- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Taylor Swift off-tone? Definitely not.

Saturday morning marked one week since Hamas terrorized a music festival in Israel at the Gaza border, massacring 260 concertgoers and sparking the Israel-Hamas war. Thousands of miles away from it in Toronto, I woke up struggling to wrap my head around the moment – less than two years after the jolting start to the Ukraine war.

It can be hard to parent at these times – to strike that balance between awareness and innocence. Then my tween asked, “Can we see the Taylor Swift movie?”

Honestly, it was the last thing I wanted to do. I’m only marginally familiar with her music, and the prospect of the glam and glitz of “The Eras Tour” felt off-tone.

I also recognized it would do us both good to get out.

I won’t speak of the music or the movie (just to say that the world now has one more “Swiftie”). I want to focus on the joy. The movie theater became a concert hall, where popcorn was put aside and the audience members jumped out of their seats, dancing with each song and clapping at the end. There was whooping and hollering after a particularly powerfully belted number, as if the audience were watching the performance live in real time.

It’s not that the world around me could be forgotten. It wasn’t lost on me that 260 concertgoers were killed in this very same way: reveling in music. And thousands of innocent people on both sides face the revenge of war.

But then I watched my daughter jump up and run to the front of the theater with other young people. I pushed away that darkness clouding over me – and allowed her ebullience to light our Saturday evening.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Gazans navigate dire shortages as war rages

Before the war, Gaza was already overcrowded, and power, water, and food were in chronic short supply. Now, with Gazans under siege and displaced in search of safety, a humanitarian crisis is intensifying.

-

By Ghada Abdulfattah Special contributor

-

Hind Khoudary Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

A flood of refugees has inundated the southern Gaza Strip following an Israeli warning to vacate the combat zone around Gaza City. Abla Musabh’s family reached Al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah after a seven-hour trek southwestward from Gaza City on foot and on empty stomachs, their third displacement in a week.

They, like many, now sleep outside the hospital, believing it will be spared missile strikes and fighting. “It’s cold at night,” she says. “For the past week we have been sleeping on cardboard boxes. There is nothing here.”

Food, shelters, medical supplies, and clean water all are in short supply. The international community pledged to get aid into the besieged strip, but at the Egyptian border, hundreds of metric tons of aid remained in trucks, awaiting a safe corridor to enter. As of Monday evening, the crossing remained closed, despite intense U.S. diplomacy led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Mohammed and his family, who evacuated their home in east Khan Yunis moments before a missile strike destroyed it last week, now live in a furniture shop-turned-shelter with four other families, a total of 29 people including 14 children sharing one room.

“Despite the difficult circumstances, I consider myself fortunate to have found any shelter at all,” he says.

Gazans navigate dire shortages as war rages

As the international community pledged to get humanitarian aid into the besieged Gaza Strip Monday, the enclave’s lone border crossing with Egypt remained closed, Israeli missile strikes continued, and Gazans reported a “dire situation.”

There's minimal food, overflowing makeshift shelters, no medical supplies, and little access to clean water.

“There’s no bread, no food; my children haven’t eaten today,” says Abla Musabh, 67, whose family reached Al-Aqsa Hospital in Deir al-Balah late Sunday after a seven-hour, 10-mile trek southwestward from Gaza City on foot and on empty stomachs. It was their third displacement in a week.

They, like many, now sleep outside the hospital, believing it will be spared missile strikes and fighting.

“It’s cold at night,” she says. “For the past week we have been sleeping on cardboard boxes. There is nothing here.”

The flood of Palestinian refugees from northern Gaza inundated the southern part of the strip following an Israeli warning to some 1.1 million people to leave the combat zone around Gaza City, the focus of an anticipated Israeli ground offensive against Gaza’s rulers, Hamas.

Israeli shelling and airstrikes have killed 2,750 Palestinians, including 1,000 children, and wounded 9,700, the Gaza Health Ministry said, after marauding Hamas militants killed more than 1,400 people in southern Israel, most of them civilians. Late Monday, Hamas fired more rockets toward Tel Aviv and Jerusalem.

In southern Gaza, where the United Nations says more than 600,000 Gazans have relocated in less than 72 hours following Israeli instructions and amid intensified bombing, evacuees and local communities are straining to make ends meet. Supplies are dwindling in what the U.N. describes as “increasingly dire conditions.”

Backup at border

Meanwhile, hundreds of metric tons of aid, food, and medicines remained in trucks lined up at the Egyptian border town of Arish near the Rafah crossing, awaiting an Israeli-Hamas cease-fire, a political agreement between Egypt and Israel, and a safe corridor to enter.

As of Monday evening, a deal had not been struck and Rafah remained closed, despite intense U.S. diplomacy led by Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Egypt and Israel failed to reach an agreement over the search of the convoys entering Rafah and their safety, while the lack of a cease-fire made the entry and distribution of aid impossible, according to the U.N.

“We literally have nothing to eat. The shelves in the shops are all empty; there are no diapers, food, or even snacks. Clean drinking water is nonexistent,” says Mohammed, who evacuated with his family from their home in east Khan Yunis moments before a missile strike destroyed it last week. “I have to tell my children to ration the little food we have left.”

He, his wife, and three children now live in a furniture shop-turned-shelter with four other families, a total of 29 people including 14 children sharing one room.

“Despite the difficult circumstances, I consider myself fortunate to have found any shelter at all,” says Mohammed, whose parents and extended family have sought shelter in the hallways of overfull United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) schools.

Fortunate families who do find food are subsisting on canned beans, processed cheese, and, if they are fortunate and risk waiting in line for hours, bread.

Milk and infant formula have disappeared from the shelves of the corner stores that have survived the airstrikes. Pharmacies report having run out of medical supplies.

With most shops now bare, Gaza City resident Bahaa Bahhour, like many Gazans, races from shop to shop amid bombings looking for canned beans and cartons of milk.

“I find myself moving from one supermarket to another under the buzzing of Israeli drones hovering overhead,” Mr. Bahhour says. “When I finally find food items, the prices are exorbitant.”

“If we do not succumb to airstrikes, we will succumb to hunger,” Mr. Bahhour warns.

Apartments overflow

Apartments in southern Gaza that only two days ago were hosting two evacuee families are now housing dozens as the migration of displaced families from northern Gaza continues, with many families spilling out of apartment buildings and staying in makeshift tents, exposed to the elements.

More than 1 million Gazans have left their homes, and within the last 24 hours a quarter of a million have sought refuge at UNRWA schools, where the U.N. agency said “clean water has actually run out.”

