- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Helene’s powerful floods prompt urgent relief efforts – and a wake-up call

- Today’s news briefs

- Israel mulls Lebanon invasion. Hezbollah ‘coup de grâce’ or quagmire?

- Inside battered Hezbollah, words of defiance: ‘All red lines are gone’

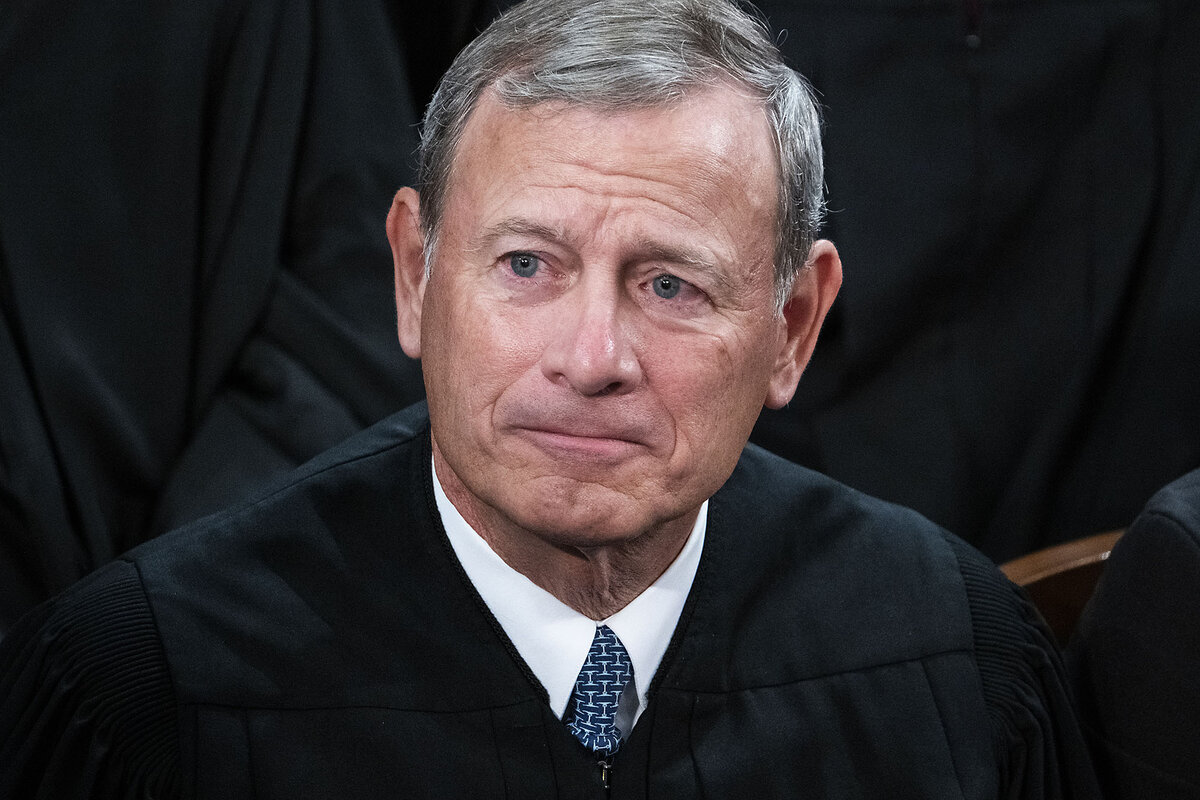

- Entering a new Supreme Court term, John Roberts is as enigmatic as ever

- How India’s crackdown transformed Kashmir’s politics

- In ‘The Wild Robot,’ a 5-star fable for our AI age

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

News at humanity’s doorstep

Preparing the Daily means making decisions about story order that imply a kind of hierarchy. Some days that’s hard.

Today, editors talked about Lebanon, where airstrikes have leveled residential towers, threatening to widen a conflict. About fast-rising waters in the mountains of the U.S. South. About stories we can’t yet get to, such as flooding in Nepal.

It’s impossible to apportion empathy, or to rank where understanding is needed most. We do our best, over time. We strategize to get into position to report with care. There is no hierarchy of heart when all of humanity is close to home.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

Helene’s powerful floods prompt urgent relief efforts – and a wake-up call

The immediate focus in the wake of Hurricane Helene is on recovery and relief. Another lesson is also emerging: More preparation is needed in places once considered low-risk from extreme weather.

-

By Stephanie Castellano Special contributor

-

Stephanie Hanes Staff writer

Communities across the U.S. southeast are reeling from devastation left by what scientists say is, in effect, a new type of storm – one whose destructive force is felt far more broadly, and much farther inland, than that of typical hurricanes of the past.

Hurricane Helene crashed into Florida’s Big Bend coast as a Category 4 storm Thursday night, leaving scenes of battered houses and flooded communities by the coast. But its damage is most severe in places where people were neither expecting nor well prepared for a tropical deluge – in particular, mountainous North Carolina.

Officials’ immediate focus is on recovery and relief. But a lesson for the future is also sinking in: The storm we didn’t know to be ready for is, increasingly, the kind of storm we need to be ready for.

Hurricane Helene is the third major storm to barrel through Florida’s northern Gulf Coast in just over a year. Here, residents are taking stock.

The storm damage clearly shows what needs to be done to improve resilience, says Heath Davis, resident and former mayor of Cedar Key, a tiny barrier island. “You have to think about it that way, otherwise it gets too sad.”

Helene’s powerful floods prompt urgent relief efforts – and a wake-up call

Communities across the U.S. southeast are reeling from devastation left by what scientists say is, in effect, a new type of storm – one whose destructive force is felt far more broadly, and much farther inland, than that of typical hurricanes of the past.

Hurricane Helene crashed into Florida’s Big Bend coast as a Category 4 storm Thursday night, leaving scenes of battered houses and flooded communities by the coast. But its damage is most severe in places where people were neither expecting nor well prepared for a tropical deluge – in particular, mountainous North Carolina, where flood waters swept away entire neighborhoods, downed power and water systems, and crushed roads that connected residents.

More than 100 people have lost their lives in the storm, according to officials, and hundreds are missing. About 2 million remain without power, and tens of thousands are still without potable water. Officials’ immediate focus is on recovery and relief. But a lesson for the future is also sinking in: The storm we didn’t know to be ready for is, increasingly, the kind of storm we need to be ready for.

Indeed, Helene’s rapid intensification and stunning destruction in places once considered “climate havens” revealed what scientists have long warned are stark vulnerabilities in American infrastructure and policy at a time when global warming is exacerbating extreme weather. The storm’s aftermath has also highlighted the sort of resilience experts say will be needed to rebuild and prepare for a warmer future.

