- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The Monitor’s weekly political wrap-up

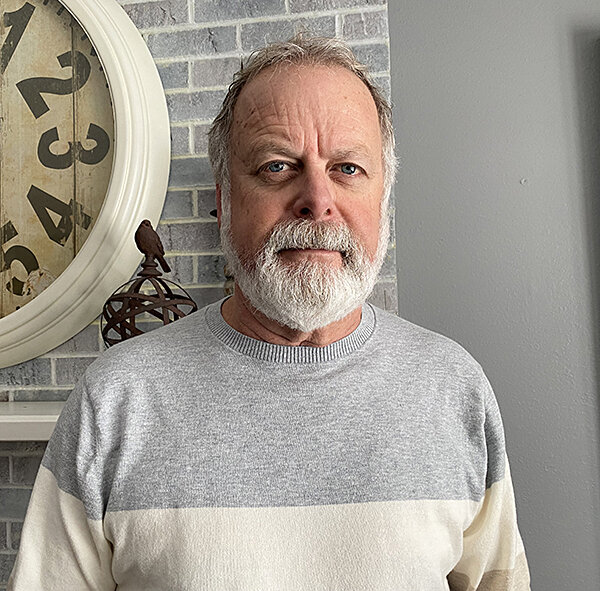

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

We’re in the groove of trying new things, so our politics team had an idea. So much has happened this week, both in political news and with our reporters on the ground in Iowa. It’s hard to keep track of it all. What if we did an end-of-week wrap-up?

So we did. You can read it here. You’ll find links, bonus analysis, and a peek behind the curtain to get a close-up look at how our journalism is made. Let us know what you think, and if you’d like this as a regular feature. Please email me at editor@csmonitor.com.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Big hurdle for Trump rivals in Iowa: A party realigned

During the Trump era the Republican Party has transformed, with its politics now dominated by non-college-educated voters. That has big implications for this year’s election.

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

Nikki Haley has made Steph Herold feel excited about a presidential candidate “for the first time in a long time.”

The former South Carolina governor speaks to Ms. Herold’s concerns about fiscal responsibility and military preparedness. Ms. Haley brings years of political experience to the job. Perhaps most important, she “doesn’t dis or talk badly about people.”

A retired graphic designer and lifelong Republican voter from the Des Moines suburbs, Ms. Herold voted in 2016 and 2020 for Donald Trump. But she was never really a Trump fan. “He just happened to be our candidate,” she says.

As Iowa’s Republicans prepare to caucus for their party’s nominee on Monday, they will also begin shaping the future direction of their party. Polls show Mr. Trump holds a dominant lead, with the strongest support coming from Iowans with a high school diploma or less. Ms. Haley, by contrast, performs best among those with advanced degrees, like Ms. Herold.

Mr. Trump’s supporters could define the GOP in an even more populist mold, should Mr. Trump prevail. Or higher-educated, previously reluctant Trump voters could potentially still nudge the party in a different direction.

“Parties ebb and flow, and I think that’s good. You have to change with the times,” says Ms. Herold. “I look at myself: From 19-year-old me, goodness gracious, I’ve changed – and that’s good.”

Big hurdle for Trump rivals in Iowa: A party realigned

Nikki Haley has made Steph Herold feel excited about a presidential candidate “for the first time in a long time.”

The former South Carolina governor speaks to Ms. Herold’s concerns about fiscal responsibility and military preparedness. She brings years of political experience to the job. Perhaps most important, she “doesn’t dis or talk badly about people.”

A retired graphic designer and lifelong Republican voter, Ms. Herold comes from a long line of Iowa conservatives: Her father, Bob Van Vooren, was Ronald Reagan’s state campaign chair. Over the past two decades, she voted for George W. Bush, John McCain, and Mitt Romney. And in 2016 and 2020, she voted for Donald Trump.

“That’s not something I like to tell people,” she says, laughing nervously from her home in a West Des Moines suburb, where she’s babysitting her granddaughter. A Haley sign sticks out of her snowy front yard. “I was never a Trump supporter; he just happened to be our candidate. For the life of me, I’m not even sure how he made it through.”

Iowa GOP caucus victories used to be built on voters like Ms. Herold. That all changed, however, in 2016, when “we saw one of the biggest realignments in American political history,” says New Hampshire GOP strategist Matthew Bartlett. With his unconventional populist campaign, Mr. Trump upended years of Republican orthodoxy and expedited a great scrambling of the two parties’ electorates, bringing a flood tide of white, working-class voters – a onetime staple of the Democratic Party – into the Republican fold.

These voters have given Mr. Trump a powerful base of support in Iowa. Just days before Monday’s vote, a new Suffolk poll finds Ms. Haley has moved into second place, but is still running more than 30 points behind the former president. Notably, Mr. Trump’s strongest support comes from Iowans with a high school diploma or less, whereas Ms. Haley performs best among those with advanced degrees, like Ms. Herold.

