- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Does ‘neutral’ Middle East history exist? California is trying to find out.

- Kevin McCarthy is leaving Congress. He’s not alone.

- In Israeli border town, rockets a reminder Hamas is unbeaten

- From community college to MIT? Students find a new path to a degree.

- Can US prisons take a page from Norway? Five questions.

- How an ‘Ambulance for Monuments’ is preserving Romanian culture

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Is the era of the amateur student-athlete ending?

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

That rumble you hear is the world of college sports being shaken to its core. For 117 years, the National Collegiate Athletic Association has been built on the tenet of amateurism. On Tuesday, the president of the NCAA proposed changing that. Schools with top programs could pay student-athletes endorsement deals, and even establish trusts for them.

The proposal is just a proposal. But the Olympics have already learned this lesson. Amateurism is a privilege. Only people with a decent amount of wealth can afford to be amateurs. Of course, young American athletes with pro dreams usually had nowhere else to go but to the NCAA. But there’s an honesty to universities’ acknowledging their essential role in the professional sports ecosystem – and considering how to share the staggering profits they make from that arrangement.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Does ‘neutral’ Middle East history exist? California is trying to find out.

The University of California vowed to develop programs with a “viewpoint-neutral history of the Middle East.” Some professors see it as a first step toward thought police. Who decides what’s neutral? To foster greater understanding, more viewpoints are needed, not fewer, they say.

American colleges and universities are grappling with how to address wildly varying viewpoints of the Israel-Hamas war, amid mounting tensions and incidents of violence in educational communities.

As part of a slate of initiatives, one major university system said it will develop programming with a “viewpoint-neutral history of the Middle East.” But the recent move by the University of California stirred more controversy than it relieved – with strong pushback from professors concerned about sacrificing academic freedom.

More than 150 UC professors signed a letter to the UC president taking issue with the idea of viewpoint-neutral programs as a way to combat antisemitism and Islamophobia. The president’s office clarified the program would be voluntary and extracurricular. But the question of neutrality lingers, especially among experts who point out that academic exploration leads to the formation of a viewpoint.

The controversy comes at a moment of scrutiny for university leaders. On Tuesday, the presidents of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Pennsylvania testified before a congressional committee about antisemitism on their campuses.

The university’s job isn’t to neutralize viewpoints, but to foster discussion, debate, and disagreement to bridge different viewpoints, says Sherene Seikaly, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at UC Santa Barbara.

Does ‘neutral’ Middle East history exist? California is trying to find out.

American colleges and universities are grappling with how to address wildly varying viewpoints of the Israel-Hamas war, amid mounting tensions and incidents of violence in educational communities.

As part of a slate of initiatives, one major university system said it will develop programming with a “viewpoint-neutral history of the Middle East.” But the recent move by the University of California stirred more controversy than it relieved – with strong pushback from professors concerned about sacrificing academic freedom.

More than 150 UC professors signed a letter to the UC president taking issue with the idea of viewpoint-neutral programs as a way to combat antisemitism and Islamophobia. The president’s office responded by clarifying the program would be voluntary and extracurricular. But the question of neutrality lingers, especially among experts who point out that the very act of academic exploration leads to the inevitable formation of a viewpoint.

The attempt at ensuring safe and equitable policies for expression on college campuses and the swift response from professors underscore the tricky nature of balancing intellectual exploration with pressure on school administrators to answer for extreme views expressed on campus. Also at play is the role of universities in fostering dialogue and understanding during moments of crisis.

The controversy comes at a moment of scrutiny for many university leaders. On Tuesday, the presidents of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Pennsylvania faced sharp questions from Republican lawmakers as they testified before a congressional committee about antisemitism on their campuses. The U.S. Department of Education has launched investigations into allegations of antisemitism or Islamophobia at 13 colleges and universities since Nov. 16.

The UC initiative and subsequent concerns present a “disconnect between our aspirations for a place where everyone can be equally welcome, which is the kind of thing administrations think about, and the applicability of the term ‘viewpoint neutrality’ to the endeavors of teaching,” says Lara Schwartz, director of the Project on Civic Discourse at American University.

Viewpoint neutrality, as a legal term, means that university policies cannot vary according to viewpoint, says Professor Schwartz, who is also a constitutional law expert. The Supreme Court has ruled that student fees at public universities, for example, cannot be withheld from campus organizations based on a group’s beliefs.

But academic content requires a wide range of viewpoints, argue professors from history, humanities, and social sciences departments across UC campuses. “There is a clear, structural difference between government agencies avoiding the endorsement of a particular political position and university-based professionals presenting conflicting viewpoints as a normal part of our curriculum,” the professors wrote in their letter to the president. The signers represent a small but vocal portion of the 25,000 professors in the system.

Who decides what is neutral?

The University of California – a 10-campus public school system serving nearly 300,000 students – announced the $7 million plan on Nov. 15. Initiatives include:

- $3 million for emergency mental health resources for students, faculty, and staff.

- $2 million for leadership training for educators, focused on freedom of expression; academic freedom; and diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging.

- $2 million for the development of educational programs “focused on better understanding anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, how to recognize and combat extremism, and a viewpoint-neutral history of the Middle East.”

The announcement rang alarm bells for some faculty who saw it as a first step toward curbing what content they could teach in their classes.

There is no contradiction between having a viewpoint and producing history with integrity, says Jennifer Derr, founding director of the Center for Middle East and North Africa at UC Santa Cruz, who signed the letter. When students come to her class thinking of history as a collection of objective names and dates, she says, part of her role is to show all the decisions that go into presenting a narrative.

“That is never a neutral act,” she adds. “It’s based on an assessment of what is historically significant, what we have evidence for, what plays into the larger notions of a just society that we are oftentimes wrestling with.”

Addressing professors’ concerns, UC President Michael Drake’s office wrote, “The University of California remains deeply committed to shared governance and the academic freedom of our faculty. The president’s remarks were referencing voluntary educational programming on our campuses, not classroom content or curriculum.”

Who decides what’s neutral? asks Sherene Seikaly, director of the Center for Middle East Studies at UC Santa Barbara and one of the professors who signed the letter. The university’s job, she says, isn’t to neutralize viewpoints – it’s to foster discussion, debate, and disagreement to bridge different viewpoints.

