- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- As Gaza war rages, West Bank officials see a path toward peace

- Abortion boosts Democrats at the polls, again. Will it help Biden?

- ‘We have to hold hope.’ How Jewish-Palestinian families cope.

- Congrats! You’re the first in your family to get into college. Now what?

- Uncovering Shakespeare’s rare First Folios – paw prints and all

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

In Mideast and beyond, a war of words

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Talking about the Middle East is always hard. Now, it is becoming almost impossible.

Monday, a Jewish man in California died amid dueling protests, with law enforcement still investigating the circumstances. Tuesday, U.S. Rep. Rashida Tlaib (whom we recently profiled) was censured by House Republicans and 22 Democrats. They cited her defense of a Palestinian chant seen by many as antisemitic. She says it is an “aspirational call for freedom.” Here are takes from a Jewish source and a Muslim source.

Where is the line between antisemitism and criticism? Words are part of the battleground, and finding peace usually requires hearing not just what people say, but also what they mean. Sarah Matusek’s story today shows how some people are overcoming the challenge.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

As Gaza war rages, West Bank officials see a path toward peace

What will Gaza look like after the war? Conversations have already begun, and the Palestinian Authority that governs the West Bank is trying to carve out a significant role. The move is certainly in its self-interest but could also open a door to the long-abandoned peace process.

-

Fatima AbdulKarim Special contributor

Amid calls for a cease-fire in the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, an energized Palestinian Authority (PA) is preparing for the day after.

With the United States and Europe giving Palestinians the most diplomatic attention in a decade, officials in Ramallah, West Bank, see a rare opportunity to revive a moribund peace process, reverse the fortunes of an unpopular and distrusted Authority, and bring Palestinians closer to statehood.

The PA’s priorities: a Gaza cease-fire, opening of humanitarian corridors, and a wider political settlement under which the Authority would return to Gaza. Working alongside Jordan and Egypt, it envisions a peace conference held by the United Nations, not under the less trusted U.S. Negotiations are even underway with Saudi Arabia to offer normalization to Israel as part of a wider deal that would strengthen this initiative.

Officials are holding up the attack by Hamas as proof that attempts at regional peace that have circumvented the Palestinians have failed and that only Palestinian statehood could ensure “stability, security, and peace for Israel and the region.”

“Despite all the difficulties, this horrendous war offers a promising opening,” says Mohammed Hourani, a prominent Fatah member. “We can turn this opening into a historic opportunity for our people if we act wisely and act fast.”

As Gaza war rages, West Bank officials see a path toward peace

Amid calls for a cease-fire in the war between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, an energized Palestinian Authority is preparing for the day after.

With the United States and Europe giving the Palestinians the most diplomatic attention in a decade, officials in Ramallah see a rare opportunity to revive a moribund peace process, reverse the fortunes of an unpopular and distrusted Authority (PA), and bring Palestinians closer to statehood.

“Despite all the difficulties, this horrendous war offers a promising opening,” says Mohammed Hourani, a former Palestinian diplomat and a member of the revolutionary council for Fatah, the dominant faction in the PA. “We can turn this opening into a historic opportunity for our people if we act wisely and act fast.”

Breaking weeks of silence, PA President Mahmoud Abbas spelled out the Authority’s vision to U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken in Ramallah Saturday. The West Bank-based government would only “fully assume our responsibilities within the framework of a comprehensive political solution that includes all of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip,” said Mr. Abbas, according to the Palestinian news agency, Wafa.

The PA’s priorities: a Gaza cease-fire, opening of humanitarian corridors, and a wider political settlement under which the Authority would return to Gaza, which it governed from 1995 to 2007.

PA officials are holding up the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas as proof that attempts at regional peace through Arab-Israeli normalization agreements that circumvented the Palestinians have failed, and that only Palestinian statehood could ensure “stability, security, and peace for Israel and the region.”

But they say they are not willing to come in immediately and “clean up Israel’s mess.”

“We call for a tangible mechanism with a set time frame that leads to an end to the occupation and the establishment of a Palestinian state,” says Social Development Minister Ahmed Majdalani, a PLO Executive Committee member. “But no Palestinian organization or faction will return to Gaza on the back of an Israeli tank.”

A deal the PA can sell

The PA, working alongside Jordan and Egypt, envisions an international peace conference held by the United Nations, not under the U.S., which officials say the Authority has lost trust in as a mediator.

Negotiations are even underway with Saudi Arabia to offer normalized ties to Israel as part of a wider deal that would strengthen this local initiative. Disrupting the U.S.-backed Saudi-Israel normalization talks is thought to have been one target of the Oct. 7 attack.

Talks are gaining traction among the U.S., European Union, and U.N. over a post-Hamas governing body with proposals for a Palestinian authority – Palestinian civil society representatives, not necessarily the Palestinian Authority based in Ramallah. And that is jolting Palestinian diplomats into overdrive to ensure the Authority is not replaced by a new entity in Gaza.

Analysts say the PA is pushing for Israeli concessions in the West Bank and Jerusalem, and for commitments to statehood that it can legitimately sell to a suspicious public.

“The Authority needs something to show to the people that they are not agents of Israel and that all these martyrs and lives lost in Gaza were not in vain,” says analyst Ibrahim Masri. “Otherwise they will be risking their lives, not just their political career.”

In discussions with the U.S., the EU, and Arab states, the PA is also warning: Without a political settlement, more violence may come.

“If Israel continues this violence without offering a political horizon, I believe the explosion in the West Bank will be more violent and bloody” than Oct. 7, warned Mr. Majdalani.

As diplomats work, analysts say, Mr. Abbas has chosen to lie low and wait, believing that the longer the war drags on, the more Hamas will be weakened and the greater the international pressure on Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu to enter a peace process.

Hamas conundrum

Yet while the PA and Fatah push for a relaunched peace process, a nagging question remains: What to do with Hamas?

There is no love lost between the secular Fatah and Islamist Hamas.

Hamas seized Gaza and expelled Fatah from the strip in 2007 amid infighting over contested elections that officials in Ramallah refer to as a “coup,” in which Hamas threw Fatah members from rooftops.

From 2007 to 2022, reconciliation efforts failed.

Officials say Hamas’ Islamist ideology will survive in some form, and its supporters will remain “part of the Palestinian political and social fabric.”

