- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Supreme Court sets limit on Second Amendment rights

- Today’s news briefs

- How Lebanese escape the Hezbollah-Israel fight, a war beyond their control

- Gangs have taken over Haiti. Schools must educate anyway.

- It’s much bigger than Caitlin Clark: Our writer tallies women’s recent gains

- In summertime, picking buckets of berries (with bears)

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A gun rights ruling, and lessons in Haiti

The Supreme Court is ending its term with a flurry of consequential decisions. Our lead story offers insight on United States v. Rahimi, a Second Amendment gun rights challenge that the justices ruled on today. You can find updates on other cases in our news briefs.

And don’t miss our report from Haiti. It echoes a phenomenon you find in many areas torn by conflict: a persistent commitment to educating the rising generation, no matter what. Even amid gang violence, street fighting, and displacement, Collège Florian Ganthier is doing everything it can to connect young people with books and lessons that will point the way to a brighter future.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Supreme Court sets limit on Second Amendment rights

The 21st century has seen a steady expansion of U.S. gun rights. On Friday, the Supreme Court walked back a controversial ruling from two years ago that had confounded lower courts.

-

Patrik Jonsson Staff writer

In an 8-1 decision Friday, the Supreme Court set the outer bounds on the constitutional right to bear firearms after decades of expansion.

The ruling that domestic abusers can temporarily be prohibited from owning guns – also known as 'red flag' laws – walked back a ruling from two years earlier that had decreed a “history and tradition” test for gun safety laws.

Recent precedents “were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts.

“The reach of the Second Amendment is not limited only to those arms that were in existence at the Founding,” he added. “By that same logic, the Second Amendment permits more than just regulations identical to those existing in 1791.”

With this ruling, the court loosened a history-and-tradition test set two years ago to “build in more wiggle room. That will be a welcome bit of guidance for litigants,” says Eric Ruben, a professor at Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law and a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

And the fact that eight justices signed on to the majority opinion, he adds, suggests “that in so many ways, the other justices are wresting the Second Amendment from Justice [Clarence] Thomas.”

Supreme Court sets limit on Second Amendment rights

In a near-unanimous ruling Friday, the U.S. Supreme Court set the outer bounds on the constitutional right to bear firearms that it has been expanding for almost two decades.

As in other recent gun rights cases, the decision grappled with the Second Amendment and its implications for modern public safety. At issue, in particular, is the safety of people who are or were in abusive relationships.

The case challenged a federal law prohibiting an individual subject to a domestic violence restraining order from possessing a firearm. Also known as red flag laws, these have been passed in 21 states and the District of Columbia. The plaintiff, Zackey Rahimi, claimed that the law is unconstitutional, citing a Supreme Court ruling two years ago that gun laws must be consistent with America’s history and tradition of firearm regulation.

In an 8-1 decision – albeit one in which six justices wrote four separate opinions – the Supreme Court disagreed.

Recent precedents “were not meant to suggest a law trapped in amber,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in the majority opinion.

“The reach of the Second Amendment is not limited only to those arms that were in existence at the Founding,” he added. “By that same logic, the Second Amendment permits more than just regulations identical to those existing in 1791.”

While even some gun rights supporters had misgivings about the case, the ruling surprised court watchers who have witnessed the court steadily expand gun rights. Despite the ruling Friday, more challenges over the scope of one of the country’s most polarizing constitutional protections are in the pipeline.

The 21st century has so far seen the expansion of gun rights. In District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008, the court held for the first time that the Second Amendment protected the right to keep a gun in the home. In New York State Rifle Association v. Bruen in 2022 – the case cited by Mr. Rahimi – the court held that the Constitution protects the right to carry a gun in public, which also created the “history and tradition” test. Both decisions broke along the court’s ideological lines. And just last week, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote an opinion that struck down a ban on bump stocks, or semiautomatic weapon enhancers, adopted during the Trump administration.

The 2022 Bruen decision offered little guidance to lower-court judges on how to apply the history-and-tradition test, and the past two years have been replete with divergent court rulings in constitutional challenges to gun regulations. With its ruling Friday, the Supreme Court has begun to reconcile the new judicial focus on early U.S. history with the realities of modern-day America.

Friday’s ruling was a welcome clarification of Bruen, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in a concurrence joined by Justice Elena Kagan. But the justices “remain troubled by Bruen’s myopic focus on history and tradition, which fails to give full consideration to the real and present stakes of the problem facing our society today.”

A ruling that is “transferable to the present day”

Mr. Rahimi is not the champion most gun rights supporters would have chosen for the next big Second Amendment case.

Indeed, Chief Justice Roberts began the 103 pages of opinions with a graphic detailing of his criminal history, including violation of a restraining order against his girlfriend, a separate aggravated assault charge, and alleged involvement in five other shootings across the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Those facts help explain why the decision was nearly unanimous, but also why it is relatively narrow.

“It was about a specific person, which is in the heartland of what’s permissible under historical principles,” says Andrew Willinger, executive director of the Center for Firearms Law at Duke University in North Carolina.

