erase this fact. Our home became a much happier, healthier place than it had been, and over the next few years it became a haven for other young people who were attracted to our family because of the qualities the children expressed.”

Into our heavenly home, none of the world’s fears gain entrance. Divine consciousness, the basic substance of our holy abode, always remains pure. We have the right to rejoice often then, because, as the 91st Psalm puts it, we continuously and safely “abide under the shadow of the Almighty” and dwell in “the secret place of the most High” (verse 1).

From our heavenly home, is there ever a moving day? Absolutely not. Mrs. Eddy once said to the members of her household: “Home is not a place but a power. We find home when we arrive at the full understanding of God” (Irving C. Tomlinson, “Twelve Years with Mary Baker Eddy,” Amplified Edition, p. 211).

As God’s ideas, we dwell permanently and safely in God. There is no departing from, nor losing, this heavenly home, since God is ever present. We can increasingly become conscious of, and be so grateful for, how we each – all around the world – are truly God’s ideas, forever residing in the perfect spiritual home that is God.

Viewfinder

Battening down for Idalia

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow when the Monitor’s Story Hinckley takes a unique look at the growing urban-rural divide in U.S. politics. As the two political parties continue to grow further apart ideologically, conservative pockets in liberal states are feeling unheard and overpowered. The solution, to some voters in eastern Oregon, is secession.