- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

India grants bail to Kashmir Walla editor Fahad Shah

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

After more than 21 months in jail, Fahad Shah, the Monitor’s correspondent in Kashmir, India, has been granted bail. He is expected to be released this week.

Mr. Shah, founder and editor of The Kashmir Walla newspaper, was imprisoned for publishing “anti-national content.” What he and his colleagues at The Kashmir Walla actually did was to report widely and honestly about events in Kashmir, where journalists operate in an increasingly oppressive and hostile atmosphere.

Throughout his imprisonment under India’s Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), he was repeatedly granted bail, only to be charged with a new offense and denied release. The challenges for Mr. Shah were considerable: He struggled with health challenges and isolation, and the paper he cherished has closed in the face of profound financial and professional pressure. The major charges under the UAPA have been dropped, but he will have to stand trial for three lesser charges.

The granting of bail is a crucial first step to ensuring that the rule of law prevails. We – and Mr. Shah’s colleagues – extend our great appreciation to the many readers who took a strong interest in his case. We also salute not only Mr. Shah but also the young staff members of The Kashmir Walla, who have stood up for journalistic integrity and commitment to their colleague despite enormous hardship.

We will report the full story of Mr. Shah’s detention and release very soon.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

In West Bank, Palestinian farmers face settler attacks in war over land

We’ve written about the alarming rise of violence in the West Bank. Under cover of the war in Gaza, armed settler groups are intimidating Palestinians on land essential to a future state. Here we take a closer look at how farmers and villagers are struggling to hold on to their lands and livelihoods.

-

Fatima AbdulKarim Special contributor

Across the West Bank, Palestinian communities are being threatened daily by armed and emboldened Israeli settlers with violence, death, or forced displacement. Settlers’ harassment has gone on for years, but the situation has exploded in the last six weeks.

Yet more than revenge for Hamas’ Oct. 7 assault, the attacks mark the acceleration of a systematic campaign by Israel’s far-right to cantonize the West Bank and render any future Palestinian state unviable, diplomats and organizations say.

Emerging flashpoints include remote Bedouin encampments and farming villages scattered across territory that is under full Israeli military control. The communities are now squarely in the crosshairs of militant settlers based in nearby illegal outposts.

“For anyone who cares about a Palestinian state, these populations are critical,” says Allegra Pacheco, head of an organization devoted to protecting the West Bank communities.

Areas of the West Bank under direct Israeli military control are dotted with illegal settler outposts placed to create Palestinian-free zones that connect existing settlements and encircle Palestinian villages, nongovernmental organizations say.

The targeting of certain communities “is not sporadic,” says Dror Sadot, spokesperson for the Israeli NGO B’Tselem. The settlers “are doing what they dreamed of doing for so many years. ... [They] know no one is watching them, and all eyes are on Gaza.”

In West Bank, Palestinian farmers face settler attacks in war over land

The masked men arrived at Suleiman Muleihat’s caravan home at midnight, driving olive-green all-terrain vechicles and dressed in military fatigues, with what looked like brand-new M16 rifles slung over their shoulders.

Mr. Muleihat’s family, living under Israeli military occupation on the slopes above Jericho, was used to the army. But these men did not act like the army.

They demanded his ID and attempted to storm his home.

They threatened to kill him, he says, and were only repelled by his dog, who rushed in to defend him. The masked men shot and killed his dog before driving off.

For his Bedouin clan’s village, the incident last week characterized just another night.

Across the West Bank, Palestinian communities are being threatened daily by armed and emboldened Israeli settlers with violence, torture, death, or forced displacement.

No longer knowing who is a settler, who is an Israeli soldier, or where to turn, Mr. Muleihat and other residents say one thing is clear: Since Hamas’ attack on Israel Oct. 7, and with war raging in Gaza, it has become a life-and-death struggle to remain on their land.

“They are trying to wear us down and make our lives unbearable. We can’t sleep because that is when they will come, midnight, 1 a.m., 2 a.m.,” he says, rubbing his bleary eyes after a late-night shift as village watchman. “But we are steadfast. They will have to kill us to take us off our land. If no one is watching, they will try.”

Systematic campaign

West Bank settlers have been stepping up attacks and harassment for years. But the situation has exploded in the last six weeks.

The United Nations and international organizations have expressed alarm, and demand that Israel rein in settlers have gathered steam. France has condemned the violence as a “policy of terror.” And U.S. President Joe Biden, in a Washington Post op-ed Saturday, said militant settlers “must be held accountable,” and said his administration is “prepared” to start “issuing visa bans against extremists attacking civilians in the West Bank.”

Despite pledges from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel has responded only minimally. Attacks are mounting.

Coming on top of stepped up Israeli military raids across the West Bank, there is concern the attacks could provoke an outbreak of wider unrest and even a new war front.

More than revenge for Hamas’ Oct. 7 assault, the settler attacks mark the acceleration of a systematic campaign by Israel’s far-right to cantonize the West Bank and render any future Palestinian state unviable, say international organizations, Israeli nongovernmental organizations, and Western diplomats.

“For anyone who cares about a Palestinian state, these [village] populations are critical,” says Allegra Pacheco, head of the West Bank Protection Consortium (WBPC), a European Union-funded grouping of NGOs devoted to protecting West Bank communities from forcible transfer.

From Oct. 7 to Nov. 15, the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs recorded 244 settler attacks resulting in the deaths of eight Palestinians, including one child, and 50 injuries.

In less than six weeks, settler violence displaced 1,149 people, including entire communities, compared with 1,105 people in the previous 21 months. An additional 6,000 Palestinians are at “imminent risk” of displacement, says the WBPC.

Emerging flashpoints include remote Bedouin encampments and farming villages scattered across territory that is under full Israeli military control, where the Palestinian Authority can only provide education and health services.

Bedouin communities, which move seasonally to graze their livestock, are now squarely in the crosshairs of militant settlers based in nearby illegal outposts.

In Farisiya, a remote community in the lush northern Jordan Valley, Ali Abu Hussein now keeps his 300 sheep penned, unwilling to venture out since Oct. 7.

After countless death threats and amid daily harassment, he and other shepherds in his community fear crossing the road to their adjacent lands.

“They are surrounding us and cutting us off from water and pastures. They won’t let us live or make a living,” says Mr. Abu Hussein.

To keep their flocks alive, he and other Bedouin herders are trucking in feed at $450 per ton, depleting their savings.

Blurred lines

With West Bank settlers called up as reservists since Oct. 7, Palestinians and Israeli activists say the line between settlers and soldiers is increasingly blurred. According to the Israeli NGO B’Tselem, the killer of a Palestinian harvesting olives last month was an off-duty reservist.

In half the recent settler attacks, Israeli forces accompanied or supported the attackers, according to the U.N.

The 60% of the West Bank that is under direct Israeli military control is now dotted with illegal settler outposts placed to create Palestinian-free zones that connect existing Israeli settlements and encircle Palestinian towns and villages, NGOs say.

“The outposts were strategically placed in areas to break up the Palestinian territorial continuity and disconnect Palestinian communities from each other,” says Ms. Pacheco.

The repeated targeting of certain communities “is not sporadic,” says Dror Sadot, a B’Tselem spokesperson. “They are doing what they dreamed of doing for so many years – to take more and more land.

“The settlers know no one is watching them, and all eyes are on Gaza.”

Attempts to speak with the armed settler groups were unsuccessful.

“The settlers are using the [Oct. 7] tragedy to advance their agenda; they couldn’t be happier,” says Guy Hirshfeld, an Israeli volunteer with a group that spends nights in Bedouin villages and accompanies shepherds, in the hopes that the presence of an Israeli with a camera will prevent violence. With settlers firing live rounds, activists no longer believe even they are safe.

“We are at the front lines”

Khan al-Ahmar is a ramshackle collection of tents and shacks on the eastern outskirts of Jerusalem between the settlements of Kfar Adumim and Maale Adumim. It’s populated by Bedouin from the Jahalin tribe who were pushed off their lands in 1948 and settled here under Jordanian rule.

