- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 10 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- How would Kamala Harris govern? Her past career offers signals.

- Today’s news briefs

- What do Jewish and Palestinian Israelis have in common? Hope.

- Tornadoes are swirling in unusual places. Why twisters are shifting east.

- In rural India, ‘goat nurses’ help animals – and themselves

- The ‘other’ Alaska cruise: Got a week? Pitch your tent on deck.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Investigative journalism, Monitor style

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

Investigative journalism is one of the media’s most powerful tools. The Monitor has done its share. But we also offer a twist.

Read today’s story by Dina Kraft about Israeli Jews and Palestinians coming together to fight for one another’s humanity and safety. Ask yourself: Have I seen anything like that anywhere else? Other news outlets often ignore such stories or cordon them off as “good news.”

We know they are much more. They are the seeds of a different future, and they could not be more important. We might have to dig a bit to find them. But that’s a different – and equally important – kind of investigative journalism.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

A deeper look

How would Kamala Harris govern? Her past career offers signals.

This year’s U.S. presidential campaign is light on policy details. For hints of what Kamala Harris might do as president, we look at her track record in public office.

Kamala Harris has spent nearly her entire career working in government. Viewed by many as a rising star from the outset, she moved from the District Attorney’s Office in San Francisco to state attorney general. She won a U.S. Senate seat on her first try, and just four years later was tapped as President Joe Biden’s second in command.

When Ms. Harris ran for district attorney in 2003, she campaigned to the right of the incumbent (her former boss), promising higher conviction rates and better relations with police.

She also wanted to reduce the number of repeat offenders. Citing statistics that most incarcerated people were high school dropouts, as district attorney she created a truancy court that held parents accountable for school attendance. Between 2005 and 2009, habitual absences at elementary schools dropped by half.

“She was both tough on crime and tried to prevent crime, and that’s where you really want to be,” says former California Sen. Barbara Boxer.

Asked to characterize her record over the course of her 20 years in public office, longtime political observer John Pitney sums it up this way: “progressive, but not radical.”

How would Kamala Harris govern? Her past career offers signals.

Kamala Harris has spent nearly her entire career working in government. Viewed by many as a rising star from the outset, she moved doggedly from the District Attorney’s Office in San Francisco to state attorney general. She won a U.S. Senate seat on her first try, and just four years later was tapped as President Joe Biden’s second in command.

Asked to characterize her record over the course of her 20 years in public office, longtime political observer John Pitney sums it up this way: “progressive, but not radical.” In many ways, he says, a Harris presidency would probably look a lot like an extension of the Biden presidency. “If you like what Joe Biden tried to do, you’ll like what Kamala Harris tries to do,” says Dr. Pitney, a professor of politics at Claremont McKenna College in California.

Harris and the California years: “smart on crime”?

When Ms. Harris ran for district attorney in 2003, the San Francisco Chronicle ran this headline in its endorsement: “Harris, for Law and Order.” She campaigned to the right of the incumbent (her former boss), promising higher conviction rates, higher prosecution of drug crimes, and better relations with police. She later touted a felony conviction rate far higher than her predecessor’s.

The goal of reducing recidivism

She also wanted to reduce the number of repeat offenders. As district attorney, she started a diversion program for first-time, nonviolent offenders in low-level drug sales. Fewer than 10% of graduates from the Back on Track program reoffended. Citing statistics that most incarcerated people were high school dropouts, she created a truancy court that held parents accountable for school attendance. Between 2005 and 2009, habitual absences at elementary schools dropped by half.

“She was both tough on crime and tried to prevent crime, and that’s where you really want to be,” says former California Sen. Barbara Boxer.

Opposition to death penalty

Ms. Harris outlined her approach in a book, “Smart on Crime.” But her staunch opposition to the death penalty drew sharp criticism when a man shot and killed a San Francisco police officer. At the officer’s funeral in 2004, California Sen. Dianne Feinstein drew a standing ovation when she said the case warranted the death penalty. Ms. Harris sat in a front pew. She did not change her mind.

After a squeaker election in 2010, Ms. Harris became attorney general. She is often described as “careful” in that job, eyeing higher political office. Unlike previous attorneys general, she refused to take positions on ballot measures.

Addressing a foreclosure wave and consumer issues

She talks today about going after for-profit colleges and big banks when she was California attorney general. The mortgage foreclosure crisis defined her six-year tenure.

“She did not burnish herself as a ‘top cop’ but more as an attorney general on consumer issues,” says Rob Stutzman, a California Republican strategist who does not support Donald Trump.

The Great Recession was still reverberating in California when Ms. Harris became attorney general in 2011. Nearly a third of homeowners were underwater, owing more on their homes than they were worth. More than 10% were seriously delinquent on mortgages.

In a high-risk move, she broke with negotiations that the Obama administration was carrying out with the nation’s five largest banks over predatory lending practices. The hardball tactics paid off. She substantially increased California’s take, winning a $20 billion settlement to help Golden State homeowners. She also pushed a homeowners’ “bill of rights” through the state Legislature.

She also took on the tech industry in a sprawling case against a now-defunct sex advertising internet site, Backpage.com, the leading online venue for prostitution ads – some of which trafficked minors. The site operated in 50 states, but Ms. Harris was the first state attorney general to bring a criminal case.

Senator Harris: the anti-Trump

Ms. Harris was elected to the U.S. Senate in 2016, the same year voters sent Mr. Trump to the White House. Like Barack Obama, she ran for president before finishing her first term.

The nonpartisan GovTrack ranked her as the fourth-most-left senator during her time in office, based on bills sponsored and co-sponsored. But with Democrats in the minority, she didn’t have much legislative impact.

Ms. Harris churned out more than 130 bills and resolutions; only four became law. Her bills reflected her interests: legal representation for detained unauthorized immigrants, inclusion of gender identity and sexual orientation in the census, a tax credit for overburdened renters, aid for working parents by helping elementary schools stay open longer. A version of her bill defining lynching as a federal hate crime was eventually signed into law, in a slightly different form.