This divide along education lines gives Mr. Trump a distinct advantage, since there are more voters without college degrees than with. (It also helps explain why the race is much closer in New Hampshire, which has a higher percentage of college-educated voters.)

But while the GOP will likely never go back to being the party it once was, it also won’t be the “party of Trump” forever. And every four years, parties redefine themselves, in one way or another. Mr. Trump’s dominance among working-class voters, which surveys suggest may now be extending to some voters of color, could shape the party’s identity in an even more populist mold this cycle. Or higher-educated, previously reluctant Trump voters – tired of the drama, or frustrated by new abortion restrictions, or worried about winning in the November general election – could start to nudge things in a different direction.

“Parties ebb and flow, and I think that’s good. You have to change with the times,” says Ms. Herold. “I look at myself: From 19-year-old me, goodness gracious, I’ve changed – and that’s good.”

Willie Glosser’s shift

During the final days of the campaign here in Iowa, hundreds of voters have been tracking snow into pubs and event halls to see Ms. Haley or Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, who is competing with her for second place in the polls. Many say they’re specifically looking for a Republican who isn’t Mr. Trump.

But their numbers pale in comparison with the thousands of Trump supporters lining up in freezing temperatures for hours ahead of his rallies.

“I don’t think there’s anything that could happen to keep Trump from being the Republicans’ nominee,” says Willie Glosser, a subcontractor who lives in Indianola, a city south of Des Moines, and is married with 10 children. Both Mr. DeSantis and Ms. Haley seem like strong candidates, he allows, “but neither of them are Trump.”

Before 2016, Mr. Glosser, who never attended college, didn’t really pay close attention to politics. He voted in most presidential elections, mostly for Republicans, “but not all the time.” He watched with only mild interest as Mr. Trump launched his first run for president. Soon, however, he found himself all in.

Mr. Glosser had always wondered about government corruption and had concerns about what was happening at the U.S.-Mexico border. All of that “got illuminated” when Mr. Trump came on the scene. Mr. Glosser started attending Trump rallies and watching debates for the first time. He even hosted candidate forums for school board and sheriff at his house.

“Trump not only says he fights for the little guy – I believe we saw it,” says Mr. Glosser, who voted for Mr. Trump in the 2016 and 2020 general elections and plans to attend his first caucus on Monday. “He had the ability to make us feel important to him.”

In 1992, when Democrat Bill Clinton ousted Republican George H.W. Bush from the White House, 55% of voters whose education ended with high school identified as Democrats, while the GOP was home to more college graduates. Three decades later, those numbers have reversed. Fifty-one percent of the Democratic electorate nationwide in 2022 held either a college or postgraduate degree, compared with just 37% of Republicans.

“I think [Mr. Trump] has awakened a new portion of people out there who have never been a part of the process and felt neglected,” says Ms. Herold, who’s wearing a sweatshirt from her alma mater, Iowa State (“Go Cyclones!” she says). “They have felt like, ‘Nobody cares about us,’ and for some reason they think Trump does.”

Balancing act for Haley

Ms. Haley’s candidacy is staked on the hope that strong support from college graduates, along with some Trump-weary voters from the party’s working-class base, will make for a winning combination. But it’s a difficult balancing act.

At an event Thursday in Ankeny, a suburb north of Des Moines where the median household income is over $100,000 and 98% of residents have a college degree, Ms. Haley delivered the same careful stump speech that she’s laid out across the Hawkeye State (though mostly in Des Moines and its suburbs).

“I think President Trump was the right president at the right time to break the things that we needed,” said Ms. Haley, to roughly 200 voters in an event space strung with bistro lights. “I agree with a lot of his policies, but rightly or wrongly, chaos follows him.”

Some in the room of well-dressed Iowans (men in button-down shirts and sweaters with elbow patches, women carrying Louis Vuitton bags) nodded in agreement. More than half the people in the room raised their hand when asked if they were seeing Ms. Haley for the first time.

Critics have accused Ms. Haley, as well as Mr. DeSantis, of being unwilling to attack Mr. Trump forcefully enough. Former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who exited the GOP presidential field this week, said flatly that any candidate too afraid to call Mr. Trump “unfit” to be president was “unfit themselves.” He was also caught on a hot mic predicting that Ms. Haley will “get smoked.”

But to Mr. Bartlett, the New Hampshire strategist, the former United Nations ambassador needs a broad strategy to have any hope of capturing a majority in today’s GOP.

“In order to [win],” he says, “Nikki Haley is going to need everyone.”

Today’s news briefs

• Red Sea strikes: U.S. and British militaries strike more than 60 targets in Yemen in retaliation for attacks by the Iranian-backed Houthi militant group against maritime vessels in the Red Sea.

