- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A small peace offering in the Middle East

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Howard LaFranchi’s moving story today of the family of a kidnapped Israeli is well worth a read. But Howard tells me there’s also a story behind the story worth sharing.

Howard’s driver that day was a Palestinian Israeli. About a half-hour into the interview, the driver called Howard from the car, sounding nervous. A man had come out of the building to confront him: Was he Hamas?

The man soon entered the apartment, agitated and demanding something in Hebrew (which Howard does not speak). The family Howard was interviewing calmed the man, and he left. When Howard returned to the car after the interview, the driver proudly showed him a cup of coffee. The man who not long before had thought he might be a Hamas member had brought it. A small peace offering in a land yearning for them.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Amid war’s gloom, Mia’s family yearns for shining star’s return

In a war where brutality seems to be in flood tide, Howard’s story is about a mother seeking an eddy in the inhumanity. Her daughter was taken in the Hamas attack. She knows the days since have put her at the center of a complicated crisis that has divided the world. But like so many caught in the middle, she just wants her child to be safe.

Mia Schem was attending the Nova rave in the desert near the Gaza border on Oct. 7 when Hamas fighters staged their surprise attack. Their rampage through small communities and the music festival killed more than 1,200 people, sparking an unforgiving Israeli bombing campaign and ground invasion in which more than 11,000 people have been killed and much of Gaza destroyed.

Mia was one of some 240 individuals abducted that day and taken to Gaza. Now, a month later, the hostages’ families are living with the terrible knowledge that their loved ones are the one slim sliver of humanity that has had to endure the violence and trauma of both Oct. 7 and its aftermath.

The Schems are French Israeli, and so Mia’s mother, Keren, has met with senior French officials, including President Emmanuel Macron. And yet, she says that mostly when she goes to bed at night, she worries that the hostages are slipping from the world’s attention.

“She is loyal, she is warm, and she is something like the rock of our family,” Keren says of Mia. “And I know these are the things any mother would say,” she adds, “so I ask every mother, every father, every sister ... brother, ‘Just think about it for one minute; think about [the hostages] like they are your own.’”

Amid war’s gloom, Mia’s family yearns for shining star’s return

Keren Schem rubs two fingers over the tiny-script Hebrew tattoo that encircles her wrist like a bracelet, and offers her best English translation.

“You are the only star in the sky, you are bright and shiny,” she says. Still looking down at the words her fingers caress, she says, “Every day I am praying to God that Mia is seeing a star in the sky.”

Keren Schem is the mother of Mia Schem, one of the estimated 239 hostages that Hamas, the militant organization that rules the Gaza Strip, is presumed still to be holding captive in Gaza.

Mia was attending the Nova rave in the desert near the Gaza border on Oct. 7 when Hamas fighters staged their surprise cross-border attack. They rampaged through small communities and the music festival, killing more than 1,200 Israelis and other nationals, and wounding and sexually assaulting many more.

Then there was the unprecedented mass abduction of hostages back to Gaza, all, like Mia, the bright and shiny lights of some family somewhere, but mostly, like the Schems, in Israel.

The Hamas attack sparked an unforgiving Israeli bombing campaign and ground invasion in which more than 11,000 people have been killed and much of Gaza, an area less than 1/15th the size of Delaware that 2.3 million Palestinians call home, destroyed.

And now, a month after the mass abduction, the hostages’ families are living with the terrible knowledge that their loved ones are the one slim sliver of humanity that has had to endure the violence and trauma of both Oct. 7 and its aftermath.

“Mia is strong; she is very brave,” Keren Schem says. “But every day I worry how even she can handle all of this.”

Seated in her sun-splashed, stark-white apartment in Shoham, the tidy community near Tel Aviv’s Ben-Gurion Airport that is 21-year-old Mia’s home, the single mother of four describes the daughter she misses terribly. With Mia’s older brother, Eli, at her side and Tyson, the family dog, underfoot, she implores the world to remember the hostages as if they were their loved ones.

“Mia is 10 million times more beautiful on the inside than the outside – and she is beautiful,” she says. Mia paints; she cooks for her family. Before Oct. 7 she was planning to launch her own tattoo studio.

“She is loyal, she is warm, and she is something like the rock of our family,” Keren says. “And I know these are the things any mother would say,” she adds, “so I ask every mother, every father, every sister ... brother, ‘Just think about it for one minute; think about [the hostages] like they are your own.’”

Information void ... then rumors

Keren recounts the excruciating hours and then days of an information void that followed after receiving the one piece of evidence that Mia had been caught up in the attacks: an Oct. 7 text message Mia sent to a friend, imploring, “They are shooting at us, help come save us.”

Then on Oct. 16, Hamas released videos of two hostages confirming they were being held captive. One was Mia. To her family, she says, “Please get us out of here as soon as possible.”

And since then, nothing.

The Schem family has been subjected to the ups and downs of the hostage issue: what she calls the “rumors” of imminent releases, the news of high-level diplomatic negotiations across the Middle East.

Keren recalls the elation she felt with the news that two women would be released – “Please yes! Let it be my baby” – and the bittersweet letdown when indeed two women were released Oct. 23, after two others days earlier. But Mia was not one of them.

And she is aware that this week is producing another flurry of release rumors.

Indeed, President Joe Biden has dispatched his Middle East envoy, Brett McGurk, to the region to pursue what U.S. and other officials confirm privately could be a “swap” deal of up to 70 female and child hostages for an equal number of women and children among Israel’s hundreds of Palestinian prisoners and detainees.

Community support

On a personal level, Keren Schem says she couldn’t expect more from her community.

“Shoham is the best you could ask for. They bring food every day; they ask what you need and how they can help. That’s something good you can say about Israelis,” she adds. “We are there for each other no matter what.”

