- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A new wild card in Taiwan elections

The idea that a self-made billionaire should run for president, in part because he or she isn’t beholden to parties or donors, always struck me as an American conceit. Think Ross Perot or Michael Bloomberg, neither of whom went the distance. Donald Trump’s candidacy ended up being as much about celebrity as business acumen.

Now Taiwan is hearing the siren call of the tycoon-as-president. Terry Gou founded Foxconn, the electronics manufacturer that assembled the iPhone in your pocket. This week, he said he will run as an independent in January’s presidential election.

Mr. Gou’s candidacy isn’t a complete surprise. He has flirted with presidential runs in the past, and he tried to win the nomination of the main opposition party, the Kuomintang. But his late entry presents a wild card. Critics say Mr. Gou will simply split the opposition and hand victory to the current front-runner, William Lai of the Democratic Progressive Party.

The world will be watching, given the tensions over China’s territorial claims on Taiwan. While the Democratic Progressive Party favors independence, the Kuomintang is more conciliatory. Mr. Gou’s extensive business interests in China and personal ties to its leadership have also raised eyebrows. At his announcement, Mr. Gou said he had no “partisan baggage” and would seek peace not war with China. “The people’s interests are my biggest interests,” he said.

His message may resonate with some voters. But those who view Beijing skeptically will likely need persuading that a business leader, not a politician, knows how best to navigate the stormy waters between Taiwan and China.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Protesters in Peru fight indifference

Nearly a year after a president’s dramatic coup attempt and impeachment, Peruvians want to vote for their next president before the scheduled 2026 elections. Legislators are trying to look the other way.

-

By Manuel Rueda Contributor

Peru has churned through six presidents in the past seven years. But the nation’s political crisis worsened at the end of last year, when Congress impeached then-President Pedro Castillo, a left-wing teacher with Indigenous roots who upended Peru’s conservative establishment when he won the 2021 election. Mr. Castillo’s removal came just hours after he illegally attempted to dissolve Congress and rule by decree in the face of a corruption probe – what many considered an attempted coup.

The impeachment complied with Peruvian laws, but it unleashed protests in parts of Peru’s Andean highlands, where his initial victory had felt like a long-awaited recognition of the nation’s poor and Indigenous communities.

Some 80% of Peruvians want early elections, according to a July poll by the Institute of Peruvian Studies, a research group. As the crisis endures, legislators’ refusal to entertain requests for new elections has generated nationwide resentment toward political elites, which in turn is making Peru harder to govern, experts say.

“Congress is only defending its own interests,” says Jarek Tello, a lawyer and member of the centrist Purple Party. “What we are trying to do ... is to force Congress to respond to the will of the people.”

Protesters in Peru fight indifference

Jarek Tello is outfitted with a megaphone and clipboard as he navigates a crowd of protesters in the capital’s city center on a recent afternoon. His mission? Gather enough signatures to push Congress to move up national elections, currently scheduled for 2026.

The lawyer and activist for Peru’s centrist Purple Party knows it’s a big ask: If elections are moved up, current members of Congress would lose their seats. But like many protesters here today, Mr. Tello argues that holding early elections is the only way to save Peru from an increasingly powerful clique of legislators that many believe is undermining the nation’s democracy.

Peru has churned through six presidents in the past seven years. But the nation’s political crisis worsened at the end of 2022, when Congress impeached then-President Pedro Castillo, a left-wing teacher with Indigenous roots who upended Peru’s conservative establishment when he won the 2021 election. Mr. Castillo’s removal came just hours after he illegally attempted to dissolve Congress and rule by decree in the face of a corruption probe.

The impeachment complied with Peruvian laws, but it unleashed protests in some parts of Peru’s Andean highlands. Mr. Castillo’s initial victory was celebrated in these areas as a historic moment of recognition for the nation’s long-ignored impoverished and Indigenous communities. His removal felt like yet another slight against these groups and has diminished the government’s ability to operate in these regions.

Some 80% of Peruvians want early elections, according to a July poll by the Institute of Peruvian Studies, a research group. As the crisis endures, legislators’ refusal to entertain requests for new elections has generated resentment – including in the capital – toward political elites, which in turn is making the nation harder to govern, experts say. Protests and roadblocks are expected to continue.

“Congress is only defending its own interests,” Mr. Tello says. “What we are trying to do with this petition is to force [legislators] to respond to the will of the people.”

A lack of incentives?

In cities such as Juliaca and Ayacucho, the protests following Mr. Castillo’s impeachment were met with brutal force from police who used firearms on demonstrators and even shot bystanders, turning public opinion squarely against newly appointed interim President Dina Boluarte. According to Peru’s human rights ombudsperson, 49 people were killed by gunfire in protests that took place between December 2022 and February 2023. The demonstrations also hurt the economy and forced the government to close some of Peru’s famous archaeological sites.

Although the intensity of the protests has diminished, roadblocks continue periodically in the south of the country, and several marches were held at the end of July in Lima, coinciding with the celebration of Peru’s Independence Day.

Protesters say they are outraged with the lack of progress shown by investigations into the killings, which have not resulted in any convictions so far. But increasingly, citizen frustration is directed toward what feels like a democratic backslide prompted by Peru’s increasingly powerful Congress, which only has an approval of 6%, according to the July poll.

“Members of Congress are making laws for their own benefit and stopped representing us a long time ago,” says Antonia Quisocapa, an Indigenous leader from the region of Puno who traveled to Lima to protest last month. She says President Boluarte should resign: “She’s got her hands full of blood.”

