- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What guides Monitor coverage of the Israel-Hamas war?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today’s Daily issue includes three stories on the Israel-Hamas war from different perspectives. It made me think: What is our approach to coverage of the war? So I asked our Middle East editor, Ken Kaplan. He had his answer ready, as though he was just waiting for me to ask.

“Our coverage has been distinctive because we focus on the humanity on both sides,” he told me. “We go places other people don’t – and resolutely.” He points to stories about Israeli civil society coming together, “and not in a warlike way, but to support each other – that’s so Monitor.” And he points to stories from on the ground in the Gaza Strip and West Bank – about mothers and Palestinians unable to get back to their families.

“It’s fundamental to what we do,” Ken says, “looking at the humanity in every story.”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

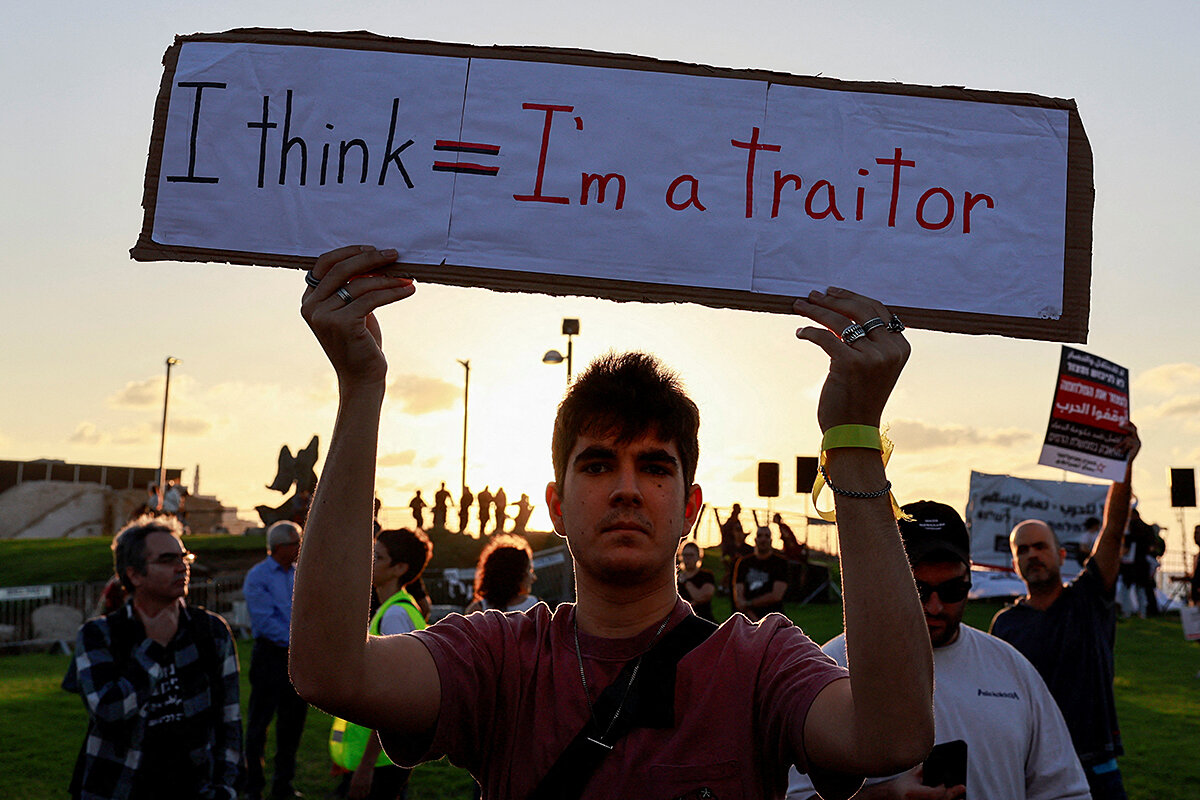

Israel curbs wartime freedom of expression. At what cost?

Israeli Arabs were seeing rising opportunities before the war. Now, some are being suspended from school or going to jail for social media posts. The crackdown risks unwinding decades of progress. Some Israeli business leaders, however, are pushing back.

Following the devastating attack of Oct. 7, Israel has pursued an extensive crackdown on freedom of expression that has led to jail time, lost jobs, and expulsions from universities for publicly expressing views deemed either treasonous or insufficiently supportive of Israel in its war with Hamas.

Experts warn that a kind of national loyalty campaign that focuses largely on Palestinians and Arab Israelis is almost certain to set back yearslong efforts to diversify the workforce and foster intercommunal peace through private sector initiatives.

“What we’re seeing is an unprecedented zero-tolerance policy for expressing any sympathy for the Palestinian people of Gaza,” says Ari Remez, communications coordinator for Adalah, a legal defense organization promoting Arab Israelis’ rights. “The government is trying to send a message that the citizenship of Palestinians of Israel is conditioned on adhering to the Israeli perspective on the war.”

The war is already having a chilling effect on Arab Israelis’ educational and employment aspirations, says Maisam Jaljuli, CEO of Tsofen, an organization that works to expand professional opportunities for Arab Israelis. “We realize we’re going to have to make a big effort after this war just to hold onto the successes we’ve had,” she says.

Israel curbs wartime freedom of expression. At what cost?

On a Sunday in early October, Bayan Khateeb, a Palestinian living near Nazareth, Israel, was preparing a shakshuka – soft-boiled eggs in a spicy tomato sauce – for a group of friends.

