- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 14 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Amid global changes, small farms are fighting for their future

- Today’s news briefs

- Building takeovers push campus protests into volatile new phase

- Fearing an invasion of Rafah, Palestinians plan to flee. But where?

- To combat racism and antisemitism, John Eaves empowers college students

- Why Ugandan farmers gladly grow crops for chimps

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

What we can learn about change from John Eaves

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Albert Schweitzer wanted to do something. The theologian and philosopher knew how colonialism impoverished and exploited local communities, so in 1913 he founded a hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon. He would later win the Nobel Peace Prize. Asked how people could overcome injustice and suffering, he answered, “Everyone must find their own Lambaréné.”

John Eaves has found his. Our Q&A today by Ira Porter explores how Mr. Eaves felt inspired to take on -isms, the racism and antisemitism he feels as a Black Jew. The result is a small but powerful movement, and a reminder that change always starts in our own hearts.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

Amid global changes, small farms are fighting for their future

Farmers were once a cornerstone of civilization. But global economics and environmental needs are now making them fight to survive the modern world.

-

Whitney Eulich Special correspondent

-

Srishti Jaswal Special contributor

Fernando Matus Hernández grows heirloom corn in a remote mountainside town in southern Mexico. It’s difficult work, and the sun beats hard on his back as he digs shallow holes in the dry earth, dropping a grain of seed corn into each. In summer, this will be a towering row of yellow Olotillo corn.

He feels deeply connected with his ancient profession, he says. He’s also proud that this corn is central to Mexico’s culture and identity. “We have to follow the path our parents and grandparents left for us,” Mr. Matus says.

But the pressures of the modern world are hollowing out a profession as old as civilization. Cheaper imported foods, environmental regulations, and costs are squeezing small farms to the point of extinction, and farmers around the globe are fighting back, engaging in often raucous street protests.

“The project of modernity is a project without people working the land,” says Morgan Ody, general coordinator of La Via Campesina, an international small-farmers organization. But farming is “deeply rooted in our memories and in the memories of our ancestors. It’s not only an economic and social issue; it’s also very much something spiritual and emotional.”

Amid global changes, small farms are fighting for their future

Julie De Smedt tries not to picture her future too often. When she does, she has trouble imagining herself anywhere but here, planted on this stretch of fertile land that runs from her childhood home to the River Scheldt.

Her family’s cattle ranch is the last farm left on this sleepy Belgian country road. If she were a statistic, she would have left for the city. But at 21 years old, she’s made up her mind.

“I want to take over the farm,” says Ms. De Smedt, who lives doors down from her grandparents and cousins on both sides. “I don’t want to be anywhere else.”

But she knows how unlikely her dream is. Sometime soon, all her family farm’s land will be converted into a nature reserve. The European Union is pushing to restore ecosystems in the face of widespread environmental degradation, which contributes to climate change, so the state has expropriated their land.

The family is not against green policies. “There has to be nature, and there have to be people who defend nature,” says Wendy Vasseur, Ms. De Smedt’s mother, looking through the back door of a cow barn at the line of trees that marks the boundary of the future reserve.

But nobody seems to care what will become of their family and the life they have built on this land, they say. They already lost half their land to the nature reserve, and the money they received as compensation wasn’t enough to buy more. If they lose the rest, that would be it for the business.

“We are feeling really helpless right now,” Ms. De Smedt says. Still, she and her brother decided to drop everything and join a host of other farmers who drive caravans of tractors into Brussels, the capital of the EU, to fight both for their family farms and an ancient way of life.

Small-farm owners around the globe, in fact, are feeling that same sense of helplessness. From Germany and Spain to India and Canada, farmers are rising up to protest not only burdensome new environmental regulations but also the impact of corporate mega-farms and cheap food imports, which have caused their costs to rise and their profits to fall dramatically. So, many around the world have driven their tractors into capital cities, sometimes spraying manure on city streets and sidewalks. They’ve blocked major freeways, set fires in urban metro stations, and demanded changes to policies that, to them, feel like death sentences.

“What they want is a decent living,” says Morgan Ody, general coordinator of La Via Campesina, an international small-farmers organization. “What they want is respect for their work.”

It would be a mistake, she says, to see the latest wave of protests as simply right-wing backlash against the green agenda. True, some farmers oppose green policies on political grounds, but many support them. As rural areas lose population, farmers on every continent say they are being sacrificed to meet the demands of a society that no longer values the people who feed it. How long will they be able to survive in a world that has long seen fewer farmers working the land as a sign of progress?

It is no surprise, Ms. Ody says, that at a time of crisis in humanity’s relationship with the environment, farming has become a battleground.

“The project of modernity is a project without people working the land,” she says. But farming is “deeply rooted in our memories and in the memories of our ancestors. ... It’s not only an economic and social issue; it’s also very much something spiritual and emotional.”

A cow and a pig were all Ms. De Smedt’s grandfather needed to open this farm in the 1950s. As agriculture intensified and industrialized, the farm, too, grew. Today, the wooden barns the family built itself hold 250 cattle, whose meat is sold mainly to French grocery chain Carrefour.

They fatten their cows on corn and beets they grow on the land destined for the nature reserve. And they will continue for as long as they can, Ms. Vasseur says. But it is a perpetual battle to keep the farm going, and Ms. Vasseur has to work a full-time job at a nearby factory to make ends meet.

The price they can charge for their beef has not kept up with the rising costs of inputs such as fertilizer and pesticides needed to keep poisonous weeds at bay. Now, the family business has to deal with rules governing crop rotation and fallow land, policies they believe are unrealistic.

“If we had no children, it would be finished,” says Luc De Smedt, Julie’s father.

Their story has repeated itself around the world for decades, says Timothy Wise, a researcher and senior adviser at the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy, an international nonprofit that promotes sustainable food production. “Bigger farms get bigger, and smaller farms disappear. Rural communities just get hollowed out.”

Between 2005 and 2020, the EU lost nearly 40% of its farms and over 5 million farmers, most of them smallholders. At the same time, the amount of land being farmed has stayed the same.

Difficult choices

That isn’t how Lieven Nachtergale wants things to end.

