- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 8 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- Election week could be just as long, and fraught, as in 2020

- Today’s news briefs

- Israeli strikes inside Iran cross a threshold. How will Iran respond?

- How Trump’s abortion policies could be felt around the world

- With Senate hopes dwindling, Democrats look to Texas

- Japan’s new PM hoped snap elections would secure grip on power. They backfired.

- The French love to hate ‘Emily in Paris.’ But they won’t let her leave.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

The election homestretch

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

My sister used to be in politics, and she said elections were all about building a narrative that would crescendo in the final days before the vote. In some ways, that same calendar applies to the Monitor, too.

In the homestretch before the United States presidential election, you’ll see us focusing on many stories that set the scene for next Tuesday – less as prognostications, more as highlighting trends and setting expectations. The hope is to help keep you focused on what’s going on beneath the noise.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

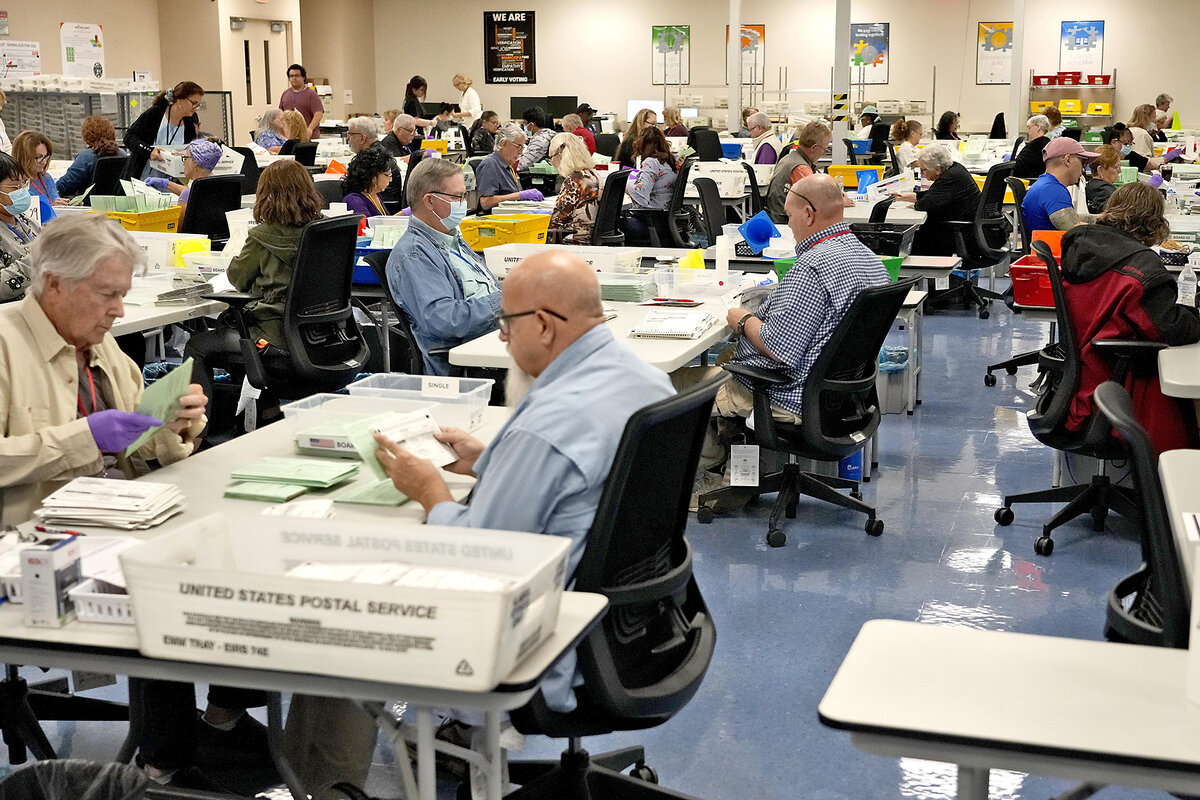

Election week could be just as long, and fraught, as in 2020

Delayed election results can open the door to suspicion and disinformation. Yet in a close election, a dayslong wait to know the winner isn’t surprising. It happened in 2020. We look at why it could easily happen this year, too.

Vote counting in the U.S. election will likely go faster this year than in 2020, thanks to improved procedures in some states and fewer people voting by mail now than during the pandemic.

But in battleground states Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Nevada – four states that could determine the presidency this year – it could take days or longer to determine who wins a close election. A major reason is slow processes for tallying mail-in votes, and the sheer number of those ballots.

Delayed results aren’t just a test of patience. They can open a door for bad-faith actors to attack the system or sow distrust.

“The window of time from when the polls close until the race is called is the largest window for mis- and dis-information and harassment and threats,” says Seth Bluestein, the Republican commissioner on Philadelphia’s election board.

Election disinformation has already picked up. On Friday, Donald Trump posted on his social media about supposed “Cheating and Skullduggery” of the 2020 election, falsehoods that the former president has continued to promote despite a lack of evidence.