“We are at the front lines,” Khan al-Ahmar community leader Eid Jahalin says as he points to a settler outpost a few hundred yards away.

“If we were to leave, Israel and Israeli settlers would completely encircle Jerusalem and cut the West Bank in half. All Palestinians will suffer and have their movements completely restricted,” he says.

Settler drones now fly into the village regularly, enter the schoolyard, and terrify livestock. Settler gunmen visit regularly.

The Israeli military has imposed a 5 p.m. curfew on the community, and settlers from the nearby outpost threatened to shoot youths who wander onto the main road, Mr. Jahalin says.

“Any street, any field in the West Bank can become a firing zone. We spend every waking moment looking over our shoulders,” says Khalid Allawi, who says he is being blocked by armed settlers from reaching his 124 acres of farmland adjacent to his village of Deir Jarir, deep in the West Bank.

Adding to the terror is the spike in kidnapping attempts, kidnappings, and torture of Palestinians carried out by settlers, the photographs of which are shared on social media.

With Israel seemingly unable or unwilling to stop the violence, Western embassies and Israeli human rights advocates say their material assistance and monitoring is no longer enough to prevent the displacement of unarmed Palestinians facing gun-toting settlers.

“We need security, armed guards, or police – the one thing the international community and the [Palestinian] Authority cannot provide us,” says herder Fathi Allawi.

Displaced Palestinians face “tougher future”

The uprooting of communities since Oct. 7 has had a domino effect.

“When families give in and leave, they make our lives a thousand times more difficult for the rest of us who remain,” says Mr. Muleihat in Jericho. “It convinces the settlers that their campaign is working and motivates them to increase the violence.”

The future of those who have been pushed off their lands is highly uncertain.

One year after they left their ancestral home of Ras al Tin, selling their flock of 300 sheep after settlers killed a relative, Omar Kaabneh and his family are living in makeshift shelters nearby. Last Sunday they were picking olives as farmhands.

“My daughter wanted to be a doctor; my son should be preparing for his university exams. But instead they are working with me in the fields,” he says.

As they harvest, they turn their eyes to the mountaintop home they were forced to flee. Just a mile away, it is always within sight, but out of reach.

“If you stay, your children’s lives are in danger, and if you leave, you lose a piece of your identity and your future,” Mr. Kaabneh says. “Your lives or your land. This is the choice we all face.”

Can team Biden avoid a one-term presidency?

Poll after poll shows that President Joe Biden could be in trouble in 2024. And things seem to be trending in the wrong direction for him. But as more people start to tune in to the race, things will undoubtedly change. The question is, in which direction?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

On paper, President Joe Biden’s reelection prospects look highly uncertain.

Even among Democrats, a majority (58%) say they want other candidates to enter the 2024 presidential race. At best, President Biden is in a dead heat with former President Donald Trump, the likely Republican nominee.

Under normal circumstances, a sitting U.S. president would have an advantage in a reelection race. History shows that most incumbents who try for another term win. But these are not normal times. Mr. Biden, now 81, is the oldest American president in history – a negative to voters of both parties. The economy is still recovering from the pandemic, and the rate of inflation, while declining, remains above normal. Two wars are raging abroad.

At home, Mr. Trump is deploying the language of autocrats, critics say, as his allies reportedly plan for a second term that could blow away the conventions of democratic rule.

In many ways, it’s shaping up to be an election year like no other, but in a fundamental way, it’s utterly typical: The state of the economy, and voter perceptions of it, could well determine the outcome.

“It’s the single biggest challenge for the administration,” says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake.

Can team Biden avoid a one-term presidency?

There’s still time.

That’s the message from Democratic strategists to their party’s hand-wringers, following a series of polls that show former President Donald Trump beating the incumbent in a 2024 rematch.

On paper, President Joe Biden’s reelection prospects do look highly uncertain, if not outright daunting. Even among Democrats, a majority (58%) say they want other candidates to enter the 2024 presidential race. At best, President Biden is in a dead heat with former President Trump, the likely Republican nominee.

For those who believe a second Trump term is a “break the glass” moment – an emergency for the future of American democracy – it’s time to pull out all the stops.

But with just under a year to go until the 2024 presidential election, most Americans haven’t fully tuned in. And therein lies hope for both Democrats and Republicans.

Under normal circumstances, a sitting U.S. president would have an advantage in a reelection race. History shows that most incumbents who try for another term win. But these are not normal times. Mr. Biden, who marked his 81st birthday today, is the oldest American president in history – a negative to voters of both parties. The economy is still recovering from the pandemic, and the rate of inflation, while declining, remains above normal. Two wars are raging abroad, with major U.S. interests at stake and no end in sight.

At home, Mr. Trump is deploying the language of autocrats, critics say, as his allies reportedly plan for a second term that could blow away the conventions of democratic rule.

In many ways, it’s shaping up to be an election year like no other, but in a fundamental way, it’s utterly typical: The state of the economy, and voter perceptions of it, could well determine the outcome.

“It’s the single biggest challenge for the administration,” says Democratic pollster Celinda Lake, who worked on the 2020 Biden campaign.

And even though the economy is improving, and has avoided (so far) a widely expected recession, many Americans aren’t feeling it: Grocery prices are at record highs, and “people are reminded of that daily,” says Ms. Lake, who conducts weekly focus groups. “You can’t argue with people about their real, lived experience.”

What’s more, she says, unlike with past inflationary periods, consumers have an unrealistic expectation that prices should go back to where they were before factors including pandemic spending by the government pushed them up.

The president is losing traction among Black, Hispanic, and young voters, all key constituencies. Among voters between the ages of 18 and 34, fully 70% disapprove of Mr. Biden’s handling of the Israel-Hamas war, according to a new NBC News poll. Among Democrats overall, Mr. Biden’s job approval has plummeted into the 70s in the Gallup poll, a record low for his presidency, attributed to his unequivocal support for Israel in the war.

Polls also consistently show Mr. Biden trailing Mr. Trump in voter trust on immigration, national security, and foreign policy. And while the president leads his likely adversary on abortion rights and handling of democracy, those issues have less overall salience with a larger, presidential-year electorate.

Mr. Biden, too, faces multiple third-party challengers who, in theory, could siphon away enough votes to cost him key battleground states, a phenomenon that contributed to Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s loss to Mr. Trump in 2016.

So, is Mr. Biden headed the way of the first President Bush and former Presidents Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford – and into the nation’s second straight one-term presidency?

Not necessarily, historians say. It’s far too soon to draw conclusions from the early polls; many voters have yet to focus on the election. Furthermore, bad early polls can be useful in flagging weaknesses in a campaign and suggest ways to retool, as Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama discovered on their way to second terms.

In fact, Mr. Biden – who served as vice president under President Obama – could be forgiven for having déjà vu. At this point in his first term, Mr. Obama’s job approval ratings in Gallup polls languished in the low 40s, not far above where Mr. Biden’s overall public approval stands now.

That’s not to suggest Mr. Biden has the performative skills of his more charismatic former boss – or of Mr. Trump. And in that regard, says presidential scholar William Howell, the angst Democrats are feeling over polls is justified.

“There’s Biden’s age, but more broadly, he doesn’t have a core base of enthusiasm within the party in the way Trump decidedly does,” says Professor Howell, director of the Center for Effective Government at the University of Chicago.

And that, in turn, fuels Democratic anxiety over what some see as the biggest issue at stake in 2024: the trajectory of American democracy.

“I do believe that that very much is on the ballot,” Professor Howell says. “But I’m not confident that that, as a campaign message, is the ticket for Biden to get reelected. Which leads to a kind of strange dissonance: The thing that matters most may be the thing that’s talked about the least.”

For now Ms. Lake, the Democratic strategist, is focused on the nuts and bolts of why Mr. Biden is struggling in polls today and how he breaks out of that rut.