An interest in moms and health care

As vice president, she later brought some of these ideas to the White House. A monthly child tax credit became part of the American Rescue Plan, and the Build Back Better Act included provisions to improve maternal and infant health – particularly for people of color.

No vice president had ever emphasized this maternal health issue, says Dan Morain, a longtime California journalist and author of the book “Kamala’s Way: An American Life.” “It’s not a big war-and-peace-type issue, but it is of vital importance to moms and their babies.”

At hearings, a prosecutor’s zeal on display

Much of the attention Ms. Harris attracted during her time in the Senate came from her white-hot grilling of administration nominees and officials at hearings.

In 2017, she relentlessly pressed then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions when he appeared before the Senate Intelligence Committee. Under her rapid-fire questioning about whether he had met with Russian intelligence at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Mr. Sessions stammered, “I’m not able to be rushed this fast. It makes me nervous.”

At Brett Kavanaugh’s explosive Supreme Court nomination hearing in 2018, she seemed to catch him off guard when she asked, “Can you think of any laws that give the government the power to make decisions about the male body?” His answer: “I’m not – I’m not – I’m not thinking of any right now, senator.”

“I remember thinking at the time that it was almost painstakingly scripted to be a precampaign type of moment for her,” says Mr. Stutzman, the GOP consultant.

Role as vice president

As vice president, Ms. Harris got off to a rough start. She took office during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, which limited her events and travel. Uncertainty about her boss’s future plans – will he or won’t he run for reelection? – created ambiguity about her own trajectory. And President Biden, unlike Mr. Trump, Mr. Obama, and George W. Bush, didn’t need his vice president to take the lead on Capitol Hill or diplomatic affairs. He had a Washington résumé a mile long.

“Harder than being a vice president is being the vice president to a former vice president,” writes Franklin Foer in his book “The Last Politician,” about the Biden presidency.

Problems soon arose within her office: high staff turnover, complaints about her being a tough boss, an indeterminate portfolio – troubles that had dogged her earlier campaign for the presidency. She also had awkward interactions with the media, including a 2021 interview with NBC’s Lester Holt on immigration.

Eventually, things improved. She grew more comfortable in her role as loyal administration messenger, adjunct diplomat, and behind-the-scenes adviser. She became an effective megaphone on women’s reproductive rights. She delivered important security messages to European leaders. She quietly nudged the president toward choosing Ketanji Brown Jackson as his Supreme Court nominee.

From the beginning, President Biden made clear he wanted her in on meetings and decisions. That’s invaluable on-the-job training for a promotion, should she get it.

But as a vice president-turned-candidate, “You carry the administration’s baggage,” says Joel Goldstein, an expert on the vice presidency and professor emeritus at St. Louis University School of Law. In this case, that includes a painful surge of inflation, record illegal immigration, and the botched exit of U.S. troops from Afghanistan. But Ms. Harris can also point to the pandemic recovery, robust job and economic growth, a bipartisan infrastructure deal, and help for older adults on prescription drug costs.

On balance, “She’s had a consequential vice presidency,” argues Professor Goldstein, not least because of her barrier-breaking gender and race as the daughter of a mother from India and father from Jamaica.

On the other hand, Mr. Stutzman describes Ms. Harris as a “standard VP that was a bit of a do-nothing.” She never clearly defined her role, he says, so Republicans were able to define it for her, negatively.

As vice president, Ms. Harris took on roles in several key areas:

She’s the Senate tiebreaker

In her constitutional role as Senate president, Ms. Harris broke 33 tie votes – more than any vice president ever, and a function of the evenly split Senate during her first two years. Most of those votes were to advance presidential nominees. But she also put two big bills over the finish line: the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

The ARP was Congress’ second round of pandemic relief. One year earlier, a first round had passed with near unanimity under President Trump. But this time Republicans balked, warning that the $1.9 trillion stimulus would be inflationary. They made the same argument against the IRA, a catchall bill that included many progressive priorities such as lower prices for prescription drugs for older people and the largest-ever investment in clean energy.

On immigration, seeking root causes of a border crisis

Illegal crossings began to spike soon after President Biden took office in January 2021. That spring, he tasked Ms. Harris with tackling the root causes of migration from northern Central America. It was a thankless assignment – a long-term solution for a problem that was making daily headlines.

In Guatemala that June, where she bluntly warned migrants, “Do not come,” Ms. Harris sat for an interview with Mr. Holt. Asked if she planned to visit the border, she answered, “We’ve been to the border.” And when he noted that she hadn’t been there, she retorted defensively, “And I haven’t been to Europe.”

The interview was “a problem of her own making,” says Mr. Morain, the biographer.

For her “root causes” effort, Ms. Harris focused on boosting private investment in the region. That generated $5 billion in pledges from such corporations as Visa, Nestlé, and Meta. So far, just over $1 billion has reached its destination. Still, under the Biden administration, the Border Patrol has had more than 7 million encounters with unauthorized migrants at the southern border. That’s more than triple the amount under Mr. Trump – though encounters have dropped significantly in recent months.

In response to GOP attacks, Ms. Harris has been trying to present herself as “tough” on the border. She emphasizes her record as a former border-state attorney general who took on cartels smuggling guns, drugs, and people. She’s also hit back at President Trump for

directing Republicans to kill a bipartisan border security bill, which she says she would sign.

Active role on foreign policy and diplomacy

President Biden showed confidence in his No. 2 by sending her to meet with key leaders and attend important international forums in Europe and Asia. “It’s not like she’s being sent off to Liechtenstein,” notes Professor Goldstein.

She was dispatched to Paris to patch up relations over a disputed submarine deal. She traveled to Southeast Asia to strengthen ties as a counterbalance to China. Three times, Mr. Biden sent Ms. Harris to the Munich Security Conference – his milieu.

Around the 2022 conference, she met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and shared U.S. intelligence about a pending invasion. “I’m not convinced,” he said, as reported in Mr. Foer’s book. “All I can do is state the facts,” she replied. Days later, Russia invaded.

On the divisive issue of the war in Gaza, she’s given greater rhetorical weight to Palestinian victims, but has not deviated from the administration’s position. That means strong support for Israel, including arms, as well as the need for a cease-fire and a two-state solution. She also supports deep empathy for those in Gaza where she says, “The scale of suffering is heartbreaking.”