The analysis in Friday’s decision boiled down to the question of whether a gun regulation needs to simply be analogous to a founding-era regulation, or whether the modern regulation needs a clear historical “twin.” Eight justices agreed that the former is satisfactory.

In a solo dissent, Justice Thomas – who wrote the Bruen decision – disagreed. Because neither the government nor the majority “identifies a single historical regulation with a comparable burden and justification as” the federal law, he wrote, “I would conclude that the statute is inconsistent with the Second Amendment.”

In a separate concurrence, Justices Sotomayor and Kagan underscored why they supported Chief Justice Roberts’ interpretation. The majority opinion “permits a historical inquiry calibrated to reveal something useful and transferable to the present day,” they wrote.

The dissent, meanwhile, “would make the historical inquiry so exacting as to be useless,” they added.

The debate between the justices – visible throughout the lengthy opinion – is enlightening, legal experts say. That’s both for lower-court takes in applying Bruen’s history-and-tradition test and for the future of the high court’s Second Amendment jurisprudence.

The court “loosened the Bruen analysis to build in more wiggle room. That will be a welcome bit of guidance for litigants,” says Eric Ruben, a professor at Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law and a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice.

The fact that eight justices signed on to the majority opinion, he adds, suggests “that in so many ways, the other justices are wresting the Second Amendment from Justice Thomas.”

What does this mean for survivors of domestic abuse?

In addition to clarifying the Bruen test, the case also has profound implications for Americans in domestic violence situations.

The presence of a firearm makes it five times more likely that a person will be killed by their abuser, according to a 2023 study. One 2018 study across 49 states found that court-ordered seizures of firearms reduced intimate partner homicides by 13%.

Nor are the threats limited to intimate partners, says Jennifer Becker, a former New York City prosecutor who specialized in domestic violence cases.

Survivors report that abusive partners threaten suicide or to hurt other people in the community. There is a well-researched connection between domestic violence and mass shootings. Federal law, in essence, says, “Let’s just remove the firearms that elevate the risk so much,” says Ms. Becker, now the director of the National Center on Gun Violence in Relationships, part of the Battered Women’s Justice Project in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“We should all as a community have an interest in removing this risk of fatality. We should all care about laws that acknowledge that domestic violence isn’t a private matter,” she adds.

Gun safety advocates are not alone in wanting this. Nearly 8 in 10 gun owners support prohibiting gun possession by people subject to a domestic violence restraining order, according to a 2022 study by Tufts University funded by 97Percent, an advocacy group that promotes responsible gun ownership and enhances public safety.

Grass Roots North Carolina was one of several gun groups that signed amicus briefs supporting Mr. Rahimi – but not without a lot of internal debate about the nature of the case, the defendant’s character, and the implications if Mr. Rahimi succeeded.

“Bad cases make bad laws,” says Paul Valone, president of Grass Roots North Carolina.

But domestic violence protection orders are “a vulnerable area for gun rights,” says Mr. Valone, an airline pilot. “It is one of the most routine methods by which gun owners are deprived of their weapons – which can include collections worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Gun groups have a broader concern that Second Amendment rights are more fungible than others. The ruling Friday suggests to Mr. Valone that courts may again treat the Second Amendment as, quoting Justice Thomas, “a second-class right.”

The decision was “exactly what I expected,” Mr. Valone adds. “Thanks to the fact that they used the flawed defendant to bring the case to the Supreme Court, people who’ve committed no crimes will now be deprived of their civil rights.”

But the narrowness of the majority opinion, and the presence of four separate concurring opinions, suggest that the future of Second Amendment jurisprudence is entering a murky new era.

A challenge to an Illinois law regulating assault weapons and high-capacity magazines is now pending before the Supreme Court. Challenges to laws disarming drug users and nonviolent offenders are also likely to reach the justices. In all these cases, they will have to further clarify the Bruen test. It’s far from clear how the court will rule.

In separate, solo concurrences, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh wrote long defenses of the high court’s originalist, history-focused approach in Bruen. But Justice Amy Coney Barrett, for the second time in two weeks, took issue with the brand of originalism favored by some of her colleagues.

“As I have explained elsewhere, evidence of ‘tradition’ unmoored from original meaning is not binding law,” she wrote. “Scattered cases or regulations pulled from history may have little bearing on the meaning of the text” of the law. And “imposing a test that demands overly specific [historic] analogues has serious problems.”

With its ruling Friday, “The court settles on just the right level of generality,” she concluded. “Harder level-of-generality problems can await another day.”

Today’s news briefs

• Water dispute: The U.S. Supreme Court has rejected a settlement over the management of the Rio Grande. The 5-4 decision rebuffs an agreement recommended by a federal judge over how New Mexico, Texas, and Colorado must share the water.

• Foreign income tax: The U.S. Supreme Court, in a 7-2 ruling, preserved a tax on Americans who have invested in certain foreign corporations as constitutionally sound.