Known to be a deplorable cook, the fourth-year engineering student triumphantly posted a photo of the simmering dish on Instagram with the caption “We will soon be eating the victory shakshuka” and a Palestinian flag emoji.

The problem for Ms. Khateeb is that she posted what she says was a kind of “Yes, I can!” to her friends on Oct. 8 – a day after the devastating Hamas attack in southern Israel, which was met with spontaneous celebrations in Gaza and the West Bank.

What followed would illustrate an extensive crackdown across Israel on freedom of expression in the wake of the Oct. 7 attacks and indeed punishment – jail time, lost jobs, expulsions from universities – for publicly expressed views deemed either treasonous or insufficiently supportive of Israel in its war with Hamas.

Moreover, some experts warn, a kind of national loyalty campaign that focuses largely on Palestinians and Arab Israelis is almost certain to set back yearslong efforts to diversify the workforce in key economic sectors and foster intercommunal peace through private sector initiatives.

“We are very concerned about the future of shared workplaces in Israel,” says Maisam Jaljuli, CEO of Tsofen, an organization that works to expand professional opportunities for Arab Israelis.

The war is already having a chilling effect on Arab Israelis’ educational and employment aspirations, Ms. Jaljuli says. She adds, “We realize we’re going to have to make a big effort after this war just to hold onto the successes we’ve had.”

Denounced by fellow students

In the days following Ms. Khateeb’s social media post, a group of Jewish students at Ms. Khateeb’s school, the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa – denounced her to the administration for her shakshuka post, which it considered to be pro-Hamas incitement. Ms. Khateeb was arrested and held overnight.

Later she offered Technion administrators and a court her shakshuka story and averred that she is not political, but focused on her studies and on building a career in tech. Nevertheless, she was ordered to serve five days of house arrest in her town of Kafr Kanna and was prohibited from using social media. She was suspended by the Technion and currently awaits the university’s final decision on her enrollment.

Alarmed civil rights defenders say cases like Ms. Khateeb’s have exploded since Oct. 7.

“What we have been able to document is a growing crackdown on the freedom of speech and expression of Palestinian citizens of Israel since the war began,” says Ari Remez, communications coordinator for Adalah, a legal defense organization promoting Arab Israelis’ rights.

“What we’re seeing is an unprecedented zero-tolerance policy for expressing any sympathy for the Palestinian people of Gaza,” he adds. “The government is trying to send a message that the citizenship of Palestinians of Israel is conditioned on adhering to the Israeli perspective on the war.”

Israel is not alone in this battle over the speech and fundamental rights repercussions of the Israel-Hamas war. The confrontation has renewed the world’s long-dormant attention to the Palestinian cause and stoked heated emotional debates and global spikes in antisemitism and Islamophobia.

And it’s not just in Israel that expressions of opinion normally considered protected speech have led to firings and student suspensions. In one case in the United States, the doctor who directed New York University’s Langone Health’s cancer center, Benjamin Neel, was fired for reposting on social media anti-Hamas cartoons that in some cases included offensive caricatures of Arabs.

Dr. Neel also questioned the death toll in Gaza from Israel’s bombing campaign – a skepticism expressed last month by President Joe Biden, for which he has subsequently apologized.

Quantifying the crackdown

Yet in part because Israel has long been hailed as the Middle East’s sole democracy, with all the rights democratic rule is supposed to guarantee, infringement on those rights is garnering special attention.

In a tally of arrests, interrogations, and detainments of Palestinian citizens of Israel from Oct. 7 to Nov. 7, Adalah recorded 214 cases related to alleged speech offenses or political activity related to the war.

Of those cases, almost half involved social media posts – often brought to authorities’ attention by fellow students of the post’s author.

Adalah also found that through Nov. 11, 52 students enrolled at 32 different institutions of higher education were suspended without a hearing, while eight were expelled before a hearing. Complaints were canceled or the accused people were exonerated in 11 cases.

“What’s really unprecedented is the number of cases where students have been suspended and even expelled over social media posts,” Mr. Remez says.

At Tsofen, where expanding Arab Israeli employment and diversifying workplaces are the focus, Ms. Jaljuli says growing public attention to cases of Arab Israelis losing jobs over posts and other means of speech is causing a sense of foreboding among job seekers focused on the tech industry.

“There’s a real fear even among job candidates who don’t post on social media that the cases of people being fired for expressing any view related to the war will affect their chances,” she says. “They are afraid that when the companies see their name they will throw out their CVs.”

Some economic analysts have speculated that the war could actually benefit Arab Israeli job seekers in Israel’s dynamic tech sector. With so many Jewish Israeli reservists mobilized to fight the war, qualified non-Jews could become more attractive, they say.

Ms. Jaljuli has her doubts. Arab Israelis make up only 3% of the tech industry workforce, and even that meager number is concentrated in international tech companies in Israel, she says, not in Israeli companies.

Backers of diversity

The long-term employment impact of the war and the related cases of discrimination against Arab Israelis won’t be known for months or even years, Ms. Jaljuli says. But she adds that Tsofen is already planning for the postwar period. It is envisioning seminars for employment seekers on the do’s and don’ts of social media posting and a public service campaign with slogans like “We need to work together – especially now” and “Working together – this is the answer.”

And some big names in Israeli investment and job creation are touting the role that diversity in workplaces can play in healing Israeli society’s wounds and promoting intercommunal peace.

Many Israelis were surprised when Eyal Waldman – founder of the computer chip-maker Mellanox Technologies who is known for opening offices in the West Bank and employing dozens of Palestinians – expressed continuing support last month for peace through economic development, even after his daughter and her boyfriend were killed by Hamas at the Nova music festival Oct. 7.

