- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Can we get everyone an ID?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

IDs were a big deal in the 2020 elections. Should someone need an ID to vote? Do such requirements actually address fraud, or do they depress minority turnout? Lost in the debate was an understanding of how important IDs are for everything from jobs to housing. Can states do better at getting all residents IDs?

It turns out, maybe yes. Colorado has quietly been making headway. Today, we take a look at its innovative mobile program – what benefits it brings and how it could spread. Also, with Israel and Hamas continuing to exchange hostages, we examine the prospects for further progress.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Israel-Hamas: Harder hostage talks still to come

Very soon, the Israelis and Palestinians will run out of comparatively easy things to do to keep the pause in fighting going. How the next phase goes will largely be determined by Israel. Hamas has already achieved its goals and more. For Israel, there is pressure to keep pushing.

Both Israelis and Palestinians have reveled in the results of the temporary cease-fire between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

The initial pause in fighting paved the way for Hamas’ release of 50 civilian Israeli hostages in exchange for Israel’s freeing of 150 Palestinian security prisoners, leading to tearful scenes and jubilation on both sides. On Tuesday, a further 10 Israeli hostages and 30 Palestinian prisoners were released, preserving the agreed-upon 3-1 ratio.

For both sides, the hostage deal has so far involved trading low-hanging fruit – the Israelis freed by Hamas, for example, include 3-year-old twin girls – but analysts say the point is swiftly approaching when the price demanded by one side or the other will become unacceptably high.

“There is a formula for civilians,” says Daniel Levy, president of the U.S./Middle East Project and a former Israeli negotiator. “But ... once it comes to soldiers ... it’s a different formula, so you need to renegotiate that.”

Gershon Baskin, an Israeli peace process adviser and hostage negotiator, says such a negotiation is all the more challenging for Israel, as it simultaneously tries to destroy Hamas militarily. That may be possible to achieve to a degree, he says, but any real solution must reach beyond the current crisis – and current leadership, on both sides – to a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Israel-Hamas: Harder hostage talks still to come

Both Israelis and Palestinians have reveled in the results of the temporary cease-fire between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

In its initial four days, the pause in fighting paved the way for the release of 50 civilian Israeli hostages by Hamas, the militant group that rules Gaza, in exchange for the freeing of 150 Palestinian security prisoners by Israel.

The pause – so far extended by two days through Wednesday – has led to tearful scenes and moments of national elation in Israel, as the daily batches of freed women and children rejoined loved ones after seven weeks of Hamas captivity.

There have also been daily scenes of public jubilation and flying of the green Hamas flag in the occupied West Bank, as Palestinian women and children – some incarcerated for stone-throwing or making knives – were reunited with their families.

On Tuesday, a further 10 Israeli hostages and 30 Palestinian prisoners were released, preserving the agreed-upon 3-1 ratio.

The original cease-fire deal – negotiated by Qatar and shepherded by the United States – paused the Israeli military offensive in Gaza that seeks to “destroy” Hamas following its Oct. 7 attack on Israel, which left 1,200 people dead and 240 captured and shook the Jewish state to its core.

More than 13,000 people have been killed in Gaza, including thousands of children, in the Israeli offensive, and Israeli leaders have vowed to resume the military campaign when the cease-fire expires. High-level talks are continuing in Qatar to extend the pause.

For both sides, the hostage deal has so far involved trading low-hanging fruit – the Israelis freed by Hamas, for example, include 3-year-old twin girls – but analysts say the point is swiftly approaching when the price demanded by one side or the other will become unacceptably high.

“We are running out of road very quickly, even if we get extensions, on this format,” says Daniel Levy, president of the U.S./Middle East Project and a former Israeli negotiator with the Palestinians under former Prime Ministers Ehud Barak and Yitzhak Rabin.

“There is a formula for civilians, for women, children, elderly, and the unwell, and that formula can go a fair bit further,” says Mr. Levy. “But ... once it comes to soldiers and fighting-age males – the majority of whom would be considered reservists – it’s a different formula, so you need to renegotiate that.

“But you also can’t negotiate that out of the context of what is the broader end to this phase of hostilities,” he says. “Let’s put it bluntly: Hamas is not going to give up the soldiers, and not get close to giving up everyone who is not a soldier, until they have a much better prisoner offer on the table – and parameters for ending the overall campaign.

“Why would they [Hamas] give up the last ones, without something that looks like a guarantee that Israel can’t continue doing what it’s doing now indefinitely?” asks Mr. Levy.

For Hamas, Israel’s stated war aims and Hamas’ finite number of hostages to use as bargaining chips will almost certainly raise the price of captured Israeli soldiers. Hamas leaders have spoken of an “all-for-all” exchange of all hostages for the release of all Palestinian prisoners, who now number some 7,200 – a step no Israeli government has ever taken.

