- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Why a Palestinian plan to revive Gaza and democracy faces doubt and distrust

- Today’s news briefs

- Forget 1968. The DNC is underway in Chicago with minimal disruption.

- How Venezuela’s opposition leader went from political fringe to center stage

- Biden says he’s ‘too old to stay as president.’ It shows the pull of ageism.

- Senior housing that doesn’t isolate, and how community lifts Mexican women farmers

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Warning: You are entering a prediction-free zone

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

One of the less-helpful things the media does is predict things: elections, wars, economic trends. First, we’re usually wrong. Second, predicting doesn’t really help understanding.

Today’s Monitor presents an alternative. Many people are trying to predict what will happen in Gaza or Venezuela. What we do, instead, is look at where people are working toward outcomes.

Of course, we don’t know what will happen. But the future is made by those working to shape it. Wars will end. Elections will finish. Who is working toward that moment, and what variables are in play? That’s more than guesswork. It’s constructive journalism.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Why a Palestinian plan to revive Gaza and democracy faces doubt and distrust

Can institutions reform themselves? It’s a question being tested in the midst of war. The Palestinian Authority has launched an ambitious plan to democratize and provide for Gaza’s future, but its leadership is deeply distrusted by the Palestinian people.

-

Fatima AbdulKarim Special contributor

The team of policymakers working to overhaul Palestinian governance has a dramatic checklist: Build a representative, democratic Palestinian Authority. Prepare for the governing and rebuilding of Gaza. Unite a fractured society.

By “revitalizing the Palestinian Authority,” as President Mahmoud Abbas has tasked his government with doing, they believe they can create a democratic entity that can peacefully govern both Gaza and the West Bank – and lay the foundations of an independent state.

Since businessman Mohammad Mustafa was tapped in April to form a Cabinet of technocrats with backgrounds in the World Bank and the United Nations, his team has raced to complete a two-year plan. The international community is counting on it. The Biden administration has pushed a “revitalized PA” as key to a post-Hamas Gaza.

The problem? These would-be reformers lack money and popular support, and face an overtly hostile Israeli government. Rather than heed calls for a broad unity government, the autocratic Mr. Abbas handpicked Mr. Mustafa, an ally, without consultation.

As a result, the reform government lacks the backing of Palestinian factions, even from within Mr. Abbas’ own Fatah party.

“We will not work against you,” one senior Fatah official recalls telling Mr. Mustafa in April, “but we will not work with you. And you need us.”

Why a Palestinian plan to revive Gaza and democracy faces doubt and distrust

The team of policymakers working around the clock here to overhaul Palestinian governance has a checklist of proposed reforms that are a Western diplomat’s dream.

Build a representative, democratic Palestinian Authority (PA). Foster an inclusive society. Prepare for the governing and rebuilding of Gaza. Unite fractured political groups and social institutions.

The policy to-do list includes education, renewable energy, and business opportunity.

By “revitalizing the Palestinian Authority,” as PA President Mahmoud Abbas has tasked his government with doing, the team believes it can create a unified democratic entity that can peacefully govern both Gaza and the West Bank – and lay the foundations of an independent state.

But there’s a problem.

These would-be reformers lack both money and popular support, and face domestic political opponents hoping they will fail. And the Israeli government is overtly hostile to the PA and Palestinian independence.

Nevertheless, they say they are fighting for what one reformer describes as “the last best chance” for peace – even as the region teeters on the edge of a wider war and the PA faces financial collapse.

And the international community is counting on them. The Biden administration has pushed a “revitalized PA” as key to a post-Hamas, postwar Gaza.

“Our people want to see reforms,” says Wael Zaqqout, minister of planning and international cooperation in the reformist government. “They want to see a government that is effective, responsive, and provides services in a dignified way.”

Gaza first

Since businessman Mohammad Mustafa was tapped as prime minister in April to form a Cabinet of technocrats with backgrounds in the World Bank and the United Nations, his team has raced to carry out a two-year plan to overhaul the PA and govern Gaza.

Its top priority is “relief and recovery” for the Gaza Strip – facilitating lifesaving aid and preparing teams to restore electricity, water, and sanitation “to make the life of people less painful,” Mr. Zaqqout says.

In the meantime, the technocratic government is looking for people to fill government posts in Gaza and is integrating West Bank and Gaza legal codes and institutions so that the PA can administer the strip as soon as the war ends.

The other major pillar for its Gaza plan: long-term rebuilding coordinated by an independent Gaza reconstruction agency and bankrolled by a trust fund to be established at the World Bank.

The team’s vision: a postwar Gaza full of new housing complexes, powered by solar and wind energy and served by a large-scale desalination plant and a functioning port.

“We are absolutely committed to rebuilding Gaza, and we will make it greener, and cleaner, and better. Rebuild better,” says Mr. Zaqqout, a former World Bank official whose family hails from Gaza. “We need to bring hope to people that their homes will be rebuilt, their lives will be rebuilt.”

Once the war ends, the PA team plans to take its reconstruction vision to Gaza to widely consult residents, and amend it with their input.

Transforming the PA

The technocrats’ other main objective is a series of democratic reforms converting the corruption-wracked PA into a transparent, responsive government.

At the core of these reforms are an independent government auditor and an anti-corruption commission.

In a judicial overhaul, the president would no longer make senior judicial appointments – an indirect acknowledgment that the autocratic Mr. Abbas has stacked the high courts with lackeys.

The government says it will complete these overhauls by 2025.

Other proposed reforms include the following:

- Improve PA finances by collecting import duties at the borders with Jordan and Israel while removing red tape for entrepreneurs.

- Amend a draconian cybercrimes law that has been used to curb dissent.

- Introduce a mandatory “civics course” to teach Palestinian children democracy, diversity, separation of powers, and respect for others.

One reform especially prized by Washington is the government’s commitment to end monthly stipends paid to families of Palestinian prisoners and those killed by the Israeli military.

PA ministers say they will suspend the authority’s Martyrs Fund and Prisoners Fund, which support families of those killed or imprisoned by Israel – criticized by Israelis and others as “pay to slay” programs, but on which thousands of Palestinian families rely.

Instead, they say they are developing a new social safety net under which the authority would provide assistance to families based solely on socioeconomic needs.

Overhauling the welfare system would put the PA in line with U.S. law, which suspends U.S. aid to the authority if it continues these stipends.

Yet senior Palestinian politicians decry the plan. One calls it “reducing heroes of the resistance to unemployed welfare dependents.”

On the political front, Prime Minister Mustafa’s government says it is taking steps to strengthen the electoral commission to prepare for “free and transparent” parliamentary and presidential elections by March 28, 2026 – two years after the technocrat government’s appointment.