Similar thinking has come from Jonathan Medved, founder and CEO of OurCrowd, an equity crowdfunding platform, who is widely known as Israel’s “startup guru.”

At a recent Zoom briefing on the war’s impact on the Israeli economy, Mr. Medved was upbeat on prospects for building Israeli-Palestinian peace through sharing in the prosperity of a dynamic economy.

The way to make the next war less likely, he said, “is by investing in joint projects and making sure we create economic horizons for our neighbors as well as for Palestinians here.”

Neither side in the long conflict is “going anywhere; we have to live together,” he said, adding that a peaceful coexistence will require participation by every segment of society to “build economic ties and ... create better lives for everybody.”

In Gaza’s shadow, a climate summit on war and peace

The Israel-Hamas war has reached even into the COP28 summit, which is supposed to be about climate change. Maybe that’s appropriate, some say. Worldwide, climate disruption is already intertwined with stability. Addressing it can create conditions for peace.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

From protests to pilot projects, the issue of war and peace has arrived at the United Nations’ climate summit in Dubai. The Israel-Hamas conflict is very much in thought, and participants here say conflict and climate can no longer be treated as separate issues in a fragile world reeling from both.

Gaza, for example, faces not just war but also rising water scarcity and saltwater intrusion into groundwater due to rising sea levels.

Already one major outcome of the summit this week is the COP28 Declaration on Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace. Governments are pledging to fund climate resilience in war-torn or fragile nations and communities.

Governments and U.N. organizations also said they’ll develop pilot projects on resilience in the Horn of Africa – a region hit by drought and floods, and home to three ongoing conflicts and 3 million refugees.

The next step, many COP28 participants say, is to ensure pledges are translated into action.

“People on the front lines are experts in the field. They have their own solutions but lack the resources to act,” says James Thuch Madhier, a participant at COP28 from South Sudan. With resources, “not only will they provide their own solutions to adapt to climate change, but this can even lead to solutions to conflict.”

In Gaza’s shadow, a climate summit on war and peace

Protest chants at this week’s global climate summit have been dominated by calls for a cease-fire as well as for cutting carbon. People are focused not just on 1.5 – the threshold degrees, in Celsius, of warming set by the Paris Agreement that the world is at risk of overshooting – but also on 14,000, the number of Palestinians reported killed in Gaza.

Activists from as far away as Colombia and the Marshall Islands are setting their eyes on militaries and war along with big oil as major spoilers to climate progress.

In more ways than one, the issue of war and peace has arrived at the United Nations’ annual Conference of Parties (COP) on climate here in Dubai. Simply put, policymakers and activists say conflict and climate can no longer be treated as separate issues in a fragile world reeling from both.

To a degree not seen in the prior 27 COP meetings, participants are highlighting the need to collaborate proactively to prevent climate and conflict from feeding on each other, both now and in the hotter future that scientists predict for the planet. For leaders here, this means, for one thing, looking to boost climate adaptation and resilience for at-risk communities and to address climate stressors before they exacerbate or reignite conflict.

The next step, many COP28 participants say, is to ensure pledges are translated into change on the ground.

“The focus placed this year on fragile and conflict affected countries is very welcomed as it means the most vulnerable communities, which are the front lines of climate change, are explicitly included in the climate action,” Nimo Hassan, COP delegate and director of the Somalia NGO Consortium, representing Somali nongovernmental organizations, told the Monitor on Tuesday. “But how will success be measured? By the number of policies adapted, pledges to commit funds, or by the impact on affected communities’ lives and livelihood?”

Summit eyes “blind spot” – conflict

One example of how questions of peace and conflict are taking center stage: This past Sunday saw the first-ever day focused on themes of relief, recovery, and peace at a COP summit, addressing what host nation the United Arab Emirates described as a “blind spot” in climate discussions.

Panels focused on ways to fund and fast-track projects for communities in drought-struck, flood-hit, and war-ravaged regions where governments are barely functioning and basic security is lacking. Several speakers cited World Bank figures indicating 15 out of the 25 most climate-vulnerable countries in the world are in conflict or at risk.

Already one major outcome of talks this week was the COP28 Declaration on Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace, signed by governments including the United States. The document pledges to increase funds for climate resilience in war-torn or fragile nations and communities, with an eye toward both sustainable development and “conflict prevention and inclusive peace building.”

Some parts of the world are already hot spots of both climate and conflict.

Exhibit A is the Horn of Africa – a region hit by drought and floods, and home to three ongoing conflicts and 3 million refugees. U.N. organizations and governments declared their intent to develop pilot projects there, starting with a regional climate security coordination group to preempt disasters.

The efforts here go broader, too. Humanitarian groups are brainstorming ways to work with banks, development organizations, and others to preemptively assist front-line communities to avert disasters like the flooding and dam failure in Derna, Libya, that killed about 20,000 people in September.

“The climate emergency is punishing displaced people three times; it tears them from their homes, it compounds their crisis in exile, and destroys their homeland, preventing them from returning,” Filippo Grandi, U.N. high commissioner for refugees, cautioned here on Sunday. “The climate emergency exacerbates displacement and human suffering.”

Gaza ever-present

Even as policymakers explore new pathways for peace and progress, the shadow of Gaza looms over COP28.

The end of an Israel-Hamas cease-fire overshadowed the first full day of the conference on Thursday. Mentions of Gaza are ubiquitous in COP28 speeches and side events this week. The Iranian delegation walked out of the talks in protest over Israel’s ongoing participation in the summit.