Don’t be suprised, either, if the earliest-counted votes tilt more Republican than the later ones. The counties that typically take the longest to count their ballots are large urban areas, which tend to be racially diverse and heavily Democratic.

Election week could be just as long, and fraught, as in 2020

During election week 2020, Seth Bluestein never went to sleep.

Mr. Bluestein, then Philadelphia’s chief deputy election commissioner, woke up on Election Day to oversee the tallying of hundreds of thousands of votes. The next time he got some shuteye was three days later, on Friday.

“We knew that we had to continue counting, 24/7, until every ballot had been canvassed, and that’s what we did,” he says.

As he worked, he came into the crosshairs of the Trump campaign, which falsely claimed that their candidate had won the state and that something fishy was going on in Philly. After a Donald Trump surrogate criticized Mr. Bluestein by name during a press conference, antisemitic messages and death threats poured in.

“We had to get police protection outside of my house to protect my wife and kids while I was at the convention center counting ballots,” says Mr. Bluestein, who is now the Republican commissioner on Philadelphia’s election board. It took until Saturday before enough ballots were counted for news networks to call the state – and the election – for Joe Biden.

Steps could have been taken to lower the risk of a repeat scenario for 2024. But the state’s GOP-controlled legislature refused to heed bipartisan pleas to let officials process mail votes before Election Day, meaning it will still take days to tally all of those results. That could lead to another drawn-out election with no clear winner for days.

And delays leave a void for bad-faith actors to step in and attack the system.

“The window of time from when the polls close until the race is called is the largest window for mis- and dis-information and harassment and threats,” Mr. Bluestein says.

First, the good news: Vote counting will likely go faster in most states this time around. The country is no longer conducting an election at the height of a global pandemic, so fewer people are opting to vote by mail, based on early 2024 mail ballot requests and returns. Mail votes simply take much longer to count because those ballots require many additional steps of verification and preparation. And some swing states have taken steps to improve election law to speed up the vote-counting process.

But the four crucial battleground states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Arizona, and Nevada all will likely take a while to fully tabulate their returns. If the race is as close as polls suggest, that will likely leave America waiting for days to know who their next president will be, in a highly fraught election that many voters from across the political spectrum feel is an existential turning point for the country.

Election disinformation has already picked up in intensity. Last week, a video went viral purporting to show someone destroying Republican mail ballots in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a critical swing county. State and local election officials quickly showed that that video was fake – but not before it racked up hundreds of thousands of views on the social platform X. U.S. intelligence officials said Friday they believe it was a Russian disinformation effort.

Slow counting is frustrating, but it isn’t an actual problem. The challenge comes when high-profile politicians such as Mr. Trump cast aspersions on a process that, while slow, is overwhelmingly accurate. In the aftermath of the 2020 election, the former president declared victory on election night even as millions of votes remained to be counted, tried to overturn his election loss for months, and has continued to insist, with no evidence to back his claims, that he won – while refusing to promise he’ll accept the results this time.

On Friday, Mr. Trump posted on his social media about the supposed “Cheating and Skullduggery” of the 2020 election – while warning about 2024. “WHEN I WIN, those people that CHEATED will be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the Law, which will include long term prison sentences so that this Depravity of Justice does not happen again,” he posted.

“If Donald Trump perceives that he is losing … I think we’re likely to hear him declare victory on election night and spread lies about the election,” says David Becker, a former Justice Department Civil Rights Division attorney who heads the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research.

The slow climb up the “Blue Wall”

Forty-three states allow county election officials to begin pre-processing mail ballots before Election Day: checking to make sure the ballots are valid, removing them from envelopes, smoothing them out so they can go through tabulating machines (but not counting the votes themselves). That lets those states move vote-counting along at a faster pace on Election Day.

But Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are exceptions, which slows downvote counting in two states that have been pivotal in the past two presidential elections.

On top of that, neither state has in-person early voting, meaning the only way to vote before Election Day is by absentee ballot. (Wisconsin has “in-person absentee voting” where people can vote absentee ballots at election sites). That means those states have many more absentee ballots to process than other states.

Former Kentucky Secretary of State Trey Grayson, a Republican, says it was “really unfortunate” that Pennsylvania didn’t change its law to allow pre-processing of ballots.

“When you start having a lot of people vote by mail, you really do need the pre-process. Otherwise, your results aren’t going to come in as quickly,” he says.

In Pennsylvania, Republicans refused to pass legislation allowing pre-processing unless Democrats first expanded the state’s voter identification requirements. In Wisconsin, a bill to allow pre-processing passed the GOP-controlled Assembly with bipartisan support but was stonewalled by hardline Republicans in the state Senate.

