- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Can El Salvador embrace democracy – and an authoritarian?

- Today’s news briefs

- In Gaza, humanitarian network in crisis as people’s needs soar

- Crypto was to address a collapse of trust. But can it be trusted?

- Israel’s Netanyahu fights against Hamas, and for his future

- Perks and perils of being married to a photographer

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Introducing our next big project: Rebuilding Trust

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Today, the Monitor begins its next big project, Rebuilding Trust. You won’t see balloons and confetti. The idea isn’t to start with a bang. Rather, our goal for the coming months is to provide stories each week that focus on the crucial role of trust in the world today.

You don’t need to go far to hear about a trust crisis. Trust in our institutions is falling. So is trust in our political opponents. Trust that we can save the planet. Today, Erika Page kicks us off with a look at trust in cryptocurrency.

But trust is the lubricant of world progress. How can we rebuild trust? What emerges is the importance of trustworthiness. To build trust, one must be worthy of trust. Trust is the compass needle that points us toward where we can do better.

Rebuilding Trust will build on our previous values projects, such as The Respect Project and Finding Resilience, as well as our more recent values approach to a wide variety of our stories. News, after all, is not just about a fight over policies. It’s also about the clashing of values we hold dear. Realizing that gives us greater understanding and agency.

The goal is to do what our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, told us to do: “Bless all mankind.” We know the role media plays in how we see the world. By looking at trust in the months ahead, we hope not only to provide more clarity on the issues that really matter, but to give you a more constructive and credibly hopeful way of seeing them.

You can find the project at www.CSMonitor.com/trust. We hope you’ll come back in the coming weeks as the project gains momentum.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Can El Salvador embrace democracy – and an authoritarian?

Salvadorans want democracy. But amid widespread violence that has wracked their nation since the end of civil war, citizens are voting for security over democratic governance.

-

By Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Nelson Rauda Special contributor

Across Latin America, it is Salvadorans who embrace democracy more than almost all of their peers do. Support for democratic governance in El Salvador stands at 73%, higher than in any country in the region except Uruguay.

Yet over the past five years of his presidency, Nayib Bukele has systematically weakened the pillars of democracy that this Central American nation has tried to build since the end of a civil war in 1992 – and his ratings remain sky-high. That’s in large part because he’s ushered in newfound peace in a country riven by brutal gangs, violence, and extortion.

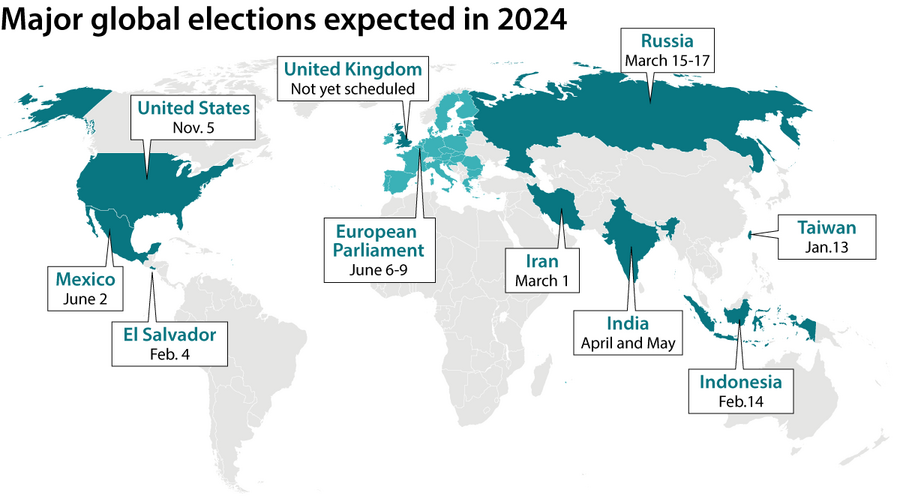

As Salvadorans head to the polls Feb. 4, with all indications that Mr. Bukele will win reelection, these paradoxes are on full display. They show the tensions between governance and security, and, particularly in a young democracy, what a populace is willing to overlook for the sake of living without fear.

“For the majority of people here, democracy is synonymous with elections,” not with independent institutions, says Álvaro Artiga González, a political scientist at El Salvador’s Universidad Centroamericana. Improved security was achieved through a militarized response to criminal gangs. But the plan was “created by a government that won the popular vote,” Dr. Artiga says. “And people are satisfied with that.”

Can El Salvador embrace democracy – and an authoritarian?

Across Latin America, it is Salvadorans who embrace democracy more than almost all of their peers do. Support for democratic governance in El Salvador stands at 73%, higher than in any country in the region except Uruguay.

Yet over the past five years of his presidency, Nayib Bukele has systematically weakened the pillars of democracy that this Central American nation has tried to build since the end of a civil war in 1992 – and his approval remains sky-high. That’s in large part because he has ushered in newfound peace in a country riven by brutal gangs, violence, and extortion.