A voice for the administration on abortion rights – and more

After the Supreme Court overturned the national right to an abortion in 2022, Ms. Harris became the administration’s champion for reproductive rights. She went to Florida to deliver an impassioned speech on the 50th anniversary of Roe v. Wade, visited a Planned Parenthood clinic (a first for any president or vice president), and has met with dozens of state leaders and legislators to discuss abortion access.

“She had a bully pulpit; she used it,” says Mr. Morain.

She was also tasked with amplifying administration messages on infrastructure, climate change, and gun violence. After Congress passed bipartisan gun legislation in 2022, President Biden created the White House Office of Gun Violence Prevention and put Ms. Harris, who supports a ban on assault weapons, in charge of it. Since the administration implemented a zero-violations policy for gun licensees in 2021, more than 420 gun dealers have been closed for violations.

“Don’t underestimate her,” Mr. Morain says of Ms. Harris. “I’ve written that a bunch of times.”

Staff writer Linda Feldmann contributed to this story.

Also see our parallel story on Donald Trump's record, from taxes and trade to immigration and the judiciary.

Today’s news briefs

• China missile test: In a rare test, China has fired an intercontinental ballistic missile into the Pacific Ocean, adding to tensions in the region where multiple countries have overlapping territorial claims.

• U.S. death row executions: People on death row in five states are set to be put to death in the span of one week. If carried out as planned, the executions will mark the first time in more than 20 years that five executions were held in seven days.

• Thailand same-sex marriage: Thailand’s landmark marriage equality bill was officially written into law, allowing same-sex couples to legally wed.

• Haitian community charges: The leader of a nonprofit representing the Haitian community has invoked a private-citizen right to file charges against former President Donald Trump and his running mate, JD Vance, over the threats experienced by Springfield, Ohio.

What do Jewish and Palestinian Israelis have in common? Hope.

A group uniting Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel is enjoying unexpected success with its message of a shared home. The alternative, says one founder of Standing Together, is “ongoing slaughter.”

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

At a time when Israel is living through the most significant crisis in its history, fighting a war in Gaza and a near-war in Lebanon, it is perhaps surprising that an organization promoting unity between Jewish and Palestinian Israelis is flourishing.

But Standing Together is attracting record numbers of new members in Israel with its simple and direct calls for peace, and its belief that Israeli-Palestinian partnership, starting within Israel, is not just aspirational, but essential.

The organization’s view of Israel as a shared home, where Jewish and Palestinian citizens share common interests, is central to its work. Before the war broke out in Gaza, Standing Together concerned itself with social and economic justice issues. Since Oct. 7, it has pivoted its mission to fighting for what can feel like a radical notion these days: peace itself.

That fight takes different forms. Some members have been elected to municipal councils. Others accompany aid convoys into Gaza, protecting them from far-right activists trying to block the assistance.

What they have in common is hope, says Dani Filc, a founder of Standing Together. “We struggle because we did not lose hope,” he says. “Hope is mandatory, because the alternative is ongoing slaughter.”

What do Jewish and Palestinian Israelis have in common? Hope.

Dusk has fallen over a major Tel Aviv intersection, now shut off to traffic and packed with protesters calling on the Israeli government to strike a deal that would free the country’s hostages from Hamas captivity.

A young woman, her dark hair fastened with a purple kerchief, rallies her comrades, struggling to make herself heard above the din of megaphone-led chants, drumming, and horns.

“Okay, now!” she shouts. “Hoist it now.”

Together, arms over their heads, they unfurl a 100-foot-long banner that reads, “So that they may all come home: Withdraw from Gaza.”

That demand is unusual among the sea of placards, chants, and signs on display at the demonstration; it acknowledges Palestinian suffering in the Gaza Strip at the hands of the Israeli military, as well as the hostages’ ordeal.

And it comes from an unusual source – a grassroots movement called Standing Together, created jointly by Jewish and Palestinian Israelis, whose members are recognizable by their purple shirts and signs.

Surprisingly, at a time when Israel is undergoing the most significant crisis in its history, the organization, founded in 2015, is enjoying a growth spurt. It is attracting record numbers of new members with its simple and direct calls for peace and its belief that Israeli-Palestinian partnership, starting within Israel, is not just aspirational, but essential.

“We are [all] losing from the current reality, and more than that, we can all win if the reality would be better for all of us. We can all win when there will be safety for everyone … when every person of this land will be equal and free,” says Alon-Lee Green, the Jewish Israeli co-director of Standing Together.

These ideas can be difficult to hold on to, he says, “at a time that is so polarizing and pushing people to extremes.”

Israel as a shared home to Jews and Palestinians?

Standing Together’s view of Israel as a shared home, where Jewish and Palestinian citizens unite in common interests, is central to its work. The group says it is trying to promote an alternative view to the narrative that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has imposed for the past three decades – that there is no solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, only “managing” it.

As the war in Gaza grinds on, and violence on the Lebanese border threatens to spill over into full-scale war, “we are currently in an emergency situation,” says Rula Daood, the Palestinian Israeli co-director of Standing Together. “Thousands of citizens, Jewish and Arabs, are in shelters and don’t know what will happen next.”

Until the brutal Hamas assault on Israel on Oct. 7, Standing Together concerned itself with social and economic justice issues such as affordable housing and protesting against Israel’s occupation of the West Bank. Since the war began, it has pivoted its mission to fighting for what can feel like a radical notion these days: peace itself.

That fight can take different forms.

The group attracted overflow crowds to its Jewish-Arab solidarity conventions in the weeks after Oct.7. Its smaller, more intimate dialogue-style gatherings are popular, and some members have won seats on municipal councils.

But the action can also get more robust. Earlier this year, when far-right activists disrupted an aid convoy headed to Gaza, tossing food off the trucks and setting fire to two vehicles, Standing Together activists confronted them. Forming what they called a “humanitarian guard,” they protected subsequent convoys, ensuring their aid was delivered.