“Ultimately, Joe Biden will get more credit for his accomplishments when there’s a contrast, and he will also unite and energize Democrats more,” Ms. Lake says. “There’s nothing more focusing than Donald Trump in his element, like when he’s calling people vermin on Veterans Day. That really bothers people, and really bothers women.”

The best issue for Mr. Biden and Democrats overall, polls show, will be abortion. The 2022 Supreme Court overturning of Roe v. Wade, with three Trump appointees voting in the majority to eliminate a nationwide right to the procedure, will motivate key constituencies, including suburban women, as will no other issue.

Buttressed by abortion, Democrats overperformed in off-year elections earlier this month. In Ohio, a ballot measure to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution passed easily, echoing results in other red and purple states. Advocates in several states – including Nevada and Arizona, both battlegrounds – are trying to put abortion referendums on ballots next year.

But in a presidential year, turnout will be higher than in off-year elections – and if Mr. Trump is on the ballot, that will goose turnout on both sides.

David Pepper, former chair of the Ohio Democratic Party, says Mr. Biden already has a good economic story to tell; he and his surrogates just need to tell it.

“They’ve got work to do, but Joe Biden actually has a decent record to run on, if they’re able to communicate it well,” Mr. Pepper says. “What he inherited versus where we are is quite strong.”

Just watch Ohio Republicans in statewide office talk about the Ohio economy, he says. “They run around every day talking about how great it is. And it’s clearly not about Ohio; it’s a national recovery.”

Mr. Pepper also thinks “Scranton Joe” – the Mr. Biden who loves to travel to small cities like his Pennsylvania hometown, and talk to voters – can be effective in building up the public’s assessment of the economy.

“He can show up in Mansfield, Ohio, and say, ‘I know what’s happening in this town. And when we talk about infrastructure, we’re not just talking about the billion-dollar bridge in Cincinnati, which gets all the attention. We’re talking about the five-figure project that could make a difference to your town that’s been struggling too long,’” Mr. Pepper says.

But even if “It’s the economy, stupid” still reigns as the ultimate campaign mantra, other elements will factor in, says American University historian Allan Lichtman, who uses “13 keys” to predict U.S. presidential elections.

A year out, it’s too early to forecast 2024. And while it might seem that a Biden-Trump race features two incumbents, it will still be a referendum on the sitting president, Professor Lichtman says.

“This election will turn on governance more than anything else,” he says, adding a caveat: “Historical patterns are strong but not necessarily invincible. And we do have something quite unprecedented, not just a former president versus a current – but a former president who faces 91 felony counts, who could be convicted and sentenced to prison before the general election. Who knows how that might shake things up?”

The Climate Generation

On tides of climate change, adaptability buoys hope

In Bangladesh, where Himalayan waters flow into the world’s largest delta, climate disruption is already causing mass migration. But a deeply ingrained culture of adaptation is also opening an opportunity for one girl and others like her. Bangladesh’s future depends on them seizing it.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 16 Min. )

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

When 11-year-old Lamia Akter’s teacher asks students what climate change is, small voices blurt out: “Floods! “Cyclones!” But – as one of the estimated 2,000 climate migrants arriving in Dhaka, Bangladesh, every day – she knows the answer better than anyone. She was forced to relocate to this capital city when her family home in Kishoreganj was washed away last year.

Water is never in balance in Bangladesh, situated on the world’s largest delta. Climate change intensifies the destructive forces of water, making children among the world’s most vulnerable.

But Lamia is a climate adapter, a member of what the Monitor, in this global report, is calling the Climate Generation: those born since 1989, when the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child was adopted and when climate change became a familiar phrase in global consciousness. Here in Bangladesh, she’s part of a new national narrative of climate adaptation in facing the effects of climate change.

Adaptability – everything from rainwater collection to better education – affects where children live, if they have to work, and when they’ll marry.

Mitigation was the traditional solution but now, says Asif Saleh, the executive director of the nongovernmental organization BRAC, “we are seeing that that’s irrelevant, that even if you do mitigation, you will need to continue to do adaptation because changes are happening on the ground.”

On tides of climate change, adaptability buoys hope

Water is never in balance in Bangladesh, where rivers flowing from the Himalayas converge in the world’s largest delta. That makes children like 11-year-old Lamia Akter among the world’s most vulnerable in the face of climate change.

But she’s also a climate adapter.

Down an alleyway no wider than 3 feet, in one of Dhaka’s thousands of teeming informal settlements, is a bright little schoolroom filled with tiny wooden tables.

When the teacher asks the students – ages 8 to 14 – if they know what climate change is, Lamia is too timid to answer. So she lets other small voices blurt out: “Floods!” “Cyclones!” But – as one of an estimated 2,000 climate migrants arriving in this capital city every day – she knows the answer better than anyone. Her family home on the northern flood plains of Kishoreganj was washed away last year, forcing them to move here.

Now, her mother works in a garment factory; her father, once a rice farmer, drives a rickshaw. Back home, where their view looked onto cultivated paddies, annual monsoon floods are commonplace. But flash floods last year, part of a trend of storms bigger and fiercer than the seasonal norm, wiped away their home – a plight thousands of Bangladeshis face amid Himalayan glacier melt, rising sea levels, river erosion, and more erratic rains.

Life is harder now, explains her mother, Shirin Begum, at their Dhaka home. It’s a sweltering single room of corrugated metal, drab save the meticulous line of bright salwar kameez outfits hanging from ropes strung across the walls.

But climate migration has offered an opportunity to her daughter, too.

“I went to school until grade five, and I felt sorrow that I couldn’t do that for my daughter,” says Ms. Begum.

In her late 20s, Lamia’s mom is a beneficiary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). The human rights treaty’s protections have transformed childhood around the globe; here, they’ve spurred mass enrollment in primary schools.

But by the time Lamia was born in 2012, the effects of a warming planet were already threatening her right to education: The family couldn’t access a boat necessary, amid prolonged flooding, to get Lamia to school. “I often cried about it,” says her mother.

Both Lamia and her mom are part of what the Monitor, in this global report, is calling the Climate Generation: those born since 1989, when the UNCRC was adopted and when climate change became a part of global consciousness. In August, the U.N. Committee on the Rights of the Child acknowledged that global warming threatens to roll back gains brought about by the treaty – and it underscored that children’s human rights include the right to a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. The group of experts placed particular attention on the “disproportionate harm faced by children in disadvantaged situations” – children just like Lamia.

Today Lamia is learning to read and write as part of a collaboration among the government, nongovernmental organizations, and UNICEF to help vulnerable children enter the formal education system. And, in a country lauded for its climate resilience, Lamia as a climate migrant is part of a generation whose lives demonstrate the adaptation required to face the crisis.

“Within the climate space, we see a big gap ... because for a long time the dialogue has been that if you’re focused on [doing] mitigation well, you do not need to do adaptation,” says Asif Saleh, executive director of the NGO BRAC. “But we are seeing that that’s irrelevant [now], that even if you do mitigation, you will need to continue to do adaptation because changes are happening on the ground.

“Bangladeshis are adapters, and they will continue to adapt,” says Mr. Saleh, whose organization leads climate adaptation models throughout Bangladesh, “and I do think young people will lead in terms of coming up with good adaptive solutions.”

From entering new schools to forging new awareness in cities like Mongla, which calls itself Bangladesh’s first “climate resilient migrant-friendly town,” this generation is securing its rights even as it comes to terms with how adaptability will be required. It will affect everything from where they’ll live and how long they can study, to when they’ll go to work and when they’ll marry – especially as girls Lamia’s age are newly vulnerable in the impoverishment of climate migration.

“I want [Lamia] to complete her education and to be whatever she wants to be,” says Ms. Begum.

That, says Lamia, resting her head on her mom’s shoulder, might be a teacher.

Her mother adds, “But I wish we didn’t have climate problems, so we’d be at home, so she could have gone to school [there].”

For thousands of years, the easygoing people at the confluence of the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna rivers have lived with raging floods and tropical storms. A warming planet has made those ancient patterns more erratic and intense for today’s 170 million Bangladeshis.