As Salvadorans head to the polls Feb. 4, with all indications that Mr. Bukele will win reelection, these paradoxes are on full display. They show the tensions between democratic governance and security, and, particularly in a young democracy, what a populace is willing to overlook for the sake of living without fear.

“For the majority of people here, democracy is synonymous with elections,” not with independent institutions, says Álvaro Artiga González, a political scientist at El Salvador’s Universidad Centroamericana.

The authorities improved security by deploying the army against criminal gangs, and resorting to mass arrests and extrajudicial killings. But the plan was “created by a government that won the popular vote. And people are satisfied with that,” says Dr. Artiga.

A balancing act

When Pedro Rojas got a late-night visit from his daughter on New Year’s Eve in his small community east of San Salvador, it surfaced the dueling values in his own life.

His daughter’s holiday visit “was such joy,” he says, “because for so long it was impossible.”

Today “we have security,” says Mr. Rojas, who works at a local private school. “But at what cost?”

Like so many, Mr. Rojas and his neighbors have lived under a reign of terror for most of the past decade, orchestrated by local gangs that successive governments failed to control.

Walking down the main road, bustling with churchgoers and food vendors, on a recent Sunday afternoon, Mr. Rojas ticks off some of the unspoken rules of the very recent past. He couldn’t say hello or acknowledge neighbors, and he wouldn’t dare answer a phone call or text message on the street for fear it could be construed as sharing information with an enemy.

He credits Mr. Bukele with tackling such obstacles to normal life.

In March 2022 the government declared a “state of exception,” which has given sweeping powers to arrest and detain suspected criminals without warrants – or even evidence. More than 75,000 people have been arrested since, and today roughly 2% of the adult population is behind bars.

At the same time, Mr. Bukele has stacked the courts with allies who went on to “reinterpret” the constitution to allow him to run for a second term. And he has gerrymandered to such an extent that the number of municipalities nationwide will shrink this spring from 262 to 44.

Mr. Rojas says he has tried to talk with his middle school students about squaring the government’s democratic credentials with its authoritarian tendencies. He is academic coordinator at the Colegio Cristiano Las Cañas, a humble, one-story concrete building, where he sees his job as “orienting” youth to think critically – not as telling them that democracy is weakening.

“Is it good or bad” that Bukele has concentrated power? he asks. “I don’t know that we’ll truly know until we’re looking in the rearview mirror.”

For Dr. Artiga, looking in the mirror is something El Salvador needs to do sooner rather than later. “We have two clear examples of what [these changes] can mean over time: the case of Venezuela under [Hugo] Chávez, and Nicaragua with Daniel Ortega,” he says.

Today there’s “zero debate, zero analysis, zero discussion” in the Legislative Assembly, which is controlled by Mr. Bukele’s party, says Eduardo Escobar, executive director of Acción Ciudadana, a San Salvador-based nongovernmental organization promoting transparency. But that means that laws pass quickly and the president can effect change efficiently. “People are saying, ‘Democracy wasn’t serving us before, but now it’s delivering!’ And for that they are satisfied, even if it’s against the universal concept” of democracy, Mr. Escobar says.

The trade-offs

Nearly 82% of Salvadorans say they’re prepared to vote Mr. Bukele and his Nuevas Ideas party into a second presidential term, despite a constitutional ban on reelection.

But as the state of exception continues, support for Mr. Bukele could dip, says Ingrid Escobar, founder of Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, a local NGO.

“This is a relative peace. It’s costing us our human rights, freedom, and democracy,” she tells the Monitor following a press conference where she publicly denounced the wrongful imprisonment under the state of exception of a young man, Marco Antonio Rivera, who is deaf and uses sign language to communicate.

He was detained in June for allegedly using gang symbols. Human rights advocates say the state has criminalized his disability.

The more innocent people are caught up in this militarized approach, denying them due process, the more society will think critically about the stakes and solutions, Ms. Escobar believes.

And many experts question what will happen once the state of exception is lifted. Civil liberties likely can’t be suspended indefinitely, and a policy that centers on imprisoning tens of thousands of people is prohibitively expensive.

“The gangs are a consequence, not the origin” of El Salvador’s security challenges, says Mr. Escobar. “There has been no government activity ... to attack inequality, poverty, or to generate opportunities, employment,” he says.

Nearly 3.25 million Salvadorans – roughly half the population – face moderate to severe food insecurity, according to the United Nations. Between 2018 and 2022, the number of Salvadorans living in extreme poverty has risen.

For the mother of Mr. Rivera, the man detained for using sign language, just thinking about this weekend’s vote has her on the verge of tears.

“When he was taken away, my son was wearing a Nuevas Ideas bracelet,” identifying him as a supporter of Mr. Bukele’s party, she says. “I don’t know what the answer is, how to vote. I’m asking God to intervene.”