In August, the organization arranged for a truck to drive among Arab towns in Israel to collect aid supplies for delivery to Gaza. The volunteer response, most of it from Palestinian Israelis relieved to be able to help Gazan civilians, was overwhelming. Thousands of people donated goods, and ultimately some 400 truckloads of supplies were collected.

“People felt secure to come to one point, not just to donate food and hygienic stuff, but also to take part, to be part of what was happening, to feel that they have something that they can contribute,” says Ms. Daood.

Among the Jewish Standing Together activists who joined them was Haviva Ner-David, who lives in the Galilee and whose chapter has doubled to 700 members in the past year. What made the Gaza aid drive more moving, she says, “was that we were doing this together — Palestinian and Jewish Israelis of all ages, including children, the elderly, and the physically challenged, even amid a war between our nations.”

A fresh perspective, or ‘ongoing slaughter’

Ms. Daood says it was during a Standing Together march in Tel Aviv in 2017, filled with the unusual sound of both Hebrew and Arabic chants against racism, that she first felt the pull and the power of a shared voice.

“That moment felt so huge for me; it made me realize that partnership is something that you can just do,” she says.

That kind of partnership also offers a fresh perspective, suggests Dani Filc, a professor of politics and government at Ben-Gurion University who helped found Standing Together.

“We are always conscious of not taking a moralist stand,” he says. “We are opposing the war in the interests of all Israelis, both Jewish and Palestinians, not playing a blame game.”

“One of the main slogans of the movement is ‘Where there is struggle, there is hope,’” Professor Filc points out. “And we struggle because we did not lose hope. Hope is mandatory, because the alternative is ongoing slaughter.”

The Explainer

Tornadoes are swirling in unusual places. Why twisters are shifting east.

Research suggests tornado patterns in the United States are changing, as twisters arrive later in the year and land farther east. We explore factors behind the trend and what residents can do to be ready.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Tornadoes are touching down across the United States in seemingly unusual places, from Virginia to Michigan. On Sunday, tornadoes damaged buildings in Indiana, and forecasters see a risk of more this week linked to the expected Hurricane Helene in the Southeast.

But these events outside Tornado Alley – the Great Plains region known for its massive, slow-moving twisters – might not be as atypical as they seem.

Researchers suggest that the shift might represent a larger trend, with a recent study finding that the number of tornadoes is decreasing in the Great Plains while increasing elsewhere in the Midwest and in the Southeast.

The timing has also changed. Tornadoes outside the Great Plains tend to occur in the fall and winter, rather than in the summer. So that means that the eastward trend in the most tornado-prone regions of the U.S. is also accompanied by a shift in the season in which tornadoes are occurring.

The cause of the shift is difficult to pinpoint, and could be related to climate change or oscillations in the ocean, says Tim Coleman, director of forensic meteorology at WeatherBell Analytics.

Tornadoes are swirling in unusual places. Why twisters are shifting east.

Tornadoes are touching down across the United States in seemingly unusual places, from Virginia to Michigan. On Sunday, tornadoes damaged buildings in Indiana, and forecasters see a risk of more this week linked to the expected Hurricane Helene in the Southeast.

But these events outside Tornado Alley – the Great Plains region known for its massive, slow-moving twisters – might not be as atypical as they seem.

Researchers suggest that the shift might represent a larger trend, with a recent study finding that the number of tornadoes is decreasing in the Great Plains while increasing elsewhere in the Midwest and in the Southeast.

Why are tornadoes moving east?

The cause of the shift is difficult to pinpoint, says Tim Coleman, director of forensic meteorology at WeatherBell Analytics and lead author of a study on shifts in tornado activity published in June in the Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.

“It could be related to climate change,” he says. “We don’t prove or disprove that. It could also be related to these regular multidecadal oscillations in the ocean, and it could be something else. We don’t know.”

Grady Dixon, a meteorologist and climatologist, says climate change might be behind the geographical shift. He notes that the shift in tornadoes has been coupled with fewer tornado days but more tornadoes on each day. “That pattern of ‘fewer but bigger’ events seems to be common in other climate change-fueled weather patterns,” says Dr. Dixon, also a professor at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas. “It fits the model.”

Understanding changes in tornado patterns is difficult because tornado formation and tornado reports are dependent on a number of complex and variable factors.

Tornado formation is a product of moist air, an unstable atmosphere, and wind shear, meaning changes in wind speed over a short distance. As global temperatures rise, the amount of moisture within the atmosphere is likely to increase, but wind shear might decrease, making it difficult for scientists to discern a link between climate change and tornado formation.

Reaching solid conclusions about tornadoes’ relationship to climate change is also difficult because of changes in tornado reporting and monitoring methods, which have improved since the advent of mobile phones, high-quality cameras, and social media. “A farmer might have seen a tornado decades ago and went home and told his family about it and never thought about it again,” Dr. Dixon says. “Now, without even taking his hand off the steering wheel of the combine, he’s broadcasting that to the world.”

What else is changing about tornadoes?

Despite difficulties in confidently connecting the change in tornadoes to rising global temperatures, some researchers argue it’s worth noting that the shifts closely follow changes in other major weather patterns that have been linked to global warming. For example, some scientists have pointed to both a potential decrease in the frequency of Atlantic hurricanes and an increase in the most intense storms.

Similarly, the number of tornadoes in a year has remained relatively constant, but tornadoes are now more likely to occur in outbreaks rather than be spread throughout the year.

The timing has also changed. Tornadoes outside the Great Plains tend to occur in the fall and winter, rather than in the summer. So that means that the eastward trend in the most tornado-prone regions of the U.S. is also accompanied by a shift in the season in which tornadoes are occurring.

“We’re seeing fewer spring and summer tornadoes and more fall and winter tornadoes,” Dr. Coleman says.

Tornadoes elsewhere in the Midwest and in the Southeast are also often deadlier than those in the Great Plains, says Harold Brooks, a senior research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This is because of higher population densities, higher rates of poverty, and more mobile homes, he says.

Meteorologists agree that makes warning systems all the more important.

How can residents prepare?

The shift in tornado activity brings new challenges for regions unaccustomed to frequent tornadoes. Still, tornadoes are survivable – and simple safety precautions can greatly increase security.