• Columbia University: Dozens of pro-Palestinian student protesters arrested in April after occupying a campus building had all criminal charges dropped.

• Ukraine: Rolling blackouts have grown as Russia has intensified strikes targeting energy infrastructure, raising concerns about meeting national demand when the cold season returns.

• Armenia recognizes Palestinian state: Israel summoned Armenia’s ambassador for what the Israeli Foreign Ministry described as a “severe reprimand.” Dozens of countries have taken this step, though none of the major Western powers has done so.

How Lebanese escape the Hezbollah-Israel fight, a war beyond their control

Nonbelligerents in war often pay a very high price in the violent disruption of their lives. In Lebanon, the children, perhaps, can be entertained and distracted in the moment, but adults are all too aware of the value of what has been lost.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

When intensified fighting erupted last October between Hezbollah and Israel along Lebanon’s southern border, many expected a scenario similar to that of 2006, when the last major Hezbollah-Israel battle destroyed much of southern Lebanon, but also ended in 33 days.

Now, more than eight months after it began, the low-level war has displaced some 90,000 Lebanese civilians from the border region and left 100 dead. Civilians are traumatized, with no end to the conflict in sight.

One farmer who fled to Beirut with his wife, days before his house was destroyed in an Israeli strike, is so despondent that he says he is “willing to go back now, put a tent on the rubble of my house, and stay.”

But for some fortunate children, the trauma of displacement is lifted by a theatre and arts program in the coastal city of Tyre run by the Tiro Association for Arts, founded a decade ago by Kassem Istanbouli.

The program allows the children to “use their voices and their bodies, to feel joy and make them laugh,” Mr. Istanbouli says. The children, he says, “dance from the beginning to the end. They have energy. They need to get this energy out.”

How Lebanese escape the Hezbollah-Israel fight, a war beyond their control

Displaced by war and traumatized by lives turned upside down, the Lebanese schoolchildren jump for joy, scream, and run with abandon when their bus arrives.

It’s a dilapidated American school bus, covered in graffiti, but it’s their ticket to an afternoon of escape.

The children race to be the first on the bus for the ride from their temporary shelter in a school to a theater renovated by the Tiro Association for Arts. There, they will participate in games on the stage and art activities that could not feel farther from south Lebanon’s front lines – which is precisely the point.

As the children sing and dance, with music blaring from the bus speakers, they are clearly grateful for this excuse to leave behind the dangers and tensions of the escalating conflict between the Iran-backed Shiite Hezbollah militia and Israel.

Over the last eight months, the low-level war has displaced some 90,000 Lebanese from the border and left 100 civilians dead.

“Bombing chased us all the way,” says a mother, who gives the name Farah, about her family’s escape to the coastal city of Tyre from their border village of Beit Lif when the fighting erupted last October. Wearing a white headscarf with sunglasses perched on top, she rides the bus with her five children, who are bursting with excitement for the theater fun that they know awaits them.

While these children enjoy a brief respite, their moment of happiness is but one bright point along the wide spectrum of challenging and often debilitating experiences for the tens of thousands of Lebanese caught in this war, which began when Hezbollah launched attacks against Israel in solidarity with the Palestinian Hamas.

The civilians are traumatized – some, they say, to the point of contemplating suicide – by the violent disruption of their lives by events beyond their control, with no end to the conflict in sight.

“Sometimes air strikes happen, and the kids hear it here and start screaming – they developed a phobia from the bombing,” Farah says. “This [arts experience] makes them forget the war, and keeps their minds busy with something else.”

Arriving at the theater, the children clamber off the bus – a brightly painted but rusting school bus built in the United States in 1977. The Tiro Association, which calls it the “Peace Art Bus,” has launched a GoFundMe campaign to pay for an upgrade.

Some children go upstairs to draw and paint in rooms hung with old movie posters and antique metal film reels. Other children pass down the aisles of plush velvet seats in the auditorium and climb onto the stage, where Tiro Association executive director Kassem Istanbouli – with his voluminous hair and irresistible energy – leads a series of acting and role-play exercises under the stage lights.

“Culture is a way of resistance,” says Mr. Istanbouli, who founded the association in 2014 to restore old theaters and turn them into arts centers. “When you open the space during a conflict, it is resistance to be alive, to say, ‘We are here,’ to say, ‘We need to complete life’ – to give joy to the children.”

“They have many dreams,” he says of the 300 children from underprivileged families that the Tiro Association now supports with art and theater.

“What is important now is to take all the pressure out,” says Mr. Istanbouli. “Imagine you lose your house; you are sitting in [shelter] schools all this time. You think you will go back in one week, and then you are eight or nine months in the schools – it’s a difficult life.”

The games in the theater “let them use their voices and their bodies, to feel joy and make them laugh,” he says. “It’s space where we share a human language. We laugh together; we clap together. They dance from the beginning to the end. They have energy. They need to get this energy out.”

Such moments of joy are in short supply for many of the other tens of thousands of Lebanese who fled the border region. The majority now live in safer areas, staying with family members or in rented accommodations, but after eight months of war, resources and goodwill have run thin or been depleted altogether.