Indeed, in Israel one month after the attacks, it is impossible to go a day without multiple reminders of the hostages, from posters demanding, “Bring them Home Now!” which hang from overpasses and balconies, to flyers plastered everywhere with photos from a happier time.

Every day there are rallies and other observances aimed at keeping the hostages top of mind – like Sunday’s women-only demonstrations that filled big-city squares and small-town public spaces alike, including the central traffic roundabout in Shoham.

The Schems are French Israeli, and so Keren has met with senior French officials, including French President Emmanuel Macron and Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna. On a trip that Keren and Eli took to France last week, they met France’s first lady, Brigitte Macron, as well as two former presidents.

And yet, she says that mostly when she goes to bed at night – one eye on 10-year-old daughter Danny, who since Mia’s kidnapping has been sleeping in her bed – her mind wanders from all the terrible questions she asks herself about Mia to worries that the hostages are slipping from the world’s attention.

“I know this is one of the most complicated crises the world knew, and I can’t believe I’m part of it,” Keren says. “But I ask everyone to remember that maybe this happened in Israel, but it is a crime against humanity. And if this evil is not stopped,” she adds, “it will get to their children and wives, their babies.”

A sense time is running out

President Biden, in addition to his other diplomatic efforts, has been pressing Israel for a four-to-five-day “pause” in its campaign in Gaza to allow for significant humanitarian aid deliveries and the release of some hostages.

On Monday, White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan characterized negotiations for a hostage release deal as “continuing to make progress day by day, hour by hour.” Hamas, which released a video and photograph of an Israeli hostage who it said was killed by Israeli shelling, also released a video of three Israeli women calling on Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to do more to secure their release.

But for Mia’s family, the diplomacy is taking too much time – something it fears that for the hostages could be running out.

“We know people are working on this, but for Mia and the other hostages it’s been a month already,” says brother Eli. “I’m believing in my heart that Mia is alive, but part of me has to know that she could be dead.”

And that would be unbearable for Eli, whose voice cracks and who pauses, briefly unable to speak, when asked what Mia has meant to him.

“You have to know Mia,” he says. “She has so much love and she is so mature; you think she is like a mom or a big sister,” not the slightly younger sister she is.

Despite her focus on Mia, Keren says she also worries every day about the impact the family ordeal is having on her other children.

She worries about her 17-year-old son, Ori, who unbeknownst to her spent his nights after Oct. 7 poring over Hamas videos and the fighters’ GoPro recordings posted online, exposing himself to the atrocities they committed, desperate to see if he could catch some glimpse of Mia.

She worries about Danny, who only Monday agreed to return to school, convinced by her mother that she had to start “getting back to normal.”

A family tattoo

As for Eli, he is planning for the day Mia returns.

“If you spend all night thinking what Mia is feeling, who is she with and how is she living, you can go nuts,” he says. “So I try to think what it will be when she is home.”

His sister will make kubbeh, the hearty dumpling soup she loved to prepare for her family. She will paint, perhaps in the style of Frida Kahlo, whose portrait is on the family apartment wall.

“When she is back, she will make a tattoo for all of us, she will,” says a resolute Eli.

And that tattoo, what will it be?

“I think,” he says, “it will be written, ‘Mia.’”

‘When will this end?’ In Gaza, tough questions from kids.

In Gaza, meanwhile, simply making bread has become a feat of ingenuity. Taking a shower is a dream. Children can now tell the difference between the sounds of artillery fire and rocket fire. They ask adults: What will happen to us? Will we stay alive? Says one mother: “I cannot answer.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ghada Abdulfattah Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

One question gnaws at Shayma Abu Libda, as it gnaws at parents like her across the Gaza Strip. When will this war end?

“I kept telling my children, ‘It will only be a few days, and it will pass,’” says the mother of three, her voice heavy with uncertainty. “Now I am no longer able to answer them.”

That’s a dilemma facing parents up and down the Gaza Strip, where Israeli bombardments over the past five weeks, responding to the savage Hamas attack on Oct. 7, have forced 1.5 million people from their homes and killed upward of 11,000 Palestinians.

City kids, such as Um Mohammad Malalhy’s six offspring, are always pointing out how strange things are in Rafah, in southern Gaza. And it’s not just their surroundings. The children can also distinguish between the artillery fire they heard at home in Gaza City and the missile fire they are now enduring.

Nesma AlHalaby, a journalist and mother of two, says her children’s questions do not stop: “What will happen to us? Will we stay alive? Do we have to leave again to live safely? Why is everybody dying?”

“I cannot answer most of those questions in a way that will calm their hearts and reassure them," she says.

‘When will this end?’ In Gaza, tough questions from kids.

One question gnaws at Shayma Abu Libda, as it gnaws at parents like her across the Gaza Strip. When will this war end?

“I kept telling my children, ‘It will only be a few days, and it will pass,’” says the mother of three, her voice heavy with uncertainty. “Now I am no longer able to answer them.”

Israel’s five-week bombardment of the Gaza Strip, its response to the savage Oct. 7 attack by Hamas, has killed more than 11,000 people, nearly half of them children, Gazan medical sources say.

Flattening neighborhoods, the assault has also forced over 1.5 million Palestinian residents to flee their homes, according to estimates by the United Nations, which has warned that its humanitarian aid effort would come to a halt on Tuesday because of a lack of fuel for its trucks.

The Israeli army has declared daily “humanitarian pauses” allowing civilians in Gaza City, which is now on the front line, to escape the fighting and head south down one major traffic artery. But that road does not necessarily lead to safety: Shelling and missile strikes continue in the south of the Gaza Strip.

Food and medical supplies are dwindling. The few hospitals still functioning are admitting only emergency cases. Their morgues are overflowing: Humanitarian aid trucks are bringing in burial shrouds, and the dead are being placed in mass graves.