The counties that tend to take the longest to count their ballots are invariably large urban areas, which tend to be racially diverse and heavily Democratic – places like Philadelphia and Milwaukee. That’s largely because so many more votes come in that it takes longer to accurately tabulate them all. But it feeds into racially tinged conspiracy theories that local Democratic machines are rigging the vote. Milwaukee has new vote-counting machines that can tabulate 100 ballots a minute, a big improvement over the old machines that could only process seven ballots a minute in 2020 – but the main bottleneck is physically verifying the votes and preparing them for the machines.

“If Milwaukee gets their results in by 2 a.m. [CST], I’d be delighted,” says Ann Jacobs, a Democrat and the chair of the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission.

“We’re going to have late results that will result in significant numbers coming in all at once – and that significant number all at once will be from largely Democratic-leaning communities … our larger urban areas,” she continues. “It’s math.”

Ways that counting has improved since 2020

Michigan used to be in the same boat. But the state is likely to count its votes faster this time around. In 2022, voters passed a state ballot initiative that is allowing in-person early voting for the first time. While early counts of in-person early voting have been relatively low, voters who cast their ballots that way rather than through the mail make it easier on county clerks to tally the votes. On top of that, Democrats who control the state’s legislature and governorship passed a law allowing pre-processing of ballots, meaning they’ll be able to move mail votes much faster.

In Georgia, which has always counted its votes relatively quickly, lawmakers and elected officials have put a major emphasis on speeding up the count – Republican Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger told the Monitor last month that the goal is “free, fair, and fast.”

State courts also struck down a bevy of controversial last-minute election rule changes pushed through by hardline conservatives on the state election board, including one that would have slowed down the state’s vote count by forcing poll workers to hand-count the number of ballots cast in every county on Election Day.

We’re likely to see the same “red mirage” as last time in a number of states that process their mail ballots later than in-person ballots. Preliminary early voting numbers across various states show that registered Democrats are still voting by mail at a much higher rate than Republicans this election, though in smaller numbers than 2020. In the states like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where those Democratic-leaning batches are counted last, that means early numbers will appear better for Mr. Trump than the final result. And in states like Nevada and Arizona where mail voting is dominant, it will simply take much longer to tabulate ballots, something that’s been true long before the Trump era.

How the West was mailed

Most Western states of all political persuasions have adopted predominantly mail voting elections over the past two decades, making their vote-counting take longer.

Hotly contested Arizona is a heavily vote-by-mail state that for decades has taken a long time to count its ballots – long enough that it has regularly taken days and even weeks to know who won close elections. Former President Trump has used that slow process to cast doubt on the results for years. In 2018, as Republicans were on their way to losing a close Senate race during vote-counting after Election Day, Mr. Trump falsely claimed “electoral corruption.”

Arizona officials, unlike workers in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, can preprocess mail ballots. But they can’t begin processing ballots dropped off on Election Day until polls are closed. And since many voters are in the habit of hanging onto their ballots until the last minute in the state, it leads to a significant slowdown.

Nevada is also likely to take a while. As in 2020, it has sent mail-in ballots to every active registered voter in the state, which will likely increase mail voting over in-person voting. Nevada also counts mailed ballots received up to four days after the election, so long as they were mailed by Election Day.

“Depending on margins [of victory], my expectation would be Arizona and Nevada are the states that we’re waiting on the longest to find out a call about the election,” says Derek Tisler, a counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice’s Elections and Government Program.

He says that if the margins of victory in key states are as close as they were in 2020, it will likely take about as long as it did four years ago to know who won. If the race is significantly closer, “it will likely be weeks before we know who won the presidential election.”

And that worries him.

“What we saw in 2020,” he says, “is the longer the time is between when voters finish casting their ballots and when we know who won the election, the more opportunity there is for disinformation about elections to spread.”

Today’s news briefs

• Georgians protest: Tens of thousands of Georgians mass outside the nation’s Parliament, demanding the annulment of the weekend parliamentary election that the president has alleged was rigged with the help of Russia.

• Cease-fire proposal: Egypt’s president says his country has proposed a two-day cease-fire between Israel and Hamas during which four hostages held in Gaza would be freed.

• China family planning: China outlines steps to boost the number of births after two consecutive years of a shrinking population. The State Council called for efforts to build “a new marriage and childbearing culture.”

• Philippines storm: Residents of northern and central provinces in the Philippines are picking up the pieces following one of the deadliest storms to hit the country this year.

Israeli strikes inside Iran cross a threshold. How will Iran respond?

