- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A country shaken

Many have said that Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack shook Israelis to their core. But what does that mean? In our first story, Howard LaFranchi, as Middle East Editor Ken Kaplan puts it, “takes you to that core.”

Howard has been visiting Israel regularly since the attack, building a deeply reported portrait of the dynamics coursing through society. Even if you think you know Israel, you’ll want to read this story.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Five ways Israel is changing after six months of war in Gaza

Civil society’s response to Oct. 7 is planting the seeds of a new political class. But what Israelis see as the worst day in their history is also profoundly challenging their sense of security and belonging.

It may be counterintuitive, after Israel was torn in the months leading up to the war in Gaza by massive demonstrations, but a return to such protests is being viewed by some as an almost welcome return to normalcy. In many respects, however, the country is still reeling from Oct. 7, 2023.

Six months and counting into the war against Hamas, observers point to five notable changes to Israel and Israelis wrought by the war.

There’s the lingering trauma of Oct. 7, which is still blinding Israelis to the suffering of Palestinians in Gaza; feelings of abandonment, first by their government, then by the world; and an urge to “go it alone” that threatens Israel’s acceptance in the world.

Potentially more hopeful are the resurgence of attention to Palestinians’ needs and the two-state solution, and the seeds of a new political class planted by the response to Oct. 7.

“To some degree, we have returned to the ‘regularly scheduled program’ of life as it was on Oct. 6, but at the same time, we are still dealing with dark fears that have us stuck,” says Nimrod Novik, a former foreign policy adviser.

Five ways Israel is changing after six months of war in Gaza

When the Brothers in Arms organization announced at a Tel Aviv rally last month that it was returning to anti-government protests, ending a post-Oct. 7 hiatus, it was taken by some Israelis as a hopeful sign.

Maybe Israel was starting to recover and find some semblance of normalcy after that terrible October Saturday when Hamas fighters crossed from Gaza, killed mostly unarmed civilians, took hostages, and forced Israelis, for the first time in their history, to abandon large swaths of national territory.

Brothers in Arms, a reservist group, had surged onto the national scene in early 2023 as part of huge pro-democracy protests against government plans to overhaul the judiciary.

But after Oct. 7 it became known for transforming overnight into something of a shadow civilian service corps, providing food, shelter, and even counseling services to those most affected by the attack, filling in for what many evacuees felt was an absent state.

Now it was resuming demonstrations.

“The only way to get things done here is through protest,” Omri Ronen, a captain in the army reserves, announced at the rally. “This may be our last opportunity, and we must not lose it.”

Whether the protests constitute a sign of recovery is open to debate. What seems clearer, experts and social observers say, is how the civil society response to Oct. 7 is planting the seeds of a new political class.

That development is just one of the changes – some heart-wrenching and worrisome, some hopeful – these experts are sensing six months after what is widely viewed here as the worst day in Israel’s history.

Politically, Israeli society has shifted right, most say, as the country finds itself bogged down in Gaza in its longest war and engaged in a lethal sparring match with Hezbollah, Iran’s powerful regional ally, to its north.

Israel’s war with Hamas has devastated much of Gaza and left tens of thousands of Palestinians dead. The United Nations has declared famine there no longer just a threat but a reality.

Rising militarism has silenced efforts at forging peaceful coexistence with Palestinians. Soldiers are the romantic heroes of the moment, with young women on dating apps seeking out reservists posting photos of themselves in Gaza. Surging gun ownership underscores a loss of faith in the state’s ability to protect citizens.

Also discernible are hints of other profound shifts that could have lasting impact on Israel domestically – and on its relationship with friends and foes outside, even if some say it’s too early to draw firm conclusions.

“Israelis are still coming to terms with the stunning realization that for the first time in our independence, a part of Israel was occupied by brutal terrorists,” says Nimrod Novik, former senior foreign policy adviser to Shimon Peres, the late Labor party prime minister.

“We are living what I would call a time of national schizophrenia,” he adds, “when to some degree we have returned to the ‘regularly scheduled program’ of life as it was on Oct. 6, but at the same time we are still dealing with dark fears that have us stuck.”

Still others say it’s too soon to expect progress.

“Six months can be a long time, but in this case it’s not,” says David Enoch, a philosopher and past professor of ethics and law at Hebrew University who is now on the law faculty at Oxford. “The healing has not yet begun.”

Yet these same observers say they see a number of significant ways Israel has changed. Five stand out:

1. A lingering – and blinding – trauma

“The fact that so many Israelis have been traumatized by that day and are still suffering that trauma has left them unable to have a serious moral conversation even with our [foreign] friends,” says Yossi Klein Halevi, a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. “That is contributing to this downward spiral” in Israel’s relations with the world, he says.

A significant piece of what some describe as a nonstop nightmare is the fact that Hamas still holds more than 130 hostages in Gaza – although their condition and how many are alive are unknown.

Dr. Enoch says this trauma has rendered Israelis unable to see beyond Oct. 7 – a day intended to destabilize Israel’s very existence – to the human tragedy Israel has inflicted on Gaza.

“I hear from thinkers on the left, like me, things like, ‘I have no place in my heart for the children of Gaza,’” he says, “and I realize we are nowhere near the point of coming to terms with this.”

If anything encourages Mr. Halevi, however, it is a growing sense that Israelis want to move beyond the trauma.

“Israeli opinion has definitely hardened in the last months,” he says. “But at the same time, there is a desire for healing – so that gives me hope.”