Today’s news briefs

• EU aid for Ukraine: European Union leaders unanimously agree to extend €50 billion ($54 billion) in new aid to Ukraine, overcoming resistance from Hungary. Several cast Russia’s war in Ukraine, Europe’s biggest conflict since World War II, as an existential challenge.

• U.S. House votes on tax breaks: A roughly $79 billion tax-cut package, which passed Jan. 31 with bipartisan support, would enhance the child tax credit for lower-income families and boost three tax breaks for businesses. The Senate has yet to take it up.

• U.S. assigns drone-attack blame: Washington attributes the attack, which killed three U.S. service members in Jordan, to the Islamic Resistance in Iraq, an umbrella group of Iran-backed militias, as President Joe Biden weighs his options to respond.

• Greta goes to court: Climate activist Greta Thunberg is on trial in the United Kingdom after protesting outside a fossil fuel industry conference in London last year. The 21-year-old Swede and other protesters pleaded not guilty to charges of breaching a law that allows police to limit public assemblies.

In Gaza, humanitarian network in crisis as people’s needs soar

The humanitarian needs of Palestinians in Gaza, displaced by war and facing dwindling access to food and shelter, are staggering. Now Gaza is also facing a crisis in its aid distribution network.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ghada Abdulfattah Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

The complex military, political, and logistical challenges to getting food, shelter, and medical supplies into Gaza are leaving the vast majority of Palestinian residents competing for limited resources. Money is scarce, and there’s little to buy.

Now there’s a new, urgent obstacle: the defunding of UNRWA, the distributor of more than 50% of aid in Gaza. Several donor nations pulled their funding for the relief organization after Israeli intelligence alleged that 12 of its 13,000-member Gaza staff were involved in Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack.

UNRWA, which opened an investigation and terminated the employment of nine of the 12 accused, warns it is set to shut operations in Gaza and across the region by the end of this month.

“Shutting down UNRWA will dramatically compromise the humanitarian response immediately,” warns Andrea De Domenico, head of the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the occupied territories.

At a makeshift gold stand on a Rafah street, women sell the last of their jewelry to feed their families.

Asma says she is desperate to sell her gold bracelets – at a discount – because “there is no sign of this war ending.”

“I had saved these bracelets to invest in my children’s future,” she says, “but now I am selling them for food.”

In Gaza, humanitarian network in crisis as people’s needs soar

In a makeshift tent in Rafah, Habiba Abu Bazazo uses kindling to boil wheat for her family’s meal in a tiny borrowed skillet.

The family’s consumption is down from three square meals a day to a single meal of two ingredients – if they’re lucky.

“We are being crushed by the weight of scarcity,” the mother of four says. “Every meal needs a budget.”

The complex military, political, and logistical challenges to getting food, temporary shelter, and medical supplies into the Gaza Strip are leaving the vast majority of Palestinians competing for scarce resources with little cash in a wartime economy.

Now there’s a new, urgent obstacle: the defunding of UNRWA, the facilitator and distributor of more than 50% of aid in Gaza.

Several donor nations pulled their funding of the United Nations’ Palestinian relief organization in the past week after Israeli intelligence alleged that 12 of UNRWA’s 13,000-member Gaza staff were involved in Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack.

U.N. officials say the defunding will have a “devastating impact,” and UNRWA opened an investigation and terminated the employment of nine of the 12 accused; the other three employees are dead or missing.

The agency is set to shut down operations in Gaza and across the region by the end of this month, UNRWA Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini warned Thursday.

“Shutting down UNRWA will dramatically compromise the humanitarian response immediately,” warns Andrea De Domenico, head of the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the occupied territories, which directs the U.N. and non-U.N. Gaza aid response.

Backbone of aid response

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East was founded to aid Palestinian refugees after the 1948 war that followed the creation of Israel. It provides health, education, and housing to some 5 million Palestinians in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, and the occupied territories.

It plays a huge role in Gaza. As of this week, UNRWA facilities house more than 1.2 million displaced Palestinians across the narrow coastal strip, over half of Gaza’s population. It distributes flour, canned food, and basic hygiene kits for the entire population of 2.2 million.

The agency, reliant on voluntary donations from U.N. member states, is also a main provider of water. It runs desalination plants and seven wells, and has delivered 20 million liters of drinking water since the Israel-Hamas war’s start. It currently is the sole agency bringing Gaza fuel, which it distributes to other humanitarian agencies, desalination plants, and medical facilities.

Critically, the U.N. and international humanitarian organizations rely on UNRWA warehouses, logistical networks, and staff to get aid to displaced families throughout the besieged strip.

Nine Western nations led by the United States, UNRWA’s largest single donor, have announced they had suspended further contributions, which would deprive the agency of $440 million of its $1.2 billion budget. The U.S. State Department said it would not complete its annual $300 million-$400 million contribution, of which $121 million had already been paid.