Still an alarming situation

In Cedar Key, Florida, where Helene crashed into the coast and sent a storm surge of more than 9 feet above the normal high tide line, people shared water bottles and snacks, and helped each other move debris into piles. In Augusta, Georgia, a region that counted at least 21 deaths caused by the storm, neighbors joined together to try to move fallen trees by hand. In the hill communities around Asheville, North Carolina, cut off from surrounding areas by landslides and roadways crushed by rushing water, friends shared power, gas-fueled grills, and the rare cellphone connectivity.

“Neighbors are coming out into the street to talk to one another,” says Greg Lambert, an architect who lives in the Oteen area of Asheville, just south of Interstate 40, portions of which collapsed in the storm. “It’s unifying, in a way.”

But the situation is also still alarming, he says. The main roads in and out of his city are closed to all but emergency traffic, and many hamlets are cut off from the main population center – islands within an island, as one commentator put it Sunday. Reaching these areas is – and will continue to be – a huge challenge, officials say; relief efforts are employing everything from helicopters to mules in order to reach stranded residents.

Although Mr. Lambert says he saw power crews working to repair poles and clear the many downed trees, the regional energy company, Duke Energy, said in a statement Sunday that it could be days before all customers have power restored. And throughout the city, few people have potable water.

“Extensive repairs are required to treatment facilities, underground and aboveground water pipes, and to roads that have washed away which are preventing water personnel from accessing parts of the system,” the city announced in a statement Saturday. “Although providing a precise timeline is impossible, it is important to note that restoring service to the full system could potentially take weeks.”

Federal Emergency Management Agency Administrator Deanne Criswell said Sunday that the Army Corps of Engineers is helping to restore water service, and that FEMA has search and rescue teams working in western North Carolina and is working to bring in satellite communications for residents without cell service.

“I don’t know that anybody could be fully prepared for the amount of flooding and landslides that they are experiencing right now,” she said on the television show “Face the Nation.”

Preparing for risks in new places

The multistate nature of the storm also makes recovery efforts extra challenging, she says. Nearly a million people lost power in South Carolina, where at least 25 people died in the storm, according to officials. Atlanta received what state climatologist Bill Murphy said was an “unprecedented” 11.12 inches of rainfall in a 48-hour period.

But in some ways, preparing for the unprecedented is exactly what climate researchers have been encouraging communities to do for years. Astrid Caldas, a senior climate scientist for community resilience at the Union of Concerned Scientists, warned in a press release last week that Helene was supercharged by high ocean temperatures made hundreds of times more likely because of climate change. And repeatedly, she and others have said that the impacts of storms can extend to areas beyond those typically thought of as “at risk” for hurricanes.

“Asheville is over 2,000 feet above sea level, and ~300 miles away from the nearest coastline. No place is safe from climate change,” wrote Lucky Tran, director of Science Communication and Media Relations at Columbia University, on the social media platform X.

And many worry that governmental policies have not caught up with this “everywhere” risk.

Most homeowners’ insurance policies, for instance, do not cover flooding damage. And while the federal government requires homeowners who live in FEMA-designated high flood risk areas to purchase flood insurance, much of the inland flooding that has occurred in recent years is outside those maps. That’s certainly true in western North Carolina.

“I don’t think that most people who move to the mountains expect to buy flood insurance,” says Mr. Lambert.

Rebuilding in Cedar Key, Florida

Even in areas where residents know flooding is a risk, insurance can be problematic. Increasing numbers of people here are deciding that premiums are just too high, says Heath Davis, resident and former mayor of Cedar Key, a tiny barrier island on Florida’s northern Gulf Coast. Many Cedar Key homeowners have chosen to “roll the dice” and go without insurance, he says. Of the insured homeowners on the island, he guesses that very few have a separate flood insurance policy.

“I don’t know anyone who is properly insured,” he says.

Hurricane Helene is the third major storm to barrel through Florida’s northern Gulf Coast in just over a year. And due to Cedar Key’s precarious position in the Gulf, many homes and businesses on the island don’t currently qualify for home or flood insurance. If insurance is obtainable, monthly premiums for flood insurance alone can cost as much or more than a typical monthly mortgage payment, Mr. Davis says.

Hurricane Helene sent several feet of water coursing through Mr. Davis’ own home. It hadn’t been eligible for insurance, he says, because it was older and not built to modern hurricane code. Making the improvements necessary to change that would have cost more than the home was worth, he says.

Now he and his wife will have to tear it down and rebuild from scratch.

Other Cedar Key homeowners find themselves in the same position. Even those whose homes are eligible for flood insurance often choose to go without it, due to “astronomical” premiums, says City Commissioner Jeff Webb. A common sentiment among islanders, he says, is that “Premiums are so expensive you might as well save the money and use it on repairs.”

On Sunday, three days after the storm, the island is quiet. There are some homes and shops with their innards still strewn about them; others squat behind organized piles of debris. Jordan and Shannon Keeton work around their home on one of the island’s highest points, where it escaped the flood damage that ravaged homes even just down the street. Their restaurant wasn’t so fortunate.

The shell of 83 West, one of Cedar Key’s biggest restaurants, sits on Dock Street, a short drag lined with other seafood eateries and touristy gift shops. The fact that it’s built over the water renders it uninsurable for flood or wind damage.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Federal Emergency Management Agency

After Hurricane Hermine in 2016, the Keetons had to close for about eight weeks. After Idalia in 2023, they closed for 13 weeks. After Debby this summer, they closed for 3 weeks. Now, they’re closed for the foreseeable future.

“It’s a lot of unknowns,” says Ms. Keeton. After Hurricane Idalia, the Keetons applied for a loan through the U.S. Small Business Administration to help with recovery costs, one of the only options available to them. Without an insurance policy on their business, they used their mortgage to back the loan. Now, they’re worried that paying it back will mean losing their house.

When water and sewer services will return to the island is another open-ended question.

“They always tell us to ‘Build back better,’” says Mr. Keeton. “It’s like, How can I do that? I’m over my head right now in debt.”

The struggle to insure their homes and businesses is not new for Cedar Keyans. However, Mr. Davis says that the island is a “magnet for resilient people from all walks of life.”

And the storm damage clearly shows what needs to be done to improve the island’s resilience. It “shows new residents the path forward,” says Mr. Davis. “You have to think about it that way, otherwise it gets too sad.”