• Taiwan election: The island prepares to elect a new president and legislature Jan. 13. Many see the election as a test of control with China, which claims the self-governing republic.

• Jackson water crisis: Residents of Jackson, Mississippi, must boil tap water after traces of bacteria have been found in public drinking water. The state capital’s water system has faced chronic problems.

• Winter storms: Snow is expected in Portland, Oregon, a city more accustomed to rain, with “life-threatening wind chills” nearing South Dakota and the possibility of tornadoes in the South.

What Palestinians see in genocide hearings

Many Palestinians in the West Bank say the case brought by South Africa against Israel at the International Court of Justice could prompt judges to order a cease-fire in Gaza, offering a rare glimmer of hope for relief amid a bleak war.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Fatima AbdulKarim Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

For a moment, Palestinians glued to TVs or mobile phones watching live updates of the Israel-Hamas war were not witnessing missile strikes or evacuees fleeing fighting. Instead, tens of thousands of people across the West Bank were watching gowned judges and lawyers in The Hague considering a genocide case brought by South Africa against Israel.

“Even if the final ruling doesn’t go in our favor, we really need this case right now because it can result in a cease-fire [soon],” says Nael Abu Dheim, a mechanical engineer, at a Ramallah rally thanking South Africa for filing the case.

The Israeli government has dismissed the Hague case as an “absurd blood libel,” and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken criticized the case Tuesday, calling the charge of genocide “meritless.”

The Palestinians’ hope is blunted by skepticism. Najwan Jadallah, an assistant professor at Palestine Technical University, echoes many Palestinians’ doubts that any court ruling in their favor would ever be implemented or would change things on the ground.

“International law has not been enforced before,” he says. “We don’t believe it will be enforced now.”

What Palestinians see in genocide hearings

For a moment, for the first time since Oct. 7, Palestinians glued to TVs or mobile phones watching live updates of the Israel-Hamas war were not witnessing missile strikes or evacuees fleeing fighting.

Instead, tens of thousands of people across the West Bank – in living rooms, in cafes, and regularly checking their phones at work – were watching the proceedings in a wood-paneled courtroom in The Hague filled with gowned judges and lawyers considering a case brought by South Africa against Israel.

“Even if the final ruling doesn’t go in our favor, we really need this case right now because it can result in a cease-fire [soon],” says Nael Abu Dheim, a 51-year-old mechanical engineer, at a Ramallah rally thanking South Africa for filing allegations of genocide against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

South Africa’s complaint, arguing that Israel’s ongoing military offensive in the Gaza Strip and failure to protect civilians constitutes genocide, is being watched closely by Palestinians.

The controversial case, which wrapped up its initial two-day public hearings Friday, could prompt judges to order a cease-fire in Gaza.

Many Palestinians in the West Bank see that as a rare glimmer of hope for relief from humanitarian suffering amid a bleak war and, apart from the war, the most violent year in the occupied territories in two decades.

But such hope is blunted by skepticism, born of what they see as decades of failures by the international community to enforce United Nations resolutions on the ground in the West Bank and Gaza.

The Israeli government has dismissed the Hague case as an “absurd blood libel” and a “despicable and contemptuous exploitation of the Court.”

The case, filed Dec. 29 by South Africa, alleges that Israel has violated the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in its war with Hamas in Gaza, restricting food and water supplies to the besieged enclave and killing thousands of Palestinian civilians.

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken criticized the case Tuesday, calling the charge of genocide “meritless.” Last week, White House National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby described South Africa’s submission as “counterproductive and completely without any basis in fact.”

Israel, a signatory to the genocide convention, is engaging with the court to contest the case. Retired Justice Aharon Barak, former president of Israel’s Supreme Court, is serving as a judge on the ICJ panel.

Israel alleges the ICJ case is serving as “cover” for Hamas’ imprisonment of Israeli civilian hostages and barrages of missile fire targeting Israel.

No matter the final ruling, Palestinians hope the 84-page submission will convince the court to issue a “provisional measure” this month ordering Israel to suspend its military operations in Gaza so as to facilitate fact-finding missions and preserve evidence in the case – a court-ordered cease-fire.

Political leverage

Israel’s defense team warned Friday that such “provisional measures would stop Israel defending its citizens; more citizens could be attacked, raped, and tortured.”

At Friday’s session, Omri Sender, a member of Israel’s legal team, said Israel is working with a senior U.N. coordinator to “map the needs of future returns of Palestinians to northern Gaza,” which “shows that Israel remains bound by its international and legal obligations, especially as a party to the genocide convention.”

The Palestinian Authority, which governs the West Bank, sees the ICJ case as offering potential leverage. Officials say any provisional decision could help pressure the Israeli government to wind down its operations in Gaza and fast-track a political resolution by which the PA would return to the coastal enclave, currently ruled by rival Hamas.