When this war began, many expected a scenario similar to that of 2006, when the last major Hezbollah-Israel battle destroyed much of southern Lebanon, but was also over in 33 days.

“At the beginning, the Lebanese people did panic. ... You saw a lot of preemptive displacement; people thought the sky would fall on their heads,” says Maureen Philippon, the Lebanon country director for the Norwegian Refugee Council, which supports the displaced and some of the 60,000 Lebanese estimated to remain within 6 miles of the border.

Lebanon is confronting a national economic slide that has left half its citizens and more than 90% of Syrian and Palestinian refugees living here living below the poverty line, and relief agencies and the United Nations already face cash shortages.

Nongovernmental agencies like the Norwegian Refugee Council planned for worst cases such as the entire south of Lebanon being cut off. Early on, under the assumption that supermarkets would be closed, food parcels containing a two-week dry food ration and household cleaning products were standard for those who remained.

“We are still keeping ready for worst-case scenarios, but because everyone learned to live in that environment [of continuing conflict], cash makes more sense,” says Ms. Philippon, of how assistance is often distributed now.

“We’ve seen an intensification of the fighting, in both ways,” she adds of the Hezbollah-Israel exchanges of recent weeks. Though it’s been quieter the last few days, overall this front has seen “flare-ups, and an increase in violence, that are more intense, more frequent, and last longer in time.”

“The stress on the families who stayed there – and the kids, in a number of families we interviewed – the psychological effect of the bombing, the noise, the fear, is super heavy,” she says.

Indeed, the toll of living away from home for so many months has been high for many. One farmer fled to Beirut with his wife three days after the war began. On the sixth day, his neighbors reported that his house had been destroyed in an Israeli strike.

“I am willing to go back now, put a tent on the rubble of my house, and stay,” says the farmer, whose house of three decades used to be 500 yards from the Israel border. The farmer, who withheld his name for security reasons, says he pines for the fresh air, the tasty crunch of his own produce, and quiet nights.

The eight-month stay squeezed in with his son’s family in Beirut has been so stressful that his wife has been admitted to a hospital for anxiety. Their savings were used up long ago. The farmer now sells vegetables from a street stall to keep busy, but he earns a pittance, and the long hours are not sustainable.

“A lot of us thought it would end quickly, but it keeps escalating every day,” says the farmer, whose face is creased from his eyes to the corners of his mouth. He breaks down in tears, and says he has considered ending his life.

“I can’t take it anymore,” he says, adding that he can’t afford to treat his wife.

“She had a lot of anxiety because of the bombing at the border,” he says. “We have a fear of watching TV, of watching houses being destroyed. When we watch the news, there is no sleep at night.”

Referring to the the belligerents in this war, he adds, “They can go to the mountains far away and fight day and night. ... I just want a house.”

Gangs have taken over Haiti. Schools must educate anyway.

Haiti has dealt with decades of political turmoil and natural disasters. Although there hasn’t been an uninterrupted academic year since 2017, schools here embody hope for a stabler future.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

-

By Websder Corneille Contributor

-

Doris Lapommeray Contributor

Neighborhoods in Haiti’s capital and surrounding metropolitan areas are turning into ghost towns as gang violence grows.

After decades of political turmoil, insecurity, and repeated devastating natural disasters, Haiti is no stranger to crisis. It hasn’t had a presidential election in seven years, and the former prime minister was forced by powerful gangs to step down in March.

Despite these real challenges – and the constant refrain that the Caribbean nation has hit rock bottom – Haitians are adept at meeting crises head on. One need not look further than the country’s primary and secondary schools to understand the extent of Haiti’s troubles, as teachers and administrators scramble to educate a generation otherwise lost to insecurity.

“I wanted to do something that could have a tangible positive impact on the lives of Haitians,” says Ralph Ganthier, director of Collège Florian Ganthier. The private school has been operating for more than four decades in the Port-au-Prince suburbs but had to revamp its education services amid a spike in gang violence this year. “I deeply believe that education is the way.”

Gangs have taken over Haiti. Schools must educate anyway.

Route de Frères is a major artery connecting the heart of Port-au-Prince with nearby suburbs, typically flanked by open-air markets, crowds of students making their way to school on foot, and a cacophony of bumper-to-bumper traffic.

But on a sunny morning this spring, the thoroughfare was eerily empty – slowly becoming the new normal.

It’s just one result of gang violence that has spiked since 2021 and spiraled since the spring, forcing entire neighborhoods into lockdown today.

After decades of on-again, off-again political turmoil, insecurity, and repeated devastating natural disasters, Haiti is no stranger to crisis. It does not have an elected leader and hasn’t held a presidential election in seven years. In March, the former prime minister was forced by increasingly powerful gangs and loss of support from the United States to step down. Interim Prime Minister Garry Conille, appointed by an interim presidential council, took office in late May.