Senior Fatah officials worry that if the PA and Fatah entered immediately into a postwar Gaza, they would face a “bloodbath” and “series of assassinations” by an insurgency of Hamas remnants.

Despite the concerns over a hasty Gaza return, there is also rising confidence within the PA that Hamas will come out of the war severely weakened, isolated, and fractured – allowing the PA to impose conditions on the remnants of Hamas’ political wing or stamp it out as an organized movement altogether.

Unable to publicly criticize Hamas due to public outrage, and to avoid clouding calls for a cease-fire, officials say privately they see the war as a final indictment of Hamas’ unilateral militant approach and reliance on Hezbollah and Iran.

One can detect more than a hint of Palestinian schadenfreude.

“Hamas, as a movement as we know it, is finished,” says one PA official who preferred to remain unnamed. “They can come back to the umbrella of the PLO by accepting the PLO agenda, a two-state solution on 1967 lines, and renounce violence, or they can let the door of history hit their backs on their way out.”

The unpopular PA

Waiting is also risky for the PA and Mr. Abbas.

Should Hamas continue to bog down the Israeli military, its support among the Palestinian people could rise.

While Mr. Abbas and the PA are suddenly sought after by the international community, their support is at an all-time low among an outraged population in the West Bank.

Mr. Abbas has yet to deliver a speech or address the Palestinian public since the outbreak of the conflict.

Israeli settler attacks and military operations in the West Bank have killed 117 people and displaced 1,000 Palestinians from their homes since Oct. 7, PA officials say, further exposing Mr. Abbas and the PA as unable or unwilling to protect citizens.

For many people on the street in Ramallah and Jericho they are, simply, “traitors.”

“Arab countries and protesters in London and New York are taking stronger stances than the Palestinian president,” says Mohammed, a vendor. “This crisis has exposed how the Authority has no authority and is not Palestinian.”

“We know why the PA is in the West Bank, and it is the same reason they want to put it in Gaza: It is a client for Israel and America and it keeps security and their interests.”

Armed clashes have erupted between citizens and PA forces in Jenin, Nablus, and Bethlehem.

“There was little legitimacy and popularity for Abu Mazen [Mr. Abbas] and the PA before the war,” says analyst Mr. Masri. “Now there is zero legitimacy or popularity – but there is no clear alternative.”

To prove its effectiveness as a partner for the West and security partner for Israel, since Oct. 7 the Authority has facilitated an unprecedented wave of arrests across West Bank towns and villages. It provided intelligence allowing Israeli forces to arrest 1,900 Hamas members and suspected sympathizers, would-be militants, and citizens who call for resistance on social media.

Diplomatic sources say the crackdown has impressed Washington and EU officials, who are prodding Israel to strengthen the PA.

It has also fanned the flames of West Bankers’ ire.

“The Authority is facilitating the occupation’s intrusion into every detail of our lives,” says one Ramallah resident whose apartment was stormed by Shin Beit in search of a suspect last week. “If the Authority goes back to Gaza, it will be an Israeli occupation under a different flag.”

Abortion boosts Democrats at the polls, again. Will it help Biden?

Elections in nonpresidential years are scoured for potential hints about the bigger elections ahead. Yesterday’s clear message: Abortion is a winning issue for Democrats. What else could the election mean for next November? Sorry, it’s still too early to know.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Abortion was on the ballot in multiple U.S. states Tuesday, both directly and indirectly, and the message from voters was loud and clear: Keep it accessible.

The off-year election results were a salve to Democrats – especially President Joe Biden. He is running for reelection amid chronically low job approval ratings. Now he’s also facing grim poll numbers in battleground states against former President Donald Trump, the likely GOP nominee in 2024.

In Ohio, now solidly Republican, a ballot measure to enshrine reproductive rights in the state constitution passed easily, 57% to 43%. In Virginia, where Democrats made abortion the No. 1 issue in state legislative races, the party won control of both chambers. And in Kentucky and Pennsylvania, pro-abortion-rights candidates prevailed.

But while Democrats can certainly take heart from Tuesday’s results, as well as other lower-turnout elections since 2016, the 2024 presidential election may be another matter.

With Mr. Trump likely on the ballot and spurring turnout, the challenge for President Biden will be to energize Democratic voters. And while abortion rights and the protection of American democracy remain strong issues for Mr. Biden, presidential elections often turn on the economy and voters’ impressions of the candidates – including characteristics such as age, Mr. Biden’s top liability in polls.

Abortion boosts Democrats at the polls, again. Will it help Biden?

Abortion was on the ballot in multiple U.S. states Tuesday, both directly and indirectly, and the message from voters was loud and clear: Keep it accessible.

The off-year election results were a salve to Democrats – especially President Joe Biden. He is running for reelection amid chronically low job approval ratings and, recently, grim poll numbers in battleground states against former President Donald Trump, the likely GOP nominee in 2024.

In Ohio, now solidly Republican, a ballot measure to enshrine reproductive rights in the state constitution passed easily, 57% to 43%.

In Virginia, where Democrats made abortion the No. 1 issue in state legislative races, the party won control of both chambers – a blow to GOP Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s potential presidential ambitions.

And in Kentucky and Pennsylvania, pro-abortion-rights candidates prevailed. Kentucky, which backed Mr. Trump by 26 percentage points in 2020, was especially heartening to Democrats, as Gov. Andy Beshear won reelection easily. With a reputation for effective governance, the pragmatic Democrat offers his party a model for how to succeed in a conservative state.

Ever since the Supreme Court overturned the nationwide right to abortion in June of last year, reproductive rights have driven Democratic activism, setting Republicans back on their heels. Notably, Mr. Trump has come out against bans on abortion at six weeks’ gestation, calling them “a terrible thing and a terrible mistake” – drawing rare criticism from some fellow Republicans. Many women don’t know they’re pregnant at six weeks.

Virginia was seen as a test case for a “middle ground” – a 15-week ban, with exceptions for rape, incest, and to protect the life of the mother, which is what Governor Youngkin promised if Republicans had won control of the state legislature. But on Tuesday night, that approach did not look like a political winner.

“Republicans don’t like talking about [abortion], but they’ve had to deal with it,” says Larry Sabato, a veteran political analyst at the University of Virginia. “That’s why they came up with this 15-week plan. They hoped it would seem like a compromise.”