2. Feelings of abandonment: by the government, and a world that has forgotten Oct. 7

“People realized very quickly that what we already knew was a mediocre government at best was actually worse; it was absent,” says Einat Wilf, a former Labor member of the Knesset and co-author of “The War of Return” on Israeli-Palestinian peace.

“But now added to that despair is another deep sense of despair at seeing so many in the world forget what happened here,” she adds, “and buckle under the weight of lies and accept anything being said about Israel.”

That growing sense of abandonment by the world, Mr. Halevi says, has left Israelis defensive and uninterested in hearing legitimate critiques of Israel’s conduct of the war in Gaza.

“There is a great gap between saying Israel is fighting a just war in an unjust way, and saying Israel is committing a genocidal war,” he adds. “I worry that Israelis are increasingly unable to distinguish between the legitimate moral questions of our friends and the outrageous criticisms from our enemies.”

Israel was already accustomed to a sense of aloneness, Ms. Wilf says. But the abandonment is felt most acutely concerning shifting perceptions of Israel in the United States, and the impact that has on U.S. support for the war on Hamas.

“The despair we already felt only goes deeper as we realize the United States wants to shut down the war,” she says, “and leave us in a situation where Hamas is left standing.”

3. The post-Oct. 7 urge to “go it alone” that threatens the Zionist dream of Israel’s acceptance

Just days before the Oct. 7 attack, a hot topic of conversation in Israel was the prospect of normalizing relations with Saudi Arabia – and what that would mean for Israel’s long march to international acceptance.

Today many Israelis, backed by official rhetoric from Benjamin Netanyahu’s hard-right government, talk more about a new willingness for Israel and indeed the Jewish people to “go it alone.”

And that has some deeply worried about what they see as a “downward spiral” in Jews’ global status after decades of progress since World War II and Israel’s founding in 1948.

“The promise of Israel being founded after the Holocaust was that the exile was over, and that Jews could now live free from that terrible sense of aloneness,” says Mr. Halevi. “The central purpose and promise of Zionism for the Jewish people was not only our ability to defend ourselves,” he adds, “but a new relationship between ourselves and the rest of the world.”

And Israel has experienced growing acceptance, he says – especially in the Middle East.

“What worries me six months after Oct. 7 is that the historic achievement of Zionism is being undone, [that] we are going to see the psychological impacts on Israelis and Jews around the world of the revival of this sense of aloneness.”

What many Israelis see is a world where the movement to criminalize Israel is “going mainstream,” Mr. Halevi says, and where the “progressive world” is moving “perilously close to becoming the biggest source of antisemitism.” But the more Israel is treated as a “pariah state,” he says, the more justified the right wing in power feels in “shaping policies that further turn the world against Israel.”

The troubling result, he says, is “they [the right] are making the Jewish people’s growing aloneness a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

4. Resurgence of the Palestinian question and the two-state solution

Behind the recent uptick in normalized relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors – of which normalized Saudi ties were to be part – was the idea that Palestinian national aspirations could be shunted to the side and treated separately.

For some Israelis, largely among the Israeli Arab minority, Oct. 7 was a wake-up call that peace and regional progress won’t come without the Palestinians.

“I’m very sorry we had to have this terrible disaster to remind people of something so basic as the untenable aspect of having [millions of] Palestinians living under military control and repression,” says Rula Hardal, a political scientist at the Shalom Hartman Institute who is a Palestinian citizen of Israel.

“If we can say that anything positive has come out of this,” she adds, “maybe it is that the Palestinian issue is again on the global agenda and people are remembering that we cannot create regional peace without addressing the question of Palestinian national sovereignty.”

Dr. Hardal, an executive director of A Land for All, an organization that advocates for an Israeli-Palestinian confederation, says she is encouraged by increased discussion internationally of the need for a two-state solution: a state of Palestine alongside Israel.

On the other hand, she is not convinced there is much of substance behind the Biden administration’s rhetorical support for two states. “They are talking about it more, but when I hear what the Biden administration is saying it seems they don’t mean anything serious.”

Moreover, she notes that if anything, Israeli opposition to a Palestinian state is stronger than before Oct. 7.

Longtime Israeli advocates of a Palestinian state say it simply isn’t useful to make that case now.

“Even those of us who have not lost sight of the two-state solution despite the current context are careful to adjust our advocacy to the national mood,” says Mr. Novik, senior Israel fellow with Israel Policy Forum, a Washington-based think tank. “Any talk of [it] right now is so detached from most Israelis’ reality that it is just not constructive.”

While Dr. Hardal concurs that the moment isn’t ripe for progress, she also rejects any notion that circumstances render understandable one nation’s rejection of another’s right to sovereignty.

“Personally I accept and support that every group of people has the right to claim their nationhood, and that includes the Jewish people,” she says. “What I cannot accept is that the Jewish people would deny Palestinians their right to sovereignty. And unfortunately,” she adds, “what we see in recent months is this rejection getting stronger.”

5. The seeds of a new political class planted

Perhaps the most promising post-Oct. 7 development is a new class of Israeli political leaders and a revaluation of public service and the role it plays in strengthening society.

The civilian infrastructure that evolved with the pro-democracy protests of 2022-23 was jolted into action by the Hamas attack.

What underlay both the protest movement and then the civilian response to Oct. 7, some say, was a sense that maintaining comfortable private lives was no longer an option.

“What we had with the protest movement was people who had very fulfilling lives and who would not have considered touching Israeli politics – a world they saw as dirty and corrupt – suddenly moving into the public realm with a sense of urgency,” says Mr. Novik. “Now we hear people who would have never considered entering politics talking about joining parties or forming new ones.”