“You don’t resolve tensions by parroting only one side of the tension and not engaging the other side. ... So how do you resolve conflict? You talk to people. You talk to your scholars; you talk to your students. And that is actually, on my campus, precisely what is happening. We’re talking to each other,” she says.

Professors at campuses around the United States are bringing together faculty experts – who often have different ideological viewpoints on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – to lead campus discussions about the conflict. For example, at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, Centre College in Kentucky, and Elon University in North Carolina, faculty are reportedly guiding students through earnest, respectful conversations about the war in Gaza and the region’s history. That is what universities do best, says Professor Schwartz: research, learning, teaching, and dialogue.

Differing applications

In their letter to President Drake, professors wrote that his use of the term “viewpoint-neutral” calls into question their academic integrity and is “an unneeded rebuke of the rigorous work done by our colleagues who spend significant time developing and delivering world-class curriculum and pedagogy.”

Viewpoint neutrality in university regulations is essential, especially for public schools, points out Professor Schwartz. “This idea that you would have to be viewpoint neutral in your regulations, in the way you treat different people and different actions and different expressions and scholarship, that’s not just important because you’re a university. That’s required because you’re the government; it’s the First Amendment,” she explains.

Schools that violate this neutrality can lose their federal funding.

But applied to curricula, viewpoint neutrality undermines what’s powerful about the practice of history in a democratic society, says Dr. Derr at UC Santa Cruz.

“This idea of presenting conflicting ideas in the classroom and thinking about those conflicting ideas through historical evidence critically, this to me is the work of [historians],” she says. “And I think it’s the kind of work that should be celebrated in moments of political difficulty.”

Kevin McCarthy is leaving Congress. He’s not alone.

Former U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy announced today that he is resigning. An unusual number of members of Congress are leaving – even those in high-ranking positions. It speaks to the changing political environment.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

The “young gun” from California who rose rapidly through Republican ranks and eventually became speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives announced Wednesday that he would resign later this month.

Rep. Kevin McCarthy, whose nine-month speakership ended with his ouster in October, announced his departure in a Wall Street Journal op-ed. He touted the American dream, with a nod to his journey as a firefighter’s son who became a golden boy of GOP politics.

While he didn’t mention the rancor that surrounded his toppling this fall, it’s no secret that the political environment in Congress had become intolerable. And not just for Mr. McCarthy.

In November alone, 13 senators and members of the House announced they were leaving, the highest number in more than a decade. Among those leaving are committee chairs, and members who disproportionately care about making a difference in legislation, says GOP pollster Whit Ayres.

The wave of retirements has been interpreted by many as further evidence of dysfunction in Congress – though some stepping down are running for higher office or have cited health issues.

“It probably reflects the level of duress that members have been experiencing,” says Kevin Kosar of the American Enterprise Institute in Washington. “The level of partisan rancor just keeps ratcheting up.”

Kevin McCarthy is leaving Congress. He’s not alone.

The “young gun” from California who rose rapidly through Republican ranks and eventually became speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives announced Wednesday that he would resign later this month.

Rep. Kevin McCarthy, whose turbulent nine-month speakership ended with his abrupt ouster in October, announced his departure with a characteristically upbeat op-ed in The Wall Street Journal. He touted the American dream, with a nod to his own journey as the son of a firefighter who became a golden boy of GOP politics, first in California’s state Legislature and then in Congress.

But while there was no mention of the personal and political rancor that surrounded his toppling this fall, it is no secret that the political environment in Congress had become intolerable for Mr. McCarthy 16 years after he took office.

“His ouster from the speakership and his decision to retire from the House are the product of a Congress in which polarization has become the norm and trust the exception,” said veteran Democratic Rep. Steny Hoyer in a statement, noting that despite opposing policy views the two became friends over their years.

Mr. McCarthy’s departure comes on the heels of an unusually high number of lawmakers announcing that they are stepping down or will not seek reelection. In November alone, 13 senators and members of the House announced they were leaving – the highest number in more than a decade. The wave of retirements has been interpreted by many as further evidence of dysfunction in Congress, with more members concluding the personal sacrifices are no longer worth it – though those stepping down have given a range of reasons for their decision, including running for higher office.

“It probably reflects the level of duress that members have been experiencing,” says Kevin Kosar, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, noting that House members spent an unusual 10 straight weeks in session this fall, dealing with two narrowly averted government shutdowns and the speakership saga. “The level of partisan rancor just keeps ratcheting up and makes it a truly stressful, unpleasant environment to work in.”

Mr. McCarthy’s departure leaves Republicans with an even slimmer House majority. With the recent expulsion of Rep. George Santos last week, the GOP ranks fell to 221 members – just three above the 218 majority needed to pass legislation.

A special election to replace Mr. Santos is expected in February, in a district that’s considered a toss-up. GOP Rep. Bill Johnson of Ohio announced last month that he would step down by March to lead Youngstown State University.

Of the roughly three dozen members of the House who will not be seeking reelection in 2024, two-thirds are Democrats. Some are leaving to run for higher offices, including state attorney general, governor, and senator. Others have just had it.

“When we’re doing work that is satisfying, like we did in the last Congress, it’s a lot easier ... for my family to say, ‘Yeah, this is important and meaningful work,’” Democratic Rep. Dan Kildee of Michigan said on MSNBC recently, explaining his decision to step down after a health scare earlier this year.

“For me, the personal decision really is the larger part of this,” he added. “But it’s hard to erase the fact that the Congress that I’ve seen in the last few years is not even close to what I saw when I was elected in 2012.”

It’s not uncommon for the minority party or the party that expects to be in the minority after the next election to see departures. But this early, it’s still unclear which party is likely to hold control after the 2024 elections. In addition to 21 Democrats, more than a dozen Republicans, including some who are leading committees and subcommittees, are stepping down.

“The GOP in the House has had so much bad media [attention] on them because of all these scandals and the fights and the struggle to be able to govern and the very limited productivity,” says Dr. Kosar. “It’s not wrong for GOP representatives to be saying, ‘You know, maybe we’re going to get wiped out next autumn and lose our majority, in which case I’ll get out.’”