On Wednesday U.N. agencies and other international organizations warned that the funding suspensions “will have catastrophic consequences for the 2.2 million people of Gaza.”

“UNRWA will not be able to purchase the food, hygiene, and medicines we are currently buying or have the personnel” to distribute it, says Juliette Touma, UNRWA director of communications.

According to the humanitarian affairs office, it will take “weeks” to figure out logistics to replace UNRWA, a process which could grind an already beleaguered aid response to a halt.

The U.N. is currently struggling to get aid beyond Rafah, with limited fuel, communications, and Israeli movement restrictions that have at times blocked convoys and require cargo to be loaded and unloaded from trucks several times before reaching it destination.

Under the current conditions, the international community can barely get more than 200 aid trucks a day into Gaza.

Not only does this restrict organizations’ ability to reach affected areas, “but also the affected population’s ability to access assistance,” Mr. De Domenico says.

“It is not just a question of how many trucks,” he says of the logistical challenges. “The entire machinery of the response is being affected.”

Impact of fighting

Meanwhile, intense fighting this week in Khan Yunis, which emptied an UNRWA center hosting 43,000 evacuees, pushed tens of thousands more people into Rafah, what U.N. officials describe as a “gigantic human wave.”

Tents are crammed all the way to the southwestern edge of the strip, pushed up against the Egyptian border.

Families scramble for makeshift tents as heavy rains and cold temperatures hit the coastal enclave; winter clothes are an urgent need; children walk around Rafah and central Gaza barefoot, in shorts and T-shirts.

Palestinians in Gaza are forced to rely on money wired from relatives to buy what scarce supplies are left in markets. A pack of biscuits that went for $0.15 now sells for $2; a $1 kilogram of onions commands $13.

Most families, without wood or access to a space to cook, need cash to pay entrepreneurial women to bake their flour and children to grind their grain.

In Gaza, if a family wants to eat, they have to pay.

In Rafah, men and women wait in separate milelong lines that converge at the Barasi International Currency Exchange, one of the two last functioning exchanges in Gaza that can receive money wires.

“I need a miracle”

Ms. Abu Bazazo, the displaced mother of four, made her fourth attempt in a week to retrieve a transfer from her family in Jordan, pending for 20 days.

She secured her place in line after dawn prayers at 5:30 a.m.; at 9 she had barely moved.

“I recognize many of the women standing alongside me from yesterday and the day before,” she says. “There was no internet for seven days. ... I need a miracle.”

Hours later, the exchange owner announced there was no cash available.

“I have to go home empty-handed,” Ms. Abu Bazazoi says with a sigh. “My children asked me for food.”

U.N. staff say some people in Gaza are selling the limited food aid they receive to buy medical supplies, winter clothes, or materials to build their own tents.

At a makeshift gold stand on a Rafah street, women sell the last of their jewelry and wedding dowries for cash to feed their families.

Among them is Asma, who declined to give her last name. She waits for the “jeweler” to weigh gold bracelets she was desperate to sell – at a discount – because “there is no sign of this war ending.”

“I had saved these bracelets to invest in my children’s future,” Asma says, “but now I am selling them for food.”

Crypto was to address a collapse of trust. But can it be trusted?

Cryptocurrency emerged to address the world’s fading trust in traditional institutions. But to fulfill its revolutionary promises, crypto might need to learn some old-school lessons.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Cryptocurrency emerged from the ashes of the financial crisis that ended in 2009. No longer would regular people have to trust fallible banks or intermediaries in order to spend their money online. They could put their faith in the mathematical code behind cryptocurrency.

Since then, that digital breakthrough, called blockchain, has been heralded as a potential solution in areas from cybersecurity to voting. Yet the crypto world now has its own trust problem. Recent years have showed that crypto is vulnerable to the same kinds of foibles that gave it momentum during the financial crisis. It can be a Wild West where volatility, scams, and illicit activity thrive.

The promise is real. The United Nations World Food Program saved $3.5 million in fees by sending humanitarian aid via a private version of one cryptocurrency to more than a million refugees in Bangladesh, Jordan, Lebanon, and Ukraine. Researchers funded by the European Union are exploring ways blockchain can restore confidence in public and private institutions.

The great experiment, says Nathan Schneider, a professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, is to see if we can build a decentralized, mathematical system in which we’re “actually trusting each other more.”

Crypto was to address a collapse of trust. But can it be trusted?

Cryptocurrency emerged from the ashes of the 2007-2009 financial crisis to solve a problem of trust. Not to renew faith in a collapsed banking system or to reverse decades of plummeting trust in government and other institutions.

It promised an end to the need for trust at all.