In the moment, it’s important for residents to understand the three kinds of tornado alerts issued by the National Weather Service: tornado watches, tornado warnings, and tornado emergencies.

A tornado watch suggests tornadoes are possible within the area, based on weather conditions. Those who receive the alert should keep an eye on the weather, consider postponing outdoor activities, and be prepared to seek shelter.

On the other hand, a tornado warning indicates that a tornado has been sighted, while a tornado emergency alert indicates a violent tornado has touched down in the area. In both cases, individuals should seek shelter immediately, moving to the lowest floor of a sturdy building and as far from windows as possible, experts say. Residents of mobile homes should evacuate as soon as possible, moving to a preidentified location – ideally a strongly grounded building with a basement.

Those in vehicles at the time of receiving the tornado warning or tornado emergency alert should attempt to find a solid building in which to take shelter. If that’s not possible, drivers and passengers should consider lying flat in a nearby ditch or taking cover in their stationary vehicle with seat belts buckled and a jacket or blanket covering their arms, neck, and head.

Nobody should attempt to outdrive a tornado, experts say. Instead, shelter in place.

Before any tornado alert, residents should reach out to their local National Weather Services office or TV meteorologist, or a nearby university for help developing a plan that works for their specific conditions, Dr. Dixon says.

“They need to have a plan when they have just two minutes to react, and they need to have a plan when they have 30 minutes or more to react,” he says.

In the long term, homeowners can also look to add hurricane clips to their rafters or fortify walk-in closets to use as tornado shelters, adds Dr. Brooks.

In rural India, ‘goat nurses’ help animals – and themselves

In rural India, a goat is a valuable asset. For the women who have been trained to care for them, they’re also a path to greater dignity and respect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

India is home to one-sixth of the world’s goat population. Although these creatures can be a critical source of income for families, poor access to veterinary services and owners’ limited knowledge of animal health led to high mortality and morbidity rates.

But results from one novel initiative indicate the tide may be turning.

The Pashu Sakhi, or “friend of the animal,” program works to fill gaps in veterinary care by transforming rural, semiliterate women into animal health care workers. With support from the Indian government, around 60,000 women across India have been trained to respond to medical emergencies and provide services like deworming and vaccination, leading to a spurt in goat populations in several states, say program coordinators.

Goat mortality in the Jharkhand, for example, was once 50%; authorities now report that figure is below 15%.

Livestock owners pay a fixed sum for each service, and “goat nurses” also receive a small stipend from the government. But there’s a less tangible outcome, too – the building up of women’s self-esteem and independence.

Basmati Devi says that being a wife was once her only identity. “People used to know me by my husband’s name,” she says. “Now they know me as a goat nurse, and it feels good.”

In rural India, ‘goat nurses’ help animals – and themselves

Dressed in a light-blue sari, Ritmani Devi cradles two black baby goats as she guides a flock of ducks toward its coop. The birds scurry between the legs of an older goat, quacking nonstop.

A few years ago, this muddy yard was much less lively. Ritmani Devi’s goats would often die, she says, and the ones that survived weren’t very healthy. This was common here in the east Indian state of Jharkhand and throughout the country.

India is home to one-sixth of the world’s goat population. A goat is a valuable asset for a low-income family, ready to be sold at a moment’s notice in case of emergencies. But with owners lacking basic animal health knowledge, that’s all they were – a one-time, last-ditch safety net, rather than an alternative stream of income. Plus, poor access to veterinary services led to high mortality and morbidity rates among goats.

Now, results from one novel initiative that began a decade ago indicate the tide may be turning. The Pashu Sakhi, or “friend of the animal,” program works to fill gaps in veterinary care by transforming rural, semiliterate women into community animal health care workers, or “goat nurses.” With support from the Indian government, the World Bank, the Gates Foundation, and others, around 60,000 women across India have been trained to provide services like vaccination and deworming, leading to a spurt in goat populations in several states. They are paid for the care they provide, and gain a sense of pride and independence.

For Basmati Devi – who is not related to Ritmani Devi, but like many women in Jharkhand uses Devi (meaning “goddess”) like a surname – being a wife was once her only identity. “People used to know me by my husband’s name,” she says. “Now they know me as a goat nurse, and it feels good.”

Goat nurses to the rescue

At the community hall near Ritmani Devi’s home in Getalsud village, the walls are painted with training material, including illustrations of common symptoms to look out for, like swelling under the animal’s mouth or pale eyes, and tips on how to negotiate better rates for goats in the market.

Jharkhand was one of the first states in India to adopt the Pashu Sakhi model. Having women at the forefront of the initiative was a natural choice, says Swadesh Singh, a livestock specialist at the Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society, the government agency that runs the program.

In rural India, the responsibility of managing small ruminants and poultry usually falls on women. Meanwhile, veterinary doctors – who sometimes serve multiple village clusters alone – focus on larger, more valuable animals like cows and buffalo. Before the program, goat mortality in Jharkhand was 50%, says Dr. Singh.

Authorities say that figure is now below 15% – thanks in large part to the state’s goat nurses.

The typical Pashu Sakhi candidate has at least eight years of schooling. After being selected by the state’s livestock department, they’re taught how to administer vaccines, what type of fodder is best for the animals, and how to give preventative care. More advanced nurses also get trained in managing disease, performing castration, goat breeding and marketing, and more.

Goat nurses are often the first responders in any livestock-related medical emergency, in addition to conducting regular check-ups and advising others on goat rearing. Their proximity is a huge advantage. Hailing from the same community that they serve makes it easier to build trust, and the women can take on as much work as they like.

Livestock owners pay a fixed sum for each service – about 12 cents for every vaccination, for example – and goat nurses also receive a small stipend from the government. Ahilya Devi says she makes anywhere from $25 to $85 a month. That money goes toward her children’s school fees, groceries, and other household expenses – and, occasionally, a personal treat like makeup.

“Earlier, I had to consult my husband for every expense,” she says, “but now if I want to buy something, I don’t hesitate.”