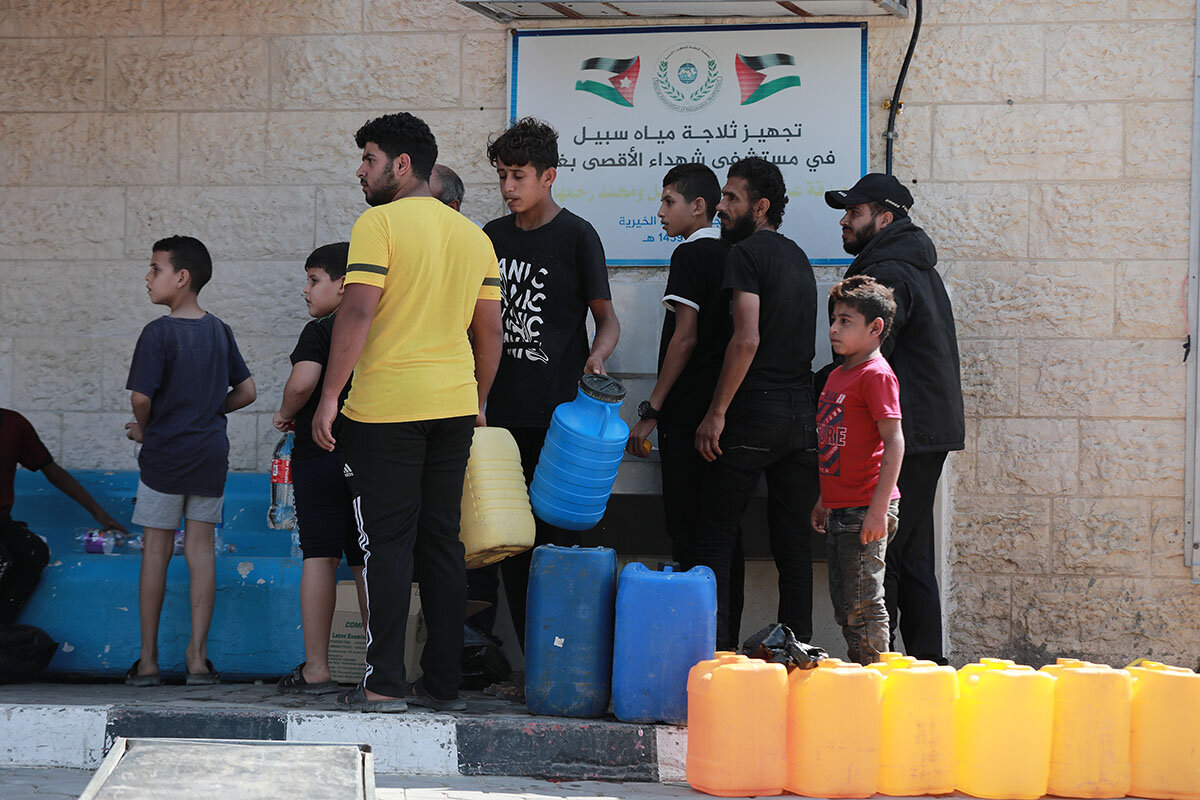

Amid Israeli pledges to resume water services to the south, Gazans and the U.N. report water flowing only in parts of Khan Yunis, leaving the vast majority of 2.2 million Gazans still without access.

Since being displaced from their home in Gaza City to a makeshift shelter in an UNRWA-run school in Khan Yunis, Mohammed Mady and his family have been relying on a public water spring normally reserved for those who are disadvantaged and livestock.

“We are currently relying on the generosity of others,” Mr. Mady says. “I could have never imagined this. But if God will grant us life, my first act will be to build a public water well. I cannot even fathom a situation in which people are denied water.”

The few food items left in Gaza have skyrocketed in price.

A 6.6-pound bag of bread used to cost 8 shekels ($2), enough to feed a family of 10 for the day. The few bakeries still churning out bread are now selling 4.4 pounds of bread for the same price. Families are trying to make a pita loaf last longer and feed more than one family member.

It is both a humanitarian and economic crisis for the besieged coastal enclave, where prior to the war 50% of people were unemployed and 53% were below the international poverty line, according to the World Bank.

At the Kholy bakery on once-bustling Al Nasser Street in Gaza City, customers wait from six to 10 hours for a chance at bread, standing outside exposed to a potential missile strike. The line becomes so long that most customers take a number, return to their shelter, and wait for hours to check in to see if it’s their turn.

The smell of freshly baked bread briefly covers the scent of dust and rubble, but despite hunger setting in, few have an appetite.

“We have no stomach for eating,” one customer says while waiting for his turn, “but I have seven children and evacuees in my house who I must feed.”

The topic while waiting

The conversation in the bread line is, inevitably, of death.

“Did you hear about the family who was killed today?”

“A whole family was killed?”

“I feel like if I evacuate I will lose everything.”

“What will happen to us?”

“My relative was killed. They did not find his body.”

Other bread-seekers were not so fortunate. The cashier at Al Baladi Bakery in Deir al-Balah, after running out of flour midday, announced to customers, “I am sorry, no more bread today.”

Yet communities are also pitching in. Slightly better-off Gazans are donating bags of rice and scraps of wood to encampments at UNRWA schools so that evacuees can cook plain rice on campfires and feed dozens.

With the electricity cut, and with very few Gazans having fuel left for private generators, the entire strip goes dark at night. The only source of electricity for Gazans is at hospitals. Thousands rely on them to charge their phones and, if they have contacts, access a rare Wi-Fi hot spot.

Yet with less than 24 hours of reserves, fuel and electricity at all hospitals across Gaza were expected to run out as of Tuesday morning, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs warned early Monday.

Four hospitals in northern Gaza had ceased operation as of this writing, while 21 others have been ordered to evacuate, even as they struggle to maintain services to thousands of wounded people.

The number of wounded Gazans far exceeds the number of beds in hospitals, with most new patients lying on hospital floors. Dr. Khalil Degran, a surgeon at Deir al-Balah’s Al-Aqsa Hospital, describes the surgery department as “a catastrophe.”

“Al-Aqsa Hospital is witnessing a crisis in medical supplies,” he says.

In a statement posted on social media early Monday, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres noted that “the U.N. has stocks available of food, water, medical supplies and fuel in Egypt, Jordan, the West Bank, and Israel.

“They can be dispatched within hours,” he said. “To ensure safety, our staff need to be able to bring these supplies into and throughout Gaza safely, and without impediment.”

Israel’s moral challenge in Gaza – to fight humanely

Israel has pledged to destroy Hamas in the densely populated Gaza Strip. Can it do so without violating the laws of war?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As if the military difficulties of Israel’s war to destroy Hamas were not daunting enough, the tens of thousands of Israeli soldiers massed around the Gaza Strip are facing another, but equally formidable challenge – a moral one.

How do they wage a ground war against Hamas without inflicting a humanitarian catastrophe on the 2.2 million Palestinian civilians living in one of the most densely populated territories on Earth?

Military logic dictates that Israel wants as few civilians as possible in the way of its expected street-to-street, house-to-house, tunnel-to-tunnel ground assault on Hamas.