Over the past six months, Peru’s Congress has struck down motions filed by Ms. Boluarte to hold early elections and advanced a law that would enable legislators to remove the judges who preside over Peru’s electoral system. Congress has levied questionable corruption charges against three of the seven magistrates that run the National Judiciary Council, which is in charge of appointing judges to courts nationally.

Rosa María Palacios, an influential columnist and lawyer, describes these moves as an “assault” on Peru’s democracy that is eroding checks and balances. “Congress is using its powers abusively and in a totalitarian manner,” she says.

There are few incentives for Peru’s Congress to approve a law that would activate early elections, says Ms. Palacios. Legislators are constitutionally barred from reelection here, which means if elections come early, they would be putting themselves out of work.

The latest effort to move up elections fizzled in February, as legislators disagreed over whether a referendum over a new constitution should also be included in an early election.

Ms. Boluarte, whose term goes until 2026, initially advocated for early elections. But, during a press conference that followed one of the July protests, she said that laws governing elections were out of her hands, suggesting Peruvians should instead complain over social and economic issues that her government could take action on.

But she could force new elections to take place – if she resigns. She has dismissed that as an option, saying she has a responsibility to fulfill her constitutional mandate and finish her presidential term. Ms. Boluarte was never voted into the presidential office. She was Mr. Castillo’s vice president and was sworn in after he was impeached. She had promised in gatherings with Mr. Castillo’s supporters that if the president were ever to be removed, she would resign.

“I think they’ve seen that they can ride out the pressure,” says Will Freeman, a political scientist at the Council on Foreign Relations who researches governance in Peru. There are other incentives for the president and many of Peru’s members of Congress to hold on to their seats, he says.

“They definitely don’t want to be investigated” for the human rights violations “that have been happening over the past six months,” Mr. Freeman says. “That also explains the whole push to control institutions.”

No guarantee

Peruvians – particularly outside big cities – have become increasingly skeptical of all levels of government over the past six months, says Glaeldys González Calanche, a Peru expert at the International Crisis Group. It’s harder for officials from the central government to implement health and security policies in partnership with regional administrations or municipal governments. On several occasions, government officials have had to leave villages or cancel meetings after locals pushed them away with rocks and sticks. Meanwhile, mayors from some towns in the south of Peru – where most of the killings of protesters occurred – have been reprimanded by their own voters for meeting with Ms. Boluarte and forced to make public apologies.

“Some people don’t believe that officials [from the central government] are real authorities any longer,” Ms. González says. “What we’re afraid of is that criminal groups could benefit from this chaotic situation.”

But many Peruvians have become “indifferent” to the political situation, particularly in a nation where political protest has historically been stigmatized and linked to leftist rebel groups, says Ms. Palacios, the lawyer. The latest round of protests in Peru’s capital were much smaller than previous ones; an estimated 20,000 people demonstrated together on July 20.

“If you come out here to protest over the deaths of civilians, they start to accuse you of being a terrorist,” says Ms. Palacios, who says a group of about 20 government supporters with megaphones recently showed up outside her home screaming insults at her for hours over her criticism in columns and on national radio programs of the Boluarte government.

Despite the lack of response to public frustration, some Peruvians are still hopeful they can pressure politicians to hold elections before 2026. Peru’s struggling economy could work in their favor.

The Peru Constitution allows citizens to present topics for congressional debate after gathering 76,000 signatures.

Mr. Tello, the lawyer for the Purple Party, and volunteers are setting up booths in the street several times a week and attending protests where they gather signatures for a petition calling for early elections. They’re even taking down the ID numbers and fingerprints of those who sign, to ensure that the petition can be legalized and, they hope, generate a public conversation among legislators.

So far, the group, which is also backed by a construction workers union, has gathered 37,000 signatures. Members are hoping to reach 76,000 by October.

“The success of this petition is not guaranteed,” Mr. Tello says. “But we will put this issue on the table once again and force legislators to confront it.”

Patterns

Putin rebounds at home, but global ambitions stymied

Vladimir Putin appears to have reasserted his authority at home, following June’s mutiny, but Russia’s international standing is taking a beating.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Russian President Vladimir Putin may have strengthened his own power at home in recent days: He is widely believed to have ordered the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the mercenary leader who rebelled two months ago and who perished in a plane crash last week.

But another Russian crash suggests that the grand geopolitical ambition that inspired Mr. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine – a reassertion of Russia’s Soviet-era status as a great world power – is looking increasingly threadbare.

On the moon, 240,000 miles from Earth, an uncrewed Russian vehicle went out of control and crashed. Moscow’s first lunar mission since 1976 had failed.

This was especially galling because, a few days later, a similar Indian mission was crowned with success. Mr. Putin was not on hand to congratulate Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who was at a diplomatic summit in South Africa. If the Russian leader had set foot there, he would have risked arrest on an international warrant as a war criminal.

Another sign of Russia’s shrinking geopolitical horizons.

Russia is now hoping to cooperate with China in space. That makes sense, but it will come at the price of reduced status.

The former superpower will be the junior partner.

Putin rebounds at home, but global ambitions stymied

It is a tale of two crashes, with a sobering message for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Which is that while Mr. Putin has reinforced his power at home in recent weeks, the grand geopolitical ambition that inspired his invasion of Ukraine – reasserting Russia’s Soviet-era status as a great world power – is looking increasingly threadbare.

Of the two Russian craft that went down this month, the one signaling the Russian president’s robust authority at home made the bigger headlines worldwide: the plane carrying Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner Group militia leader who had mutinied against Mr. Putin’s military chiefs last June, which crashed near Moscow.