In over a year of conflict between Israel and Iran’s militia allies, a key brake on a regional war has been each side’s fear of what the other could do. Does Israel’s latest strike mean that brake is failing?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

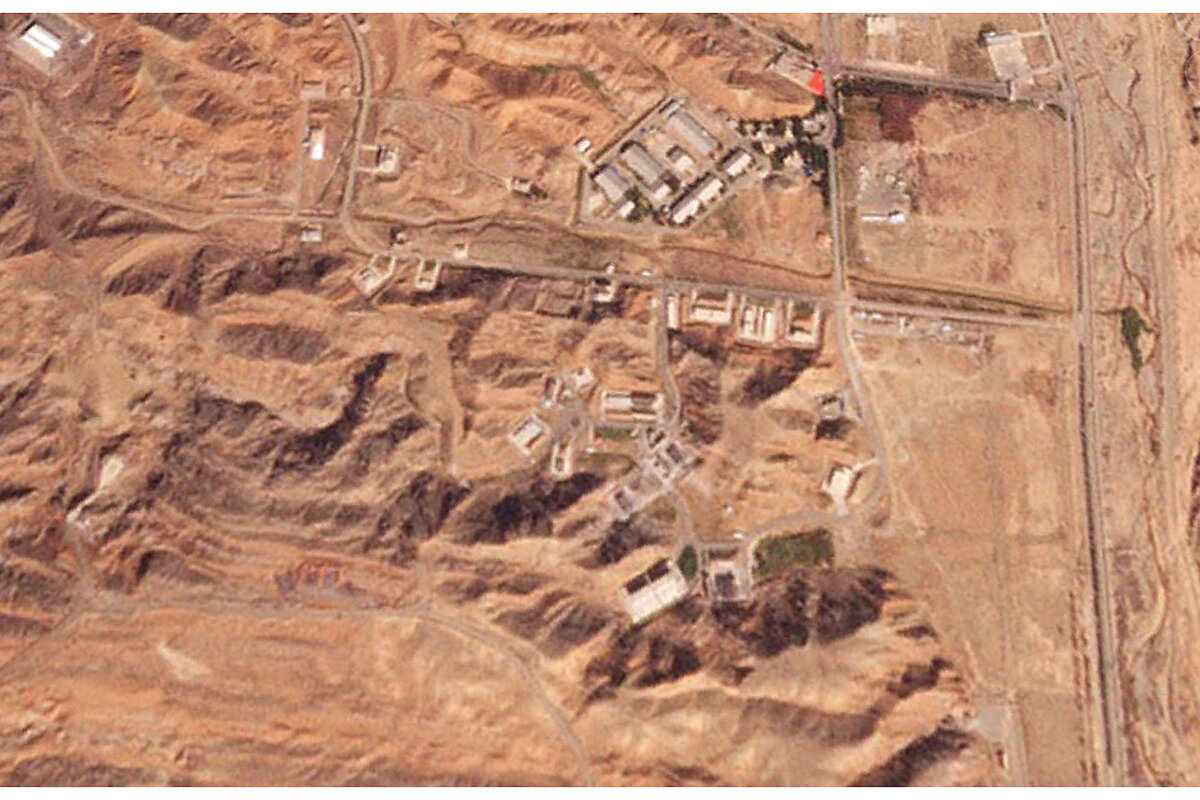

Israel’s unprecedented strikes Saturday against 20 military targets inside Iran show how far and how swiftly long-standing deterrence calculations are changing across the Middle East after over a year of escalating conflict.

The Iran-Israel conflict was once limited largely to a shadow war. It was marked on Israel’s side by assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, sabotage, and computer virus attacks, and on Iran’s side by the buildup of allied militias ready to target Israel.

Now Iran and Israel are openly striking each other’s territory in blows that only recently seemed unthinkable.

Early Saturday, Israel knocked out Iran’s four remaining Russian-made S-300 surface-to-air missile batteries and key radar arrays, apparently paving the way for possible future strikes. In the past year, Israel has deeply damaged Hamas and now has gone after Hezbollah.

“Iran’s deterrence is in ruins,” says Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group in Washington.

Nevertheless, the view from Tehran is that Iran’s deterrence calculations with Israel still largely hold, says Hassan Ahmadian at the University of Tehran, adding that some say Iran’s mistake was to not hit back at Israel faster for previous strikes.

“That’s why I am quite sure Iran will do something directly against Israel,” he says.

Israeli strikes inside Iran cross a threshold. How will Iran respond?

Israel’s unprecedented strikes Saturday against 20 military targets inside Iran, its archfoe, show how far and how swiftly long-standing deterrence calculations are changing across the Middle East after more than a year of escalating conflict.

The Iran-Israel conflict was once limited largely to a shadow war. It was marked on Israel’s side by assassinations of Iranian nuclear scientists, sabotage, and computer virus attacks, and on Iran’s side by the buildup of allied militias, from Lebanon and Gaza to Yemen, ready to target Israel.

Now Iran and Israel are openly striking each other’s territory in blows that only recently seemed unthinkable.

Before dawn Saturday, Israel struck Iran’s air defense systems, apparently paving the way for possible future strikes by knocking out Iran’s four remaining Russian-made S-300 surface-to-air missile batteries and key radar arrays, which protected important energy installations.

Israel also targeted sophisticated industrial mixing machines used to blend solid fuel for Iran’s arsenal of ballistic missiles – which would be necessary to replace missiles fired at Israel.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel “hit hard Iran’s defense capabilities and its ability to produce missiles that are aimed at us.” Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said the strikes “should neither be magnified nor downplayed” and did not mention retaliation, though other officials did.