By 2026, the government hopes to have the reforms completed and a new elected Palestinian government administering both the West Bank and Gaza, with the foundations of a state in place.

Headwinds and history

One immediate challenge facing the reform government is a lack of credibility among Palestinians.

Rather than heed Palestinian and international calls for a broad unity government, Mr. Abbas, whose term in office was to have ended years ago, handpicked Mr. Mustafa, an ally, without consultation.

As a result, the reform government lacks broad support from Palestinian factions. It is not unanimously popular even in Mr. Abbas’ own Fatah party.

“We will not work against you,” one senior Fatah official recalls telling Mr. Mustafa in a meeting in April, “but we will not work with you. And you need us.”

Hamas rejects the reformist government and has called for a new technocratic government to be formed with the involvement of all factions, in line with a unity agreement reached by Palestinian groups in Beijing last month.

“I believe this government will suffer the fate of all other governments before it, as it was not discussed or negotiated with other factions,” says Basem Naim, a former Hamas health minister. “It will fail.”

The Democratic Reform faction of Fatah is calling on Mr. Abbas to step aside. “We believe the only way out of this domestic mess ... that Abbas has put us in is through elections,” says Dimitri Diliani, the faction’s spokesperson. What happens the day after the war ends “should be up to the people.”

Polls indicate that the Palestinian public, mindful of previous failed reform efforts, has little faith in this new one.

In a June poll by the Ramallah-based Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research, 72% of Palestinians surveyed in the West Bank and Gaza said they believe the Mustafa government will fail to carry out reforms, 77% believe it will not tackle corruption, and 71% believe it will fail in providing relief or rebuilding Gaza.

In the same poll, 69% viewed the PA as a “burden.”

Financial chokehold

But all Palestinians – supporters and detractors of the PA alike – agree that the biggest challenge facing the technocrats’ reform drive is Israel’s refusal to hand over the authority’s funds.

Or, as Planning Minister Zaqqout describes it, “the elephant in the room.”

Under a 30-year-old temporary agreement, Israel collects Palestinian customs duties and taxes on behalf of the PA and transfers them to the Palestinian government. The arrangement was to have been scrapped upon completion of a treaty recognizing a Palestinian state, but it is now a political football.

Many of the funds have been held hostage by the far-right Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who has repeatedly choked off the $170 million per month in taxes that comprise 60% to 70% of the authority’s total revenues.

In April and May, Mr. Smotrich blocked all cash transfers after several European states recognized Palestinian statehood, marking the first time since the Oslo Accords that Israel declined to transfer a single dollar to the PA.

Israel has refused to transfer the money used to pay salaries of PA staff in Gaza, some $70 million per month, since Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack. When it finally transferred $130 million to the PA in June, it deducted $34 million for payment to Israeli victims.

Meanwhile, the domestic revenue the PA collects locally has shrunk by 50% since Oct. 7 due to economic collapse in the West Bank and Israel’s denial of permits to some 200,000 Palestinian laborers to work in Israel.

With Gaza under siege and the PA surviving on only 35% to 40% of its normal budget, “there is no way we can talk of reconstruction in Gaza,” says Naser Abdelkarim, an economic analyst and consultant on previous Gaza reconstruction efforts.

Initial reforms, such as publicly posting the authority’s budgets and clamping down on fiscal waste, show “there is still hope, but it is not the significant breakthrough” needed, Mr. Abdelkarim adds.

In May, the World Bank warned that the PA’s financial condition had “dramatically worsened” in 2024, raising the prospect of an “imminent fiscal collapse.”

“The Israelis are not transferring our tax money to the government to pay salaries for teachers, health care providers, policemen, and others,” says Mr. Zaqqout.

Help from Europe

One ray of hope is coming from the European Union, which sees the Mustafa government as a rare source of progress.

This month the EU provided the PA with €400 million in grants and loans in what European diplomats variously describe as a vote of confidence in the government’s reforms and a way to “keep the authority alive.” The cash influx allowed the PA to pay nearly 70% of employee salaries for the month of July.

“The European Union fully supports the Palestinian National Authority government’s reform plan, and we will do everything we can to make sure it gets the funding it needs,” says a senior EU diplomat in the Middle East who declined to be named. “This is in the interest of regional stability, and Israel, not just the Palestinians.”

Yet it remains unclear whether money from international donors will allow the government to meet its two-year goals – or even survive the year.

“Help us. We need your help,” says Mr. Zaqqout, addressing the international community, warning that “a window for hope” threatens to close. “We are tired of killing and destruction and think there might be a window to salvage the situation,” he says.

“We have the plans” he insists. But “if people don’t trust the government to pay salaries, take care of them and protect them, it will be very difficult to do these reforms.”

Today’s news briefs

• Trump campaign hack: U.S. intelligence says Iran is likely behind the attack, casting the cyber intrusion as part of an effort by Tehran to interfere in American politics and to undermine faith in democratic institutions.

• Corporal punishment in schools: The governor of Illinois signed a law this month that will ban physical punishment in private schools while reiterating a prohibition on the practice in public schools.

Forget 1968. The DNC is underway in Chicago with minimal disruption.

After pro-Palestinian encampments disrupted college campuses this spring, many predicted major clashes at the Democratic National Convention – a repeat of 1968’s DNC. But so far, the protests in Chicago have been smaller than expected.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Pro-Palestinian organizers convened their March on the Democratic National Convention on Monday with great fanfare but fairly small numbers. Organizers had predicted that they might draw as many as 40,000 people – four times the number of anti-Vietnam War protesters that showed up in Chicago in 1968. But Monday’s protest, a mostly peaceful event with at most a few thousand participants, was small enough that hundreds of protest signs sat unused in piles.

Many said they saw little difference between President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on Gaza. But the size of the crowd suggested that some of those who feel fury at Israel aren’t as mad at the vice president. Polls indicate that since Ms. Harris became the nominee, she’s made massive gains over President Biden among constituencies that have been most supportive of the Palestinian cause, including young voters and voters of color.

“If it was still Biden, I think there would be a lot more people out here,” said Brendan M., a protester from Chicago who declined to give his last name.

There are still three days and nights left to go. But so far, nothing has disrupted Democrats’ coronation of Vice President Harris as their nominee.

Forget 1968. The DNC is underway in Chicago with minimal disruption.

This isn’t 1968.

The Democratic National Convention kicked off in Chicago amid dire predictions of a replay of the party’s ’68 gathering. That’s when riots and police attacks on anti-war protesters outside the convention combined with a messy floor fight inside the hall to derail Democrats’ chances at the White House.

For now, at least, there’s no comparing the two.

Pro-Palestinian organizers convened their March on the DNC on Monday with great fanfare but fairly small numbers, leading a mostly peaceful protest of a few thousand people that in both scale and impact paled in comparison to the disruptive events of a half-century ago.