In the wake of that crash, which Western intelligence analysts attributed to a bomb, Mr. Putin issued a decree requiring all militia fighters to swear allegiance to the Russian state.

Yet the other disaster underscored a longer-term challenge to the Russian president’s global aspirations – exacerbated by his failure to achieve the short, sharp victory he clearly expected when he sent his invasion forces into Ukraine 18 months ago.

That crash occurred 240,000 miles away, on the moon.

It involved an uncrewed vehicle dubbed Luna-25, launched from Russia’s Far East. Russian space engineers lost control of it two weeks ago as it descended toward the moon’s surface.

They had hoped it would land near the moon’s south pole, where scientists have detected signs of ice. Water and its constituents, hydrogen and oxygen, could permit an extended human presence on the moon, and facilitate fuel production for interplanetary exploration.

But for Mr. Putin, the launch was also intended as a geopolitical statement.

It was his country’s first lunar mission since 1976, and after a Cold War space race in which the Soviet Union had notched up spectacular triumphs – notably the world’s first crewed orbital flight, in 1961, by Yuri Gagarin.

Had this month’s lunar mission succeeded, Russia would have become the first nation to achieve a soft landing at the moon’s south pole.

Instead, according to a terse official statement, Luna-25 “moved into an unpredictable orbit and ceased to exist as a result of a collision with the surface of the moon.”

In the days afterward, Mr. Putin was confronted with reminders of how much more complicated his bid for Russian great-power influence has become amid his war against Ukraine.

First, another rising world power – India – succeeded where Russia had failed. It landed its own uncrewed craft at the moon’s south pole.

Amid worldwide messages of congratulation, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi basked in the plaudits of fellow members of the BRICS economic alliance – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa – at their summit in Johannesburg.

If there was a consolation for Mr. Putin, it was that he wasn’t there.

But the reason for his absence served only to bring home his – and his country’s – shrinking geopolitical horizons in the face of Western diplomatic and economic sanctions.

Had he gone, South Africa, as a member of the International Criminal Court, would have been obliged to arrest Mr. Putin on ICC charges of deporting Ukrainian children to Russia during the war.

This week, the Kremlin announced Mr. Putin would also skip the G20 summit in India Sept. 9.

While Mr. Putin’s decision not to travel may have been prompted by more substantial motives than reluctance to chat with Mr. Modi about moon landings, the importance that Mr. Putin attaches to space triumphs as a reflection of Russia’s place in the world is not in doubt.

He has regularly praised Mr. Gagarin’s exploits, only recently announcing a national “space achievement” award in his name. And on the 60th anniversary of the Gagarin flight, he declared that “Russia must maintain its status as one of the leading nuclear and space powers, because the space sector is directly linked to defense.”

Nor can the more fundamental contrast with India have escaped him. Russia is a larger country, with far greater reserves of oil, gas, and other resources. But India’s economy is nearly twice as big – with a much more vibrant high-tech sector, a major boost to its space program.

And India, unlike Mr. Putin’s increasingly sanctioned nation, has ready access to the array of microchips, instrumentation, and other equipment essential to space flight.

After the Luna-25 crash, the head of Russia’s space agency insisted on the need to push ahead with the program. Echoing Mr. Putin’s views, he said, “This is not just about the prestige of the country and the achievement of geopolitical goals. It is about ensuring defensive capabilities and achieving technological sovereignty.”

But he also seemed to imply limits to what Russia could achieve on its own, emphasizing plans for a joint mission with China.

The logic is clear: China, especially since the Ukraine invasion, has become Russia’s main, indispensable ally.

But while Russia has been on the moon exploration sidelines for nearly five decades, China has been mounting increasingly complex missions in recent years. It is planning a crewed flight by 2030.

So although cooperation with China in space does make sense for Russia, it will come at a price.

The former superpower will be the junior partner.

The Explainer

From Florida to California, dwindling insurance options

As parts of the United States face extreme weather from hurricanes to wildfires, many of those same places are losing access to home insurance. We explore what’s changing and why.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As Hurricane Idalia barreled through Florida Wednesday, thousands of homeowners faced the possibility of rebounding without property insurance.

In the past few years, nearly a dozen property insurers in Florida have liquidated. More have either left the state or restricted coverage, including Farmers Insurance, which pulled out of the Sunshine State last month. Other states prone to high-risk weather events are also losing insurance options. In Louisiana, two dozen insurance companies have dissolved or left since 2020. In California, three of the five largest insurers are limiting new policies or have stopped offering them altogether.

Insurers say payouts are outpacing revenue, as housing costs rise and climate change contributes to more frequent and costly disasters.

“People are purchasing and moving into much more expensive properties in environmentally sensitive areas,” says Robert Gordon of the American Property Casualty Insurance Association.

Some consumer advocates say insurance companies are creating a crisis narrative to better position themselves.

An insurance crisis is avoidable, says Carmen Balber, executive director of Consumer Watchdog. “We all know that another fire is going to hit, but that’s what the industry is here for. And we need to be investing in the meantime in reducing the risk so we don’t reach the breaking point.”

From Florida to California, dwindling insurance options

As Hurricane Idalia barreled through Florida Wednesday, thousands of homeowners faced the possibility of rebounding without property insurance.

In the past few years, nearly a dozen property insurers in Florida have liquidated. More have either left the state or restricted coverage, including Farmers Insurance, which pulled out of the Sunshine State last month. Other states prone to high-risk weather events are also losing insurance options. In Louisiana, two dozen insurance companies have dissolved or left since 2020. In California, three of the five largest insurers are limiting new policies or have stopped offering them altogether.

