- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Border talks on the rocks? Why Congress hasn’t found a fix.

- Today’s news briefs

- Donald Trump, the Supreme Court, and the 14th Amendment

- Swedish town pays a price for its mining success

- Can China and US cooperate to calm a bellicose Kim Jong Un?

- Poor Paris suburbs count on Olympic promise

- How a tiny town in Namibia saved its beloved rhinos

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The incredible sinking Swedish town

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Imagine if a mining company dug so deep that a town began to sink. And then imagine if the government’s solution was ... to move the city.

That’s Erika Page’s story today. She writes of pockets of frustration in Kiruna, Sweden, but mostly there has been an acceptance that this is for a greater good. I see something similar here in Germany – a deference to authority that is foreign to my American sensibilities. But it’s a reminder. There’s no one right way to solve problems. We can all learn from different perspectives – even when the ground is caving in.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

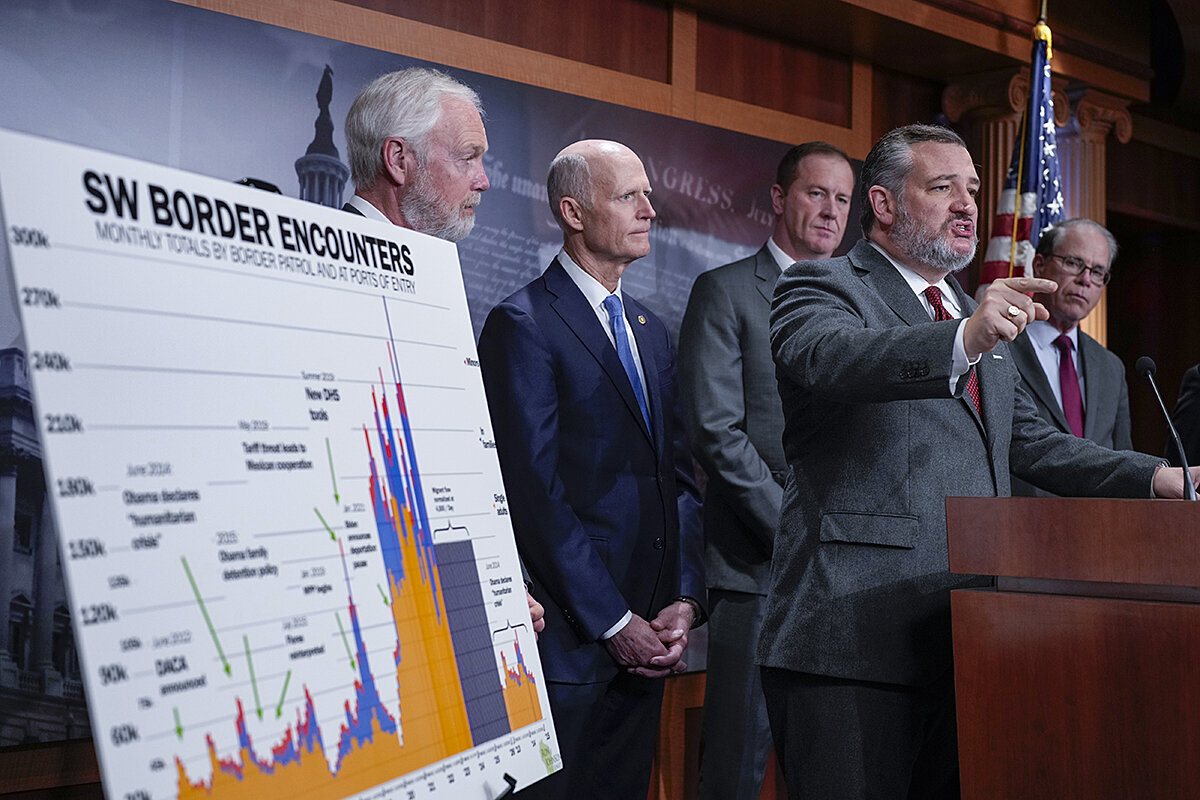

Border talks on the rocks? Why Congress hasn’t found a fix.

While immigration compromise has long eluded lawmakers, a number of factors recently aligned to make a border security deal seem possible. But opposition from former President Donald Trump may halt the momentum.

-

Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

Former President Donald Trump has long fashioned himself as the ultimate dealmaker. But as his presidential campaign gains momentum, he may be the main force threatening a bipartisan Senate deal on one of his pet issues: border security.

Just two days ago, GOP Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said there was “a unique opportunity” for Republicans to win Democratic concessions on enhanced border security measures in exchange for aid to Ukraine and Israel. But after Mr. Trump’s 11-point win in the New Hampshire primary yesterday, Mr. McConnell changed his tune.

“We’re in a quandary,” he reportedly told GOP colleagues in a closed-door meeting, explaining that Mr. Trump wants to use the issue to pummel his likely election opponent, President Joe Biden.

Immigration has been a tough nut for Congress to crack over the years. But many saw this as the best shot in more than a decade, with record numbers of illegal crossings, and Democratic mayors from Chicago to New York pressuring the Biden administration to take action.

There’s still a chance the Senate could broker a deal. But even then, it would then need support from the House of Representatives, where GOP Speaker Mike Johnson has also come under increasing pressure from Mr. Trump not to compromise.

Border talks on the rocks? Why Congress hasn’t found a fix.

Former President Donald Trump has long fashioned himself as the ultimate deal-maker. But as his presidential campaign gains momentum, he may be the main force threatening a bipartisan Senate deal on one of his pet issues: border security.

Just two days ago, GOP Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said there was “a unique opportunity” for Republicans to win Democratic concessions on enhanced border security measures in exchange for aid to Ukraine and Israel. Now was the “ideal time,” he said. But yesterday, after Mr. Trump’s 11-point win in the New Hampshire GOP primary made him the overwhelming favorite to secure the 2024 GOP nomination, Mr. McConnell changed his tune.

“We’re in a quandary,” he reportedly told GOP colleagues in a closed-door meeting, explaining that Mr. Trump wants to use the issue to pummel his likely election opponent, President Joe Biden, where he’s weakest. Indeed, according to a Jan. 22 Harvard/Harris poll, voters ranked immigration as the No. 1 issue facing the nation – and Mr. Biden’s handling of it as the most disappointing aspect of his presidency.

Immigration has been a tough nut for Congress to crack over the years, given the complexity of interlinked challenges to be solved and the difficulty of reaching bipartisan agreement on all of them. But this was seen by many as the best shot in more than a decade, with buy-in from Democratic and Republican leadership in the Senate. A number of factors have heightened the sense of urgency of late: the record numbers of illegal crossings and growing concerns on the right about terrorists entering the country; Democratic mayors from Chicago to New York publicly pressuring the Biden administration to take action; and the border talks being linked to aid for Ukraine and Israel, key priorities for Mr. Biden, as well as some Republicans like Mr. McConnell.

There’s still a chance the Senate could broker a deal. But even then, it would need support from the House, where GOP Speaker Mike Johnson has come under increasing pressure from Mr. Trump not to compromise. This, despite two-thirds of voters supporting stepped-up border security policies, according to the Harvard/Harris poll.

What’s the scope of Senate talks?

This round of talks has focused nearly exclusively on border security and enforcement mechanisms rather than the more ambitious goals of reforming the asylum system or widening channels for legal immigration.