Cycle of retaliation

Israel struck Saturday in response to an Iranian barrage of some 180 missiles and drones that rained down on Israel on Oct. 1, with dramatic scenes of night skies full of incoming rockets aimed at Israeli military air bases and Mossad headquarters.

Iran’s barrage was largely stopped by Israeli air defenses, with no loss of Israeli life, and was itself retaliation for previous Israeli attacks and high-profile assassinations against Iranian allies, including Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran, and Hezbollah chief Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut.

Both sides downplay the impact of their enemy’s direct strikes against them, while boasting of the impact of their own salvos.

But the multiple, unprecedented exchanges are changing strategic calculations. They have demonstrated Israel’s ability so far to aggressively dominate the escalation – while drawing Iran into a more conventional fight, where Israel has the advantage – even as Iran’s pillars of deterrence have been shaken.

On top of their direct battle, Israel has deeply damaged Hamas during a year of fighting that has laid waste to Gaza and left more than 40,000 Palestinians dead. And it has gone after Hezbollah and its much-vaunted missile arsenal in Lebanon with thousands of airstrikes and a ground incursion.

“Iran’s deterrence is in ruins,” says Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group in Washington. He notes that the Islamic Republic “has never been as vulnerable” since the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s, when missiles last landed in the capital, Tehran.

“Iran’s regional shield, Hezbollah, has been cracked. Its Russian-made internal shield has been decimated. And its sword made of ballistic missiles has been dulled by Israel’s multilayered aerial defense system,” says Mr. Vaez.

The result presents an “impossible dilemma” for Ayatollah Khamenei about how to respond, he says.

“On Khamenei’s right shoulder sit the hawks who warn of a Lebanon scenario, in which lack of response only encourages Israel to escalate further,” says Mr. Vaez. “On his left shoulder sit the more pragmatic forces of Iranian politics who warn against playing into Israel’s hands and giving it an opening to destroy the country’s strategic assets.

“Now that the red line of overt and direct strikes on Iran’s soil has turned pink, Israel is playing to its own strength and exploiting Iran’s conventional weakness,” he adds.

The Oct. 7 attack

The current test for Iran’s deterrent strategy began on Oct. 7, 2023, when Hamas mounted a cross-border attack from Gaza into Israel. Iran praised the action as an act of legitimate Palestinian resistance, which left 1,200 Israelis dead and 250 held hostage in Gaza.

The next day, the Lebanese Shiite militia Hezbollah opened what it called a “support front” by launching rocket attacks on northern Israel, triggering exchanges that quickly displaced 65,000 Israelis and 100,000 Lebanese from border areas.

Throughout the conflict, Iran – beset by its own political and economic upheavals at home – made clear its desire to avoid a wider war. But incremental escalation finally led to an Israeli strike on an Iranian diplomatic compound in Damascus, Syria, which killed senior Iranian military officials and prompted Iran’s first direct barrage against Israel, with 300 missiles and drones in mid-April.

They were mostly shot down by Israel and the United States, and that mild damage – combined by the lack of immediate Iranian retaliation for Mr. Haniyeh’s assassination – set the stage for an audacious series of attacks against Hezbollah, which began Sept. 17 with the explosion of thousands of pagers.

Nevertheless, the view from Tehran is that Iran’s deterrence calculations with Israel still largely hold, despite the escalation into direct conflict, says Hassan Ahmadian, an assistant professor at the University of Tehran.

“The impression in Iran is that the ‘Axis of Resistance’ is doing what it was supposed to do, and it is effective, though the damage has been big to Hamas, to a lesser extent Hezbollah. But still, it’s functional; it’s working,” says Dr. Ahmadian.

“Of course the assassination of Haniyeh and Nasrallah might have given the impression to Netanyahu and the Israelis, ‘Well, we have a free hand now; let’s go for the big guy [Iran].’ But then I think they are very fast, very soon, hitting the hard reality that it’s not gone; Hezbollah is doing what it’s doing.”

Indeed, Hezbollah has continued firing rockets daily into Israel, including 90 on Sunday, and its fighters have sought to stop the Israeli advance on the ground.

Iran’s delayed response

With the missile barrages and airstrikes, the Israelis and Iranians “are repeating the same message” to the other side “that we can reach you,” says Dr. Ahmadian. “So it’s either back to the indirect, gray zone [of the shadow war], which Iran has preferred for decades, or it leads to a tit-for-tat that has the potential of spiraling into something bigger.”

Shaping Iran’s response to Israel’s attack Saturday may also be the lesson learned from Iran’s delayed response to the assassination of Mr. Haniyeh, who was in Tehran for the inauguration of Iran’s new pragmatic-leaning president, Masoud Pezeshkian, on July 31.

The timing of Iran’s retaliation may also be an integral part of maintaining deterrence. In early August, when questions were being raised about the lack of a swift Iranian response, Dr. Ahmadian noted in a post on social platform X that failure to act decisively would lead to “open season on Tehran and its allies.”