Rep. Patrick McHenry of North Carolina, a McCarthy ally who chairs the House Financial Services Committee and served as speaker pro tem during the chaotic three-week effort this fall to elect a new speaker, announced yesterday that he would not seek reelection. Rep. Kay Granger of Texas, chair of the House Appropriations Committee, is also retiring. And Rep. Brad Wenstrup of Ohio, who chairs a select subcommittee on the pandemic that has investigated key GOP concerns, including alleged government obfuscation about COVID-19 origins, is also among those leaving. All three are Republicans.

Republican pollster Whit Ayres says that while there’s always turnover in the House, it’s highly unusual to have so many people leave early – particularly leaders of the party.

“It speaks to the incredibly toxic atmosphere in the House,” he says. The members leaving “are disproportionately the kinds of people who really want to make a difference in legislation, and really care about the reputation of the House.”

In Israeli border town, rockets a reminder Hamas is unbeaten

How close is Israel to reestablishing a sense of safety? The Israeli border town of Sderot is an interesting case study. It has been the target of Hamas rockets for years. Now, the town is largely empty, and rockets are still flying despite Israel’s massive offensive.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Located barely half a mile from the Gaza Strip, the Israeli town of Sderot has long been in Hamas’ crosshairs. A display case in the municipal offices includes remnants of several Hamas rockets fired over the years.

But despite more than eight weeks of heavy Israeli bombardment of Hamas targets in Gaza, and an intensifying ground incursion, Hamas is proving it can still launch hundreds of rockets into Israel. Regularly, debris rains down on Sderot after missiles of Israel’s Iron Dome air defense system intercept the rockets overhead.

Today just an estimated 5,000 residents remain out of a prewar population of 36,000.

“They are traumatized. ... They want security,” says Yaron Sasson, the spokesperson for Sderot. “They want to know there is no chance of a single rocket from Gaza.”

A woman who gave the name Diana, who was visiting briefly to care for her cats, says 20 years living in Sderot has meant learning to “live with bombs.” Her home is near a synagogue that was struck by a rocket Sunday.

“We have to be patient,” she says. “This is our home, and we have to fight for it. We [Jews] got this country because we need it, not because we want to push Palestinians out.”

In Israeli border town, rockets a reminder Hamas is unbeaten

The relentless fire of Israeli artillery provides the noisy soundtrack in this largely emptied front-line Israeli town, its scenes of grassy suburbia located barely a half-mile – as the rocket flies – from the northeast corner of the Gaza Strip.

But despite more than eight weeks of intense Israeli bombardment of Hamas targets in Gaza, and a ground incursion that has left most of the now-decimated northern strip under Israeli control, there is another, parallel soundtrack over Sderot that surprises many here.

Every day Hamas, the Islamist militant group that rules Gaza, proves it can still launch rockets into Israel, with several hundred fired so far since the collapse of a weeklong cease-fire last Friday. And every day, missiles of Israel’s Iron Dome short-range air defense system fly into the air to knock the rockets out with a burst and puff of smoke that rains debris down on Sderot and other Israeli towns.

“We thought when the IDF [Israel Defense Forces] go to Gaza, and go inside and destroyed terrorists, there is no rockets,” says Yaron Sasson, the spokesperson for Sderot who wears a pistol tucked into his belt. “But they still shoot rockets at Sderot, at Tel Aviv, Ramat Gan, Be’er Sheva, all the area.”

Israel has vowed to “destroy” Hamas after it mounted an attack Oct. 7 that overran more than 20 Israeli communities, leaving 1,200 people dead and 240 taken hostage, Israel says. In Sderot alone, rampaging Hamas fighters killed 50 people that day.

With Israel still reeling from its most traumatic losses since the Jewish state’s founding 75 years ago, politicians and the IDF alike are vowing to permanently remove Hamas as a threat. But continued rocket fire, two months into the war, underscores the challenge of finding and eliminating a potent and carefully hidden arsenal.

“I think we know that we are at the middle of the beginning, and I think we know it’s going to take a long while,” says an IDF reservist major in Sderot, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the press. Ultimately, he adds, “a lot is going to depend on the relationship between us and the Palestinians – it’s never going to be the same.”

Indeed, even by the violent high bar set by previous Israel-Hamas flare-ups, the level of destruction in the current conflict is staggering. Israel says it struck more than 14,000 targets in the first month of war alone, and has destroyed 500 of the 800 underground tunnel shafts it has so far discovered.

The result has been the pulverization of swaths of northern Gaza, and the deaths of some 15,900 Palestinians – the majority of them women and children – according to officials of the Hamas-run health ministry. The United Nations and relief agencies warn of a deepening catastrophe for 2.2 million Gaza residents, most now squeezed into the south of the narrow coastal strip.

“Still hundreds” of rockets

But even as Israel now wages what it calls “aggressive” ground operations against the southern city of Khan Yunis, which the IDF says includes some of the fiercest close-quarter combat of the war, Hamas has continued to target Israel with rockets.

“They’re still firing hundreds [of rockets] toward Israel, all over,” an IDF spokesperson, Lt. Col. Richard Hecht, told journalists Tuesday, when asked by the Monitor about post-cease-fire Hamas rocket launches.

“So it’s still hundreds; they still hold that capability. And we are still hunting down that capability,” he said.

Israel is finding “unprecedented” Hamas fortifications embedded in civilian areas, Lieutenant Colonel Hecht said, including schools used for shooting positions against advancing IDF troops. Israeli officials estimate that 5,000 Hamas fighters have been killed out of a prewar force of 30,000, in addition to 1,000 killed in Israel Oct. 7.

But on the eve of the cease-fire, which began Nov. 24, Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian of Iran said Hamas leaders assured him that the Palestinian fighters still had 90% of their “capabilities, forces, and weapons.” Iran has bankrolled Hamas as part of its anti-Israel and anti-Western “Axis of Resistance,” and been instrumental in improving its war readiness.

Some of Hamas’ arsenal has been expended in Sderot, which has been targeted by 400 Hamas rockets since Oct. 7, with 250 of those slipping through Iron Dome defenses, says Mr. Sasson, the town spokesperson. The tempo has decreased, with a handful of rockets each day, but on Sunday a rocket tore through the roof of an empty synagogue.

To “live with bombs”

Located so closely to the border with Gaza, Sderot has long been in Hamas’ crosshairs. A display case in the municipal offices includes remnants of several Hamas rockets fired over the years.