In Deir al-Balah and Rafah in southern Gaza, overcrowded with displaced families, the air is often thick with black smoke as refugees burn cardboard, dried palm fronds, and other refuse in an attempt to bake bread.

Families whose homes have yards allow displaced Palestinians in Gaza to make fires on which to bake – taking a single pita loaf as payment. Adding to the smoke is the smell of the burnt vegetable oil now being emitted by taxis that are using the oil in lieu of diesel.

None of Gaza’s bakeries have fuel or electricity to make bread, according to the U.N., which means that bags of wheat flour stocked in U.N. warehouses in Gaza cannot be put to use. On Monday the Food and Agriculture Organization declared the Gaza Strip “food insecure.”

Pink missiles with daisies

As the humanitarian crisis deepens, once mundane activities such as taking a shower, eating a sweet, or drinking a glass of clean water have become dreams to many people here. Finding a few hours of safety is a luxury, and during the lulls, families seek ways to hold out hope for their children – and themselves.

Ms. Abu Libda fled her home in northern Gaza several weeks ago with her three children of ages between 1 and 6. First they sheltered in a school run by the U.N. Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), which administers humanitarian aid in Gaza, but it was overcrowded, so they came south to live with Ms. Abu Libda’s mother and 21 other relatives.

With an opportunity now to rest, the reality of the war, and its impact on her children, is sinking in, she says. “I’m always wondering how I can wipe such bad memories and horrors from their minds.”

To take her older children’s minds off things, she gives them pens and paper. Using vibrant pinks, and decorating the image with daisies, they draw missiles landing on children.

“Sometimes I joke and laugh because I don’t want to think of rockets and want to forget what we are going through,” says Ms. Abu Libda. “But they cannot.”

Other city kids, such as Um Mohammad Malalhy’s six offspring, are always pointing out how strange things are in Rafah, where they are currently sheltering with hundreds of others in an UNRWA school, compared with their home in Gaza City.

But it is more than just the surroundings that are unfamiliar. The children can also distinguish between the artillery fire they heard at home and the missile fire they are now enduring.

“I miss home. I miss my toys,” complains 7-year-old Arwa. “Yalla Mama, let’s go home and live by ourselves.”

“At the beginning we used to tell the children, ‘Tomorrow will be better; we will return,’” Ms. Malalhy says. “I do not know when this war will end, and our whole apartment complex has been leveled. I am afraid that even once this war ends, we will have nowhere to go.

“This war is so different,” she adds. “It is more difficult than any previous war to the point that I cannot lie to my children.”

“Water is a luxury”

Nesma AlHalaby, a journalist and mother of two from Gaza City, has few answers for her children when they ask why they have had to move three times in the last four weeks despite her promises that each new place would be safe.

“Their questions do not stop: What will happen to us? Will we stay alive? Do we have to leave again to live safely? Why is everybody dying?” says Ms. AlHalaby. “I cannot answer most of those questions in a way that will calm their hearts and reassure them.”

She promises them, “When the war ends, I will buy you a cake, and whatever toys you want.”

But, in reality, “I am afraid of what will happen after the war,” she says.

At the Rafah UNRWA school, Arwa’s mother, Ms. Malalhy, races to line up for the water truck to fill up containers, though more often than not the water is not clean enough to drink safely.

“All I want is to quench my thirst and my children’s thirst without worrying about falling ill,” Ms. Malalhy says. “I do not want them to dehydrate, but clean water is a luxury we simply don’t have.”

Hala Baraka, a nurse at Al-Aqsa Hospital, which is one of the last few operational hospitals in the Gaza Strip, is surrounded by loss: A missile strike killed her sister, her nieces, and her nephews.

“I can’t help but feel that my sister and her family were somehow lucky to have been taken from us early on” in the war, Ms. Baraka says. “At least we had the opportunity to retrieve their bodies from the debris and bid them a proper farewell.”

Meanwhile, wounded people, and there are estimated to be 27,000 of them, are finding little relief.

People suffering from injuries such as broken legs, slipped discs, and burns say they cannot find antiseptic or painkillers at depleted pharmacies in southern Gaza, hobbling from pharmacy to pharmacy on makeshift crutches.

Outside an UNRWA school in Rafah, a 12-year-old boy with a broken arm stands by the road looking for a taxi to take him to the European Gaza Hospital; the handful of ambulances that still have fuel are reserved for those who are seriously wounded.

He waits silently, clutching his arm, tears rolling down his cheeks.

Supreme Court adopts ethics code. Will it restore trust?

Supreme Court justices had no code of ethics, until now. The new document lays out no penalties, and most of the rules will be enforced ... by the justices themselves. Yet with public confidence in the court at an all-time low, doing anything is a positive step, experts say.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

For the first time, the Supreme Court of the United States has adopted a formal code of conduct.

The 14-page document, issued this week and signed by all nine justices, comes after months of public pressure over alleged ethical lapses. It codifies what until now had been an informal ethical standard governing the high court. It also comes after favorable views of the Supreme Court reached an all-time low this summer.

Whether the code’s existence itself will be enough to restore that trust remains to be seen. The code features the word “should” 53 times but is silent on what will happen if a justice veers from ethical standards outlined. And that, legal-watchers say, is a startling omission.

The lack of a code is “something that has been a glaring oversight for so many years. ... But when it came time to put pen to paper, I think they fell short,” says Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, a nonprofit advocating for more transparency in the federal judiciary.

But it’s positive the court has responded to that public pressure, he adds. “They represent all of us in one way or another – not in how they decide cases, but as an institution. And on institutional practices, there should be public pressure.”

Supreme Court adopts ethics code. Will it restore trust?

For the first time, the Supreme Court of the United States has adopted a formal code of conduct.