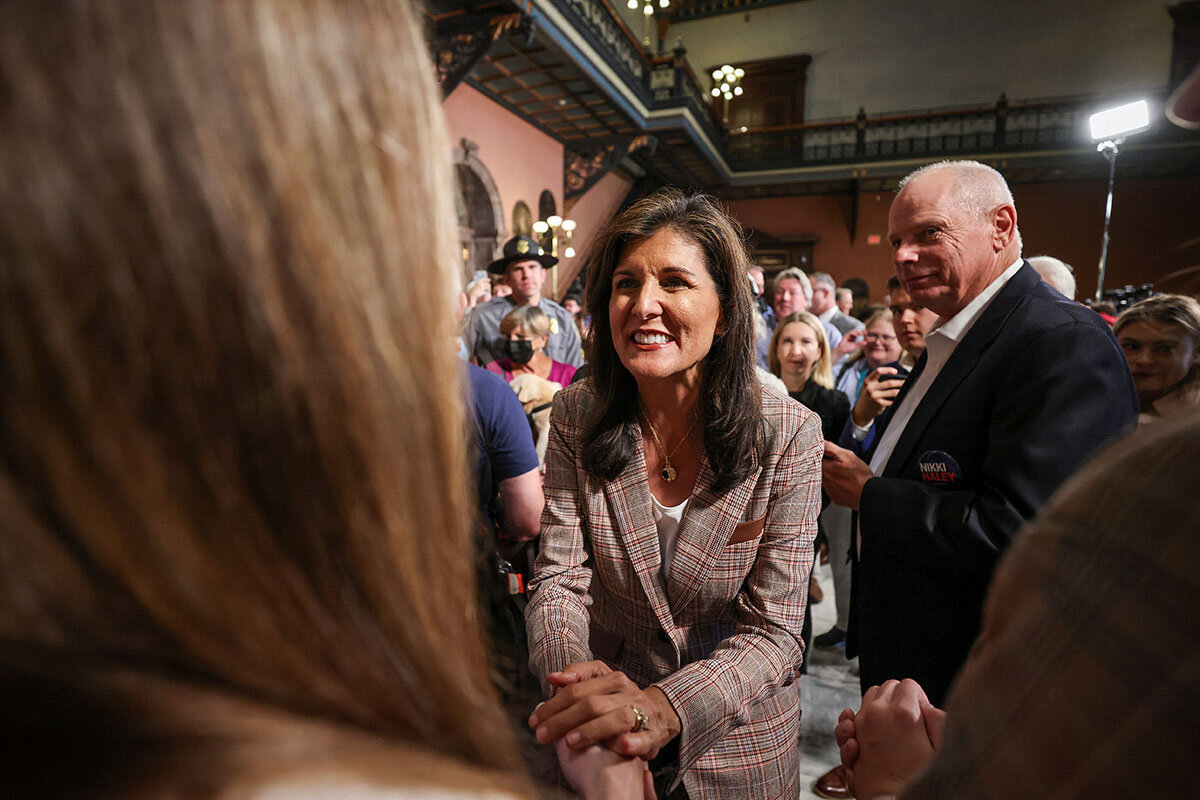

Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley has tried to strike a conciliatory tone on abortion, calling for “consensus” – even as she labels herself “strongly pro-life.” With the former South Carolina governor’s poll numbers rising, all eyes will be on her Wednesday night in the third GOP presidential debate.

In Pennsylvania, a battleground in presidential elections, the Democrat prevailed Tuesday in a state Supreme Court race that focused in part on abortion rights. Democrats now have a 5-2 edge on the state’s highest court, which also played a critical role in litigation around the 2020 election and could do so again in 2024.

Democrats can certainly take heart from Tuesday’s results, as well as other lower-turnout elections since 2016 – including the 2018 and 2022 midterms. But the 2024 presidential election, with Mr. Trump himself likely on the ballot and spurring turnout, will be another matter.

The challenge for President Biden, come 2024, will be to energize Democratic voters. And right now, voters seem to have less positive views of the president than of his party generally. Overall, 71% percent of registered voters in six key swing states say Mr. Biden is too old to be an effective president, according to a recent New York Times/Siena College poll. Even among Democrats, that figure is 51%.

Abortion, along with the possibility of another Trump term, is likely to be a major talking point for Democrats in 2024. The Times/Siena poll showed abortion to be Mr. Biden’s strongest issue, beating Mr. Trump by 9 percentage points. Mr. Biden also wins on handling of democracy by a slimmer 3 percentage points.

But presidential elections typically turn on the economy, and Mr. Biden can’t count on concerns about abortion rights or the future of American democracy to save him. In the six battleground states – Nevada, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan, Arizona, and Georgia – voters said they trusted Mr. Trump on the economy over Mr. Biden, 59% to 39%.

Political analysts stress that the election is a year away, and polling today isn’t determinative. But it still serves as a warning to Democrats that they have their work cut out. The party may get help in 2024 from planned abortion referenda on the ballot in several battleground states, including Pennsylvania, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada. Those could help boost Democratic turnout.

“For most Americans, Roe v. Wade is the standard,” says Democratic strategist Karen Finney, referring to the 1973 Supreme Court ruling that legalized abortion until the point of fetal viability. “People believe the woman should decide with her doctor, her family, her God – not the government.”

In a presidential election, however, policy issues can be subsumed by voters’ impressions of candidates, including individual characteristics such as age. That is Mr. Biden’s top liability.

For now, though, analysts warn against fixating too closely on polls – even high-quality polls, like the New York Times/Siena survey.

“It’s just a measure of today,” says Dr. Sabato. “It’s not predictive at all. I tend to toss these things out. I read them, then I forget about them.”

‘We have to hold hope.’ How Jewish-Palestinian families cope.

As we discussed above, conversation about the Middle East has become a war in itself. Imagine being part of a family with both Israeli and Palestinian ties. But many are making it work. One husband notes: The joint commitment to honor all human life was made “before we got into this marriage.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

As Israel’s war with Hamas enters its second month, anger has also erupted in the United States. Reports of alleged hate crimes are emerging, including death threats against Jewish people at Cornell University in New York and the stabbing death of a Palestinian American boy in Illinois.

Deeper dialogue, however, is unfolding in the quieter realm of private lives, as families with ties to Israel and the Palestinian territories process grief. Many emphasize the humanity of all the affected people. They also see their children as embodying a shared future at stake.