Today Sderot remains largely a ghost town, with estimates of just 5,000 residents remaining out of a prewar population of 36,000. Those who have left – more than 30,000 people – are now spread across the entire country and living in 110 separate hotels.

“They are traumatized. ... They want and they hope that soon they can come back to their homes in Sderot, but they want security,” says Mr. Sasson, speaking as a drone buzzes overhead and Israeli artillery fire disturbs the birds. “They want to know there is no chance of a single rocket from Gaza. They want to know if their child goes to the swimming pool or onto the street, that they will not be injured or killed.”

That standard is far from being met for a woman who gave the name Diana, who says 20 years living in Sderot has meant learning to “live with bombs.” Her low-slung family house is near the synagogue struck Sunday, across a street now strewn with broken glass and red roof tiles. She visited briefly Monday, to care for her cats.

“We have to be patient,” she says. “This is our home, and we have to fight for it. We [Jews] got this country because we need it, not because we want to push Palestinians out.”

But Diana says she is a “realist” and believes coexistence is unlikely with Hamas. “They say, ‘There will come a time when Jews will not be here,’” she says.

Ensuring that that does not happen is the aim of the reservist major, who says the purpose of Israel’s offensive is to allow people to return home, “not to hold people in hotels for the next six months.”

“People who live here don’t want to see a museum of destroyed houses; they want to see life,” says the major. Continued Hamas rocket fire is “exactly why there is no other choice” than a ground offensive.

Ashkelon’s “war routine”

Vying for the title of the most rocketed city in Israel is Ashkelon, just a few miles north of Sderot on the Mediterranean coast. Since Oct. 7, some 1,300 Hamas rockets have been fired at Ashkelon, with 200 of them falling in the city area.

Residents have learned to live with a new “war routine,” says municipal spokesperson Dana Grinblat, adding that it has been an “absolute miracle” that only two people died under rocket fire, considering that 25,000 of its 158,000 residents have no access to bomb shelters.

Ashkelon was targeted by 296 Hamas rockets Oct. 7, with 48 of them landing.

Sirens sounded again Tuesday morning, as a rocket landed on a residential building, wounding two people. It was one of more than 25 Hamas rockets to target Ashkelon since the cease-fire collapsed, nearly all destroyed by Iron Dome.

“It’s a little bit confusing,” says Ms. Grinblat, about how Hamas continues to fire rockets, after so many weeks of Israeli bombardment. But she adds, “It’s nothing like in the first weeks.

“We really hope that, after the war, we won’t need the shelters,” she says. “But I think that may be too optimistic.”

From community college to MIT? Students find a new path to a degree.

To help more people obtain a four-year degree, one initiative started with a simple idea: What if you make it easier for top community college students to connect with selective schools?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Chase Kuhleman is a senior at Cornell University in New York majoring in applied economics and management. He plans to apply to Cornell’s law school next year.

His post-high school education started online at Delaware County Community College, just outside of Philadelphia. He got a 4.0 GPA after his first semester and was recruited to join the Transfer Scholars Network, a program that helps students get into top-tier schools. Since the program’s debut in 2021, 32 students have been accepted by 16 partner schools, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, and Princeton. Some 600 students have been accepted and mentored by the network.

The partner institutions often have more resources to help support students complete a four-year degree – something fewer than 20% of community college transfers achieve within six years, according to new federal data.

At times Mr. Kuhleman felt imposter syndrome at the Ivy League school, but he doesn’t like to dwell on the past. “I can definitely say sometimes I used to think, you know, do I really belong here?” he says. “But I also sit and think, I’m just glad to be here. I’m very fortunate to have found my way to Cornell.”

From community college to MIT? Students find a new path to a degree.

Subin Kim was headed to college at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona straight out of high school – until the United States Army came calling.

As a soldier, he did a tour in his native country of South Korea and back in the U.S. at Fort Drum in New York. After the Army, he settled in Virginia, where his wife is from, and enrolled in Northern Virginia Community College.

He always planned to pursue a college education, but he says what happened next was not what he expected: He ended up at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Mr. Kim is one of 32 community college students who have successfully transferred to some of the most selective U.S. colleges and universities through the Transfer Scholars Network. Launched in 2021, the TSN offers a path to top-tier schools such as MIT, Yale, and Princeton. These colleges and universities often have more resources to help support students complete a four-year degree – something fewer than 20% of community college transfers achieve within 6 years, according to new federal data.

“We did research back in 2018 that showed there were 50,000 community college students with at least a 3.5 GPA that would be competitive for admission at [selective] schools ... but were not going, were not considering, or applying to these schools,” says Adam Rabinowitz, a spokesperson for the Aspen Institute’s College Excellence Program, which helped create the network.

The idea was to bring those students – some 15,000 of which were at the top of their classes – to the attention of top-tier schools, he says, adding, “What can we do to create a network where they actually connect with community colleges?”

Close to 80% of community college students receiving federal financial aid plan to transfer to a four-year college and earn a bachelor’s degree, but only about 16% end up graduating within six years, according to new research released by the U.S. Department of Education in November. The rates for students from low-income families and students of color are even lower.

To make higher ed outcomes more equitable, “we need leaders to dramatically level up their support for transfer students,” said U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona in a press statement.

Overcoming doubts

Currently, 16 four-year colleges and universities, including Brown, Wellesley, Rice, and MIT, are a part of the Transfer Scholars Network. Many highly competitive schools have single-digit acceptance rates, with some hovering around 5%. MIT, for example, accepts only 4.8% of applicants. Community college advisers at participating schools look for first-year high-performing students, and invite them to apply to the Transfer Scholars Network. They consider students holistically – if they are veterans, parents, or first-generation college students. Students also must earn less than $100,000 annually.

Once they are accepted to one of the 16 partner schools, they receive financial aid packages that fill 100% of their need via grants, scholarships, and minimal loans. If students don’t get into one of those schools, they can still stay in the TSN and get mentoring help applying to other colleges and universities. Six hundred students overall have participated in the program, including 250 current students.

“One of the big challenges that we have ... is that a lot of times students just automatically assume that certain institutions, especially private institutions, are going to be too expensive,” says Jennifer Nelson, coordinator of university transfer and initiatives at Northern Virginia Community College, which, as a TSN partner, regularly sends students to elite schools. “Especially the institutions that are part of the TSN, they’ve made a commitment to making these educational experiences affordable for transfer students.”