Empowering women through goats

To be sure, the work comes with challenges. Farmers are often reluctant to pay for services, says Dr. Singh, and there’s the risk that goat nurses may be threatened or harmed if an animal dies under their care. In an essay about the Pashu Sakhi program, Observer Research Foundation senior fellow Arundhatie Biswas Kundal emphasized the need to “provide the women with adequate protection and aid them in registering complaints.”

Still, the initiative has paid rich dividends. In some districts of Bihar, Maharashtra, and Haryana, goat mortality fell to single digits. Between 2012 and 2019, Jharkhand’s goat population – which had become stagnant – grew by nearly 40%, and another livestock census is expected to take place this year. Spurred by the program’s success, goat nurses in some parts of Jharkhand are also being trained to cater to larger animals like cattle, says Dr. Singh.

Armed with knowledge about animal rearing, some goat nurses, like Ritmani Devi, have channeled their training into increasing the size of their own herd. She now has 14 goats.

There’s also a less tangible outcome. The initiative has contributed to “the building of social capital and self esteem” among urban women, wrote Dr. Kundal. People often refer to the goat nurses as “doctor didi,” meaning an elder sister or person you think highly of. And empowering women has the potential to improve other developmental indices, argues Dr. Singh. “When a woman earns something extra, she always invests it in her children’s nutrition and their education,” he says.

But none of this happens overnight. When Ahilya Devi first started as a goat nurse, people would look at her with some suspicion.

“Even those from my own village did not recognize me, because I did not step out of the house much,” she says.

Now, nearly a decade later, they welcome her into their homes with respect.

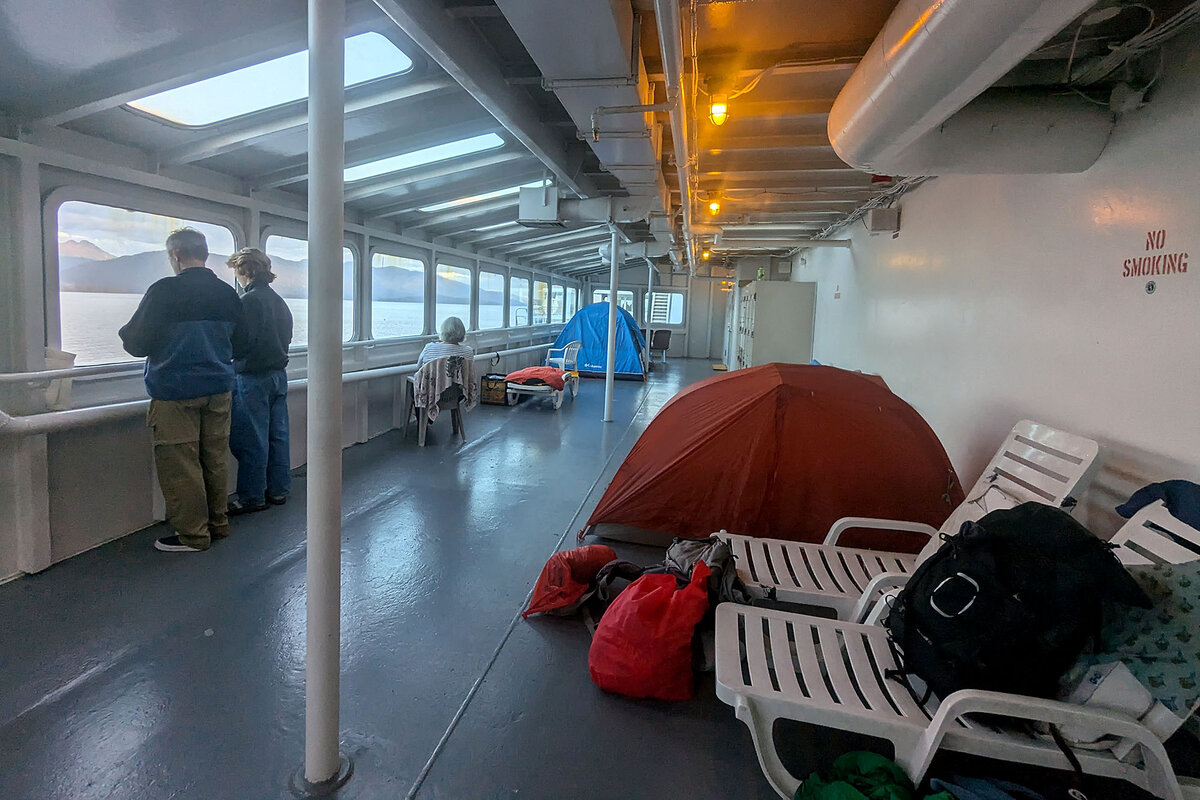

The ‘other’ Alaska cruise: Got a week? Pitch your tent on deck.

In the shadow of luxury cruise liners, the humble Alaska Marine Highway System wends through the Inside Passage connecting remote communities while helping tourists disconnect.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Laura Randall Contributor

Alaska luxury cruise ships disgorge over a million visitors a year in the downtown Juneau port. While, at a humbler port of call in Auke Bay nearby, a smaller, homier, slower, and cheaper people’s cruise putters in and out.

The Alaska Marine Highway System quietly transports locals, their cars, groceries, pets, and fishing gear, as well as tourists along the 3,500-mile crescent of archipelagoes along the southern Alaska coast. Its traverse offers front-row views of the vast, rugged landscape that defines the 49th state.

The catch? Bring your own ... everything.

“It’s entirely DIY,” says Jennie Flaming, host of the podcast “Alaska Uncovered.”

Dining is limited to vending machines and a self-serve cafeteria. Towels and bedding are extra. There’s no Wi-Fi, so passengers entertain themselves with games, puzzles, and books. Some bring sleeping bags or set up tents and hammocks in the solarium and upper decks. And, settling into the slow pace triggers a rare sense of freedom in the total disconnect from technology.

“The ferries are our trains,” notes David Kiffer, mayor of Ketchikan. “They are the blue highways that connect us, and without them we could not exist as a cohesive region.”

The ‘other’ Alaska cruise: Got a week? Pitch your tent on deck.