As coordinator of the Sigma Plan, the project responsible for Belgium’s new nature reserve, Mr. Nachtergale does not enjoy removing farmers from their land. He does, however, think it’s necessary: Natural habitats in the densely populated region of Flanders have been badly degraded, and floods pose a growing risk. In such cases, the needs of the land, if not the planet, must take precedence.

But the real problem he sees is a model of intensified agriculture that has become so disconnected from the natural world. Fields treated with herbicides, pesticides, and heavy doses of fertilizer leave native species next to no room to thrive, he says.

The EU’s Nature Restoration Law requires countries to restore 30% of their natural ecosystems by 2030 and 90% by 2050. Mr. Nachtergale’s team is helping Flanders establish 36,000 hectares (almost 90,000 acres) of nature reserve, the equivalent of 5% of the land area being farmed.

Over the years, he has grown increasingly interested in figuring out how nature and agriculture might better work together. He is working on a pilot project that would give farmers who want to produce in a “nature-

inclusive” way 2 hectares of land (5 acres) for every hectare of their own that they contribute. The goal is to restore ecosystems while keeping family farmers on the land.

“We will need farmers in the future to do this kind of management,” he says. But he recognizes the challenge of competing with bigger industrialized farms. “If we want to change the system and give the farmers a better future, I think we should pay more for what they are producing,” he adds.

He is not the only one who sees a mismatch between the price of food in the grocery store and its real value.

Agricultural crops and livestock account for 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions – hence the push to enact long-reaching environmental policies. But in the EU and North America, farmers cannot add the costs of implementing green policies to the price of their produce without losing market share to cheaper imported food.

“You can’t do both,” says Ms. Ody of La Via Campesina. “You can’t produce at the lowest possible price and at the same time follow high environmental standards.”

What do farmers want? Fair prices.

When Tijs Boelens was a child, living some 40 kilometers (25 miles) away from the De Smedts, there were no nature reserves. To his young eyes, farmers created nature. That’s what it looked like outside his living room window, anyway. He spent long hours watching swallows play among the willow trees in which an old owl nested on his neighbor’s farm.

His own grandfather had given up farming when draft horses went out of fashion. His father became an economist. But as soon as Mr. Boelens was old enough, he got a job picking apples at a nearby orchard. Now in his 30s, Mr. Boelens runs a regenerative, organic farm on 15 hectares of mostly rented land.

Two weeks after first taking to the streets of Brussels, Mr. Boelens should be harvesting arugula in the greenhouse. Instead, he sits at his laptop typing up a speech he will give the next day at a hearing at the European Parliament. Outside, rolling hills fade into mist in the distance, rain pounding the soil in which he has invested his whole adult life.

He studies data from the European Milk Board for his presentation. Over the past decade, market prices for dairy products were lower than production costs in every year but one. His demand from politicians? Fair prices.

Mr. Boelens has calculated that income from his farm falls 22% short of what he would need to meet all costs and pay his two partners and himself a fair wage. Even selling produce to restaurants and cooperatives that deliberately support local, organic farms leaves him short.

But instead of getting answers to these problems, he has watched politicians backtrack on environmental commitments. In late March, the EU indefinitely postponed a major climate change and nature protection plan that was derailed by the latest wave of farmer protests. In an earlier concession, the EU shelved a bill to cut chemical pesticide use by half. France and Germany have backed down on plans to end subsidies for agricultural diesel fuel.

“If the only thing they can do is diminish the impact of environmental laws, then they just aren’t hearing us,” says Mr. Boelens. He laments that politicians look at agriculture primarily through an economic lens.

“Farming is your lifeline,” he says. “You don’t value fresh water by its contribution to GDP, I hope. Or clean air. You shouldn’t do so with food.”

Farmers worldwide face many of the same problems: high costs, low and volatile prices, unpredictable weather, soil erosion, and symptoms of climate change such as drought. Over half of the planet’s farmland is degraded.

Some see hope in technology to make intensive farming more sustainable. In precision agriculture, new tools can analyze soil and apply just the right amount of inputs such as fertilizer, herbicides, and water. And robots have been trained to weed organic farms.

Not everyone wants to farm, acknowledges Mr. Boelens. In most wealthy nations, fewer than 2% of the population are farmers, and they are aging. But it would be unwise to replace human hands with expensive machinery entirely, says Mr. Boelens.

“It’s not drudgery,” he says of his daily toil. “It’s the way I communicate with myself and with the earth.” He says he doesn’t farm for himself but for generations to come, “to see things today and realize they will be even more beautiful tomorrow if you take care of them.”

Culture has value, but not a price

If Mr. Boelens looks to the future, Fernando Matus Hernández – who grows heirloom corn in a remote mountainside town in southern Mexico – draws strength from the past.

It is only midmorning, but the sun beats hard on his back as he digs shallow hole after shallow hole in the dry earth, dropping a grain of seed corn into each. In summer, this will be a towering row of yellow Olotillo corn.

Historians believe that maize was first domesticated in Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago, not far from Mr. Matus’ small plot of land. The crop has since become central to the country’s culture and identity. “We have to follow the path our parents and grandparents left for us,” Mr. Matus says.

It is a tough path. The 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) opened the Mexican market to U.S. corn. Imports quadrupled in 10 years and prices fell nearly 70%, making it hard for small and subsistence corn farmers to survive in Mexico.

Hundreds of thousands of them left their fields. Mr. Matus is the only one of six siblings who still works the land full time; for him, cultivating heirloom corn is about more than feeding his family. Without it, “we’d lose our history and all of its lessons,” he says.

The economic logic of free trade, that everyone benefits by producing what they can make most efficiently, does not necessarily work when it comes to food, says Mr. Wise, the trade and agriculture expert.

“Part of the disconnect is that the global markets do not capture the value of what’s produced,” he says. “In Mexico, where corn is literally defined in the mythology as the source of human life, it is not fair to say, ... ‘Just leave your farms; just forget it.’”

That is clearly not an option for Claudia Zarate, who has been walking up and down the mile-long stony path to her plot of heirloom corn, squash, and black beans since she was a girl, 40 years ago.