“I feel strongly that I need to resist being polarized,” says Jacquetta Nammar Feldman in Texas, a Palestinian American who is also Jewish. “We have to hold hope for something better.”

One couple in Chicago have reminders of their shared vows – and values – hanging in their living room. Their Jewish and Muslim marriage contracts, the ketubah and the nikahnama, are framed side by side.

Though not always in agreement, “we’ve worked really hard to create a space where we can [listen to] each other,” says Shaina Curtis.

The commitment to honor all human life was made “before we got into this marriage,” adds her husband, Amir Abdullah.

‘We have to hold hope.’ How Jewish-Palestinian families cope.

The parents shield their sons, ages 2 and 4, from how the war hits home. That includes what their father, a Palestinian citizen of Israel, found at his Washington office last month.

Go back to where you came from, the typed note said. “You might get lucky with a missile, and meet your Allah sooner!”

Then, in all-caps, a call for all Palestinians to die.

Waseem AbuRakia-Einhorn’s employer, American University, says it’s investigating the note – and separate Nazi graffiti – with the FBI. “It was terrifying,” says Mr. AbuRakia-Einhorn, who now rarely leaves the house.

Yet he’s pushing himself to speak up – with encouragement from Becca AbuRakia-Einhorn, his Jewish American wife. Her support provides a refuge at home.

“She has a way of calming me down,” says Mr. AbuRakia-Einhorn.

Israel’s war with Hamas enters its second month with hostage and humanitarian crises in Gaza, and Israel grappling with the aftermath of the Oct. 7 Hamas attack. In the United States, amid widespread protests, officials report a spike in threats targeting Arabs, Jews, and Muslims.

Deeper dialogue, however, is unfolding in the quieter realm of private lives, as families like the AbuRakia-Einhorns process compounded grief. Interviewing families with ties to both Israel and the Palestinian territories reveals their impulse to see the humanity of all civilians – and a desire for a cease-fire. They also see their children as embodying a shared future at stake.

“I feel strongly that I need to resist being polarized,” says Jacquetta Nammar Feldman in Texas, a Palestinian American who is also Jewish. “We have to hold hope for something better.”

Supportive spaces amid violence

The Oct. 7 Hamas massacre of more than 1,400 people in Israel, according to the government’s latest count, and capture of about 240 hostages, is the deadliest attack in the nation’s history. The ensuing Israeli bombardment of Gaza has escalated into a conflict that has killed more than 10,000 people there, according to local authorities.

In the U.S., cities and university campuses have seen dueling rallies in support of Israeli and Palestinian causes. Reports of threats and alleged hate crimes are also emerging, including death threats against Jewish people at Cornell University in New York and the stabbing death of a Palestinian American boy in Illinois.

Such reactionary hate is “lamentable, but it’s not unexpected,” when people ascribe blame to particular communities here, says Kenneth Stern, director of the Bard Center for the Study of Hate in New York state.

One Jewish and Muslim couple in Chicago, Shaina Curtis and Amir Abdullah, have built a safe space of their own through listening.

Though not always in agreement, “we’ve worked really hard to create a space where we can do that for each other,” says Ms. Curtis, an educator. “Amir has supported me in allowing me to vent.”

It helps that reminders of their shared vows – and values – hang in their living room. Their Jewish and Muslim marriage contracts, the ketubah and the nikahnama, are framed side by side.

“Are we not valuing Jewish lives right now? Are we not valuing Palestinian lives right now?” says Mr. Abdullah, an actor and board member of NewGround, an interfaith group. The joint commitment to honor all human life, he adds, was made “before we got into this marriage.”

Beyond outbreaks of hate, some families say ignorance of history has its own sting. This is an issue being faced by a Muslim Palestinian American in Massachusetts and his Jewish American wife, who raised their children for more than a decade in the West Bank.

The couple prefer not to publish their names for privacy. The husband has dedicated time explaining Palestinian history to neighbors over cups of tea.

“Why am I patient? Because it’s dear to me,” he says.

Conflict’s impact on children

Patience was key for Ms. Feldman, a Palestinian American, and Lowell Feldman, a Jewish American, when they met in a college chemistry class and started dating. Soon they realized they were taught little about each other’s backgrounds.

“When we met in 1987, during the first intifada, we didn’t think that it would still be like this,” says Ms. Feldman, who was raised Christian and has converted to Judaism.

Now with three grown sons, the couple say they wished they’d spoken up more in defense of humanity on both sides, and shared more about their own relationship publicly.

“We feel like we’ve, in some degree, have failed, you know, our children – because we’re leaving them a mess,” Mr. Feldman says.

Even before the death threat against her husband, Ms. AbuRakia-Einhorn had been reflecting on the future of her sons. Each of them is Jewish and Muslim – and they are Palestinian Americans who are also Israeli citizens.

Their names were intentionally chosen to work in both Hebrew and Arabic, she says, so they “could seamlessly slip between each identity.”

But now, she wonders, “what do you do when neither identity is safe?”

Some like Ms. AbuRakia-Einhorn are thinking through how best to call the conflict. Though Israel declared war against Hamas last month, she says she avoids the word “war” as it suggests aggression “between two countries.” The Massachusetts couple call it an “escalation of the Israeli-Palestinian crisis in Gaza,” and an issue of “colonization and occupation.”

Talking to her children, Mya Guarnieri Jaradat, an American Israeli journalist, says she avoids framing the war as a religious conflict, which to her implies an unsolvable problem. She and her ex-husband, who is Palestinian, are raising their elementary school kids in Florida as both Muslim and Jewish.

“I emphasize with my children that this is a conflict, a political conflict, about land that could be solved,” says Ms. Guarnieri Jaradat. “I don’t want them to feel like their own identities are in conflict.”

The journalist’s explanation to them is that killing civilians is never justified, she says, and everyone deserves to live in peace. Meanwhile, she’s also navigated sensitive conversations with her Palestinian ex-husband, who declined an interview. Ms. Guarnieri Jaradat says she regrets, and has apologized for, insensitive questions early on, such as asking whether he supported the Oct. 7 Hamas attack.

“In my heart of hearts, of course, I know he doesn’t support it,” she says.

Building trust and empathy

It’s hard to understand the conflict in-depth – and with empathy – without in-person encounters, says Ulrich Rosenhagen, interim director of the Center for Interfaith Dialogue at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. That’s why stepping away from social media is helpful, he adds, as that space trains users to see the world in binary terms.