Climate change could prompt the displacement of 216 million people by 2050, estimates the World Bank – and low-lying Bangladesh and its children are among the world’s most vulnerable to climate-related extremes. By then, the bank concludes, a third of Bangladesh’s agricultural gross domestic product may be lost due to climate variability and extreme events. Today about 3% of the population has been uprooted – but food and water scarcity and rising sea levels are expected to drive that to 12% within 30 years.

The pressures come across the country – bigger floods in the north from glacier melt, rising seas and salinity levels in the southern coastal zone, increased river erosion along the web of 700 waterways that crisscross this nation.

This is forcing thousands of people to Dhaka, one of the fastest-growing megacities in the world, by bus, boat, and bicycle, and on foot. And the Dhaka-based International Centre for Climate Change and Development (ICCCAD) estimates this rapid urbanization is going to get “bigger and bigger.”

All of this can feel theoretical in much of the world. But it’s visible in real time in Bangladesh by simply walking to the eroding edge of a riverbank – like the one that is 12-year-old Jahidul Bepari’s front yard. That’s where he learned to fear cracks in the earth.

Here, in the district of Sarankhola, two hours southeast of the closest sizable city, Mongla, the land along the rivers and channels is in a constant state of increasingly rapid transformation.

Sometimes the impact is stunningly immediate: In 2007, Cyclone Sidr swallowed thousands of homes here, leaving clusters of hyacinths floating in their places today and driving many residents to Mongla. Other times the impact of climate change, on river erosion for example, is a painful, slow-motion process for those on the literal edge, like Jahidul.

The cracking earth, he says, “means something bad is going to happen.” River erosion has caused his family to move twice in his young life – each time rebuilding their simple home with wood and scraps of tin weighted down with bricks, moving each time with the riverbank as it receded. And each time, they got poorer.

His mother points to the site of their first home – now washed away into the middle of the Baleshwar River. The last time his home was swept away, three years ago, he was 9 years old. He remembers the pitch black of night, before bedtime, when floodwater swept into the house and nearly drowned them. “I have trouble sleeping still,” he says.

The family has no more resources to keep Jahidul in school, so he stopped studying after fifth grade, joining his family in fishing the river here that gives them everything – and can take it all away. One day, they know with almost certainty, they will have to leave.

That’s why the government, along with national and international NGOs and the ICCCAD, is trying to forge a new narrative in nearby Mongla – that climate migration itself can be seen as an act of adaptation, a proactive choice in the face of reality instead of a traumatic uprooting that marginalizes the family and child.

Creating that narrative of adaptation in Mongla involves engineering a new “social-cultural construct” – a new mindset foundation, as Saleemul Huq, the late director of the ICCCAD, put it in a Monitor interview earlier this year. And the younger generation is where that can take root most solidly, he emphasized.

Mongla is managing that thought shift in small and large ways. The city aims to attract climate migrants, seeing them as a feeder of the economy, rather than a drag on it. And it announces its intentions boldly, with hot-pink rain-collecting tanks. They cheerfully punctuate the landscape in a visual advertisement of the effort to sustainably provide clean water to the growing population. Locals joke that their port city is “turning pink” in the effort to be a model of adaptability as the nation’s first climate-resilient, migrant-friendly town.

The tanks are as much PR as a solution to the rising salinity levels of fresh water. Making the nation’s population both aware of the challenge to source enough drinking water and able to adapt to it is the first part of a strategy to relieve climate migration pressure on the nation – the world’s eighth-most populated in an area about the size of Iowa.

A community that has adapted to climate-related pressures, the reasoning goes, will welcome new migrants without a scarcity mindset taking over, explained Dr. Huq, who died unexpectedly just before press time.

And young people are key to this, he said. One idea floated here is to offer scholarships to schoolchildren to incentivize families to move here, relying on young people to be the natural ambassadors of coexistence.

Forging a “migrant-friendly” city is a top-down and bottom-up approach, Mongla Mayor Sheikh Abdur Rahman explains. The job of the city, at the edge of the Sundarbans, a UNESCO-protected mangrove forest, is to create jobs and protect them in the face of climate change.

Mongla’s population has expanded to 150,000 alongside the industry that has grown here since a port was built in the 1950s. Thousands cross the Pashur channel daily on flat wooden boats by which commuters reach jobs in garment factories in the business export zone. The city has completed infrastructure like flood-protection embankments, floodgates, and better drainage systems as it faces increasing floods.

The grassroots water management efforts are led by a constellation of NGOs, academics, agencies, and donors fostering climate awareness and adaptive behavior so families can stay put.

On a recent afternoon, students at the all-girls Shiria Begum secondary school line up for water at its pink tank installed by BRAC. Without rainwater harvesting, the water that families collect in clay pots at their homes often dries out in the dry season. Then they’re forced to buy pond water, which student Mafiya Khatun says, scrunching her nose, is “disgusting.”

An eighth grader, Mafiya learned in science class that, by 2050, a fifth of Bangladesh will be underwater. “That scares me,” she says. “It makes me sad.”

That pink tank at Mafiya’s school is one of 26 set up at public centers and over 5,000 more at homes across Mongla in the past year. BRAC aims to serve 67,000 individuals in Mongla – up from 12,000 today – by the end of 2024.

The work is also that of changing mindsets. BRAC and the Global Center on Adaptation are establishing “locally led adaptation” committees in the 20 most vulnerable communities of Mongla. Each committee, composed of 60% women, also has one youth representative to help identify the community’s needs and drive change.

At an informal settlement of 60 homes at the edge of the Pashur River, committee youth member Fahima Begum says her community chose to excavate an old pond about the size of a soccer field. The project is not for aquaculture, an industry that has increased salinity problems amid the labyrinth of ponds and channels of Mongla, but so residents can collect enough rainwater for household cleaning.

They’ve also recently installed a rainwater harvesting system that will have the biggest impact on women and girls, she says. Doctors are telling women about studies suggesting that salinity causes reproductive problems, Ms. Begum says matter-of-factly. And high schooler Fatema Akhter says she sometimes has to walk 3 miles to access clean water.

Ms. Begum, who is 24, sees young people like herself as key to the changes underway in her community: “Young people are able to accept change more easily than elders,” she says, “and we can communicate changes faster.”

Indeed, pupils at Mafiya’s school already demonstrate adaptation, says Khadeja Parvin, who teaches the chapter on climate change impact. If their parents are learning new techniques, such as how to store rainwater, for their children it’s simply the way of doing things now, explains Ms. Parvin – at age 34, a member of her students’ generation.

“It’s easy for them to understand because they are living it every day,” she says. “They can adapt because they understand the facts.”

If Lamia or Jahidul were to become her peers in Mongla, Mafiya says she’d welcome them.

Many of the climate migrants who have found their way to Dhaka have to fight for their right to a full childhood – one in which they can study as long as they want, without having to supplement family income.

According to UNICEF, net primary school attendance shot up from 65% in 1990 – when Bangladesh ratified the UNCRC – to 86% in 2019. It’s one of the clearest gains in children’s well-being in Bangladesh – but it’s also the one most clearly threatened by climate change, says Emma Brigham, deputy representative for UNICEF Bangladesh.

The year 1990 also marks the first time that the impact of climate change on human migration was identified in the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – the world’s guidance for governmental climate policies. The panel suggested that the greatest single impact of climate change could be forced migration – with millions of people displaced by shoreline erosion, coastal flooding, and agricultural disruption. And many around the world are concerned that today’s climate migration – to or from anywhere – is making children’s lives more precarious in the face of poverty and the ongoing fallout from the pandemic.

At a protection center in a neighborhood of Dhaka known as “burnt slum” that looks out onto an old landfill, children, including some newly arrived migrants, are singing a song on a recent day. Begun in 2021, hubs like this one are raising awareness of human rights, building community bonds, and using government databases that administrators believe are preventing hundreds of cases of child marriage and illegal or hazardous child labor each month, UNICEF says.