The fact that so many of her compatriots choose flavorless tortillas made from mass-produced corn, she says, reflects how little they value small farmers’ “hard and endless” work. People “might not see the value in our work, but they benefit from it,” says Ms. Zarate, “because what we do is important” to keep traditions alive.

“What is Mexico without heirloom corn?” she asks rhetorically. “I hope I don’t live to find out.”

“Drowned in debt”

Nowhere have farmers protested longer and in greater numbers than in India. In 2020, tens of thousands of them launched yearlong sit-ins at the New Delhi city limits, protesting against farm reforms that the government eventually dropped.

In mid-February, thousands of farmers left their villages to march on the capital again, to push demands for broader and more generous minimum price guarantees for their crops.

We are “completely drowned in debt,” says Jagdev Singh, a protesting farmer from Punjab wearing a pink turban, his creased forehead revealing his distress.

“In one season, rain kills crops; in another season, drought kills crops,” he says. “We never get compensation from insurance companies and have to take loans to compensate.”

The Green Revolution brought high-yield seeds, irrigation, and fertilizers to India, tripling wheat production by the late 1960s. Yet Mr. Singh finds himself dependent on expensive tractors, seeds, pesticides, and generators for irrigation because of depleted groundwater.

The Indian government supports rice and wheat production by guaranteeing minimum prices. This is an expensive policy to maintain, but farmers complain – in an echo of their European counterparts – that the prices they get for their crops have risen much more slowly than the costs of their inputs.

That has left them in the lurch, they say. Over 11,000 farmers and farmworkers died by suicide in 2022, according to government data.

“It is an economic design to force the population from rural areas to migrate to urban areas to meet the demand of cheap labor for development,” says Devinder Sharma, a food policy analyst.

A farming household’s monthly income is just over $120. That’s below India’s minimum wage for unskilled labor, despite a government promise in 2016 to double farmers’ income by 2022. “We need to relook this entire development model,” adds Dr. Sharma.

Just want to be seen

That is a viewpoint shared by Juan Carlos Capilla, a Spanish farmer who grows wheat, alfalfa, barley, and oats. On a brisk spring morning, he is at the head of a string of yellow-vested farmers as they step out onto the highway outside Madrid. Holding their signs high – “Our ruin will be your hunger,” reads one – they march across three lanes and bring traffic to a halt.

As Mr. Capilla waves a red-and-gold Spanish flag, trucks passing by in the opposite direction toot their horns in support. That fills him with pride, though it is small compensation for the weight he feels on his shoulders. He and most of the farmers he knows are producing their crops at a loss stayed in business through subsidies provided by the EU as they pay off hundreds of thousands of euros of debt for farm machinery.

“Generation after generation after generation, and I’m going to be the last one,” he says of his farming lineage. “What have I done wrong to have to abandon this?”

In theory, Spanish farmers are protected by a food chain law, which is meant to ensure farmers a fair price by banning the sale of their meat, grain, milk, and vegetables for less than the cost to produce. But the law has been hard to implement, and it does not apply to imported agricultural goods, which are often cheaper than locally raised crops and animals.

“We are going broke,” says José Cáceres, a grain farmer here with his father. “I don’t want subsidies. I want my products to be worth their real value.”

He and his colleagues across Europe are concerned by the prospect of a free trade deal between the EU and the Southern Common Market, or Mercosur, which groups Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay. Opponents of the agreement, in the works for 25 years, fear it will allow Latin American nations to dump agricultural products that do not meet strict EU standards.

Mr. Cáceres wants all EU trade agreements to contain “mirror clauses” that would oblige agricultural imports to meet the same standards imposed on European farmers. He has not missed a day of protest, though the fields at home are begging to be sown and fertilized.

At 27 years old, he’s not sure what the future will hold.

“The system is kicking me out, telling me to ‘go away, we don’t want you,’” he says, watching cars and trucks form a long line down the highway.

A police officer strides over to offer a deal. His dad was a farmer, he begins by explaining. He gets it. The protesters can stay as long as they want, on one condition. They have to let traffic flow on each side of the highway every 20 minutes.

The group’s gaze turns to a sturdy, older man with weathered skin, one of this protest’s organizers. He ponders the police officer’s proposal and then nods vehemently.

They don’t want to ruin anybody’s day, he says. They just want to be seen.

This article has been amended to correct Devinder Sharma's outdated academic affiliation.

Today’s news briefs

• Officers killed in North Carolina: A shootout that killed four law enforcement officers began as officers approached a home to serve a warrant to a man with a felony conviction who was wanted for possessing a firearm, police say.

• States sue Biden administration: Nine Republican-led states file lawsuits challenging new Biden administration regulations that bar schools and colleges that receive federal funding from discriminating against students based on their gender identity.

• Israeli security units under scrutiny: The United States finds five units of Israel’s security forces responsible for gross violations of human rights, though the units are not barred from receiving U.S. military assistance.

• Trump fined by judge: Former President Donald Trump has been held in contempt of court and fined $9,000 for repeatedly violating a gag order that bars him from making public statements about witnesses, jurors, and some others connected to his New York hush money case. The judge warned that Mr. Trump could be jailed.