That’s due in part to a spike in illegal immigration. Since Mr. Biden took office in 2021, Customs and Border Protection has had about three times as many encounters with migrants trying to enter the United States illegally as during former President Trump’s tenure, with daily crossings as high as 10,000.

In October, following Hamas’ incursion into Israel, killing more than 1,400, Mr. Biden proposed a $106 billion national security package to bolster the sovereignty of allies under threat, including Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan. He also included $13.6 billion for enhanced U.S. border security to sweeten the deal for Republicans, who have been more skeptical about supporting Ukraine.

In the wake of the Hamas raid, which caught Israel off guard, Republicans have raised concerns that terrorists could do the same in the U.S. More than 310 individuals on the U.S. terrorist watchlist have been arrested trying to cross the southwest border illegally since 2021, compared with 11 during Mr. Trump’s tenure, according to Customs and Border Protection statistics.

Some Republicans say it’s not just more money but a shift in border policy and enforcement that is needed. A key sticking point in the Senate negotiations has been whether to curtail humanitarian parole, which has traditionally been applied fairly narrowly. Under the Biden administration, more than 1 million migrants have entered the country via parole, according to internal government statistics obtained by CBS News.

How does it compare with previous efforts?

Up until now, major congressional efforts to address immigration have sought to enact comprehensive reform, which would include enhanced border security as well as changes to an overburdened system. But a fix has proved elusive.

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed an amnesty law that was supposed to “wipe the slate clean,” legalizing millions already in the country and in theory discouraging others through stepped-up employer restrictions on hiring. But that failed to stop the flow of migrants, or the demand for immigrant labor.

The Immigration Act of 1990 expanded legal immigration but largely focused on higher-skilled workers. No significant immigration legislation has been passed since then. The last major effort was in 2013, when a “Gang of Eight” senators worked out a bipartisan comprehensive immigration reform bill in the Senate, only to have GOP House Speaker John Boehner refuse to bring it to a vote.

What has been different about these latest talks is that border policy is being negotiated on its own, separately from any larger immigration reform. There doesn’t appear to be any real effort right now to address the labor demand, employer enforcement, or the legal limbo of unauthorized immigrants and those brought over as children, known as the “Dreamers.”

“We’re a nation of immigrants; we’re a nation of laws,” says Doris Meissner, former commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service during the Clinton administration and now a senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute. “Efforts in the past have always been trying to kind of thread the needle of those themes. And that’s gone now.”

Why is immigration so hard to address?

While it makes sense in principle to link the various policy questions related to border security and immigration, politically it’s rarely worked. “There are too many ornaments on the Christmas tree for the Christmas tree to stand,” says Ms. Meissner.

Plus, each side has benefited politically from blaming the other. Democrats say they’re in favor of border security, but that it needs to be paired with reforming the entire immigration system. They blame the current crisis at the border on Republicans rejecting previous deals.

“We need to have an honest conversation about how to get real immigration reform in this country without Republicans torpedoing it at the last minute as they have multiple times in the recent past,” says Democratic Rep. Seth Moulton of Massachusetts, a Marine who served in Iraq. “They’re just going to continue using this as a political football at the expense of America’s national security.”

Meanwhile, Republicans accuse Democrats of tolerating a more open border in hopes of increasing the party’s base, since minorities have tended to disproportionately support the Democratic Party. The GOP also says that writing new laws is pointless if the Biden administration won’t enforce them.

“We have a crisis because they refused to enforce our existing laws,” says GOP Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida, the son of Cuban immigrants. “And I don’t personally trust [Mr. Biden] to enforce whatever they agree to in a new deal.”

Negotiating a deal has become harder since the 1980s and 1990s, when the parties were much closer on the issue, says Theresa Cardinal Brown, a former adviser with Customs and Border Protection who is now a senior fellow with the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington. Still, she adds, most Americans hold moderate views on immigration. A July 2023 Gallup poll found that 68% of Americans see immigration as a good thing, while an NBC poll last fall showed that 74% support more funding for border security.

“They believe that legal immigration can be good for the country, but they want to see the border secure, too – these are not opposite things in their mind,” she says.

Editor’s note: A description of the rate of illegal immigration has been updated for greater clarity.

Today’s news briefs

• Alabama execution: Kenneth Eugene Smith is scheduled to be executed by nitrogen gas Jan. 25. The state claims this never-before-used execution method will be humane, but critics call it cruel and experimental.

• Ohio transgender bill: The Ohio Senate votes to override Gov. Mike DeWine’s veto of legislation banning gender-affirming care for minors.

• Former Trump adviser sentenced: Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s trade adviser Peter Navarro is sentenced to four months in prison for contempt of Congress.

• French farmers block roads: Farmers are blocking highways across France and dumping crates of foreign-grown vegetables as they pressure the government to protect them from cheap imports, rising costs, and environmental policies.