Chase Kuhleman is a TSN participant and a senior at Cornell University majoring in applied economics and management. Classically trained as a pianist, he left high school in Pittsburgh wanting to major in music. While he applied to a few four-year colleges, the pandemic made getting access to studios a problem: He couldn’t send schools recordings of his playing. “I had to withdraw and consider a different route,” he says.

That route was online at Delaware County Community College, just outside Philadelphia. He got a 4.0 after his first semester and was recruited to join the TSN. The money tripped him up: He was raised by a single parent who makes just enough for him not to qualify for a Pell Grant.

“To be honest, I wasn’t really certain [about applying], because I know when you reach for really highly selective schools, they often come with a hefty price tag,” Mr. Kuhleman reflects. “So I thought it would be a really great thing, but also a pipe dream.”

He was accepted at Cornell, received a financial aid package, and was left with a bill that his single mom could afford to pay over his remaining two years.

The school paired him with other transfer students to help him acclimate to campus. He now has a GPA of 3.65 and plans to apply to Cornell’s law school next year.

At times he felt imposter syndrome at the Ivy League school, but he doesn’t like to dwell on the past. “I can definitely say sometimes I used to think, you know, do I really belong here?” he says. “But I also sit and think, I’m just glad to be here. I’m very fortunate to have found my way to Cornell.”

A small dent

Graduating with a four-year degree is often difficult for community college students.

“If there’s a higher percentage of students from disadvantaged groups in the community colleges, and you do something that’s just for the community colleges, you will be more likely to help students from those groups,” says Alexandra Logue, a scholar who wrote about the problems with transferring credits in her book “Pathways to Reform: Credits and Conflict at the City University of New York.”

Many community college students drop out after the first year, Dr. Logue says. They also can have trouble transferring credits to four-year schools, get discouraged because of the need to take remedial courses in math, miss registration deadlines, or simply never show up after admittance, she says.

Specialized programs, such as the Transfer Scholars Network, while helpful, she says, only make a small dent in the number of students who need help making the transition to a four-year school. At City University of New York, for example, there are about 10,000 students a year who transfer in, switching from an associate degree to a bachelor’s degree.

She also wishes bigger universities and highly selective institutions, beyond just committing to meeting financial aid needs, paid more attention to integrating new students into a campus community – like pairing them with other transfers and having support groups.

Transitioning was tough for Mr. Kim. Now a junior in his second year at MIT, he is 30 years old, but most other transfers who came in with him were 20 or 21. His wife stayed in Virginia to work.

His first year, he took courses like physics and Calculus 3 that required problem sets weekly after a series of lectures. Learning from other students made him sharper.

Having bright students learn from each other is by design, says Stuart Schmill, dean of admissions at MIT. “Every student that we admit, we’re looking for academic excellence and personal excellence,” Mr. Schmill says. “And the students that we’ve brought in from the Transfer Scholar Network and in general from community colleges are remarkable individuals.”

Many transfer students are humble, he adds, “but make no mistake, these are really outstanding young people.”

School is still not easy for Mr. Kim, but he has made friends as co-president of the Transfer Student Association and is working with the Student Veterans Association. His life philosophy has guided him from the start.

“What I experienced in the military helped me understand that if I want to get something,” he says, “I have to go out of my way to try, even if I fail.”

The Explainer

Can US prisons take a page from Norway? Five questions.

Prisons in the United States do comparatively little to prepare incarcerated populations for their release. Norway is on the opposite end of the spectrum, even letting some incarcerated people cook their own meals. Several U.S. prisons are taking notice.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

About 2 out of 3 Americans released from jails and prisons per year are arrested again, and 50% are re-incarcerated. In Norway, that rate is as low as 20%.

As more U.S. states seek to improve their correctional systems, the Norwegian model could prove key. It aims to create a less hostile environment, both for people serving time and for prison staff, with the goal of more successfully helping incarcerated people reintegrate into society.

“Overcrowding, violence, and long sentences are common in U.S. prisons, often creating a climate of hopelessness for incarcerated people, as well as people who work there,” says Jordan Hyatt, a professor of criminology.

Making a prison environment more humane will translate to a more efficient system overall, experts say. And the Norwegian model prioritizes rehabilitation and reintegration over punishment. Safety, transparency, and innovation are considered fundamental to its approach.

Amend, a nonprofit, partnered with four states – California, South Dakota, Oregon, and Washington – to introduce resources inspired by Norwegian principles.

“We find out ... what [an incarcerated person’s] goals and interests are and then we work with them on that, which had never really been happening a lot in restricted housing,” says Washington state’s Lt. Lance Graham. “It’s brought massive changes to the state.”

Can US prisons take a page from Norway? Five questions.

Earlier this year, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a new vision for the San Quentin State Penitentiary, centered on rehabilitation and job training, inspired by another prison system that has halved its recidivism rate – in Norway.

The re-imagining of California’s most notorious prison, infamous for housing the nation’s largest death row population, could prove pivotal in how the United States rethinks rehabilitation and staff wellness within prisons.

About 2 out of 3 Americans released from jails and prisons per year are arrested again, and 50% are re-incarcerated, according to the Harvard Political Review. In Norway, that rate is as low as 20%.

As more U.S. states seek to improve their correctional systems, the Norwegian model could prove key. It aims to create a less hostile environment, both for people serving time and for prison staff, with the goal of more successfully helping incarcerated people reintegrate into society.

Why are U.S. prisons in need of reform?

While the United States makes up less than 5% of the global population, its prison system holds approximately 20% of the world’s total prison population. And even though it’s been on a slight decline since 2008, the total population of incarcerated Americans has increased by 500% since 1970, according to The Sentencing Project.

“Overcrowding, violence, and long sentences are common in U.S. prisons, often creating a climate of hopelessness for incarcerated people, as well as people who work there,” says Jordan Hyatt, associate professor of criminology and justice studies at Drexel University.

Correctional employees experience some of the highest rates of mental illness, sleep disorders, and physical health issues of all U.S. workers, a 2018 Lexipol report found.

Nearly 19% of prison workers reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder – a rate six times higher than that found in the general population. Moreover, 100% of correctional officers were exposed to at least one VID (violence, injury, death) event during their career, according to a 2011 survey by the Department of Justice.

So why try Norway’s model?