The 14-page document, issued this week and signed by all nine justices, comes after months of public pressure over alleged ethical lapses. It codifies what until now had been an informal ethical standard governing the high court. It also comes after favorable views of the Supreme Court reached an all-time low this summer, according to Pew Research Center.

Whether the code’s existence itself will be enough to restore that trust remains to be seen. The code features the word “should” 53 times but is silent on what will happen if a justice veers from ethical standards outlined. And that, legal-watchers say, is a startling omission.

The lack of a code is “something that has been a glaring oversight for so many years. ... But when it came time to put pen to paper, I think they fell short,” says Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, a nonpartisan nonprofit advocating for more transparency in the federal judiciary.

But it’s positive the court has responded to that public pressure, he adds. “They represent all of us in one way or another – not in how they decide cases, but as an institution. And on institutional practices, there should be public pressure.”

For much of the year, the justices have faced questions about alleged ethical improprieties. The public scrutiny began with ProPublica reports detailing undisclosed gifts that Justice Clarence Thomas has received for decades from billionaire Republican donors, ranging from vacations and private jet travel to forgiven loans and tuition for a relative. Reports allege that Justice Samuel Alito also failed to disclose subsidized vacations. Justice Sonia Sotomayor and Justice Neil Gorsuch faced questions about publishing sales and questions of recusal.

While all other members of the federal judiciary are subject to the judicial code of conduct, the justices largely have policed their own compliance. The code aims to “dispel this misunderstanding,” the statement added, that “unlike all other jurists in this country, [the justices] regard themselves as unrestricted by any ethics rules.”

“It is certainly significant that the court has finally adopted a code of conduct. ... It reflects that the public pressure and public attention about the court’s ethical shortcomings is having an impact,” says Alicia Bannon, director of the Judiciary Program at the Brennan Center for Justice. But “it was a real missed opportunity for the court to really get serious about ethics.”

What’s in the code?

The document features five canons of conduct for justices on and off the court, including recusal standards, and a commentary elaborating on the code. The code doesn’t appear to address the central concern many have with Supreme Court ethics rules: Enforcement is for the most part left to the justices themselves.

For example, a justice “should keep informed about [their] personal and fiduciary financial interests” and “make a reasonable effort to keep informed about the personal financial interests” of their spouse and children, the code states. Justices are supposed to seek guidance from the court’s Office of Legal Counsel and relevant judicial committees. There are no details on who or what would be making sure the justices make these efforts.

At times, broad and vague language leaves it unclear where the line is between proper and improper conduct. There are clear examples of when a justice should recuse themselves from a case, for example, such as when someone a justice or their spouse knows is a party to the case or representing a party in the case. But a justice should also recuse themselves “in a proceeding in which the Justice’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” the code states.

Lower court judges, meanwhile, must follow mandatory recusal rules. Parties in lower courts can also file a motion asking for a certain judge to recuse themselves.

The general language in the code “does suggest [the justices] consider this [as] aspirational, as opposed to binding,” says Carolyn Shapiro, co-director of the Institute on the Supreme Court of the United States at the University of Chicago-Kent College of Law.

“There’s an extraordinary amount of discretion involved in applying these standards,” she adds. But “I’m not sure it would be possible to write standards that don’t have that as an element.”

Does the high court need more leeway?

In a summary, the justices claim that the Supreme Court needs to have more relaxed ethical rules than lower courts do. Most appeals courts are made up of at least 11 judges, for example, whereas there are only nine justices.

“The loss of even one Justice may undermine the ‘fruitful interchange of minds which is indispensable’ to the Court’s decision-making process,” the summary reads. “Much can be lost when even one Justice does not participate in a particular case.”

The document does acknowledge that more may need to be done to firm up the new code of conduct. The court “will assess whether it needs additional resources,” it says. And the Office of Legal Counsel will “maintain specific guidance [for] recurring ethics and financial disclosure issues,” as well as provide annual training to justices and their staff.

The fact the document exists at all is noteworthy. As the high court admits, many of the rules aren’t new, but they have never been formally articulated for the public. That by itself is worthy of recognition, experts say, but the code’s deficiencies are as well.

“If you accept that the Supreme Court is differently situated than lower court judges, it makes it even more important to implement ethical safeguards on the front end to make sure ethical issues don’t emerge in the first place,” says Ms. Bannon of the Brennan Center for Justice.

“The North Star needs to be: Are you preserving public confidence in the judicial system?” she adds. “Here there was a missed opportunity to really put in place safeguards that avoid putting justices in situations in the first instance that would undermine that confidence.”

Recovery in Ukraine: When horses do the whispering

The grief and pain that Ukrainian soldiers can suffer on the front line is sometimes beyond the reach of doctors and therapists. Horses, though, can help.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

For several years now, the Arion riding club outside Odesa has been offering “hippotherapy” – treatment based on the use of horses – to children with physical and psychological disabilities.

Now they are trying it on wounded Ukrainian soldiers. Since the summer, the club has welcomed psychologically traumatized or physically injured men and put them astride horses, to benefit from the animals’ comforting gait.

Or sometimes just their presence. Some soldiers prefer to do their breathing and relaxation exercises while they walk alongside their animals. “The environment itself is relaxing,” points out Mariia Ivashura, the club’s owner, riding teacher, and therapist. “They see dogs, cats, and horses. That reminds them of their childhoods.”

Whether a soldier will return to the front after his course of hippotherapy depends on a military commission; professional soldiers tend to recover more quickly than volunteers and conscripts “who were simply not ready for what they were seeing and experiencing,” says psychologist Oksana Mosiychuk.

But the riding school gives everyone “mental relief,” she says.

“I can’t describe the emotions,” comments one veteran, walking his horse round the paddock. “But I am sure that I will sleep well tonight.”