“The aim is tactical, a provisional ruling within two weeks that would result in an immediate cease-fire,” says Shawan Jabarin, director of the Palestinian human rights watchdog Al Haq. It would be much more difficult, he acknowledges, to prove Israeli intent to commit genocide.

Palestinian legal advocates view South Africa’s involvement as key. Had the submission come from the Palestinians, or from an Arab state, “it would have been a case, once again, of Palestine versus Israel, rather than what it really is, which is a question about [whether] genocide occurred and if the world will stop it,” says veteran lawyer Diana Buttu.

But there is a feeling of incredulity among Palestinians that it took an African nation some 4,000 miles away to pursue international law on their behalf.

“South Africa has shown more courage than Arab and Muslim leaders by taking up the claim on behalf of Palestinians,” says Bilal Abu Samra, a Ramallah merchant.

As a sign of appreciation, dozens of Palestinians braved cold and wet winter weather Wednesday and Thursday, gathering at a statue of Nelson Mandela in Ramallah, waving Palestinian flags and holding up signs quoting the anti-apartheid icon.

Experience fuels doubts

But their hopes were muted by experience. Several demonstrators pointed out that Washington has vetoed U.N. Security Council resolutions calling for a cease-fire, and that Israel has ignored U.N. rulings in the past.

They cited a 2004 World Court advisory opinion declaring Israel’s separation wall, cutting off the West Bank from Israel, to be illegal; the wall is still there. Last month the Security Council called for safe, unhindered, and scaled-up distribution of humanitarian aid to the Gaza Strip, which has not occurred.

Najwan Jadallah, a 45-year-old assistant professor at Palestine Technical University, echoes many Palestinians’ doubts that any court ruling in their favor would ever be implemented or would change things on the ground.

“Even if the court orders a cease-fire, will Israel commit to it?” he wonders. “For decades, we have been under occupation and watching our own people killed. International law has not been enforced before; we don’t believe it will be enforced now.”

“I don’t believe anyone can stop Israel,” adds Mr. Abu Samra, the merchant. “I am not hopeful that this case will be more than symbolic.”

On Friday the ICJ adjourned for deliberations, with a decision expected this month on whether to issue an interim cease-fire order or not.

Letter from Berkeley: Requiem for People’s Park

People’s Park – Berkeley’s iconic gathering spot, founded in the 1960s – sits on valuable real estate in the heart of the university town. Plans to develop on the site raise questions about public space and what’s best for a community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Billy Simpson can’t imagine Berkeley without People’s Park. The iconic park in this California college town was where he grew up playing. “That park is like, it’s freedom,” says Mr. Simpson. “It’s just love.”

Shipping containers now line the park’s perimeter, blocking public access. A decadeslong power struggle over the best use of People’s Park came to a head last week, when the University of California, Berkeley, the park’s owner, cleared it of unhoused residents and erected the container wall.

The move secures the site for a university housing development, long held up by protests, vandalism, and legal challenges.

“We are going to open up a beautiful building and a beautiful new public park space that will be for the enjoyment of everyone,” says Kyle Gibson, a UC Berkeley spokesperson.

That vision faces opposition and doubters. Many locals now feel squeezed out. And nearby shop owner Al Geyer sees the new development as part of an effort to “defunkify” Berkeley.

Still, the park’s zeitgeist of acceptance is what defenders hold to.

“They can’t build the wall between us,” says Jen, a local resident who did not give her last name, citing privacy concerns. “Because we’ve already created these connections.”

Letter from Berkeley: Requiem for People’s Park

Billy Simpson can’t imagine Berkeley without People’s Park. The iconic park in this California college town was where he played growing up. As he got older, he made some of his best friends there. When he worked in food delivery, he would bring canceled orders to unhoused residents who found rest there.

“That park is like, it’s freedom. It is what Berkeley used to be,” says Mr. Simpson. “It’s just love.”

People’s Park inspired Krista McAtee to attend the University of California, Berkeley three blocks away. The fifth-year student gets emotional recalling her first visit as a 13-year-old on a campus tour with her family. She returned home to Southern California, decorated a jean jacket with “power to the people,” and set her sights on the school.

“This idea of community, this idea of taking care of one another,” says Ms. McAtee, “are values that I learned from being at People’s Park.”

Shipping containers line the park perimeter now, blocking public access. A decadeslong power struggle over the best use of People’s Park came to a head last week, when UC Berkeley, which owns the park, cleared it of unhoused residents and erected the container wall. The move secures the site for a long-planned university housing development that has been held up by protests, vandalism, and legal challenges.

“This is not a forever installation,” says Kyle Gibson, a UC Berkeley spokesperson. “This is going to be here through construction, and when we are done, we are going to open up a beautiful building and a beautiful new public park space that will be for the enjoyment of everyone.”