Of 35 children who eat meals and get lessons here, 27 have jobs such as collecting garbage or working in tile or garment factories, says Shaikh Reshma, child rights facilitator for the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, which runs the center with support from UNICEF. She says that for families, having children work “is a choice of impossible choices to be made.”

Climate change and migration intensify these choices of how to maintain livelihoods, says UNICEF’s Ms. Brigham. “That’s where a coping mechanism such as marrying your daughter off becomes a requirement. Climate vulnerability areas ... overlay very clearly with higher rates of child marriage.”

The displacement of children is what spurred the activism of 25-year-old Farzana Faruk Jhumu, who since 2022 has been a UNICEF Bangladesh youth advocate.

She never intended to be a climate activist. Before the pandemic, she was brainstorming with her siblings and friends about how to make a difference in their community. In 2019, full of young idealism, they decided to start an informal “classroom” in an informal settlement, 10 minutes from their home.

Three months in, a new girl appeared – a climate migrant just like Lamia, who lives in the same part of Dhaka. She told them she’d just arrived from the coastal south because a flood forced her family from their home. Ms. Jhumu started noticing a trend, and how, for children, climate migration was exacerbating the many problems that inspired her to help them in the first place.

“Everybody knows that climate change exists. We see it every day, every month, every year,” she says. “But that idea that it’s not all about planting trees or plastic pollution, that is what I learned. ... We need to talk about intersectionality, how women [and children] are more impacted.”

Today she is one of the country’s most recognized young climate activists, and she travels to climate conferences around the globe as a youth advocate. Her message centers on her country’s resilience – particularly that of its children, poised to face the crisis because of the rights they’ve garnered.

When the gong signals the end of the school day, Mafiya heads to an after-school club, taking a treacherous hopscotch on bricks scattered over slick mud. There she meets up with Muntarin Jaman, a fellow eighth grader, and 19-year-old Sanjida Akhter. The club aims to teach Bangladeshi children about key issues they confront in daily life. It introduces awareness of climate science and legal rights around dangerous and exploitative child labor and child marriage. And it includes such subjects as the etiquette of looking people in the eye to make social interaction more civil and the hygiene of washing hands often.

They’re best friends. They paint their hands with henna and write Bangla lyrics in the folk style of rural scroll narrative music to express their young thoughts. They don’t have cellphones, but sometimes they borrow their teacher’s to listen to Bollywood music and make up dance routines.

A pouring rain thunders off the tin roof that covers the one-room children’s center run by the NGO CODEC, which works on community development across coastal Bangladesh. Inside, about two dozen students perform a song they penned for last year’s World Environment Day.

“Lots of meetings and seminars, everyone is busy. Giving speeches on this World Environment Day is so easy, but who thinks of doing something practical?” a girl belts before all the children join in the refrain. “Let’s come, join, and do something for the environment!”

It comes out off-key: Muntarin puts her head, embarrassed, on Mafiya’s shoulder, and the two giggle.

They’re learning about how climate change intersects with their lives as a magnifier of the day-to-day problems closest to their hearts. Climate change intensifies the rain that falls through the roof on Sanjida’s head while she sleeps; it’s the reason they drink rainwater; it animates their seriousness about cyclone protocols.

Sanjida explains that some women in her community refuse to go to the cyclone shelter next to their house – the local primary school – because of traditional beliefs about dying anywhere but on their father’s or husband’s land.

But instead, some of those women are beginning to embrace the life-or-death importance of heading to a safe shelter. This includes learning how the nation’s advance warning system works and how to prepare for a cyclone – including tying up their hair, gathering medications, and putting valuables in a barrel and burying them.

Mafiya boasts proudly that she convinced her family – including her grandmother – to head to the shelter for the first time when a cyclone was forecast in May.

They’ve also learned about the intersections of their rights and climate change, particularly the domino effect it has on very personal aspects of their lives, such as when they marry.

UNICEF

Sanjida’s two elder sisters were married at 14 and 16. A few years ago, her father, who works as a day laborer wherever he can, brought up the subject of her own marriage. She says that pressure is in part because the family can’t grow its own food in the saline earth. Still, she told her parents she wasn’t interested.

“They haven’t brought it up again for now,” says Sanjida, who makes sure to add to all listening that, in fact, she never wants to get married.

“When children marry early, they face complications during pregnancy; their education gets hampered; they are deprived of their childhood and the love of their families,” says Mafiya, her serious words incongruent with her schoolgirl giggle. “Climate change is related because it makes people poor, and girls are seen as one more burden in the house.”

While it’s not possible statistically to show a direct link between climate change and child marriage at the societal level, experts increasingly try to draw one at the grassroots. A recent study published in the journal International Social Work linked droughts, floods, and other extreme weather events to early and forced marriages. In Bangladesh, marriage increased by 50% among girls between the ages of 11 and 14 in years with heat waves, researchers found.

The prevalence of marriage here among girls under age 18 stands at 51%, one of the highest rates in the world. But it was over 80% in 1990, when Bangladesh ratified the UNCRC. That means that, if these girls had been born before then, they very well might be married right now, says Mafiya. Her grandmother married at age 12. Her stepmother, Nipu Begum, who is raising her, married at 15.

One day after school, her stepmom concedes that Mafiya’s education is not her top concern. Her priorities are accessing clean drinking water to prevent her five children, the youngest still a baby, from getting diarrhea, waterborne illnesses, and the reproductive problems believed to be connected to contaminated water.

Still, like Lamia’s mother in a one-room home north in Dhaka, she supports Mafiya’s ideas. “I want her to do whatever it takes, however long she wants to study, and whatever is good for her future.”

To Mafiya, a good future means having enough food, clothes, education, health, and rights to participate in decision-making – all in a clean and safe environment, ideally right here in Mongla.

In other words, she wants all the rights guaranteed to her under the UNCRC. For that, she must be a climate adapter, and she welcomes others to adapt alongside her community in Mongla. Her reasoning is simple: “It would be saving lives.”

After all, that’s her ultimate dream, at the heart of her idea of progress.

Mafiya wants to become a doctor. So does Muntarin. Sanjida wants to become a nurse. They are the youngest cohort of the Climate Generation.

Argentina’s president-elect promises drastic change

What happens when you mix repeated economic crises with political coalitions that have been in power for decades? In Argentina, the result is a new president-elect short on experience but bursting with bold ideas. Can he really shake up Argentina as promised?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Max Klaver Contributor

Far-right former TV pundit Javier Milei is Argentina’s new president-elect after winning nearly 56% of the vote in Sunday’s runoff election. His victory underscores a broad rejection of the Peronist movement, a political coalition rooted in the working class that took shape in the 1940s, as well as a desire for drastic political and economic change.

Argentina clocked in with 143% annual inflation this year, the highest in nearly three decades, and unemployment and poverty are on the rise.

“Those factors contributed to the population’s disgust and exhaustion with traditional politics and gave Milei visibility,” says Paola Zuban, a pollster with Zuban Córdoba y Asociados.

Mr. Milei is promising to upend politics as Argentina knows it. That may be tempered by the fact that he faces a divided Congress, where Peronists and their allies hold a plurality in both the upper and lower houses. Meanwhile late-in-the-game endorsements from other opposition coalitions could sideline some of his flashier pledges, such as trading in the peso for the U.S. dollar.

If he’s going to succeed, “he’ll have to turn to others,” says political scientist Pablo Touzon.

Argentina’s president-elect promises drastic change

Argentina elected far-right libertarian Javier Milei as its next president, underscoring deep-seated discontent with the country’s politics and economy, and a desire for drastic change – even if it comes at a cost.

The economist and former TV pundit burst onto the political scene just two years ago with a promise to implement radical free-market policies. Pledges to destroy Argentina’s political elite and assertions that the “caste trembles” have been his go-to rallying cries, often punctuated by images of a rumbling chain saw.

Having won nearly 56% of the vote, he is now Argentina’s president-elect.