No longer would regular people have to rely on banks or intermediaries in order to spend their money online. Cryptocurrency offered a new system based on “cryptographic proof instead of trust,” as Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous inventor of bitcoin, announced in a white paper presenting the concept. Rather than trusting fallible human institutions, private citizens could put their faith in mathematical code alone.

And why should people do that? Because of the blockchain, a digital chain of uneditable information that is verified by every participant in a decentralized way, with no single governing power. Transactions are anonymous and difficult to track.

Fifteen years later, cryptocurrency has swelled into a $1.71 trillion global market, up from its crash in 2022. A quarter of Americans own bitcoin. And blockchains are being explored as solutions in areas from cybersecurity to voting and corruption prevention.

Yet the crypto world has its own trust problem. The underlying code is largely sound. But recent years have shown that crypto is vulnerable to the same kinds of foibles that first gave it momentum during the financial crisis. It can be a Wild West where volatility, scams, and illicit activity thrive.

With tens of thousands of cryptocurrencies on the market – some purely speculative, some offering real value – the question now is whether crypto can build the legitimacy it needs to deliver on its promises. And in a curious irony, the old-school banking system might offer clues.

“If crypto really wants to make good on this promise of a more just system, that also needs to include the things that make a society trustworthy,” from deposit insurance to human rights protections, says Nathan Schneider, assistant professor of media studies at the University of Colorado Boulder.

At the same time, he is cautiously hopeful about the possibilities for using blockchains to make processes more transparent and reliable, from banking to democracy. The people working in that realm are “not really trying to eliminate trust,” he says. “They’re trying to create systems that can facilitate people building decentrally governed entities and actually trusting each other more.”

Two views of cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrency means a lot of things to a lot of people. Most crypto buyers in recent years aren’t in it to liberate the world from the prying eyes of government. Instead, they see a chance to make – though many lose – large sums of money. Hype cycles are quick to form around new coins whose main purpose is speculation, opening the door to scams and fraud.

“A lot of the same problems that led to that original crisis have really been replicated in the crypto world,” says Molly White, who tracks crypto-related scandals on her website, Web3 Is Going Just Great.

She points to dubious financial products and a lack of awareness about how money is being used. One of the biggest cryptocurrency traders, FTX, collapsed in late 2022 after news of the founder’s misuse of customer funds came to light.

The space has become a “giant, unregulated casino,” that “preys on people’s mistrust of institutions,” adds Ethan Zuckerman, a media scholar at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

For some crypto enthusiasts, that might be fine. They might prefer that it be a rogue system on the fringe. For them, “the lack of trust is sort of a feature, not a bug,” says Lana Swartz, an associate professor of media studies at the University of Virginia.

For others, however, that’s all froth on the surface of a powerful innovation still in its early days. Ethereum, the second-most-valuable cryptocurrency behind bitcoin, has a large and loyal following of people excited about how blockchains can transform the ways society governs itself in the future.

The United Nations World Food Program saved $3.5 million in fees by sending humanitarian aid via a private version of ethereum to more than a million refugees in Bangladesh, Jordan, Lebanon, and Ukraine. And researchers funded by the European Union are exploring ways blockchain can “restore confidence” in public and private institutions.

Boring may be good

So far, cryptocurrencies have gained the most ground in places where the existing alternative is even less trustworthy.

Gabriel Álvarez was a teenager during the 2001 financial crisis in Argentina and has watched the country’s currency plummet in value during the past decade. Following the 2019 presidential election, he stood in line for hours at three banks across Buenos Aires before finding one with enough money to give him his life savings. He took the wads of cash and invested in bitcoin, ethereum, and anything besides the Argentine peso itself.

Cryptocurrency offered relative stability and, at first, the promise of earning something. But “over time, I’ve lost confidence in crypto as an investment,” says the software developer.

Today he keeps one-fifth of his savings in cryptocurrency, which he uses to pay rent to his landlord, who lives in Brazil.

Even El Salvador, which adopted bitcoin as legal tender in 2021, has had a hard time getting its citizens on board. To earn trust worldwide, cryptocurrency may need to become more boring.

That’s the idea behind stablecoins, a type of cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to real currency, typically the U.S. dollar. Together these coins make up the third-largest share of the cryptocurrency market.

An early mistake was to assume crypto entrepreneurs could go without “the same levels of self- and government regulation that traditional financial services have come to understand is vital,” says Josh Burek, senior director of strategic positioning for Circle, which issues a stablecoin called USDC.

While regulation in the United States is still lagging, there are signs that cryptocurrency is institutionalizing. The Securities and Exchange Commission hesitantly approved the first exchange-traded funds to hold bitcoin last month.

Few believe cryptocurrency will ever replace the basic building blocks of a stable economy, such as governance and a reliable legal system.

But the technology may still open interesting doors, says Eric Budish, an economist at the University of Chicago. While he doesn’t think cryptocurrency is a viable economic solution at a global scale, “there’s a lot of scope for innovation and how to marry some of the intellectual ideas that have been bubbling up with crypto to traditional sources of trust.”