Stephanie Castellano reported from Cedar Key, Florida, and Stephanie Hanes from Ossipee, New Hampshire.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Federal Emergency Management Agency

Today’s news briefs

• Dockworkers set to strike: U.S. ports from Maine to Texas could shut down if a union representing 45,000 dockworkers goes through with a threatened strike. The 36 ports affected handle roughly half of the nation’s cargo from ships.

• Shift in asylum rules: The number of daily unauthorized migrant crossings between official ports of entry at the U.S. southern border will have to average below 1,500 for nearly a month before the restrictions on access can be lifted. That marks a sharp decline in the daily allowance and an increase in the duration of the decline.

• Britain shutters last coal-fired plant: The Ratcliffe-on-Soar station in central England is due to end its final shift at midnight Sept. 30, marking the end of 142 years of coal-generated electricity in the nation that sparked the industrial revolution.

• VP candidates to debate: Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz and Sen. JD Vance of Ohio will meet Oct. 1 for their first and only scheduled vice presidential debate. The 90-minute debate will be hosted by CBS News.

• Far-right gains in Austria: Voters hand a first-ever national election victory to the Freedom Party Sept. 29, illustrating rising support for hard-right parties in Europe fueled by concern over immigration levels and the economy.

Israel mulls Lebanon invasion. Hezbollah ‘coup de grâce’ or quagmire?

Israeli attacks have killed Hassan Nasrallah, the head of the Iran-backed militia Hezbollah, and sown disarray in the group’s ranks. But have they done enough to make a ground assault into Lebanon feasible?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Almost a year after the Israeli army was caught by surprise and humiliated by Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, its forces are back on the offensive.

Assassinating archenemy Hassan Nasrallah, leader of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah paramilitary group; launching a blitz that wiped out many of its top commanders; and leaving the organization dazed and immobilized – for the time being – Israel has reclaimed its role as a military powerhouse.

The question it faces now is how far to press its advantage at this potentially game-changing moment.

After 10 days of heavy aerial bombardment of Hezbollah positions, the army appears poised to launch a ground invasion of southern Lebanon in order to dislodge heavily dug-in forces near the border.

That, the government hopes, would make it safe for Israelis who live close to the border to return home; 65,000 of them were evacuated last October when Hezbollah began firing rockets into Israel in support of Hamas.

Israeli forces might, however, expand their ambitions and make a bid to destroy Hezbollah as a fighting force. That would deal a grave blow to Iran, Hezbollah’s patron, and weaken the regional “Axis of Resistance” that includes Iran, Syria, Hamas, and Hezbollah. That could spark a retaliatory strike by Tehran, which could quickly explode into regional war.

Israel mulls Lebanon invasion. Hezbollah ‘coup de grâce’ or quagmire?

Almost a year after the Israeli army was caught by surprise and humiliated by Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, its forces are back on the offensive.

Assassinating archenemy Hassan Nasrallah, leader of the Iranian-backed Hezbollah paramilitary group; launching a blitz that wiped out many of its top commanders; and leaving the organization dazed and immobilized – for the time being – Israel has reclaimed its role as a military powerhouse.

The question it faces now is how far to press its advantage at this potentially game-changing moment.

At stake is not only the future of the 65,000 Israelis forced from their homes near the northern border with Lebanon by Hezbollah rocket fire. Israel has the opportunity now, the government believes, to hobble the most powerful member of the Iran-backed “Axis of Resistance.”

“For decades, he [Mr. Nasrallah] terrorized us in the most immediate sense,” Shimrit Meir, a former adviser to Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, told the Israeli podcast “Unholy.” Israel should capitalize on his death to “shape a reality that is different from this ring of fire that Israelis were in up until two weeks ago,” surrounded by hostile forces such as Axis members Hamas, Syria, and the Houthis in Yemen, she argued.

Meanwhile, pressure is mounting in Israel for a ground incursion into Lebanon, especially from those living along Israel’s northern border. They have seen over 8,000 Hezbollah rockets shot at their towns and villages in the past year, while they have been placed in temporary housing elsewhere.

Even in their weakened state, Hezbollah forces have continued to fire rockets in recent days, and deeper into the country than before.

The Israeli government has reportedly told Washington that a ground invasion is imminent. Defense Minister Yoav Galant hinted at an invasion Monday when he addressed Israeli soldiers on the border, and the army has declared some border communities in the north “closed military areas” – another indication of unusual military activity.

The Pentagon said Monday that Washington would send a “few thousand” troops to the Middle East to bolster security and to defend Israel if necessary.

Ground assault in the offing?

Moshe Davidovitz, chairman of the forum of residents on the northern front line, says that they will feel safe enough to return to their homes only if Israeli ground forces move into southern Lebanon and push Hezbollah fighters back from the border. Otherwise, they fear, Hezbollah militants might break across the border in a Hamas-style assault.

“In order to protect our communities, we have no choice but to surgically clean out what Hezbollah built over years so close to the border,” Mr. Davidovitz argues.

That is thought to include an intricate network of tunnels deep underground near Israel’s border, used to hide troops and long-range missile launchers, says Miri Eisen, director of the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism in Herzliya.

Israel has created and occupied a military “security zone” in southern Lebanon before, for 15 years until 2000 when it withdrew its forces under pressure from public opinion, weary from sustaining casualties.

This time, says Eitan Shamir, director of Bar-Ilan University’s Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, the Israeli army has two options: It could take and hold territory south of the Litani River, which runs parallel to the border about 20 miles north of it, or it could try to drive deeper into Lebanon to further degrade Hezbollah infrastructure, although “for obvious reasons the IDF [Israel Defense Forces] would be reluctant to stay there.”

War or peace?

As challenging as it would be to clear out Hezbollah’s tunnel network, says Professor Shamir, especially in the mountainous terrain of southern Lebanon, much of it has already been degraded. The Israeli army spokesperson said on the social platform X that Israel had “dismantled” Hezbollah’s “Missiles and Rockets Force” in repeated bombing raids.

“Hezbollah is not in the same shape in southern Lebanon, and there’s also no leadership to direct and command them,” says Professor Shamir. Fighters might, however, revert to the guerrilla tactics of Hezbollah’s early days, he suggests.

Furthermore, he says, Israeli soldiers would have experience from fighting Hamas in Gaza, including in its extensive tunnel network.

Mr. Galant, Israel’s defense minister, appeared to be giving commanders and troops a pre-ground war pep talk in remarks to them Monday. “The elimination of Nasrallah is an important step, but it is not the final one,” he said. “In order to ensure the return of Israel’s northern communities, we will employ all of our capabilities, and this includes you. Good luck.”