“Trust-building doesn’t work over social media,” says Dr. Rosenhagen, who leads interfaith dialogues with students about the conflict.

Neither is modeling self-care for children always easy. Especially as parents anxiously await news of family survival abroad.

“If I, as a mom, turn off social media, go to bed, listen to some music, you know – they will see that’s how it’s done and they will do it,” says the mother in Massachusetts, whose daughters are now adults.

However, “I don’t think I’ve always been good at that,” she says. “I think my girls will have to learn it for themselves.”

Meanwhile in Texas, Ms. Feldman, a writer, turns to a familiar tool to cope. Seeking respite from grief and survivor’s guilt, she recently wrote a poem to prepare herself to enjoy the wedding of a friend.

Part of the poem, addressed to a weary world, reads:

Your bodies and spirits are broken

But today, here and now

We shall gather the light.

Congrats! You’re the first in your family to get into college. Now what?

Schools have long known that first-generation college students often need financial aid. But they also need “college knowledge” – all the cultural things that help you navigate campuses and fit in. Colleges and other groups are getting savvier about helping first-generation students thrive.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Cameron Russell’s academic journey took him from a small town in Louisiana to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the 50,000 students at the state’s flagship university.

Mr. Russell’s mother, a rural mail carrier, and father, a crawfish farmer, always pushed him toward college, even though they didn’t have degrees. But his family’s encouragement could only go so far.

“As a first-generation student, where do you start? What do you do? How do you prepare for college when no one in your family’s been before?” Mr. Russell says.

He found answers – and financial and academic support – from a relatively recent initiative, the Kessler Scholars Collaborative, aimed at buoying first-generation students.

Undergraduates who are the first in their family to attend college often need help navigating campuses, financial aid forms, and the pressures of cultural change. To aid them – and to broaden the number of people who have access to college – organizations are honing their support to focus on everything that’s needed to achieve a degree.

“Kessler gave me the opportunity to come into my own as a first-generation college student,” says Mr. Russell, who graduated in April and is now enrolled in a Ph.D. program in biochemistry at Emory University in Atlanta. “It really shaped me.”

Congrats! You’re the first in your family to get into college. Now what?

Huanying Yeh’s academic ambition began in 2016 when her family moved to Sacramento, California, from Taiwan. She started high school barely able to speak English.

Her parents would write words from the dictionary on flashcards “and encourage me to join them for a study session,” she remembers.

In 2020, Ms. Yeh was accepted at highly selective Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, which her family couldn’t afford. She hoped she would qualify for need-based financial aid.

That year, the university joined the Kessler Scholars Collaborative, an initiative designed to assist first-generation students academically and financially. Ms. Yeh, whose parents never finished college in Taiwan, became one of the school’s first recipients.

As educators wrestle with the best way to combat declining interest from Generation Z students in attending college, many agree that exorbitant cost is a big factor. For first-generation college students in particular, hurdles can also include not knowing how to navigate campuses, financial aid forms, and the pressures of cultural change as they carry the hopes of their families. To help these undergraduates – and to broaden the number of people who have access to college – organizations are honing their support to focus on everything that’s needed to achieve a degree.

“It’s not just the money that makes it difficult for first-gen students to go to college,” says Katharine Meyer, an educational policy scholar and a fellow at the Brookings Institution. “It’s the college knowledge that’s necessary to go to and through an institution that can be really hard to navigate.”

Over the past decade, more resources and effort have been devoted to first-generation students, who make up over a third of undergrads. The help ranges from online tools, such as the website I’m First!, to an initiative to connect first-generation faculty with students on University of California campuses.

This week, some 200,000 high school seniors who are first-generation or from low-to-moderate-income homes were offered “direct admission” via the Common Application portal based on their grade point averages. In a first, students were learning they had been accepted sometimes before finishing the application. The 70 participating schools are in 28 U.S. states, Education Week reports. Students will know for sure they have a place to attend college, but they will still have to figure out costs and any financial aid.

The Kessler collaborative, which started as a need-based scholarship program in 2008, was revamped in 2017 to focus on first-generation students. Ten new schools were added in 2022, with the help of private funding, and welcomed students this fall. Philanthropists Judy Kessler Wilpon and Fred Wilpon, a first-generation student himself, are founding donors and continue to support the collaborative.

Currently there are 808 Kessler scholars enrolled at 16 public universities and private institutions. Participating schools agree to meet 100% of every student’s financial need with help from Kessler. All of the students have financial needs, and at least 60% of participants are eligible for Pell Grants, meaning they qualify as having exceptional need. Kessler also offers career advising, peer mentoring, and alumni-networking events.

Johns Hopkins, which already had infrastructure in place for first-generation, limited-income students, steered Ms. Yeh toward Kessler, which helped her get a free education. Brent Fujioka, who oversees the initiative at the university, notes that first-generation students are among the “best and brightest” he’s worked with, but that they are “being asked to operate within an institution that wasn’t designed with them in mind.”

The university coaches them to connect with faculty early on and encourages them to find research opportunities. Ms. Yeh, an electrical engineering and public health major, is currently studying the movements of electric fish in altered environments. She ultimately wants to develop health-related technological devices.

“For me, the transition was definitely pretty drastic, because during high school I was still adjusting to the English-speaking community. I wasn’t really involved in a lot of student organizations or the [high school] campus itself,” Ms. Yeh says. “So during college, I was eager to make a bigger impact.”

The stakes are high for first-generation students in terms of future earning potential. Households headed by a first-generation college graduate earn twice what non-college graduate households earn, at around $100,000 and $50,000, respectively, says Richard Fry, an economist and researcher for the Pew Research Center. According to a Pew study, those numbers increase for a second-generation college graduate household to almost $136,000 annually.

Working with first-generation cohorts to help them graduate is a goal of groups like Kessler. Research has shown that more than a third of first-generation students will leave school before completing a degree.

Gail Gibson, executive director of the Kessler collaborative, says making sure students graduate is important. Kessler recently released its first findings on the 2017 inaugural class at Michigan, which graduated in 2021. The results are promising, says Dr. Gibson, who ran the program in those early days.

The inaugural cohort had an 83% graduation rate within four years. This was almost equal to the 84% rate for students who were not first-generation and who started at the same time. Kessler scholars also fared better than other first-generation students who were not associated with the program, whose four-year graduation rate was 75%.