Recovery in Ukraine: When horses do the whispering

Sitting astride a calm chestnut mare, his eyes closed, the soldier draws in a deep breath. Then he surrenders his mind and his body to grief. He buries his face in the horse’s mane, lets out a muffled sob, and breathes with the heavy steadiness of a runner determined to finish a long race.

“Healing has its highs and lows,” says Flint, as the Ukrainian soldier is known, after guiding his horse at a walk twice around the paddock at the Arion riding club, on the outskirts of Odesa. “The recovery process can be good, but it can also be bad. Right now, I am working on stabilizing my mental health.”

His mind has plenty to process. When a Russian tank shell hit his unit’s position in the eastern region of Donetsk, several of his comrades were killed. He helped another, who had a severe open stomach wound, walk to safety while administering ad hoc first aid as best he could. The trauma and grief of such terrible moments returns in waves.

“I am in a down moment,” he acknowledges, leaning on a crutch by the stables. “When I get bad news about my buddies dying at the front, it is difficult.”

Soothing sunsets

The Arion equestrian club has been offering hippotherapy, as horse therapy is known, to soldiers like Flint since the summer. Its team had already been working for five years with children with varied physical and psychological disabilities when it decided to take on the challenge of treating soldiers. Its mission is to provide a haven of peace and healing to those scarred physically and mentally by the violence of war. It’s a volunteer effort.

“We decided we wanted to do something to have an impact in this war,” says Tetiana Cherevata, a former TV health journalist who has found a new calling in hippotherapy – a practice that is slowly gaining ground in Ukraine. “Many people come to us mentally burned out because of what they have seen at the front line.”

Hospitals and other official institutions choose and send soldiers to Arion’s twice-weekly, two- or three-hour sessions, timed to coincide with the soothing effect of sunset. They might suffer from a stutter, resulting from seeing their friends killed, or from anxiety, or from sleep-related problems ranging from insomnia to night terrors.

“We see all kinds of cases of the brain not working the way it should as a result of trauma,” says Ms. Cherevata. And the riding school also treats patients with war-related physical ailments that can run the gamut from shrapnel wounds to body strain related to use of heavy gear.

Nothing to be aggressive about

Those who feel up to it ride a horse while doing breathing and relaxation exercises. Others – who may have a fear of riding – do similar exercises walking alongside the animal. “The soldiers who come to us are very sincere and open,” she adds. “They understand the value of life and so they are open to everything. They don’t have the hang-ups and hesitations of regular people.” They often return to the front line after two or three weeks of treatment.

Many soldiers struggle with aggression, but none has blown up at the school. “The environment itself is relaxing,” points out Mariia Ivashura, the club’s owner, riding teacher, and therapist. “They see dogs, cats, and horses. That reminds them of their childhoods. There is nothing to be aggressive about here.”

The riding club boasts 23 horses, but only three are considered fit for the job of healing soldiers. Therapy horses not only need to have the right temperament. They also need to be the right shape – not too tall, not too skinny, and not too wide – so that they are comfortable to sit on and do not strain the hips or backs of physically damaged riders.

“You have to take care of a horse,” says Ms. Cherevata, a cheerful redhead who delights in feeding all the horses before going to work. “That takes your thoughts off your problems. It’s a bonus feature: When you feed a horse a carrot or an apple, you can’t help but smile.”

“I will sleep well tonight”

Psychologist Oksana Mosiychuk has been accompanying veterans to the riding club for the past four months. All of them have been combat soldiers dealing with blast injuries. “Some of them return to the combat zone,” she says. “Others simply can’t, due to their health problems. A special military commission decides on that.”

Much depends on a soldier’s background, says Ms. Mosiychuk.

Recent army volunteers and conscripts have limited training and fighting experience, she points out. “They come from all walks of life. Some are taxi drivers, IT specialists, veterinarians, or schoolteachers. They simply don’t have the skills. They just went out to protect their homes, their families, and their country. They were simply not ready for what they were seeing and experiencing, mentally or physically.”

Professional soldiers, on the other hand, “have a greater capacity for recovery because they have been through special training and know how to perform tasks under pressure and follow orders,” Ms. Mosiychuk says.

Ukrainian men are not always receptive to psychological treatment, Ms. Mosiychuk has found. But they are often very partial to animals. The opportunity to be around horses, and the cats and dogs that play alongside them, is something most of them treasure. “Even those who are afraid of riding a horse ... get the mental relief of just being here,” she says. “They go back to the hospital relaxed.”

Fox, the code name of a taciturn soldier who turned up for treatment along with Flint, prefers to walk alongside the chestnut mare, Gesha, rather than ride her.

“I can’t describe the emotions,” he says. “But I am sure that I will sleep well tonight.”

Reporting for this story was supported by Oleksandr Naselenko.