Rally speakers and many participants said they saw little difference between President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris on Gaza. But the size of the crowd suggested that some of those who feel deep sympathy for Gaza residents and fury at Israel aren’t as mad at the vice president. Polls indicate that since Ms. Harris became the nominee, she’s made massive gains over President Biden among core Democratic constituencies that have been most supportive of the Palestinian cause, including young voters and voters of color.

“If it was still Biden, I think there would be a lot more people out here. It’s a very different attitude. I think people are hoping against hope that she’ll do the right thing,” said Brendan M., a protester from Chicago who declined to give his last name.

How Harris is viewed differently from Biden

Organizers had predicted last week that the protest might draw as many as 40,000 people – four times the number of anti-Vietnam War protesters that showed up in Chicago in 1968. But Monday’s turnout, at most a few thousand, was small enough that hundreds of protest signs sat unused in piles.

Vice President Harris hasn’t broken from President Biden on Middle East policy. But she has rhetorically expressed more sympathy for the plight of Palestinians in Gaza currently facing Israeli strikes and famine. More than 40,000 people have been killed in Gaza, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, since Israel began its war in the territory last fall triggered by Hamas’ attack that left more than 1,100 people dead in Israel. More than 85% of people in Gaza have been displaced from their homes.

April Ignacio, a vice chair of the Arizona Democratic Party, is a Harris delegate who joined the protest. She believes that the protest “absolutely” would have been much larger if President Biden were still the Democratic nominee. She personally is “far more excited” about having Ms. Harris at the top of the ticket because of the historic nature of her candidacy. “I’m going to get to vote for a Black female as the president,” she says. “I can’t believe that this is happening in my lifetime. And I’m excited about that.”

Daniel Smith, a protester from Kalamazoo carrying a “Michigan demands not another bomb” sign, says he’d been interviewed by more than a half dozen journalists eager to talk to a swing state protester – a sign of the outsized level of coverage, given the size of the protest. “We were hoping that there’d be more” fellow protesters, his friend Don Cooney says. “Of course.”

Mr. Cooney says he plans to vote for Ms. Harris. Mr. Smith is torn about how he’ll vote this fall. “I find it very hard to vote for somebody who’s enabled genocide, so it’s a difficult choice for me,” he says. But he is more open to backing Vice President Harris than he had been for President Biden, because “she has expressed more empathy for Palestinian suffering.”

Disruptions and a handful of arrests

Faayani Aboma Mijana, a spokesperson for the coalition that put on the event, says that in their view “not a lot has changed” from 1968 to now: “The Democratic Party is still a pro-war party, while claiming to represent working and marginalized people.” They argued the protest was “a strong turnout, given the fact that it’s a Monday and a workday.”

The protests Monday were mostly peaceful, though late that afternoon, a few hundred protesters pushed through the outer security perimeter, leading to a handful of arrests and a temporary shutdown of the security perimeter. That created bottlenecks and long lines for delegates and other attendees as the convention began, leaving the center itself half empty for early speeches. During President Biden’s address Monday night, a small group of protesters held up a banner that read “Stop Arming Israel,” but it drew little attention.

Things could have gone very differently.

For much of the spring and early summer, pro-Palestinian encampments on college campuses led to clashes, arrests, and heavy media coverage – and laid bare a major fissure in the Democratic Party. President Biden’s ongoing support for U.S. military aid to Israel, even as he criticized its disregard for civilian life in its campaign against Hamas, infuriated many on the left. The Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the metro area with the largest Palestinian population in the country, seemed a likely target for massive protests.

But former Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot scoffs at the 1968 comparisons.

“This is a different time, place, everything from 1968. The city continues to learn every year,” Ms. Lightfoot says in a brief interview inside the convention. “The police understand that the protesters have First Amendment rights.”

Chicago’s history with protests

Chaotic protests aren’t exactly ancient history in Chicago. Ms. Lightfoot, the first Black woman to serve as Chicago’s mayor, lost her 2023 reelection bid partly because of how she handled the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests and police response. The city has a long history of police violence and tensions between law enforcement and brown and Black communities.

Current Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, a former teachers union organizer and avowed progressive, replaced Ms. Lightfoot – then cast the tiebreaking vote to pass a city council resolution calling for a ceasefire in Gaza – a vote that many of the protesters celebrated.

Chicago Police Superintendent Larry Snelling was personally on hand to help coordinate the police response at the DNC. He walked ahead of the march on Monday evening as his officers steered protesters along a preapproved parade route that took them near the edge of the security perimeter around the United Center, the stadium hosting the convention’s evening programming.

There are still three days and nights left to go – and it’s worth noting that in 1968, it wasn’t until a few days into the convention that violence broke out in earnest. And more developments in Gaza could reignite protesters’ fury between now and the election. But so far, nothing has disrupted Democrats’ coronation of Vice President Harris as their nominee.

How Venezuela’s opposition leader went from political fringe to center stage

Venezuela’s government and opposition have both claimed victory in the July 28 presidential election. But it’s a woman whose name wasn’t even on the ballot who may be stealing the show.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

-

By Mie Hoejris Dahl Contributor

Venezuelans around the globe answered the call to protest by opposition leader María Corina Machado last weekend.

Although her name wasn’t on the ballot in last month’s hotly contested presidential vote, Ms. Machado is at the center of most everything in Venezuela these days. She’s at the helm of a movement to take the Andean nation in a new direction after a decade of increasingly authoritarian rule by President Nicolás Maduro.

But it wasn’t long ago that Ms. Machado was viewed as a fringe figure in Venezuelan politics – called a “fly,” a nuisance, during former President Hugo Chávez’s time in office, and even long derided by members of her own party. Her rise as a political – and increasingly spiritual – figure in Venezuela may say more about shifts in the population and its attitudes over the past two decades than about changes in her personal politics or approach.

“It is no longer about left or right,” says Eulice Villarroel, who considers himself a former chavista, a supporter of the political and social movement launched by Mr. Maduro’s predecessor Mr. Chávez. The July 28 presidential vote was a choice of “freedom and democracy [versus] dictatorship.”

How Venezuela’s opposition leader went from political fringe to center stage

Nearly three weeks after Venezuela’s hotly contested presidential vote, opposition leader María Corina Machado continues to lead the protest movement against President Nicolás Maduro and his government’s unsubstantiated claims of winning reelection.

Although she wasn’t the opposition’s presidential candidate (she was barred from running by the Supreme Court), Ms. Machado headlined the “Protest for the Truth” over the weekend, which brought thousands of Venezuelans and their supporters to the streets nationwide – and in places as far as Madagascar and Spain.