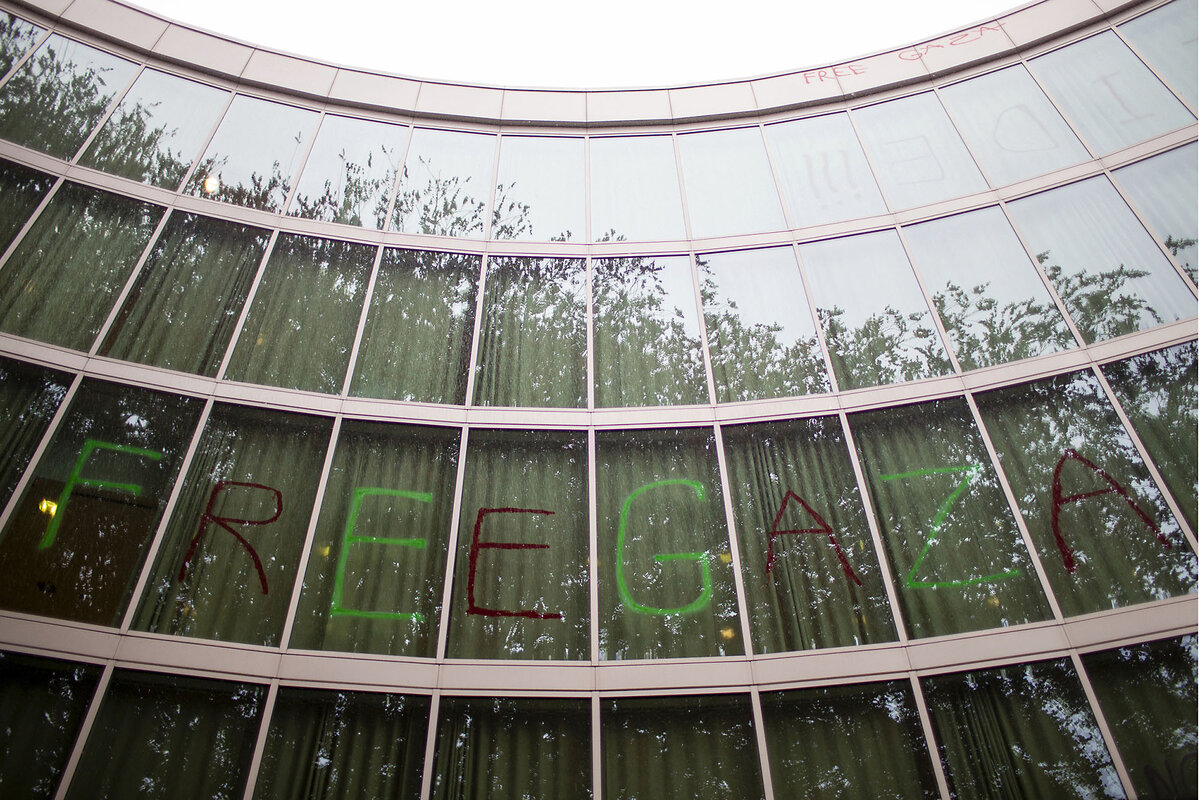

Building takeovers push campus protests into volatile new phase

For protesters, the tactic of occupying buildings at Columbia University and beyond has historical echoes. But it also creates new risks for campuses and for the protesters themselves.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

Ali Martin Staff writer

The protest movement roiling college campuses across the United States appeared to enter a more dangerous phase Tuesday, as student demonstrators who had barricaded themselves inside a hall at Columbia University were arrested overnight by police in riot gear, and protesters on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict clashed violently at the University of California, Los Angeles.

By moving from tents on a lawn to inside a building the students at Columbia sharply escalated the crisis. In parallel moves this week, protesters have also occupied buildings at some other U.S. campuses.

And while some experts say the increased pressure could still ultimately help the protesters secure some of their demands or gain more public support, in the short term it seems to have backfired, shifting more attention to their tactics than to their cause.

On Tuesday, a Columbia University spokesperson said the students involved faced expulsion for their actions. The tactic of occupying university property and refusing to leave until demands are met evokes the symbolism of past protests at Columbia and other campuses, events that have over time become celebrated as progressive landmarks by the same universities.

Building takeovers push campus protests into volatile new phase

The protest movement roiling college campuses across the United States appeared to enter a more dangerous phase Tuesday, as student demonstrators who had barricaded themselves inside a hall at Columbia University were arrested overnight by police in riot gear, and protesters on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict clashed violently at the University of California, Los Angeles.

By moving from tents on a lawn to inside a building the students at Columbia sharply escalated the crisis. In parallel moves this week, protesters have also occupied buildings at some other U.S. campuses.

And while some experts say the increased pressure could still ultimately help the protesters secure some of their demands or gain more public support, in the short term it seems to have backfired, shifting more attention to their tactics than to their cause.

On Tuesday, a Columbia University spokesperson said the students involved faced expulsion for their actions. The encampment has been cleared, and Columbia’s embattled president, Minouche Shafik, has asked New York police to remain on campus through May 17.

The tactic of occupying university property and refusing to leave until demands are met evokes the symbolism of past protests at Columbia and other campuses, events that have over time become celebrated as progressive landmarks by the same universities. At Columbia, the anti-war protests of 1968, during which five buildings were occupied for a week resulting in chaotic mass arrests, have been burnished into memory for students and faculty.

As in the 1960s, the demands and tactics at Columbia, with its “Gaza solidarity encampment” on the main lawn, inspired students at other colleges and universities, whether as coordinated actions or simply as copycats seeking to escalate.

Buildings seized on other campuses

In Portland, Oregon, between 50 and 75 pro-Palestinian students occupied a library at Portland State University late Monday. University officials have asked city police to intervene, CNN reported. At Princeton in New Jersey, a group of protesters briefly occupied a graduate-school building overnight; police later arrested 13 people, mostly students, who have been barred from campus. Students also took over a building at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque but were dispersed early Tuesday morning by state and campus police.

Earlier Tuesday morning, police retook two buildings at California State Polytechnic in Humboldt that students had occupied since last week, leading administrators to close the campus. Police arrested 35 people. One of the buildings had been renamed “Intifada Hall” by the protesters.

The White House released a statement Tuesday saying that President Joe Biden “condemns the use of the term ‘intifada,’ as he has the other tragic and dangerous hate speech displayed in recent days. President Biden respects the right to free expression, but protests must be peaceful and lawful. Forcibly taking over buildings is not peaceful – it is wrong. And hate speech and hate symbols have no place in America.”

At Columbia, protesters hung a sign reading “intifada” outside Hamilton Hall, the occupied building, which was one of the buildings seized in 1968. The building was occupied late Monday night by a breakaway group from the Gaza encampment, after an afternoon deadline passed for students to disband their camp or face disciplinary measures. The numbers inside Hamilton appeared to grow Tuesday as fewer remained at the camp. Protesters have been calling for the university to divest from Israel-related assets and to repeal the suspensions of students arrested on April 18, when over 100 were taken into custody.

Those arrests by the New York Police Department were orderly; leaders had prepared students for detention, advising them to not resist and to only speak with a lawyer present. But the occupation of a building seemed to herald a more chaotic and violent phase.