Making a prison environment more humane will translate to a more efficient prison system overall, experts say. And the Norwegian model prioritizes rehabilitation and reintegration over punishment. Safety, transparency, and innovation are considered fundamental to its approach. Core practices aim to create a feeling that life as part of a community continues even behind walls and bars, says Synøve Andersen, postdoctoral research criminologist at the University of Oslo.

In some Norwegian prisons, incarcerated people wear their own clothes, cook their own meals, and work in jobs that prepare them for employment, says Dr. Andersen. They have their own space, too, since single-unit cells are the norm. “There is a goal to provide people living in a unit together with a shared common space with a kitchen, washer and dryer, and lounging space,” she says.

While critics argue that people in prison should not have access to daily comforts, Dr. Andersen disagrees. “Imprisonment, the deprivation of liberty itself, that is the punishment.”

Instead, while they are separated from society, incarcerated people should experience normal, daily routines so they can have increased opportunities to reform without being preoccupied with fear of violence from other inmates, she argues.

What does this mean for prison guards?

The principle of dynamic security means correctional officers also must have more complex social duties besides safety and security, including actively observing and engaging with the prison population, understanding individuals’ unique needs, calculating flight risks, and developing individualized treatment plans.

Washington state’s Lt. Lance Graham works within restricted housing and solitary confinement units, an environment he says lacks empathy and connection with those incarcerated. “We never had the opportunity to connect with the people in our care.”

But when visiting Norway’s isolation units, he saw their staff was much more engaged with the prison population – and was much happier.

“This program really promotes staff wellness, changing the relationship that you have with the people in your care,” says Lieutenant Graham. “So you’re not going to have as many instances of fight or flight syndrome in your daily work. You reach common ground and talk like normal folks.”

“If you actually want to change the prison environment, invest in staff,” says Dr. Andersen. “They’re there all the time. They’re doing the work.”

Who is trying the Norwegian model?

Amend, a nonprofit from the University of California, San Francisco, partnered with four states – California, South Dakota, Oregon, and Washington – to introduce resources inspired by Norwegian principles and sponsor educational trips to Norway for U.S. correctional leaders.

At California’s San Quentin, Governor Newsom hopes to emphasize inmate job training for high-paying trades such as plumbers, electricians, or truck drivers. His budget proposal allocates $380 million to repurpose a factory into a center for innovation focused on providing social services and breaking cycles of crime. Mr. Newsom aims to complete the project before he leaves office in 2025.

In Washington state, prison staff began developing supportive working relationships with the incarcerated in their care by developing individual rehabilitation plans.

“Basically, we find out as a person, what their goals and interests are and then we work with them on that, which had never really been happening a lot in restricted housing,” says Lieutenant Graham. “So it’s brought massive changes to the state.”

In North Dakota, former Director of Corrections Leann Bertsch says after revamping the training and responsibilities of prison officers, interactions between staff and inmates felt respectful and calmer.

“Instead of getting as many grievances from the resident population, I started getting what we call positive behavior reports on our staff. ... I think it really helped shift the culture to one that’s more restorative versus punitive,” says Ms. Bertsch.

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections collaborated with the Norwegian Correctional Services to pilot Little Scandinavia, a transformed housing unit operated at half the regular capacity to allow for individual cells. The on-duty officers at Little Scandinavia have reported enjoying their work much more now and there haven’t been any reports of violence since its opening in May 2022, says Dr. Andersen.

What are the limits of adopting the Norwegian system in the U.S.?

Norway receives much attention for its low rate of recidivism, but some experts disagree on the measure as a rate of success. “[Recidivism] is not just a product of the correctional system. It has everything to do with your social safety net, your network, your support structure, and your job opportunities,” said Dr. Andersen.

Also, the physical dimensions and layouts of prisons differ drastically between the U.S. and Norway. Instead of large, centralized prisons in the U.S., Norway utilizes a system of small, community-based correctional facilities that focus on rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

While 8% of prisons in the U.S. are private prisons, according to the National Institute of Corrections, all Norwegian prisons fall under the public sector, and some collaborate with nongovernmental and volunteer organizations to provide services to people.

The changes being piloted in U.S. prisons “are not generally incremental,” says criminologist Dr. Hyatt. “They are holistic and they are pervasive.”

“All of these projects that are growing around the country show us so many different ways of re-contextualizing prisons. And there is a lot of optimism in that.”

Difference-maker

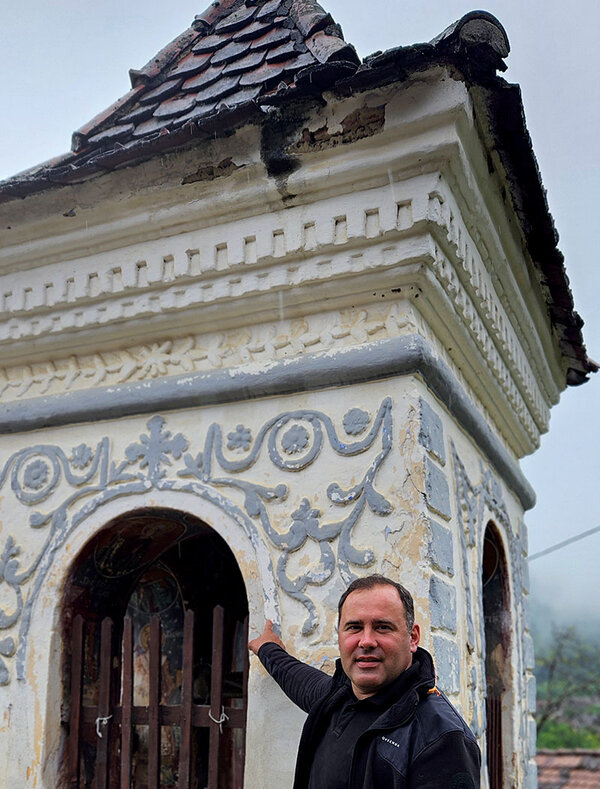

How an ‘Ambulance for Monuments’ is preserving Romanian culture

Romania’s cultural heritage is crumbling, so one man is bringing Romanians together to fix it – local craftspeople to build and restore, community members to provide food and support. The result is not just historical preservation, but also national pride.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Once bustling with families and culture, Eugen Vaida’s home region in Romania had become a string of largely empty villages surrounding abandoned stone churches.