Ms. Wilf agrees, saying Israelis had been lulled by a period of good times, generally living well and prospering, and “forgot about those other elements that made Israel strong.”

Then on Oct. 7 “so many Israelis felt viscerally what it means not to have a state,” she adds, “and now what we see is a real sense of returning to the basics of how we rebuild our society.”

More cautious is Dr. Enoch, who says nothing he’s seen in recent months ensures a political renaissance.

“A lot of the heroics and individual actions since Oct. 7 have been unbelievable movie stuff,” he says. “But if you go to any of the frequent demonstrations there’s still zero discussion of the death and suffering Israel is inflicting in Gaza,” he adds, “so that tells me the Israeli psyche remains in a horrible place that isn’t yet ready for positive change.”

If Mr. Novik finds anything hopeful six months after Oct. 7, it’s the glimmers of a new willingness to take part in public life – including politics.

“The evidence is out there of people who now see staying away from public involvement as a luxury they cannot afford if they want their children to grow up in a normal society,” he says. “If they do take the next step to play some role and change our politics,” he adds, “it will be one positive outcome from the trauma we’ve experienced.”

Today’s news briefs

• U.S. to Israel: President Joe Biden has told Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that future U.S. support depends on new steps to protect civilians and aid workers, saying that an “immediate ceasefire is essential.” The leaders’ conversation comes as an Israeli strike killed seven workers for the World Central Kitchen.

• No delay: A judge rejected Donald Trump’s bid to delay his April 15 hush money criminal trial until the Supreme Court rules on the presidential immunity claims he raised in another of his criminal cases. Manhattan Judge Juan Merchan ruled Mr. Trump’s lawyers had myriad opportunities to raise the issue earlier.

• Civil servants: The U.S. Office of Personnel Management issued a new rule making it harder to fire thousands of federal employees, hoping to head off former President Donald Trump’s promises to remake the workforce along ideological lines if he wins the White House in November. The rule will bar career civil servants from being reclassified as at-will workers.

• NATO at 75: NATO foreign ministers meet to celebrate a milestone, having agreed to start planning for a greater role in coordinating military aid to Ukraine. “As we face a more dangerous world, the bond between Europe and North America has never been more important,” NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said.

Public office isn’t ‘mom-friendly.’ Women lawmakers are changing that.

Mothers in public office can weigh in constructively on new laws that affect women, children, and families. Some of them are trying to make government service more family-friendly in the first place.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

When Democratic lawmaker Elizabeth Bennett-Parker made the almost two-hour drive last spring to the Virginia state Capitol for a legislative session, she insisted her husband come with her – in case she went into labor. Although it was only a month until her due date, staying home wasn’t an option. Now, she’s trying to change that.

Moms in government across the country are advocating for more help like on-site day care, higher wages, and campaign funding for child care. According to a recent Pew Research Center poll, 48% of American women say family duties are a “major reason” there are fewer women than men in high political office.

Mothers like Ms. Bennett-Parker make up 18% of the U.S. population, but only 7% of those serving in Congress, and even fewer in state governments.

Liuba Grechen Shirley founded Vote Mama, a mothers-in-government advocacy group, in 2018 after she lost her New York congressional race. Since then, her organization has worked to legalize campaign funding for child care in 29 states – and saw use of those funds increase by 2,156% between 2018 and 2022.

For Kentucky representative Lindsey Burke, knowing she can pass laws that might benefit her son makes the challenges worth it. “Being a mother is the reason I’ve chosen to stay in government.”

Public office isn’t ‘mom-friendly.’ Women lawmakers are changing that.

When Democratic lawmaker Elizabeth Bennett-Parker made the almost two-hour drive last spring to the Virginia state Capitol for a legislative session, she insisted her husband come with her – in case she went into labor. Although it was only a month until her due date, staying home wasn’t an option. A positive COVID-19 test would have allowed her to participate online, but early labor wouldn’t cut it.

Now, she’s trying to change that.

“A 405-year-old institution should occasionally examine itself,” she said in a speech on the Virginia House floor, in which she proposed a commission to modernize the legislature, including expanding options for remote voting.

Women like Ms. Bennett-Parker with minor-age children make up 18% of the U.S. population but only 7% of those in Congress and an even lower share of those serving in state legislatures. By contrast, 1 in 4 members of Congress are fathers of minors. According to a Pew Research Center poll last year, nearly half of American women point to family duties as a “major reason” there are fewer women than men in high political office.

To change that dynamic, female legislators across the country are advocating for policies like on-site day care, higher wages, and the ability to use campaign funds for child care — policies they say will allow more mothers to make their voices heard in government.

“The more we talk about these issues and the things that hold women back both from running and serving, the more we start to normalize what it looks like to be a mom running and serving,” says Liuba Grechen Shirley, founder and CEO of Vote Mama, a mothers-in-government advocacy group based in New York City.

Those who support making it easier for mothers to serve in government say they bring a critical perspective to legislation on issues like pregnancy, child care, and the education system.

“Mothers of young children have been underrepresented, and so that means that important policy issues that affect so many people in the community are just not getting addressed,” says Jean Sinzdak, an associate director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University.

Moms with young children have been increasingly in the spotlight in Congress. In 2018, Democratic Rep. Katie Porter became the first single mother elected to the House of Representatives, and Democratic Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois became the first member of the Senate to give birth while in office.