A World Bank report released here revealed that Gaza is facing increased water scarcity and saltwater intrusion into groundwater due to rising sea levels – increasing poverty levels in the most climate-hit communities prior to the war – a trend that will impact both Palestinian and Israeli lives.

Two hundred justice activists protested in solidarity with Gaza on Sunday, a rare demonstration in tightly controlled UAE that marked the first pro-Palestine protest on Emirati soil in more than a decade.

Wearing white-and-black Palestinian kaffiyehs and carrying banners reading “ceasefire now,” climate activists from Africa, Latin America, Pacific Islands, and Asia chanted, “There is no climate justice without human rights!” Some wept as they read out the names of Palestinian children killed by Israeli bombs in Gaza.

The gathering attracted a large crowd among participants and country delegates, some of whom hugged the activists. Others painted murals of Palestinian women at the conference’s women’s pavilion.

Climate activists say ongoing protests and signs of support aim to send the message that global climate progress is inseparable from addressing conflict.

“We are all connected; this is a global village. Just as we want climate justice for our communities in Bangladesh, there must be justice for Palestinians in Gaza,” says Raoman Smita, a Bangladeshi climate justice advocate for the Dhaka-based Global Law Thinkers.

“How can we move forward on climate when there is war? Even on an environmental front, look at all the damage the war in Gaza is doing to the coastline, the water, the pollution from phosphorous bombs,” she said. “Wars don’t just delay climate progress; they make climate disasters worse.”

A coalition of feminist and Indigenous groups protested on Sunday, demanding, “No wars, no warming.” The groups urged governments to “address the elephant in the room” – militaries’ carbon footprint and what the groups claim as diversion of resources to militaries rather than to climate action.

Story of hope from South Sudan

People hailing from conflict-hit nations have also taken center stage here alongside government officials, carrying a simple message: Climate action in war-ravaged states is not only possible, but also a matter of life and death.

James Thuch Madhier, from South Sudan, who spoke on a panel featuring U.N. and government ministers, said resilience and adaptation are the only ways forward for war-hit communities that are often displaced multiple times by war, drought and floods. His story is proof.

After being driven from South Sudan by conflict as a teenager, he returned to his homeland in 2017 and developed a solar-powered pump, well, and micro-drip irrigation systems that are now helping farmers to collect water year-round amid weather extremes.

Mr. Madhier says that while the slow inclusion of conflict-hit communities in the U.N. process is a “good first step,” in the end “we need less talk, more action.”

“People on the front lines are experts in the field. They have their own solutions but lack the resources to act,” says Mr. Madhier on the conference sidelines. With resources, “not only will they provide their own solutions to adapt to climate change, but this can even lead to solutions to conflict.”

‘The elephant in the room’: How US schools are talking about the Mideast

Walkouts. Threats to Jewish and Islamic students. Inflammatory columns in school newspapers. Schools are struggling with how to address the Middle East war. Finding a way forward includes helping students feel physically safe. But it also means supporting their curiosity and thoughtfulness.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

How do you create “compassionate global citizens”? That’s the question facing U.S. schools in the throes of the Israel-Hamas war.

At the Kawananakoa Middle School in Honolulu, teachers are raising the situation in the Mideast, but are not telling students what or how to think about it, says Vice Principal Bebi Davis. Instead, they are nurturing intellectually curious students.

“You don’t want to keep them so sheltered that when they’re faced with a challenge, they don’t know how to balance their thoughts and emotions,” Dr. Davis says.

The school’s approach offers a window into how K-12 educators are grappling with teaching amid a divisive global conflict. High schoolers are staging walkouts, student journalists are writing editorials using the term genocide, and in at least one case, students have threatened a teacher. School responses to spikes in antisemitism and Islamophobia in the United States have ranged from beefing up security to leaning into affinity groups to help foster understanding.

The emotionally charged moment makes schools even more important, says Joey Hailpern, a school board member in Evanston/Skokie School District 65 in Illinois.

“That’s the obligation that we have – to develop better citizens and a stronger community,” says the former teacher and principal.

‘The elephant in the room’: How US schools are talking about the Mideast

How do you create “compassionate global citizens”? That’s the question facing U.S. schools in the throes of the Israel-Hamas war.

What that looks like at the Kawananakoa Middle School in Honolulu is students comparing and contrasting a natural disaster – the deadly Maui wildfire in August – with the human-created conflict in the Middle East. It also includes a teacher and student teacher pairing up to offer a lesson on recent history in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Teachers are not telling students what or how to think about the complex situation in Israel and Gaza, says Vice Principal Bebi Davis. Instead, they are nurturing intellectually curious students.

“You don’t want to keep them so sheltered that when they’re faced with a challenge, they don’t know how to balance their thoughts and emotions,” Dr. Davis says.

The approach offers a window into how K-12 educators are grappling with teaching amid a divisive global conflict. High schoolers are staging walkouts, student journalists are writing editorials using the term genocide, and in at least one case, students have threatened a teacher. School responses to spikes in antisemitism and Islamophobia in the United States have ranged from beefed-up security and intentional lessons – like those at Kawananakoa Middle School – to leaning into affinity groups to help foster understanding.

The emotionally charged moment makes schools even more important, says Joey Hailpern, a member of the Evanston/Skokie School District 65 Board of Education in Illinois.