Mr. Milei bested the ruling Peronist coalition’s candidate, Minister of Economy Sergio Massa, by nearly 12 percentage points. The result shocked many after Mr. Massa won the most votes in last month’s first-round election.

Mr. Milei’s performance highlights popular frustration with the status quo in Argentina, where inflation reached its highest point in nearly three decades and 2 in 5 people now live in poverty. He’s committed to shrinking the size of the government, “blowing up” the central bank, ditching the peso in favor of the U.S. dollar, and upending Argentina’s foreign policy.

“The changes the country needs are drastic,” Mr. Milei said in his victory speech last night. “There is no room for gradualism, for tepid half-measures.”

The stakes are high for him to deliver on his promises. Social tensions are nearing a boiling point as money becomes worth less each month in Argentina, and observers say Mr. Milei could face public protests from the moment he takes office Dec. 10. On top of that, pushback from a divided Congress, where the Peronists and their allies hold a plurality in both the upper and lower houses, could dampen some of his more extreme plans.

“The holidays, Christmas and New Year’s, are a very sensitive time in Argentina, especially when there’s an economic crisis,” says Paola Zuban, a political scientist and director of Zuban Córdoba y Asociados, a political consultancy. “A Javier Milei government will have to deal with many social movements taking to the streets to protest.”

“The same things”

Mr. Milei’s resounding triumph demonstrates the degree to which he’s successfully captured popular disenchantment with Argentina’s traditional political forces.

Mr. Milei was considered a protest candidate: Many of his supporters don’t agree with his core social and economic stances, but instead with the change he represents. But his ability to appeal to, above all, young men who are desperate for a change in the country’s economic and political situation helped propel the radical outsider to victory.

“Everyone who came before tried the same things, and they didn’t help at all,” says Francisco, a 17-year-old and a first-time voter in Buenos Aires. Standing among a crowd of Mr. Milei’s supporters who chant, “Liberty,” Francisco says he’s not on board with all of Mr. Milei’s policy ideas. But “this man proposes something different for the country, which I think is needed.”

Throughout the campaign, Mr. Milei was able to reach Argentina’s youth through savvy social media campaigns. In a number of viral, expletive-laden videos, he railed against Argentina’s political establishment with often casual, relatable disdain.

The pandemic also played a large role in laying the groundwork for his success, says Ms. Zuban, describing it as having “shattered Argentina’s social fabric.” Those without formal employment, some 45% of the population, saw their earnings evaporate and received little financial support from the state during one of the world’s longest lockdowns.

“They saw how their neighbors [with formal employment] could navigate the situation while they sank into a profound crisis. This caused a significant social rupture,” she says.

Those inequalities, combined with several scandals, confirmed for many that Argentine citizens don’t receive equal treatment, from certain politicians’ flouting the country’s intense lockdowns with impunity, to others’ receiving preferential access to vaccines.

In that context, says Pablo Touzon – a political scientist and founder of Panamá Revista, a political publication – many were drawn to Mr. Milei’s bombastic rhetoric and promises to eradicate what he calls the “political caste.”

For many, Mr. Massa, a career politician, was the embodiment of that caste. His Peronist coalition has ruled Argentina for 16 of the past 20 years. Opposition to the Peronist movement, which dates back nearly 80 years, drew many toward Mr. Milei.

Annual inflation surged to 143% this year, and the peso’s value plummeted. Mr. Massa, who is also the current economy minister, struggled to make a case for why the captain of an economy in such dire straits could also be its savior.

“Those factors contributed to the population’s disgust and exhaustion with traditional politics and gave Milei visibility,” says Ms. Zuban.

Upending business as usual?

Following his win – which drew congratulations from the likes of former U.S. President Donald Trump, X (formerly Twitter) owner Elon Musk, and former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro – Mr. Milei promised an end to “Argentine decadence.”

His extreme rhetoric and policies may be viewed as enticing to some, but they are just as troubling to others.

Outside Mr. Massa’s campaign headquarters, Luis, a local journalist in his 30s, stared blankly at the stage where the Peronist candidate had just given his concession speech. Next to him, a woman and her young daughter, both wrapped in Argentine flags, sat sobbing.

“I am scared. I feel threatened,” says Luis, who asked not to use his full name out of privacy concerns. “[Milei’s] proposals directly attack issues that are central to our identity as a country, issues that are central to our democratic system,” such as support for public education and the unequivocal repudiation of Argentina’s last dictatorship.

Human rights groups, including Argentina’s famous Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, have accused Mr. Milei and his running mate of denying the crimes against humanity perpetrated by Argentina’s 1976-1983 dictatorship.

He’s characterized the military government’s atrocities as a pursuit of national security, and he’s questioned the number of people killed during that period, asserting that it is far fewer than the broadly accepted estimate of 30,000.

Turning to others

Despite his commanding win, Mr. Milei will need to find political accord within the alliance that delivered him the presidency. Some of his high-profile backers from the opposition, such as Patricia Bullrich – who placed third in the first-round presidential vote – have vocally opposed some of his key proposals, including his plan to adopt the U.S. dollar as Argentina’s national currency. Argentina flirted with dollarization in the 1990s, when it pegged the peso to the dollar, though that scheme ended disastrously in 2001 amid a political and economic crisis.

The support Mr. Milei received from Ms. Bullrich and her party after the first-round vote boosted his image, says Ms. Zuban, lending him “a certain degree of sanity,” in the eyes of skeptical voters unhappy with Peronism.

“Milei will face a governance problem,” says Mr. Touzon, the political scientist, emphasizing that the president-elect will need to rely on the party infrastructure of his more politically mainstream allies.

“I don’t think the libertarian space [in Argentina] has enough people to fill even two government ministries,” Mr. Touzon says. If he’s going to succeed, “he’ll have to turn to others.”