This year, Republican Sen. Katie Britt of Alabama emphasized her role as a mother in her State of the Union rebuttal, and Reps. Anna Paulina Luna of Florida and Sara Jacobs of California introduced a bipartisan bill in January to allow women to vote by proxy up to six weeks after giving birth. Their bill – prompted by Ms. Luna’s personal experience – is unprecedented in Congress.

Legislative work, whether in state capitols or in Washington, can pose unique challenges for mothers. Commutes can take hours, and the daily schedule is often unpredictable. Only Alaska’s state capitol, in Juneau, provides in-house child care. And only one state, Colorado, offers lawmakers paid parental leave – largely because of the advocacy of Democratic Rep. Brittany Pettersen, a former state representative and mother of one.

In New York, a record number of mothers are now serving in the state legislature and have banded together in what they informally call the “Mom Squad.” Members collaborate on policy affecting mothers and children – and sometimes watch each other’s kids during the workday, a practice New York Rep. Jessica González-Rojas calls a “lifeline.”

In Vermont, former Rep. Emma Mulvaney-Stanak introduced a novel bill last year that would allow legislators of all genders to be reimbursed for child care.

Ms. Shirley founded Vote Mama in 2018 after she lost her New York congressional race, but became the first candidate in a federal election to win approval to put campaign funds toward child care expenses. Since then, her organization has worked with other mothers to legalize using campaign funds for child care in 29 states – and saw the use of those funds increase by 2,156% between 2018 and 2022.

These efforts are being spearheaded and largely supported by Democrats, partly because 73% of moms with minor children who serve in state governments are, in fact, Democrats. But there’s growing evidence of bipartisan support.

Forty percent of all federal funds that women spent on child care between 2018 and 2022 was used by Republicans. And conservatives like Representative Luna, who’s advocating to let new mothers vote by proxy, or Georgia state Sen. Ricky Williams, who’s supporting a bill to let parents with young kids skip to the front of voting lines, cite their own children as the reason they support parent-friendly policies.

Still, some say changes are coming too slowly.

In 2018, then-candidate Josie Raymond’s advocacy helped make Kentucky the fourth state to allow mothers like herself to use campaign funds for child care. But the Democratic state legislator says too many mothers are overburdened by high child care costs.

In Kentucky, the average annual cost of child care for 40 hours a week is $27,230. Last year, Ms. Raymond’s salary as a lawmaker – considered a part-time job – was $39,000. And that’s higher than in many states – including New Hampshire, where legislators have made $100 a year since 1889.

Paid family leave, set schedules, and on-site child care “feel so far off,” says Ms. Raymond.

Another Kentucky representative, Lindsey Burke, has been breastfeeding her infant son from her car outside the state Capitol. A lactation room was installed last year, but it’s nowhere near her office building or the House floor.

But for Ms. Burke, knowing she may be able to shape legislation that might one day benefit her son makes all the challenges worth it. “Being a mother is the reason I’ve chosen to stay in government.”

In US capital, rats thrive where civic trust is low. Here’s a fix.

In the age-old battle against rats, veterans in Washington, D.C., are reaching consensus that victory is measured not in annihilation, but in changing human behavior by building community trust and cooperation.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

Sophie Hills Staff writer

They scamper through the Rose Garden, they shut down the National Security Council Situation Room, and they have survived a federal extermination act aimed directly at them. They are rats, and they have long reigned here in the capital of the most powerful nation – right under the nose of officialdom.

The rat problem is “a sign of the erosion or decline of a public realm,” says former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, who in 1999 held what was reportedly America’s first Rat Summit.

Visits with citizen rat patrols and professionals battling rodents here suggest a growing consensus that the solution to the rat problem is in building up civic trust and cooperation. With that, they prove victory in the rat wars is possible.

Tools of battle – Kevlar seals for plumbing, poison, wise landscaping – go only so far. Key to solving rat issues in any city is to change behavior – but not that of the rats, says Gerard Brown, the district’s rat czar whose team of 17 inspectors got more than 17,000 calls last year. “Rats need three things ... food, water, and a place to live,” he says. “And most of the time, we provide that for them.”

In US capital, rats thrive where civic trust is low. Here’s a fix.

Nancy Balph talks like a national security official about battling her enemy: More eyes, more boots on the ground. If you see something, say something.

She’s tracking a cunning adversary that can penetrate fortresslike buildings. It multiplies exponentially if left unchecked. It has been the bane of humanity’s existence going back to at least the Middle Ages.

It is the rat.

But it has met its match in Ms. Balph, a senior construction project manager at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., where a pungent odor grew as students emptied out during the pandemic and the rats moved in. At first she was curious. Then she was mad, thinking, “Wow, we can’t fix this? I find that hard to believe.”

Ms. Balph walked the campus with an exterminator, city pest officials, and rat-tracking dogs. She learned to spot the burrows, the brown trails created by an oil the mammals secrete as they scuttle along – and the holes along the bottom of loading dock doors. But her real breakthrough came when she found Robert Corrigan, a rodentologist who got his start crawling through New York sewers.

“It’s not Joe Schmoe with his spray gun and traps,” says Ms. Balph, who persuaded the university to hire him. “This is someone who will help us understand what is going on.”

Last on to-do lists, first to weaken civic trust

And what is going on, say many involved in the battle, is arguably a failure of society, of democracy – a breakdown of civic trust and cooperation.

Rats “are a sign of the erosion or decline of a public realm,” says former Washington Mayor Anthony Williams, who in 1999 held what was reportedly America’s first Rat Summit.