“That’s the obligation that we have – to develop better citizens and a stronger community and to model what it’s like to do the work of bringing people together, so that they can leave our education spaces into the world together,” says Mr. Hailpern, a former teacher and principal.

“A turning point”

Since October, the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights has opened more than a dozen investigations at K-12 and higher education institutions after alleged discrimination based on shared ancestry or ethnic characteristics. Several of the nation’s largest K-12 school systems – in New York, Las Vegas, and Tampa, Florida – are among those under investigation.

Rania Mustafa, executive director of the Palestinian American Community Center in Clifton, New Jersey, says some private Islamic schools have canceled outdoor recess and altered pickup procedures in a bid to bolster student safety.

Zainab Chaudry, director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations office in Maryland, says the group has received reports of female Muslim students wearing hooded sweatshirts in place of their traditional hijabs, while others are shying away from revealing their Palestinian American identity to classmates.

When Ms. Mustafa’s sixth grade nephew wore his keffiyeh, a traditional Palestinian garment, to school, another student called him a terrorist, she says.

“This has been a turning point in our communities, where now we are beginning to realize the importance of speaking up,” Ms. Mustafa says. In the case of her nephew, he told a guidance counselor.

Jewish schools, too, have increased security amid threats. And Jewish students have been subject to bullying and harassment, especially as their peers are “blurring the lines” between antisemitic rhetoric and criticism of Israel, says Aaron Bregman, director of high school affairs for the American Jewish Committee.

“Just because they’re Jewish, students are being essentially connected to the Israeli government,” he says. “It gets them scared. It gets them intimidated.”

“Dialogue is the only way”

Apart from hardening physical infrastructure, schools are sorting out how to start and continue conversations.

Some schools or districts have remained silent, forgoing any public statements or sidestepping discussion with students. In New Jersey, the Palestinian American Community Center questioned one district seemingly taking that approach, and after an inquiry, administrators changed course, says Ms. Mustafa.

At the very least, she says, schools should be providing mental health support to students affected by the conflict. But she also sees schools as a “controlled environment” where children can discuss and learn about these challenging topics – as long as they’re not politicized in favor of one side.

“At the end of the day, dialogue is the only way that anyone can move forward as a society and as a community,” Ms. Mustafa says. “Ignoring the elephant in the room is never the solution.”

The American Jewish Committee recently issued guidance for how public and private schools could confront antisemitism. The recommendations include, among others, training staff on how to discuss the conflict, supporting affinity groups, and hosting interfaith panels.

In an age of polarization, Mr. Bregman, of the American Jewish Committee, says it’s especially important to introduce students to the nuance underpinning global events.

“There’s not just one solution and ... there’s just not one answer,” he says. “And the more that kids have that discourse to talk this out, the more that we’re going to be in a better place moving forward and that nothing like this ever happens again.”

“Hate has no home here”

In Evanston, Illinois, two board members took it upon themselves to set the example. Mr. Hailpern, who is Jewish, co-wrote a letter with fellow board member Omar Salem, who is Palestinian. The letter acknowledges the pain caused by the conflict while also affirming the district’s schools as a safe space for students. “While processing and healing as a community, hate has no home here,” it states.

Mr. Salem says he thinks the letter, sent to district staff and families, offered a slice of hope and kept the focus on the children. “We can’t change what governments are going to do. But we can focus on Evanston Skokie District 65 and our kids and our community members,” he says.

In other places, cultural appreciation initiatives that took root before the Israel-Hamas war are proving helpful.

Two years ago, Beachwood City Schools – located in a diverse suburb outside Cleveland – launched family-led affinity groups after a parent brought concerns regarding language barriers to the administration, says Kevin T. Houchins Sr., the district’s director of equity and community engagement.

The groups serve as a place where parents can connect, support, and encourage each other while also improving cultural understanding in a district where 42% of students are white, 25% are African American, 21% are Asian, 8% are multiracial, and 4% are Latino. Beachwood is also known for having a large Jewish population.

Affinity groups exist for families of African American, Chinese, Hispanic and Latino, Indian American, Muslim, and neurodiverse students. Israeli families plan to start one as well, Mr. Houchins says.

The district community is “taking the time to actually listen and absorb and immerse ourselves into different cultures,” he says. “It has been really exciting.”

The groups hold their own meetings but also participate in quarterly “seat at the table” get-togethers, where district leaders listen to concerns and suggestions, Mr. Houchins says. From that feedback, Beachwood City Schools updated its academic calendar, closing schools on the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Fitr; for Diwali, the Indian festival of lights; and for Lunar New Year in Chinese culture.

The groups have been organizing cultural events, too, drawing families that previously had not participated in many school-based activities, says Mr. Houchins. He saw evidence of the growing cross-cultural bonds when affinity groups reached out to the district after the Oct. 7 attack on Israeli citizens that launched the war and asked how they could help.

“As they begin to learn more about each other, it helps us in times of crisis,” he says.

In Honolulu, it was a newsletter to families that explained the “global citizens” idea and detailed how educators are addressing the Israel-Hamas war.

Absent discourse and learning at school, Dr. Davis, the vice principal, worries students will resort to their phones for a less reliable source: social media. And she never wants to stifle curious minds.

“Kids want to talk about everything,” she says.

Even the difficult stuff.

Why Pakistan struggles to stop honor killings

Pakistani police have arrested several men for the alleged honor killing of a teenage girl. A photo of her with a man not from her family circulated on social media. Experts say such killings are a growing problem in Pakistan. They describe a difficult – but not impossible – path forward.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Police have arrested four men for the alleged honor killing of an 18-year-old girl in the north Pakistan district of Kohistan last week, including the victim’s father. Authorities say the teenager was shot by her family on the instructions of a village council, or jirga, after appearing in a photo with a man.