And for Israel, waiting for an uncertain outcome of hostage releases means delaying momentum of its war, while under increased pressure from the U.S. and other nations to ease the conflict. It also means ultimately being forced to decide if the bid to destroy Hamas outweighs the lives of scores or more of Israelis who might not yet be free.

Releasing all Palestinians is “really a nonstarter for Israel,” says Gershon Baskin, an Israeli peace process adviser and negotiator who was instrumental in the 2011 release of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit, who spent five years in Hamas captivity. In that deal, more than 1,000 Palestinians were released from prison, including Yahya Sinwar – the current leader of Hamas in Gaza and architect of the Oct. 7 attack.

“The red line over the last eight years has been prisoners with blood on their hands, prisoners who have killed Israelis. And looking back on the Shalit deal, I think there are people in the government who will hold fast to that,” says Mr. Baskin, author of “The Negotiator: Freeing Gilad Schalit From Hamas.”

“Sinwar is going to start by demanding the prisoners who have served the most time, who are prisoners who have killed Israelis,” says Mr. Baskin.

“His gold standard is what he said on the day he was released from prison [in 2011], and has said in every speech since, that he will empty the Israeli prisons. That’s his goal.

“Forget the numbers,” Mr. Baskin says. “If it were 300 prisoners, it would be the same thing. But there are 7,200 prisoners; his goal is to release every single Palestinian prisoner.”

Such a negotiation is all the more challenging for Israel, as it simultaneously tries to destroy Hamas militarily. That war aim may be possible to achieve to a degree, says Mr. Baskin, but any real solution must reach beyond the current crisis – and current leadership, on both sides – to a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“You can’t destroy Hamas as an idea with weapons,” he says. “For that you need a better idea, which has to be a genuine peace process, the establishment of the state of Palestine, the recognition of the state of Palestine, massive international engagement involved in rebuilding Gaza and lifting the Palestinian economy. Forcing Israel to end the occupation.

“Those are the ideas that beat Hamas,” says Mr. Baskin.

“So the question is: Is [the peace process] going to be genuine?” asks Mr. Baskin. “And what are the mechanisms that are going to demonstrate that each side is fighting its own internal insurgents against peace? No one can be sure 100% of peace, but it really depends on the effort being made.”

And getting to that point may depend on the results of Israel’s deeper sweep into Gaza, and of any further cease-fire extensions. After ordering Gaza residents weeks ago to leave the north of the strip for the south for their own safety, Israeli forces have now dropped leaflets on the southern city of Khan Yunis, asking Palestinians to leave again.

“I genuinely don’t think it is so difficult on the Hamas side, because in no small measure they have won already. If this ended tomorrow, [for Hamas] what’s not to like?” says Mr. Levy of the U.S./Middle East Project.

“So I think the real sticking point is on the Israeli side: Under what circumstances, what level of pressure, internal and external, can the Israeli leadership ... be talked down from, ‘We are going to carry on for as long as it takes,’ and going into Khan Yunis and southern Gaza?” asks Mr. Levy.

“I just don’t see how that happens,” he adds, “without some combination of an even stronger domestic push that is led by the families of the missing, that got us to this moment – we should be under no illusions that, if it weren’t for the public pressure of the families, this pause wouldn’t have happened – and of course American pressure that this has to be brought to an end.”

A rough patch on the road to an electric car future

We appear to be nearing the end of a first phase of the electric car era. Those excited about electric vehicles now have them. The next step is to capture those who are curious but have concerns. That’s not going as well as hoped, leaving industry giants at a crossroads.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The likely cars of the future – electric vehicles – face a challenge: Sales aren’t keeping up with expectations. Automakers are pausing to take a new, hard look at the EV market.

Yet the story is more about bumps in the road than about a total breakdown. EV sales are up 50% compared with those of last year, with more than 1 million forecast to be sold this year – a first. But there’s been no breakthrough to make EVs a must-have for the average household. Inventories of unsold cars are building up.

That’s a problem for Tesla, which is producing at such a mass scale that it can afford to cut prices and still make a profit. It’s a disaster for Detroit’s legacy automakers, which are turning out EVs on a much smaller scale and losing money on every one they sell.

The industry has nearly run out of early adopters, people who bought EVs because they loved the technology. Now, it has to convince a new kind of customer who is intrigued by electric cars but more skeptical, especially about their high prices and uncertainty about charging them on the road.

“I’m not doom and gloom,” says auto analyst Stephanie Valdez Streaty. “This is a huge transition, and it’s so complex. It’s a change in lifestyle.”

A rough patch on the road to an electric car future

American flags are flapping. Red, white, and blue banners in the lot urge customers to consider “New car” and “SUV.” And electric vehicles?

Not so much.