Rats have long reigned in the capital of the most powerful nation – right under the nose of officialdom. At the U.S. Capitol, janitors and police testify – off the record – to their presence, with one claiming a bedraggled rat found on a bathroom floor came up through the plumbing. A big one scurried behind President Donald Trump during a 2020 Rose Garden appearance. Another sighting, decades before, caused the National Security Council to evacuate the Situation Room, according to a “top-secret” report obtained by The Washington Post. The newspaper also joked about rats exposing State Department divides over strategic weaponry: conventional broom and mop, or chemical agents.

The story of rats versus humans is age-old. But 300 years after the Enlightenment began, most of humanity is still battling these 1-to-2-pound whiskered creatures with poison or the brute force of Neanderthals.

Even Washington, which boasts three of the four most-educated ZIP codes in the United States and a federal government with a $6 trillion budget, faces an uphill battle. Last fall, Orkin pest control ranked it the fourth-rattiest city in America – after the much larger metropolises of Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York.

In July 1967, President Lyndon Johnson – addressing inner-city blight – sought $20 million for urban rat extermination. Though initially stymied by Congress, he got a rat control bill by year’s end. But it didn’t last.

“The federal government should, absolutely, have a national rat mitigation plan. And we don’t,” says Dr. Corrigan, noting that responsibility gets pushed to local governments, which generally aren’t strict enough about trash management. “It’s the last thing on everybody’s to-do list.”

Rats once owned this alley

The key to solving rat issues in any city is to change behavior – but not that of the rats.

“Rats need three things ... food, water, and a place to live,” says Gerard Brown, the district’s rat czar for 20 years. “And most of the time, we provide that for them.”

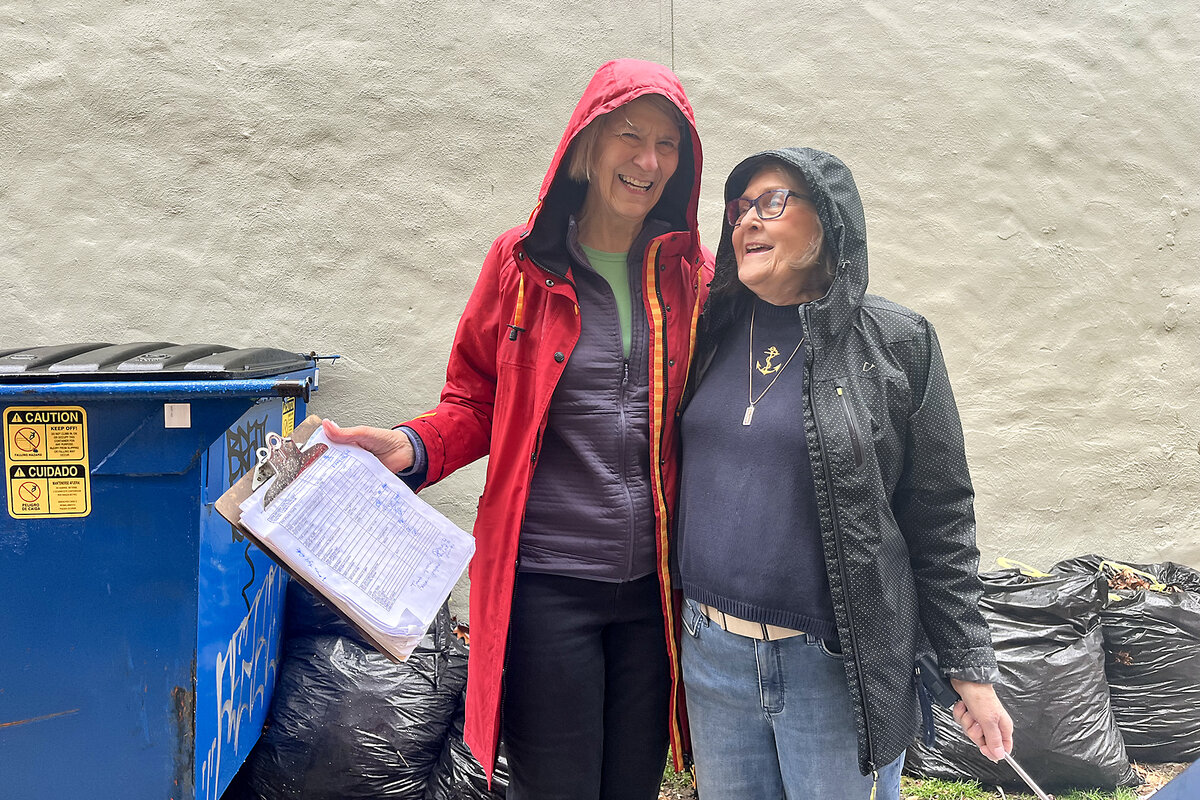

Last year, his Department of Health team of 17 inspectors got more than 17,000 calls. On a recent rainy morning, four of them walk with local residents between a row of restaurants and homes.

Seven years ago, “the rats owned this alley,” says Susan Sedgewick, a self-proclaimed “rat warrior” carrying a clipboard with a soggy stack of papers. Each line has a name, address, and space where she fills in the number of burrows found.

Flipping back to the middle of the stack, she points to improvement: “Back in April 2023, they had 12,” she says. “Now they have seven.”

Partly, that’s because she has hounded restaurants about controlling their trash.

It’s also thanks to fellow residents like Marian Connolly realizing they could do better. “I was in la-la land,” says Ms. Connolly, who would happily fill her bird feeder to attract songbirds. “It took me a long time to realize I was feeding rats.”