Ms. Machado is at the center of almost everything in Venezuela these days, not only hailed as the country’s political future, but also often characterized as a spiritual icon. It’s a striking contrast to the many years she was viewed as a radical, far-right politician, too extreme even for her own party coalition.

The once-fringe figure, who was nationally booed for proposing the privatization of Venezuela’s oil industry, has become a beacon of hope for Venezuelans yearning for change after more than a decade of economic and political struggles under Mr. Maduro’s increasingly authoritarian rule. And her rise may say more about Venezuela itself than about changes in her personal politics or approach.

“It is no longer about left or right,” says Eulice Villarroel, a former chavista, or supporter of the political and social movement launched by Mr. Maduro’s predecessor Hugo Chávez.

Today, he says, this political moment has become a matter of “freedom and democracy [versus] dictatorship.”

“Our last chance”

Earlier this summer, in the final days leading up to the July 28 presidential vote, Ms. Machado organized a caravan that drove nearly 435 miles from the capital, Caracas, to Venezuela’s second-largest city, Maracaibo. Crowds gathered in remote villages along the route, waving flags and handmade posters, and vying for a chance to interact with the politician. In Maracaibo, supporters held up posters heralding mantras like “Losing your fear is called liberty.”

Many credit her for garnering the opposition’s widespread turnout and popular support during the election – even though her name wasn’t on the ballot – the results of which have pushed Venezuela’s strongman leader into a corner.

“She is our last chance,” says Aleida Osorio, who owns a beauty salon in an upscale Caracas neighborhood. “She’s a leader with principles ... willing to risk it all.”

Venezuela’s electoral authority, considered loyal to the president, has said Mr. Maduro won a third term with nearly 52% of the ballots. The opposition says its candidate, former diplomat Edmundo González Urrutia, won 67% of the vote. The government is refusing to release paper tallies to verify the results, despite growing international pressure.

Before former President Chávez was elected in 1998, both rich and poor people here were disenchanted with the political elite. Mr. Chávez oozed charisma and won favor among the long-ignored poor population, feeding the country’s vast oil profits into social programing. When he died in 2013, already oil production – and global prices – were faltering. He was replaced by his handpicked successor, Mr. Maduro, who leaned into the growing economic hardship by cracking down on those questioning his leadership or the future of chavismo.

The opposition has tried seemingly everything to regain control of the country since the emergence of chavismo, but it has repeatedly failed to unite. Even when the opposition agreed on candidates to back, one after another fizzled. There have been disagreements on how to confront chavismo, and the opposition and its international allies have tried a wide range of approaches from imposing sanctions on the government to boycotting elections to setting up a parallel interim government.

Along the way, Ms. Machado was the butt of jokes from both the left and the right. Mr. Chávez belittled her in televised debates and his daily news conferences, referring to her as a “fly,” or a nuisance that could be easily swatted away. Even within the opposition, leaders mocked her.

Ms. Machado has proved many critics wrong, and not just in her staying power. She won the opposition’s primary elections in October with 92.5% of the vote. Venezuela experts say only Mr. Chávez was able to mobilize crowds like Ms. Machado now does.

What once seemed radical – she was one of the first to call chavismo a dictatorship and referred to the government’s expropriation of private land and businesses as “theft” – now has Venezuelans clamoring with approval.

“She hasn’t changed. She has always been the same. But we see her with different eyes now,” says Ms. Osorio, who has always supported the opposition but only recently started backing Ms. Machado. “What has changed are the [Venezuelan] people” who are fed up with corruption and perpetual crises.

Flexible – but firm

Ms. Machado has shifted her focus away from traditional left-right rhetoric, instead addressing core concerns that resonate deeply with Venezuelans: freedom, family reunification, and decent jobs for all.

This has helped her win over even former skeptics like Ibrahim Ruíz Castro, a driver in Caracas. Part of her appeal, he says, is that she is providing a realistic alternative to Mr. Maduro.

Ms. Machado’s adaptability is a hallmark of her campaign. “I believe one can and should be very flexible. In fact, I think we’ve demonstrated this with the strategy we’ve used to confront the regime in recent months because we’ve surprised them,” Ms. Machado told the Monitor in July, referring to how the opposition pivoted after she was barred from running for president, backing a new candidate in record time. “For that, you need to be agile, not predictable.”

“María Corina Machado has managed to unite people in a way that we have not seen the opposition united before,” says Ryan Berg, director of the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He points to her decades of preparation, courage to stand up to unprecedented government repression, and her charisma. “It’s just sheer personality; she’s ... a force of nature,” Dr. Berg says.

Ms. Machado has cultivated an almost religious presence in recent years. Many say they see her as their “savior” from the economic, political, and humanitarian challenges that have sent almost 8 million Venezuelans seeking refuge outside the country since 2014. She typically dresses in all white and adorns herself with handfuls of rosaries. Even with her name, María, she evokes biblical imagery. Last week, the Cuban exile community in Miami nominated her for the Nobel Peace Prize.

A number of the opposition’s campaign staff have been in hiding for months due to government threats and arrests. Despite threats from the government following the vote, Ms. Machado emerged from hiding on Aug. 17 to lead the opposition rally in Caracas. Mr. González remains in hiding.

As protests, counterprotests, and police crackdowns fuel political uncertainty right now, diplomatic efforts explore solutions to the electoral crisis with proposals like fresh elections or power-sharing agreements. Ms. Machado remains resolute that the opposition won – and should be in charge of moving the nation forward. She has rejected the idea of an electoral redo.

“I do believe that when it comes to ethics, one must be intransigent,” Ms. Machado says. “I think Venezuelans have become intransigent in that sense.”

Biden says he’s ‘too old to stay as president.’ It shows the pull of ageism.

Intense scrutiny of veteran politicians has prodded America toward greater awareness of how unchallenged ageism affects everyone, not just presidential candidates.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

A year of intense concern about the fitness of older national leaders to serve, culminating in President Joe Biden pulling out of the White House race, has surfaced what experts on aging see as a snowballing and largely unchallenged expression of the ageism that permeates American culture.

Pressure for Mr. Biden to withdraw probably had more to do with changing perceptions of his capabilities than with how many times he’s circled the sun. But from headlines to memes, the phrase “too old” – which the president himself used at the Democratic National Convention on Monday night – became ageist shorthand.

Gerontological advocates and scientists say public perceptions of older people are far too often anchored in unfair assumptions about the meaning of a numerical age. It’s a stereotype as unjust and incorrect as generalizations about race or gender – but somehow still acceptable. And it equates chronological age with poor health, which in turn fans fears of growing older.

Yet even some of those who see rampant ageism also see opportunity in the current moment.