In the hours before Mr. Nasrallah’s assassination, French and U.S. officials were finalizing a proposal for a three-week truce between Israel and Hezbollah; they are still promoting the plan, warning that the region stands on the brink of a catastrophic all-out regional war involving Iran.

Israelis appear to be divided between those who want to do more damage to Hezbollah while Israel has the momentum, and those calling for a deal that would both stop the war in Gaza, freeing the remaining hostages, and end hostilities with Hezbollah.

Ms. Meir, the former government adviser, expects the harder line to prevail. “When your enemy is on the ground bleeding, you don’t lend him a hand. You exhaust the opportunity you have; you win,” she argued. “And I think that is what we will strive for, and I think a deal will be easier to reach that way.”

Inside battered Hezbollah, words of defiance: ‘All red lines are gone’

The Lebanese militia Hezbollah has lost its charismatic leader, who delivered battlefield gains for decades, and absorbed a series of heavy blows from Israel. How ready are its fighters to resist Israel on the ground?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia and its fighters remain defiant, even expressing confidence, despite escalating Israeli attacks on its top commanders and missile arsenal that culminated Friday with the assassination of the group’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah.

With little significant retaliation yet from the Iran-backed Hezbollah – and uncharacteristically limited rhetoric from Iran vowing revenge – Israel expanded its airstrikes over the weekend to other anti-Israel militant groups in Lebanon and as far away as Yemen.

That has raised questions about whether Israel has diminished Iran’s most potent regional ally in just two weeks. It has killed 20 members of its leadership pyramid, wounded 3,000 militia members, and cut key lines of communication by exploding pagers and walkie-talkies. Hundreds of Israeli airstrikes have left more than 1,000 Lebanese dead, both fighters and civilians.

Yet Hezbollah officers say in interviews that they have restored most of their communications network and that the most powerful and precise elements of their missile arsenal remain intact. Hezbollah will soon be ready to fight back “full throttle.”

“We are going to show the world what we are capable of doing,” says a Hezbollah missile specialist, who gives the pseudonym Hassan.

“All red lines are gone” after the assassination of Mr. Nasrallah, he says. “We are going to fight this war without any rules.”

Inside battered Hezbollah, words of defiance: ‘All red lines are gone’

Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia and its fighters remain defiant, even expressing confidence, despite escalating Israeli attacks on its top commanders and missile arsenal that culminated Friday with the assassination of the group’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah.

With little significant retaliation yet from the Iran-backed Hezbollah – and uncharacteristically limited rhetoric from Iran vowing revenge – Israel expanded its airstrikes over the weekend to other anti-Israel militant groups in Lebanon.

It also struck other members of Iran’s “Axis of Resistance” as far away as Yemen.

That has raised questions about whether Israel has diminished Iran’s most potent regional ally in just two weeks. It has killed 20 members of its leadership pyramid, wounded 3,000 militia members, and cut key lines of communication by exploding pagers and walkie-talkies. Hundreds of Israeli airstrikes have left more than 1,000 Lebanese dead, both fighters and civilians.

On Monday, a U.S. official was quoted as saying Israeli military chiefs had warned Washington that a limited Israeli ground incursion into southern Lebanon was “imminent” to clear Hezbollah infrastructure along the border.

Also Monday, the Israel Defense Forces said on the social media platform X that it had “dismantled” Hezbollah’s “Missiles and Rockets Force” with a week of airstrikes. On Saturday the IDF said it intensified operations against Hezbollah’s “force build-up” by targeting “key weapon manufacturing sites” and, days earlier, striking smuggling routes from Syria.

Hezbollah officers: We’ll be ready to fight

Yet Hezbollah officers say in interviews that they have restored 70% to 80% of their communications network after temporarily losing contact with field officers in charge of firing missiles.

They also say the most powerful precision-guided, longer-range elements of Hezbollah’s missile arsenal remain intact. And Hezbollah will soon be ready to fight back “full throttle” with bombardments and can now, in any event, repel any Israeli ground invasion, the officers say.

“Our war hasn’t started yet, but it’s [about] to start, and we are going to show the world what we are capable of doing,” says a Hezbollah missile specialist, who gives the pseudonym Hassan.

“All red lines are gone” after the assassination of Mr. Nasrallah, he says. “We are going to fight this war without any rules.”

The Monitor has interviewed both Hezbollah officers quoted in this story several times in the past.

“We have a long way to go; we have a long war to fight,” says Hassan, a Hezbollah veteran of 23 years, when asked why the militia is still using mostly older rockets instead of the most powerful and precise weapons believed to be in its estimated prewar arsenal of 150,000 rockets, missiles, and drones.

“We cannot show them everything the first day. We cannot drop it on them the first day. But you’ll see. ... We know exactly what we are doing,” he says.

Nasrallah’s long leadership

Analysts attribute Hezbollah’s losses of the last two weeks to Israeli intelligence’s deep penetration of the Shiite group, which was founded with the help of Iran during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Mr. Nasrallah assumed leadership more than three decades ago, after his predecessor was killed by Israel. He gained mythical status among his followers in Lebanon and abroad as a truth-telling survivor who delivered military achievements against Israel in 2000 and 2006. During the Syrian civil war, he led Hezbollah’s rescue of a fellow Iranian ally, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

Mr. Nasrallah was killed in a barrage of 80 American-supplied bunker buster bombs and other munitions, which destroyed six residential buildings in Hezbollah’s southern Beirut stronghold of Dahiya. Confirmation of his death prompted scenes of uncontrolled grief and wailing by Hezbollah supporters on the streets, and an exodus of Shiites to safer areas of the capital.

Not all have been welcome. Some Shiite mourners waving Hezbollah flags were reportedly set upon and beaten by members of other Lebanese sects, which blame the Shiite militia and Iran for bringing another devastating war with Israel.

Heiko Wimmen, the International Crisis Group’s Beirut-based project director for Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon, says the Israeli attacks likely are having an impact on Hezbollah’s ability to fight back.

Hezbollah officers appear to have little operational security right now, and must assume they are being tracked. That could mean, he says, that if Hezbollah’s arsenals still exist and are functioning, “The expectation would be that the moment you start to activate them, they would be immediately destroyed.”

Hezbollah’s logic has changed

Until the killing of Mr. Nasrallah, there were still public arguments about the wisdom of showing “strategic patience,” and about not being baited by Israel into a wider war, to explain Hezbollah’s lack of a more forceful response to previous Israeli strikes, Mr. Wimmen says.