Framed by snowcapped mountains and forest-blanketed islands, the MV Kennicott glides into Auke Bay on the outskirts of Juneau with little fanfare. It’s two hours late, but the passengers lining up to board aren’t overly concerned. No one who buys a ferry ticket on the Alaska Marine Highway System is in a hurry.

The Kennicott – a 382-foot-long vessel with sleeping cabins, observation lounges, and a heated solarium deck – belongs to a fleet of publicly owned ships plying the 3,500-mile crescent of archipelagoes along the southern Alaska coast. They connect people and vehicles to 30 remote, ferry-dependent Alaskan towns; some operate year-round.

The Kennicott is a fraction of the size of the ships of the booming Alaska cruise industry that dock in downtown Juneau. And it’s far less expensive. But it traverses similar terrain and offers front-row views of the vast, rugged landscape that defines the 49th state.

The catch? Bring your own ... everything.

“It’s entirely DIY,” says Jennie Flaming, host of the podcast “Alaska Uncovered.” Dining is limited to vending machines and a self-serve cafeteria. Towels and bedding are extra. There’s no Wi-Fi, so passengers entertain themselves with games, puzzles, and books. Some bring sleeping bags or set up tents and hammocks in the solarium and upper decks. (Pro tip: Pack duct tape in case the winds pick up.)

A critical connector

Still, the ferries remain as meaningful to many Alaskans as the state glaciers after which each is named. Established in the 1960s by a state bond measure, the Alaska Marine Highway System is the only marine route recognized as a National Scenic Byway and All-American Road. Its stops include Gustavus, near Glacier Bay National Park, and (summer only) Dutch Harbor, a crab fishing hub in the Aleutian Islands.

“The ferries are our trains,” notes David Kiffer, mayor of Ketchikan, a port and cruise ship destination along the Kennicott’s route. “They are the blue highways that connect us, and without them we could not exist as a cohesive region.”

High school teams once used them to travel to sports tournaments and debate competitions. Residents of remote coastal areas hopped on to visit family and access services in other towns, or to travel to Canada and the Lower 48. They can bring their cars and pets.

Ferry ridership has declined sharply, from 400,000 in 1994 to 180,000 last year. In contrast, Juneau alone drew 1.7 million luxury cruise ship passengers in 2023.

Ferry schedules are “complicated and weird,” notes Ms. Flaming. “It doesn’t really work to hop on and hop off unless you have several weeks for your trip.”

Some of the vessels are pushing 50 years old, and require expensive repairs and lengthy periods off the water. Earlier this month, the Federal Transit Administration awarded the ferry system $177 million for improvements. Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski, who recalls riding the ferry out of Ketchikan as a kid, backed the award, which will help replace one of the original vessels with a hybrid-powered ferry.

Pitching tents and staking out board games

Outside the Auke Bay Ferry Terminal, on a 65-degree summer day, my husband, son, and I line up behind a man in a baseball cap balancing Costco-sized boxes of chips and popcorn atop a hard-shell suitcase. He’s headed 200 miles south to Ketchikan, where he’ll catch an interisland ferry to Prince of Wales Island with his wife and preteen daughter to camp and catch enough halibut to last the winter.

Nearby, a scarlet-haired teacher from Pennsylvania is capping off visits to Denali and Glacier Bay National parks by taking the Kennicott to Bellingham, Washington. It’s a 77-hour, 830-mile journey that might make a less adventurous traveler impatient, but she’s bubbling with a first-timer’s enthusiasm, ready to pitch her tent.

My family is bound for Petersburg, a commercial fishing hub on Mitkof Island, where our older son spent the summer working on a trails crew. The ferry trip is eight hours, versus 30 minutes by commercial plane. We’re prepared for – and even giddy about – the slow pace.

We settle into a booth with books, magazines, and that rare sense of freedom triggered by a total disconnect from technology. The high-backed chairs have seen better days, but are nap-friendly. Other passengers beeline toward tables and help themselves to puzzles and games provided by the ship.

As the vessel leaves the harbor, we venture onto the blustery deck and watch Auke Bay and the Mendenhall Glacier recede from view.

The similarities with a cross-country Amtrak trip become clear: the first-come, first-served observation lounges; the coexistence of characters from all walks of life; the “lucky me” feeling as we witness stunning scenery impossible to see by car.

We learned about the Alaska ferry, as many non-Alaskans do, through friends. They’d sailed the MV Columbia between Juneau and Bellingham more than a decade ago and gushed about the experience as weird, wonderful, and truly Alaskan. They recalled daily ranger talks on whales and salmon, a dining room with fresh Alaska seafood, linens in every stateroom.

Mayor Kiffer, for his part, still rides the ferries with the hope that the system will someday return to its glory days. His preferred itinerary includes a stateroom, a good book, and plenty of time to watch the scenery roll by.

“Sometimes I just take the ferry from Ketchikan to Skagway and back, and I never even get off,” he says. “It takes three days and I am truly in my happy place.”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Avoiding war by truth-telling

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

For nearly two years, the Philippines has been on a truth-telling campaign. The Southeast Asian nation has invited journalists to witness aggressive actions by Chinese ships near rocks and reefs that are clearly within the Philippines’ legal domain. In August, for example, a “60 Minutes” crew was on a Philippine coast guard ship when it was rammed by a Chinese ship. Has this public exposure of China’s territorial grab done anything to head off a dangerous showdown?

This month, the Philippines plans to find out. It will ask the United Nations General Assembly to look over evidence of violent incidents by China in hopes that truth will prevail in persuading Beijing to honor international maritime law.

For now, China’s taking of islets still goes on. Yet the more that this truth-versus-lies contest continues, the more the Philippines has been winning on a bigger stage. It has gained wide diplomatic and military support from nations as far away as South Korea.

China refers to the truth-telling campaign by the Philippines as “cognitive warfare.” But truth’s power lies in dissolving lies. At the U.N. and elsewhere, the Philippines aims only “to talk some sense” into China, as one of its diplomats put it.

Avoiding war by truth-telling

For nearly two years, the Philippines has been on a global truth-telling campaign, dubbed the “transparency initiative.” The Southeast Asian nation has invited journalists aboard its security vessels to witness aggressive actions by Chinese ships near rocks and reefs that are clearly within the Philippines’ legal domain. In August, for example, a “60 Minutes” crew was on a Philippine coast guard ship when it was rammed by a Chinese ship near Sabina Shoal.