“I personally think unless you see [ageism], you’re not going to do anything about it,” says Tracey Gendron, a gerontologist and author of “Ageism Unmasked.” She adds, “I am hopeful that maybe this will be a catalyst.”

Biden says he’s ‘too old to stay as president.’ It shows the pull of ageism.

A year of intense concern about the fitness of older national leaders to serve, culminating in President Joe Biden pulling out of the White House race, has surfaced what experts on aging see as a snowballing and largely unchallenged expression of the ageism that permeates American culture.

It’s not that the public is uniformly skeptical of octogenarians, like Mr. Biden. From politicians to business leaders and pop stars, many figures of older age enjoy wide acceptance as they continue to campaign, invest, and rock on. But gerontological advocates and scientists say public perceptions of older people are far too often anchored in unfair assumptions about the meaning of a numerical age, or about a slowing body equating with being slower of mind.

And those who study aging say that’s increasingly noticeable in public discourse.

For example, pressure for Mr. Biden to withdraw probably had more to do with changing perceptions of his capabilities than with how many times he’s circled the sun. But the proliferation of the words “too old” in headlines, memes, political polling, comedy routines, and social media became ageist shorthand. Indeed, Mr. Biden himself bought into the shorthand in his Democratic convention speech Monday: “Now I’m too old to stay as president.”

“Too old,” aging experts say, is a stereotype as unjust and incorrect as generalizations about race or gender. Except race and gender discrimination is widely unacceptable, while ageism is the “last acceptable prejudice.” And it equates chronological age with poor health, which in turn fans fears of growing older.

Yet even some of those who see rampant ageism – and its cousin “ableism,” with biases about disability – also see opportunity in the current moment.

“I personally think unless you see [ageism], you’re not going to do anything about it,” says Tracey Gendron, a gerontologist at Virginia Commonwealth University and author of “Ageism Unmasked.” “So, the positive here is that it raises awareness that ageism and ableism are freely floating throughout society.”

Monitor conversations with a half-dozen professionals studying the physical, mental, and social aspects of aging echoed Dr. Gendron’s dismay and hope.

Ageism is at least an increasingly familiar word. But Dr. Gendron says, “This whole conversation around politics has really set us back a step or two. Because you’re seeing so much more rhetoric about ‘too old.’”

Paul Kleyman, a journalist who has monitored ageism in the media for decades, dates the beginning of the spike in ageist rhetoric to the “legitimate worries” about the health of the late California Sen. Dianne Feinstein, which “turned speculative about other older members of Congress with no medical basis.”

“Those of us concerned about unanswered ageism in American culture watched the narrative load to a trigger point since early 2022, as we’ve not witnessed before. The Biden debate [performance] to me was a match to a kindling pile,” he says.

To some, the shift is that ageism has become more visible, not necessarily more widespread.

“I’m not sure ageism itself is on the increase. I think we’re paying more attention to what’s been there all along, and that Biden’s frailty supercharged the issue,” observes “This Chair Rocks” author and activist Ashton Applewhite.

How unchallenged ageism damages the public conscience

A World Health Organization report in 2018 targeted ageism as a pervasive global problem – “socially accepted and usually unchallenged.” Its effects, said the WHO, reverberate through economies in added health care costs and lost job opportunities, and it damages the public conscience of older and younger populations who internalize negative age beliefs.

The American gerontology field has understood this and worked assiduously in recent years to scientifically “reframe” aging positively.

Among problems these experts focus on are the effects of age segregation, from solitary isolation to grouping in islands of over-age-55 developments; and the antiaging – or “against aging” – health and beauty culture that pitches fear of growing older, even creating the “Sephora kids” tween market for wrinkle serums.

Some keep an eye on issues of fairness in such things as mandatory retirement or certifications for older people to drive or perform their work, and all concern themselves with how broadcasts of ageism are internalized among old and young alike.

Political reporting often “off the mark” over the past year

Politics have been the source of an “outbreak of ageism,” says James Appleby, CEO of the Gerontological Society of America, who, like his colleagues, spends much time managing misconceptions. “We get so comfortable with [stereotypes] that we never actually see what we’re doing. But for the [gerontological] community, a widespread feeling now is, ‘Wow, can you believe how off the mark some of the reporting can be?’”

Intense focus in the past year on struggling older politicians like the late Senator Feinstein, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, and President Biden often conflated their chronological age with missteps, physical appearance, and questions of health and cognition. With Mr. Biden, age 81, out of the race now, there’s evidence the age focus is being turned on former President Donald Trump, age 78. CNN commentator and former Obama White House adviser David Axelrod said before Mr. Biden’s convention speech, “Now the worn-out old incumbent is Donald Trump.”

And this all keeps aging professionals busy, repeating their singular mantra in interviews and op-eds: “If you’ve seen one 80-year-old, you’ve seen one 80-year-old.”

The point, explains antiageism author Ms. Applewhite, is that “the defining characteristic of aging is heterogeneity. ... There are as many ways to be 80 as there are 80-year-olds.”

That diversity is overlooked when the term “too old” is used to collapse aging “into a set of clichés and tropes,” explains Brian Carpenter, professor of psychological and brain sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s a stand-in for other things that I think they’re really concerned about, which is capability, cognition, energy, vitality.”

But, he adds, “It takes a lot more mental effort to think about a person’s experience, or their connections to world leaders, or their prior experience managing a crisis. It’s just harder for people to evaluate our candidates on those much more complex, abstract principles.”

Likewise, in political polling, experts say questions that lead voters to consider a candidate through the age lens are ageist because they misleadingly equate age with capability. An ABC News poll in early July by Langer Research Associates, for example, directly asked if respondents thought either, both, or neither of the presidential candidates was “too old” for a second term. Fully 58% responded “both.” (Neither the polling firm nor ABC responded to interview requests.)

“That’s not an informative way of framing the question, and it implies that there’s something useful about knowing someone’s chronological age, which really isn’t very valuable when evaluating someone’s leadership capabilities,” asserts Dr. Carpenter.