That vision faces opposition and doubters. But tension has always been part of the park’s origin story.

Everyone welcome

People’s Park emerged in 1969, two years after the university bought it for dorm space and then left it vacant. A local paper suggested people should meet there, and they did. It became a community gathering place; people put in gardens, a pond, and a playground. But the school tore it all out a month later, leading to protests that culminated with then-Gov. Ronald Reagan sending in the National Guard.

Throughout the years, the university made sporadic attempts to regain control of the park, but it remained open to the community. People’s Park became a refuge – for protesters, philosophers, artists, students, residents housed and unhoused. It was a place where anyone who needed it could go for help.

“There’s a very big lack of community spaces in the modern age. And that’s what People’s Park used to be,” says UC Berkeley student Esther Choi. “Now it’s gone.”

That demise has weighed on advocates for the housing development, too, which include Berkeley’s mayor, City Council, and state lawmakers. The plan took five years to develop, with input from local organizations, neighbors, students, and officials. “The park represents many things to many people,” says Mr. Gibson, who points out that plans “reflect that history in the new design.”

Today the 2.8-acre park is on the National Register of Historic Places, surrounded by historic homes and churches noted for their architecture.

Plans for the new development include 1,100 student housing units and more than 100 supportive housing units, while preserving 60% of the open space. They also commemorate the park’s history and offer unhoused residents transitional housing, a community-led drop-in center, and a dedicated social worker. Construction is on hold while the state Supreme Court considers whether it violates environmental regulations.

Everyone agrees there’s a critical need for housing. University enrollment is up 26% compared with 10 years ago, and rising costs have added to the squeeze. The People’s Park project is part of a broader school initiative to double student housing with 9,000 new beds across 14 sites throughout the city.

Safety is an issue, too. The park has long provided rest for people with nowhere to go. But during the pandemic, overnight restrictions were lifted, enabling homeless encampments. Crime and drug use increased, although opponents say it’s a challenge the university created through neglect; in the last few years, it closed the park’s public restrooms and removed trash cans, trees, and gardens.

“Who are they kidding?” asks Harvey Smith, president of the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group, referring to Berkeley administrators. “This is an institution that has run three national nuclear laboratories. Who’s going to believe that they actually can’t maintain in beautiful condition the 2.8-acre park? It’s crazy talk.”

Damp hope

Rain drizzled down on Telegraph Avenue earlier this week, adding a chill to the tone of defiance – or resignation, depending on who’s asked - that blankets the park. The avenue runs a block off the park, right up to campus, where many of the shops and restaurants lining the street are entwined with Berkeley counterculture.

Annapurna is one of those iconic shops. Al Geyer opened his store around the time that People’s Park was established, but he, too, feels squeezed out.

He sees the new park development as part of the university’s larger effort to “defunkify” Berkeley amid demographic sea changes. The pandemic gutted retail activity, he notes, providing Berkeley administrators a tipping point. “We lost all the stores, and they’ve done nothing,” he says. “They’re happy to have this as a base moment, where you clean the counter off and you start from scratch.”

Mr. Geyer recalls the park’s early days when he supported it with window displays. Protesters protected his property. “They would stand in front and say, ‘Do not harm Annapurna, because we’re open to the working man, to multiculturalism,’” says Mr. Geyer. Even if parkgoers didn’t buy from him, they were welcome to browse his store or rest out front.

For now, that spirit of acceptance and mutual support is what park defenders are holding on to.

“If it does get taken from us, people will still gather,” says Jen, a local resident who did not give her last name, citing privacy concerns. She works with the park’s mutual aid group. “They can’t build the wall between us because we’ve already created these connections.”

Editor's note: A sentence in this article has been updated to clarify that a source named Jen did not wish to have her last name published.

Podcast

On Mideast desk, fighting fatigue with focus

In war, brutality and humanity coexist. For the Monitor, daily coverage is about more than an accounting of strategic gains and losses. It’s about keeping at the fore the stories of those who are most affected. Our Mideast editor joined our podcast to detail his – and his writers’ – essential work.

Every week, like every day, begins early for Monitor writers and editors covering the conflict in Gaza. A Sunday meeting unites the team across time zones. The collaborative agenda includes coverage planning and wellness check-ins. The exchange of viewpoints.

“We’re a diverse group of people who come to this story from many perspectives,” says Ken Kaplan, the Monitor’s Mideast and diplomacy editor. “But there’s a relationship of trust and respect. And friendship, really.”

There are, of course, reportable news events to consider: The local effect of airstrikes. Civilian efforts to mitigate the effects of extended warfare. The public questioning of political leadership in Israel as well as in Gaza.

“They [all] speak to larger dynamics,” Ken says on our “Why We Wrote This” podcast, “but we are able to deal with that breaking news from a human perspective on the ground.”