“Come back in a few months, and we’ll have a story to tell,” says Dominic Policella, general sales manager at Brighton Ford here in Brighton, Michigan. At least it’s an answer. A General Motors dealer in Livonia won’t return calls. Even Tesla, the leading electric vehicle maker in the United States, ignores repeated requests for interviews.

Why? Sales of EVs aren’t keeping up with expectations. And automakers are pausing to take a new, hard look at the market.

There’s plenty to brag about: EV sales are up 50% compared with those of last year, with more than 1 million forecast to be sold this year – a first. And over a vehicle’s lifetime, battery power significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions, compared with gasoline. But there’s been no breakthrough to make EVs a must-have for the average household. Inventories of unsold cars are building up.

That’s a problem for Tesla, which is producing at such a mass scale that it can afford to cut prices and still maintain profitability. It’s a disaster for Detroit’s legacy automakers, which are turning out EVs on a much smaller scale and losing money on every one they sell. Their conundrum: How much money are they willing to lose to be a part of the future?

“They’re in a big, big squeeze” says Arun Kumar, a partner and managing director in the automotive and industrial practice at AlixPartners, a global consulting firm. To avoid falling behind Tesla and EV-only manufacturers in China, legacy automakers need to accelerate their efforts to reach mass scale in electric cars, even if it means losses for several years.

Instead, GM and Ford are slowing their EV transition. And Stellantis, an EV laggard, is pushing a new kind of hybrid technology rather than a battery-only solution, starting with its Ram pickup trucks. Last month, Ford announced it was delaying its $12 billion investment in battery plants and other EV efforts. GM has pushed back the introduction of several new EVs, including what was supposed to be a relatively low-priced electric version of the Chevrolet Equinox sport utility vehicle.

“Our commitment to an all-EV future is as strong as ever,” GM CEO Mary Barra told analysts last month. But the market is “a bit bumpy,” she added. Mercedes-Benz cited a “brutal” EV market as it announced a 7% drop in earnings for the third quarter.

Part of the challenge lies with the changing consumer base. The industry has nearly run out of early adopters, people who bought EVs because they loved the technology. Now, carmakers have to convince a new kind of customer who is intrigued by electric cars but more skeptical.

In October, nearly 1 in 3 new car buyers was very likely to consider an EV – an all-time high, according to surveys of customers by J.D. Power, a consumer analytics firm. But only a third of those customers ended up going electric. Their biggest concern lies not with the cars themselves but with the prospect of charging them on the road.

The public charging network is not reliable enough and not growing fast enough to keep up with the number of new EVs hitting the road, says Elizabeth Krear, vice president of electric vehicle practice at J.D. Power. One in five charging attempts fails.

The Biden administration along with automakers and even oil companies are pouring in money to grow and upgrade the charging network. Ford, GM, and other companies have signed on to use Tesla’s extensive network of charging stations. But such efforts will take time.

Then there’s the price challenge. EVs generally cost thousands more than their gas-powered versions. Tesla price cuts have brought prices down to the point where premium EVs are now on par with gas-powered counterparts, when measured by total ownership costs, according to J.D. Power. But at the mass market level, gas-powered models are still cheaper.

Government intervention complicates the picture. On the one hand, the federal government is encouraging the transition to battery-powered transportation by offering up to a $7,500 tax credit for purchases of qualifying EVs, and nearly 20 states offer additional tax breaks. On the other hand, it could force the technology on reluctant consumers, sparking a backlash. As things stand now, emission standards under the Biden administration means automakers effectively will be required to ensure that two-thirds of their new car sales are EVs by 2032.

“Silly,” says Ashley Nunes, director for federal policy at the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental research organization based in Oakland, California. “Many of these automakers will effectively be forced to underprice their EVs by offering huge discounts and price cuts just to comply with the standard that the administration has put out. But that is a one-way ticket to bankruptcy.”

Instead, government should incentivize a competition among manufacturers, he says. “We need a space race, if you will, for the cheap electric car – not just an electric car that consumers can buy but an electric car that they want to buy.”

Unforeseen events could change the EV calculus: a battery breakthrough, for example, or a huge hike in gasoline prices. For the moment, though, it looks as though automakers will face years of steady but less-than-spectacular growth in EV sales.

“I’m not doom and gloom,” says Stephanie Valdez Streaty, director of industry insights for Cox Automotive, an automotive services and technology provider. “This is a huge transition, and it’s so complex. It’s a change in lifestyle.” By 2030, she forecasts, EVs will account for close to half of new cars sold in the U.S.

Colorado’s mobile DMV rolls to the hard to reach

How do you live everyday life without an ID – apply for a job, get a bank account, or buy a house? It’s hard, as tens of millions of Americans can attest. But does it have to be that way? Colorado says no, and its roving DMV on wheels is helping residents reconnect with society.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Radio in hand, Steven Rustemeyer ushers the next person aboard the bus. “Head on up, buddy,” says the helper, stationed in a sunlit parking lot in Englewood, Colorado.