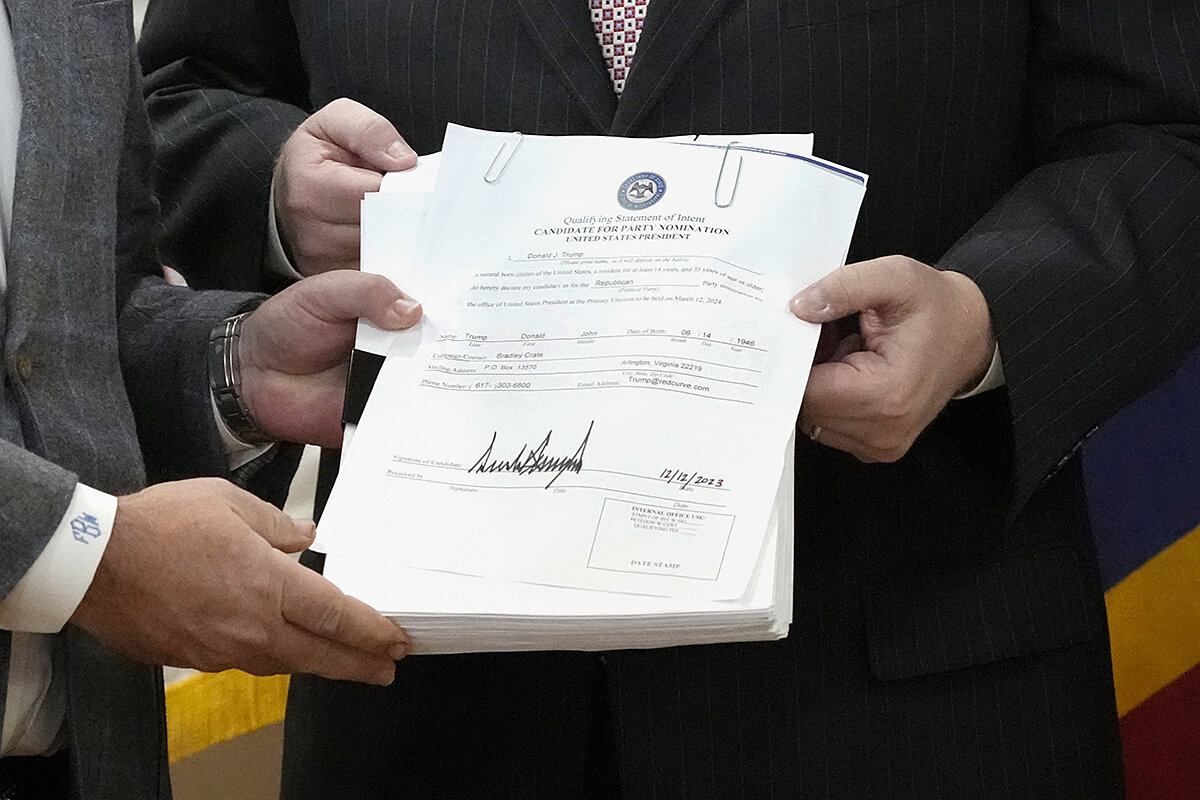

Donald Trump, the Supreme Court, and the 14th Amendment

The U.S. Supreme Court will make a historic ruling this year on whether the Constitution disqualifies Donald Trump from running for president. Ahead of the oral argument next month, the Monitor is previewing the most important questions in the unprecedented case. To read the first installment, click here.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Next month the Supreme Court of the United States will have to decide a seemingly straightforward but monumental question: Is the presidency included in a constitutional provision barring insurrectionists from federal office?

The case, Trump v. Anderson, challenges a ruling from the Colorado Supreme Court that former President Donald Trump – the current front-runner for the 2024 Republican nomination – is disqualified by Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. That provision, enacted after the Civil War, bars anyone who “engaged in insurrection” from holding public office.

But that ruling overturned the decision of a trial judge in Denver. Both the trial judge and the state Supreme Court agreed that Mr. Trump “engaged in insurrection” in the days leading up to and during the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol. But the trial judge determined that Section 3 doesn’t apply to Mr. Trump, since Section 3 doesn’t explicitly mention the president.

The question is one of several complex and rarely litigated issues that the U.S. Supreme Court will be asked to resolve in the case. The decision the justices ultimately reach will be among the most important the court has ever made.

Donald Trump, the Supreme Court, and the 14th Amendment

Next month the Supreme Court of the United States will have to decide a seemingly straightforward but monumental question: Is the presidency included in a constitutional provision barring insurrectionists from federal office?

The case, Trump v. Anderson, challenges a ruling from the Colorado Supreme Court that former President Donald Trump – the current front-runner for the 2024 Republican nomination – is disqualified by Section 3 of the 14th Amendment. That provision, enacted after the Civil War, bars anyone who “engaged in insurrection” from holding public office.

But that ruling overturned the decision of a trial judge in Denver. Both the trial judge and the state Supreme Court agreed that Mr. Trump “engaged in insurrection” in the days leading up to and during the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol. But the trial judge determined that Section 3 doesn’t apply to Mr. Trump, since Section 3 doesn’t explicitly mention the president.

That question is one of several complex and rarely litigated issues the U.S. Supreme Court will be asked to resolve in the case. The decision the justices ultimately reach will be among the most important the court has ever made.

In the abstract, the question might seem absurd. How could a constitutional provision drafted with the goal of keeping ex-Confederates from gaining power in the federal government not include the most powerful office in that government? For a high court in which originalism – the judicial philosophy that the Constitution should be interpreted in line with the framers’ thinking – holds significant sway, this analysis could be central to how it decides the case.

Yet the question is a compelling one, because the presidency is never mentioned in the provision. Instead, the clause specifies “a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President,” as well as “any office, civil or military, under the United States,” as the positions insurrectionists are barred from holding.

What does “office” cover?

For those who believe Section 3 doesn’t cover the presidency, that exclusion speaks for itself. Also, they say, there isn’t enough historical evidence to conclude that the presidency is covered by the phrase “office ... under the United States.” Those on the other side argue the exact opposite. The office of the president isn’t specifically mentioned because it didn’t need to be, they claim, and there is ample evidence that lawmakers and the public at the time thought it was covered by the broad “any office” phrase.

Mark Graber, a professor at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law who believes Section 3 does cover Mr. Trump, describes it as “the George Washington five-finger problem.” No one ever wrote that America’s first president had five fingers on his right hand, so how do we know he did? The likely answer: It was so unremarkable, it passed without comment.

Instead, those on this side of the debate argue that the framers of Section 3 clarified only what they thought needed clarification. There was a lot of thought at the time that senators and representatives held a “seat” instead of an “office,” according to Gerard Magliocca, a professor at the Indiana University McKinney School of Law. And given that they only serve a temporary function every four years, do electors hold an “office”?

When Congress began drawing up the 14th Amendment in 1866, an early draft of Section 3 that specifically included the president was never adopted. During Senate debates of the amendment, there was only one mention of the presidency, when Sen. Reverdy Johnson commented that he did “not see” the presidency or vice presidency. “Why did you omit to exclude them?” he asked. At that point Sen. Lott Morrill jumped in with, “Let me call the Senator’s attention to the words ‘or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States.’”

Beyond that, some scholars point to newspaper coverage around the country in ensuing years indicating that, per Section 3, Confederate leaders would be eligible for the presidency only if Congress granted them amnesty. President Andrew Johnson in proclamations also referred to the president as an “officer of the United States.”

“What reason would [the framers] have for saying, ‘You can’t be a federal officer, but you can be president of the United States?’” asks Dr. Graber.

“The Supreme Court doesn’t want to be laughed at,” he adds. “This [argument] doesn’t pass the laugh test.”

What does Section 3 say?

Critics of this argument believe they have more authoritative historical evidence: other provisions of the Constitution. The impeachment, appointments, and commissions clauses, among others, specify that the president is separate from “officers of the United States.”

A 1799 ruling by the Senate and an 1833 treatise on the Constitution from Justice Joseph Story reinforce that interpretation. The discussion of Section 3 in Congress and around the country during its ratification is too vague to conclude otherwise, they claim.

“Frankly, a single debate in Congress isn’t enough to dictate original meaning,” says Josh Blackman, a professor at the South Texas College of Law Houston, who argues that Section 3 doesn’t cover the presidency.

“Instead of speculating on what the framers intended, we should focus on what the words they chose are,” he adds.

Two months ago, federal district court Judge Sarah Wallace reached the same conclusion. While “there are persuasive arguments on both sides,” she wrote, “the court ... is unpersuaded that the drafters intended to include the highest office in the Country in the catchall phrase ‘office ... under the United States.’”

The Colorado Supreme Court disagreed. A conclusion that the presidency is “something other than an office ‘under’ the United States is fundamentally at odds with the idea that all government officials, including the President, serve ‘we the people,’” it wrote.

How much weight the U.S. Supreme Court will place on that fact is one of the defining questions of Trump v. Anderson. Scholarly research into that question has grown exponentially in the last two months. The justices and their clerks will be poring through these records and drawing their own conclusions. Given the other, more politically sensitive questions, in the case – such as whether or not Mr. Trump “engaged in insurrection” – this may be an appealing issue for the justices to resolve.

Swedish town pays a price for its mining success

When an organization underwrites the needs of the many, how does it balance that against the needs of the few for whom it is directly responsible? That question is percolating in Kiruna, Sweden.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

As the state-owned Swedish mining company LKAB expands its operations, the Arctic town of Kiruna is sinking into the ground. So it’s relocating 2 miles east.

It’s rare to hear complaints about the move. The most beloved buildings are being painstakingly transported to the new town, which aspires to be one of the most modern and livable in Sweden.