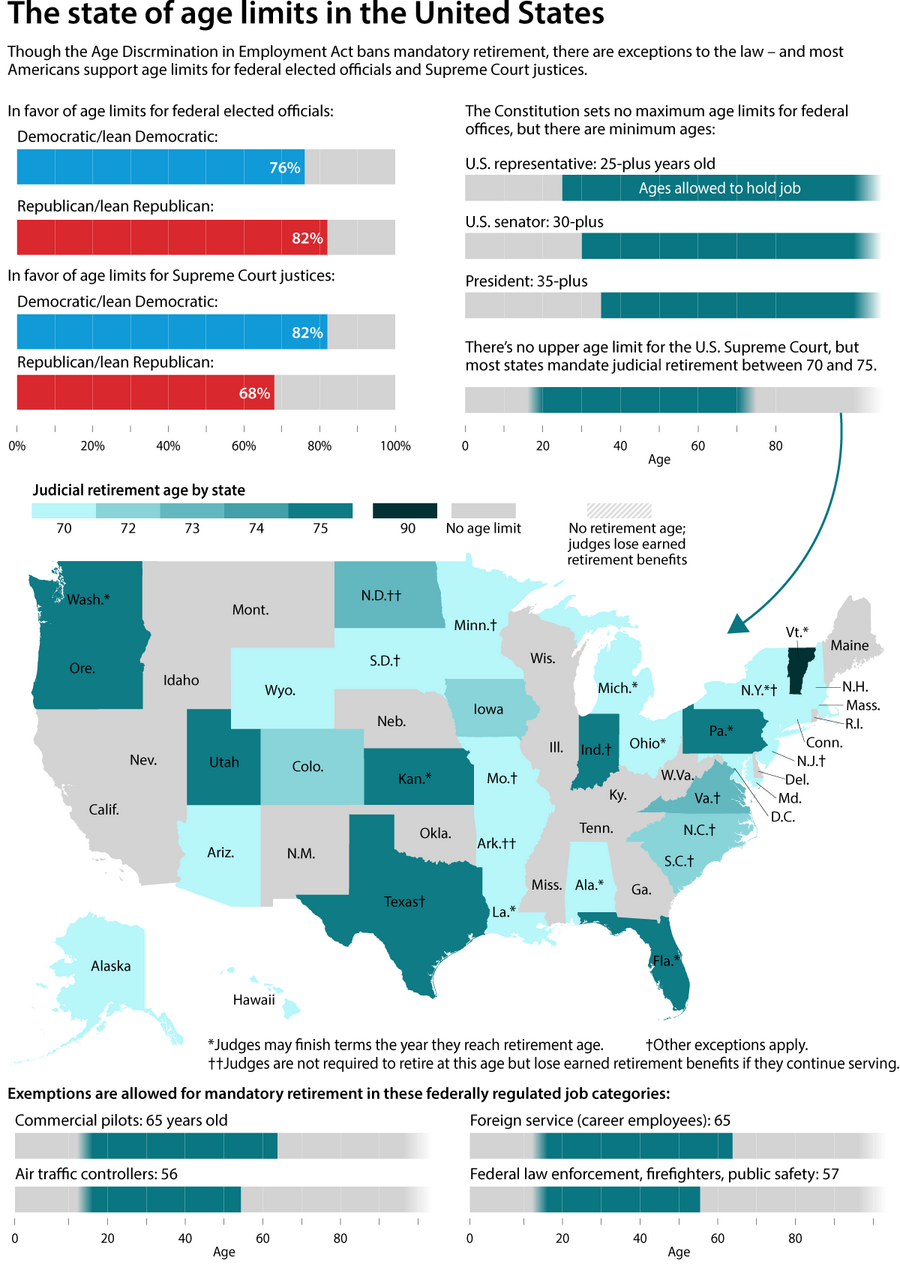

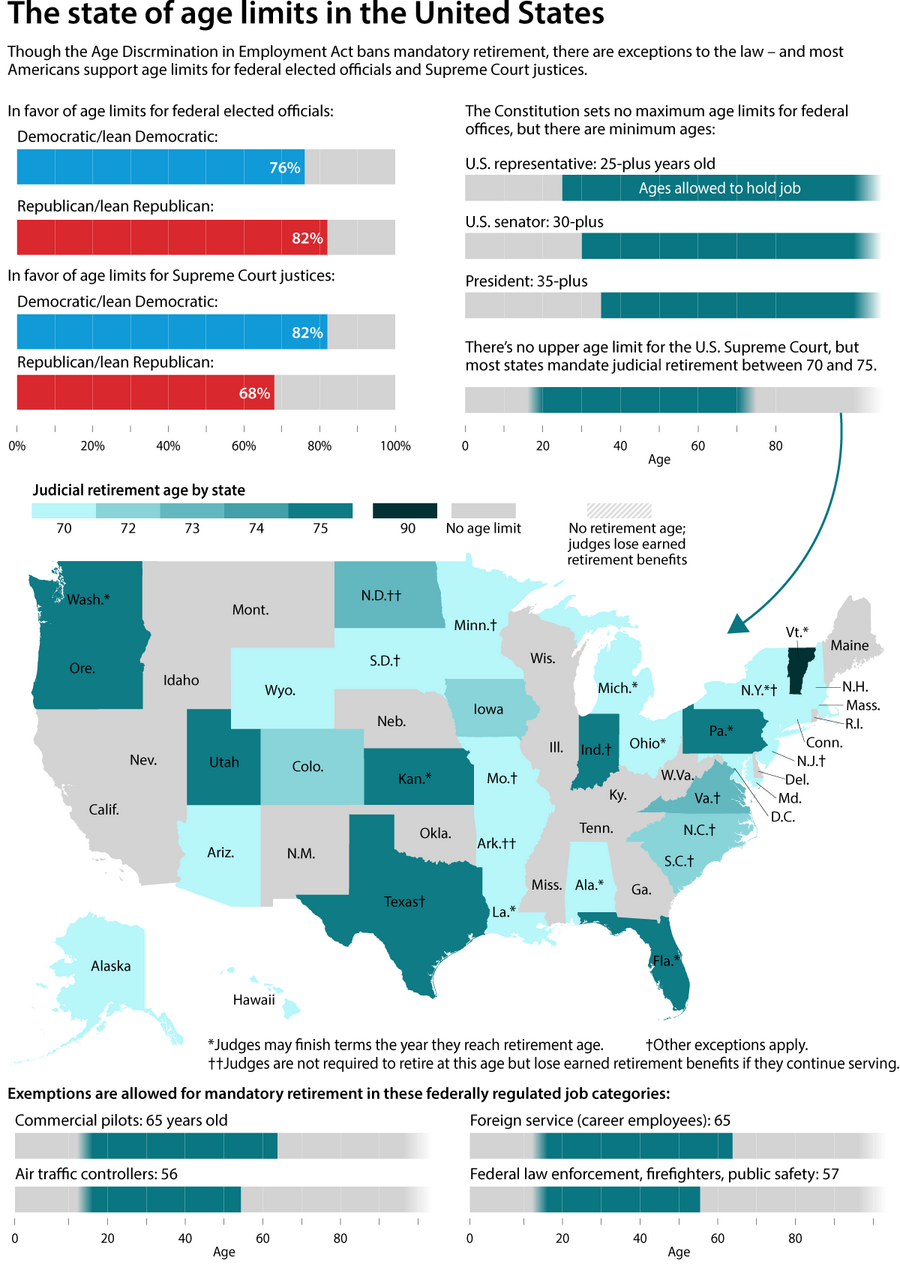

Pew Research Center, Ballotpedia, U.S. Justice Department, Bloomberg

A catalyst for deeper conversations

There is the possibility that Mr. Biden’s pullout, which he referred to as passing the torch “to a new generation ... new voices, fresh voices – yes, younger voices,” will give momentum to public policy efforts to define “too old.”