Insurers say payouts are outpacing revenue, as housing costs rise and climate change contributes to more frequent and costly disasters. But consumer advocates push back and say insurance companies are creating a crisis narrative to better position themselves.

Insurers are regulated by each state in which they operate, tasking insurance commissioners with balancing the needs of homeowners against the economic viability of covering losses. “There is no quick fix,” writes Michael Soller, spokesperson for California’s insurance commissioner, Ricardo Lara, in an email. He cites “entrenched interests on all sides” and says the system “is clearly not working for all Californians.” Similarly, homeowners across the country face constricting options that are growing more expensive.

Why are insurers leaving high-risk areas?

Climate change plays a significant role, but another key, immediate factor, according to the insurance industry, is the cost of housing. As home prices have lurched upward, other associated costs also increased.

In 2022, insurers paid out about $1.03 in claims for every $1 collected in premiums, according to a report by analytics company Verisk and the American Property Casualty Insurance Association. The industry’s payments and costs increased by 14.1% while premiums grew by 8.3%.

“The boom in home values is really the biggest cost driver impacting insurance rates,” says Robert Gordon, policy and research expert at the association.

Similarly, Verisk sees a mix of factors at play. In a 2022 report, it said insured losses from natural catastrophes during the most recent five years were roughly double those of the half-decade before that. The reasons cited in the report included climate change and shifting regulations, but listed first was “a rise in exposure values and replacement costs, represented both by continued construction in high-hazard areas as well as high levels of inflation that are driving up repair costs.”

“So in other words,” says Mr. Gordon, “it’s just the demographic changes as people are purchasing and moving into much more expensive properties in environmentally sensitive areas.”

But the costs are no justification for abandoning homeowners, says Carmen Balber, executive director of Consumer Watchdog, a consumer advocacy organization based in California. “That’s why Californians have paid $150 billion in home insurance premiums over the last 25 years,” she says. “So the industry would be there when we need them most.”

How does climate change affect home insurance?

Climate scientists say Earth’s warming temperatures are increasing the severity of extreme weather, alongside other factors that have pushed up the cost of natural disasters.

A recent survey by the Insurance Information Institute shows 32% of homeowners have been impacted by weather in the last five years. Weather events – from fire to wind to hail – cause the vast majority of property claims. Yet, insurers have long excluded high-risk events from policies. Congress established the National Flood Insurance Program in 1968 because most insurers excluded flood protection – and still do.

Earthquakes are excluded from standard policies, requiring supplemental coverage. Despite the fact that six of the 10 costliest U.S. earthquakes have happened in California, only 10% of the state’s homeowners carry earthquake coverage.

“Insurance companies would like to only insure the least risky people and leave the more risky people out to the periphery so they can keep only the most profitable policies and leave the ones they might have to pay on to others,” says Ms. Balber.

But the insurance industry doesn’t cause rate changes, says Mr. Gordon, nor does it tell people where to live.

The frequency of climate disasters is compounded by the migration of people moving to areas with the highest risk. National realtor Redfin reports more people are moving into disaster-prone areas than out of them. Eight of the 10 high-flood-risk counties that saw the largest net influx are on the Florida coast. And in Riverside, California, where more homes face wildfire risks than any other county analyzed, nearly 40,000 more people have moved in than out.

The insurance industry offers valuable pricing signals in those areas – like a canary in a coal mine, says Mr. Gordon. “Those nicer homes and the inflation and climate change are making it more expensive to live in environmentally sensitive areas,” he says. “You have to realize that, as people decide where they want to live, the costs and the risks in that are part of those considerations.”

What happens when homeowners lose coverage?

Those homeowners still have access to insurance. Their first step is to shop the remaining companies for a new policy. For consumers who are unable to find or afford a policy, each state offers its own version of a FAIR plan – Fair Access to Insurance Requirements. Some states run those plans themselves; others outsource the plans to private insurers.

FAIR plans have been around since 1968 and offer policies of last resort. They are generally more expensive than regular insurance policies, and coverage tends to target catastrophic events.

Reducing risks before catastrophe strikes helps everyone. Communities can take steps to reduce harm from storms by investing in infrastructure to manage floodwaters or drought. And individuals can do things like home-hardening – using fire-resistant building materials – and clearing flammable debris to drastically reduce fire risks.

About 66% of American households own their home – and 88% of homeowners carry insurance. For those 12% who either can’t afford or choose not to insure their home, fallout can be substantial. “If we can’t insure our home, then we can’t sell our home. It ripples into the real estate market. It ripples into the tourism market,” says Ms. Balber. “So the consequences of that are serious.”

Last year, California became the first state to require insurers to offer discounts to homeowners who make their properties safer from wildfires.

An insurance crisis is avoidable, says Ms. Balber. “We all know that another fire is going to hit, but that’s what the industry is here for. And we need to be investing in the meantime in reducing the risk so we don’t reach the breaking point.”

Teens fight for say in school book choices

Book challenges at U.S. schools are often dominated by adults. But teens are amicably inching their way into the discussion, with the goal of amplifying student perspective.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As public debate around banning books in schools has increased, so has youth activism – drawing students to school board meetings and peaceful protests.

For the young people, it has been less about entering the culture war fray and more about magnifying student perspective.

School book bans increased 28% during the first semester of the 2022-23 academic year compared with the prior six months, according to an analysis by PEN America. Many of the challenged titles are written by or about people of color or those within the LGBTQ+ community, or address race, racism, gender, or sexuality.