While Princeton was quick to call in police officers to end its overnight occupation, administrators at Columbia did not respond as quickly after the fallout from the April 18 arrests, which marked the first time the NYPD has been summoned to the campus since 1968. The practical challenge also appeared greater as Hamilton Hall swelled with protesters, and a phalanx of TV cameras filmed from outside the shuttered campus gates.

“Civil disobedience consists of demonstrating why a rule isn’t a good rule,” says Lara Schwartz, director of the Project on Civic Discourse at American University. She adds, “We are seeing students saying, ‘We’re going to be in places you’ve told us we shouldn’t. Because your attempts to suppress our message are wrong.’”

The role of Columbia faculty has also complicated efforts to end the occupation. Last week the university senate voted in favor of an investigation into how the leadership had responded to protests and whether it had breached due process for faculty accused of violating codes. Some faculty members have taken positions in favor of protesters, including guarding access to their camp.

How war in Gaza resonates on U.S. campuses

Protests and counterprotests have been held at Columbia since the days after Hamas attacked Israel on Oct. 7 in what was the country’s deadliest attack since its founding in 1948. Pro-Palestinian demonstrations have grown in size as Israel’s response to the attack – and to Hamas’ taking of hundreds of Israeli and foreign hostages – has decimated Gaza and killed tens of thousands of civilians, a response undergirded by U.S. military aid.

Some Jews at Columbia say they no longer feel safe on campus because of antisemitic threats and slogans from protesters, whose ranks include Jews who say their target is Israel and its leaders, not Jews as a group. A lawyer has filed a class action suit against Columbia over the displacement of Jewish students.

Although only a small minority of college students are protesting, young people ages 18 to 29 view Palestinians more positively in general. In a recent Pew Research Center poll, they were the one age group in which a higher share viewed Palestinians favorably (60%) than viewed Israelis favorably (46%).

Occupations and sit-ins have a long history on U.S. campuses. Some have been effective at forcing change on administrators. In 2001, students occupied a university hall in Harvard Yard for three weeks to protest low wages paid to campus staff, including janitors and caterers. The university eventually agreed to raise their hourly wages.

One prospect for universities is that crackdowns could expand the ranks of student protesters – not necessarily by occupying buildings but being engaged in some way.

“We ... have seen that institutions engaging in tactics where their action is to suppress student speech or punish it, or punish student groups or ban student groups, have seen an increase in students saying, ‘Well, we’re going to use our voices more. Our voices are going to get bigger,’” says Ms. Schwartz at American University.

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated to reflect news developments.

Fearing an invasion of Rafah, Palestinians plan to flee. But where?

In the cramped Gaza city of Rafah, the threat of an Israeli invasion gives the overriding sense that nowhere is safe. Even as cease-fire talks enter a crucial stage, Palestinians are scrambling to find a way out.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ghada Abdulfattah Special contributor

-

Taylor Luck Special correspondent

Arab and American envoys have voiced hopes that their diplomatic push will achieve an Israel-Hamas cease-fire. But across the southern Gaza Strip, Palestinians are bracing for the feared fallout should talks fail: an Israeli offensive against Hamas in the crowded border city of Rafah.

The city is now home to 1.4 million people, including 1 million displaced from devastated communities across the coastal enclave. Families are hurriedly packing “go bags” of emergency items in case they need to flee – even though they have precious few places to go.

Comments Tuesday by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that the Israeli military will enter Rafah “with or without a deal” only added to the fears.

“There is no place to go now, no place to hide. Everywhere is crammed with people,” says Warda Shinbary, a mother of three whose family was displaced from northern Gaza.

“I never expected Israeli tanks to roll over Tal Hawa and the Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City or in the middle of Khan Yunis,” says Zayed Shaksha, whose family in Rafah is confronted by uncertainty. “Now I totally believe that when they say they will invade Rafah, they mean it.”

Fearing an invasion of Rafah, Palestinians plan to flee. But where?

Panic is setting in across Rafah.

Even as talks seeking an Israel-Hamas cease-fire enter a crucial stage this week, hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians are scrambling to find a way out of this cramped southern Gaza border city – and finding few options.

Arab and American envoys have voiced hopes for their diplomatic push to reach a cease-fire-for-hostage-release deal. But across the southern Gaza Strip, Palestinians are bracing for the fallout should talks fail: an Israeli offensive against Hamas in Rafah.

The city on the border with Egypt is now home to 1.4 million people, including 1 million displaced from devastated communities across the coastal enclave.

Families are hurriedly packing “go bags” of emergency items in case they need to flee – even though they have precious few places to go. The Arabic hashtag #WhereDoWeGo is trending.

“There is no place to go now, no place to hide. Everywhere is crammed with people,” says Warda Shinbary, a mother of three whose family was displaced from northern Gaza.

Comments Tuesday by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu that the Israeli military will enter Rafah “with or without a deal” only added to fears that families had days, perhaps hours, to leave.

Crammed coastal refuge

In their encampment of makeshift tents in the heart of Rafah city, the days-old speculation among Zayed Shaksha, his relatives, and his neighbors was reaching fever pitch: Is an Israeli offensive imminent? How soon? Will it be a targeted operation or a full-blown invasion? Where can we go?

“I never expected Israeli tanks to roll over Tal Hawa and the Al-Shifa Hospital in Gaza City or in the middle of Khan Yunis,” says Mr. Shakhsha, a driver and father of three. “Now I totally believe that when they say they will invade Rafah, they mean it.”

Thousands are dismantling tents, grabbing whatever they can, and heading to al-Mawasi – a 14-kilometer-long, 1-kilometer-wide strip of southern Gaza coastline that is already crammed with tens of thousands of displaced Gazans in tents.

The al-Mawasi region comprises 3% of the total area of the Gaza Strip yet is considered the only potential safe area. Rafah residents and displaced people are asking relatives there to reserve a few meters of sand so that they can come; some are being turned away.

Others are returning to the adjacent city of Khan Yunis, heavily damaged by an Israeli offensive in January, even amid fears the army could hit the area again.

Unable to find space in al-Mawasi when she first left northern Gaza two months ago, Ms. Shinbary now lives in a makeshift nylon tent on a plot of land between Khan Yunis and Rafah.