Bound up in that: a sense of grounded optimism. “I refuse to accept that the worst outcome should be ordained,” Ken says, reflecting on 38 years of professional exposure to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. That view is shared.

“We have Muslims, Christians, and Jews on this team,” Ken says. “We have Palestinians and we have Israelis. And even though perspectives may differ greatly, we can still agree that facts are facts and people are people. A human narrative of what a real person is enduring has value.” – Clayton Collins, Mackenzie Farkus, and Jingnan Peng

Find story links and a transcript here.

Life at the Hub of War Coverage

Space, love, and poetry: ‘The Nikki Giovanni Project’

A new documentary offers a nonlinear, lyrical look at the activism and life of a celebrated Black poet. What our commentator comes away with is a sense of love and awe.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

It feels deficient to call Nikki Giovanni a poet laureate after viewing her new documentary, “Going To Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project.”

The documentary, which is now streaming on Max, is simultaneously victorious and vulnerable. It offers slivers of Giovanni’s life, focusing on matriarchy, sisterhood, and sexuality. Her poetry is a stargate into the activism of the period, a timeline from past to present and beyond.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, and raised in Cincinnati, Giovanni rose to fame as one of the pioneers in the Black Arts Movement (BAM), which drew heavily from both the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. BAM is a fitting nickname for the “big bang” that would birth the careers of icons such as James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Gil Scott-Heron.

For as much as she is defined for her activism, she also gained crossover appeal through writing children’s books in the 1980s. Her words and presence are a salve for generations. Whether she is recognized as one of the heroes of Harlem at the Apollo Theater, or among Black youth at Afropunk, the commentary is similar: how Giovanni’s poetry gave them the strength to go on.

Space, love, and poetry: ‘The Nikki Giovanni Project’

It feels deficient to call Nikki Giovanni a poet laureate after viewing her documentary “Going To Mars: The Nikki Giovanni Project.” She is much more than her words, which span across the space of Blackness and the endless time it seems to take to secure our civil rights. And yet, the documentary is about not just transmission, but translation – specifically, the uniqueness of how Giovanni views life and the world around her.

The documentary, which is now streaming on Max, is simultaneously victorious and vulnerable. It offers slivers of Giovanni’s life, focusing on matriarchy, sisterhood, and sexuality. Her poetry is a stargate into the activism of the period, a timeline from past to present and beyond.

Born in Knoxville, Tennessee, and raised in Cincinnati, Giovanni rose to fame as one of the pioneers in the Black Arts Movement (BAM), which drew heavily from both the Civil Rights and Black Power movements. BAM is a fitting nickname for the “big bang” that would birth the careers of icons such as James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Gil Scott-Heron.

What brings those slivers together is Giovanni’s unique analysis – with an incisiveness that cuts beyond the bone and to one’s soul. The imagery of her reading “I Married My Mother,” a poem about abuse, trauma, and emotional release, on the radio station WHYY is stunning. The call letters contain an urgent intonation, an inquiry of a higher power:

I know crying

Is a skill

I automatically wipe

My eyes even though I know

Crying

Is a skill

The conversation on the radio delves into her childhood and her abusive father – and how it makes her analysis of Black men tenuous. That dialogue leads into an excerpt of a 1971 conversation between Giovanni and another luminary, Baldwin, which ran as a two-part episode on the television series “Soul!” Ellis Haizlip, who produced and hosted the show, introduced this particular discussion in a way that felt like a metaphor to space, and finding light in the darkness:

“One of the miracles of this universe that we deal with is the way it can use something as cold and gray and as impersonal as an electron. These electrons that fill your television screen to bring you an experience as warm and as rich and as human as the program you’re about to see.”

“I need love,” Giovanni exhorted, because begging was beneath her. Another portion of that interview with Baldwin went viral in 2022. It touched on the intimate relationship between Black men and Black women, and two of the greatest minds of their generation allowed us to see the depths of their joy and sadness.

That love manifests itself in various ways, such as the care and concern from Giovanni’s partner, Virginia, both professionally and personally. When Giovanni and her son, Thomas, restore their relationship, it allows the elder to get closer to her granddaughter, Kai, and her grasp on motherhood is divine – “I am the rain, she is the blossom.”

Matriarchy is also bittersweet, exemplified in the passing of her 94-year-old aunt, Agnes, which thrusts her into the position of being the oldest woman in her family. Like the bouts with breast cancer and seizures that Giovanni speaks openly about, it is clearly jarring and a reminder of mortality.

Giovanni’s presence and versatility also command love. For as much as she is defined for her activism, she also gained crossover appeal through writing children’s books in the 1980s and later became a professor at Virginia Tech. Her words and presence are a salve for generations. We are reminded of this phenomenon repeatedly, whether she is recognized as one of the heroes of Harlem at the Apollo Theater, or among Black youth at Afropunk. The commentary across timelines is similar: how Giovanni’s poetry gave them the strength to go on.