Hamas’ political logic demands that it divert the world’s attention from its barbarous attack on Israeli civilians 10 days ago, killing 1,400 of them, and instead focus international concern on the Palestinian civilians now suffering in Gaza.

Rather than seeking to balance the military and humanitarian, the Israeli government’s initial emphasis seemed to be on punishment by overwhelming force. It launched an unprecedented missile, bombing, and artillery assault on Gaza that has so far killed 2,750 civilians, and imposed a total blockade on the Gaza Strip, holding back food, water, fuel, and electricity.

Over the weekend, Israel softened some of its measures. But the military’s fundamental dilemma remains: how to dislodge Hamas fighters from Gaza without violating the rules of war.

Israel’s moral challenge in Gaza – to fight humanely

As if the military difficulties of Israel’s war to destroy Hamas were not daunting enough, the tens of thousands of Israeli soldiers massed around the Gaza Strip are facing another, but equally formidable challenge – a moral one.

How do they wage a ground war against Hamas without inflicting a humanitarian catastrophe on the 2.2 million Palestinian civilians living in one of the most densely populated territories on Earth?

Resolving that dilemma was always going to be difficult.

Military logic dictates that Israel wants as few civilians as possible in the way of its expected street-to-street, house-to-house, tunnel-to-tunnel ground assault on Hamas.

Hamas’ political logic demands that it divert the world’s attention from its barbarous attack on Israeli civilians 10 days ago, killing 1,400 of them, and instead focus international concern on the Palestinian civilians now suffering in Gaza.

That is already happening. On his diplomatic shuttle around the Middle East last week, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken found Washington’s Arab allies unwilling to condemn the Hamas attack, pressing instead for humanitarian aid to Gaza and restraint by Israel.

Mr. Blinken had been due to fly back to Washington over the weekend, but added a second visit to Israel, in the evident hope of arriving at a shared response to a conundrum that President Joe Biden has framed starkly.

In his first, impassioned response to the Hamas attack, Mr. Biden called it “pure, unadulterated evil.” But in a social media post Sunday, he pointed out that “the overwhelming majority of Palestinians had nothing to do with Hamas’ appalling attacks and are suffering as a result of them.”

Mr. Biden has also urged Israel to follow “the laws of war.”

United in shock

As Mr. Blinken arrived in Israel on Monday, it was clear the Israeli authorities were still seeking a way to balance military and humanitarian imperatives – and in fact were being guided more by political calculations.

Since the Hamas attack – the worst such assault, abuse, abduction, and murder of Jews on a single day since the Holocaust – Israelis of all political persuasions have been united in a sense of shock, vulnerability, mourning, and anger.

Far from an effort to balance the military and humanitarian, the government’s initial emphasis seemed to be on punishment by overwhelming force, launching an unprecedented missile, bombing, and artillery assault on Gaza that has killed 2,750 civilians, according to local authorities, and wounded nearly 9,700.

Israel imposed a siege on Gaza as well, cutting off all supplies of food, water, fuel, and electricity – a violation of international law, as the United Nations, Arab states, aid agencies, and even Israeli allies in Europe reminded the government.

But there have also been signs Israel is not impervious to such reminders of the need to address the plight of civilians as it has ramped up military operations against Hamas.

The siege announcement was followed by a slightly more nuanced policy: it would be lifted, Israel said, if Hamas freed the nearly 200 hostages it is holding. On Monday, Israel said it would resume water supplies to southern Gaza, according to U.S. officials. And in some cases, the Israelis have also been following their traditional policy of giving advance warning to residents of areas targeted by airstrikes.

And last Friday, Israeli planes dropped leaflets in the northern half of Gaza, where most of Hamas’ weaponry and fighters are based, telling its roughly 1 million civilians to move south for their safety.

For Hamas, which issued a counter-order for them to stay put, this was mere “psychological warfare.” For aid agencies, a hasty evacuation was impossible, and a flood of displaced people was bound to worsen shortages of basic necessities in Gaza’s south, as has proved to be the case.

While that remains a real concern, Israel’s initial 24-hour evacuation “window” remained open – and the widely expected ground invasion still on hold – through the weekend.

A sense of humanity

The question now is whether aid supplies, waiting on the Egyptian side of the Gaza border in Sinai, will be allowed into Gaza – and whether a broader humanitarian corridor can be established.

Still, even if that happens, the core problem of balancing Israeli retaliation with the sparing of civilian suffering is not going to go away.

Some civilian casualties are unavoidable in war, especially during a bombing campaign as intensive as the one Israel has been waging in recent days. And, as a powerful New York Times essay by a U.S. military veteran lays out, avoiding such casualties in a full-scale ground offensive is likely to present an even tougher challenge.

On top of the moral imperative to do all they can to minimize such suffering, though, Israel’s leaders have a political spur to do so as well. They know that as the civilian costs mount, the broad international sympathy Israel received after the Hamas terror atrocity is bound to erode.

Additionally, the longer the Israel-Hamas war goes on, and the higher the civilian casualties, the more strongly Iran’s surrogate army, Hezbollah, may be tempted to attack from its bases in Lebanon, to Israel’s north.

There may also be another reason for Israel to try to keep the Gaza war laser-focused on Hamas itself.

It’s Israelis. After last Saturday’s Hamas attack, relatives of a number of the hostages taken into Gaza said that, in their determination to hold on to hope, they were relying on a simple, shared sense of “humanity” with the hostage-holders.

Whether that mood spreads as the Israel-Hamas fighting intensifies will depend on something that may prove especially difficult for many Israelis, still traumatized by the terror rampage.

It will be their ability and readiness to keep two kinds of images in their minds simultaneously, not with a sense of equivalence, but with an equal human value: the horrifying memory of fellow Israelis abducted, raped, and murdered by Hamas terrorists last Saturday, and the terrified faces of Palestinian civilians fleeing Israeli bombs.

How remote Darién Gap became key route for migrants

Record migration through the treacherous Darién Gap is a “wake-up call” for governments across the region. But it’s touching local communities in positive – and painful – ways, too.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Manuel Rueda Contributor

The long-isolated village of Bajo Chiquito in eastern Panama, at the edge of the Darién Gap, is the first place hundreds of thousands of thirsty, exhausted migrants encounter as they emerge from the grueling, roadless rainforest that stands between South and Central America.

The community has become a hectic transit point for migrants and refugees from around the world who hope to reach the United States.

Economic, political, and security crises are driving migration north through the Americas in recent years. Visa requirements are forcing a growing number of people to take this dangerous overland route. So far this year, more than 400,000 people have crossed the Darién Gap, a number that overshadows the record of 250,000 people crossing in 2022.

It’s creating a humanitarian crisis in Panama and other countries to the north, as governments struggle to provide health services to migrants or help those who get stranded. And the vast transit here is having effects beyond border crises: In this small stretch of the journey, migration has boosted local economies in long-forgotten and isolated communities, changing the way of life of the Indigenous Embera people, as well as increasing pollution and destruction of the rainforest.