Kessler leaders are learning to pivot as the collaborative progresses. They are focusing on building one-on-one relationships with students on campus, for example, says Dr. Gibson, as opposed to just letting them know services are available. While making a strong push to introduce first-year students to campus life, they have also learned to keep up with programming to help upperclassmen stay engaged.

Cameron Russell, a four-year Kessler scholar at Michigan, graduated in April. He is now enrolled in a Ph.D. program in biochemistry at Emory University in Atlanta. His journey took him from Crowley – a small town in the southern part of Louisiana – to Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the 50,000 students at the state’s flagship university.

His mother, a rural mail carrier, and father, a crawfish farmer, always pushed him toward college, even though they didn’t have degrees. But his family’s encouragement had limitations.

“When you’re just starting out as a first-generation student, where do you start? What do you do? How do you prepare for college when no one in your family’s been before?” Mr. Russell says he asked himself.

“I always had my family’s support to talk to them. But they couldn’t give me advice on Michigan, because they had never been, but also they couldn’t give me advice on how to talk to professors, how to communicate your needs to advisers, or how to find resources at the university,” Mr. Russell says.

He traveled to bitterly cold Michigan his first semester without a winter coat because he didn’t know any better, he says. Other freshmen students, equally green to the new world they’d encountered, left him temporarily flustered when they assumed that he was racist because he was from a small farming community with a different way of living. Things got better.

“Kessler gave me the opportunity to come into my own as a first-generation college student,” Mr. Russell says, adding that “it really shaped me and the community of really great friends who I’ve made through it who all share that first-generation identity with me.”

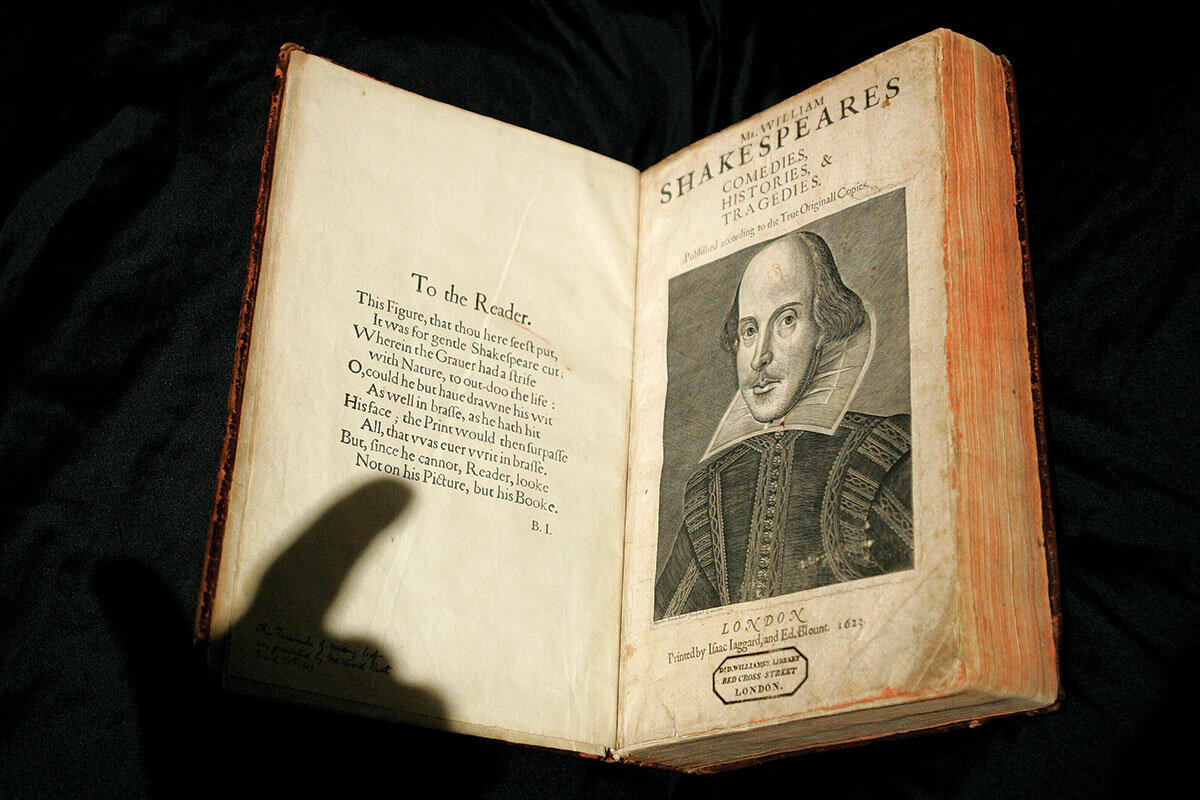

Uncovering Shakespeare’s rare First Folios – paw prints and all

Eric Rasmussen is a Sherlock of Shakespeare. He tracks down and investigates original folios (or collections of work), which can be worth millions. This month is the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folios. What has Mr. Rasmussen seen in his sleuthing? Cat paw prints and bullet holes, for a start.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Roy Rivenburg Contributor

Eric Rasmussen’s work is a combination of “CSI” and “Antiques Roadshow.” For two decades, he has traveled the globe to authenticate Shakespeare First Folios – the earliest printed compilations of the Bard’s plays.

Nov. 8 marks the 400th anniversary of the First Folios’ publication, without which half of Shakespeare’s plays would have been lost.

In his work, Dr. Rasmussen has encountered bumbling book thieves, eccentric owners, quirky historical footnotes, and even a copy with a bullet hole through it.

Although some scholars prefer pristine copies, he favors editions that reflect their past owners, such as the University of Glasgow folio with handwritten comments about the actors. The notes were clearly made by someone in the 17th century who saw the performance.

In another folio, a cat left five paw prints on a page opened to “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Dr. Rasmussen surmises that the owner picked up the offending cat before it could do more damage.

Not all folios that he examines are authentic, of course. But the excitement of a potential discovery energizes his work.

Uncovering Shakespeare’s rare First Folios – paw prints and all

His work is a combination of “CSI” and “Antiques Roadshow.” For two decades, Eric Rasmussen has traveled the globe to investigate and authenticate Shakespeare First Folios – the earliest printed compilations of the Bard’s plays – which celebrate their 400th anniversary this month. First Folios can command millions of dollars when one surfaces for sale.