But his group, Ambulance for Monuments, is organizing village craftspeople and students from the city to work together and restore structures such as the 18th-century Romanian Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas of the Hierarch in the mountainous Transylvanian village of Fântânele. And the impact will ripple far beyond the building itself.

“People are starting to understand the value of heritage,” Mr. Vaida says.

For the past seven years, he’s been driving around the country with a van equipped with tools and volunteers in a race against time to rescue endangered historic buildings. He has helped save more than 55 historical structures on the verge of collapse, from medieval churches and fortification walls to old watermills and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. He does so by impressing preservation methods and mindsets onto local communities.

“I wanted to reconnect the members of the community to their roots,” Mr. Vaida says, “make them aware that those buildings are part of their cultural identity, and show them how they can continue the work we do.”

How an ‘Ambulance for Monuments’ is preserving Romanian culture

It is midday on a damp Friday. Eugen Vaida guides his team into the final phase of re-tiling the roof of a church, at the crest of a forested hill in this mountainous Transylvanian village.

Village craftspeople and students from the city meticulously lay tiles on the roof timbers of the 18th-century Romanian Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas of the Hierarch. From the scaffolding, students respectfully and attentively watch Nicolae Gabriel Lungu, who is descended from a Romani family who all knew this skill. Soon an older woman summons the crew to share in a platter of clătite, thin cheese-filled crepes.

Once bustling with families and culture, Mr. Vaida’s home region had become a string of largely empty villages surrounding abandoned stone churches. But now, watching this group interact, he has newfound hope. The repair by his group, Ambulance for Monuments, will help safeguard the church’s stunning outer frescoes. And the impact will ripple far beyond the building itself.

“People are starting to understand the value of heritage,” Mr. Vaida says. For the past seven years, he’s been driving around the country with a van equipped with tools and volunteers in a race against time to rescue endangered historic buildings. He has helped save more than 55 historical structures on the verge of collapse, from medieval churches and fortification walls to old watermills and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. He does so by impressing preservation methods and mindsets onto local communities.

“I wanted to reconnect the members of the community to their roots, make them aware that those buildings are part of their cultural identity, and show them how they can continue the work we do,” he says.

Mr. Vaida offers a “best-practice example of how, with not so much effort, you can save the identity of Romania as a country,” says Ciprian Stefan, director of the ASTRA Museum, Europe’s largest open-air ethnographic museum, in Sibiu.

Architectural heritage in disrepair

Romania’s rich cultural legacy of painted churches and fortified villages was shaped over centuries. But close to 600 historic monuments are in an acute state of degradation, victims of years of dictatorship, poor legislation, and plain neglect, experts say.

Mr. Vaida experienced the destruction in a very personal way. He grew up playing with Romani and Hungarian friends, as well as the German Saxons who had literally built the region. When the 1989 collapse of communist dictatorship flung Romania’s doors wide open, half a million people left. The mass exodus tore the Romanian soul apart – and fractured Mr. Vaida’s own identity. Ambulance for Monuments is an attempt to reclaim both his identity and that of his country.

After his village emptied, he coped by diving into Romania’s traditional customs. He collected artifacts. Traditional dancing rooted him. But he, too, left for the city, to get an education, and he became a successful architect in Bucharest. But six years into the job, he quit to return home. The big city was not his future; his home village was.

He soon discovered that many village craftspeople who had passed on their know-how from generation to generation had left for Western Europe. Those who returned came back imitating what they saw abroad, seemingly unaware that things like PVC window frames and industrial tiles could hurt a building’s health in the long run.

Building “new” and “modern” was in vogue, a matter of prestige. Rather than designing homes for strangers, Mr. Vaida wanted to use his architectural skills to save his region’s extraordinary architectural and cultural heritage. He started by teaching children about local history.

But saving historic buildings required more than awareness. Romania needed architects trained in historical preservation and restoration. So in 2016, he launched Ambulance for Monuments in hopes of connecting architectural students, craftspeople, and communities around a new effort to restore decaying historic buildings.

The program follows “a simple recipe,” he says. Volunteer students get hands-on practice in historical restoration; local craftspeople get jobs; and communities help house and feed the teams, and donate the material. And the three groups learn from one another. “It’s going from grassroots up, from down to up,” says Mr. Vaida.

The program has since grown, recruiting some 800 volunteers annually.

A model by example

Key to Mr. Vaida’s success has been impressing upon locals the importance of preservation efforts with his own generosity and dedication.

“He doesn’t go to villagers to ask for anything, but he goes there to give something,” says Mr. Stefan. “The community stays in the shadows at first. When they see Eugen comes with material and manpower to restore their church, they say, ‘Let’s help him,’ and, little by little, they come and help with housing, with food, and they say, ‘We have a craftsman in the village who knows how to chop the wood,’ for instance.”

Gifted with a deep sense of the Romanian rural environment and an ability to talk to all its actors, from the priest to the villagers, he’s inspired locals to “develop small engines for local development through this heritage,” Mr. Stefan adds.

The task of rescuing Romania’s cultural legacy is huge, but Mr. Vaida sees signs of progress. Partly as a result of his group’s work, the law was changed, making it easier to tackle emergency projects. Some of Romania’s regions devote more money to preserving old monuments. And Mr. Vaida is proud of his project’s popularity among young people, mostly architectural students.

“People are moving back to the villages of their grandparents, because they feel they belong there,” he says. “They are rediscovering old houses, their heritage, their villages, and are getting involved in the preservation of this type of living.”

His work has earned broader recognition as well. In 2020, Mr. Vaida won an award from Europa Nostra, a European heritage protection initiative. That award prompted congratulations from King Charles III of the United Kingdom, who called Mr. Vaida’s work “an inspiration for like-minded people in other countries to follow.”

Confronting mistrust

After a hard day’s work of restoration in Fântânele, Mr. Vaida has invited the entire village to a workshop on jiana, his region’s traditional folk dance. The mayor and two Orthodox priests have come to show their appreciation. The appreciation wasn’t always there. Just after moving to the village during the pandemic, Claudia Maior found local authorities were about to redo the roof of the historical-listed church with industrial tiles. She invited Mr. Vaida to speak to local authorities and villagers about the help his project could offer, but mistrust was deep-seated at first.