Despite these real challenges, Haitians are adept at meeting crises head on. And one need not look further than the country’s primary and secondary schools to understand the extent of Haiti’s troubles, as teachers and administrators scramble to educate a generation otherwise lost to insecurity.

“We are no strangers to interruption,” says Ralph Ganthier, director of Collège Florian Ganthier (CFG). The private Christian K-12 school off Route de Frères is running one month later than the school calendar to make up for the weeks of canceled classes due to violence this year. “We haven’t had an uninterrupted school year since 2017.”

A history of crisis

Haiti is home to the first successful revolt of enslaved people, which led to its independence in 1804. Since its emergence as the first Black republic, Haitians have struggled to establish a state that lives up to its promise of liberation. This includes facing external economic pressures such as an indemnity to France for recognition as a state, and internal failures of the elite economic and political classes to embrace democratic principles. The U.S. invaded Haiti in 1915 and ran it until 1934. From 1957 to 1986, the father-son Duvalier dictatorships dominated political life.

The most recent security crisis in Port-au-Prince began in 2021, following the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse. Since then, armed groups have strengthened their control of the capital and parts of the nearby Artibonite department through kidnappings and homicides, and by driving people out of their homes with threats. Some 580,000 Haitians are displaced across the country, according to the International Organization for Migration, a 60% increase since March.

In neighborhoods like Pétion-Ville, where CFG is located, makeshift barricades made of sacks of sand have been erected to deter unwanted groups from entering the area. In late March, a bloody gunfight took place near the school between police and their citizen supporters, and armed groups. Two popular gang leaders were killed.

Florian Ganthier, Mr. Ganthier’s father, founded CFG in 1980. In the four decades since, the Ganthier family and the school have navigated multiple complicated political and social emergencies with resourcefulness, creativity – and urgency.

The younger Mr. Ganthier recalls that when he was a child in the early ’90s, the international community imposed a trade, fuel, and arms embargo on Haiti after its army ousted what was considered its first democratically elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Because of fuel shortages, public transport took a hit, and “most schools had to shut down,” says Mr. Ganthier. “But my parents found a way to keep the school running by adopting a three-day week.”

In January 2010, a devastating earthquake hit the capital. It caused an estimated 300,000 deaths, displaced more than a million people, and damaged nearly half of all structures in the greater Port-au-Prince area. CFG was severely damaged, forcing the school to move to the concrete building it currently occupies.

“Reopening was nearly impossible,” says Mr. Ganthier, who had returned to Haiti only three days before the 2010 quake after working and studying abroad for four years. “We were unable to pay our teachers. It took months to find an alternative plan and negotiate a deal with our [staff] that could help us resume classes,” he says. The school finally opened three months later, in April 2010, a better outcome than that of many educational institutions in Port-au-Prince.

Chipping away at progress

The earthquake has had long-lasting consequences for Haitian politics.

“You need to go back to the 2010 earthquake and the 2011 presidential elections that followed it” to really understand what’s going on in Haiti today, says Vélina Élysée Charlier, a political activist and member of Nou Pap Dòmi (We Will Not Sleep), an anti-corruption collective.

The international community pressured Haiti to hold elections before it was ready, when much of the country was still under rubble and in survival mode. Haitian experts warned the nation wasn’t ready to “hold well-organized and fair elections,” says Ms. Charlier. That external push brought to power a party with ties to the country’s former dictatorship, and for the past 12 years, it has pillaged state coffers, armed and funded gangs, and weakened Haiti’s institutions.

The government was “never designed to serve us in the first place,” says Sabine Lamour, professor of sociology at the State University of Haiti and currently visiting faculty at the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Brown University. “A crisis implies that what is happening is abnormal, an out-of-the-ordinary unstable situation with impending change. But we are in a society where political troubles and instability have been the daily lives of Haitians since 1806.”

Mr. Ganthier, who took over CFG in 2010, says despite the school’s staying power, the country’s recent instability has chipped away at his family’s work.

Before 2021, for example, fewer than 5% of CFG students failed state exams. Last year, the number was 31%, according to school records.

“The [security] situation has had a major psychological effect on the children. They’re not at peace. The child can’t do their homework because they are always in a state of anxiety, so we have to be understanding of ... the trauma that exists,” he says.

Education “is no longer a right, but a privilege” in Port-au-Prince, says Christon St. Fort, director of the Federation of Protestant Schools of Haiti, a network of 3,000 schools to which CFG belongs.

“Each school tries to address the challenges. ... Some schools have no choice but to shut down,” says Mr. St. Fort.

“Education is the way”

In October 2022, the U.S.-backed interim government requested a multinational security force to combat Haiti’s deadly gang violence. After a year of back and forth, the United Nations Security Council approved sending a Kenya-led foreign mission to Haiti, which has yet to materialize.

Over the past three years, calls for a locally led, Haitian political solution have grown. Yet the international community has not been receptive, Dr. Lamour says.

Haitian schools, tasked with educating the nation’s future leaders, have been left to improvise. So far this year, due to security challenges, CFG students were only permitted on campus for two weeks in January, and then the school shuttered for six weeks straight between the end of February and April.