But this bus has no rows of seats, no driver or destination. This is a project of the Colorado Division of Motor Vehicles: a DMV on wheels. It sits parked with an office inside – complete with computer, printer, fingerprint reader, and vision test chart.

“It’s easier that way,” says Mr. Rustemeyer, who got a new ID from the mobile clinic earlier this year. Homeless for eight years since he aged out of foster care, he says he appreciates not having to pay bus fare to head to the brick-and-mortar office. The bus shows up once a month at a nonprofit whose job readiness program he attends – and where he’s helping out today.

As it issues IDs and licenses to hard-to-reach Coloradans, the DMV2GO program blunts bureaucracy by saving time and travel to traditional sites. Officially launched last year, the mobile program has issued around 11,000 documents as of September, stopping by incarceration sites, homeless shelters, universities, and rural community hubs.

Given how IDs are key to securing housing, work, and other basics, the goal is to ensure equitable access to identity services for all.

Colorado’s mobile DMV rolls to the hard to reach

Radio in hand, Steven Rustemeyer ushers the next person aboard the bus. “Head on up, buddy,” says the helper, stationed in a sunlit parking lot in Englewood, Colorado.

But this bus has no rows of seats, no driver or destination. This is a project of the Colorado Division of Motor Vehicles – a DMV on wheels. It sits parked with an office inside – complete with computer, printer, fingerprint reader, and vision test chart.

“It’s easier that way,” says Mr. Rustemeyer, who got a new ID from the mobile clinic earlier this year. Homeless for eight years since he aged out of foster care, he says he appreciates not having to pay bus fare to head to the brick-and-mortar office. The bus shows up once a month at a nonprofit whose job readiness program he attends – and where he’s helping out today. The stop is one of several across the state.

Next in line for a new license is Amber Taylor, with a purple ponytail. Also unhoused, she appreciates the convenience, too. Regular DMVs “give me panic attacks, because there’s so many people,” she says. So the smaller scale “is perfect.”

As it issues IDs and licenses to hard-to-reach Coloradans, the DMV2GO program blunts bureaucracy by saving time and travel to traditional sites. Officially launched last year, the mobile program has issued around 11,000 documents as of September, stopping by incarceration sites, homeless shelters, universities, and rural community hubs. Given how IDs are key to securing housing, work, and other basics, the goal is to ensure equitable access to identity services for all, says Desiree Trostel, the program manager.

It’s important to “meet people where they’re at,” Ms. Trostel says, “regardless of circumstance or location.”

Mobile staff members report more enjoyment on the job, too. Customers on the road are “a lot happier to come and see us,” says Liz Kuhlman, an upbeat licensing technician on the bus.

Help for older people

In mountainous Archuleta County, where there is no state DMV, Warren Brown says he and his wife saw the problem up close. At their former insurance business, part of the job meant helping older customers navigate license services online.

“In my mind, this just didn’t have to be that way,” says the county commissioner, who contacted the state for help. His constituents were first in line to benefit from the formal rollout of DMV2GO in 2022.

The clinics operate on a first-come, first-served basis, and residents can request visits to their community. Customers can apply for or renew driver’s licenses or ID cards, including out-of-state transfers. The clinic doesn’t offer knowledge tests or print the physical card on-site (those will arrive later by mail), but it does offer temporary ones.

The program, which was commended by a national DMV trade group this year, also drew inspiration from the Sunshine State.

The Florida Licensing on Wheels program, or FLOW, has operated since 1988, says David Brown, a FLOW program manager. Beyond making regular stops, it’s also grown to respond to manmade and natural disasters, including in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017. The mobile program served thousands of displaced Puerto Ricans at airports ahead of starting a new chapter in Florida, which no local DMV could have easily accommodated, says Mr. Brown.

“In order for you to start the process of rebuilding after a disaster, you need those solid credentials,” he says.

Next stop: The county jail

Rebuilding can also mean navigating society after incarceration. That’s why DMV2GO’s list of stops includes sites like the Jefferson County jail.

Small groups of men and women await their turn in a gray-walled room, at a table laid with capless pens. A state statute allows them to receive IDs for free at this jail just west of Denver.

Some people interviewed say they lost their former cards while experiencing homelessness. That includes Alex, a man in pretrial detention, who like others preferred not to publish his last name for privacy.

“I had it in my backpack, and then somebody stole my backpack,” Alex says of his ID. “You don’t realize how much you need it until you don’t have it.”

Another man, David, says he struggled with reentry when he last left prison after 26 years. Exiting with an ID this time will hopefully let him get “right into the workforce,” he says.

“This little, small step right here,” he says, is like a “blessing.”