Points of Progress

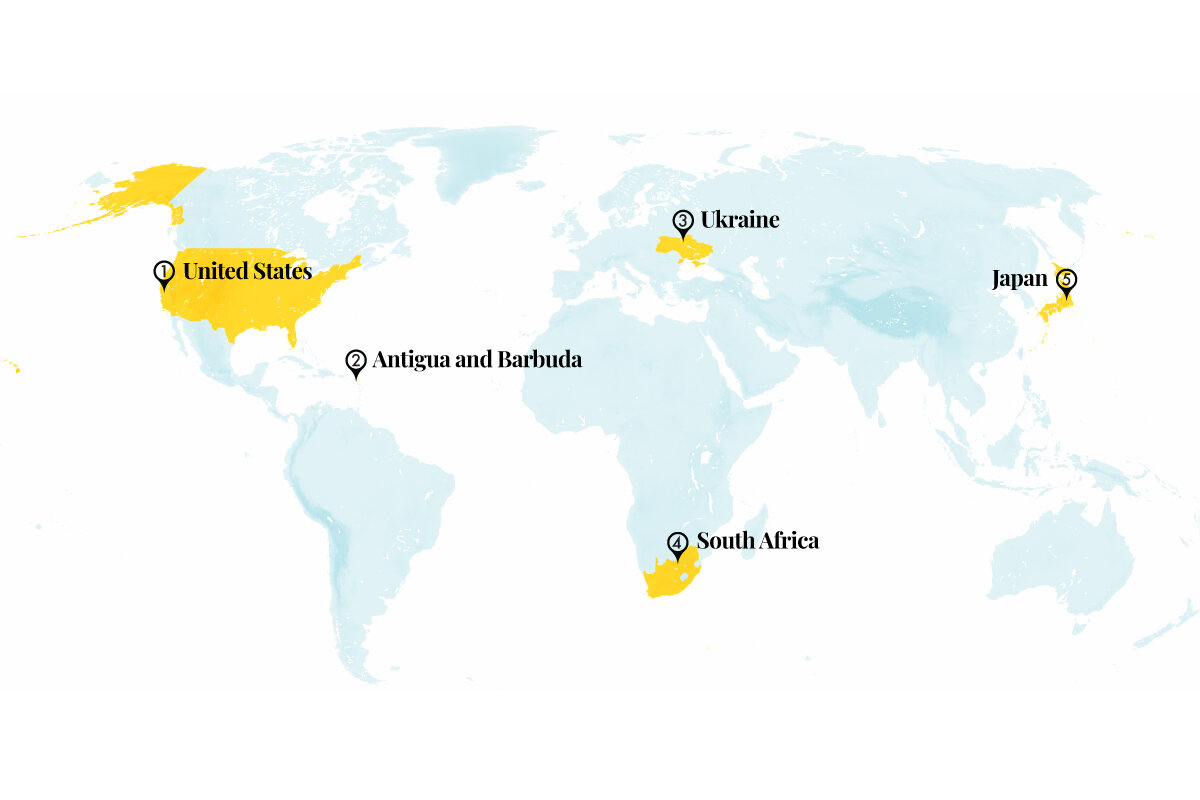

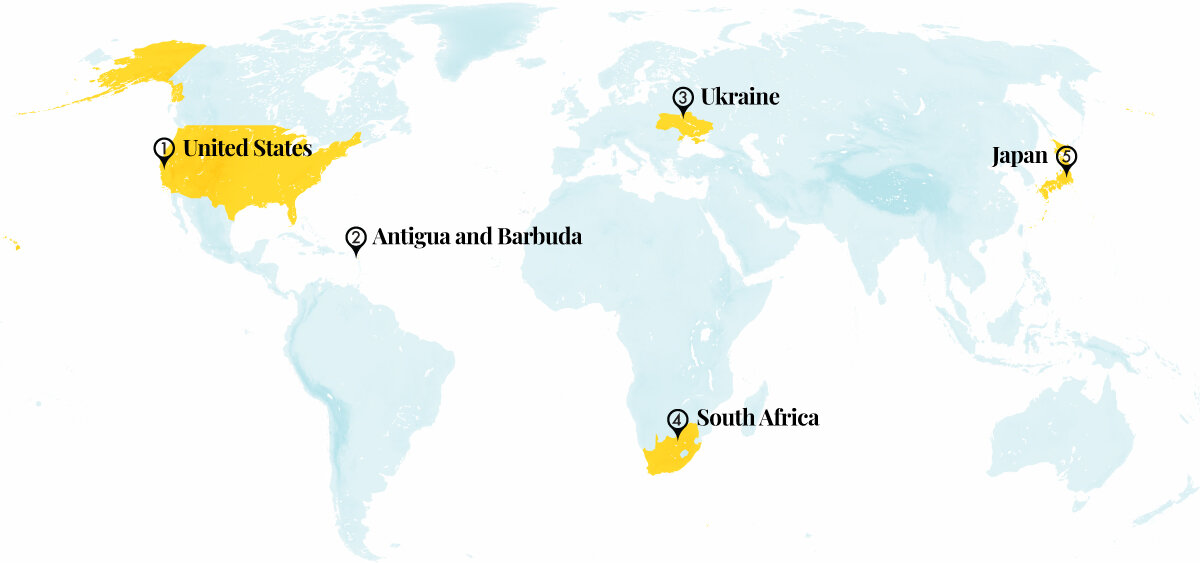

Telehealth for Ukraine and night school in Japan

In our weekly roundup of progress around the world, we have carbon accountability in California, a reawakened island in the Caribbean, and good news for the white rhino. Night schools in Japan are also expanding opportunity.

Telehealth for Ukraine and night school in Japan

1. United States

In a sweeping move toward accountability, California will require large companies to disclose their carbon emissions. Senate Bill 253 applies to roughly 5,400 companies that do business in the state and have annual revenues exceeding $1 billion. By 2026, companies will have to report emissions from energy used and the indirect emissions of the generation of that energy. By 2027, they must disclose “Scope 3” indirect supply chain emissions, such as from employee travel and shipping of goods.

Though many large companies already calculate their carbon emissions, SB 253 will force stragglers to catch up and standardize emissions reporting. The law’s reporting mandates are based on the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, a widely used international standard. The state will allow companies to reuse emissions records filed in other jurisdictions to simplify reporting.

Among other environmental laws signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom in September is a companion law, SB 261. The two bills together are the most extensive climate disclosure laws in the United States. SB 261 says that “economic actors” risk harm to communities without adequate planning and will require more than 10,000 companies to report climate-related financial risks and mitigation and adaptation plans.