“Online teaching does not solve the problem,” says Mr. Ganthier. “Most of our students come from underserved neighborhoods and usually can’t afford a reliable internet connection; when they can, they are dealing with electricity” cuts.

As a temporary solution, CFG teachers prepare homework packets that families can pick up from the school secretary, Mr. Ganthier says. Students then turn in their work via the messaging application WhatsApp.

But this implies a relatively stable home and family life. When armed groups started displacing entire neighborhoods in downtown Port-au-Prince, CFG received new students whose families fled to the suburbs in search of security. But they’re losing families, too.

“When students leave, we simply stop seeing them. We don’t know they’re gone until we receive a call from another school requesting their transcripts,” says Mr. Ganthier.

The enduring nature of Haiti’s unrest raises concerns about the country’s future.

“All the things that made me love Haiti when I was a kid – traveling, the beach, friends – are less accessible to” my children, says Ms. Charlier. “It makes me worry about their connection to our home. And makes me think that they will choose to leave one day and never want to return.”

To Mr. St. Fort, what’s at stake is the very future of Haitian society. “If schools close, more young people will join the ranks of the gangs. Now more than ever ... we need to protect Haitian children’s right to receive a high-quality education.”

Through it all, what keeps Mr. Ganthier going is his profound sense of duty to his country and his family.

“I wanted to do something that could have a tangible positive impact on the lives of Haitians,” Mr. Ganthier says. “I deeply believe that education is the way.”

This story was produced with support from the Round Earth Media Program of the International Women’s Media Foundation, in partnership with Woy Magazine.

Podcast

It’s much bigger than Caitlin Clark: Our writer tallies women’s recent gains

A star hooper’s arc from college to helping elevate the women’s pro game is one small measure of broader progress. Two years after leading a deep report on Title IX’s 50th anniversary, a Monitor reporter updates us on each of the three braided strands in that legislation’s legacy.

Caitlin Clark’s first postcollegiate season is one storyline in women’s sports. Women’s sports is one storyline in the accounting of continued progress for women in the United States under 1972’s Title IX.

Two years ago this week, writer Kendra Nordin Beato joined the Monitor’s weekly podcast to talk about her cover story on the 50th anniversary of Title IX: legislation that braids education, sports, and protections against sexual harassment and assault.

“The hundreds of class action suits that these 37 words launched in the 1970s were all about creating equal opportunity for women in education,” Kendra says in this updated encore episode. “Women now sit in the president’s office in 30% of the nation’s 146 R1 research universities,” Kendra says. “And that is a 22% increase from 2021.”

Title IX-related regulations emerging this summer hint at big shifts in how institutions receiving federal funding are addressing harassment and assault allegations, she notes.

And sports? There’s the best-ever representation by women at the upcoming Olympics in Paris, Kendra says. And there’s Ms. Clark, making those “logo 3s.”

“This women’s sports fan,” says Kendra, “is just heartened by the fact that everybody’s talking about women’s sports.” – Clayton Collins and Jingnan Peng

Find story links and a transcript here.

Title IX at 50 Plus Two

Essay

In summertime, picking buckets of berries (with bears)

The long, languorous days of this season may just be the ideal time to revisit childhood memories of summers past. As our essayist discovered, simple pleasures never go out of style.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Noah Davis Contributor

Blackcap raspberries are the first true present of wild summer, ripening in central Pennsylvania as June slides in to July. These aren’t August’s blackberries. They carry more sugar and are smaller, more delicate.

My family would go out and pick together, each of us carrying an empty plastic gallon tub of Stewart’s ice cream. After hot days gave way to humid evenings, we’d descend, trying to beat the birds and bears to the harvest.

One night, we picked along a bank where a bear had been feeding. The signs were clear: torn logs, purple scat, berry-stripped patches. Still, we never expected a bear to hang around with humans near. Particularly on land where bears are heavily hunted.

Yet berries will make one linger – human and bear – and so when we were no more than 15 steps away, a bear broke through a ruined barbed wire fence and bolted across the road. In a blink, he’d been swallowed by the creek bed beyond.

We were silent for a long time, in awe of our close neighbor in this shared meeting place.

In summertime, picking buckets of berries (with bears)

I have enough self-confidence, or delusion, to believe that whatever world I find after this one will be pleasant. And in my dreaming, I envision I’m welcomed into what an Irish poet long ago called a “bee-loud glade,” with a bowl of vanilla-bean ice cream covered in blackcap raspberries. The dark fruit will hold just enough midsummer sun to soften the frozen scoops, and my teeth won’t ache from the cold.

“There is another world,” a famous quote goes, “but it is in this one.” What else could tie the two worlds together better than the berries that grow from canes purple as memory? These aren’t August’s blackberries. They carry more sugar and are smaller, more delicate, the first true present of wild summer, ripening in central Pennsylvania as June slides in to July. When picked, the raspberry reveals a perfect cap as if you’d pulled a bald man’s wig from his head.