Now unable to leave the area, Ms. Shinbary instead has bought some canned food and three sacks of flour to help her family sit out the worst or relocate to another part of what may become a battlefield.

“I expect to be displaced at any moment as the occupation increases its threats to invade the city,” she says.

“We are sitting in tents”

Shireen Abu Ouda was nine months pregnant when she and her child, following Israeli instructions, left Beit Hanoun in northern Gaza for the south, leaving her husband behind.

In the five times she has been displaced since, she has left behind clothes, mattresses, and cookware. Now a widow with an infant and child in Rafah, she does not have the means to pick up and move again. Many families face the same predicament.

“Where can we go when a rougher offensive comes? Where can we find safety? We are sitting in tents,” she says from her tent. “If an airstrike hits a tent, God forbid, shrapnel could kill many of us.

“Everybody is afraid. It is hard to move from one place to another, really hard. We are all tired,” she says.

To survive an offensive, she is stocking up on baby formula. “If an [Israeli] invasion happens, I will be cut off,” she says.

Hanaa Abu Tima, an UNRWA teacher and mother of six who was displaced from her home in Khan Yunis, decided to return to the rubble that was once her home.

“Everything is in ruins. My house is destroyed. I can barely recognize the city,” she says from Khan Yunis.

Meanwhile, Osama Jaber, a civil engineer and Rafah resident, lined up large and small bags at his home.

He checked the contents – summer clothes, shoes, slippers, hygiene products, canned food, multiple tents – all to cover the basic needs of his family of eight and two parents. He had been preparing for two months.

“We learned from the experiences of the displaced people who came to Rafah. They left their homes without belongings, believing the war would not last long, and faced severe shortages,” he says.

His family was preparing to evacuate to the al-Mawasi coastal region, where relatives own land and have reserved a plot.

“We did not want to prepare ourselves at the last second,” he says.

Like many in Gaza, Mr. Jaber, who is also an aid worker, worries that an offensive in Rafah, which the Netanyahu government says is necessary to defeat Hamas, will cut the limited relief entering the enclave, rendering it both unlivable and cut off from the world.

“The Rafah border crossing is crucial for the entry of aid and goods. It is the only route for people to travel through,” he says.

“The Israeli occupation’s objective is to destroy infrastructure and health care to make us desperate. They have already done this in the north and in Khan Yunis; now they will do the same in Rafah,” he says.

The Egypt option

For Gaza residents, the only option to leave the strip is through Egypt – and it comes at a steep price.

There are currently two ways to get on the daily list published by Egyptian authorities to leave through the Rafah crossing. One is on medical grounds, for which there is a waiting list of thousands seeking treatment abroad.

The faster route is by paying Egyptian company Hala Consulting and Tourism Services, a broker that reportedly has links to the Egyptian government and security services.

Hala charges $5,000 per adult and $2,500 per child to exit through Rafah – sums that are out of reach for the vast majority of families.

Mr. Jaber’s family paid the $5,000 fee in advance for his brother to travel to Egypt to continue university, and are anxiously awaiting his name to be listed.

“I am worried that my brother” won’t make the list before an offensive, he says.

“I wish we could leave through Egypt,” says Mr. Shaksha, the driver, holding his infant daughter on his lap, “but who can pay the expensive fees?”

Q&A

To combat racism and antisemitism, John Eaves empowers college students

Before the Israel-Hamas war, an Atlanta college instructor and former politician, who is Black and Jewish, saw an opportunity to bring students from both those groups together. His approach offers a timely model for civil discourse on campus.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Years before Hamas fighters stormed Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, John Eaves saw a rise in antisemitism in the United States. He saw racism against American Black people, too. As a member of both the Black and Jewish communities, he couldn’t turn his eyes and ears away from what affected him most and troubled his spirit.

So the former chairman of the Fulton County commission in Georgia, and current senior instructor at Spelman College in Atlanta, thought of a way to fix the problem.

In 2021, he started Black and Jewish Leaders of Tomorrow because the once-strong relationship between the two groups, particularly solid during the Civil Rights Movement era, was eroding. College students across the country who identify either as he does, as members of both groups, or as one or the other come together to learn, ask questions, and consider ideas to combat the tide or racism and antisemitism.

“Both of us fight the same -isms. Blacks deal with anti-Black racism and Jews deal with antisemitism, and the antisemitic person and the racist are usually the same person or they’re cousins of each other,” says Dr. Eaves.

To combat racism and antisemitism, John Eaves empowers college students

Years before Hamas fighters stormed Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, killing hundreds of civilians, John Eaves saw a rise in antisemitism in the United States. He saw racism against American Black people, too. As a member of both the Black and Jewish communities, he couldn’t turn his eyes and ears away from what affected him most and troubled his spirit.

So the former chairman of the Fulton County commission in Georgia, and current senior instructor at Spelman College in Atlanta, thought of a way to fix the problem.

In 2021, he started Black and Jewish Leaders of Tomorrow because the once-strong relationship between the two groups, particularly solid during the Civil Rights Movement era, was eroding. College students across the country who identify either as he does, as members of both groups, or as one or the other come together to learn, ask questions, and consider ideas to combat the tide or racism and antisemitism.

“It checked a lot of boxes of what I believe in as a Jewish student but also someone who’s done a lot of political organizing and someone who’s interested in policy work,” says Emma Friese, a student at Emory University, who joined two years ago. She says she jumped at the chance to participate because she thought it was a cool way to meet new people.

The group’s Unity Dinner at a synagogue in Atlanta in late March was attended by 70 people, about 40 of them students. That initiative will expand in the fall, as students from predominantly white institutions visit 20 historically Black colleges and universities across the U.S. In early April, student leaders and activists from colleges in Georgia gathered for a three-day leadership conference and worked on action plans for combating racism and antisemitism on their respective campuses.

“Both of us fight the same -isms. Blacks deal with anti-Black racism and Jews deal with antisemitism, and the antisemitic person and the racist are usually the same person or they’re cousins of each other,” says Dr. Eaves.

He recently spoke with the Monitor by phone. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Why did you start Black and Jewish Leaders of Tomorrow?