Source: Fast Company

2. Antigua and Barbuda

Conservationists transformed a barren island of Antigua and Barbuda into a wildlife sanctuary, fulfilling the country’s part of the global “30x30” goal to protect 30% of the planet by 2030. The island of Redonda was devastated in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by guano mining operations that left behind invasive black rats and goats. In 2016, a local and international consortium began removing rats and goats from the island, transporting the goats – many of which were starving due to lack of food – off the island via helicopter.

The island rebounded quickly. Native trees and grasses resprouted, and seabirds such as the red-billed tropicbird returned.

Conservationists say the population of the critically endangered Redonda ground dragon, endemic to the island, has increased thirteenfold since 2017. Established in September, the Redonda Ecosystem Reserve spans nearly 30,000 hectares (114 square miles) of land, coral reefs, and seagrass meadows.

The Environmental Awareness Group, a local environmental organization, installed cameras to watch for rats and is monitoring local fishing activities. A 2022 study of invasive species removals on 1,000 islands around the world said that such efforts were 88% successful. The organization hopes to reintroduce more species, such as the burrowing owl, to the island.

Sources: BBC, Mongabay

3. Ukraine

Telehealth is helping Ukrainians access services from volunteer health care professionals in Europe and the United States. Experts estimate that amid war with Russia, 1 in 4 Ukrainians – and 60% of Ukrainian soldiers – are experiencing mental health issues such as anxiety and post-traumatic stress. Yet Ukraine does not have enough mental health providers to support everyone, and the conflict has further disrupted access. TeleHelp Ukraine is helping bridge the gap.

Co-founded in April 2022 by Ukrainian native Solomiia Savchuk, a medical student at Stanford University, the group recruits licensed clinicians and language interpreters for a free health service accessible to any Ukrainian with internet. In 16 months, TeleHelp Ukraine provided 1,400 people with virtual consultations with professionals from cardiologists to therapists. Sessions are often in Ukrainian, with an interpreter, though some patients opt for English sessions.

The World Health Organization and U.S. Agency for International Development are among the groups that have also mobilized to improve Ukrainians’ access and break down the stigma of seeking mental health care. “Against the background of daily alarming news ... it doesn’t seem appropriate to ask yourself ‘How are you?’” Ukrainian first lady Olena Zelenska said. “But in fact, psychological well-being and understanding of what is happening in our inner world is more timely than ever.”

Source: Reasons to Be Cheerful

4. South Africa

Africa’s white rhino population increased for the first time since 2012. Conservation efforts resulted in a 5.2% increase in rhino populations last year, according to estimates announced by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Rhinos once roamed widely across Africa and Asia, but hunting, poaching, and habitat loss have driven population levels to less than 5% of the half-million that lived in the early 20th century. The only northern white rhinos, for example, are a surviving mother and daughter that live under 24-hour protection in Kenya. The southern white is near threatened, the only one of five rhino species that is not critically endangered. Rhinos are critical drivers of biodiversity, creating and regulating habitats for other species.

The International Rhino Foundation has praised the creation of large protected areas like Kruger National Park in South Africa, but poaching remains the rhinos’ biggest threat, as poachers move on to target smaller reserves. In January, the treasury departments of the United States and South Africa partnered on a task force to disrupt the illegal trade of rhino horns. And in September, the African Parks foundation acquired a privately owned white rhino breeding project. Over the next decade, the foundation will attempt to rewild and rehome 2,000 white rhinos and push for more stringent local protection for the animals.

Sources: ABC News, International Union for the Conservation of Nature

5. Japan

Night schools are offering a second – and first – chance at education. Following World War II, public junior high night schools offered students who could not complete their compulsory nine years of education an opportunity to learn. Japan does not recognize home-schooling, and in 2016, a law required local governments to provide classes for children 15 and under who have dropped out of regular school.

But the night schools have also increasingly come to serve foreign nationals who want to learn Japanese or finish ninth grade. About 60% to 80% of night school students have foreign roots.

Night schools offer a slate of subjects from math to physical education. At the country’s newest night school in Iwata in the Shizuoka prefecture, instructors emphasize “team teaching,” with several teachers in a classroom at once teaching students based on their level of learning and Japanese language ability.

Some school officials hope that night schools can offer even more support for foreign nationals. “Non-Japanese residents and children with foreign roots have difficulty in learning Japanese and in other aspects of education,” said Hideo Nishida, the principal in Iwata. “I hope public night junior highs can be a hub.”

Sources: The Asahi Shimbun, The Mainichi

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

From fear to freedom for women

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Sometimes a simple idea is all it takes. In 2000, Mexico City added female-only train cars on its subway system. The concept soon spread – to Tokyo, Lahore, and Rio de Janeiro. Now that rethinking of how public transport can meet the needs of female passengers is at the heart of other shifts in urban design. What started as an attempt to shield girls and women from sexual abuse is shaping remedies to many problems.

Public transportation consciously designed around women, argues Kalpana Viswanath, an urban planner based in Haryana, India, is essential to building communities. In much of the world, women’s daily movements are based on tending to the needs of their families. “If you put the care economy center stage [in urban design], you also allow men to be better caregivers,” said Dr. Viswanath.

A new World Bank study of gender-based transportation reforms in Cairo, Beirut, and Amman showed that such measures can have a “robust” impact on female economic participation. But they also have a more complex social benefit. All-female subway cars, for instance, have helped women in Japan find freedom from the fear of sexual harassment during their daily commutes.

From fear to freedom for women

Sometimes a simple idea is all it takes. In 2000, Mexico City added female-only train cars on its subway system. The concept soon spread – to Tokyo, Lahore, and Rio de Janeiro. Now that rethinking of how public transport can meet the needs of female passengers is at the heart of other shifts in urban design. What started as an attempt to shield girls and women from sexual abuse is shaping remedies to many social and economic problems.