My family would go out and pick together, each of us carrying an empty plastic gallon tub of Stewart’s ice cream. Blackcap thorns aren’t daggerlike in the same way the cockspurs of blackberries can be. They’re smaller and less punishing, but they still catch against clothing and skin. The scratches on hands and forearms carve a shallow map of the hours spent picking. The berries are a species in love with disturbance, and so the canes are not under the thick canopy that covers the mountains, but rather in places where humans have opened the dirt to the sky: along railbeds, under telephone wires, along roadside ditches.

After hot days gave way to humid evenings, we’d descend, trying to beat the birds and bears to the harvest. These were the moments I first felt ursine. I couldn’t stay still as a child, but the crushed canes in the shape of a black bear’s rump showed me how to wallow in one place. How to pick deliberately. There were always berries hiding under leaves near the ground, visible only from a different angle. It paid to wait for them to appear, not to rush past simply picking the most obvious fruit.

One night, we picked along a bank where a bear had been feeding. The signs were clear: torn logs, purple scat, berry-stripped patches. But we often called to each other when someone disappeared behind the thick green foliage, or cursed when we tripped on a log and fell into the thorns, so we never expected a bear to hang around with humans near. Particularly on land where bears are heavily hunted.

Yet berries will make one linger – human and bear – and so when we were no more than 15 steps away, a bear broke through a ruined barbed wire fence and bolted across the road.

In a blink he was on the macadam, and in another he’d been swallowed by the creek bed beyond, likely heading for another patch that bloomed from a 2-year-old logging road on the opposite ridge. We were silent for a long time, in awe of our close neighbor in this shared meeting place.

My family measured foraging success in gallons. Six frozen tubs carried the family of four through a whole year of oatmeal and pancakes.

In the best season, in the year when so much rain fell that the river forgot its banks for a month, we picked 5 gallons in a single afternoon. Instead of reaching with thumb and forefinger, I grabbed by the handful.

But the bounty’s window doesn’t stay open for long. The berries are only ripe on the canes for two weeks if the nights are cool enough. We had to freeze most to keep them from spoiling, stacking them on last year’s wrapped venison to retrieve every morning throughout the year to sweeten our breakfasts. We only ever saved a cup or two fresh for ice cream. But on four or five nights each summer, fresh blackcaps floated on half-frozen rivers of cream and sugar, an idyllic moment of summertime rapture.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Celebrating diversity in the lab

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

On June 23, women who are trained to invent, build, and fix today’s technology will celebrate International Women in Engineering Day. Started in Britain a decade ago, the celebration – and that is the main point – has since gone global. And for good reason. The number of women researchers in all technical fields worldwide is approaching parity with men.

A new study found that women were 41% of researchers in 2022 compared with 28% in 2001. In a few fields as well as in a few countries, women have already reached parity.

The annual celebration for women in engineering began in 2014 as a way to shift the narrative about the difficulties women face in research institutions traditionally dominated by men. “By nurturing and promoting positive role models, we can create a future where the barriers we faced no longer exist,” said Dawn Childs, recent president of Britain’s Women’s Engineering Society.

“By shifting the conversation away from the negatives of being a woman in engineering, we can redirect our focus towards the immense potential we possess to make the world a better place through our problem-solving abilities,” she added.