Proper identification is considered an important – though understudied – factor in reentry, often necessary for securing jobs, housing, and health care, says Ryan Spohn, director of the Nebraska Center for Justice Research at the University of Nebraska Omaha.

Though the DMV2GO model sounds “fantastic,” says Dr. Spohn, and “something that other states might want to look at,” he notes that IDs alone aren’t sufficient for successful reentry.

Many inmates need help obtaining the right documents even to apply for an ID and have to deal with other logistical barriers such as transportation once they’re out. A driver’s license can help make critical appointments like parole and mandated counseling, for instance, but not everyone is eligible for one due to their criminal or driving record.

Convenience aside, mobile DMVs also aren’t without challenges. Spotty internet access in rural areas, for one, can complicate service. And in Colorado, demand is high for the program that currently involves four licensing technicians and three vehicles. The state says it’s gathering data on DMV2GO’s impact and hopes to expand.

That demand is clear at a recent stop at a public library in rural Westcliffe when a dozen people arrive ahead of the clinic’s opening at 10 a.m. Though a couple of locals note the wait, those in line still appreciate the service.

“This is awesome,” says John Van Doren, a retiree here for a license renewal. “Very convenient.”

Soon he’ll sit behind a small white screen and meet Bianca McCarl, the technician of the day. She readies a customer for the camera.

In a patient voice, she says, “You can smile your natural smile for the picture, OK?”

They can’t all be Scrooge: How holiday films shine

Twenty years ago, Hollywood got it right with two Christmas classics, “Elf” and “Love Actually.” But what is it that sets the best holiday films apart? Yes, redemption and innocence. But another ingredient you might not expect binds the two great eras of Christmas films.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Twenty years ago, a pair of Christmas movies made cash registers ring like jingle bells. In “Elf,” a human raised by elves searches for his father in New York City. “Love Actually” came out a week later. The British megahit features a patchwork of heartwarming, tragic, and raunchy storylines.

Those two films are credited with reinvigorating the Christmas movie genre. The recipe looks simple. Take one grumpy old soul crying out for redemption, possibly supernaturally aided. Sprinkle in holiday songs and sleigh bells. And budget for plenty of fake snow.

Yet for every occasional treat in the 21st century – including “The Holiday” and “Klaus” – many more turn out about as well as a homemade Christmas sweater. Too often, holiday movies forget the most important ingredients. Great Christmas stories tap into a longing for meaning in life – that love can actually transform us. That generosity matters. That sincerity might seem hokey in a cynical age, but that innocence has pride of place, especially at Christmas.

“Almost every Christmas movie has some character or characters transforming to better, higher versions of themselves,” says Jeremy Arnold, author of “Christmas in the Movies.” “That speaks to us because it’s the magic that we want Christmas to be.”

They can’t all be Scrooge: How holiday films shine

Twenty years ago, a pair of Christmas movies made cash registers ring like jingle bells. In “Elf,” a human raised by elves searches for his father in New York City. “Love Actually” came out a week later. The British megahit, nicknamed “Loathe Actually” by its detractors, features a patchwork of heartwarming, tragic, and raunchy Christmas storylines.

Those two films are credited with reinvigorating the Christmas movie genre. The recipe looks simple. Take one grumpy old soul crying out for redemption, possibly supernaturally aided. (If not ghosts, a dog will do.) Sprinkle in beloved holiday songs and sleigh bells. Add at least one embarrassing costume. Oh, and budget for plenty of fake snow.

Yet, for every occasional treat in the 21st century – including “The Holiday,” “Joyeux Noel,” and “Klaus” – many more turn out about as well as a homemade Christmas sweater. Too often, holiday movies forget the most important ingredients. Great Christmas stories tap into a longing for meaning in life – that love can actually transform us. That generosity matters. That sincerity might seem hokey in a cynical age, but that innocence has pride of place, especially at Christmas.

“Almost every Christmas movie has some character or characters transforming to better, higher versions of themselves,” says Jeremy Arnold, author of “Christmas in the Movies.” “That speaks to us because it’s the magic that we want Christmas to be.”

The “Christmas Carol” effect

The spirit of Ebenezer Scrooge looms over Christmas movies past, present, and yet to come. Charles Dickens pretty much invented the fictional genre with “A Christmas Carol,” and his protagonist has been embodied by dozens of actors – notably Alastair Sim, Patrick Stewart, George C. Scott, and Michael Caine – and a Disney cartoon duck. Some variations of the tale, such as the 1988 Bill Murray vehicle “Scrooged,” critique materialism.

“In a lot of our Christmas comedies, we see there is a built-in cynicism about our consumer culture and about how what was initially conceived of as a religious holiday has become a marketing bonanza and an occasion for getting stuff,” says film critic Ty Burr.