How remote Darién Gap became key route for migrants

The remote Indigenous village of Bajo Chiquito can only be reached through muddy tracts that are impassable when it rains, or by motorboats light enough to navigate the shallow waters of the Turquesa River.

But over the past five years, this isolated community in eastern Panama has become a busy, often hectic transit point for migrants and refugees from around the world hoping to reach the United States.

It’s the first place that thousands of thirsty and exhausted people encounter as they emerge from the grueling Darién Gap, the roadless and mountainous rainforest that stands between South and Central America.

“It was a terrible journey,” says Jessica Tovar, a Venezuelan woman moving in a group of 17 people that included her husband, her two children, and members of their extended family. She describes crossing rivers with deadly currents and passing multiple lifeless bodies during the trek.

Despite its dangers, so far this year, 400,000 people have come through the rainforest on their way to the U.S., according to Panamanian officials. It’s a record that overshadows the 250,000 crossings registered in 2022.

Economic, political, and security crises across Latin America – and the world – have driven migration north through the Americas in recent years. Visa requirements prevent many from flying to countries in Central and North America, forcing a growing number of people who seek protection in the U.S. to take this dangerous overland route. Attempts by the U.S. and Mexico to deter migrants with more restrictive immigration policies have yet to generate change.

It’s creating a humanitarian crisis in Panama and other countries to the north, as governments struggle to provide health services to migrants, or help those who get stranded. And the vast transit of migrants here is having effects beyond border crises: In this small stretch of the journey, migration has boosted local economies in long forgotten and isolated communities, changing the way of life of the Indigenous Embera people, the original inhabitants of the Darién Gap, as well as increasing pollution and destruction of the rainforest.

A “wake-up call”

The Panamanian government has long dealt with migration by implementing a “controlled flow” policy, which enables migrants to cross the country quickly on supervised buses. More recently, Panama has started working to dissuade migrants from crossing the Darién Gap. The border police, SENAFRONT, launched a social media campaign this year called “Darién is a jungle, not a route.” It shows videos of common dangers migrants face, such as falling from steep cliffs or drowning in treacherous rivers.

“The migrants are being fooled by smugglers [in Colombia] who promise them this is an easy two day trek,” says Reiner Serrano, a brigade commander for SENAFRONT. While his agency can’t turn people away at the edge of the rainforest, it is trying to limit the number of routes migrants take, he says. SENAFRONT is also targeting groups that charge migrants to bring them across.

Government data shows 55% of migrants crossing the Darién Gap this year are Venezuelans. For some, it isn’t their first choice, but a decision made after struggling to make ends meet in other South American countries.

Eliana Rivas is from the Venezuelan state of Merida and says she was working as a manicurist in Colombia the past two years, making a little above the nation’s minimum wage of $250 a month. It barely covered food and rent.

“I want to do better than that,” Ms. Rivas says of her motivation to try to reach the U.S.

A report published in September by the International Organization for Migration and its partners in the Americas found that of the 6.4 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees currently living in other Latin American countries, 4.4 million are struggling to access basics including shelter, food, education, and healthcare.

The current situation reflects, in part, the difficulties many migrants have had in integrating or making ends meet in South American countries, says Caitlyn Yates, an expert on immigration at the Strauss Center for International Security and Law, and who lived in villages along the Darién Gap for six months.

“It’s a wake-up call,” she says, “that if you try to focus [solely] on enforcement to reduce the numbers of individuals arriving at the U.S. border [it] does not work.”

South American countries have done a “commendable” job at regularizing Venezuelan migrants in recent years, says Zachary Thomas, one of the report coordinators. But the struggle for Venezuelans to cover their basic needs in places like Peru, Colombia, or Ecuador could continue to drive immigration to countries in North America through the Darién Gap, he says.

“There has been a global cost-of-living crisis that countries in the region have not escaped from,” Mr. Thomas says. “Migrants are sometimes the most vulnerable in these situations, because they lack access to support networks.”

Migrants from Ecuador and Haiti are the second and third biggest nationalities crossing the Darién this year, making up about 22% of those making the trek. The remainder come from dozens of countries that include China, India, Angola, and Afghanistan, which fell to the Taliban two years ago. This year, 2,500 Afghans have crossed the Darién Gap on their way to the U.S., many first flying to Brazil on humanitarian visas.

Opportunity – and damage

In Bajo Chiquito, hundreds of migrants line up each day for several hours under the sun to get transit permits from Panamanian immigration officers.

While they wait, locals wave water bottles and set up stalls on the village’s main streets selling new shoes for migrants whose boots have taken a pounding in the Darién jungle. Others charge phone batteries for $1.50 and sell internet access. It has the feel of a chaotic street market, where many languages are spoken. In September, more than 2,000 people arrived here daily, according to Panamanian officials, most sleeping in tents along the river and under local homes built on stilts.

Just a decade ago, this community of 400 was a quiet village whose economy relied mostly on earnings from small banana farms, says Nelson Aji, an Embera farmer who also serves as the village’s traditional leader.

“Many people are no longer tending to their farms” or hunting, Mr. Aji says. “There is too much business with the migrants.”

Once migrants are able to register with Panamanian officials they take small boats to a government-run camp where they can board buses to the border with Costa Rica.

“We have to make the most of this,” says Elvis Pacheco, who has a fully stocked store selling soft drinks, snacks, menstrual products, and basic medicine. “It’s a good time for those who know how to invest their money.”

But some locals worry about the long-term impact the massive movement of migrants could have on the environment and communities here.

Everyday at least 130 motorboats take people from Bajo Chiquito to the government camp. Boat captain Cono Ortega says that the Embera depend on river water to wash their clothes, cook food, and bathe. Their villages lack pipes and running water and are accumulating trash left by the thousands of people passing through.

The sharp increase in migration is causing “irreversible” damage to the rainforest, Panama’s minister of security said during a recent visit to the Darién Gap. UNICEF has set up water processing plants powered by solar panels in some villages and the camp to increase the supply of safe drinking water.

“This should be an opportunity for the government to take a serious look at how to invest in our communities,” says Leonides Cunampa, the main chief of the Embera Wounan territory.

Seeking alternatives

To encourage migrants to head to the U.S. legally – and avoid routes like the Darién Gap – the U.S. recently opened Safe Mobility Offices in Colombia, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. In Colombia, 30,000 individuals have applied for interviews through the Safe Mobility initiative.

The offices, which are staffed by international organizations, refer qualifying applicants to the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, and put them on an “expedited” track for resettlement, a State Department spokesperson says.

Some 4,000 migrants have been referred so far (1,000 from the Colombia office), with another 4,500 people applying for other permissions or programs that could allow them legal access into the U.S.

Wait times are long, and the program’s website has crashed several times as it struggles to keep up with demand.

That means that for many currently in South America who are seeking immediate safety or want to rebuild their lives in the north, the overland route across the Darién Gap is still their preferred option.