“The Israelis received that inaction as a sign of weakness, and that’s why Netanyahu moved into Lebanon,” says Dr. Ahmadian. “That mentality is still very strong in Iran. ‘We didn’t do it [retaliate] after Haniyeh; they moved a step closer, and they did something bigger. Now they did something directly against Iran. If we don’t do it, will they move closer to Iran, or do something bigger?’

“I think that presses hard on what Iranian leadership circles are thinking about – they have that experience in mind,” he adds. “That’s why I am quite sure Iran will do something directly against Israel.”

How Trump’s abortion policies could be felt around the world

Republican presidents have long withheld U.S. aid from groups in developing countries that practice abortion. If Donald Trump wins the election, he is likely to impose harsher restrictions that will negatively impact broader health care, workers in the sector fear.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The impacts of America’s election result will be felt worldwide. And in Madagascar, family planning expert Lalaina Razafinirinasoa is afraid that a Donald Trump victory could herald potentially fatal consequences.

One of Mr. Trump’s first acts when he became president in 2017 was to do away with all U.S. funding for any group that performed or promoted abortions, even if the money was being spent on other services such as birth control or prenatal checkups.

The Madagascar branch of the Marie Stopes family planning charity, which Ms. Razafinirinasoa heads, lost U.S. funding for birth control. Less birth control meant more unwanted pregnancies and so actually led to more abortions, she says. Because abortion is completely illegal in Madagascar, many of these procedures were unsafe, and potentially fatal.

A global study published in the journal Lancet estimated that in countries heavily reliant on U.S. family planning aid, including Madagascar, abortions increased by 40% during the Trump and Bush administrations, which both imposed what critics call the “gag rule.”

“We are trying not to panic, because what can we do?” says Jedidah Maina, the executive director of a Kenyan health nonprofit. The U.S. election result “could change our lives,” she points out, “but we don’t even have a vote.”

How Trump’s abortion policies could be felt around the world

As the U.S. presidential election approaches, Lalaina Razafinirinasoa cannot shake a frightening thought. If Donald Trump wins, he will likely impose policies that could lead to the deaths of women she knows.

After all, it has happened before.

One of Mr. Trump’s first acts when he became president in 2017 was to sign an executive order cutting off all American health aid to organizations that “perform [or] actively promote abortion.”

The ban was not intended to stop U.S. money from being used on abortions; that has been forbidden for 50 years. Rather, it was meant to keep American aid dollars out of the hands of pro-abortion-rights groups more generally. That’s whether they planned to use the money to fund birth control, give HIV tests, or treat malaria – a vastly expanded version of a policy enacted by every Republican administration since Ronald Reagan.

Ms. Razafinirinasoa runs the Madagascar branch of MSI Reproductive Choices (formerly Marie Stopes International), a family planning charity that chose to give up $30 million a year in U.S. funding rather than accept the new conditions.

That forced Ms. Razafinirinasoa’s team to cut outreach programs that brought birth control to the island’s poorest and most remote corners, a decision that still haunts her.

“We’ll never know exactly how many women we lost,” Ms. Razafinirinasoa says. Globally, one peer-reviewed study estimated the U.S. policy led to the deaths of more than 10,000 women and nearly 100,000 children, primarily as a result of decreases in the quality of their medical care.

So now, as Ms. Razafinirinasoa and other global family planning advocates watch the election approach from thousands of miles away, it feels close and urgent.

“We are trying not to panic, because what can we do?” says Jedidah Maina, the executive director of the Trust for Indigenous Culture and Health, a Kenyan health nonprofit. “It could change our lives, but we don’t even have a vote.”

The luxury of choice

When Ms. Razafinirinasoa became the director of Marie Stopes Madagascar in 2015, she often found herself brushing up against the lives she could have lived.

Visiting remote, rural villages like the ones where her parents grew up, she met pregnant 11-year-olds and hungry women struggling to feed a half-dozen emaciated children, all of them far too small for their age. “I’m just tired of giving birth,” she remembers one mother of seven quietly confessing.

Ms. Razafinirinasoa knew that only a razor-thin line separated her life from theirs. In Madagascar, whose international image is of white sand beaches and wide-eyed lemurs, the average woman is a mother of five, and a third of girls give birth before the age of 19. Nearly half the population is chronically hungry.

“Not many people have the luck I did,” she says. Her parents moved to a city and sent her to school. But another fundamental part of that “luck” was also that she got to decide if and when she had children. Everyone “should at least be able to make their own choice on their reproductive life,” she says.

The World Health Organization agrees. When women control their fertility, it concludes, they are healthier, more educated, and more economically independent. And so are their children.

Over the past four decades, the number of women worldwide using modern contraceptives has doubled. In many places, American aid has played a major role in this story. But the help comes with strings attached.

Since the 1980s, American funding for family planning has been deeply politicized. Each time a Republican becomes president, they instate the Mexico City Policy, an executive order barring American funding for foreign organizations that do abortion-related work. Each time a Democrat takes office, they repeal it.