Indeed, Hezbollah’s reactions were carefully calibrated in solidarity with Hamas, after its attack on Israel last Oct. 7. Both Hezbollah and Iran had signaled a desire only for managed escalation, and not for an all-out war.

But now, “All the logic of holding back – it doesn’t add up anymore,” says Mr. Wimmen.

“From the perspective of Hezbollah, there is no meaningful difference between what is happening and what is to come, potentially, and all-out war,” he says.

On Monday, Hezbollah’s deputy leader, Naim Qassem, delivered a recorded message of defiance and sought to reassure reeling Hezbollah forces that revenge was coming and “victory” was certain. The white-bearded cleric did not name a new leader.

Israel had made no dent “at all” in Hezbollah’s military capacity, Mr. Qassem said, and militia weapons had been fired at targets up to 150 kilometers (93 miles) deep in Israel and sent 1 million Israelis into shelters, all while “exerting the minimum effort” as part of a broader war plan.

“What is being said by their [Israeli] media – that they have targeted and hit our military capabilities – this is a dream,” he said. “They will never be able to achieve that. ... The tools and equipment are there.”

Among those who will be ready for a more concerted fight is another Hezbollah officer, a stocky man who works on missile units and gives the pseudonym Jihad.

“Yes, Sayyid Nasrallah is dead. He’s a soldier like we are soldiers; he’s one of us, and he got killed like we get killed. ... He joined the team, that’s all,” says the 22-year Hezbollah veteran.

“Now we are going after [the Israelis]; we’re going to make them pay,” says Jihad. He uses an expletive in reference to Iran, which for a year has helped limit Hezbollah’s retaliation, to avoid a wider war that would directly pull in the United States and Iran.

“We are going to fight this war,” says the Hezbollah officer. “Don’t mention the Iranians to me anymore. We are in Lebanon here; we are going to fight the Israelis and teach them a lesson.”

A Lebanese researcher in Beirut contributed to this report.

Entering a new Supreme Court term, John Roberts is as enigmatic as ever

Chief Justice John Roberts has been reliably conservative since he joined the Supreme Court. But around him the court has become increasingly conservative – and aggressive – in recent years. Is it causing him to tack to the right?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Next week, John Roberts will gavel in his 20th term as chief justice of the United States. It has been an enigmatic two decades for the man in the center chair of the U.S. Supreme Court. But this October feels different, with the chief justice’s role coming under renewed scrutiny.

Chief Justice Roberts has long defied the liberal and conservative labels now routinely attached to members of the judiciary. Over years of growing partisanship and declining trust in U.S. institutions, he has cultivated a reputation as an institutionalist more concerned with the court’s public standing than with legal philosophy.

But after a term in which Chief Justice Roberts wrote landmark opinions benefiting former President Donald Trump, some court watchers are reevaluating that institutionalist image. Was last term an isolated incident? Or is the chief justice forging a new role for himself on a deeply conservative court?

“He [may have] consciously made a choice to move to the right,” says law professor Aaron Tang. Or “the big cases last term happened to involve an issue where he’s extremely conservative.”

“Only time will tell which of these two stories is the true story of the chief,” he adds.

Entering a new Supreme Court term, John Roberts is as enigmatic as ever

Next week, John Roberts will gavel in his 20th term as chief justice of the United States. It has been an enigmatic two decades for the man in the center chair of the U.S. Supreme Court. But this October feels different, with the chief justice’s role coming under renewed scrutiny.

A seasoned lawyer before he joined the high court, Chief Justice Roberts has long defied the liberal and conservative labels now routinely attached to members of the judiciary. Over years of growing partisanship and declining trust in U.S. institutions, including the court itself, he has cultivated a reputation as an institutionalist more concerned with the court’s public standing than with any legal philosophy.

But after a term in which he wrote landmark opinions benefiting former President Donald Trump, some court watchers are reevaluating that institutionalist image. Was last term an isolated incident? Or is the chief justice forging a new role for himself on a deeply conservative court?

“He [may have] consciously made a choice to move to the right,” says Aaron Tang, a professor at the University of California, Davis School of Law. Or “the big cases last term happened to involve an issue where he’s extremely conservative.”

“Only time will tell which of these two stories is the true story of the chief,” he adds.

A conservative chief on a conservative court

Chief Justice Roberts has been reliably conservative since he joined the Supreme Court. But around him the court has become increasingly conservative – and aggressive – in recent years.

Since former President Trump cemented a supermajority of six Republican-appointed justices in 2020, the high court has effectuated Republican policy goals including expanding gun rights, weakening the ability of workers to unionize, and overturning decades-old precedents involving affirmative action, abortion rights, and the regulatory power of federal agencies.

Thanks in part to Chief Justice Roberts, this sprint to the right had, until now, been more of a crawl. Some court watchers now wonder if the chief is leading the charge.

“This has been a conservative court, a Republican court ... but until recently it has not been a MAGA court,” said Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice, during a briefing on the court’s new term.

“The immunity case suggests we may be in new territory,” he added, referring to the court’s July ruling that former President Trump is at least presumptively immune from criminal liability for his official acts.

Over the decades, particularly in high-profile cases, the chief justice has prioritized the court’s institutional legitimacy over his ideological preferences. Sometimes he’s crafted narrow rulings that avoid seismic changes in the law. Sometimes he’s outright abandoned the court’s right wing.

One year, Chief Justice Roberts wrote the opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act, for example. A year later, he wrote the opinion gutting a key section of the Voting Rights Act. While he’s voted to expand gun rights and overturn Roe v. Wade, he’s also voted to uphold the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program and to apply federal antidiscrimination protections to transgender employees.

Four years ago, he supported the court’s decision to dismiss Mr. Trump’s appeals challenging the results of the 2020 election. Years earlier, he had publicly rebuked Mr. Trump for labeling a lower court judge an “Obama judge.”

Last term, however, the chief justice helped hand Mr. Trump a series of legal victories. In Trump v. Anderson, the court unanimously held that Colorado couldn’t remove the former president from its presidential primary ballot for engaging in insurrection. And in the most high-profile ruling of the term, Trump v. United States, Chief Justice Roberts wrote that former presidents are entitled to broad immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts.

But those opinions may not suggest that the already conservative justice is moving even further to the right. Given Chief Justice Roberts’ background as a lawyer in the Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations, the opinions aren’t that surprising, legal experts say.

“He’s been wanting to do that for his whole career,” says Carolyn Shapiro, a professor at the Chicago-Kent College of Law, referring to the recent expansion of presidential immunity.