Hundreds of Pakistani women are murdered every year in so-called honor killings. Few perpetrators are ever convicted.

The Kohistan incident has sparked outrage across the country and reignited a conversation about Pakistan’s failure to protect women. Given the need to patch legal loopholes, address deeply rooted cultures of misogyny, and strengthen support systems for women, advocates say curbing honor killings will require all hands on deck – and enthusiastic backing from the state.

“In this area, there is an extremely strict control over women’s bodies and sexuality, and these things are monitored very closely,” says feminist scholar Farzana Bari. “The state hasn’t invested anything in people’s education, nor does it have much control, so the area is governed by local tribal elders and because their thinking is so patriarchal, they often make these sorts of decisions.”

She wants Pakistan to declare a national emergency, and push to eradicate gender-based violence.

“It isn’t rocket science,” she says.

Why Pakistan struggles to stop honor killings

Police have arrested four men for the alleged killing of an 18-year-old girl in the north Pakistan district of Kohistan last week, including the victim’s father, in a case that has sparked outrage across the country and reignited a conversation about Pakistan’s failure to protect women.

Authorities say the teenager was shot by her family on the instructions of a village council, or jirga, as a way to restore her family’s honor. Her alleged infraction? Posing in a photo with a man.

Hundreds of Pakistani women are murdered every year in so-called honor killings – homicides committed because the women in question are judged to have transgressed social mores through indecent behavior, thus bringing shame on their families. In many instances, honor killings are triggered by rumor or doctored evidence, and few perpetrators are ever convicted.

The Kohistan incident has underscored all that is needed to curb honor killings, from patching legal loopholes to addressing deeply rooted cultures of misogyny to strengthening support systems for women. Advocates say cultural and legal efforts to protect women will require all hands on deck – and enthusiastic backing from the state.

“Honor killing in Pakistan is an abhorrent ... practice that has no place in our modern society,” says Malaika Raza, the general secretary of the human rights wing of the Pakistan People’s Party. “We must unite as a collective force against this grave violation of human dignity.”

Patriarchal anxieties

In this remote and deeply conservative district, several women have been killed in the name of honor in recent years.

This incident echoes a similar case in May 2012, when a video surfaced of a group of girls singing in the presence of men from a different tribe. It resulted in the convention of a similar jirga. Then, as now, tribal elders handed down a death sentence to those visible in the footage, leading to the deaths of at least eight people.

“In this area, there is an extremely strict control over women’s bodies and sexuality, and these things are monitored very closely,” says feminist scholar Farzana Bari. “The state hasn’t invested anything in people’s education, nor does it have much control, so the area is governed by local tribal elders and because their thinking is so patriarchal, they often make these sorts of decisions.”

Khawar Mumtaz, who served as the chairperson of the National Commission on the Status of Women and has been a women’s rights activist for more than four decades, believes the practice is spreading.

“When we started looking at honor killings, it used to be in small pockets of certain areas,” she says. “But over the years, what has happened with migration is that it has spread all over the place.”

Experts note that recent examples reveal an increasing level of patriarchal anxiety surrounding social media, and the opportunities and visibility it provides women.

“In some parts of the country, the mere presence of a woman in public is considered obscene,” says human rights campaigner Usama Khilji. “What social media has done is given women the freedom to express themselves, to enjoy themselves, to sing and to dance – so of course the old guard of the patriarchy has been quite upset by that.”

If patriarchal anxieties are the fuel of the crisis, Pakistan’s parallel legal systems are the vehicle. Mr. Khilji opines that the inefficiency and corruption of Pakistan’s criminal justice system leads some parts of the country to put their faith in the judgments of tribal elders.

“The biggest criticism of the jirga system has been the way it is quite anti-woman and quite misogynistic,” he says. “It’s pretty much elderly men that have status, privilege, and prestige in society-making decisions.”

Legal impunity

But even the mainstream legal system in Pakistan has been criticized for allowing perpetrators of honor killings to evade punishment. Under the Pakistan Penal Code, the murderer may have his sentence commuted if they are pardoned by or come to a financial arrangement with the victim’s family. Since honor killings are almost always carried out by close relatives, such pardons are common.

Human rights defender Tahira Abdullah believes it is too easy for killers to “circumvent the law through forgiveness and compromise settlements.”

“The only way Pakistani women can escape dishonor killings is for the state to become the complainant in court cases filed on behalf of the victims,” she says.

In 2016, after social media influencer Qandeel Baloch was killed by her brother for allegedly defaming the honor of her family, Pakistan’s Parliament attempted to close this loophole by requiring that courts sentence anyone convicted of an honor killing to a minimum of life imprisonment.

However, critics say the amendment places the burden of proving motive squarely on the prosecution. Those accused may evade the life sentence by claiming they killed the victim for reasons other than honor.

“It all comes back to this sense that women are the property of the family ... and they’re also disposable,” says Ms. Mumtaz. “The state’s failure is not providing justice and not providing safe places for victims to hide themselves.”

Seeking safety

Part of the solution, according to police officer Amna Baig, is for victims to engage law enforcement at the first sign of trouble.

“I have dealt with hundreds of cases of femicide and most of them have been honor killings,” she says. “Trust me, a victim usually knows that this is coming. She knows what’s happening around her and she understands the level of threat – but what she doesn’t often know is how to access the police and how to seek that help.”