“Should we have age limits?” asks Steve Austad, a biologist and longevity researcher at the University of Alabama. “I don’t think so. Perhaps there are good reasons to have them, but they’re unfair to a lot of people.”

He adds, “I also don’t think it would be a bad national conversation to have ... as an opportunity to combat ageism.”

Dr. Austad says he was “intrigued” recently to discover one example of inconsistencies in age limits: There are mandatory retirement ages for judges in 32 states – and two states require forfeiture of retirement benefits if judges don’t retire at a certain age. But none of those states have mandatory retirement age limits for the legislators who set those limits.

Airing and clarifying what “too old” really means – or doesn’t – might raise consciousness about ageism’s societal effects, gerontologists say.

“Internalized ageism” in older people, says Dr. Carpenter, citing studies, “can change their behavior, their cognition, their physical activity, their willingness or desire to pursue certain things in life.”

Conversely, that research also shows that cultivating “positive age beliefs” can significantly change those effects.

Dr. Carpenter and his colleagues worry that ageist messages also influence the mindsets of younger people who, as they age, will also struggle with the gap between stereotypes and scientific facts about healthy aging.

“I am hopeful that maybe this will be a catalyst [that] will open the door to having more serious conversations about what ageism actually looks like and how it impacts us at all levels,” says Dr. Gendron.

This article was written with the support of a journalism fellowship from the Gerontological Society of America, the Journalists Network on Generations, and the Silver Century Foundation.

Pew Research Center, Ballotpedia, U.S. Justice Department, Bloomberg

Points of Progress

Senior housing that doesn’t isolate, and how community lifts Mexican women farmers

In our progress roundup, the meaning of community expands in senior living spaces when they are intentionally designed to be inviting to the public. And in Oaxaca, Mexico, women farmers who work for the benefit of the group are bringing an Indigenous practice to modern use.

Senior housing that doesn’t isolate, and how community lifts Mexican women farmers

Senior housing that encourages mixing of age groups is growing

Amenities like cafés that are open to the public bring benefits for residents and nonresidents alike. While 34% of older adults report feeling isolated, studies have shown that regular multigenerational interaction can reduce isolation, lessen depression, and combat ageism.

At North of Main Cafe in Bellevue, Washington, visitors can enjoy all of the typical features of a coffee shop – alongside seniors who live in the apartments above. In Calgary, Alberta, a government-funded pilot at a retirement home offered two discounted apartments to students.

Other spaces host cultural events for the public: The Watermark at Brooklyn Heights in New York features an art gallery and theater. One resident of The Watermark kick-started a summer swim camp after asking if grandchildren could use the pool.

Sources: Fast Company, Global News, University of Michigan

Indigenous Zapotec women learn techniques to conserve water, grow crops, and combat gender inequity

One community in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, measured a 90% corn crop loss last year. As the region faces increasing threats from climate change, women struggle to make ends meet while cultural mores leave them subordinate to men.

Following the Indigenous practice of tequio, in which individuals are obligated to assist their community, women work with the nonprofit Grupedsac to build 5,300-gallon ferro-cement tanks to collect and filter rainwater. The water is used for crops and household tasks.

Permaculture training has also helped the women become more self-sufficient, and lessons about gender and facilitated group therapy have proved empowering. “I now know my boys need to learn to cook, and help in the house,” said Aurora Perez.

Source: BBC

For the first time in nearly a decade, renewable energy firms are planning new U.K. wind farms

Parliament scrapped rules against new onshore wind farms in its National Planning Policy Framework. In 2015, a previous government had stipulated that turbine projects could be stopped by a single planning objection.

A trade association said that wind farms can take up to seven years to develop, but at least half a dozen developers are seeking sites for new farms. The new Labour Party government aims to reinvigorate efforts to double Britain’s onshore wind capacity by 2030. Onshore wind could enjoy more support than it did 10 years ago, owing to stronger financial incentives for communities and more efficient technology.

In April, the nonprofit Friends of the Earth found that England could produce enough energy to power every household 2.5 times more than currently required by devoting 3% of land to wind and solar power generation.

Source: The Guardian

Working with the ocean – instead of against it – to stave off beach erosion

"Sand motors" are artificial peninsulas that work by using millions of yards of dredged sand to extend a section of the shore out to sea. Over time, waves spread this sand across the coastline and replenish the beach. Though the upfront costs are higher, sand motors last much longer than the typical sand replenishment but aren’t suitable where erosion is more advanced.

“Beach nourishment” is particularly difficult on the Gulf of Guinea, where erosion rates are some of the highest in the world, governments lack the funds for upkeep, and coastal activities are a major driver of the economy. As part of the World Bank’s $594 million West Africa Coastal Areas Management Program, a sand motor built this year in Benin is modeled on the strategy first developed in the Netherlands. The Benin sand motor is near a river, with homes and hotels in between. But experts stress that when possible, communities should stop developing in low-lying areas.

Sources: Grist; World Bank; Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, South Holland

In Southeast Asia, cultural relevance is turning local movies into blockbusters

While Hollywood has been shaken by the pandemic and then by actors and writers strikes in 2023, films in countries such as Thailand have made millions by tapping into contemporary issues with cultural significance for audiences. Prior to the pandemic, Thai films accounted for 20% to 35% of the market share in the country; by June 2024, the percentage had shot up to 69%.

Across the region, viewers have flocked to theaters to see “How To Make Millions Before Grandma Dies.” The Thai film has made $9.1 million at home and become the most popular Thai movie of all time in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Audiences praise it for bridging the gap between younger and older generations and tackling complex subject matters such as poverty.

Other recent movies – such as the Vietnamese romance “Mai” and the Indonesian horror “KKN in Dancer’s Village” – have also broken box-office records.

Source: The Guardian

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Ending a war by embracing innocence

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Sometimes the worst wars start to end with the quiet acquiescence of their combatants. That may be the case now in Sudan where civilians have endured 16 months of a violent civil war.

Last week, talks to end the war began in Switzerland, but only one of the two warring factions showed up. By the weekend, however, each side had taken a critical step. The armed group attending the talks agreed to enable the delivery of emergency aid to parts of the East African country where hundreds of thousands of people are at risk of starvation. About the same time, and seemingly independently, the other faction opened a vital border crossing for the same purpose. The mutual acknowledgment of the need to protect innocent life may have opened a door to solving one of the world’s gravest crises.