Points of Progress

‘We’re sorry,’ and other reversals from California to Colombia

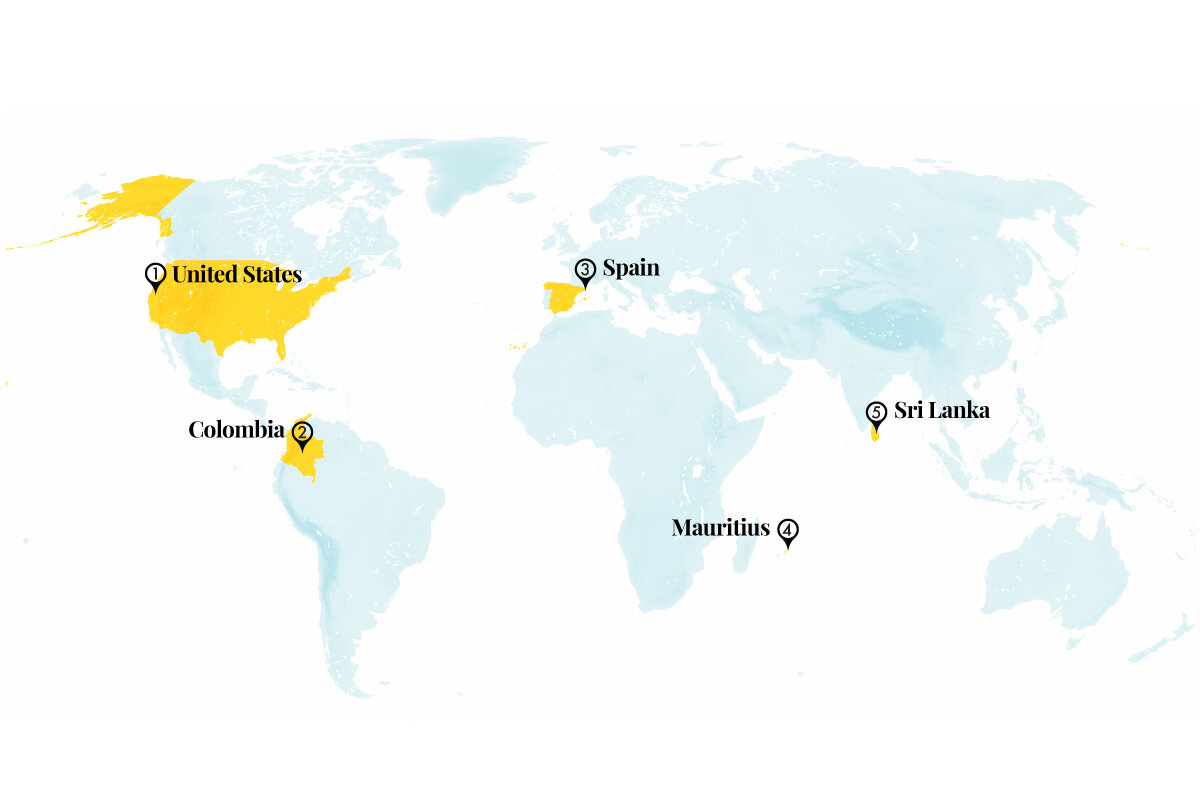

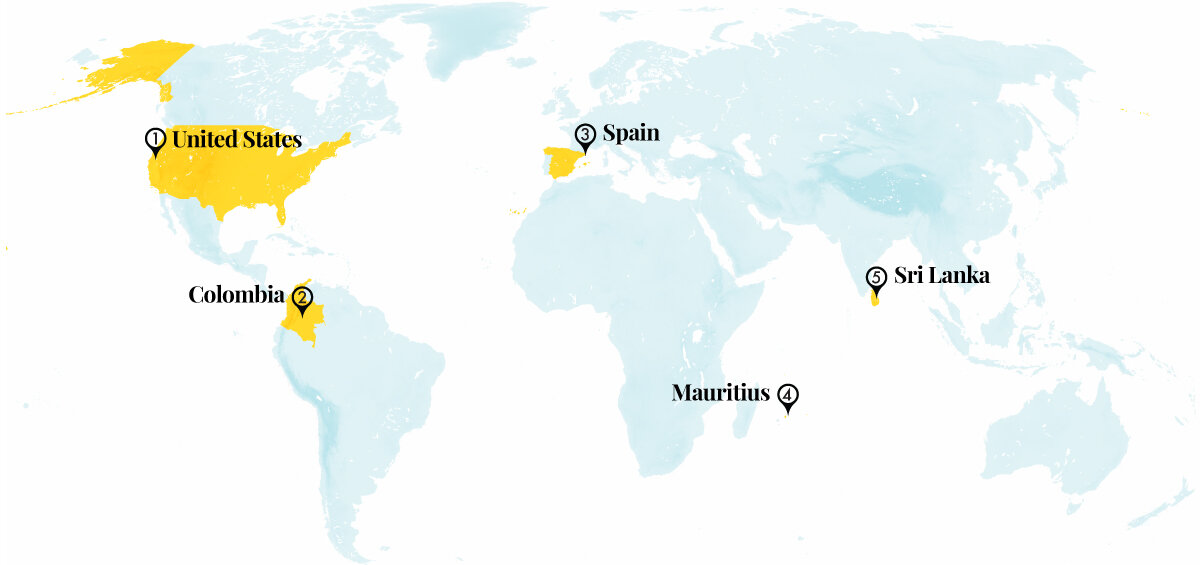

Our weekly roundup of progress around the globe sees a measure of justice for a Native tribe in California, people killed by the military in Colombia, and the LGBTQ+ community in Mauritius. There’s also a boost for drought resistance in Sri Lanka, and a Barcelona “bicycle bus” for kids.

‘We’re sorry,’ and other reversals from California to Colombia

1. United States

The Winnemem Wintu tribe purchased 1,080 acres of its ancestral land in Northern California with $2 million in donations, a win for the Indigenous “Land Back” movement. The land is near the tribe’s existing 42-acre village and Bear Mountain in Siskiyou County.

After construction of the Shasta Dam in the 1940s, Winnemem villages and burial grounds were flooded, further displacing the tribe. Chinook salmon, sacred to the Winnemem, declined as the dam disrupted their breeding patterns. To raise awareness for the endangered salmon and promote Indigenous stewardship, since 2016 the tribe has held an annual 300-mile prayer journey, worked on creating passages for salmon to avoid the dam, and collaborated with other Indigenous groups and U.S. agencies to scale up conservation efforts.

The Winnemem Wintu purchased the land through the tribe-run nonprofit Sawalmem, whose church status allows flexibility with land use. The tribe can now build sustainable housing and infrastructure such as solar panels and water runoff systems for its members. “Our purpose is to restore the land [to] the way it’s supposed to be, which means control burns, native plants, all the waterways totally restored,” Michael Preston, executive director of Sawalmem, said.

Sources: Vox, Sierra Club, Bay Nature

2. Colombia

Colombia formally apologized for “false positive” extrajudicial killings by the military during its civil war. A special peace tribunal found that between 2002 and 2008, Colombian soldiers under pressure from superiors killed at least 6,402 civilians and passed them off as rebels killed in combat – creating false evidence that the government was winning the conflict. Though previous administrations have resisted calls to make amends, Defense Minister Iván Velásquez apologized for the murders at a ceremony attended by 19 victims’ relatives. The civilians who died were often from poor communities and lured by the promise of jobs before being executed.

“We’re standing here before the victims, before the Colombian society, before the international community, to say sorry,” Mr. Velásquez said.

Former President Juan Manuel Santos – who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2016 for negotiating a cease-fire with Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas after more than five decades of war – had apologized in 2021 in a closed-door hearing. But some politicians maintain that the killings were isolated and not a systemic problem within the military.

The peace tribunal investigating the “false positive” cases has charged at least three generals for the killings, and more than 700 members of security forces have given evidence so far. Relatives at the ceremony and human rights advocates say they will continue to press for justice.

Sources: BBC, The Associated Press, Al Jazeera

3. Spain

The bicibús (bicycle bus) is getting Barcelona’s children to school safely – and in style. Barcelona is the most car-dense city in the European Union, sometimes making cycling to school unsafe for children. But in a parent-led effort that began two years ago, dozens of children are now cycling to school in a caravan flanked by adults and one police car.

While the bike bus concept is not new, it has grown quickly in Spain’s second-largest city. There are 15 routes throughout Barcelona, in which 700 people a week have participated.

The initiative is popular with kids, and teachers say the children come to school more refreshed and energized. “What I like best about the bicibús is meeting girls and boys I don’t know from other schools,” said Lola, a 4-year-old.

The bicibús is part of a broader movement to make Barcelona safer for children, and advocates have presented a series of proposals to the city, including more cycling lanes and a lower maximum driving speed. Local sustainability transit leaders hosted a bike bus summit last spring for about 30 attendees from Germany, Britain, and the United States, who together committed to expanding the global bike bus network.

Sources: The Guardian, City Lab Barcelona

4. Mauritius

The Supreme Court of Mauritius decriminalized same-sex relations in two landmark decisions. A vestige of 19th-century colonialism, the criminal code against sodomy was found to be discriminatory and unconstitutional.

Justices pointed to similar international court decisions, from Belize to South Africa, that have struck down sodomy laws, and they said that “the Constitution is a living document and must be given a generous and purposive interpretation.”

Advocates have cheered the decision, which defies a tide of African states that have proposed or passed stringent anti-homosexuality laws, such as Uganda.

“There is still a lot to do,” said Jean-Daniel Wong, who manages the largest LGBTQ+ advocacy group in the country. “But ... we have faith in our public institutions.”

The ruling makes the island nation the 10th African country to decriminalize homosexual relations.

Sources: Human Rights Watch, Reuters

5. Sri Lanka

An ancient water management system is helping Sri Lanka’s farmers weather drought. Devised between the 4th and 13th centuries, the system of small human-made reservoirs and cascades had long allowed communities to capture rainwater runoff for future use and cope with prolonged dry spells. As drought and flood risk increase, the ellangawa is getting renewed attention – and rehabilitation.