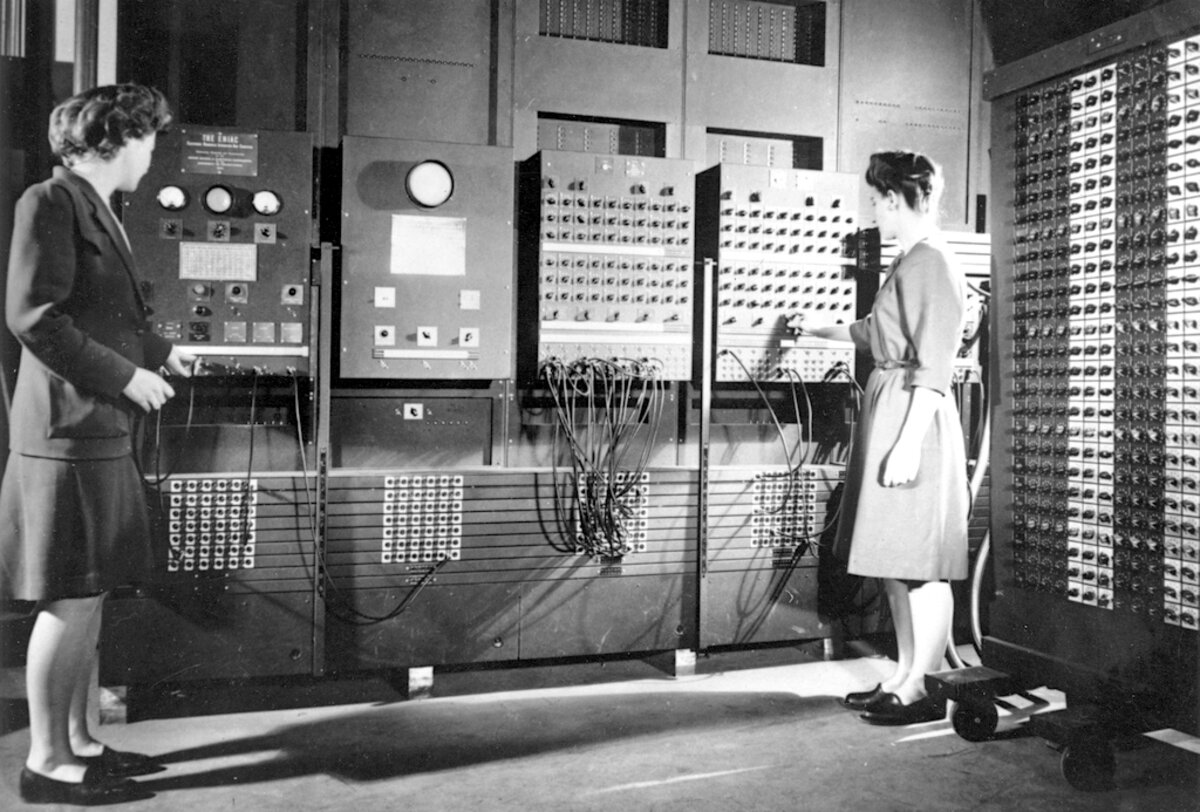

Celebrating diversity in the lab

On June 23, women who are trained to invent, build, and fix today’s technology will celebrate International Women in Engineering Day. Started in Britain a decade ago, the celebration – and that is the main point – has since gone global. And for good reason. The number of women researchers in all technical fields worldwide is approaching parity with men.

A new study by a Dutch scientific academic publishing company, Elsevier, found that women were 41% of researchers in 2022 compared with 28% in 2001. In a few fields such as chemistry, as well as in a few countries such as Portugal, women have already reached parity. And the most experienced female researchers have their scholarly work cited in publications more often than male researchers do.

The annual celebration for women in engineering began in 2014 as a way to shift the narrative about the difficulties women face in research institutions traditionally dominated by men. “By nurturing and promoting positive role models, we can create a future where the barriers we faced no longer exist,” Dawn Childs, recent president of Britain’s Women’s Engineering Society, told The Manufacturer.

“By shifting the conversation away from the negatives of being a woman in engineering, we can redirect our focus towards the immense potential we possess to make the world a better place through our problem-solving abilities,” she said.

This upward trajectory for women in research has required more than fighting gender bias. Women have become adept at networking to learn the ropes and climb the career ladder. They are figuring out ways to navigate the first several years in research, work-life balance, and scholarships. After one workshop in Singapore for women in science and technology, one participant said she discovered “more about myself and how to communicate with the partners around me.”

As the gender gap narrows for women in research, many in their fields recognize that innovation relies on a broad concept of diversity beyond gender balance. A work environment that includes many unique perspectives and experiences helps foster innovation, as shown by a 2017 study by Boston Consulting Group. A yearly event to celebrate the advances of one particular group – women engineers – opens doors for others.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The pathway to health is bright

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 1 Min. )

In seeking healing through prayer, we can move past blocks and be free of heavy burdens.

The pathway to health is bright

When reading the Gospels, we encounter Christ Jesus healing individual after individual, bringing freedom from sickness and disease of all kinds. In our own lives, maybe health doesn’t always feel so accessible.

But Jesus said that he’s “the way,” and that his burden was light. He showed that finding health isn’t a drudge or ever impossible. Following him is joyful. There are myriad accounts in the archives of The Christian Science Publishing Society that illustrate how, even without the physical Jesus around, healing through prayer is within reach, and nothing’s truly holding us back from it. Here’s a selection of those experiences.

“The joy of affirming health” describes how prayerfully pursuing the truth of our spiritual wholeness can be a joyful venture that leads to a quick cure.

The author of “Uplifted outlook and renewed eyesight” illustrates that witnessing God’s limitless love for us can naturally restore our faculties to normalcy.

“The ‘eternal noon’ of existence” relates how we have the authority to challenge the widely held expectation that we’re doomed to suffer from age-related injuries as we mature, through the confidence, and evidence, that as God’s child our health is free of any material measurement of time.

In “To calmly persist,” the author shares that we can overcome protracted or seemingly incurable problems as we open ourselves to the truth of our eternal wellness, and find that there’s hope and joy at every step.

Viewfinder

A new day, an ancient site

A look ahead

Thanks for being part of the Monitor community this week. Come back Monday, when Howard LaFranchi will report from a Ukrainian village once occupied by Russian forces, where resident Staryi Saltiv straddles two outlooks: hope for a better future and trepidation that Russian troops could return.

And we’ll leave you with a bonus read: Hawaii is the latest place where youth-led activism is resulting in new efforts to tackle climate change – a trend known to Monitor readers from our Climate Generation series.