The Biden Administration has promised to swiftly deport those who do not qualify for asylum and issued a five-year ban in May for those who cross into the U.S. illegally. Last week, the administration reached a deal with Venezuela’s troubled government to resume direct deportation flights.

“Only god knows how far we’ll get,” says Ms. Tovar, the Venezuelan migrant. “We just have to have faith and try our best.”

Apologizing for Algerian War: In France, a strained debate

What happened in Algeria was in stark contrast to France’s founding principles of liberty, fraternity, and equality. That paradox, say historians, is at the heart of France’s struggles to come to terms with its colonial past.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Stanislas Hutin never wanted to be a soldier. But when he was called up by the French army to fight in the Algerian War of Independence, he had no choice. For 24 months, Mr. Hutin witnessed death, torture, and violence as the French empire fought to hold power over colonized territory. He kept a journal to cope with the horror.

“When I arrived in Algeria, I saw flagrant injustices. I couldn’t tolerate it,” says Mr. Hutin, now 92.

In 2002, Mr. Hutin published his wartime journal. In 2014, he joined a nonprofit that helped former French soldiers donate their military pensions to aid Algeria. The group, 4AGC, has raised more than €1 million (about $1.06 million) since 2004.

“I didn’t even hesitate one second,” says Mr. Hutin of donating his pension of €800 a year. “We need to recognize the injustices and repair them.”

France, like many countries, has struggled to come to terms with its colonial past. Unlike other European countries, such as Germany, France has notably refused to apologize. In an era when European colonization is increasingly questioned, France and what it owes to the Algerian people show just how difficult it can be to offer amends.

“Our ability to live together in peace means repairing this history,” says historian Christelle Taraud.

In the meantime, individuals like Mr. Hutin are taking matters into their own hands.

Apologizing for Algerian War: In France, a strained debate

Stanislas Hutin never wanted to be a soldier. But when he was called up by the French army to fight in the Algerian War of Independence in 1955, he had no choice. For two years, Mr. Hutin witnessed death, torture, and violence as the French empire fought to hold power over what was, at the time, colonized territory. He kept a journal to cope with the horror.

“Colonization became a somber image of my country,” says Mr. Hutin, who is now 92 and lives in Paris. “When I arrived in Algeria, I saw flagrant injustices. I couldn’t tolerate it.”

In 2002, Mr. Hutin published his wartime journal to share his experiences of a battle he never believed in. But he wanted to mend things further. In 2014, he joined a local nonprofit that helped former French soldiers donate their military pensions to aid projects in Algeria.

Since then, he has been giving his annual €800 (about $844) stipend to 4ACG (Anciens Appelés en Algérie et leurs Amis Contre la Guerre), which goes toward education programs for youth and women in the former French colony. The group, which now counts about 400 members, has raised more than €1 million (about $1.06 million) since 2004.

“I didn’t even hesitate one second. It’s the judicious thing to do,” says Mr. Hutin. “We need to recognize the injustices and repair them.”

France, like many countries including Britain and the Netherlands, has struggled to come to terms with its colonial past. Unlike other European countries, such as Germany, which have agreed to some form of reparations, France has notably refused to apologize – as recently as 2021.

Some people, both Algerian and French, question whether an apology can undo decades of pain and suffering. Others ask, how can France move forward from its colonial past if it can’t even say it’s sorry?

In the meantime, individuals like Mr. Hutin and nonprofits like 4ACG are taking matters into their own hands – offering what recompense they can for what they see as a legacy of injustice.

Today, European colonization, and the harm it wrought, is increasingly questioned. France and what it owes to the Algerian people – monetarily or otherwise – show just how difficult it can be to offer amends amid its tendency to still romanticize its past as a global power.

“We need a new retelling of history that shows the complexity of what happened, is inclusive, and respects both sides of a common story,” says Christelle Taraud, a French historian who specializes in colonization and decolonization. “There’s no question that the place of Algeria, 130 years of colonialization, has an impact on our society today. Our ability to live together in peace means repairing this history.”

France has made some moves to acknowledge the harms it perpetrated in Algeria, whose relationship with Paris was the closest but the most fraught of any of the former colonies. As a presidential candidate in 2017, Emmanuel Macron went further than any French president, calling France’s colonization there “a crime against humanity.” This came after former President François Hollande acknowledged his country’s “unjust and brutal” occupation in 2012.

While the French government has offered some amends to some of its former colonial soldiers and returned stolen artwork as acts of reconciliation, it has struggled to repent or offer sweeping financial reparations to Algeria or other former French colonies.

Meanwhile, conservative voices have hijacked the reparations debate in what critics say is an effort to whitewash colonialism. At the same time, generations of Franco-Algerians are working to reconcile their place in French society, in the face of a continuing national dialogue about immigration and identity.

A colonial legacy

Though the French empire had been present in Africa since the 17th century, its global colonial influence truly began with the conquest of Algeria in 1830. Even as France went on to exert influence in West and Central Africa, its relationship with Algeria has always been unique. Algeria was the only French colony that was considered a part of France and divided into three provinces.

But Algerians living under French colonial rule held an inferior status and were referred to as indigènes, or natives. Most were prevented from going to school, and when Algeria gained independence in 1962, more than 85% of the population was illiterate. Before the Algerian War – which killed between 400,000 and 1.5 million Algerians – historians say one-third of the population had already been wiped out, due to epidemics and invasions.

“There was already a very high level of trauma within the Algerian population, even before the Algerian War,” says M’hamed Oualdi, a history professor of early modern and modern North Africa at Sciences Po-Paris.

What happened in Algeria was in stark contrast to France’s founding principles of liberty, fraternity, and equality. That paradox, say historians, is at the heart of France’s struggles to come to terms with its colonial past.

“Colonial violence creates a problem for France because it has always considered itself a model of democracy,” says Mr. Oualdi. “How can you be a democratic republic and, at the same time, a colonial power that was so violent?”

For decades, France has taken great pride in its conquests of countries across North and West Africa, espousing the glory of the empire in school textbooks while remaining silent on the inhumanities perpetrated. Just after the Évian Accords were signed in 1962, signaling the end of the Algerian War, France passed two decrees and three laws that prevented any pursuit of justice for crimes committed during the war.

The French government did not officially recognize the Algerian War until 1999. And historians continue to request that classified documents from the war be made public in order to see the full extent of crimes.

Other European countries have experienced the challenges of making reparations. In 2021, Germany, after six years of negotiations with the Namibian government, agreed to pay €1.1 billion for what is regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century, against the Herero and Nama peoples. The offer was rejected by the victims’ descendants, who said they were left out of the reparations process and sued the Namibian government this year.

In France, far-right groups have capitalized on these difficulties, glorifying what they consider colonialism’s success stories. After President Macron called colonization “a crime against humanity” during a visit to Algeria in 2017, Florian Philippot, vice president of the far-right National Front party, tweeted, “Mr. Macron, are roads, hospitals, French language, and French culture crimes against humanity?”