Yet seeds of unease have taken root among residents who say their voices have been drowned out. Some wonder if the company lost sight of the balance between meeting its own needs and doing right by the town it founded.

According to Annica Henelund, what has been missing in her interactions with LKAB is respect. She and her sister calculated a sum they would need to close down their family store. For two years, she says, the mining company pressed them on every Swedish krona, putting them on hold for months at a time and flying in a lawyer from Stockholm. “They threatened us,” says Ms. Henelund.

“The relocation process is challenging both LKAB and the municipality to take into account each other’s interests and goals to find solutions that benefit the town,” says researcher Chelsey Jo Huisman. “It can be frustrating when the municipality and residents are needing and wanting to prioritize other values when so much comes down to an economic logic for LKAB.”

Editor’s note: The story was updated to clarify Dr. Huisman’s explanation of the relationship between LKAB and the town.

Swedish town pays a price for its mining success

Annica Henelund swings open the front door of her fabric shop as she has thousands of times before. Inside, not much has changed in the past 51 years. Piles of bright cloth line tabletops and shelves from floor to ceiling. Most of it will never be sold.

In a few short weeks, the store must be empty and ready for demolition.

Residents of Kiruna have long known this moment would come. As the state-owned iron-ore mining company LKAB expands its operations underground, this Arctic town is sinking into the ground. So it’s relocating. A shiny new city center located 2 miles east was inaugurated last fall.

But Ms. Henelund, who runs the store with her sister, didn’t think it would happen like this. They can’t afford rent and other costs in the new center, so they’re closing down the shop they inherited from their mother and aunt. “Things shouldn’t have gone as bad as they did,” she says about two years of tense negotiations with the mining company. “We are so tiny for them. ... But for us, it’s our lives.”

In Kiruna, it’s rare to hear complaints about the city transformation, as the process is called. The project was an urban planner’s dream – a blank slate for reinventing a city of the future. The most beloved buildings are being painstakingly transported to the new town, which aspires to be one of the most modern and livable in Sweden. Though they may prefer to stay, most locals accept the need to move to allow LKAB to continue mining.

Yet seeds of unease have taken root among residents like Ms. Henelund who say their voices have been drowned out. While the revenue that LKAB produces is vital to Sweden’s welfare state – and thus benefits every Swede – some wonder if the company lost sight of the balance between meeting its own needs and doing right by the town it founded.

“We trust LKAB so very, very much. Definitely too much,” says Gunnar Selberg, who served as mayor of Kiruna from 2021 to 2022. Of the town’s 23,000 residents, around two-thirds depend on the mine for employment. In office, Mr. Selberg pushed the municipality to take a stronger stand in its dealings with the company.

“The relocation process is challenging both LKAB and the municipality to take into account each other’s interests and goals to find solutions that benefit the town,” says Chelsey Jo Huisman, a researcher at the Stockholm School of Economics who wrote her Ph.D. dissertation about Kiruna’s city transformation. “It can be frustrating when the municipality and residents are needing and wanting to prioritize other values when so much comes down to an economic logic for LKAB.”

“Mother” of Kiruna

Historically, the mining company has taken its role as the “mother” of Kiruna seriously. No town existed here before LKAB arrived in this icy landscape in 1900. In the beginning, the mining company provided the town’s library, fire station, school, and hospital, as well as housing for workers. The municipality of Kiruna didn’t form until 1948.

In recent years, Mr. Selberg has found himself having to explain this history to company leadership, who now view LKAB’s role in Kiruna primarily through the lens of profit. Whether due to rising global competition or strict stock agreements with the Swedish government, he says that poses a challenge for residents of Kiruna who are used to trusting LKAB to call the shots.

According to Ms. Henelund, what has been missing in her interactions with LKAB is respect. She and her sister calculated a sum they would need to close down the family store. For two years, she says the mining company pressed them on every Swedish krona, putting them on hold for months at a time and flying in a lawyer from Stockholm. “They threatened us,” says Ms. Henelund, tearing up. LKAB did not respond to requests for comment.

“This is something that is a negotiation between LKAB and the private individuals,” says Nina Eliasson, head of planning for the city. As she sees it, most of the 6,000 residents who need to move – close to a third of the population – are satisfied with the process. Businesses were offered space in new shopping centers, and homeowners were given 125% of the market value of their homes.

“You can’t argue with LKAB”

One Sunday evening, a crowd spills out of the Aurora conference center in the new city center, coats hugged tight as wind whips around the town hall. The movie theater sold out for “The Abyss,” a 2023 thriller that imagines the collapse of Kiruna into the ground.

Birgitta Skagerlind isn’t fazed by the dramatization of her town’s plight. Yet she isn’t convinced by the real-life solution. She says she didn’t receive the full sum she was promised for the apartment she owned in the old town – and wasn’t able to afford one of the new apartments. Instead she’s renting.

“You can protest, but about what?” says Ms. Skagerlind, who works at the local hospital. “You can’t argue with LKAB.”

That’s a common refrain around here: Don’t bite the hand that feeds you.

It’s a hand that also feeds Sweden’s government coffers. The deposits under Kiruna are Europe’s richest source of iron ore, 80% of which is produced by LKAB. Its two mines in Kiruna and the nearby city of Gällivare brought in 21 billion kronor ($2 billion) in profit in 2022 – over a third was distributed as dividends to the government, helping to underwrite the country’s social programs.

Meanwhile, the municipality is falling deeper into debt as costs for the city transformation rise. While LKAB foots a portion of the bill, municipal debt reached 2.2 billion kronor ($210 million) in 2022.

Timo Vilgats, a high school teacher, wishes he could have played a more active role in the design of the new school, which opened last fall. But the bigger problem, he says, is that the politicians are “completely united” with the mine. “It means the people have no voice,” he says.

He’s seen other ways of doing things. His eldest daughter works for a mine in Gällivare that similarly forced her family to move to a new area. He says she and her husband felt their needs were listened to and were amazed by how generous the mining company there was in allocating them new space.

In the frenzy of the transformation in Kiruna, Mr. Vilgats feels the human side of things has gotten lost. “I think everyone, especially those with power,” he says, “needs to be more humble, and try to understand.”

Editor’s note: The story was updated to clarify Dr. Huisman’s explanation of the relationship between LKAB and the town.

Patterns

Can China and US cooperate to calm a bellicose Kim Jong Un?

North Korean leader Kim Jong Un is stepping up his nuclear and missile tests, and his bellicose rhetoric. Could this be an opportunity for Beijing and Washington to work together on a common interest?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

As if wars in Ukraine and Gaza were not enough, a new foreign trouble-spot is now preoccupying Washington: the rogue nuclear state of North Korea.

A series of recent bellicose signals from dictator Kim Jong Un has left policymakers pondering a question that has long seemed unthinkable: Behind the bluster, might Mr. Kim actually be gearing up to use his nuclear weapons?

And another question: How ready will China be to help stay his hand?

International concern over Mr. Kim’s nuclear program is nothing new, although the pace and sophistication of North Korea’s military tests and missile firings are on the rise.

Even more worrying to North Korea policy experts, however, are signs of a major political and diplomatic shift by Mr. Kim: He has strengthened ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

And he used a recent speech to insist that North Korea’s Constitution be amended to define South Korea as Pyongyang’s most hostile foreign adversary and to provide for “completely occupying, subjugating, and reclaiming” South Korea in the event of war.