Along the way, he has encountered bumbling book thieves, eccentric owners, quirky historical footnotes, and even a copy with a bullet hole through the middle (the slug stopped at “Titus Andronicus,” proving that it’s “an impenetrable play,” he says).

The folios were published in lavish fashion seven years after William Shakespeare’s death in 1616 and solidified his stardom. Without them, 18 works – including “Macbeth” and “The Taming of the Shrew” – would have been lost, says Dr. Rasmussen, a professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno. “It’s one of the most iconic cultural artifacts in the world,” he adds.

Dr. Rasmussen’s Shakespeare scholarship dates back to junior high, when he wrote a report comparing “The Tempest” to “Gilligan’s Island.” He learned literary forensics at the University of Chicago, from a professor who used an electron microscope to analyze typeface variations in early texts.

“We can reconstruct what happened in a printing house 400 years ago,” Dr. Rasmussen says, including which typesetters produced which pages. Tradespeople also thought their inking equipment worked better if soaked in urine, which means their shops probably “smelled like a subway,” he adds.

In 2004, he joined forces with Anthony James West, a British business executive who spent most of the 1990s – and much of his personal fortune – tracking down surviving First Folios. Building on a 1902 census that located 152 copies – from an estimated press run of 750 – Dr. West’s legwork boosted the tally to 232. Then, at London’s legendary Reform Club, where novelist Jules Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days” got underway, he asked a research team led by Dr. Rasmussen to retrace his steps and thoroughly document the condition and provenance of each folio.

The seven-year project turned up a slew of oddities. Flipping through the volumes page by page (without gloves, which cause more damage than bare fingers, Dr. Rasmussen says), the folio detectives ran across food and wine stains, rusty silhouettes of scissors used as bookmarks, and margins scribbled with personal notes and math problems.

In one case, a cat left five paw prints on a folio opened to “Love’s Labour’s Lost,” Dr. Rasmussen says. Before the kitty could take a sixth step, it was apparently “snatched off the book,” he adds.

Although some scholars prefer pristine copies, Dr. Rasmussen favors editions that reflect their owners, such as the University of Glasgow folio in which a preface that names the actors in Shakespeare’s troupe is scrawled with comments “by someone who actually saw them perform.”

Other owners have included dukes, bishops, oil barons, a female psychoanalyst who studied under Sigmund Freud, and an 18th-century astronomer with a namesake crater on the moon.

For some collectors, possessing a Shakespeare folio has proved hazardous to their health. “A surprising number died within a year of getting their hands on one,” Dr. Rasmussen says.

Today, most First Folios belong to museums, universities, or libraries. No two copies are alike, thanks largely to typographical errors that got fixed as the press run continued but still made it into print because the paper was expensive and flawed pages weren’t discarded.

In 2011, the idiosyncrasies and histories of each folio were chronicled in two books based on the research of Dr. West and Dr. Rasmussen’s team. The first, a 600,000-word reference, “The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue,” inventoried in “retina-detaching detail” (as one critic put it) every watermark, crease, tear, margin note, and more. It’s the literary equivalent of a fingerprint, Dr. Rasmussen says. The second book, “The Shakespeare Thefts: In Search of the First Folios,” recounted stories for a nonacademic audience.

In recent years, three more First Folios have surfaced – along with a few false alarms – and Dr. Rasmussen commonly gets called to investigate.

“He is a trusted expert – by scholars, auction houses, libraries, and bibliophiles,” says Emma Smith, a Shakespeare authority who has written two books on First Folios and authenticated one of the newly discovered copies. “No one else I can think of has his credibility with these different groups.”

Ayanna Thompson, director of the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, agrees: “Professor Rasmussen’s work has been invaluable for our understanding of First Folios.”

And wannabe First Folios.

Over the last century, news reports periodically swirled that a civil engineering college in Roorkee, India, had a copy – and the book’s dimensions were larger than any other First Folio. Yet no experts had managed to inspect the relic.

Finally, last year, after a new round of articles, Dr. Rasmussen hopped on a plane to settle the issue. Flower bouquets, gifts, and photographers greeted his arrival at the school’s Mahatma Gandhi Central Library, where he was whisked to a gallery that also houses a signed copy of India’s Constitution.

To his surprise, the folio was in tatters. “The fragments reminded me of the Dead Sea Scrolls,” he writes in “Shakespeare’s First Folio Revisited,” a 400th-anniversary collection of essays. “In a moment of romantic reverie, it seemed to me that surely only a survivor from the early 17th century, one that had long endured the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, would be found in such a state.”

But alas, poor Yorick, when Dr. Rasmussen powered up his portable light box – a device normally used for viewing photo negatives and slides – and backlit each of the folio’s 908 pages, he couldn’t find any of the 21 telltale original watermarks. The verdict wasn’t all bad for his hosts, however. Although Dr. Rasmussen concluded the volume was a 19th-century replica, he tagged it as one of the first created via photolithography. That’s rare too, he notes.

A book doesn’t have to be a First Folio to hold a silver lining.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

A big restraint on a wider Mideast war

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Outside of Israel itself, perhaps no other country has closely watched the war in Gaza than Lebanon. As Israel’s northern neighbor and home to an Islamist militant group aligned with Hamas, the country fears it might become a second, full-scale front. Yet as the fighting in Gaza enters its fifth week, that has not happened. One reason may be Lebanese youth.

Since mass protests in 2019 that demanded transparent, secular rule, and then happened again in elections last year, young Lebanese have challenged the political legitimacy and dominance of Hezbollah. That pro-Iran militant group rules the mainly Shiite south and has 150,000 missiles aimed at Israel. In the 2022 elections, Hezbollah and its political allies lost their majority in Parliament.

“There is pressure from Hezbollah’s Lebanese allies, friends and constituents, to step aside and spare Lebanon destruction,” Mohanad Hage Ali, a senior fellow at Carnegie Middle East Center, told Arab News.

Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah may have gotten the message. In his first speech since the attack on Israel by Hamas, he indicated Friday that there will be no major attack on Israel other than recent strikes against Israeli military positions close to the border.

A big restraint on a wider Mideast war

Outside of Israel itself, perhaps no other country has more closely watched the war in Gaza than Lebanon. As Israel’s northern neighbor and home to an Islamist militant group aligned with Hamas, the country fears it might become a second, full-scale front. Yet as the fighting in Gaza enters its fifth week, that has not happened. One reason may be Lebanese youth.