In places, Giovanni’s journey feels like my own. When an image of the NASA logo appeared on the screen, it reminded me of my scholarly past at my historically Black university, Florida A&M. I smiled when a FAMU graduate spoke about how the poem “Nikki-Rosa” inspired her.

Such testimonials are a reminder of the importance of the BAM vanguard. Though she is not named, Giovanni’s compatriot, Sonia Sanchez, appears multiple times in the documentary. Her words first struck me in 2007 on the introduction of a hip-hop record, “Everything Man”:

Listen, listen a man always punctual with his, mouth

Listen to his, revolution of syllables

Scooping lightning from his pores

Keeping time, with his hurricane beat

Asking us to pick ourselves up and become thunder

Sanchez’s powerful prologue inspired me to look into her other works. She was such an influence on me that as a young reporter, I once interrupted a program at another historically Black school – Paine College – to take a selfie with her. When Giovanni spoke about her defection – and later return – to Fisk University in her native Tennessee, the value and sanctity of radical Black spaces was reemphasized.

Speaking of space, with respect to the late Gene Roddenberry, the creator of “Star Trek,” Black folks always knew that space wasn’t the final frontier. Nichelle Nichols knew from the original series, as did Levar Burton in “The Next Generation.” So does Giovanni. “The trip to Mars can only be understood through Black Americans,” read the opening words of the doc. Giovanni takes this metaphor to the next level, saying that if humankind wants to take an intergalactic journey, it should lead with Black women, who are familiar with traversing the unknown and thriving against all odds.

Overall, Giovanni is celestial in this documentary, and we see a poet finally at peace. This serenity is noticeable in her engagement with young people, whether she is blurting out irreverent one-liners in church or sitting with students at Virginia Tech.

“It’s not that we use our talent to tell people what to do. It’s that we use our vulnerability to share the love in our hearts,” she says. “Don’t you think? I really do.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Meekness takes over in Guatemala

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Across Latin America, voters have tossed out one government after another in pursuit of honest governance and economic stability. Now it is Guatemala’s turn. Yet the transfer of power in Central America’s most populous nation may be qualitatively different from those that have come before it elsewhere in the region.

The inauguration of Bernardo Arévalo on Sunday is less a triumph of personal charisma than a manifestation of a deepening democratic mindset among Guatemalans. Arising gradually in local cantons since the end of a civil war 30 years ago, it reflects a fusing of civic virtues and Indigenous Mayan values.

“The democracy experienced in the cantons is more participatory, more meaningful than simply voting in elections,” said Matthew Krystal, an anthropologist at North Central College in Illinois who has spent three decades studying Guatemalan society.

Mayans, Professor Krystal wrote, believe that “what we do well returns good to us.” In his modesty, Mr. Arévalo has signaled that following the wisdom of the people may be the key to leading societies like Guatemala out of patterns of corruption and lawlessness.

Meekness takes over in Guatemala

Across Latin America, voters have tossed out one government after another in pursuit of honest governance and economic stability. Now it is Guatemala’s turn. Yet the transfer of power in Central America’s most populous nation may be qualitatively different from those that have come before it elsewhere in the region.

The inauguration of Bernardo Arévalo on Sunday is less a triumph of personal charisma than a manifestation of a deepening democratic mindset among Guatemalans. Arising gradually in local cantons since the end of a civil war 30 years ago, it reflects a fusing of civic virtues and Indigenous Mayan values.

“The democracy experienced in the cantons is more participatory, more meaningful than simply voting in elections,” wrote Matthew Krystal, an anthropologist at North Central College in Illinois who has spent three decades studying Guatemalan society, in the Prensa Libre newspaper. “Meetings can last for hours. Everyone has the right to speak and many participate. Their decisions carry the legitimacy that comes from an intensive process of listening, debating, thinking.”

According to Dr. Krystal, one Mayan spiritual leader described the approach to seeking consensus as, “They don’t fight, they love each other.”

Since winning nearly 60% of the vote in an August runoff, Mr. Arévalo has faced repeated attempts by the attorney general and others to annul his victory. That none of those efforts succeeded is due largely to a long-underestimated force. Indigenous Guatemalans – particularly Mayan women – have upheld democracy through sustained peaceful protests. Their quiet defiance dovetails with the incoming president’s own sense of leadership.

“Governance is to be ensured not through the capacity of the state to enforce obedience,” he said in a 2017 interview with the Development and Peace Foundation, “but through the will of the people to pledge their allegiance to institutions that represent them and which they thus consider legitimate. ... This involves ‘weaving’ back trust into the social fabric in every sphere of life. Dialogue – active engagement through listening and understanding – has an important role to play in achieving this effect.”