Countless other stories have modeled characters on Dickens’ iconic misanthrope, albeit without the Victorian sleeping cap. For instance, Alexander Payne’s new movie, “The Holdovers,” stars Paul Giamatti as a Scrooge-like boarding school teacher who is tasked with chaperoning a lonely student over the Christmas break. Dr. Seuss’ “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” (first adapted as an animated short and, later, a live-action film) features an avocado-shaped creature whose heart is two sizes too small. And in “One Magic Christmas” (1985), a rancorous suburban housewife (Mary Steenburgen) meets an unconventional angel (Harry Dean Stanton).

“He kills off her husband and children in a car crash and then brings them back [just] in time so that she can understand the true meaning of Christmas,” says Mr. Burr, author of “The Best Old Movies for Families.” “Believe it or not, the movie works. But boy, does it get dark. And it’s a Disney movie on top of everything else.”

The dark night of the soul is similarly bleak in Jimmy Stewart’s twin holiday classics, “It’s a Wonderful Life” and “The Shop Around the Corner.” Characters contemplate suicide, job loss, and financial ruin. In those films, human connection displaces the shadows.

The Cold War heightened that desire for security even more, says movie historian Vaughn Joy, who cites “White Christmas” and “It’s a Wonderful Life” as her two favorite holiday movies.

The 1950s were an era when home and the nuclear family were seen as sanctuaries. A number of postwar Christmas movies – including “Holiday Affair,” “Miracle on 34th Street,” and “The Bishop’s Wife” (a 1996 remake starred Whitney Houston) – depicted the family unit as the center of one’s financial and emotional security. “And [it] is made into the ultimate ideal of security and kindness and generosity that just kind of marries very well with Christmas,” Ms. Joy says.

Holiday fare as a way to heal

“It’s a Wonderful Life” director Frank Capra and Stewart both served in World War II and understood the importance of love and family during its aftermath. Indeed, the two greatest eras for Christmas movies came immediately after world-altering tragedies: World War II and 9/11, says Mr. Arnold.

“My argument is that since it takes a year or two to make a movie and get it into theaters, it really can be seen in part as a response to those national traumas,” he continues. “Audiences craved getting back together, being a community again, and sharing in a movie experience, laughing together and so on ... making them feel better and more secure at a time when they weren’t.”

In fact, “Elf” director Jon Favreau, a native New Yorker, saw the movie as an explicit attempt to reclaim New York after the terrorist attacks. He’s spoken about showing the city dressed in its holiday best and about the desire to give its children a reason to hope. (To the dismay of parents, young viewers may have tried to replicate Buddy the Elf’s favorite recipe: spaghetti covered in M&Ms, maple syrup, and chocolate sauce.)

“Love Actually” also was created in reaction to 9/11.

“It starts with that opening monologue by actor Hugh Grant, where he talks about when the messages people sent as the planes were going into the towers,” says Scott Meslow, author of “From Hollywood With Love.” “Even now for me, knowing that that’s coming, it’s still kind of a record scratch. ... We think of these movies in these kind of hazy, feel-good terms, and it’s like, no, it’s explicitly about the immediate post-9/11 political era.”

Director Richard Curtis shot clandestine footage of people reuniting at airports for his film, especially poignant in an era when people were afraid to fly. And his overlapping storylines crammed in as many different kinds of love as he could fit into 2 hours and 15 minutes.

The early 2020s, too, have been a time of bleakness, marred by pandemic and war. Somewhere, writers may be channeling their inner Charlie Browns, searching for the true meaning of the holiday.

In the words of the titular character of “Auntie Mame,” haul out the holly. Because we need a little Christmas now.

Looking for more festive flicks? Try one of these.

I’LL BE SEEING YOU (1944; not rated)

“It was an enormous hit at the time, and it’s just completely forgotten today. It’s rarely shown on TV. I don’t know why. In a way, it’s a typical star vehicle from 1944. It’s about two tortured souls, played by Ginger Rogers and Joseph Cotten. They’re each traumatized in some way, and the film is about them learning to trust each other and open up again. There’s a gentleness about it that seems to be fostered by the Christmas season. It’s a very sort of delicate kind of a film, but very touching.”

– Jeremy Arnold, author of “Christmas in the Movies: 35 Classics to Celebrate the Season”

REMEMBER THE NIGHT (1940; not rated)

“It’s a 1940 Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray romantic comedy about a district attorney who has to take the shoplifter – who he’s trying to put in jail – home for Christmas. It’s a lovely movie. There are scenes in it that are emotionally moving and touching genuinely in a way that you want from any romantic comedy. But also within the context of a holiday season feels heartfelt. What people want and so rarely get in a Christmas movie is the truth of the meaning. An honest, real, unforced, uncalculated feeling of emotional well-being toward other people.”