That would not be in China’s interests at all. As U.S.-China relations begin to thaw slightly in the wake of President Joe Biden’s meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping last year, the stage seems set for a test of their ability to work together.

Can China and US cooperate to calm a bellicose Kim Jong Un?

Nikki Haley, in her defiant primary-night pledge to keep challenging Donald Trump despite her loss in New Hampshire, warned of a “world on fire – with a war in Europe and the Middle East, and a huge and growing threat from China.”

But another foreign trouble spot is now preoccupying Washington: the rogue nuclear state of North Korea.

A series of recent bellicose signals from North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un has left policymakers pondering a question that has long seemed unthinkable: Behind the bluster, might Mr. Kim actually be gearing up to use his nuclear weapons?

The United States and its Asian allies have been betting on military deterrence to stay his hand. Yet diplomatic and political pressure could prove equally important.

And that’s confronting the West with an uncomfortable truth of 21st-century geopolitics: The nation best positioned to exert a restraining hand on Mr. Kim is the one that Ms. Haley termed a growing threat.

It is China.

The immediate challenge, however, is to decipher what’s going on in North Korea, a task that has taken on increasing urgency in recent days.

International concern over Mr. Kim’s nuclear program is nothing new, although the pace and sophistication of North Korea’s military tests and missile firings are on the rise.

Even more worrying to North Korea policy experts, however, are signs of a major political and diplomatic shift by Mr. Kim.

He has strengthened ties with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The two leaders met last September, paving the way for what appears to be an expanding military partnership. North Korea has reportedly sent Mr. Putin around a million artillery shells to use against Ukraine, and Mr. Kim is expecting Russian satellite and guidance technology to bolster his weapons development program.

Last week, Mr. Putin accepted an invitation to visit North Korea “at an early date.”

Kim’s dramatic shift

The political shift inside North Korea has been even more dramatic.

Late last year, Mr. Kim used a speech to his rubber-stamp legislature to abandon a core doctrine dating back to his grandfather’s rule during the Korean War of 1950-1953: the goal of eventually reunifying the Korean Peninsula.

He now wants North Korea’s Constitution to be amended to define South Korea as Pyongyang’s most hostile foreign adversary and to provide for “completely occupying, subjugating, and reclaiming” South Korea in the event of war.

That war would be inevitable, he warned in his December speech, if Seoul “violates even one thousandth of a millimeter” of their long-disputed maritime border.

In a symbolic exclamation point this week, the North Koreans appear to have demolished a monument symbolizing reconciliation with the South, the Arch of Reunification, erected in 2000 on the southern edge of the capital during an earlier period of détente.

None of this necessarily means Mr. Kim intends to go to war. He has in the past used warlike rhetoric and weapons tests to attract international attention, not least from the U.S., in his bid to normalize ties and end sanctions.

He may even be positioning himself for the possible return of Mr. Trump, with whom he embarked on a failed effort to trade normalization for eventual denuclearization.

But two of America’s most respected Korea experts – policy and intelligence analyst Robert Carlin and nuclear specialist Siegfried Hecker – weighed in this month to argue that today’s circumstances are very different.

On the 38 North website, which specializes in North Korean affairs, they said Mr. Kim had been stung by the failure of his summits with Mr. Trump and had jettisoned the idea of rapprochement with America.

Calling the situation more dangerous than at any time since the Korean War, they wrote “we believe that, like his grandfather in 1950, Kim Jong Un has made a strategic decision to go to war.”

So far, the Biden administration seems worried but not alarmed. “We’re watching very, very closely,” U.S. National Security Council spokesman John Kirby told reporters this week. But he added, “we remain confident that the defensive posture we’re maintaining on the peninsula is appropriate to the risk.”

China’s leverage

Still, U.S. officials are aware of the 38 North article, amplified across the world’s news media.

Which is why America’s main Asian rival – China – may loom large in efforts to prepare for the possibility that Mr. Carlin and Mr. Hecker are right.

Since the Korean War, Beijing has been North Korea’s closest ally. Chinese leader Xi Jinping isn’t about to abandon that relationship, especially when Mr. Kim has been hedging his diplomatic options by drawing closer to Russia.

But China has leverage: North Korea’s economy would collapse without Chinese support.

It has strategic interests, too. The last thing Beijing wants, as it expands its superpower influence in the region, is a war on its eastern border.

As U.S.-China relations begin to thaw slightly in the wake of President Biden’s meeting with Mr. Xi last year, the stage seems set for a test of their ability to work together.

Mr. Biden has long stressed the need for a managed rivalry, with scope for cooperation on challenges of shared interest. The prime example cited by U.S. officials until now has been climate change.

Now, there could be another: keeping North Korea’s words of war from becoming acts of war.

Poor Paris suburbs count on Olympic promise

This year’s Olympic Games will be held in one of France’s poorest communities. Residents are anxious to believe official promises that “Paris 2024” will leave them a brighter legacy.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

From a new billboard affixed to the wall of a Paris suburb library, kickboxing world champion Mohamed Diaby looks out with a confident smile next to a call to action: “Together, let’s go beyond our limits. ... The 2024 Olympic Games in Seine-Saint-Denis, we’re ready!”

Mr. Diaby, who is Franco-Malian, grew up here. He represents the vibrant diversity of Île-Saint-Denis, one of the poorest communities in the country. He is also proof of the sense of pride and promise that the Olympics can bring to local residents.

Urban planners are building much of the Olympic landscape from scratch. But Paris Olympics officials have made a concerted effort to involve residents in the planning process, and they are promising to leave a lasting legacy that will benefit local communities.

“What will the legacy be of this Olympic Games? What do we do afterwards?” asks Martin Citarella, an urban planner for the regional Olympics and Sports Committee. “The Olympics can’t act like a magic wand. But our hope is that once it’s all over, the flame doesn’t go out.”

Poor Paris suburbs count on Olympic promise

In the town center of Île-Saint-Denis, a new billboard is affixed to the wall of the local library. Kickboxing world champion Mohamed Diaby looks out with a confident smile next to a call to action: “Together, let’s go beyond our limits. ... The 2024 Olympic Games in Seine-Saint-Denis, we’re ready!”

Mr. Diaby, who is Franco-Malian, grew up in this Paris suburb and represents the vibrant diversity of Île-Saint-Denis, one of the poorest communities in the country. He is also proof of the sense of pride and promise that the Olympics can bring to residents here.

The sprawling region of Seine-Saint-Denis – which includes Île-Saint-Denis, just northeast of Paris – will host swimming, gymnastics, and track and field events, and house the 15,000 athletes expected at the Olympic Village.

While urban planners are making use of existing infrastructure, they have had to build much of the Olympic landscape from scratch. Paris Olympics officials say they’re committed to sustainable development and plan to leave a legacy that will benefit local communities.

But such promises have been made before by other Olympic host cities, and here the changes have not been to everyone’s taste. Some residents worry about noise and air pollution, or that any new housing will be too expensive for them.

Still, local authorities have made a concerted effort to involve residents in the planning process. That’s providing hope that – unlike after previous Olympics in Rio de Janeiro and Athens – the new infrastructure will be used once the Games have moved on, and that it will create lasting positive change.