Has this public exposure of China’s territorial grab far from its shores done anything to head off a dangerous showdown?

This month, the Philippines plans to find out. It will ask the United Nations General Assembly to look over evidence of violent incidents by China in hopes that truth will prevail in persuading Beijing to honor international maritime law.

For now, China’s taking of islets in the South China Sea still goes on. And Beijing has launched a public relations campaign of its own. According to “60 Minutes,” for example, the Chinese government publicized its version of the ramming incident soon after it happened, blaming the Filipinos.

Yet the more that this truth-versus-lies contest continues, the more the Philippines has been winning on a bigger stage. It has gained wide diplomatic and military support from nations as far away as South Korea and Germany.

“We have the law on our side, but the battleground is for other countries to help us recognize our rights,” said the country’s defense secretary, Gilberto Teodoro Jr.

At home, Filipinos now widely support their country standing up to Beijing after seeing videos of China’s aggression. Abroad, the Philippines now has closer military ties with Australia, Japan, Singapore, and India. It has also welcomed the United States to use four military bases, install a defensive missile system, and back up a 1951 mutual defense treaty between the two countries.

The transparency strategy by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is modeled on Ukraine’s experience of rallying countries to its side by exposing Russian atrocities against Ukrainian civilians. “The more the world sees of China’s claims and the ugly way it tries to enforce them,” stated The Economist magazine, “the less legitimate they will seem.”

China refers to the truth-telling campaign by the Philippines as “cognitive warfare.” But truth’s power lies in dissolving lies. At the U.N. and elsewhere, the Philippines aims only “to talk some sense” into China, as one of its diplomats put it. If anything, truth can bring peace.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Defending our cities

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Thomas Fuller

As we understand that God could never create evil, we’re able to witness a decrease in crime.

Defending our cities

We hear daily about our cities’ woes. Stories of injustice, violence, and criminal activity seem at flood tide worldwide.

At one point, some houses in my own neighborhood had been broken into and robbed. Several of us met one night and decided to form a neighborhood watch.

I also decided to pray. I thought about the Bible record of Nehemiah, who saw his city, Jerusalem, facing a dire, potentially deadly, crisis (see Nehemiah, chapters 2-6). He addressed the rulers and citizens of the city, voicing the need to rebuild the surrounding wall to protect the city from its foes.

But more importantly, his faithful prayers led him to recognize that the only sure protection is God. Although neighboring rulers employed threats, subterfuge, and unfounded rumors to try to halt their progress, Nehemiah courageously stayed the course.

As the work began, he said to his enemies, “The God of heaven, he will prosper us; therefore we his servants will arise and build: but ye have no portion, nor right, nor memorial, in Jerusalem” (Nehemiah 2:20). To me this meant that God has all power, and that evil had no current presence in Jerusalem, no right to a future presence, and no evidence of a past presence.

As part of our neighborhood watch, some of us agreed to walk the streets after dark. In preparing for these walks, I pondered God’s, divine Mind’s, universal government, illumination, and protection of all its ideas. Doing so enabled me to silence intruding fears, denying them any legitimacy – now, in the future, or even in the past.

Christ Jesus said of his followers, “My Father, which gave them me, is greater than all; and no man is able to pluck them out of my Father’s hand” (John 10:29). No one can be pulled away from God. And since the Bible says man is created in the image of God (see Genesis 1:27), we include no criminal element, no envy, and no lust for the goods of others. All of God’s children, who are entirely spiritual, are fully satisfied with the limitless riches He provides.

Moreover, I reasoned that “error of any kind cannot hide from the law of God,” as we read in “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures” by the discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy (p. 95).

All of these truths are laws of safety and justice to our communities, including to any would-be wrongdoers. God’s laws bless one and all.

Science and Health also encourages, “... those who discern Christian Science will hold crime in check. They will aid in the ejection of error. They will maintain law and order, and cheerfully await the certainty of ultimate perfection” (p. 97).

We are all capable of discerning Christian Science, the Science of Christ, the law of divine Truth that moves us forward in productive ways.

About this time, my company moved me to another city 700 miles away. My family would join me when the school year was over. One evening after work, I turned on the television and foolishly watched a dreadful movie that was full of criminality.

I realized I couldn’t go to bed with my thought full of those cruel images. So, I prayed earnestly for the next two hours, until I felt mentally cleansed of the grime of crime.

Evil cannot even exist, let alone flourish, in the omnipresence and omnipotence of good. I felt at peace knowing that God reigned and that evil had no portion, no right, and no memorial – in my thought or anywhere.

That same night, my wife was awakened by a phone call from someone claiming to be a college friend of mine. My wife explained that I was out of town, but she felt something had been wrong about the call.

She dialed 911, but just after she gave our address, the phone went dead. (This was before cellphones.) The criminal was in our backyard. He had attached a handset to our phone line and made the call from behind our house before cutting the line.

The alert 911 dispatcher quickly sent a nearby police car to our house. The blinking lights caused the thief to run off. However, he had not yet put on his gloves, and he had left behind his wire cutters.

The police were able to get his fingerprints and very soon arrested him. The break-ins stopped, and many of our neighbors’ stolen goods were recovered from his storage area.

From this experience, I learned the necessity of watching my thought, not taking in images of crime or cruelty, and resisting the lie that God’s likeness can become a victim or victimizer.

Our cities need alert watchers. Our prayers enable us to do this, and to recognize our right, duty, and authority to spiritually defend our cities, positively and joyously.

Adapted from an article published on sentinel.christianscience.com, April 28, 2022.

Viewfinder

Preparing for Helene

A look ahead

Thank you for coming along with us today. Thursday’s Christian Science Monitor Daily will take you to Congress, where lawmakers are stepping up their efforts to figure out what’s next for the Secret Service after two assassination attempts against Donald Trump.

And, yes, the link in yesterday’s intro was wonky. If you’d like to read my column about facts, you can do so here. (We promise this one works.)