– Ty Burr, author of “Best Old Movies for Families: A Guide to Watching Together”

KLAUS (2019; rated PG for rude humor and mild action)

“It is a completely original story that Sergio Pablos wrote. There’s two families and they’re at war with each other, and the kids don’t know why they’re at war. The parents don’t even really know why. It’s centuries old. It forefronts children as the way of the future in a way that no Christmas film does. Pablos started a studio because he wanted to have complete control over this film. ... It is completely hand-drawn. You can just tell somebody put his entire heart into [drawing] every leaf in every frame.”

– Vaughn Joy, contributor to “Under the Mistletoe: Holiday Romance Films” (forthcoming, 2024)

HAPPIEST SEASON (2020; rated PG-13 for some language)

“That was a Hulu rom-com with Kristen Stewart. It’s dealing with ... somebody being afraid to come out to their family. There’s all these just unabashedly wacky scenes that are so divorced from any kind of ... reality. To me, that’s something you want from your Christmas romantic comedies.”

– Scott Meslow, author of “From Hollywood With Love: The Rise and Fall (and Rise Again) of the Romantic Comedy”

In Pictures

In Lebanon, the art of resistance endures

There are many forms of protest, and Lebanese citizens have tried them all. Their efforts to hold an entrenched and corrupt government to account have had soberingly little effect, yet the spirit still shines. Around Beirut, street art hits the eye like a spray-painted howl.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

In the years since Lebanon’s self-declared “October Revolution,” the country has been engulfed by a multitude of crises.

Three-quarters of the population has since been pushed below the poverty line, and shortages, power cuts, and surging prices have become facts of life.

Frustrated Lebanese citizens have even held up banks to withdraw their own money. As protests and the hope for change have dissipated, one constant has been vibrant, anti-government graffiti: spray-painted howls of anger and protest.

Expand this story to view the full photo essay.

In Lebanon, the art of resistance endures

Rarely have so many Lebanese turned out on the streets to demand wholesale political change as when they began their self-declared “October Revolution” of 2019. And rarely has there been so little positive result.

In recent years, Lebanon has been engulfed by a multitude of crises, starting with economic collapse in late 2019. The following year brought the COVID-19 pandemic. And in August 2020 came the second-largest nonnuclear explosion ever recorded, when illegally stored ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut exploded, taking more than 200 lives, forcing 300,000 from their homes, and leaving some $15 billion in damage.

Three-quarters of the population has since been pushed below the poverty line, and shortages, power cuts, and surging prices have become facts of life.

As protests and the hope for change have dissipated, and frustrated Lebanese citizens even held up banks to withdraw their own cash, one constant has been vibrant, anti-government graffiti: spray-painted howls of anger and protest.

Everywhere you look in the capital Beirut are reminders of people’s abiding distaste for their rulers, their banks, and a political elite that one analyst notes has chosen to “do nothing,” rather than “risk losing control over a system which has served them so well for so long.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Gaza truce as a marker for peace

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Long before the Hamas attack on Israel, the small nation of Qatar was busy overcoming big challenges. Like many other oil-rich Arab countries in the Persian Gulf, it was devising solutions to climate-driven water scarcity, a demographic “youth bulge,” and the prospect of declining oil revenues. Yet Qatar took the time in recent weeks to mediate a humanitarian truce in the Israel-Hamas war. That success, even if temporary, reflects a wider picture of a region trying to lay down markers for peace.

A small but good example was a decision this month by the six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – to offer a unified visa for easy travel between their countries. Such regional cooperation builds on last March’s deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia to normalize ties, as well as the 2020 accords that formalized relations between Israel and a number of Arab states.

The region’s most powerful leaders share “a view that their best interests lay in de-escalation and a focus on economic development,” writes John Raine, a senior adviser at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

Gaza truce as a marker for peace

Long before the Hamas attack on Israel in early October, the small nation of Qatar was busy overcoming big challenges. Like many other oil-rich Arab countries in the Persian Gulf, it was devising solutions to climate-driven water scarcity, a demographic “youth bulge,” and the prospect of declining oil revenues. Yet Qatar took the time in recent weeks to mediate a humanitarian truce in the Israel-Hamas war. That success, even if temporary, reflects a wider picture of a region trying to lay down markers for peace.

A small but good example was a decision this month by the six states of the Gulf Cooperation Council – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates – to offer a unified visa for easy travel between their countries. Such regional cooperation – similar to the European Union’s visa-free travel – builds on last March’s deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia to normalize ties, as well as the 2020 accords that formalized relations between Israel and a number of Arab states.

The region’s most powerful leaders share “a view that their best interests lay in de-escalation and a focus on economic development,” writes John Raine, a senior adviser at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “Retaining control of their and the region’s agenda is an unstated but implied objective.”