Historically, the Mexico City Policy, which critics call the “gag rule,” applied only to funding earmarked for family planning. But in 2017, Mr. Trump announced he was expanding it to all American global health aid, then around $9 billion annually.

Suddenly, recipients had to choose between providing legal abortions and getting funding for things like malaria tests, HIV medications, and child nutrition. “When we design programs” for these services, “we don’t intend to fund the abortion industry,” explained the White House in a statement to The Washington Post at the time.

Meanwhile, in countries like Madagascar, where abortions are not allowed even when they are needed to save the mother’s life, groups still lost funding if their parent organization supported or provided them elsewhere.

“I don’t know that people are always aware that this policy has enormous impact even where abortion is highly restricted,” says Sara Casey, an assistant professor of population and family health at Columbia University.

Counterintuitive consequences

At the end of Mr. Trump’s presidency, Dr. Casey led a study of the policy’s impact in Kenya, Madagascar, and Nepal. In all three countries, her research concluded that the policy made it harder for women and girls to access family planning. Organizations receiving American funding also often aggressively self-policed, overapplying the policy out of worry that they might accidentally overstep an unseen line.

In Madagascar, the researchers found the policy’s effects were especially far-reaching, in part because the United States provided nearly 90% of all family planning aid. That meant that when MSI Reproductive Choices and other organizations cut their programs, many women lost their only access to free birth control.

One woman described scrambling to find ways to pay $0.65 for an injectable contraceptive at a private pharmacy, until one day she couldn’t anymore. “And now I’m pregnant when I didn’t want to be,” she said.

Globally, experts estimate that despite the policy’s purported aims, it actually increased the number of abortions being performed in many countries. A study published in the journal Lancet estimated that abortions increased by 40% during the Trump and Bush administrations in counties that relied heavily on U.S. family planning aid, including Madagascar. Although the study did not analyze the causes of this increase, the authors posited it could be because the policy restricts access to contraceptives, leading to more unwanted pregnancies.

Ms. Razafinirinasoa says the effects of those years still reverberate. Though Marie Stopes Madagascar eventually made up some of its lost funding, the scope of its work remains narrower than in 2016. Another Trump administration would likely mean more cuts, with a possible further extension of the Mexico City Policy to include emergency humanitarian aid.

Ms. Razafinirinasoa knows who would suffer most from those policies. “This is about equity,” she says. When aid goes away, “The poorest people are always the first ones who will die.”

With Senate hopes dwindling, Democrats look to Texas

Changing demographics have stirred speculation for years about Texas turning purple. But as Democrats look to this massive Southwestern state as their best chance to maintain Senate control, they may be disappointed again.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

On Friday, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris took their campaigns not to familiar battleground states like Pennsylvania or Michigan – but to Texas.

Both presidential nominees used the appearances to promote their key issues but also to boost candidates in a critical Senate race.

A Republican Senate candidate hasn’t lost in Texas since 1988, but Sen. Ted Cruz came close in 2018. Now Colin Allred, a congressman and former professional football player, hopes to oust him in what would be one of the biggest upsets of the election.

As demographic changes have helped turn states like Arizona and Nevada into political battlegrounds, many analysts say Texas is heading in the same direction.

Texas is now more important to Democrats’ electoral hopes than ever. Ms. Harris’ party holds a one-seat majority in the Senate but is defending 19 seats this cycle, including several in states that Mr. Trump won by big margins in 2020. Democrats will likely need to flip a GOP seat to retain control.

“Texas has emerged as their best chance to flip a Republican-held seat,” says Jessica Taylor, an editor for The Cook Political Report. “It’s been trending Democrat recently, but is it there yet? I don’t think so.”

With Senate hopes dwindling, Democrats look to Texas

Just 11 days before an election expected to hinge on a handful of swing states, both major party presidential nominees descended on a state that, while not a presidential battleground, could be mighty important.

On Friday, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris took their campaigns to Texas – Mr. Trump in Austin and Ms. Harris in Houston.

While both candidates used the appearances to amplify base issues – border security for Mr. Trump and abortion for Ms. Harris – they also aimed to give late boosts to candidates in what has become a critical U.S. Senate race.

A Republican Senate candidate hasn’t lost in Texas since 1988, but Sen. Ted Cruz, considered an abrasive conservative even by some members of his own party, came close in 2018. Now, Colin Allred, a Dallas-area congressman and former professional football player, hopes to oust him in what would be one of the biggest upsets of the election.

As demographic changes in the Southwest have helped turn states like Arizona and Nevada into political battlegrounds, many analysts say that the Lone Star State is heading in the same direction. Still, while each election has brought fresh buzz that Republican dominance here is ending, that buzz has routinely evaporated on election night.

There is little evidence that this year will be any different, but Texas is now more important to Democrats’ electoral hopes than ever before. Ms. Harris’ party, which currently holds a functional one-seat majority in the Senate, is defending far more seats than Republicans this cycle, including several in states Mr. Trump won by big margins in 2020. With West Virginia all but certain to elect a Republican and Montana looking increasingly likely to as well, that means Democrats will need to flip a GOP seat to retain control.