“These are the books that are in our schools and our libraries,” says Thomasina Brown, a senior at Nixa High School in Missouri and a member of Nixa Students Against Book Restrictions. “And we felt that we weren’t being heard.”

The school board there voted in June to remove three books and restrict two more by requiring parental permission. The board also decided to retain without restrictions “Maus” by Art Spiegelman, for example.

When board members explained why they voted a certain way, they cited some of the points made by students. Thomasina considers that progress.

“It took a while for that to actually happen,” she says, “but it felt like a step in the right direction.”

Teens fight for say in school book choices

Deliliah Neff knows Nixa, the southwestern Missouri city where she is growing up, has some cultural limitations.

Located in Christian County, the city has roughly 24,000 residents, who are overwhelmingly white. So the 17-year-old has turned to literature to fill in those gaps. But a book she is currently reading – “All Boys Aren’t Blue,” a series of personal essays about race and LGBTQ+ issues by George M. Johnson – no longer lives on the shelves of her high school library. She received it as a Christmas gift.

“Hearing about these stories from authors of color, it’s really important for me, especially because when I go to college, I want to leave Nixa and venture out,” she says.

The Nixa School Board voted to remove it last year. Since then, other books have been pulled or restricted, but not without pushback from the community’s teenage readers. Nixa Students Against Book Restrictions (SABR), a grassroots-style group, has rallied to keep its school library’s collection intact.

Fueled largely by parental demands and new state legislation, school book bans increased 28% during the first semester of the 2022-23 academic year compared with the prior six months, according to an analysis by PEN America, a group promoting free expression. Many of the challenged titles are written by or about people of color or those within the LGBTQ+ community, or address race, racism, gender, or sexuality.

In response, California lawmakers are considering a bill that would require a two-thirds majority vote from a school board or governing body before banning any instructional materials, textbooks, or curriculum.

The situation has inspired the latest iteration of youth activism, drawing students to school board meetings and peaceful protests, where they have advocated for their right to read a diverse set of books. They’re offering a counternarrative to discussions that, in many places, have featured hostile exchanges between adults against the backdrop of broader culture wars.

For them, it has been less about entering the fray and more about amplifying student perspective.

“These are the books that are in our schools and our libraries,” says Thomasina Brown, a senior at Nixa High School and member of Nixa SABR. “And we felt that we weren’t being heard.”

“A step in the right direction”

Upperclassmen started the group when book challenges made their way to Nixa during the 2021-22 school year, and now, students including Deliliah and Thomasina are carrying it forward. The group leaders regularly post on an Instagram account, letting fellow students know about upcoming board meetings, school board elections, and ways to address book bans. Among the recommendations: creating free little libraries, forming book clubs, and, of course, attending board meetings.

The movement is entirely student-led, in part because they’re hesitant to ask a teacher to serve as an adviser.

“We don’t want to put them in a position where they have to tell us no, even if they do agree with us,” Thomasina, who is 16, says.

Last year, Missouri legislators passed a law that includes an amendment putting school librarians and educators at risk of criminal prosecution if they provide “explicit sexual material” to a student. Nixa’s school board president, Joshua Roberts, says staff members flagged several books for evaluation because of the new state law. The other book challenges came from parents or community members.

Despite the students’ efforts, the school board in June voted to remove three books (“Blankets” by Craig Thompson; “Something Happened in Our Town” by Marianne Celano, Marietta Collins, and Ann Hazzard; and a graphic novel adaptation of “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood) and restrict two more by requiring parental permission (“Lucky” by Alice Sebold and “Empire of Storms” by Sarah Maas).

A parent who spoke at the June meeting in support of removing certain books said they “contain obscene, sexually explicit content or provoke racial division,” according to a report from the Springfield News-Leader.

The board also decided to retain “Maus,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel by Art Spiegelman, without restrictions. It did the same for “Unpregnant” by Jenni Hendriks and Ted Caplan after board members could not reach a majority vote in June and again in July.

When board members explained why they voted a certain way, they cited some of the points made by students. Thomasina considered that progress and a sign of more civil dialogue.

“It took a while for that to actually happen, but it felt like a step in the right direction,” she says. “We aren’t being completely seen or maybe understood, but at least we’re being heard to some extent.”

Preserving a path to empathy

The Panther Anti-Racist Union (PARU), a student group at Central York High School in Pennsylvania, persuaded its school board to go a step further: The board overturned a ban on several books in the school library and created a new policy, which allows parents to bar their own children from reading certain books without revoking them for the entire student body.

It was the second time the board has reversed course on such a decision. About two years earlier, also under pressure from students, the board undid a ban on resource materials about diversity and racial justice that staff members had gathered following the murder of George Floyd.

Mandy Wang, who is 17 and a PARU member, says students rallied outside the high school for weeks and also attended school board meetings. A concern for future generations fueled her motivation: She wants to ensure that her 6-year-old brother can continue reading books by diverse authors and learn about other communities and cultures as a result.

“With reading,” she says, “you become better at showing empathy and being able to empathize.”

Fellow PARU member, 15-year-old Brezlyn Koller, considers the policy change a fair compromise because it doesn’t take away other students’ rights to read a book. One of her favorite novels, “Push” by Sapphire, tells the story of a 16-year-old girl who has been abused and sexually assaulted. Brezlyn understands the subject matter may not be easy for others to digest.

“It’s a hard story to read, and it’s not for everyone,” she says. “But that doesn’t mean you can just take it out of a library.”