Cultivating empathy among belligerents has opened new corridors for much-needed aid to Sudan’s distressed population. Its more enduring effect may be a lasting peace forged by a deeper valuing of innocence.

Ending a war by embracing innocence

Sometimes the worst wars start to end with the quiet acquiescence of their combatants. That may be the case now in Sudan where civilians have endured 16 months of a violent civil war.

Last week, talks to end the war began in Switzerland, but only one of the two warring factions showed up. By the weekend, however, each side had taken a critical step. The armed group attending the talks agreed to enable the delivery of emergency aid to parts of the East African country where hundreds of thousands of people are at risk of starvation. About the same time, and seemingly independently, the other faction opened a vital border crossing for the same purpose.

The mutual acknowledgment of the need to protect innocent life may have opened a door to solving one of the world’s gravest crises. The two sides, led by rival generals who once conspired to overthrow Sudan’s last civilian government, have now sent delegations for talks in Cairo on Tuesday – even as diplomacy continues in Geneva.

“These constructive decisions by both parties will enable the entry of aid needed to stop the famine, address food insecurity and respond to immense humanitarian needs,” international mediators in Geneva said in a joint statement.

The Cairo meeting is now “a crucial step in rebuilding trust and finding common ground between the warring parties,” the Arabian Post editorial board observed. “This latest effort could pave the way for a more stable and peaceful Sudan.”

International humanitarian law is anchored by the Fourth Geneva Convention, which requires that in warfare, “persons taking no active part in the hostilities ... shall in all circumstances be treated humanely.” Recent trends in conflict resolution, the International Committee of the Red Cross noted, have shown that protecting innocent civilians from harm “can have an impact on the success of peace negotiations and agreements, as well as on the chances for post-conflict reconciliation.”

Humanitarian gestures, the ICRC observed, helped the Colombian government build trust with guerrilla factions and strengthen compliance with a 2016 peace accord. More recently, two armed groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo signed a mutual pledge in March to respect and protect civilians caught in the vast African country’s fragmented wars. The agreement followed training courses led by international humanitarian experts. As the leaders of one of the factions told The Associated Press, “Now, we feel – we can see – there’s a change on the ground, and so we can’t let ourselves do whatever we want anymore.”

Since the outbreak of the civil war in Sudan in April 2023, humanitarian aid workers and international peace groups have sought to reduce the use of sexual violence, recruitment of child soldiers, and starvation as tools of war by educating armed groups in humanitarian law. Such efforts reinforce that harming civilians should not be dismissed as “mere unintended consequences of war,” said Christina Markus Lassen, Denmark’s representative to the United Nations Security Council, in a debate on Sudan in May.

Cultivating empathy among belligerents has opened new corridors for much-needed aid to Sudan’s distressed population. Its more enduring effect may be a lasting peace forged by a deeper valuing of innocence.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Life’s promise of continued capability

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Valerie Minard

Recognizing that God’s children are never doomed to decrepitude frees us from age-related limitations, as a woman experienced after she was faced with knee problems.

Life’s promise of continued capability

Age has been a hot topic in the news lately. Many are asking at what point age affects one’s physical and mental health and capabilities. An acquaintance mentioned that this even led her to question her own usefulness and self-worth in society as she grew older.

In thinking about the topic of aging, what’s curious to me is that the Bible records Moses going to free the Israelites from Egyptian slavery at 80 years old. He then gave them the Ten Commandments and guided them throughout their 40-year journey to the promised land. The Bible says that “his eye was not dim, nor his natural force abated” (Deuteronomy 34:7). His siblings accompanied him, too. Clearly, those three didn’t let age limit them or their mission!

Mary Baker Eddy, who founded the Pulitzer Prize-winning Christian Science Monitor when she was 87, wrote in her seminal work, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” “Chronological data are no part of the vast forever. Time-tables of birth and death are so many conspiracies against manhood and womanhood. Except for the error of measuring and limiting all that is good and beautiful, man would enjoy more than threescore years and ten and still maintain his vigor, freshness, and promise. Man, governed by immortal Mind, is always beautiful and grand. Each succeeding year unfolds wisdom, beauty, and holiness” (p. 246).

I love the idea of life growing in vigor, freshness, and promise with each succeeding year! God, infinite Life itself, doesn’t have an expiration date. As the spiritual idea, or offspring, of God, man – a term that includes everyone – is always governed by the divine Mind. As we identify ourselves and others through this spiritual lens, rather than as degenerating mortals, we realize more and more the promise of expressing greater abilities and goodness.

These ideas were helpful when I faced a problem with my knees. Climbing stairs had become difficult. I’d had other healings through Christian Science prayer in the past, so I had confidence this could be met with such prayer as well.

I realized that I had taken in the notion that joint problems, and even replacements, are inevitable as one ages. But as I prayed I was inspired by the idea that the only thing I needed to replace was the lie that I was a vulnerable mortal at the mercy of time.

Christian Science teaches that God is Life and is eternal. Our true identity as the spiritual reflection of this eternal Life isn’t governed by body parts with expiration dates. Instead of rolling over and accepting decrepitude as unavoidable, I affirmed that divine Mind, God, good, is the only true cause – the source of all action.

I also prayed with the Bible verse that says, “It is written, As I live, saith the Lord, every knee shall bow to me” (Romans 14:11). I thought of “bowing” as “bending” and loved the idea that this was a divine command and promise, and so it must be fulfilled, because God knew my “downsitting and mine uprising” (Psalms 139:2). That is, He knew me as He created me – spiritual, capable, and free.

Then I was scheduled to serve a two-week stint as a Christian Science practitioner at a Christian Science camp. Not only was it an active group of campers, but also, it turned out that my room assignment was on the top floor of the dining hall. Every time I went up the stairs, I prayed. The Bible says that we are “joint-heirs with Christ” (Romans 8:17). Our heritage from God, Spirit, is pure goodness.

By the end of the two weeks, I had complete mobility. The thoroughness of the healing was further proven a couple of weeks later, when I was able to climb the 100-plus stairs at a beach every day for a week, without pain. And in some cases I did it without even needing to sit down for a rest. That was over a year ago, and the problem hasn’t returned.

We don’t need to accept age-related, limiting beliefs that our God-given capability can be undermined. Divine Life is eternal and is forever maintaining our “wisdom, beauty, and holiness.” And that’s a promise!

Viewfinder

‘Once in a ...’

A look ahead

We’re so glad you could join us today. As part of our continuing coverage of the Democratic convention in the United States, tomorrow we’ll check on vice presidential candidate Tim Walz. Two weeks after his selection, how is his addition affecting the Democratic presidential ticket?