“What will the legacy be of this Olympic Games? What do we do afterwards?” asks Martin Citarella, an urban planner for the regional Olympics and Sports Committee. “The Olympics can’t act like a magic wand. But our hope is that once it’s all over, the flame doesn’t go out.”

Looking forward first

Seine-Saint-Denis is no stranger to transformation. Once Europe’s second-largest industrial hub, the area saw a rapid deindustrialization in the 1970s that turned factories into corporate headquarters, and a power plant into a film studio complex. But it also brought high levels of unemployment among its large working-class population, striking economic inequalities, and crime.

That legacy has created extra challenges for urban planners tasked with preparing the Games: pleasing the Paris Olympics organizing committee while also honoring the area’s history and meeting the community’s needs.

“The Olympics are an amazing event,” says Dominique Perrault, whose architecture firm is leading the design of the Olympic Village. “But for local communities, they are not a response to their needs in and of themselves.”

In the short term, Seine-Saint-Denis must build the Olympic Village – a collection of apartment complexes across three neighboring suburbs – a connecting bridge, and a new aquatics center.

But instead of leading with Olympic demands, urban designers used an atypical approach: They focused first on how Seine-Saint-Denis should look after the Games.

In 2017, local entrepreneurs were asked to come up with ideas. Urban planners met with Seine-Saint-Denis mayors about their aspirations for the Olympic Village, while mayors held citizen forums and met with nonprofits and parent groups to maximize public participation. The Olympic Village is now an expanded version of a project for an eco-village that was already underway.

“We had envisioned this environmentally friendly space before Paris was even selected to host the Olympics,” says Mohamed Gnabaly, the mayor of Île-Saint-Denis. “The Olympics have just accelerated that transformation.”

In 2025, the village will be reconfigured into 2,400 housing units – with up to 40% of them set aside as public housing – alongside schools, hotels, and a 5-acre park. The Games have also pushed forward construction of what will become one of the largest metro stations in the region as part of a broader project to extend Ile-de-France’s regional train network by 120 miles.

There is hope that this investment will have knock-on effects, boosting a region bursting with youth and a vibrant startup culture but weighed down by a reputation for crime.

“More people are starting to see Seine-Saint-Denis as a young, hip place to be, where there’s this great urban arts scene,” says Hafida Guebli, a startup founder and advocate for public housing tenants in Saint-Denis. “I see these new buildings being put up and lots of good things coming. But we’ll have to see if [local leaders] keep their promises to us.”

Free tickets – a good start

Not everyone is enthusiastic about the changes. A Seine-Saint-Denis parents’ association has expressed concern about the effects of air pollution on schoolchildren, as construction continues. Others say the Olympic Village renovations don’t include enough green space.

And although the Olympic Village is supposed to provide housing after the Games, some local residents worry that it won’t be affordable. In Île-Saint-Denis, 75% of the population currently lives in state-subsidized homes.

“Who is going to buy [a home] here?” wonders Cécile Gintrac, a Saint-Denis resident who heads up the Vigilance Olympic Games 2024 citizens group. “We’re largely a poor district. I’m not against new people coming in, but this is only going to increase the gap between rich and poor.”

Mr. Gnabaly, the mayor, says he wants to focus on selling to families, ensure diversity, and avoid gentrification. But the Olympics will inevitably change the social and economic dynamics of the area, especially as improvements to the subway system make it easier to get there.

Within the athletic community, though, there is little doubt about the opportunities the Olympics will bring. The region has a serious lack of sports facilities; soon it will have some of the best in the world. And venues like the new aquatics center could become a democratizing force for local residents.

In Île-Saint-Denis, Mayor Gnabaly has taken things a step further. Early on in the process, he organized a deal with Olympics officials to provide each resident with a ticket to an Olympics event.

While a free ticket to the Olympics may not address the concerns about housing or pollution, local leaders hope it will bolster an appreciation of how positively the Games might change Seine-Saint-Denis, now and in the future.

“Right now, there’s lots of construction and noise. It’s been difficult for people,” says Mr. Gnabaly. “But later on, all of this will be for them.”

Difference-maker

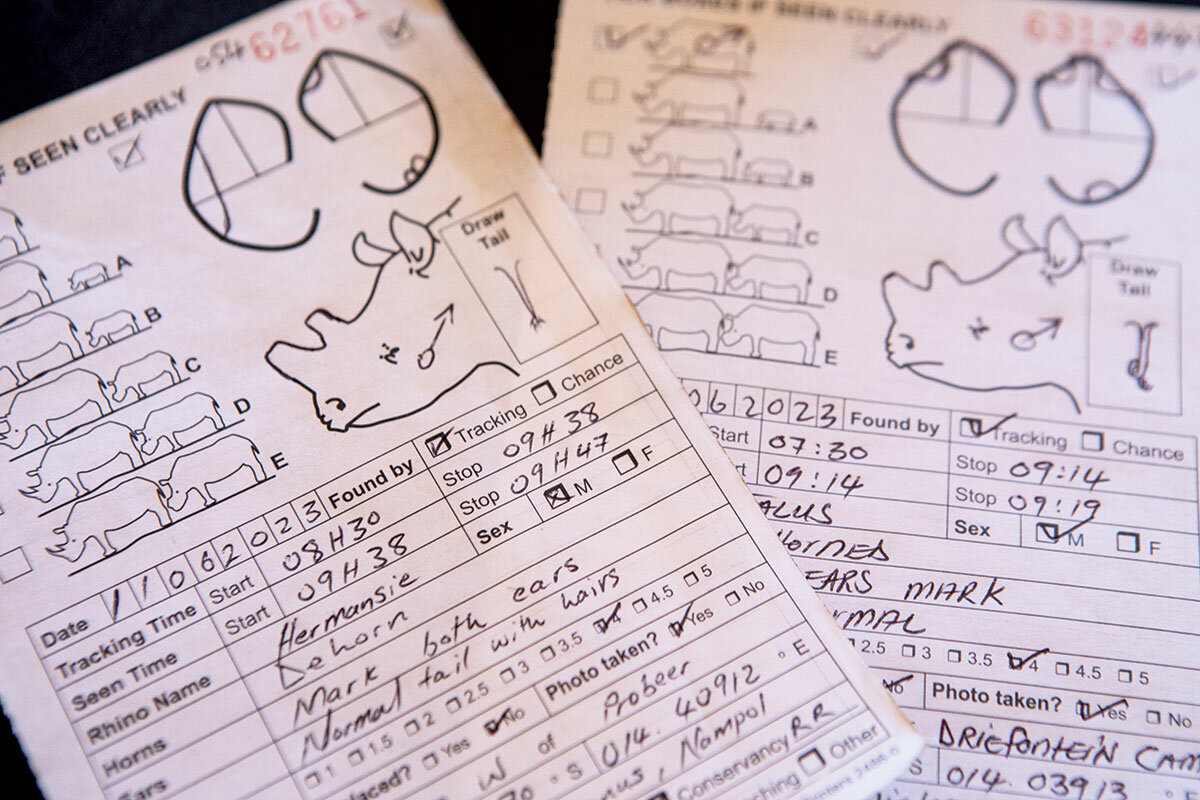

How a tiny town in Namibia saved its beloved rhinos

As poaching soars across Namibia, one community hasn’t lost a rhino to poachers in three years. How’d they do it? By working with the community.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

Every day and every night, rhino trackers trek into the desert plains of northwest Namibia in search of a rare, desert-adapted subspecies of black rhinoceros. They aren’t alone.