Public transportation consciously designed around women, argues Kalpana Viswanath, an urban planner based in Haryana, India, is essential to building communities. In much of the world, women’s daily movements are based on tending to the needs of their families. “If you put the care economy center stage [in urban design], you also allow men to be better caregivers,” Dr. Viswanath told the authors of a newly published collection of interviews with international women who are rethinking urban environments. “It is the work of care that makes us human. We should foreground that in any infrastructure, service, amenity, or public space that we design and plan in our cities.”

The benefits of making public transportation female-friendly are measurable. The average rate of female literacy in the Middle East and North Africa is 88%, for example, yet women make up just 19% of the regional labor force. India faces similar discrepancies. Women there contribute to just 17% of the gross domestic product despite rising female enrollment in higher education. If women’s economic participation were equal to that of men, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates, it would add $28 trillion to the global economy.

Solving that discrepancy can sometimes be simple. In India, for example, the state of Karnataka recently made bus travel free for female passengers to boost employment and school attendance. A new World Bank study of gender-based transportation reforms in Cairo, Beirut, and Amman showed that such measures can have a “robust” impact on female economic participation.

But they also have a more complex social benefit. All-female subway cars, for instance, have helped women in Japan find freedom from the fear of sexual harassment during their daily commutes. In more restrictive, male-dominated societies, meanwhile, orienting public transportation toward women has become a focal point of equal rights.

“The cultural change in mobility ... is a moment of opportunity,” Janet Sanz, former deputy mayor of Barcelona, Spain, told the Local Governments for Sustainability blog last year. “What we do now is to prioritize people.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The church service that changed my life

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Pamela Myers

There’s kindness, warmth, and healing inspiration to be found at Christian Science services – including the annual Thanksgiving service.

The church service that changed my life

Twenty-one years ago, a friend invited me to attend a Thanksgiving Day service at his local Christian Science Society. Little did I know that it would change my life.

For 10 years prior to this invitation, this friend had been so supportive. When my husband no longer wanted to be married, my friend helped me navigate the divorce with encouraging words, never making a harsh, judgmental comment or suggestion. Over the following year, he continued demonstrating God’s pure love and care, including me in many dinners, special occasions, and holiday events with his family. The genuine and selfless care, comfort, and love I experienced was the deciding factor in my attending that Thanksgiving Day service in 2002.

When I arrived, the church was peaceful. Beautiful worship music was playing, and members were kind and friendly. I felt so calm and surrounded by love. Just seeing the words “God is Love” (see I John 4:8) on the wall gave me a sense of warmth and security. I had been raised in another Christian denomination and had spent 45 years as a member of various other congregations. The atmosphere was much different at my friend’s church. I attended services regularly for eight months.

As time passed, I remarried and started attending the church my husband belonged to, which was of another denomination. I gradually drifted back into a routine of activities and attendance there, but felt that the joy and comfort and the true, spiritual meaning of the Scriptures and the Lord’s Prayer were lacking.

For the next 18 years, my heart and soul missed what I had experienced at my friend’s Christian Science Society. I realized that I needed the spiritual nourishment it offered.

So, in 2021 I made the decision to once again attend a service at that society. The same loving elements were present: peaceful music, beautiful hymns, encouraging Bible readings, and an inspiring Bible Lesson-Sermon from the “Christian Science Quarterly” (composed of passages from the Bible and from “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by Mary Baker Eddy).

It had been nearly 20 years since I had first attended, but now my heart and mind were open to hear and know the truth that God is ever-present Life and Love. My return brought a sense of God’s presence and quenched the thirst in my heart and soul. Psalms 42:1 says it well: “As the deer pants for the water brooks, so pants my soul for You, O God” (New King James Version). My heart and mind were once again being nourished.

On May 22, 2022, I became a member of that society. God’s timing is always perfect. Eighteen years could not diminish my longing for a greater understanding of His true nature as Life, Truth, and Love.

Since my return to Christian Science services two years ago, I have had a significant physical healing through prayer. Following a bad fall caused by tripping over a stool in the dark, I prayed for wisdom and strength. The loud thump of my fall woke up my husband. Seeing the blood on the floor, he wanted to call an ambulance, thinking I would need stitches.

But I assured him that I was fine and that God was caring for me, and I cleaned myself up. Even with a split lip and a loose front tooth, I remained calm, knowing that all would be well.

This fall occurred around midnight on a Saturday. The following morning, I emailed several church members, and asked for prayer, as I planned to attend the service in spite of my appearance. The members couldn’t have been more kind or supportive. I experienced no pain.

A few weeks later, I had a routine dentist appointment, and the dentist warned me that a scar would form on my upper lip. But I continued to pray silently during and after the exam. I am happy to report that my tooth is no longer loose, being seated firmly and in perfect alignment with my other teeth, and there is no scar on my upper lip!

Today, I am content and joyful, and feel blessed each day to demonstrate and share divine Truth and Love with others. It’s good to be home.

God does so much more than just heal our physical hurts. Mrs. Eddy explains in Science and Health, “Spirit imparts the understanding which uplifts consciousness and leads into all truth” (p. 505).

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, Nov. 24, 2022.

Viewfinder

A meeting about healing and dignity

A look ahead

We’re grateful you joined us today. Tomorrow, we’ll take a look at the question that determines most presidential elections, no matter what else is going on: How is the president doing on the economy? We visit one key swing county – and get a more nuanced answer than one might expect. People are feeling relatively upbeat, but there’s plenty of blame for President Joe Biden, too.

In the coming days, I’ll also talk to our correspondent Taylor Luck on the remarkable reporting that he and Ghada Abdulfattah have done from the West Bank and Gaza, respectively. So stay tuned for that.