Jermaine Matthews, a Washington rodent control supervisor, says he loves working with the two women, both retired federal employees: “This is the greatest relationship we have, with these young ladies right here.”

The group of them has been taking these biweekly rat patrols for years, modeling the vigilance required to keep rats in check.

Then one of them spots something under the edge of a dumpster: a dead rat.

“It’s a baby,” one says, as Ms. Connolly averts her gaze.

It takes a unique character to deal with what Mike Rector of Eagle Pest Services calls “the new rage in pest control.”

“I’ve seen a lot of men very squeamish when a rat comes at them from a corner,” says Mr. Rector, who has seen a spike in rodent calls since the pandemic began.

On paper, two adult rats can produce 15,000 offspring a year, though that doesn’t actually happen, says Dr. Corrigan. A consultant to the district government for two decades, he praises Mr. Brown as “absolutely outstanding.” But he adds that while officials are important to conduct inspections and collect data, in his experience, “those community groups can do more to get rid of rats in their neighborhood than the whole city working on it.”

A failure of the golden rule

Other residents, however, would like to see the city take a more strategic, engaged approach. Mary Mason has taken the lead on the lower portion of her block in the district’s Mount Pleasant neighborhood and often calls in reinforcements from the city. They are prompt to schedule an appointment, and the inspectors sound like they know what they’re talking about. Then she gets a notice: Your request is closed.

But inevitably, she finds herself calling again. To her, it’s symptomatic of a local government that isn’t as responsive, let alone proactive, as it should be when it comes to “regular life for regular people who live here” – particularly in less well-to-do areas of the city.

Former Mayor Williams says many children are bitten by rats, and the problem is worse where residents live in substandard housing and are preoccupied with more pressing challenges than trash containment.

The Shaw neighborhood used to be like that when Brian Bakke moved in two decades ago and picked up a broom as an act of care for his neighbors. He still sweeps daily, covering several full blocks with garbage bags stuffed in his back pocket. Most days, he finds a few dead rats too, and sends “headshots” to the city to persuade them to take measures like replacing “rat plates” that keep rodents out of trash cans.

He tries to spread the gospel of rat-free living, encouraging other residents to join him in calling the city and engaging with neighborhood children, who like playing with the pretend rat skeleton in his yard. “You talk to the kids, and the kids will change the parents,” he says.

A man of faith, he says the issue is symptomatic of a failure to love one’s neighbor as oneself: “I see this as a microcosm of what is ailing our nation today.”

Not eradication, but effective management

Big neighbors like George Washington University can also make a real difference for an urban neighborhood.

When Ms. Balph got in touch with Dr. Corrigan, he came to GW, walked the campus, and produced an 80-page report. Rats, he says, need to be respected as an “incredible” mammal and scientifically managed, like wolves. “We haven’t put the science into managing rats – we’ve only put poisons into managing rats,” says the Purdue Ph.D. In many cities, he adds, codes require buildings to be rodent-proof, but the professional building industry could do more to ensure that openings under doors and around pipes and wires are properly sealed.

Following Dr. Corrigan’s recommendations, Ms. Balph led a team in “the rat battles.”

They ordered Kevlar door seals and excavated 4 feet of earth from landscaped gardens to lay rat-proof geomesh. They’ve just finished installing impenetrable Bigbelly trash cans on every street corner and even considered birth control, but Dr. Corrigan dissuaded them.

The university spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to implement his recommendations. Every dollar was worth it, says Ms. Balph, who considers the efforts 100% successful.

“Did we eradicate rats from the GW campus? No,” says Ms. Balph, who still texts Dr. Corrigan at every hour of the day and night. “We are managing them very well though.”

Points of Progress

‘Yes’ to housing, and teaching as a second career

In our progress roundup, the left and right find common ground on housing issues in the United States, and demand for a British nonprofit grows thanks to professionals who want to learn how to teach.

‘Yes’ to housing, and teaching as a second career

Activists and legislators – from the left and the right – are collaborating to alleviate housing woes

Despite a recent study finding that half of U.S. renters spend more than 30% of their income on housing, both blue and red communities struggle to overcome not-in-my-backyard sentiment decrying housing reforms. But increasingly, a previously left-of-center alliance that styles itself as YIMBY – meaning “yes in my backyard” – is finding it also has much in common with conservatives.

This year’s YIMBYtown, an annual meeting of pro-housing advocates, was held in Austin, Texas, and included conservative lawmakers and think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute.

Last year, the Republican-dominated Montana Legislature passed bills that all but eliminated single-family zoning. A bipartisan group of Arizona lawmakers passed similar changes in March. Calling these policy concerns pro-business and pro-property rights, Texas Rep. Cody Vasut said, “Some issues become a horseshoe. We have different views of government but sometimes we arrive at the same conclusion.”

Though such bipartisanship allows both sides to claim political wins and can break the stagnation on housing policy, some are wary of the contradictions of working with opponents in today’s political climate. But “the more we can find areas of agreement,” said YIMBYtown organizer Liz McGehee, “the more we can adjust to each other with less fear, and maybe that will help drive down the polarization.”

Sources: The New York Times, Bloomberg

A prison recycling program in Panama, designed by an inmate, is lowering recidivism

La Joyita, located just outside the capital, is one of Panama’s largest prisons – infamous for being overcrowded, filled with trash, and a hotbed of gang violence. Franklin Ayón, a soil scientist who was imprisoned at La Joyita in 2012 on drug trafficking charges, created a recycling system that authorities and gang leaders agreed to try, giving incarcerated people a second chance.