Israel’s Netanyahu fights against Hamas, and for his future

For Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, the war in Gaza is about more than destroying Hamas. It is also about a struggle for political survival.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

The war in Gaza – 4 months old, imposing terrible suffering on both sides, yielding no definitive victor, and promising no visible endpoint – is being propelled by a dizzying array of regional rivalries and interests.

But one thing, more than any other, could decide how long the war rages and how it ends. The Benjamin Netanyahu factor. For the Israeli prime minister, it’s also a matter of political survival, and he is waging the war with electoral considerations in mind.

That has put him at odds this week with his closest ally, the United States, over issues ranging from the way Israeli troops are fighting the war to the shape of a post-war Gaza. But Mr. Netanyahu wants to dust off his image as a no-nonsense strongman leader, and his determination to destroy Hamas is shared by most Israelis.

So long as that is the case, Washington will find it hard to engage him in talks about Gaza’s future and Palestinian governance.

Unless, perhaps, the U.S. appeals to his self-interest. If peace with the Palestinians came in a package with peace with Saudi Arabia, that second achievement, long sought by Israeli leaders, would lift Mr. Netanyahu into the ranks of historic peacemakers.

Israel’s Netanyahu fights against Hamas, and for his future

The war in Gaza – 4 months old, imposing terrible suffering on both sides, yielding no definitive victor, and promising no visible endpoint – is being propelled by a dizzying array of regional rivalries and interests.

Yet one thing, above all, could determine how long the war rages, and how it ends.

It’s the Benjamin Netanyahu factor.

For Mr. Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, the war in Gaza is not only a response to the abuse, abduction, and killing by Hamas of more than a thousand civilians across southern Israel on Oct. 7 last year.

It is also a struggle for political survival, after presiding over the single greatest security failure in Israel’s history.

With the outlines of Mr. Netanyahu’s bid to stay in office growing steadily clearer, this other war has complicated U.S. efforts this week to mediate a new cease-fire and a hostages-for-prisoners exchange between Israel and Hamas.

It’s also contributing to U.S.-Israeli tensions over a range of other issues: how the war is being fought, how best to mitigate the deepening humanitarian crisis facing Gaza’s 2 million civilians – and, critically, how Gaza will be rebuilt, and governed, when the fighting finally ends.

That’s because Mr. Netanyahu is staking his future on two political calculations.

The first: that he can dust off his unrivaled brand as a no-nonsense strongman leader, ready and willing to face down not only Israel’s enemies but also, when necessary, its key allies, including the United States.

The second: that he can defer a reckoning for the events of Oct. 7, particularly an early election, by retaining his parliamentary majority. That majority depends on far-right politicians who favor permanent Israeli control over both the occupied West Bank and Gaza.

Survival won’t be easy. Mr. Netanyahu’s poll numbers have tanked since Oct. 7. A survey in January found a scant 15% of voters wanting him to remain prime minister once the war ends.

Opposition leaders who joined him in an inner Cabinet after the Hamas attack have begun questioning the viability of his declared war aim – total victory and the destruction of Hamas in Gaza; they are advocating a cease-fire deal to free the remaining Gaza hostages.

The families of the hostages have also been pressing the prime minister to prioritize their welfare.

If the U.S. and its Qatari and Egyptian partners do manage to persuade Hamas to accept such an arrangement, Mr. Netanyahu would be forced to make a difficult political choice. Refusing a deal would risk breaking up the inner war Cabinet, which could hasten a new election. Accepting it would probably prompt the defection of his extreme-right coalition partners, which could also force a reckoning with the voters.

Still, there are powerful reasons for Washington to keep seeking common ground with Mr. Netanyahu.

He is not merely the sitting prime minister. He has also proven to be Israeli politics’ great survivor.

Since the 1990s, weathering a pair of election defeats along the way, he has been in power for a total of 16 years.

When Hamas attacked last October, he was already wrestling with challenges that would have sunk many another politician.

He was – and still is – facing court cases on charges of corruption and breach of trust.

In order to assemble his governing coalition in 2022, he had included the most extreme-right ministers ever empowered in Israel. When he attempted a “judicial reform” aimed at limiting government oversight by the Supreme Court, hundreds of thousands of Israelis took to the streets to protest what they saw as the unraveling of Israel’s democracy.

Yet within hours of Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, he redefined Israeli politics around what he portrayed as an existential war to obliterate Hamas in Gaza. And that narrative – if not Mr. Netanyahu’s leadership – has been embraced by a large majority of Israelis.

This narrative could begin to crumble, weakened by the welfare of the hostages, perhaps, or by first-hand misgivings about the war among the many reserve troops rotating out of Gaza.