“He has a very deep ideological commitment to” presidential power, she adds. “It’s about an effort to undo things that he thinks were done improperly in the post-Watergate era,” such as U.S. v. Nixon, when the court ruled that Richard Nixon had to turn over the Watergate tapes, effectively guaranteeing his resignation rather than face impeachment.

“I believed Roberts would be a natural leader”

A detailed report from The New York Times earlier this month seems to corroborate that. Quoting sources inside the court, including from the justices’ private memos, the Times detailed how Chief Justice Roberts pushed for a robust interpretation of presidential immunity from the moment the case reached the high court.

The chief justice also reportedly showed no interest in crafting a more moderate opinion that would attract votes from the court’s liberal wing. A similar dynamic played out in the Colorado case, where a unanimous decision on the outcome still prompted dissents from liberal justices critical of the ruling’s breadth.

But the court’s recent influx of right-leaning justices may have put the chief justice in a difficult position when it comes to consensus-building, some legal experts argue.

“His preference is for decisions that are less disruptive,” says Jonathan Adler, a professor at the Case Western Reserve University School of Law. But Chief Justice Roberts also doesn’t like fractured opinions.

If he can influence the opinion, adds Professor Adler, the chief justice “will usually choose to do something more aggressive than his preference if it produces a broader majority.”

His power as chief to assign opinions is valuable in this respect. Many of his more surprising opinions in the past likely wouldn’t have happened if another member of the court had been able to write them.

Indeed, it was Chief Justice Roberts’ qualities as a leader that persuaded George W. Bush to nominate him to the court.

“I believed Roberts would be a natural leader,” former President Bush wrote in his memoir. In fact, it was Brett Kavanaugh – a White House lawyer at the time and now a fellow justice – who advised the president to choose the man who “would be the most effective leader on the Court – the most capable of convincing his colleagues through persuasion and strategic thinking,” the former president recalled.

Justice Kavanaugh voted with Chief Justice Roberts in 95% of cases last term, according to Empirical SCOTUS. According to the Times report, he thanked the chief justice for what he described as “extraordinary work” on the presidential immunity opinion.

As Chief Justice Roberts enters his third decade on the court – a court that may be the most conservative in 90 years – how he uses his power and leadership skills will be telling.

How India’s crackdown transformed Kashmir’s politics

India’s disputed Kashmir region is witnessing a political transformation, as Delhi’s curb on separatist militancy and other forms of dissent pushes new candidates – and voters – to participate in local elections.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Much is at stake in Jammu and Kashmir’s legislative assembly elections.

The region is facing myriad problems stemming from the separatist insurgency that erupted here nearly four decades ago. Over the past five years, India’s central government has stripped Kashmir of its statehood, delayed local elections, and used sweeping new security laws to jail critics – all in the name of securing peace. Any group that fundamentally opposed Indian rule in Kashmir has been banned.

The elections, which run from Sept. 18 to Oct. 1, mark residents’ first shot to regain some local autonomy.

The mood on the ground is different from in years past. Gone are the calls to boycott elections and the looming terrorist threats that once deterred people from the polls. And although early data suggests overall voter turnout has remained static, many Kashmiris report feeling energized by a wave of new, independent candidates challenging the region’s traditional parties – sometimes from behind prison bars.

Street vendor Javaid Ahmed Bhat, who has never voted in local elections before, feels it’s imperative to do so this time. The days of anti-India street protests are over, he says, and now “we have to vote.”

How India’s crackdown transformed Kashmir’s politics

Street vendor Javaid Ahmed Bhat has never voted in local elections. Now, he feels it’s imperative.

Jammu and Kashmir – the contested, north Indian territory he calls home – is facing myriad problems, most stemming from the armed insurgency that erupted here in the late 1980s. Over the past five years, India’s central government has stripped Kashmir of its statehood, delayed local elections, expanded its military presence, and jailed critics of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), all in the name of securing peace in the region.

Kashmir’s highly anticipated legislative assembly elections run from Sept. 18 to Oct. 1, with results expected next week. They mark residents’ first shot to regain some semblance of local autonomy.

Although early data from the first two voting phases suggest turnout has remained relatively static compared to the last assembly elections in 2014, the mood on the ground is markedly different. Gone are the calls to boycott elections and the looming terrorist threats which once deterred people from the polls, and many Kashmiris are feeling energized by a wave of 346 independent candidates challenging the region’s traditional parties.

Rashid Wani, a businessman from south Kashmir, says the past five years have left many Kashmiris desperate to express their anger. “People are participating in elections [and] joining rallies,” he says. “These votes are against the BJP.”

Mr. Bhat agrees. The days of anti-India street protests are over, he says, and now “we have to vote.”

Delhi draws a redline

The Kashmir conflict is a territorial dispute rooted in India-Pakistan tensions, as well as the fact that the Muslim-majority region was never allowed to decide whether it wanted to remain with India, join Pakistan, or become independent. It has claimed more than 100,000 lives since 1988, when the armed struggle began.

In August 2019, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his BJP government downgraded the semi-autonomous state to a union territory, ruled directly by New Delhi, and then imposed a six-month communications blackout to contain the ensuing chaos. Indian officials have been broadly criticized for using sweeping new security laws to jail hundreds of activists, journalists, and politicians in the years since. Any group that fundamentally opposed Indian rule in Kashmir has also been banned.

“Today, we are trying to, in a sense, completely depoliticize the population,” says Ajai Sahni, founder and executive director of the New Delhi-based Institute for Conflict Management. “We are trying to undermine the traditional leadership over there.”

The BJP claims that peace and stability have now returned, but Mr. Sahni nuances that description, describing the armed movement as “very substantially contained.”

Data from his organization shows that dozens have been killed during at least 137 terrorism-related incidents this year, including gunfights and assassinations. Experts also note that the violence appears to be spreading from the Kashmir valley into the historically calmer region of Jammu.

Still, if Pakistan continues to weaken while Delhi maintains its military presence in Kashmir, Mr. Sahni doesn’t expect a resurgence in terrorism, and Delhi’s aggressive crackdown has certainly helped dismantle the network of separatist militants. But as long as separatist ideologies persist, the region remains vulnerable to political unrest.

That’s why, experts posit, Delhi has drawn a clear redline in local politics: No more separatism.

“You can’t question [India’s] sovereignty or try to incite people against the country,” says a senior Indian security officer, who wished to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to speak to the press. “Anyone who crosses this line will have to be dealt with through law enforcement.”

Candidates and parties that once were sympathetic to separatism are now focusing instead on issues like improving the economy, fostering peace with neighboring Pakistan, and addressing Delhi’s mass imprisonments.