Similar debates have cropped up in other conservative bastions. Earlier this year, in the United States, Florida announced that the state’s new social studies curriculum would include lessons that claim slavery helped people “develop skills” that could be used for “personal benefit.”

Some say this is where French educators can provide balance. While there is a national history program, individual teachers have a certain level of freedom in how they teach. But France still lacks a significant body of work on colonialism written from the perspective of the colonized, versus the colonizer. The concept of postcolonial studies has only been present since the early 2000s in France, nearly three decades after its emergence in Anglophone universities.

“French education has always glorified colonialism,” says Benoît Falaize, a French historian and specialist on the history of schools and education. “France constructed hospitals, schools, etc. There is this image of ‘La Grande France.’ How do we put a stop to this colonial trauma from generation to generation? That’s the difficulty educators face.”

“A desire to forget”

As France continues to stall on reparations and repentance, some Franco-Algerians are carving their own path on what those concepts should look like. In 2020, 24-year-old Farah Khodja launched the nonprofit Récits d’Algérie as a way to compile stories of life in colonial Algeria. Like many of her generation, Ms. Khodja spent summers in her mother’s native Algeria without learning the complexities of life under French rule.

That was the experience of Ali, who was born in Algeria and came to live in France at age 25. He says that although his father fought with Algeria’s National Liberation Army, he never spoke about his experiences.

“People of my parents’ generation didn’t talk very much. There was, I think, a desire to forget,” says Ali, now a Paris resident, who is a French public servant and declined to give his last name because he is not authorized to talk to the press. “The suffering they experienced was very deep, and they just wanted to move on.”

Rym Tarfaya, who was born in France to Algerian parents, says her grandparents never expressed hatred or bitterness about Algeria’s colonial – or postcolonial – period.

“They always transmitted memories of that time with a state of serenity,” says Ms. Tarfaya, who spent much of her childhood in Algeria and now lives in Paris. “It wasn’t ‘the mean French’ versus ‘the natives.’ It wasn’t black and white.”

Still, France’s modus operandi after Algeria’s liberation has had consequences for French society today. Immediately after the war, nearly 1 million Algerians resettled in France, causing housing and employment challenges for the French state. New arrivals were placed in public housing in city suburbs, which still suffer poverty, tension, and a lack of resources today.

Harkis – Algerians who fought for the French side during the Algerian war – were one of the groups segregated into ghettos, far from the city center. The French government granted them and their families financial reparations in 2022, when it passed a law that offers an average of €8,800 each to tens of thousands of applicants. But larger battles over reparations still loom.

Relations between France and Algeria remain strained, partly due to France’s inability to officially apologize for not only the eight-year war that claimed 1.5 million Algerian lives, according to Algerian officials, but also the 130 years of colonial rule. In 2021, respected historian Benjamin Stora reiterated in a government-issued report that France did not need to do so.

Because the issue has become so polarized, “the government will have trouble convincing the French electorate to take money out of the state budget to pay reparations,” says French economist Thomas Piketty.

French and Algerian historians met for the first time in April as part of a “memories and truth commission” to discuss the two countries’ history more openly.

“France killed and tortured; it needs to recognize what it did. But I don’t know if the government is capable,” says Rémi Serres, one of the founders of the 4ACG organization and a former French soldier in the Algerian War. He and other members of his nonprofit regularly visit schools to talk about the perils of war and travel to their former battleground as part of aid projects.

“Now, when we go to Algeria, we’re not necessarily welcome everywhere. We mistreated them for 130 years,” he says. “But most people understand that we’re coming as friends.”

This story was produced as part of a special Monitor series exploring the reparations debate, in the United States and around the world. Explore more.

Difference-maker

Where art mends lives, behind and beyond bars

In some places, inspiration can be especially hard to come by. But even in prison, creativity has the power to change the course of an artist’s life.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Riley Robinson Staff photographer

Danny Killion had little interest in art when he was robbing banks in Connecticut. Then he was caught and sentenced to 12 years in prison. “Prison can be a very cold, hard environment,” says Mr. Killion.

Taking Jeffrey Greene’s art workshops offered relief.

The Prison Arts Program has run art classes in Connecticut state prisons since 1978. Mr. Greene, the director, uses classes to create space for artistic exploration and open dialogue, helping students grapple with the past and prepare for a future beyond bars.

Art therapy for incarcerated people can alleviate the mental toll of living in prison, studies show. It’s a benefit Mr. Greene has witnessed firsthand. He has known his students for years, even decades, and has seen how the artistic process helps students deal with issues like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mr. Killion spent 10 years in the Prison Arts Program, learning to concentrate on the artistic process and find solace in a concrete cell.

After finishing his sentence and working in construction, Mr. Killion began creating furniture using driftwood from the Hudson River. In 2013, he opened his own art studio and gallery, Weathered Wood. He traces his transformation back to those first classes with Mr. Greene.

“I don’t know if I would have made it out without that program,” he says.