In order to ensure speedy access to justice, Ms. Baig helped create the Gender Protection Unit of the Islamabad Police, a department staffed almost entirely with female officers who act as the first port of call for women being abused or facing threats of violence.

“If there is an early intervention ... the chances of this escalating into an honor killing go down,” she says.

For Dr. Bari, the academic, the problem can only be eradicated with a concerted campaign that focuses as much on education as on access to justice.

“In the long term, if you want to attack the root causes of this issue, you will have to change the patriarchal mindset that views the woman as the property of the man,” she says. “We need to declare a national emergency and launch a nationwide campaign to create awareness around gender-based violence. It isn’t rocket science, but who is going to do it? It’s clear that it isn’t a priority for the state.”

Ice cream nation: Does Ecuador take the cherry?

In our final story, we consider the rather shocking assertion that Ecuador loves ice cream more than any other nation on the planet. We invite you to not be offended and to judge for yourself. But consider: Does your country have ice-cream monuments and art exhibits?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

A celebration in Ecuador isn’t a celebration unless ice cream is involved. That’s Angél Lozado’s viewpoint.

That’s not surprising. His great-great-great-great grandmother, Rosalia Suárez, is believed to have “invented” a wildly popular style of ice cream, helado de paila, made in a copper pot with ice. Living in the north-central city of Ibarra at the foot of the formerly snow-covered Imbabura volcano, she is said to have used ice from the surrounding mountains to create her fruity desserts. Today, most of the glaciers are long gone, but Mr. Lozado carries on the tradition by running Helados de Paila Fifth Generation Rosalia Suárez.

But this pride is not just marketing. From statues to art exhibits dedicated to ice cream – and the fact that it’s simply ubiquitous at any hour of any day of the week – the frozen treat has a special place in this Andean nation. “I eat ice cream every single day,” says Javier Lasluisa, a chef and professor of culinary arts at the Universidad de Las Américas in Quito. “It’s an off day if I don’t at least taste it.”

Ice cream nation: Does Ecuador take the cherry?

Everyone loves ice cream. But Ecuadorians, particularly in Andean cities, are convinced they love it more than anywhere else. There are art exhibits made about it, a monument dedicated to it, no celebration is considered complete without it, and it’s everywhere – even early on a weekday morning.

From colorfully layered creamsicles sold informally out of travel coolers to perfectly swirled soft-serve to the traditional sorbet-like helado de paila, the capital’s historic center is a bastion of cool, creamy treats.

“I eat ice cream every single day,” says Javier Lasluisa, a chef and professor of culinary arts at the Universidad de Las Amricas in Quito. “It’s an off day if I don’t at least taste it.” His father and grandfather were both “ice cream men,” he says, making and selling the treat. And he and his wife recently started developing recipes for their own ice cream brand. He acknowledges it may not be daily fare for all Ecuadorians, but it’s a pillar at any special event or festival in the Andean zone of the nation.

“We are a country that values our traditions, and ice cream is a part of that,” he says.

Down a steep slope from the historic center’s Independence Square is a creamy-yellow building that for the past 165 years has housed the San Agustín ice cream parlor. In a back room, up narrow stone steps, Joel Basurto stirs fresh coconut pulp and milk in a copper dish set atop a rough pile of ice and rock-salt, which are inside yet another copper container. After about 15 minutes of mixing round and round by hand, it slowly starts to solidify into the local treat, helado de paila. Small pieces of fresh coconut punctuate the thick, chilled dessert.

“Young or old, rain or shine, day or night, for Quiteños it’s always a good time for ice cream,” says manager Javier Muñiz. The cashier, dressed up in purple monk’s robes, says he sells scores of cones a day – not counting dine-in customers. Aside from the form in which the ice cream is made, part of what makes it so special are fresh local fruits like the taxo, also known as a banana passion fruit, or cherimoya, a custard apple.

No celebration without ice cream

Local legend has it that Angél Lozado’s great-great-great-great grandmother Rosalia Suárez “invented” this style of ice cream in Ecuador. Living in the north-central city of Ibarra at the foot of the formerly snow-covered Imbabura volcano, she is said to have used ice from the surrounding mountains to create her fruity concoctions.

Today, most of the glaciers are long gone, but Mr. Lozado carries on the tradition by running Helados de Paila Fifth Generation Rosalia Suárez. Five generations later, he acknowledges that he has a lot of extended family running their own ice cream operations, big and small. And although he has moved toward a more industrialized approach to ice cream production, he says he still rents his services making the copper-pot traditional version for weddings and parties.

“One can function without ice cream, but a celebration doesn’t feel complete without it,” Mr. Lozado says. “The tradition of eating ice cream is in many ways kept alive by making it the old-fashioned way,” he says.

There is a permanent monument portraying a layered ice cream at the entrance to the town of Salcedo, about two hours south of Quito, and temporary art exhibits pay homage to the goody here as well.

Martina Miño Pérez, an Ecuadorian visual artist and cook, has organized several interactive art projects that revolve around ice cream, taste, and memory. The idea was sparked, in part, by memories of a childhood birthday party and how she can feel transported back to that moment and her mother’s homemade ice cream when eating lemon-flavored sweets.

One of her works, exhibited at Quito’s contemporary art museum in 2020, consisted of six ice cream flavors that were meant to reflect different shared experiences in the museum’s neighborhood of San Juan. There was the bittersweet flavor of one ice cream meant to encapsulate the feelings of being a woman social organizer; another had an acidic base with some subtle heat, meant to represent the work of trying to make ends meet during the pandemic. The exhibit built bridges between the community and the museum by sending an ice cream cart out into the streets with these edible works of art.