Politicking from prison

Hafiz Sikander Malik, an independent candidate in northern Kashmir’s Bandipora district, has spent several years in prison for promoting Kashmiri independence. Now, he’s going door-to-door wearing a GPS ankle monitor, advocating for the release of fellow prisoners and trying to secure a spot in Kashmir’s 90-member legislative assembly.

“Most of our supporters are victims of prison,” says Mr. Malik, who is backed by a banned socioreligious organization that previously boycotted elections. “We want these draconian laws to be revoked. We want to get youth released from prisons. This is part of our manifesto.”

Shopkeeper Malik Nayeem ul Hassan believes a vote for Mr. Malik is a vote against “against oppression and coercion.”

He says many of Mr. Malik’s backers probably boycotted elections in the past, but times have changed. “If we don’t join that change, then we will stay behind in society,” says Mr. Hassan. “It is the need of the hour for everyone to participate in the elections.”

Sheikh Abdul Rashid, better known as “Engineer Rashid,” is also politicking on bail. Since his Sept. 11 release from Tihar prison, where he’s facing terror funding charges, Mr. Rashid has been campaigning on behalf of 34 assembly candidates who oppose Delhi’s crackdown.

The politician made headlines during India’s general election this spring when he won a parliament seat from prison, but his subsequent bail has sparked accusations that he has tacit support from the BJP, which benefits from a fragmented opposition. These allegations have sowed doubt into his base, including Mr. Bhat, the street vendor, who voted for Mr. Rashid in May.

“Rashid talks about the right to self-determination, but it’s all theatrics for elections,” he says.

And compared to the general election, when electing Engineer Rashid was seen as a bold statement against Mr. Modi and the BJP, Mr. Bhat says voters must now think more practically. How much can an assembly member really accomplish behind bars, or while out on bail?

When his district went to the polls on Sept. 25, Mr. Bhat cast his ballot instead for a candidate backed by Kashmir’s oldest party – Jammu and Kashmir National Conference – which has never allied with the BJP in regional elections, and poses the strongest threat to Delhi’s influence.

On Film

In ‘The Wild Robot,’ a 5-star fable for our AI age

“The Wild Robot” is a love story about community and intimacy. It is the quintessential fable. The wilderness might be harsh, but we don’t have to be.

In ‘The Wild Robot,’ a 5-star fable for our AI age

The new movie “The Wild Robot” may draw comparisons to “The Iron Giant,” which also featured an automated protagonist. Yet my experience with the film, which is rightfully generating Oscar buzz, took me back to another cult classic starring an android – “Bicentennial Man.”

Like the late Robin Williams’ interpretation of artificial intelligence, this wild robot, named ROZZUM unit 7134 and voiced dynamically by Lupita Nyong’o, was also designed to serve. Much like in Williams’ more physical performance, the magical moments happen when both the plot and the actor introduce humanity into a sci-fi film.

It’s a perfect movie for this technological age – fast-paced and full of skepticism. An automated delivery gone awry forces our friendly robot from the heavens to earth, into a wilderness devoid of humans. At first, the fable’s message appears to be about the ills of technology and how it can corrupt a (seemingly) peaceful animal populace. But what eventually happens is that technology becomes a mirror – devices show us our own vices and values.

Ultimately, “The Wild Robot,” which is directed by Chris Sanders and adapted from a trilogy by Peter Brown, is about life itself. It’s about our human attempts to make things better. And it’s much like the seasons, nature’s cyclical attempts to refine and refresh our mistakes. And yet love covers a multitude of sins, evidenced in the unorthodox parenthood expressed among the robot, a hungry fox (voiced by Pedro Pascal), and a gosling (Kit Connor). When the gosling, Brightbill, attempts to pronounce the robot’s given name, our machine offers a nickname: “Roz.”

As the movie shows early and often, Roz’s best ability is adaptability. She imitates various animals and species, not just to survive, but also to be social. Her efforts don’t always go to plan, but that doesn’t deter our protagonist, and it’s part of the movie’s charm. That sense of optimism not only turns a predatory fox into an unsuspecting father, but also turns the food chain from a pecking order to an organized community.

This fable’s attention to detail is breathtaking, from its crisp animated visuals to its investment in individual stories aligning together with the main plot, like birds in formation. Even Roz’s eternal optimism has a foil, in the cybernetic Vontra, whose chippy demeanor doesn’t belie her villainy, but synthesizes it. In some ways, it reminded me of Nyong’o’s role as both protagonist and antagonist in “Us.” Here, though, Vontra is voiced by Stephanie Hsu. Cheeriness can be programmed, but not humanity, nor shared experiences.

For those who are understandably skeptical of technology, especially of AI and its various incarnations, “The Wild Robot” might be a tougher sell. By movie’s end, a foreign machine and programming source has successfully integrated its way into a community. But that summation would be shortsighted. “The Wild Robot” goes to great effort to distinguish software from malware and friend from foe. When the corporation who built Roz makes its appearance, it displays the duality between altruism and overreach.

And yet all of those themes seem to pale in comparison with the relationship between parent and child, an enduring circle of life that never grows old. Certainly, an alien robot taking a gosling under its wing sounds awkward, but how many times have we been out of tune with our own children? Yet we persevere, declaring the other is doing the best they can.

“The Wild Robot,” above all else, isn’t just a life story. It’s a love story about community and intimacy, about what can be imitated, but never duplicated. It is the quintessential fable. Like any great parent, it offers lessons while remaining fun. The wilderness might be harsh, but we don’t have to be.

“The Wild Robot” is rated PG for action/peril and thematic elements.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Democracy’s tail winds in Lebanon

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

The assassination of Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah has temporarily lessened the threat to Israel’s existence. Yet the real basis of Israel’s security and regional stability may rest on a different development: the persistent democratic aspirations of Arab and Iranian citizens who challenge the theology that Hezbollah and its patrons in Tehran have promoted.

“Tehran’s pursuits and policies in the region are not ones that citizens throughout the region view positively,” observed Arab Barometer in July, based on its latest regional survey of Arab opinion. Across the Middle East, it found, few respondents agreed that “It is good for the Arab region that Hezbollah is getting involved in regional politics.”

The killing of Mr. Nasrallah has opened a moment to put Lebanon’s government back together. Prime Minister Najib Mikati has vowed to extend the military’s influence across Hezbollah’s stronghold in the south and urged lawmakers to elect a new president. That renewal of democracy has strong tail winds in the recognition already made by ordinary citizens that individual rights are inherent rather than determined by a cleric’s edict.