Where art mends lives, behind and beyond bars

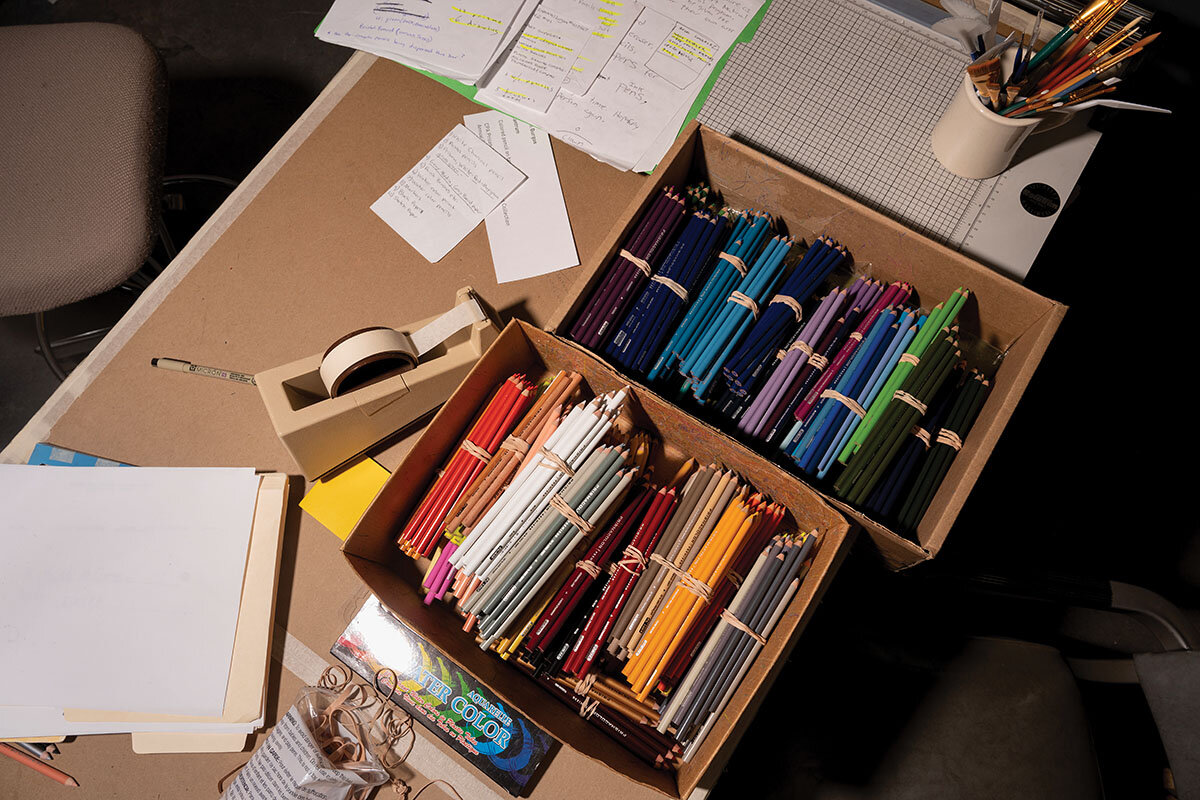

On a long table, Jeffrey Greene prepares bundles of colored pencils for delivery to Connecticut state prisons. Artists have jotted their requests on slips of paper. “White charcoal pencil,” reads one, which also lists pencils in red, may green, and grass green.

Finished artwork lines the shelves of this airy warehouse, home to the permanent collection of the Prison Arts Program. Mr. Greene reaches up to a high shelf and retrieves a model RV, rendered in detail down to the windowsills. The shingles were cut from cardboard with a nail clipper and glued with a mixture of floor wax and nondairy creamer. Another artist unraveled a prison blanket and crocheted the threads into a 3D horse.

The Prison Arts Program has run art classes in Connecticut state prisons since 1978. Mr. Greene, the program’s director and one of the teachers, uses these classes to create space for artistic exploration and open dialogue, helping students grapple with the past and prepare for a future beyond bars.

Art therapy for incarcerated people can alleviate the mental toll of living in prison, studies show. It’s a benefit Mr. Greene has witnessed firsthand. He has known his students for years, even decades. He can describe the medium they use and the metaphors their pieces convey, and has seen how the artistic process helps students deal with issues like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Art unsettles habitual modes of thought and gives you the opportunity to think differently,” says Robin Greeley, professor of art history at the University of Connecticut. “It can disrupt your whole routine and can create a sense of wonder.”

“Incredible empathy”

The Prison Arts Program is one of the oldest correctional arts programs in the United States. It’s the longest-running program of Community Partners in Action, a criminal justice nonprofit based in Hartford.

Since Mr. Greene became the arts program director in 1991, he has worked with more than 12,000 incarcerated individuals. This year alone, he is working with 280 artists and more than 60 “alumni” who are no longer in prison but continue to create art.

Mr. Greene never intended to work in the prison system. After graduating from Hamilton College in New York, he volunteered to teach art workshops in prison on a whim. But he’s never forgotten the impression left by his first day on the job.

“Everyone’s developing in this artificial, man-made, absurd, adversarial environment. It’s ridiculous,” recalls Mr. Greene. In his work today, he encourages artists to reflect on their personal histories for inspiration and motivation.

“What drives Jeff really is the ability to show the humanity of the prison, of the people that are incarcerated,” says Beth Hines, director of Community Partners in Action. “They know they can count on him when they get out.”

In each prison he visits, Mr. Greene instructs his students to create art that only exists because they exist. He says it’s about more than finding a hobby while behind bars: “They are people that are coming out into the world with this incredible empathy and curiosity.” Even if they never leave the prison system, he adds, that mindset can have a positive effect on others.

Restoring families

Despite its shoestring budget, much of the funding for the Prison Arts Program is dedicated to postage, as mailing out artwork has become a way for those who are incarcerated to maintain ties.

For years, Natasha Kinion felt like she’d been swallowed alive in prison. “I was guilt-ridden. I was shameful. I was really broken,” she says in a phone interview.

A mother of four who has experienced domestic abuse and substance addiction, Ms. Kinion spent 13 years at York Correctional Institution in Connecticut. There she started making abstract art.

“It took me at least the first six years of my incarceration to really open up and allow the healing process to start,” says Ms. Kinion. “I began doing a lot of therapy in prison. The Prison Arts Program was amazing for me because I was able to draw out my emotions.”

Mr. Greene helped Ms. Kinion send her artwork to her children. Her daughter Mayonashia Jones once received a drawing of a butterfly trying to fly with broken wings. She remembers thinking of her mom and wondering, “Has she always felt like that?”

The packages became their “love language,” says Ms. Jones in a phone interview, and a foundation for rebuilding their fraught relationship. The experience inspired her to pursue a bachelor’s in fine arts.

Since her release in 2019, Ms. Kinion has published a book about her journey, titled “Stand Up You’ve Been Down for Too Long,” and has opened her own digital art company, Dezigning Deztiny.

“I never told him this ... but Jeff is really my hero,” says Ms. Kinion.

New beginning

Danny Killion had little interest in art when he was robbing banks in Connecticut. Then he was caught and sentenced to 12 years in prison. “Prison can be a very cold, hard environment,” says Mr. Killion.

Taking Mr. Greene’s art workshops offered some relief. “Jeff is this 6-foot-5, floppy-haired hipster – so very warm” in comparison, says Mr. Killion. He spent 10 years in the Prison Arts Program, learning to concentrate on the artistic process and find solace in a concrete cell.

“I’ve never met anyone who’s a more profound teacher,” says Mr. Killion, who finished his sentence in 2007. As he found his feet in society, Mr. Greene would drop by, offering art materials and a listening ear.

After working in construction, Mr. Killion began creating furniture using driftwood from the Hudson River. In 2013, he opened his own art studio and gallery, Weathered Wood, in Troy, New York. He traces his transformation back to those first classes with Mr. Greene.

“I don’t know if I would have made it out without that program,” he says.

This year, Mr. Killion unveiled his first public commission, a sculpture of twisted scrap metal depicting a man breaking through chains, installed at Old New-Gate Prison, a historical site in East Granby, Connecticut. Mr. Greene was there too, both men now standing outside prison gates.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A peace-ward drift might end the Gaza crisis

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The tragic crisis in Gaza has brought a reminder that security for Israel and a just future for the Palestinians are indivisible. This helps explain the intense diplomacy within the Middle East to prevent the conflict from spiraling into a full-blown catastrophe. If that diplomacy helps restore calm, it will rely on a longtime trend in the region: a shift toward moderation within Arab societies over the past half-century.