Ben Hodge and Patricia A. Jackson, who teach at Central York High School and serve as faculty advisers for PARU, credit their students with setting and controlling the narrative, dispelling misinformation along the way. Their advice to students: Keep at it.

“I’m always saying to the kids that it’s good to be vigilant in the turbulent times,” Ms. Jackson says. “But you have to be equally as vigilant in the quiet times.”

Throughout the history of the United States, youth activism has injected energy, exuberance, and optimism into social movements, which have helped sustain and keep them going, says Matthew Diemer, a professor of education and psychology at the University of Michigan. He sees opportunities for students to band together and form coalitions around their shared interests.

“I think it’s important to be active at the local level, but perhaps that can coalesce into something more regional or national,” he says.

Students at every board meeting

Back in Nixa, the school board wants students to be a permanent fixture at every board meeting going forward, says Mr. Roberts, the elected body’s president. This school year, a student representative from the high school – chosen without input from the board – will have dedicated speaking time at each meeting. Students can also continue to speak during the public comment periods.

Mr. Roberts says the students, unlike some adults who engaged in name-calling and other unruly behavior, brought a calming, mature presence to the discussions.

“There was zero hostility that came out of the students,” he says. “They were perfect. They always have been.”

Deliliah expects additional book challenges this school year, so she’s gearing up for more activism. Until then, she is focused on finishing “All Boys Aren’t Blue.”

“I think it’s a really good book,” she says, “and there are a lot of life lessons in there.”

Points of Progress

Solar panels get a boost, and a green container ship sails

In our progress roundup, solar energy lessens demand on a grid, allowing the third-largest power plant in New England to be safely retired.

Solar panels get a boost, and a green container ship sails

1. United States

Rooftop solar panels are helping shore up New England’s power grid even during the winter. Officials say that rooftop solar – long thought to be a small and unreliable source of energy – reduces demand and that one of the region’s largest carbon emitters, Mystic Generating Station, can be retired next May without risking the reliability of the grid.

“Peaker” plants like Mystic are used during high demand to prevent blackouts. In winter, when natural gas demand is high for heating, many peaker plants burn oil instead.

The Electric Power Research Institute and ISO New England, the grid operator for six states, found that behind-the-meter photovoltaics contribute significant amounts of energy even when operating at low capacity. The study estimated that every 700 megawatts of solar capacity reduces oil use by 7 million to 10 million gallons, or gas use by 1 billion to 1.5 billion cubic feet. The region currently has 5,400 megawatts of solar capacity, mostly on rooftops.

Researchers stressed that grid reliability is still a concern and that improved weather forecasting is needed. Mystic will be brought offline as the country’s first major offshore wind farm, Vineyard Wind, comes online near Massachusetts.

Source: E&E News

2. Denmark

The first cargo ship powered by green methanol is making its maiden voyage, sailing from Seoul, South Korea, to Copenhagen, Denmark. Danish company Maersk, one of the world’s largest shipping companies, ordered the ship two years ago after committing to only purchasing ships that can run on green fuels.

The ship’s biomethanol is a low-carbon fuel produced from landfill gas that can cut a ship’s carbon emissions by 60% to 75%. (Green methanol is also made from captured carbon dioxide and hydrogen from renewable electricity.) Diesel fuels used in shipping are responsible for particulate pollution and roughly 1 billion metric tons of CO2 every year – about 3% of global emissions and growing.

Investments in port infrastructure and scaled-up production of green methanol are needed for the fuel to be a widely used interim solution toward net-zero goals. Five other major shipping carriers are purchasing green methanol ships, with 120 ships total in the works.

Sources: Fast Company, Canary Media, Safety4Sea

3. Colombia

Colombia slowed deforestation by 29% across the country last year, its best result in a decade. Officials say that what amounts to 50,000 spared hectares (193 square miles) is the result of a historic effort to put the protection of Colombia’s natural resources – especially the Amazon – at the forefront of negotiations with armed groups, which still exert control in some rural areas.

Deforestation by cattle ranching, logging, mining, and farming soared in Colombia after a 2016 treaty disbanded the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), which had limited logging, partly to ensure their cover against government air raids. Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro, is trying to fulfill a 2022 promise of “total peace,” and one rebel faction, Estado Mayor Central, ordered farmers to stop cutting down trees as a “gesture of peace” toward the government. Some doubt that all armed groups will follow suit, but other observers say the rebels’ move signals growing appreciation for the environment.

President Petro’s administration also attributed the reduction in deforestation to investigating illegal activities and working more closely with local communities to pay them for maintaining forests.

Sources: The Guardian, Reuters

4. Nigeria

An organization of engaged citizens is monitoring Nigeria’s public sector to combat corruption. Since 2014, Tracka has used open data research to encourage citizen participation in government processes.

Experts say that Nigeria’s widespread corruption stems from the lack of accountability and transparency that enable fraud. In 2021, Nigeria’s anti-graft agency recovered 152 billion Nigerian naira ($386 million) in stolen funds earmarked for rural development.

Tracka visits rural communities to document progress on government development projects, training people to participate in budgetary processes and compiling publicly available information that can be used to pressure officials to take action. In 2018, failure to upgrade a health facility in northwest Sokoto state had left patients being cared for outdoors under trees, despite a federal government allocation of 34 million naira ($86,300) for the project. The state renovated the facility after attention was called to the problem by Tracka’s local social media campaign.

Tracka has faced some difficulty gaining community members’ trust, as some view the group as unfairly persecuting elected officials. Safety concerns also prohibit representatives from traveling to some parts of the country. But the organization has successfully reached 967 communities – improving the lives of over 1 million people.