Last year, poachers killed 87 rhinos in Namibia. But this community hasn’t logged a rhino poaching in three years. That’s because, under Namibia’s community conservation model, safeguarding the animals is more lucrative than selling them on the illegal market.

At Palmwag Lodge, tourists from around the world laze around two pools after spending around $150 for a half-day rhino-trekking tour. “The rhinos attract the white people, and that gives us jobs,” says one server and mother of three who has found steady work at the lodge for the past seven years. “We all care about rhino conservation here.”

The model also appears to be working for the rhinos.

When Save the Rhino Trust was established in 1982, only 50 black rhinos roamed this area. Forty years later, Namibia hosts almost 35% of the world’s remaining black rhino population. As to the exact number? “That’s a state secret,” says the organization’s CEO.

How a tiny town in Namibia saved its beloved rhinos

The rhino trackers trek a mile into the open desert plains of northwest Namibia. They stop 300 feet from a desert-adapted black rhinoceros grazing on the rocky hillside.

Rhinos have poor eyesight, so the windy day works in the trackers’ favor, making it harder for the animals to locate them by sound or smell. Sebulon Hoeb, the principal field officer of Save the Rhino Trust Namibia, wants to get closer, but his partner today, Ebson Mbunguha, has his binoculars trained at the distance. He tells the group to back away. He has identified this rhino: Matty 2. She is 4 years old, which means her mother probably has a new baby and could appear on the open plain at any moment. There are no trees to climb if the crew is suddenly surrounded by creatures that can weigh as much as 3,000 pounds.

Plus, they’ve identified her. Their job is now done.

Every day and every night, trackers from Save the Rhino Trust, alongside rangers from the local community, patrol 25,000 square kilometers (just under 10,000 square miles) in Namibia’s northwest, the only place in the world where this desert-adapted subspecies of the black rhino is still truly wild. Even if these animals are spotted from a distance, the trackers know them so well that they can identify them from their behaviors, roaming patterns, and physical features like birthmarks. It’s all documented on small pieces of paper that pile up back at Save the Rhino Trust headquarters in the pinprick of a town, Palmwag.

The trackers are not just building a living database of conservation or scientific study; patrolling is the best tool they have against rhino poaching. And the work is paying off.

Rhino conservationists discourage publishing the price of horns on the black market, in order to deter criminal activity, but rhino horns are in high demand, especially in China and Vietnam. After years of successfully clamping down, Namibia saw rhino poaching increase by 93% last year over the year before, according to the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism. But here the community hasn’t logged a rhino poaching in three years. That’s because, within the structures of Namibia’s community conservation model, safeguarding the animals is more lucrative than selling them on the illegal market. It’s an ultimate win-win.

“Most of us understand that the rhino pays us,” Mr. Hoeb explains plainly.

The desert-adapted rhino, one of the oldest mammals on Earth, has roamed this arid, red-earth region that glows at sunrise and sundown for millennia. Its presence is depicted in the ancient cave art found in nearby Twyfelfontein, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

But in the 20th century, European hunting all but eradicated its numbers. Between 1960 and 1995, black rhino numbers dropped by 98% to fewer than 2,500.

Save the Rhino Trust was established in 1982, when only 50 black rhinos roamed this area. Forty years later, Namibia hosts almost 35% of the world’s remaining black rhino population, although the exact number is tightly guarded. “That’s a state secret,” says Simson Uri-Khob, the CEO who has dedicated his career to saving the rhino.

An environmental pioneer

When Namibia gained its independence in 1990, it became the first country in Africa to protect the environment in its constitution. It also created community conservancies – lands with defined borders and governances outside the national park structure, where the communities themselves benefit from the resources, including animals, on their homelands. Today the government counts 86 communal conservancies covering more than 20% of the country’s territory. Many of these conservancies thrive by running lodges that draw tourists to see wildlife, in turn fueling local economies.

Steve Galloway, chairman of the Community Conservation Fund of Namibia, says community conservation represents the best of both worlds. It puts large tracts of land under environmental protection – but not at the expense of people. “You bring in tourists, and you grow vegetables for those tourists and curios for those tourists. You do hiking trails, and you create a whole ecosystem,” he says.

In other words, here in Palmwag, everyone is vested in the sighting of Matty 2.

Waatara Karutjaiva, a server at Palmwag Lodge, has found steady work here for seven years. At the lodge, tourists from around the world laze around two pools looking out at flat-topped mountains and makalani palms, after spending around $150 for a half-day rhino-trekking tour. “The rhinos attract the white people, and that gives us jobs,” says the mother of three, whose father and brother also work at Save the Rhino Trust. “We all care about rhino conservation here.”

But they remain on guard. Prolonged drought and encroachment from mining are disrupting wildlife populations. And even though overall rhino numbers are up, so is the threat of poaching. Last year 87 were killed, with the problem concentrated in Etosha National Park. Wilburd Andreas Rasta has worked as a game guide for 16 years and has never seen pressure like this. “As we are speaking, they are poaching,” he says.

In Etosha, it is the military and police that patrol the area; to address the increased threats, they’ve recently expanded patrols to include horseback personnel and implemented more high-tech surveillance. But for Save the Rhino Trust, it’s the community that forms the foundation of surveillance to protect its rhinos. “Everybody knows me. Everybody has got my cellphone number,” says Mr. Uri-Khob. “It’s a very busy cellphone, this one.”

“Community conservancies in Namibia are groundbreaking and incredibly powerful and positive, and really leading the way in bringing people who live with wildlife to have a meaningful participation in the way that wildlife is managed,” says Jo Shaw, CEO of the United Kingdom’s Save the Rhino International (a separate organization in Namibia). “It’s just such an important and positive model for Africa ... creating that positive link between people and wildlife that is so often missing elsewhere.”

Dr. Shaw argues that rhinos are important not just unto themselves, but also because they are a keystone species. Their health means that other species are also safe and that the ecosystems that they need to survive are intact.

A day in the life

The rhino rangers start the day under a starry southern sky in the Namibian desert, driving through places called “Rhino Valley” or “Poacher’s Camp.” Mr. Mbunguha gets out of the car to identify footprints in the dusty earth. He quickly determines that they are old. The rangers drive up to a ridge overlooking a canyon dotted with the Damara milk-bush that protrudes from the barren red earth in clusters of green-gray – poisonous to most animals but not to rhinos. From the back of the truck, police officer Naftal Nambambi is scanning the distance to protect against poachers who are a danger to both the animals and the rangers.

It’s no easy job. A 24/7 operation demands that the rangers live in tents for three weeks at a time, doing most of their tracking on foot. They get a bonus for how many kilometers they walk and how many sightings they log. It can be dangerous. “I’ve had to run for my life many times,” says Mr. Hoeb. He and Mr. Uri-Khob, who have worked together for years, once were chased and had to hide under the toxic milk-bush (quickly finding a stream to wash off the toxins when it was safe).

Mr. Uri-Khob, who won the Prince William lifetime achievement award in 2021 in recognition of a career dedicated to conservation, says that this work is not just about the local economy.