“Ice cream is a good way to symbolize memory,” she says. “Memory is never fully intact, it’s always incomplete. Frozen in time until it melts away.”

Back in the historic center, Jean, who arrived here from the Democratic Republic of Congo two years ago, crosses the street on crutches – with an ice cream cone held perilously in one already-full hand.

He says he rarely ate it back home. But since arriving in Quito? “It’s everywhere you look,” he says. “Some days, you just need a little treat.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Chile’s patient shaping of a constitution

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For the second time in just over a year, Chileans are poised to vote on a new draft constitution this month. From a strictly legal sense, the exercise hardly seems necessary. The current constitution has been amended more than 60 times since its adoption in 1980. Its problem isn’t rigidity.

“The big difference,” Sergio Toro, a political scientist at the Universidad Mayor de Santiago, told Le Monde, “is that [the new draft] was written in a democracy.”

In a country noted for economic stability, minimal corruption, and the rule of law, that observation captures what makes Chile’s pursuit of legal reform unique in a region where constitutions – as one Chilean study put it – are “disposable.” A long and traumatic military dictatorship that ended in 1990 left Chile as one of the world’s most distrustful and unequal societies. Now, its citizens are seeking new currencies of social and political faith through justice and equality.

Chile’s patient shaping of a constitution

For the second time in just over a year, Chileans are poised to vote on a new draft constitution this month. From a strictly legal sense, the exercise hardly seems necessary. The current constitution has been amended more than 60 times since its adoption in 1980. Its problem isn’t rigidity.

“The big difference,” Sergio Toro, a political scientist at the Universidad Mayor de Santiago, told Le Monde, “is that [the new draft] was written in a democracy.”

In a country noted for economic stability, minimal corruption, and the rule of law, that observation captures what makes Chile’s pursuit of legal reform unique in a region where constitutions – as one Chilean study put it – are “disposable.” A long and traumatic military dictatorship that ended in 1990 left Chile as one of the world’s most distrustful and unequal societies. Now, its citizens are seeking new currencies of social and political faith through justice and equality.

“For progress to be made ... we need to re-engage citizens,” former President Michelle Bachelet told the Brussels-based journal International Politics and Society last week. “When people are just treading water ... they need to have hope that they will be treated with the respect and dignity they deserve.”

The constitutional reform process mirrors the way Chileans build trust through patience. In 2019, a tiny increase in subway fares sparked mass protests in Santiago, the capital, in a society long frustrated by social and economic inequalities. That marked the first zig. A referendum on drafting a new constitution won nearly 80% approval and the election of the country’s most left-leaning government since before the 1973 coup.

Then came the first zag. A constitutional assembly dominated by leftist groups produced an unwieldy draft with 355 articles. When it was put to a vote in September 2022, 60% of Chileans rejected it. A second zig followed. The government set in place a tiered, more disciplined process involving a council of experts and two review panels. This time, voters gave conservatives control of the drafting process.

Yet another zag may be coming. Polls show that voters appear ready to reject the new draft, a more modest set of reforms that hews closer to the current constitution, on Dec. 17. The first draft was too liberal; the second may prove too conservative.

Where some observers see risk to the country’s reputation for stability and economic credibility, others see political maturity. Voter participation is mandatory. In the run-up to the referendum, the government has set up distribution points across the country to hand out free copies of the new draft.

“The constitutional process is a space conducive to trust and hope and to establish the foundations that can sustain a more equal and fair country,” observed Jan Jarab, the United Nations human rights regional representative.

Latin America has seen nearly 200 constitutions, an average of more than 10 per country, reflecting a long cadence of revolutions, dictatorships, and economic crises. Chileans are interrupting that trend, seeking a new code of governing norms and rights based on inclusive principles rather than on politics.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

See God’s universe

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

-

By Elizabeth Mata

Considering things from God’s perspective brings out harmony, joy, and grace, as this poem conveys.

See God’s universe

Sometimes there appears before us a

thing so breathtakingly beautiful that it

reframes the moment outside time. For

me, it’s a full moon-lit night of treetops

as fine openwork across a silver-tinged

expanse, or the flawless artistry of a

cat’s markings. You must have yours.

Right then, when so awed, we can look

farther and deeper, however unimaginable

it seems; we can see it as a promise

of the present truth it hints at: a higher,

indissoluble stunning – the pure spiritual

goodness that is ever present, tangible,

no matter the human circumstance.

This wondrous good is God’s universe here,

now; the truth of God, Spirit, our divine

Parent and us, His children, embraced as

one offspring in wholeness; each of us

individually reflecting Spirit’s harmony,

order, purity – our spiritual nature – all

moving together without collision; no

division in this one true reality.

Hearts open, we pray to God to show us

His universe; to feel its spiritual power

and unity undergirding all acts of justice,

of generosity, and scattering the murk of

hostility that would hide all that is good;

then, with Spirit-sprung, wide-eyed joy

that drinks in a fresh view, we catch our

lives blessed in grace like never before.

Viewfinder

Ash and shadow

A look ahead

Thank you for spending time with us today. We’re working on a host of stories that might interest you, from Scott Peterson’s visit to Israeli communities along the war’s front line to an attempt by a United States university to teach a “viewpoint-neutral history of the Middle East.” Is that even possible?

We’ll also look at community college students who are transferring to the Ivy League. It’s a huge gulf to leap. We talk with the people helping them.