“Villagers didn’t understand why the Ambulance didn’t ask for money in return,” she says. In the upheaval of the post-dictatorship years, corruption was rampant, as was mistrust of officials. “People used to give something in order to receive something,” she says.

But eventually the village rallied to the idea and welcomed Mr. Vaida’s team.

“What Eugen is doing is huge awareness-building on how beautiful our heritage is, and how good we can feel if we include what we inherited and not only new things,” says Gabriela Hila, who decided to move to Fântânele during the pandemic. “Eugen is a Romanian from a very Romanian village, and the fact that he is willing to intervene in a Hungarian church or Saxon one is what makes him special.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

An invisible force in the Israel-Hamas war

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The front lines of the war in Gaza are not always the military front lines. Also present in the intense fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas militants is an invisible force known as the “rules of war,” backed up by international law.

While often ignored by combatants, these rules nonetheless have probably shaped the war in the treatment of civilians, hostages, captured fighters, and detainees. For evidence of these laws in action, just note the visit to Gaza on Tuesday by Mirjana Spoljaric, president of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

As the world’s leading neutral intermediary and custodian of the Geneva Conventions, the ICRC has used confidential dialogue with both sides to help set up a temporary truce and exchanges of hostages and prisoners. Last month, the Red Cross president met Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh in Qatar to “advance humanitarian issues.” She was in Gaza yesterday to de-escalate tensions and further promote respect for the rules of war aimed at protecting the innocent.

An invisible force in the Israel-Hamas war

The front lines of the war in Gaza are not always the military front lines. Also present in the intense fighting between Israeli forces and Hamas militants is an invisible force known as the “rules of war,” backed up by international law.

While often ignored by combatants, these rules nonetheless have probably shaped the war in the treatment of civilians, hostages, captured fighters, and detainees. For evidence of these laws in action, just note the visit to Gaza on Tuesday by Mirjana Spoljaric, president of the International Committee of the Red Cross.

As the world’s leading neutral intermediary and custodian of the Geneva Conventions, the ICRC has used confidential dialogue with both sides to help set up a temporary truce and exchanges of hostages and prisoners. Last month, the Red Cross president met Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh in Qatar to “advance humanitarian issues.” She was in Gaza yesterday to de-escalate tensions and further promote respect for the rules of war aimed at protecting the innocent.

She has not been alone in representing the institutions of humanitarian law. The prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, Karim Khan, was in Israel and the West Bank in recent days, encouraging both Hamas and Israel to avoid war crimes and provide aid to civilians.

He said the atrocities committed by Hamas on Oct. 7 were “some of the most serious international crimes that shock the conscience of humanity.” And he advised Israel that “this is the time to comply with the law. If Israel doesn’t comply now, they shouldn’t complain later.”

Changes in the nature of war have required the ICRC and the ICC to keep adapting the universal principles behind the Geneva Conventions and similar international laws. Yet the ICRC has also lately tried to highlight the positive examples of compliance with such laws. “Collecting such examples and transforming them into lessons learned for militaries and armed actors more generally will become more important,” Peter Maurer, the recent president of the ICRC, told the International Review of the Red Cross last year.

The ICRC’s work is driven by what it calls “fundamental principles,” such as impartiality during a war to protect innocent people and help heal wounded people. “Principles are particularly important, because of the complexity of situations we are navigating,” said Dr. Maurer.

And nothing is more complex than the war in Gaza, in which those who represent humanitarian law are providing an invisible force making sure this war has limits and the innocent have the right of protection.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Always free

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

Considering our innate goodness and wholeness as God’s children opens the door to healing.

Always free

Who doesn’t crave freedom in their life – whether from illness, fear, or something else?

Christ Jesus offered this encouragement: “If ye continue in my word, then are ye my disciples indeed; and ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:31, 32).

This promised freedom isn’t limited to some vague time in the future. It’s a promise for right here and now. The truth that heals is the fundamental fact that we are not mortals with problems, but entirely spiritual – God’s children. We’re designed to eternally reflect God, Spirit, who is perfect.

One time I asked God in prayer for inspiration that would bring freedom from leg pain that was bothering me. “You already are free,” was the immediate and potent answer. As I considered that revolutionary thought for a few minutes, the pain disappeared completely and permanently.

Man – meaning all of us in our true, spiritual nature – is already free. We reflect God’s wholeness and goodness. That’s what Jesus proved throughout his healing ministry. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, wrote, “The Christlike understanding of scientific being and divine healing includes a perfect Principle and idea, – perfect God and perfect man, – as the basis of thought and demonstration” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 259).

To understand, through the power of Christ – God’s healing message of truth and love – that we are already spiritually free can be transformative and redeeming. This is the salvation that comes to us from God, divine Love, in a way that we can both understand and experience. Our spiritual sense, given to us by God, enables us to discern – even when circumstances indicate otherwise – that not only are we already free, but we always have been.

In the Bible, Paul, whose own character was thoroughly reformed through Christ, wrote, “There is therefore now no condemnation to them which are in Christ Jesus, who walk not after the flesh, but after the Spirit. For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death” (Romans 8:1, 2). Freedom is an irrevocable, holy law of God. Recognizing this opens our eyes to see and experience that freedom more tangibly, even where it feels as though we are stuck.

Science and Health gives this insight, using the biblical name “I AM” to refer to God: “The everlasting I AM is not bounded nor compressed within the narrow limits of physical humanity, nor can He be understood aright through mortal concepts” (p. 256). And neither can God’s idea, man, be “bounded or compressed” as His reflection! I’ve frequently found that praying from the standpoint that God’s children are forever free, forever safe, and forever well brings freedom from physical as well as mental captivity.

No matter what kind of circumstance or condition threatens, there’s a path to healing in Christ Jesus’ promise mentioned above. As we embrace the spiritual truth that we already and always are free, this understanding brings about help and healing.

Viewfinder

Eyelash icicles

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. And we’ve got plenty to share about tomorrow, including the Biden administration turning up their demands to Israel to safeguard Palestinian citizens. Is Israel listening? Columnist Ned Temko will also explore how, at the end of the day, a two-state solution is the only viable path to peace.

We’ll also have a suite of graphics to offer a deeper look into the COP28 climate summit, a look at Nikki Haley’s place in the presidential race, and the joy of five new children’s books. We hope to see you back.