Source: Social Voices

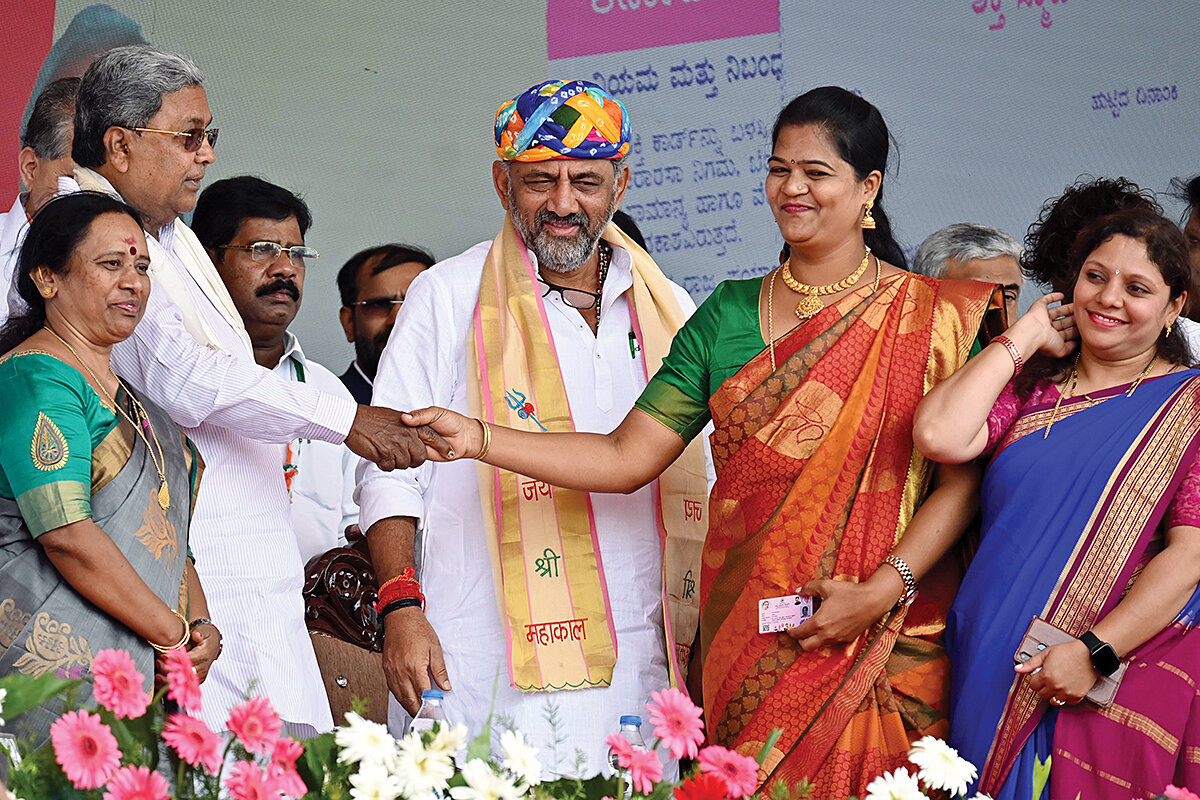

5. India

The Indian state of Karnataka is providing free travel for women and transgender people on state-run buses. The initiative aims to boost women’s mobility and participation in the workforce, which hovers at 23%.

State-run buses saw daily ridership by women increase from 4.18 million to 5.57 million during the program’s first month. Half of the bus seats remain reserved for men.

Many Indian women are dissuaded from traveling because they must ask male family members for money to pay fares. “In India, women’s mobility has always been restricted as a cultural practice,” said Tara Krishnaswamy, whose nonprofit works to elect more women in India. “Even today, in many parts of the country, a woman’s ability to travel alone is in question.”

While skeptics say the initiative will hurt the state’s economy, free buses were a campaign promise made before the May elections by the winning Congress party. The nation’s capital and at least two other states run free bus programs for women, but Karnataka’s is likely the largest.

Sources: The Guardian, India Today, The Quint, Deccan Herald, The Indian Express

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Chile’s light of truth on a dark past

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Chile reached a turning point Wednesday in its long quest to seek healing after a massive injustice. President Gabriel Boric formally launched the country’s first plan to find the remains of more than 1,000 people who went missing during the 1973-1990 military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

In the more than three decades since the restoration of democracy, the remains of only 307 of the disappeared have been recovered, leaving many families alone to find the truth of what happened to their loved ones. Chile’s new approach acknowledges the state’s responsibility in dismantling the lies that have insulated the perpetrators of those abuses from accountability.

“The state has to be responsible for finding the truth,” Mr. Boric said in signing a decree formalizing the plan. “This is not a favor to the families. It is a duty to society as a whole to deliver the answers the country deserves and needs.”

This first attempt by Chile to recover lost loved ones marks a start for the families and all of society to combine the truth about the disappeared with, perhaps, forgiveness. A national healing has begun.

Chile’s light of truth on a dark past

Chile reached a turning point Wednesday in its long quest to seek healing after a massive injustice. President Gabriel Boric formally launched the country’s first plan to find the remains of more than 1,000 people who went missing during the 1973-1990 military dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet.

In the more than three decades since the restoration of democracy, the remains of only 307 of the disappeared have been recovered, leaving many families alone to find the truth of what happened to their loved ones. Chile’s new approach acknowledges the state’s responsibility in dismantling the lies that have insulated the perpetrators of those abuses from accountability.