Through EcoSólidos, 80% to 90% of the prison’s waste is collected, separated, recycled, and sold. The group also composts food waste, using it to grow fruits and vegetables in the prison’s garden. Recidivism has declined from 65% to 45% since 2019.

Four other prisons in Panama have re-created the program, and authorities in Honduras, Paraguay, El Salvador, Peru, Colombia, and Nicaragua have shown interest. In 2016, Mr. Ayón received a presidential pardon for his work at La Joyita. His nonprofit, GeoAzul, employs previously incarcerated people who compost more than 10 metric tons of waste each day in Panama City.

Sources: The Guardian, International Committee of The Red Cross

A nonprofit that encourages teaching as a second career is drawing more interest

Every year, the British group Now Teach is helping to expand diversity and fill shortages. Teacher vacancies in England have increased 93% since 2019, and many teachers quit due to stress, low pay, and increasing workloads. In 2017, Lucy Kellaway expanded on her own journey from journalist to teacher and founded the Now Teach charity to help others changing careers.

Now Teach recruits and supports participants; 850 people working in 100 secondary schools have become teachers by being part of the network. The nonprofit is also helping to build a more diverse teaching force: About 32% of its trainees are people of color, compared with the national rate of 21%. And compared with 30% of trainees nationally, 44% of Now Teach trainees are men.

While second-career teachers often accept a significant pay cut, they say being able to use their experience to make an impact on students makes it worth it. “I have had students write to me that I have helped them realize their potential and what path to take in the future,” said Deepak Swaroop. “That is more valuable to me than money.”

Sources: Reasons to be Cheerful, The Guardian

A startup in Madagascar is enlisting large corporations to finance coral farms

Koraï was designed to appeal to companies with corporate social responsibility programs, whose reporting requirements European Union firms must fulfill to demonstrate environmental sustainability practices. When Jeimila Donty took over the family business in 2020, the company was exporting coral to aquarists. But she found a way to honor her late father’s wish of running his business more sustainably by shifting to a model of green entrepreneurship.

Though the country remains rich in biodiversity, Madagascar’s 927 square miles of coral reefs have been subject to coral bleaching, overfishing, and sedimentation from deforestation since the 1980s.

Koraï planted 1,500 coral cuttings about 17 miles from Nosy Be island last year, with a mortality rate of less than 5%, according to Ms. Donty.

Madagascan researcher Gildas Georges Boleslas Todinanahary said that the government could better support marine conservation and the people who rely on fishing the reefs for a living. But he also said that for-profits have the potential to achieve a higher impact when it comes to restoration than charities.

“I’m part of a different generation than the ones before me,” said Ms. Donty, who earned a business degree in France. “I want to use what I know to incorporate the environment into my business model.”

Source: Mongabay

An all-women crew is fighting fires in Borneo

In West Kalimantan province, the Power of Mama group is protecting villages and expanding ideas about women’s roles and influence. Many of Borneo’s peatlands have been drained of water to make way for plantations, making them highly susceptible to wildfires and rendering slash-and-burn agriculture more dangerous. Peatlands hold twice as much carbon as all of the world’s forests – and it is released when they burn.

The Power of Mama has 92 members from six villages in West Kalimantan, which neighbors a rainforest with a large orangutan population. They patrol on motorbike and by boat to spot fires early, and emphasize prevention. The group was established in 2022 by the Indonesian Nature Rehabilitation Initiation Foundation. Power of Mama also visits farmers to encourage the use of compost fertilizer and to make their land more productive. Children are also taught about land management.

Though male residents mocked the women when they began, Power of Mama is now routinely invited to village meetings. “It’s constant love and so much fun,” founder Karmele Llano Sanchez said of the women’s teamwork. “They are so eager to be seen, and to know people, and to do stuff that is not just cooking for their families.”

Sources: Mongabay, BBC

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Israel confronts its religious identity

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The conflict in Gaza has sharpened a debate within Israel about the purpose of Jewish prayer during war. Does it bring peace as much as the carrying of arms into battle? The question was sharpened this week after the country’s High Court of Justice barred state funding to ultra-Orthodox schools for students who are of the age for military conscription. The ruling gives the government 30 days to come up with a strategy for folding this large religious minority, known as Haredim, into the military.

A religious exemption from the draft for Haredim dates back to the founding of modern Israel. The ultra-Orthodox communities argue that their study, prayer, and living according to Jewish law constitute an essential defense of Jewishness and the Jewish people. “We live by the word of God, who is above everything,” says Yehuda Cohen, a young Haredi resident of Jerusalem. “Studying the Torah, especially in these days of conflict, is a way for us to fight the war.”

Some 70% of Israeli Jews support drafting Haredim. Yet in the debate over the value of prayer, the conflict is also prompting Israelis to confront the causes of war – and whether prayer can prevent it.

Israel confronts its religious identity

The conflict in Gaza has sharpened a debate within Israel about the purpose of Jewish prayer during war. Does it bring peace and security as much as the carrying of arms into battle?

The question was sharpened this week after the country’s High Court of Justice barred state funding to ultra-Orthodox schools for students who are of the age for military conscription. The ruling gives the government 30 days to come up with a strategy for folding this large religious minority, known as Haredim, into the military.

A religious exemption from the draft for Haredim dates back to the founding of modern Israel in 1948. The ultra-Orthodox communities argue that their study, prayer, and living according to Jewish law constitute an essential defense of Jewishness and the Jewish people.