Guatemala’s Constitution allows for only one four-year term. Mr. Arévalo acknowledges that does not give him much time to break the strong bonds of corruption that have weakened the country’s democratic institutions and driven dozens of judges and journalists into exile. But he argues that most of the work of revitalizing governance belongs to the people rather than to their elected officials.

Mayans, Professor Krystal wrote, believe that “what we do well returns good to us.” In his modesty, Mr. Arévalo has signaled that following the wisdom of the people may be the key to leading societies like Guatemala out of patterns of corruption and lawlessness.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Are we consenting to equality?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Tony Lobl

Recognizing that racism is not caused by, supported by, or known to God is a powerful foundation for progress toward ending injustice.

Are we consenting to equality?

Sam Cooke’s civil rights anthem, “A Change is Gonna Come,” is a timeless classic. I’m sure I’m not alone in wishing it weren’t so timeless a classic. When the song was released during the civil rights era in the United States, it was a bold statement of the social problems being faced at the time, interlaced with the singer’s heartfelt hope. Why, almost 60 years later, aren’t we joyfully singing, “The change has come and it’s permanent!”

Of course, it’s right to be grateful for the hard-won progress made during and since the civil rights era. But the change Mr. Cooke was hoping for clearly hasn’t been fully realized; many obstacles to racial equality remain.

Empathy is a good starting point, but it can’t be the endpoint of our caring for one another. We need to act in ways that make a difference. That includes identifying and consenting to practical steps we need to take – and then taking them. It also demands that we watch what perception of ourselves and our neighbors we are holding in thought, because there’s more to each of us than is detected on the surface.

We each have a God-given identity that is spiritual, made in God’s, Spirit’s, likeness. This is what Jesus proved in his healings recorded in the Scriptures. This spiritual identity isn’t just one aspect of a selfhood that also includes a material form and temporal history, but is actually the whole of what we each truly are as God’s cherished offspring.

When we understand that this is our true existence and recognize that the source of everyone’s spiritual identity is the one Father-Mother God, we see that our coexistence with one another is a fully formed spiritual equality that was, is, and always will be unshakable. This is how divine Love, God, knows and cherishes us all – as a harmonious, spiritual family, all equally endowed and loved by God.

It is the very truth of this underlying spiritual equality that urges tangible change. And one way we can each play a part in forwarding this goal is by asking ourselves, “What expectations am I consenting to? Am I resigned to the seeming intransigence of entrenched attitudes? Or am I accepting that in the light of an understanding of God’s power to change lives, even long-held prejudices can lose their seeming obstinacy?”

The source of that obstinacy is pinpointed in the Bible as “the carnal mind.” This carnal, or mortal, mind is a supposed opposite to the divine Mind or God, and a seeming influence over us that we really do not want to consent to. This material mentality is the underlying foe of progress. It claims to operate in all our thoughts – whether as racism, selfishness, apathy, or a resignation to evil’s appearance of being immovable. But none of these mental outlooks constitute our true nature as the expression of infinite Mind, God.

To contribute to genuine progress, then, it’s not enough to simply acknowledge God’s goodness and our spiritual nature as children of God, although that’s certainly a good starting point for prayer. We need to consent to the actual truth of these all-embracing spiritual ideas, and therefore become conscious of the untruth of opposite mental states that have fueled the history of racism and that prop up its perpetuation.

People in all walks of life have experienced the power of spiritually understanding what is and isn’t true about everyone’s relationship to God. Rereading several such accounts recently inspired me to consider how we can do a better job of consenting to God’s authority.

For instance, if we read such accounts, do we accept that it’s natural for a prayerful, spiritual perception of ourselves and others to forestall or reverse experiences of racism? When a Black friend shared his confidence in relying on the practicality of God’s love in this regard, I realized that I was harboring doubts that God’s love would be sufficient in such circumstances. I wrestled with this lack of faith that I had in God’s goodness until I grasped the spiritual idea that Mind is all-powerful, and that therefore mortal mind isn’t the power it seems to be.

It takes commitment and consistency, but whenever our thoughts yield to divine Truth, it does more than bring a personal sense of peace. It also acts like a light shining into collective human consciousness, supporting the thought that is reaching for a higher and more dependable means of safety for all.

To consistently give prayerful consent to the divine reality that overrules mortal mind’s claims is to follow in the footsteps of Jesus and stand for all humanity’s right to freedom, fulfillment, and equity. In this way, people of all races and cultures can play a powerful part in helping transform Sam Cooke’s “Change is Gonna Come” from an anthem of hope to a prophecy come true.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Aug. 17, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Burning some time

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Two reminders before you start your weekend:

First, Monday is Martin Luther King Jr. Day, a federal holiday in the United States. We’ll send a special treat to you that day, but The Christian Science Monitor Daily will return on Tuesday.

Also, please check out the politics wrap-up and offer your feedback. We’re eager to hear your thoughts. Please send comments to editor@csmonitor.com.