Democracy’s tail winds in Lebanon

The assassination of Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah on Friday achieved a strategic objective Israel had sought for nearly two decades. It diminishes at least temporarily the threat to Israel’s existence posed by Iran and its militant proxies in Lebanon, Yemen, and Gaza.

Yet the real basis of Israel’s security and regional stability may rest on a different development. Well before Mr. Nasrallah’s demise, the persistent democratic aspirations of Arab and Iranian citizens posed a growing challenge to the theology he and his patrons in Tehran have promoted.

“Tehran’s pursuits and policies in the region are not ones that citizens throughout the region view positively,” observed Arab Barometer in July, based on its latest regional survey of Arab opinion. Across the Middle East, it found, few respondents agreed that “It is good for the Arab region that Hezbollah is getting involved in regional politics.”

As a Shiite cleric who claimed to be a direct descendant of the Prophet Mohammad, Mr. Nasrallah led Hezbollah in Lebanon with a messianic zeal that is central to the beliefs of his sect. The Shiite branch of Islam is a minority in the Muslim world, but it predominates in Iran and has consequential influence in both Iraq and southern Lebanon.

Like the theocrats who govern Iran with absolute power, Mr. Nasrallah believed that strict adherence to the laws of Islam would usher in the return of Mahdi, or the Messiah. It is a “potent vision” marshaled by groups like Hezbollah and Hamas to justify violence against Israel, noted Iranian analyst Amir Toumaj in FDD’s Long War Journal.

That theological view helped Hezbollah broaden its appeal to varying degrees as Shiite and other Lebanese citizens felt frustrated by the failures of their government to provide economic opportunity or protection during periods of heightened tensions with Israel. Yet in Iran, that appeal has lost ground. Amid the violent repression of rights for women, many younger Iranians have turned to neighboring Iraq, where the most popular Shiite cleric preaches free and fair democracy without direct political control by religious figures.

Younger Lebanese share that yearning. Many blame Hezbollah for fomenting political violence and blocking democracy. As a political party with a minority of seats in Parliament, it helped derail municipal elections three times and marred 12 attempts since 2022 to choose a new president.

Against that background, Lebanese citizens are striving to rebuild governance at the grassroots through civil society. Those efforts, says Sera Saad, an urban planner in Beirut, seek to strengthen unity across Lebanon’s diverse religious communities and restore civic trust. “We’ve now seen youth take beautiful initiatives and engage with their municipalities to make their villages and cities a better place for everyone,” she told The Hague Academy for Local Governance.

The killing of Mr. Nasrallah has opened a new moment for putting Lebanese governance back together. Following a meeting with visiting French Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot in Beirut on Sunday, Prime Minister Najib Mikati vowed to extend the military’s influence across Hezbollah’s stronghold in the south and urged lawmakers to elect a new president. That renewal of democracy has strong tail winds in the recognition already made by ordinary citizens that individual rights are inherent rather than determined by a cleric’s edict.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Waiting on God for the deeper truth

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Bobby Lewis

Taking a moment to yield to God’s spiritual perspective opens us to greater harmony.

Waiting on God for the deeper truth

I was out in the mountains hiking in quite a remote area when I saw a piece of gear on the ground to the side of the trail. This was a place where only a handful of people might travel in any given year, and I thought certainly no one would come back looking for it. It also occurred to me that I could put the item to good use, and so, with no more consideration than that I put it in my pack and carried on.

Except, a little way up the trail I caught myself thinking, “It’s not stealing, or breaking a commandment; you just found it; it’s okay.” Hmmm. That made me pause and question this justifying thought in prayer.

What I find in situations where I’m justifying something, is that there is often some deeper truth at play, which God, divine Mind, is nudging me to be attentive to.

I walked on, continuing to pray, and when I felt open to listening to the answer, I asked God in prayer, “What do You want me to understand here?” The answer came immediately: “Do unto others as you would have them do to you.” Yes, the Golden Rule was the deeper truth in that case (see Matthew 7:12).

As soon as my thought was open to it, I realized that most likely a nearby rancher had lost the gear when working with their cattle, and I found a place to hang the item where they could discover it when they were next out there. Obeying God, who is infinite good, felt satisfying.

Continuing up the mountain, I could see that the pattern which occurred in that small experience was something that happens in more significant ways as well. Human thought is quick to take a position, justify it, and then defend it, all without pausing and waiting on God, as the Psalms teach us to do (see Psalms 25:5, for example).

But the thing is, God is invested in bringing the integrity, goodness, and love which characterize the Divine to light through each of us as the entirely spiritual daughters and sons of God.

In the book of Isaiah, God is recorded by the prophet as saying, “My thoughts are not your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8). How does one know God’s thoughts? I’ve found it really helps to ask, “God, what do You know of this?” Or, “How do You want me to see this?” Prayerfully asking in this way quiets limited thoughts and opens one to the spiritual goodness that the divine Mind is communicating.

To receive God’s messages, we need to listen and yield. It takes courage to trust that what God, Love, reveals will be useful, even though it may be quite different from the position we have attached ourselves to. And it takes willingness to yield to the inspiration that comes.

Putting that gear back didn’t take any particular courage or extraordinary willingness, but I could feel that God was reminding me of the value of praying even about issues that don’t seem like a big deal.

Each time we are responsive to God’s nudging and give up our personal thoughts and position about something for the deeper truth being revealed, it teaches us how to do so when the big things come up.

This yielding of personal justification is part of Christian discipleship, which the founder of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, describes in the textbook “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures”: “Christian Scientists must live under the constant pressure of the apostolic command to come out from the material world and be separate” (p. 451). The opportunity for discipleship is available to all, bringing with it limitless blessings.

In a world that can often seem hopelessly trapped in vitriol and strong personal opinions, disciples of Christ – students of the spiritual idea of God – daily find ways in their own lives to break that pattern, as Jesus did throughout his career.

What if each person were willing to move beyond surface currents and strongly held positions and really listen for what God knows and is revealing? Would we find progress in our families, communities, nations, world? Most certainly. We each have a choice moment by moment.

When we yield in prayer to divine Mind’s direction, it does make a difference. I imagine that there is a rancher somewhere in southern Colorado with a smile on her face that someone left her gear where she could find it instead of putting it in their pack. Praying about the small things matters, just as it does with the big things.

Viewfinder

China’s celebration

A look ahead

Thanks for being here to start your week. Among the stories we’re working on for tomorrow: a look at the U.S. role in deterrence and diplomacy amid fears of a widening war in the Middle East, and a report on the centennial of President Jimmy Carter’s birth against the backdrop of an America now reassessing its priorities.