Still, as long as it holds firm, the Americans and their regional allies seem to recognize that there is little chance of persuading Mr. Netanyahu to engage with them on how to bring the war to an end, much less on the question of Gaza’s, and the Palestinians’, political future.

Unless the allies appeal to his self-interest. Their main hope may well rest on convincing him of an endgame that would benefit not just Israel and the wider Middle East, but his own political fortunes as well.

The geopolitical imperative, as Washington sees it, is already clear: to revive the Gaza Strip with the help of international support and billions of dollars from leading Arab countries in the Gulf, under a reconfigured Palestinian political leadership as part of an eventual two-state peace arrangement.

That formula, it is hoped, would bring regional stability – and offer a viable, long-term alternative to the “resistance” message from Iran and proxy armies like Hamas and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

But at its core would also be a formal peace between Israel and Saudi Arabia, the leading Arab and Islamic state.

That prize, long sought by Israeli leaders, would lift Mr. Netanyahu into the ranks of historic peacemakers.

Perks and perils of being married to a photographer

Sometimes a vacation is just a vacation. Unless your traveling partner is The Photographer. Then it’s a work of art waiting to happen – if you’re game to play along.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Michael S. Hopkins Contributor

-

Melanie Stetson Freeman Staff photographer

Perhaps it’s not obvious, but my marriage to The Photographer involves occupational hazard. The occupation being hers. The hazard(s) being mine.

You might be hiking the coast of Kauai, say, when suddenly she indicates that it would be useful for you to stand across the way (she is pointing) on that promontory of crumbling lava above pounding surf. The waves, you observe, routinely shatter up and over said promontory.

“I’ll get soaked,” you say.

“You’ll dry,” says The Photographer.

So you go. Of course you go.

Because a little stage-managed derring-do is no price at all for access to something priceless: a new way of looking. Of noticing. Of seeing things and people and places and light – and out of them making compositions that wordlessly speak. The way The Photographer does.

Expand this story to experience the full photo essay, as The Photographer intended.

Perks and perils of being married to a photographer

Perhaps it’s not obvious, but my marriage to The Photographer involves occupational hazard. The occupation being hers. The hazard(s) being mine.

After all, one never knows when The Photographer will require of one a feat of athleticism, or daring. Lean out over there, hold up that, jump through those. Go sit by that angry peacock.

Or you might be hiking the coast of Kauai, say, when suddenly she indicates that it would be useful for you to stand across the way (she is pointing) on that promontory of crumbling lava above pounding surf. The waves, you observe, routinely shatter up and over said promontory.

“I’ll get soaked,” you say.

“You’ll dry,” says The Photographer.

So you go. Of course you go. You’ve long since learned that there are always three of you present: There’s you, there’s her, and there’s the camera. You’ve learned that sacrifices must be made. For art.

I’m not complaining. (Does it sound like it?) Because a little stage-managed derring-do is no price at all for access to something priceless: a new way of looking. Of noticing. Of seeing things and people and places and light – and out of them making compositions that wordlessly speak. The way The Photographer does.

So yeah, sometimes you wait. And sometimes you get covered in ocean. Yet it excites you every time – because in the end, of course, you get pictures. Magnificent pictures. Like these.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Saving Ukraine in Hotel Amigo

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One of the most world-shaping negotiations took place this week in Hotel Amigo, a popular place in Brussels for European officials to stay. In one-to-one meetings and a group session, the continent’s top leaders overcame frosty relations with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and convinced him to drop his opposition to $54 billion in financial support for Ukraine.

The deal announced Feb. 1 by the 27-member European Union not only will uplift Ukraine’s defenses against Russia but also might spur the U.S. Congress to end its political disputes over further funding for Kyiv. It also sends a message to Russian President Vladimir Putin that democratic discourse, when done in good faith among those with equal rights around the table, remains a model for the world.

A key principle of international relations is that countries negotiate in good faith, not out of revenge or to humiliate, but to create a space for finding shared interests, even perhaps shared values. Sincere deliberation can be more than winning arguments. The mere act of listening to others requires a posture of equality, the essence of democracy. And that is what Ukraine is fighting for. And something that Hungary is supporting, too.

Saving Ukraine in Hotel Amigo

One of the most world-shaping negotiations took place this week in Hotel Amigo, a popular place in Brussels for European officials to stay. In one-to-one meetings and a group session, the continent’s top leaders overcame frosty relations with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and convinced him to drop his opposition to $54 billion in financial support for Ukraine.

The deal announced Feb. 1 by the 27-member European Union not only will uplift Ukraine’s defenses against Russia but also might spur the U.S. Congress to end its political disputes over further funding for Kyiv. It also sends a message to Russian President Vladimir Putin that democratic discourse, when done in good faith among those with equal rights around the table, remains a model for the world. It can’t be suppressed by invading other countries or squelching dissent.