Another example was the Nov. 11-12 emergency summit of the Arab League and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation to discuss the conflict in Gaza. The most noteworthy result was the endorsement of the Palestine Liberation Organization as the legitimate representative of Palestinians – including those in Gaza. Other factions that recognize PLO leadership – meaning Hamas members that adopt peaceful means – could be included.

Gaza has seen multiple wars since 2007. Many in the Middle East now want to use this latest – and largest – war in Gaza to set a different direction for the region. Doing so requires building on triumphs of cooperation.

“If Israel and moderate Arab states can ultimately leverage this crisis for generational good, they could put their region on a more positive and sustainable glide path,” writes Frederick Kempe, president and CEO of the Atlantic Council.

Compared with the Middle East of past decades, today’s Middle East does not lack for bridge-builders, such as Qatar, Oman, Egypt, and Iraq. And wars like those in Gaza and Yemen are only one of the many issues. Leaders that are tackling those other issues – youth joblessness, for example – often end up as peacemakers. Shared interests can lead to shared values.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The rewards of giving

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Melanie Wahlberg

As God’s children, we always have it in us to help others – even if we’re feeling stuck ourselves.

The rewards of giving

Today we’re sharing an audio podcast that explores how a spiritual view of our capacity to give to others empowers us to help in a way that benefits all involved – including ourselves. In it, a woman shares how she experienced this firsthand in two challenging situations.

To listen, click the play button on the audio player above.

For an extended discussion on this topic, check out “The rewards of giving,” the Oct. 23, 2023, episode of the Sentinel Watch podcast.

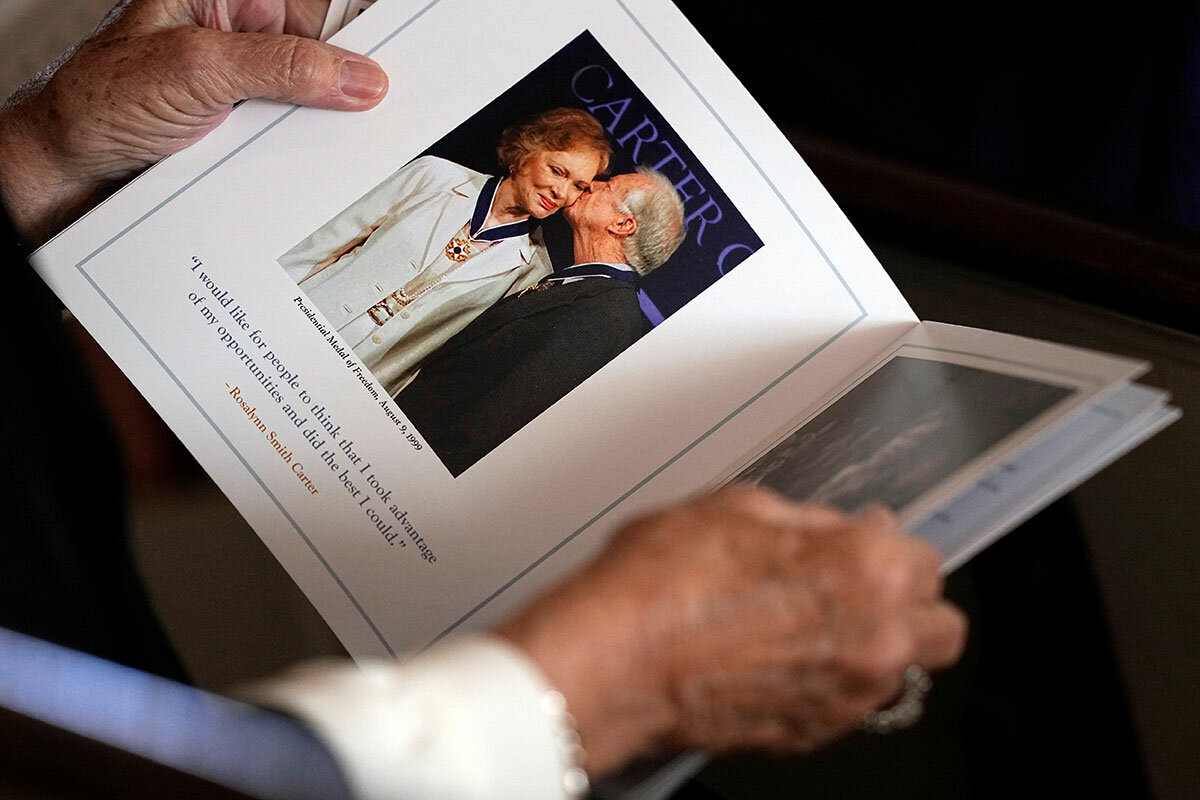

Viewfinder

The power of love

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Tomorrow we’ll take you to Maine, which is addressing child care needs with a Child Care Business Lab. The idea is to help aspiring child care providers navigate the business landscape and successfully launch their own centers. The result: child care in remote towns and immigrant communities.