“We live by the word of God, who is above everything,” Yehuda Cohen, a young Haredi resident of Jerusalem, told The Guardian. “You see, studying the Torah, especially in these days of conflict, is a way for us to fight the war.”

As Israeli society has grown increasingly discontent with the war in Gaza, the special treatment for Haredim has become a source of division. The issue renews a debate familiar to many wartime societies about finding a balance between equal sharing of national defense and a right of individuals to rely on conscience or prayer as a means of peace. Getting that balance wrong in either direction can weaken the cohesion of a nation at a point when it cannot afford to lose either.

Granting exemptions from military service too broadly can undermine a government’s aims and erode the values that bind societies, wrote Wojciech Ciszewski, a law professor at Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland, in the Oxford Journal of Law and Religion in 2021.

The war in Gaza has boosted calls for shared sacrifice among all Israelis. A poll by the Israeli Democracy Institute in March showed that 70% of Israeli Jews support drafting Haredim. Yet in the debate over the defensive value of prayer and religious practice, the conflict is also prompting Israelis to confront more deeply the different causes of war – and whether prayer can prevent it.

“Real Jews ... want to live in peace with the neighbours like we lived for hundreds of years,” wrote Rabbi Naftuli Flohr, a member of one of Jerusalem’s oldest Haredi associations, in a post on X, formerly Twitter.

All around the world, people have responded to the wars in Gaza, Ukraine, Sudan, and elsewhere with prayer. The debate in Israel over whether to draft young Haredi men has put a useful spotlight on alternative ways to end conflict and bring peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

How do we know what is real?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Paul Trowbridge

Through a better understanding of our spiritual identity, we can break free from discord, including injury.

How do we know what is real?

Peck, peck, peck: A junco was darting outside our house with tremendous energy. This small gray and white bird seemed to have great determination as he pecked relentlessly at our windows. He was apparently seeing his reflection as a competitor – a threat against which he dutifully guarded.

We might say the bird was well-meaning, but uninformed. He was taking action against an unreal competitor.

The junco’s actions alerted me to watch my own assumptions about what I see in the world. How often are our actions based on our misperceptions? How do we know what is illusion and what is real?

Christian Science helps us see beyond a limited, human view of the world and gain a larger understanding of what is real. Mary Baker Eddy, the discoverer of Christian Science, showed throughout her writings that the divine Mind, or Spirit, not the physical world, is our true source of being. She declared in “the scientific statement of being” in the Christian Science textbook, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all,” and, “Spirit is God, and man is His image and likeness. Therefore, man is not material; he is spiritual” (p. 468).

When I was 10 or 11 years old, I was quickly healed through Christian Science by these truths. I was cutting food in the kitchen with my mother, and I cut my finger. I immediately declared and accepted that idea – which I had learned in my Christian Science Sunday School class – that man is not material but spiritual. I saw myself not as a material person cutting myself, but as Spirit’s, infinite Mind’s, reflection. I felt loved and completely safe. I looked down and saw that the cut was instantly gone. My mother, who witnessed this event, rejoiced with me.

This healing was something new in my experience and gave me a hunger to know more about spiritual reality. This spiritual reality is greater than what we can perceive with the physical senses.

The Lord’s Prayer, which Christ Jesus gave us, concludes with the affirmation, “Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory, for ever” (Matthew 6:13). God owns the universe, and that universe is Godlike – spiritual, good, powerful, loving, intelligent, and glorious – and is so forever. There are no gaps in “for ever” where the opposite can take over.

This kingdom seems to be contradicted by what’s perceived through the material senses. But God’s kingdom, the power and glory of divine Love, is the only power. In reality, God’s kingdom is the only permanent place there is, and it is perceived through spiritual sense.

In the experience with my finger, I glimpsed that eternal Spirit is true, that I reflect Spirit, and that my life is therefore spiritual and eternal. As spiritual ideas of God, we have a substantial existence. An eternal idea cannot be cut, removed, or distorted. Looking back, I can see that the cut finger was like what the junco saw in the window: an unreal picture of what was going on. When I declared that I reflect divine Mind, my understanding of reality changed, and so did my experience, all in an instant. I felt blessed, at one with Love.

“Love” is one of the ways that God can be described, as well as Mind, Principle, Life, Soul, Truth, and Spirit. Divine Spirit is not trapped in a material world; God is not an anthropomorphic being sitting on a cloud dishing out good and evil. All these synonyms for God point to an eternal, omnipotent, ever-present goodness.

As we come to know God, Spirit, better, this leads us into understanding the true, spiritual identity of ourselves and everyone as expressive of God. As God’s reflection, we live in Spirit, expressing Love in harmony, perfect health, and soundness of mind.

We need not peck at illusions. Mrs. Eddy writes, “We must reverse our feeble flutterings – our efforts to find life and truth in matter – and rise above the testimony of the material senses, above the mortal to the immortal idea of God” (Science and Health, p. 262). We must challenge our human conceptions, be they little or big – reflections in windows, cut fingers, or a broken world.

An understanding of God, omniscient Mind, leads us to grander, more uplifting views, ideas, and experiences. Understanding God, we get a clearer idea of what is real.

Adapted from an article published in the June 10, 2019, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Post-quake reunion

A look ahead

I hope you enjoyed our stories today. Tomorrow, we’ll have a report by Sarah Matusek and Henry Gass from Eagle Pass, Texas, looking at the state’s use of National Guard and other state troops.