The Hungarian leader, who is close to Mr. Putin, certainly felt pressure from other EU leaders to support more aid for Ukraine. And the negotiations did require some balancing of national interests, such as the release of some EU funds for Hungary after reforms to its judiciary.

But as Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar said of the talks, “We have a system of unanimity for making big decisions here in Brussels, but it’s on the basis that everyone acts in good faith and is willing to make compromises” on issues that are for “the greater good.”

Ukraine has also held direct talks with Hungary in recent days on a number of bilateral issues. The tone was one of empathy and openness, the elements of trust.

“We spoke frankly about our fears about each other’s intentions. We explained everything to each other,” said Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba. “The Hungarians distrust us, we distrust them – due to different circumstances, that’s understandable. And the fact that we discussed all this today ... I believe that this is very important.”

A key principle of international relations, laid down in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, is that countries negotiate in good faith, not out of revenge or to humiliate, but to create a space for finding shared interests, even perhaps shared values.

Sincere deliberation can be more than winning arguments or angling for more power. The mere act of listening to others requires a posture of equality, the essence of democracy. And that is what Ukraine is fighting for. And something that Hungary is supporting, too.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Christ’s action is thorough

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Constance Watkins

As Christ Jesus showed us, we can count on divine Truth to clear away thoughts that don’t align with God’s goodness – and healing follows.

Christ’s action is thorough

In the scriptural book of Luke, John the Baptist tells his followers of the coming of Christ Jesus, and he describes him as the one who will baptize “with the Holy Ghost, and with fire.” Using the metaphor of a threshing fan, which separates the chaff from the wheat, John says of Christ Jesus that his “fan is in his hand, and he will throughly purge his floor, and will gather the wheat into his garner; but the chaff he will burn with fire unquenchable” (3:16, 17).

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, defines “fan” as “separator of fable from fact; that which gives action to thought” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 586). Christian Science declares as fact the overarching New Testament message that God is good, pure Spirit, and all power.

As God’s image and likeness, man must be spiritual and subject only to God’s all-good power. Whatever opposes this fact must be a powerless fable, cast out through the purifying action of Christ, the true idea or understanding of God.

“He will throughly purge his floor.” According to “Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance of the Bible,” the Greek word translated “throughly” in this verse means “to cleanse perfectly.” In considering this, I saw that it points to the healing action of the Christ, which comes to destroy the ills of the flesh. It shows this divine, healing action to be complete, leaving no lingering trace of chaff or worthless debris, no unhealed residue, no false thought uncorrected, no stone or obstacle not rolled away.

Jesus’ widespread teaching, preaching, and healing mission demonstrated that this purifying, healing action of the Christ fan is irresistible, irrepressible, unstoppable, and perpetual. Mrs. Eddy also states, “Jesus’ demonstrations sift the chaff from the wheat, and unfold the unity and the reality of good, the unreality, the nothingness, of evil” (Science and Health, p. 269). With fan in hand, Christ allows no evil belief or fear to infect consciousness but cleanses it perfectly of all that is unlike the divine Mind, God.

With Christ at the door of our thinking, no claim of evil or fear can prevent us from opening our thought to “the unity and the reality of good, the unreality, the nothingness, of evil.” In fact, in that divine reality of infinite good there is no evil, mental or otherwise.

From beginning to end the Bible records God as speaking to His children – inspiring, guiding, correcting, and guarding them in the Christly way – and always revealing the perfect solution.

One night my daughter woke me, crying that her ear was hurting. We went to her room, where I tucked her in and began talking about God. I reminded her of His allness and goodness, His harmonious action, and what therefore must be spiritually true about her as God’s image and likeness (see Genesis 1:26, 27). Because she reflects God, I knew she could never be influenced or touched by anything He didn’t cause.

My daughter then shared something she had been learning about God in the Christian Science Sunday School – how He never made sickness or pain.

Then we got quiet and listened for what God had to say. After a few minutes, this idea came to me very clearly: There is no irreversible error, no insoluble problem. I felt such peace, and I heard my daughter say that her ear was draining. Then, as I was cleaning the ear, she said she couldn’t hear out of it.

Acknowledging that the Christ fan, or action, is always thorough, we continued to pray until, suddenly, she reported a “pop” in the ear and said she could hear perfectly.

We rejoiced, thanked God, and she went to sleep for the rest of the night. There was never a return of this problem. The Christ, Truth, had throughly fanned it away as totally reversible and solvable because God, Truth, could not make anything that isn’t like Him, good.

Adapted from an article published in the Nov. 2, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Ain’t it grand!

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow for an in-depth look at the very Swedish concept of “lagom.” Staff writer Erika Page finds that, in some ways, it reflects a universal yearning for connection, “enoughness,” and trust. You can read our cover story from the Weekly magazine, as well as listen to Erika discuss the topic in our “Why We Wrote This” podcast.