A cascade system is formed by building embankments around natural depressions in the ground. Sluice gates and stone gauges control the flow of water, which passes from one “tank” to another through streams in rice paddy fields. Other ecological features, like tree belts planted alongside the tanks, can reduce evaporation and protect communities from flash flooding.

Roughly 14,000 tanks and 1,600 cascades are estimated to still be active throughout the dry zones of the island. In 2017, the Food and Agriculture Organization recognized the ellangawa as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System. A World Bank project begun in 2019 with the government is rehabilitating ellangawa in six provinces, emphasizing the importance of participatory planning for the entire cascade, which affects multiple farmers. Integrating other sustainable practices, such as precision agriculture, is also recommended for increasing productivity of farm land.

Sources: BBC, World Bank

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Argentina as a Latin American bellwether

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

After Argentina’s election yesterday, opposition parties in Latin America have now won 19 of the past 21 presidential ballots. That trend provides a reference point for thinking about the region and the turn that its fourth-most populous country just signaled.

Given the choice between the sitting economic minister of a far-left government and a provocative libertarian backbencher to become Argentina’s next leader, voters opted for the unknown. That fits a pattern. The country has now tacked to the right after years of corruption and economic dysfunction. Yet a desire from voters for honest, effective governance echoes popular aspirations that have also swept a handful of leftists into power elsewhere from Honduras to Brazil in recent years.

“The single most exciting thing in Latin America right now is the strength of democracies,” says Susan Segal, head of the Americas Society Council of the Americas. “Indeed, as we have seen time and again, when governments do not meet expectations, they are replaced in free and fair elections.”

Argentina as a Latin American bellwether

After Argentina’s election yesterday, opposition parties in Latin America have now won 19 of the past 21 presidential ballots. That trend provides a reference point for thinking about the region and the turn that its fourth-most populous country just signaled.

Given the choice between the sitting economic minister of a far-left government and a provocative libertarian backbencher to become Argentina’s next leader, voters opted for the unknown. That fits a pattern. The country has now tacked to the right after years of corruption and economic dysfunction (the inflation rate was 143% on Election Day). Yet a desire from voters for honest, effective governance echoes popular aspirations that have also swept a handful of leftists into power elsewhere from Honduras to Brazil in recent years.

“The single most exciting thing in Latin America right now is the strength of democracies,” Susan Segal, head of the Americas Society Council of the Americas, told Americas Quarterly recently. “Indeed, as we have seen time and again, when governments do not meet expectations, they are replaced in free and fair elections.”

The election on Sunday, a runoff between Sergio Massa, the ruling party candidate, and Javier Milei, the leader of a nascent fringe party, underscored the durability of Argentina’s democracy 40 years after the end of a brutal military dictatorship. One sign of that was reflected in Mr. Massa’s concession. When he cast his ballot earlier in the day, he spoke of a future of “goodwill, intelligence and capability but above all, dialogue and the necessary consensus.” He stuck to that hours later, offering in defeat “a message of coexistence, dialogue and respect for peace.”

Mr. Milei has prescribed major reforms to pull Argentina – an oil producer and food exporter – out of negative economic growth with a free-market approach. His proposals to dismantle the central bank, replace the peso with the U.S. dollar, and eliminate scores of government agencies raise eyebrows among many economists. He campaigned without grace, insulting opponents and alleging election fraud without proof after failing to win the first round of voting last month. He has vowed to roll back reproductive rights that took decades for women to achieve.

Even so, he swept 21 of 24 provinces and received a higher percentage of the popular vote than any presidential candidate since 1983. One reason was his appeal for breaking down the political “caste” of the left that has made Argentina one of the most unequal societies in Latin America. In an Americas Society Council of the Americas poll taken last week, voters ranked inflation and corruption as their top concerns. Valeria Brusco, a political science professor at the National University of Córdoba in Argentina, likened the results to “the voice of the ones that are never heard,” in an interview today with Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

During the campaign, the moderating effects of democracy could be seen in the alliances that Mr. Milei forged with more centrist conservatives – including former President Mauricio Macri. Once in office, the president-elect will also need to build coalitions to pass legislation.

The vote, Mr. Macri said, ushers in an opportunity for restoring shared confidence. Mr. Milei “knew how to listen to the voice” of young and impoverished voters, he said. Now, the new government “will need support, trust and patience from all of us.” If set on those values, Argentina will add momentum to a region’s deepening embrace of democratic ideals.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Wholehearted gratitude

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Jenny Sawyer

When we’re willing to look beyond the surface and consider with thankfulness that God, good, is truly supreme, progress and healing naturally follow.

Wholehearted gratitude

It wasn’t an official day of Thanksgiving, but thanksgiving was a profound part of what happened that day. There were thousands in need of food, to which they were without ready access. To Jesus’ disciples, the meager fare available – some bread and a few fish – wasn’t even enough to give gratitude for in the face of such lack.

But for Jesus, thanksgiving was the natural response – not because he was an optimist but because he saw something others didn’t. He saw God’s goodness as present reality, and supply enough for everyone as the natural outcome of this clear spiritual vision. And his gratitude wasn’t in vain: Everyone was fed, with plenty left over (see John 6:1-13).

As we confront the things in our lives and in the world that are in need of healing, are we going to look at what we have with halfhearted gratitude – or none at all? Or are we going to turn to the big-picture gratitude that starts with God and feels a deep and abiding trust that, beyond what the eye can see, good is the power, the true substance of our lives, and the only reality now?

That last option might be difficult, if not impossible, to accept if it were dependent on us to muster up gratitude in the face of looming problems. But we are never working alone. The same Christ that animated Jesus and suffused his healing prayers with power also animates and empowers our prayers today.

Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered the Science of Christ, explained that Christ is “the true idea voicing good, the divine message from God to men speaking to the human consciousness.” This voice of good is powerful because it is the voice of Truth; it reveals what’s real. And it does this by “dispelling the illusions of the senses” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 332) – by showing mortality and its limitations to be a farce, and the infinitude and harmony of God, Spirit, to be the truth of being.

If we’re feeling as though our gratitude hinges on what we presently see or what might happen, that single phrase, “dispelling the illusions of the senses,” is one to reconsider. What would stand in the way of our own deep trust and heartfelt rejoicing – the kind that Jesus expressed? The lie that says that the five physical senses reign supreme; that what we see, hear, and experience is the end of the story; or that we aren’t capable of challenging it. But the ever-active Christ is present to awaken us to God’s supremacy and the spiritual reality, harmonious and good.

I felt the touch of Christ this year when two friends and I committed to praying regularly about climate-related issues. Though I felt inspired and, at times, even expectant of good, I was surprised by my ongoing reluctance to acknowledge any signs of progress, no matter how bona fide. I was missing the promise of the good already present by being so wrapped up in the overwhelming magnitude of the problem.

One day, though, the word “gratitude” came as I prayed, and I realized I needed to wholeheartedly consent to the truth of God’s sustaining care for His creation. This care is a constant. I felt a divine power spiritualizing my perspective and destroying my fear, and I was able to yield to a spiritual sense of creation as the present reality. What flooded in after that was a different kind of gratitude: wholehearted rather than conditional.

While climate change is an issue I’ve continued to pray about since then, it has been from a surer basis. And when I’ve seen reports on positive climate-related developments, I’ve felt more convinced that these solutions represent an infinite range of possibilities for progress.

The world needs our spiritual-evidence-based gratitude. It needs our hearts overflowing with a love for God and all that God is and does. And it needs our being humble enough to keep consenting to the spiritual facts we learn in Christian Science – facts that lift us above the dark images that don’t seem so compelling in the light of what’s really true. This is when we see healing – yes, even with the big things.

Genuine gratitude comes from a spiritual conviction that “all that is made is the work of God, and all is good” (Science and Health, p. 521). And this conviction does indeed lead to very happy – and continuous – thanksgiving.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Nov. 20, 2023, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Blending in

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow, the Monitor’s Sophie Hills visits the last lighthouse keeper in the United States, who is retiring – and could not be happier about it.