Since mass protests in 2019 that demanded transparent, secular rule, and then happened again in elections last year, young Lebanese have challenged the political legitimacy and dominance of Hezbollah. That pro-Iran militant group rules the mainly Shiite south and has 150,000 missiles aimed at Israel. In the 2022 elections, Hezbollah and its political allies lost their majority in Parliament.

“There is pressure from Hezbollah’s Lebanese allies, friends and constituents, to step aside and spare Lebanon destruction that would have a long-term impact on the population,” Mohanad Hage Ali, a senior fellow at Carnegie Middle East Center, told Arab News.

Only half of Lebanon’s Shiites are in favor of Hezbollah opening a second front with Israel, according to an Oct. 17 poll done for the Lebanese newspaper Al Akhbar. Among other major religious groups (Sunni, Christian, and Druze), support is much less.

Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah may have gotten the message. In his first speech since the attack on Israel by Hamas, he indicated Friday that there will be no major attack on Israel other than recent strikes against Israeli military positions close to the border.

“The last thing [the Lebanese] need is to be dragged into a war on top of their other woes,” wrote Neville Teller, Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review, in The Jerusalem Post. “If Nasrallah tried to involve them, he might find himself facing a popular revolt.” Lebanon has an impoverished economy and a government that has been in a political stalemate for more than a year.

In addition to domestic pressure, Hezbollah may have also calculated that Israel and the United States stand ready to hit the group hard if it launches missiles at Israeli civilians. Iran also may be willing to retain Hezbollah as a proxy weapon against Israel to safeguard its nuclear weapons program.

On Oct. 10, President Joe Biden warned outside actors – meaning Iran and Hezbollah – against taking advantage of the Gaza crisis: “I have one word: Don’t.”

“That was music to my ears,” one Lebanese in Beirut, Ruth Boulos, told Politico. “Let’s hope Hezbollah listens,” she added.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

A healing view of the ‘other’

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Lyle Young

A God-inspired view of others opens the door for hope, peace, and healing – even in the most trying situations.

A healing view of the ‘other’

On Oct. 7, the same day Hamas launched an attack on Israel, I was finishing a book on the Crusades written by a celebrated Lebanese author. The book recounts the Crusades as seen by Arabs, with the author quoting extensively from Muslim historians of that period. It illustrates how the Arab view of that time differs markedly from the Western view, which is still influencing events today.

This left me pondering how we perceive the “other,” especially in the context of the Middle East.

That adherents of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam trace their history back to Abraham is often referenced as a unifying common element. But I’ve found myself especially inspired by something Jesus said: “Before Abraham was, I am” (John 8:58).

Jesus was referring not to himself as a human being, but to the Christ, the divine nature that he exemplified. The reference to “I am” brings to mind another figure who is important to these three religions – Moses. When Moses was instructed by God to liberate the children of Israel from their enslavement, he asked what he should tell them God’s name is. He was told, “I AM THAT I AM” (Exodus 3:14).

Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, put forth a view of the divine I AM’s creation – which includes all that truly exists – that is a helpful foundation for peace. She wrote in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Being is holiness, harmony, immortality” (p. 492). And in the same book, “Man is the expression of God’s being” (p. 470).

This is a profound insight into spiritual identity. While each individual has a history, language, and culture to be valued, what most fundamentally defines us is a “pre-existence” with God. This is not an alternate life, but rather an eternal, spiritual coexistence with God, good – in which we are at one with this one divine source, and therefore at one with each other. In truth each of us is a unique spiritual expression of universal qualities of God, such as joy, intelligence, kindness, and generosity. This fact of spiritual existence predates all human history, including King David, Jesus, Muhammad, and the Crusades.

This gives us a solid basis from which to lift our thought above limiting perceptions that fuel distrust, hate, and violence to a higher view – the spiritual reality, in which we’re all children of God, all brothers and sisters. Though it’s not always easy, especially when the “other” has acted cruelly – whether 10 centuries ago or just last month – we can rely on this absolute truth to elevate our view of the “other” in ways that further healing.

Some years ago someone close to me was killed through wanton violence. While that indeed was a challenging time, I knew that for the good of myself and of those around me I had to not dehumanize the aggressor. That would only have dehumanized me, which would not have brought healing.

Instead, I strove to see the heinous act as distinct from the person’s real, spiritual individuality – that is, who they are independent of human history. That didn’t make that act any more acceptable; indeed, eventually the aggressor was rightly brought to trial and found guilty. It was just that I wanted to see the person the way God sees every one of us, as spiritual and good and created to love, rather than simply writing off the aggressor as a monster.

Thinking about how God sees His children also helped me understand that I can never truly be separated from the person who was killed, because their true, spiritual nature can never be destroyed but is always at one with God, good, as we all are. This one God brought me peace and kept me from falling prey to thoughts of hate and revenge. I harbor only the profound desire that the aggressor gain self-awareness and genuinely reform.

The idea that there is only one God is so essential to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Christian Science it’s understood that inherent in having one God, good, is the power to heal. To again quote Science and Health, “One infinite God, good, unifies men and nations; constitutes the brotherhood of man; ends wars; fulfils the Scripture, ‘Love thy neighbor as thyself;’ annihilates pagan and Christian idolatry, – whatever is wrong in social, civil, criminal, political, and religious codes; equalizes the sexes; annuls the curse on man, and leaves nothing that can sin, suffer, be punished or destroyed” (p. 340).

Healing is clearly needed in the Middle East. But we need not despair. Having one God, one great I AM, who is the divine Parent of all of us, helps us see the “other,” too, as children of God. This is a powerful starting point for nurturing peace in our own hearts. That peace can enable us to strive to honor those apparently lost by bathing the inner wounds of others with Love’s healing balm. Truly, our own peace can help bring peace to the world.

Viewfinder

Read my sign

A look ahead

We’re so glad that you could join us today that we’re offering a special treat – an extra story at no additional charge!

Pakistan has long been the first place of refuge for many Afghans, which happened again after the Taliban takeover in 2021. But the Pakistani government has now begun raids to expel 1.7 million Afghans. The shift is supposedly about security, but many Pakistanis are mystified – and demanding more compassion. Click here to read the story.