“The state has to be responsible for finding the truth,” Mr. Boric said in signing a decree formalizing the plan. “This is not a favor to the families. It is a duty to society as a whole to deliver the answers the country deserves and needs.”

In the past half-century, as many as 70 countries emerging from conflict or violent authoritarian regimes have created commissions or other models to promote justice by seeking transparency about past atrocities. Those experiments have entrenched the idea of truth-telling as vital in restoring society. South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, for example, offered perpetrators of politically motivated crimes during the apartheid era amnesty for full disclosure. Yet no prosecutions ever followed for those who failed to come forward.

Soon after Chile restored its democracy, the government did set up the world’s first truth commission to probe the Pinochet era and seek national reconciliation. The commission panel’s report and subsequent government audits ultimately estimated that roughly 40,000 people had suffered state violence, including those who disappeared or are known to have been killed by security forces. Despite such findings, the government at the time declined to pursue criminal actions against those implicated. That decision reinforced a culture of impunity in the police and military forces, first set out in a 1978 law during the Pinochet dictatorship that gave soldiers and officials blanket amnesty.

In the past decade, a few private lawsuits have chipped away at that impunity. Families “have put the objectivity of their suffering at the service of the fight for truth and justice, the only way – I believe – to truly rebuild a country and provide the best for its people,” said Almudena Bernabeu, a Chilean human rights lawyer, in an address at the University of California, Berkeley in 2016. “The challenge for all societies, including that of Chile, is to not desire or perpetuate a power that is based on lies, but to dare to build an inclusive society that can overcome them.”

This first attempt by Chile to recover lost loved ones marks a start for the families and all of society to combine the truth about the disappeared with, perhaps, forgiveness. A national healing has begun.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Caregiving? You have what it takes.

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Eric Nager

When caring for someone who is struggling with an injury or disease, endeavoring to see them as God knows them can make all the difference in their recovery.

Caregiving? You have what it takes.

A little over two years ago, I was called to the home of my brother, who was suffering from severe abdominal pain and other symptoms and was in immediate need of assistance. He is a Christian Scientist, as I am, and relies on prayer for healing. He had already called a Christian Science practitioner to pray for him.

As I left my office, I called the practitioner and let him know I was on the way to my brother’s house. The practitioner said that he was knowing about my brother what God knew about him as His unblemished, whole child. I resolved to see him that way myself.

I thought about the qualities that the book “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” identifies as necessary for a nurse – not just a trained nurse but anyone who might be called on to provide care for a friend or loved one. It explains, “The nurse should be cheerful, orderly, punctual, patient, full of faith, – receptive to Truth and Love” (Mary Baker Eddy, p. 395). In Christian Science, Truth and Love are synonyms for God.

It occurred to me that everyone includes these nursing qualities because they are qualities of God, and all of God’s children fully reflect Him. Moreover, when we are receptive to divine Truth and Love and are listening to God’s thoughts rather than to what the physical senses suggest about the problem, we can’t help but be calm, loving, and free of fear.

Understanding our inseparable relation to God, Christ Jesus was able to maintain a mental atmosphere free of fear and doubt when healing individuals. When he was called to the house of one of the religious leaders of his day to heal the man’s sick daughter, the people around her were weeping and wailing because the young girl had just died (see Luke 8:41, 42, 49-55). But Jesus was unimpressed by the material evidence of illness and death and sent the mourners out of the house. Through his trust in God’s power and ability, the girl was revived.

It was this spiritually trusting atmosphere that I wanted to bring to my brother’s situation, knowing that it was most conducive to healing. When I arrived at his house, he expressed concern that he was at a crisis point. I assured him that I was there to help and took all the practical steps I could to make him as comfortable as possible. But just as important, I endeavored to put out of thought any suggestion that my brother was less than the perfect, painless likeness of God.

The Christian Science textbook teaches how to prayerfully banish from thought the suggestions of the physical senses. Mrs. Eddy writes, “When the illusion of sickness or sin tempts you, cling steadfastly to God and His idea. Allow nothing but His likeness to abide in your thought. Let neither fear nor doubt overshadow your clear sense and calm trust, that the recognition of life harmonious – as Life eternally is – can destroy any painful sense of, or belief in, that which Life is not” (Science and Health, p. 495). I strove to be steadfast in recognizing my brother as wholly spiritual, made in the image and likeness of God, who is divine Spirit.

After making sure my brother had everything he needed, I stepped outside. At that moment, I had a very clear sense that all was well with my brother. I had refused to give fear a foothold in my thinking, and that helped purify the mental environment. I quietly rejoiced and gave thanks to God before returning to the house.

As I entered, my brother informed me that the pain and fear had subsided. We acknowledged God’s power together.

My brother slept well that night, and he made steady progress over the next several days. In fact, he was completely free of pain and eating normally by the end of the week. He said this was one of the most significant healings in his life.

The experience was a good lesson for me to trust that when we are called on to aid another, we have God’s help and can do whatever is needed fearlessly and with the expectation of healing.

In whatever capacity we are caregiving, to the degree that we are “cheerful, orderly, punctual, patient, full of faith, – receptive to Truth and Love,” we are expressing the nursing qualities that are so needed in the world and contributing to the comfort and healing of humanity.

Adapted from an article published in the July 17, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Spike!

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when we look at Florida’s less-populated “nature coast,” which bore the brunt of Hurricane Idalia. We’ll explore the outlook for post-storm recovery in the region, including the fishing village of Cedar Key. The barrier island with an “Old Florida” identity has been seeking nature-based solutions to sea-level rise.