I’m a former politician here in Atlanta, but also Black and Jewish, and have noted, based on my local work, activism, leadership, that Black and Jewish audiences often are concerned about very similar things from a social justice standpoint. But these audiences don’t necessarily work hand in glove with each other.

I was asked to submit a grant by the Jewish Federation of Greater Atlanta to support some new initiative, so I came up with the idea of Black and Jewish Leaders of Tomorrow. We’ve been working for the past two years in Atlanta, in terms of bringing college students who are Black and Jewish, or Black or Jewish, together, and to address issues of antisemitism and racism on the college campuses. We’ve been kind of doing this under the radar screen for the past two years and all of a sudden, especially after Oct. 7, the dots began to be connected.

How has the current crisis in the world influenced conversations or gatherings?

Oct. 7 has ramped up the sense of urgency, and this urgency is, there’s a rise of antisemitism. So it’s urgent that there are deliberate attempts like this to bring people together as opposed to this divisive climate that’s out there. It really has just made this initiative more dire in terms of, we just need to do it. ... [A] lot of Jews are not happy about the war, and unfortunately, there sort of is this feeling that all Jews are supportive of the war and insensitive towards the casualties that are occurring. And that’s not true.

How do you bridge the gap between Blacks and Jews?

There’s a history of alliances between Blacks and Jews. So we’re trying to rekindle that now. It may not necessarily be in the same form as in the past, but [it’s] something, and that’s really the focus. The war between Israel and Hamas has become just sort of this uninvited challenge that we’ve got to deal with, but it really has very little to do with what we’re trying to deal with. The relationship has not been a “Kumbaya” type of thing. It’s had challenges. The motivation is rekindling the historical relationship – and to do it between HBCUs and Jewish students who attend predominantly white institutions.

Why was it important to engage college students in this initiative?

College campuses are the training grounds for the future leaders of our society. Relationships that are established in college, whether it’s social or political, whatever kind of relationship, many times those relationships are maintained later on in life. The positive thing is, these are emerging leaders of society. You catch them at this point in their life and you educate them, you sensitize them and you train them. They can do some good things later on as leaders in our society. That’s the first thing. ... At the same time, many of these college campuses also are the incubators of antisemitism, and you just have to both educate and inspire people to want to do something good.

What’s your biggest hope for the people who participate?

There are several hopes. Number one, Black and Jewish college students realize that we’re more alike than different. Yeah, we may have a different skin color in some cases, because there are Blacks that are also Jews. We probably have different religious practices and beliefs. Yes there are some cultural things that may differ between us, but we also discover that we’ve got a lot in common.

Number two, we have to identify the -isms out there. How can we train students to deal with it themselves on college campuses? Not in a confrontational way, but in a resolution-based way – how to recognize and deal with anti-Black racism. How do you recognize antisemitism and once you recognize it, see it, what do you do about it? How do you resolve it? How do you address it? So we provide leadership development on how to address issues of -isms on college campuses.

And, then, number three, life beyond or after college. What can you do, whether it’s getting involved in the political process and you know, supporting legislation that deals with hate, or antisemitism or racism? What can you do as an advocate or an activist? What can you do maybe as a future elected official to really effect change?

In Pictures

Why Ugandan farmers gladly grow crops for chimps

Clashes between humans and wildlife are as old as agriculture. In Uganda, farmers are ensuring a peaceful coexistence with chimpanzees by planting crops just for them.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kang-Chun Cheng Contributor

Farmer Samuel Isingoma has planted 20 jackfruit trees on his 17-acre plot in the western Ugandan village of Kasongoire. The trees’ bounty is solely for chimpanzees.

“Since I support and give fruit to the chimps, they don’t disturb anything else,” Mr. Isingoma says.

With encouragement from the Jane Goodall Institute, Ugandan farmers are playing an important role in lessening the tensions between people and chimps as communities encroach on the animals’ habitat. Uganda is East Africa’s largest sugar cane producer and has one of the fastest-growing populations on the continent. The need to make space for homes and farms is reducing the forest cover that helps sustain chimpanzees.

James Byamukama, an executive director at the Jane Goodall Institute, says it’s critical to have discussions within communities rather than try to impose solutions. Community monitors from the institute’s Uganda chapter have recommended that farmers plant crops that aren’t so palatable to wildlife. Mr. Isingoma is taking the institute’s advice one step further by giving his fruit over to hungry chimps.

As a result, the farmer says, “I feel there isn’t much of a human-wildlife conflict.”

Why Ugandan farmers gladly grow crops for chimps

From the shade of a banana tree, Samuel Isingoma explains why he is sacrificing his precious jackfruit to chimpanzees.

“Since I support and give fruit to the chimps, they don’t disturb anything else,” says Mr. Isingoma, who has planted 20 jackfruit trees on his 17-acre plot in the western Ugandan village of Kasongoire. The trees’ bounty is solely for the primates.

With encouragement from the Jane Goodall Institute, a global conservation organization, Ugandan farmers are playing an important role in lessening the tensions between people and chimps as communities encroach on the animals’ habitat.

Uganda is East Africa’s largest sugar cane producer and has one of the fastest-growing populations on the continent. The need to make space for homes and farms is reducing the forest cover that helps sustain chimpanzees.

James Byamukama, an executive director at the Jane Goodall Institute, says it’s critical to have discussions within communities rather than try to impose solutions. Community monitors from the institute’s Uganda chapter have recommended that farmers plant crops that aren’t so palatable to wildlife. So about eight years ago, Mr. Isingoma started planting coffee beans, leaving behind the maize he used to cultivate.

Now he is taking the institute’s advice one step further by giving his fruit over to hungry chimps.

As a result, Mr. Isingoma says, “I feel there isn’t much of a human-wildlife conflict.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Neighborly nudge to rehabilitate Haiti

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

In one of the world’s most violent crises – which is considered by the United States to be as important as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – a solution may have started last Thursday.

Haiti’s prime minister, forced into exile by the nation’s powerful gangs, handed over authority to an inclusive group of prominent political leaders to pick a new prime minister and prepare for elections in 2026. “The situation calls us to rise above ourselves,” said interim Prime Minister Michel Patrick Boisvert during a swearing-in ceremony in the besieged capital, Port-au-Prince.