When he focused his master’s degree on the reintroduction of the black rhino in its historical range, he asked community members hundreds of questions to gauge their attitudes. He found that the people here are simply attached to a creature that has always roamed this land. “We are proud because the rhinos are here, but they are not everywhere,” he says. “We managed ours from near extinction.”

Everyone has a story about a rhino. Mr. Uri-Khob has one, too.

He recalls a 6-year-old rhinoceros that stood in the middle of the Namibian desert, during one of their workdays. The young bull approached the group of game guards and stared them in the eyes; it then did a little flip with its body to turn itself around, walked back, and then flipped around again to meet their eyes. It was a move they’d never seen before, or since.

Mr. Uri-Khob was charmed by the show, and what seemed like its nonchalance in the face of humans. He named the rhino Don’t Worry, and tracked his movement and growth over 30 years.

When Don’t Worry died, in 2020, it was of natural causes – not at the hands of a poacher.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to restore a few sentences that had been inadvertently omitted on initial publication.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

In Chinese homes, gains in equality

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

When it was first reported last month, a minor new statistic on parenting in China hardly raised a shrug. The number of fathers in Shanghai serving as primary nighttime caregivers for their children rose by 5% since 2018. That starts from a low base. Nationwide, the amount of child care provided by fathers is negligible.

Yet that modest shift in Shanghai may reflect a wider and quieter trend. Contrary to China’s decline in global surveys on gender equality in recent years, a paper published Thursday by two Chinese academics found that, within Chinese households, the reverse is happening. That insight is likely not to go unnoticed by officials in Beijing because its key driver is the target of state control: the internet.

“The use of the Internet significantly shapes women’s perceptions of gender roles, fostering a transition from traditional to egalitarian perspectives,” the study found.

In Chinese homes, gains in equality

When it was first reported last month, a minor new statistic on parenting in China hardly raised a shrug. The China Welfare Institute of Development Research Center found that the number of fathers in Shanghai serving as primary nighttime caregivers for their children rose by 5% since 2018. That starts from a low base. Nationwide, the amount of childcare provided by fathers is negligible.

Yet that modest shift in Shanghai may reflect a wider and quieter trend. Contrary to China’s decline in global surveys on gender equality in recent years, a paper published Thursday by two Chinese academics found that, within Chinese households, the reverse is happening. That insight is likely not to go unnoticed by officials in Beijing because its key driver is the target of state control: the internet.

Women “tend to have relatively lower bargaining power within their households, reflecting the established societal structure in China” with respect to owning property, managing household chores, and caring for children, the authors noted. “The use of the Internet significantly shapes women’s perceptions of gender roles, fostering a transition from traditional to egalitarian perspectives.”

The paper, published in the journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, assessed the role of the internet in building household bargaining power for women. Perhaps surprisingly, it found that the most significant change is taking place in rural areas, where gender roles are more likely to be shaped by long-standing community expectations and access to the internet is more likely to be hampered by poor infrastructure.

Despite such factors, rural women are finding community, job opportunities, new avenues to education, and access to feminist ideas that the government of leader Xi Jinping has sought hard to silence. “This surge in exposure directly correlates with increased participation in family matters,” the authors wrote.

The paper notes a correlation confirmed by experience in other countries – that more blending of masculine and feminine qualities by couples results in a higher degree of happiness, family stability, and social prosperity.

The Chinese leader stresses the need for “cyber sovereignty” and for other countries to respect “each country’s way of internet governance.” Yet Beijing’s stiffening regulations on digital content have not been able to stall a deepening of individual sovereignty among Chinese people, driving equality between women and men.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Combating compassion fatigue

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Karen Neff

In learning that our foundation is divine Love, we find there’s no limit to the kindness and generosity we can share in our communities.

Combating compassion fatigue

A friend told me recently that as she approached a store on New Year’s Day, a young man came out carrying two big bouquets of flowers. He handed her one, saying, “This is for you. Happy New Year!” and kept going. How heartwarming it was to hear of someone expressing such kindness, apparently for the first two people he encountered that day.

A small act like this can do much to help someone overcome discouragement and hopelessness. It certainly did for my friend, who had been going through a difficult time.

In a society where the term “compassion fatigue” has been growing more common, we too can fight against apathy and hopelessness by arming ourselves with deeds of goodness and thoughtfulness. We can take a strong mental stand against selfishness and indifference and find a spiritual basis to combat the evil that seems so overwhelming and prevalent.

Mary Baker Eddy, who discovered the laws of God and named them Christian Science, wrote, “In the battle of life, good is made more industrious and persistent because of the supposed activity of evil. The elbowing of the crowd plants our feet more firmly. In the mental collisions of mortals and the strain of intellectual wrestlings, moral tension is tested, and, if it yields not, grows stronger” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 339).

It is the truth of God’s allness that empowers us not to be bowled over by troubles. God is our Father, and we are His flawless reflection, made in God’s image, in the image of divine Love. As such, our true nature is always peace-loving and non-reactive amidst the push and pressure of any fear and aggression we encounter.

A simple gift of flowers can be a symbol of what the Bible refers to as “the weapons of our warfare,” which “are not carnal, but mighty through God to the pulling down of strong holds” (II Corinthians 10:4). These “weapons” are spiritual qualities such as compassion, tenderness, and goodness that come into play when we express tender, heartfelt kindness to another; take a strong moral stand for right thinking and acting; or courageously refuse to react in fear, anger, or discouragement amidst reports of violence and evil in the world.

Our expression of these spiritual qualities does indeed make us stronger, because they have their source in God, in divine Love. The Bible tells us, “God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him” (I John 4:16). It is man’s unity with God, the oneness that Christ Jesus taught belongs to each of us, that gives us the ability to counteract reports of evil with compassionate deeds of caring. And because each inspired thought and act has its inception in God, divine Love, instead of human will, its capacity to bless is boundless.

It is not human goodness that blesses but God’s benevolence, which we reflect. So we can always take a stronger stand for goodness and gentleness in the world. And every tender, loving act counts! Each one adds a drop of progress and prosperity to the bucket of the world’s thought, reducing fears and positively influencing humanity to collectively rise higher. We may never know how much a gentle touch, a smile, or a word can lift and strengthen another who may be struggling.

In a sermon that was delivered at the start of a new year (see “Pulpit and Press,” p. 4), Mrs. Eddy quoted these lines from a poem by William Cutter:

What if the little rain should say,

"So small a drop as I

Can ne’er refresh a drooping earth,

I’ll tarry in the sky."

Haven’t we all felt this way at one time, wondering what difference our small contribution would make? If our taking a stand for goodness appears small, then we can remember that God is the source of every positive thought and act, so each loving offering comes with all the might of God’s tender love supporting and prospering it. As God’s offspring we have an unlimited capacity to bless our fellow man with deeds of tenderness and caring.

We can each make a commitment to take a more active stand for good in our life and resist being pushed and buffeted by reports of evil. We can plant our feet more firmly and contribute to a campaign of compassion, caring, and unselfish giving. This is a battle we can fight and win through the grace of God, and we will surely see the change it brings to a waiting world.

Viewfinder

Off the rails

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Here’s our final reminder for the online event we’re holding tonight at 7 p.m. Eastern time. We’ll look deeper into our Climate Generation series, examining the lives of the young people leading the search for solutions to climate change. You can find the Facebook Live page here.