One poll before the Oct. 7 brutal raid on Israelis found that 62% of Palestinians in Gaza opposed breaking a cease-fire with Israel. Half agreed that Hamas “should stop calling for Israel’s destruction.” The poll found a sharp decline across Arab countries in support for extremist groups.

Another poll in June found that more Palestinians say rooting out corruption and fostering new leadership are more important than armed struggle against Israel.

Those attitudes point to aspirations for an end to the conflict between Israel and Palestinians – not the destruction of Israel, but a renewal of their own societies based on democratic values.

A peace-ward drift might end the Gaza crisis

The tragic crisis in Gaza has brought a reminder that security for Israel and a just future for the Palestinians are indivisible. This helps explain the intense diplomacy within the Middle East to prevent the conflict from spiraling into a full-blown catastrophe on both sides. If that diplomacy helps restore calm, it will rely on a longtime trend in the region: a shift toward moderation within Arab societies regarding Israel’s place in the region over the past half-century.

The numbers bear this out. A Washington Institute poll of Palestinians taken before the Oct. 7 brutal raid on Israelis found that 62% of Palestinians in Gaza opposed breaking a cease-fire with Israel. Half agreed that Hamas, the governing faction in Gaza that launched the attack, “should stop calling for Israel’s destruction.” The poll, published last week, found a sharp decline across Arab countries in support for extremist groups like Hamas – down to just 17% among people in the United Arab Emirates, for example.

Such sentiments show how far the region has changed. In 1967, Arab leaders codified their united rejection of Israel’s right to exist. Six years later, that stance resulted in a coalition of Arab countries invading Israel.

Last week’s surprise attack on Israel by Palestinian fighters – the worst since the war in 1973 – had a very different prologue. Five Arab countries have normalized ties with Israel: Egypt, Jordan, Bahrain, UAE, and Morocco. Sudan, which was part of the 2020 Abraham Accords, has yet to finalize its ties. Saudi Arabia was poised, before the Gaza crisis, to follow with its own agreement.

Trade and other forms of cooperation continue to expand between Israel and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf region. Qatar and Egypt are central peacemakers in international efforts to contain the current crisis. Since 2003, Iraq has been a democracy, not a dictatorship. The rise of the Islamic State's violent caliphate in 2014 was quickly ended.

In a recent interview with Fox News, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman expressed hope that bilateral negotiations with Israel will also “ease the life of Palestinians and get Israel as a player in the Middle East.” Mustafa Barghouti, general secretary of the Palestinian National Initiative, expresses similarly inclusive hopes. “Our goal is more than ending [Israel’s] occupation. It’s about ending this whole system of injustice that is affecting the future of everybody – including, by the way, Israelis themselves,” he said in a recent Al Jazeera podcast.

A poll of Palestinians conducted in June by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research offers a textured view of a region weary of constant conflict, poor governance, and corruption. Just 24% say the development of Islamic movements furthered Palestinian aspirations for self-determination. More Palestinians say rooting out corruption and fostering new leadership are more important than armed struggle against Israel.

Those attitudes are mostly consistent across the region and reflect many of the reasons for the 2011 Arab Spring uprising. They point to aspirations for an end to the conflict between Israel and Palestinians – not the destruction of Israel, but a renewal of their own societies based on democratic values.

“Will it be possible to break out of this endless cycle of revenge and counter revenge?” asked Raja Shehadeh, a Palestinian human rights activist, in a written piece in The Guardian yesterday. “Perhaps realising that revenge doesn’t bring security would be one way to start. ... Only then might this devastating war be a harbinger of change for a better future.”

Mr. Shehadeh’s hope implies a contract – a partnership of shared justice and prosperity already seeded in a region yearning for a future beyond intractable violence.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The truth that sets us free to forgive

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Yvonne Prinsloo

A willingness to see ourselves and others through a spiritual lens opens the door to healing and harmony – even when division and resentment seem entrenched.

The truth that sets us free to forgive

For some time, an individual’s presence in my life had brought to our family hatred and division instead of love and unity, and lies and backstabbing instead of truth and respect. Even a dear friend of many years turned against me because of the lies that had been told. The dark threads of this subtle, undermining evil seemed to run through every aspect of my life.

As a result, I found it very difficult to put into practice Jesus’ counsel “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you” (Matthew 5:44). Honestly, I just wanted this troublesome person out of my life and my thoughts.

Through my study and practice of Christian Science, however, I have come to see that no matter how impossible a happy outcome seems, there is always a solution. Christ Jesus promised, “Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32).

This problem turned me in earnest to my two favorite books: the Bible, and “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science. Science and Health says, “There is but one way to heaven, harmony, and Christ in divine Science shows us this way. It is to know no other reality – to have no other consciousness of life – than good, God and His reflection, and to rise superior to the so-called pain and pleasure of the senses” (p. 242).

As I prayed, my desire to be free of a troublesome person changed to a purer desire to be spiritually minded and to know the truth Jesus spoke of. In other words, to have only the consciousness of Life as God, good, and to see this individual as the entirely spiritual and good creation of God. It was the material belief of both good and evil as real in which I felt trapped. I could not seem to stop talking and thinking about the problem.

I asked a Christian Science practitioner to pray for me so I could find my freedom from these disturbing thoughts. She helped me see that the disturbing thoughts were not really my thoughts. All true thought comes from God and is good, and as His spiritual expression we reflect the divine Mind.

This conversation was just what I needed. I was able to detach the intrusive thoughts from my identity, and it wasn’t long before I could go about my days without even thinking about this person. However, this person was still very present in our lives, so I continued daily to consider what Christ, Truth, was unfolding to me about her and her relationship to God.

Then one day, the biblical instruction “What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder” (Mark 10:9) took on new meaning to me. God brings together that which belongs together and separates that which does not. This released me from the fear and belief that there was another power that could create or allow discord. In God’s loving hands everyone is blessed and in their right place.

Soon after, I learned that the individual would be coming to spend the weekend with our family. A wonderful thought came to me: “Nothing and nobody can stop me from loving.” I knew this must be a message from God because I felt that the room was filled with the peace of divine Love’s presence – the Love that does not require an object to love but just loves.

During our guest’s visit, peace and love reigned, and we had a harmonious weekend. We parted that day with no strife between us, and have not met again since that weekend nearly two decades ago.

Unforgiving thoughts still lurked. But as I continued to gain a deeper understanding of perfect God, and of each of us as made in Love’s spiritual image, I suddenly saw that while I had detached the bad thoughts from myself, I was still attaching evil to this individual. I hadn’t been recognizing only the reality of God, good. The material senses can present only the counterfeit of God’s spiritual and good creation. All that legitimately exists is God and His perfect, pure, righteous child.

I became convinced of this spiritual reality, and the unforgiving thoughts left for good.

Each of us can know the truth – and be free!

Adapted from an article published in the Sept. 25, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

A new lens on the world

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with the Monitor today. We hope you’ll come back tomorrow when we look at what Israel’s war goals are for its invasion of Gaza – and what would come next.