The new nine-person transitional council, however, wasn’t the only act of inclusion. In March, Haiti’s neighbors in the Caribbean decided to act in a neighborly way. The 15-state Caribbean Community saw the power vacuum in Haiti and gathered in Jamaica to help form the transitional council. Its support in putting together a Haitian-led solution is a good example of how much the world has come to rely on regional groupings of nations – in Africa, Southeast Asia, Europe, and elsewhere – to nudge a troubled neighbor toward peace or democracy.

Neighborly nudge to rehabilitate Haiti

In one of the world’s most violent crises – which is considered by the United States to be as important as the wars in Gaza and Ukraine – a solution may have started last Thursday.

Haiti’s prime minister, forced into exile by the nation’s powerful gangs, handed over authority to an inclusive group of prominent political leaders to pick a new prime minister and prepare for elections in 2026. Haiti has not held an election for eight years.

“The situation calls us to rise above ourselves,” said interim Prime Minister Michel Patrick Boisvert during a swearing-in ceremony in the besieged capital, Port-au-Prince.

The new nine-person transitional council, however, wasn’t the only act of inclusion.

In March, Haiti’s neighbors in the Caribbean decided to act in a neighborly way, even if only to prevent the migration of Haitian refugees at their shores. The 15-state Caribbean Community saw the power vacuum in Haiti and gathered in Jamaica to help form the transitional council.

Its support in putting together a Haitian-led solution is a good example of how much the world has come to rely on regional groupings of nations – in Africa, Southeast Asia, Europe, and elsewhere – to nudge a troubled neighbor toward peace or democracy.

“At times of deep geopolitical division, it is even more important that regional organisations play an active role,” said James Kariuki, the United Kingdom’s deputy representative to the United Nations.

The Caribbean Community’s support of an interim government in Haiti has already led to a renewal of Kenya’s offer to lead a multinational force of as many as 2,500 officers to quell the violence in Haiti, relying on a recent resolution by the U.N. Security Council.

Such outside support, of course, depends on Haitians themselves finally acting to save their country. “Facing this unprecedented crisis,” said Régine Abraham, a member of the new Haitian council, “the entire population has recognized the urgent need of a firm hand to take us out of this spiral of despair and destruction.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

No impasse in Mind

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Michelle Boccanfuso Nanouche

When we’re feeling just plain stuck, understanding that God is the one infinite divine Mind helps us break free.

No impasse in Mind

Among one’s first lessons in driving school is to lift the eyes from the end of the hood of the car in order to have a broader perspective of the road. The drive is then smoother and steadier, because the objects you encounter along the way no longer appear as scary, looming obstacles.

In the Bible, lifting one’s eyes often signifies seeking God and a higher, divine view of present good. Christ Jesus explained, “Say not ye, There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest? behold, I say unto you, Lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest” (John 4:35). God’s goodness is present and perpetual.

Once, when caught in a legal muddle, I found that the longer it went on, the more tempting it was to focus on what wasn’t going right. Then the case came to a complete impasse. During a long trip away, I took a break from the problem in order to nurture my understanding of God as the only true Mind – the infinite source of all good and right ideas.

I saw that in this Mind’s unlimited and perfect view, nothing and no one is ever actually stuck. Mind’s good ideas flow in a continual stream of unrestricted good. Mind knows only good and reveals good throughout its creation, which is entirely spiritual. I saw that my life, and everyone’s, expresses the flow of Mind’s intelligence, which knows no delays or stopping. As the spiritual manifestation of perfect Mind, each of us is capable of expressing intelligence as well as humility, selflessness, freedom from fear, and grace.

Upon returning from this trip, I no longer saw the others in the case as stubborn, self-interested, limited. Looking from Mind’s perspective, I saw each one’s inherent spirituality and receptivity to good. I knew that the answer to the impasse had to be right at hand.

And so it was. Within a week, the legal issue completely and happily resolved. Everyone involved in the case acknowledged that the journey to the simple and just solution had blessed us along the way.

Even in the stickiest of stuck places, the perfect solution is already at hand. We simply have to “lift up [our] eyes” – our thought – by seeking out Mind’s perspective to discover the perfect harvest of good right in front of us.

The Bible tells of a man named Balaam, who was asked by a king to come with him and his men and to “curse” the children of Israel (see Numbers 22-24). Although Balaam sought God’s guidance, he disobeyed God’s instructions and went with the men.

Even the best intentions can be derailed if personal will or desire is allowed to get in the way. Listening in prayer for what Mind sees and says – and then being obedient – broadens vision, purifies motives, improves character, and breaks through logjams.

Balaam’s journey came to an abrupt halt when his donkey suddenly bolted into a field. Balaam reacted with anger. The donkey was insubordinate two more times, and Balaam continued to lash out.

Genuinely seeking and following Mind’s lead never results in anger or exasperation, which would keep us from discerning the perpetual unfolding of good. When we lift our focus above fear, reaction, and condemnation and turn to perfect Mind, we can expect to find a blessing, and a way forward.

That’s what happened with Balaam. It turns out the donkey wasn’t being stubborn. It simply saw what Balaam, so intent on pursuing his way, had missed. In the middle of the road stood an angel.

Christian Science has helped me understand that in the Bible, angels often represent inspired ideas from God. When Balaam finally perceived the angel’s presence, he bowed his head before it and fell face down on the ground. Humbled, Balaam was finally obedient to Mind’s instruction that “only the word that I shall speak unto thee, that thou shalt speak.” Balaam and his donkey proceeded, and we find out that God’s will was that Balaam bless the Israelites, not curse them – and this is exactly what he did.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, wrote, “Mind is the source of all movement, and there is no inertia to retard or check its perpetual and harmonious action” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 283). Mind’s angels, the right ideas of God’s goodness, accompany us on the path. Turning to perfect Mind to guide us, we can find the blessing of infinite good that Mind, God, has placed right before our eyes.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Nov. 16, 2020, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Time for lunch

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. We invite you to check back on our website Wednesday morning for an early take on the armed standoff that killed four police officers in Charlotte, North Carolina. Staff writer Patrik Jonsson will look at the growing concern in police ranks about increasingly permissive gun laws. The story will also appear in Wednesday’s Daily.