The focus has become Texas. It’s still a long shot, experts say. But polls show Representative Allred is within striking distance – and as such, has become Democrats’ best hope to hold the Senate and their next great hope to turn Texas purple.

“Texas has emerged as their best chance to flip a Republican-held seat,” says Jessica Taylor, the Senate and Governors editor for the Cook Political Report. “It’s been trending Democrat recently, but is it there yet? I don’t think so,” she adds. “Those last few points in Texas are just incredibly hard to get.”

Democrats’ “last, best hope”

Six-year terms for senators help make each election map different from the last. The 2024 map is one that national Democrats have been fearing for a long time.

“We knew years ago that the map was going to be absolutely brutal going into this cycle,” says Jim Manley, a Democratic strategist. “So far that’s proving to be the case.”

Democrats ended six years of GOP control of the Senate in 2020, and two years later, won a 51-49 majority. But now the blue team is defending 19 seats, plus four held by independents who caucus with them. Republicans, meanwhile, are defending 11 seats, all in reliably red states.

Polls suggest that the GOP is likely to flip two seats, replacing retiring Sen. Joe Manchin in West Virginia and ousting three-term incumbent Sen. Jon Tester in Montana.

Democratic incumbents are also facing tough races in Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

Only a few states have polls suggesting that Republican incumbents may be remotely in danger. In the campaign’s final weeks, Democrats are pouring money into two of them: Texas and Florida.

Senator Cruz leads Mr. Allred by just one point, according to a poll released last week by Emerson College and The Hill. Other recent polls have the two-term Democrat slightly further behind. But Mr. Cruz has consistently been one of the least popular Republicans in Texas.

”He’s a very controversial figure, always has been, always will be,” says Whit Ayres, a GOP pollster based in Virginia.

Mr. Allred, a former professional football player turned civil rights lawyer, has used his opponent’s disagreeable reputation to build a big fundraising advantage. The Democrat has trumpeted his bipartisan record, and he’s attacked Mr. Cruz’s support for the state’s abortion ban. Mr. Allred has also highlighted his opponent’s infamous family vacation to Cancun, documented by reporters, during a deadly winter storm in 2021 that killed hundreds and left millions of Texans without power for days. When he returned, Mr. Cruz said the trip “was obviously a mistake.”

As he has campaigned, the Republican has highlighted his own burgeoning bipartisan record, and criticized his opponent on border security and transgender issues.

All told, Texas “is the last, best hope Democrats have” for holding the Senate, says Brandon Rottinghaus, a political scientist at the University of Houston. “Polling is close, you have a turbocharged electorate ... and Ted Cruz remains uniquely unliked.”

That may still not be enough, he continues. “But it’s worth the investment now.”

Not blue, but more competitive

It may seem like a Hail Mary this year, but Democrats’ longer-term focus on Texas is understandable. For one, the state’s 40 Electoral College votes are essential to Republican presidential hopes. But the state is also becoming more competitive.

Demographic changes that have made the Southwest politically winnable for Democrats – namely a declining white population and a growing, young Hispanic population – are also unfolding in the Lone Star State. The state’s Republican margin of victory has narrowed in the past two presidential elections, and new voter registrations hit a record high this year.

But the momentum has yet to translate to statewide victory for Democrats.

In 2016, Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton said her campaign “could win Texas.” She lost to Mr. Trump by nine points. Two years later, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke’s energetic, grassroots campaign to unseat Mr. Cruz ended with a less-than-three-point defeat. While Mr. Cruz himself had said that Texas would be hotly contested in the 2020 election, both Mr. Trump and GOP Sen. John Cornyn won comfortably.

“I’ve been promised Texas turning blue for at least six to eight years, and it hasn’t happened yet,” says Mr. Manley, the Democratic strategist who spent over two decades working in the Senate.

“It’s reasonable” to think it will happen, he adds, “It’s maybe just not going to happen as soon as some are suggesting.”

Groundwork for the future?

One factor, experts say, is that Texas is fundamentally more conservative than states like Nevada and Arizona. Indeed, while the state’s urban centers have been growing bluer, the Hispanic population has been shifting in the GOP’s direction.

Texas is also much bigger, making it more difficult – and much more expensive – to build campaign infrastructure and name recognition for candidates. To date, the Democratic Party hasn’t done much to change that.

“They’re paying for ads, exposure, canvassing. They’re not investing in physical things that might build infrastructure for the future,” says Dr. Rottinghaus, the University of Houston political scientist, referring to the development of volunteer networks, fundraising resources, and slates of quality candidates for local and county elections around the state.

This contrasts with how the GOP wrested the state from Democratic control in the late 20th century. When John Tower was elected to the Senate in 1961, he became the first Republican to win statewide office since Reconstruction, but it took another three decades for the GOP to gain proper traction in the state.

“You don’t go from being noncompetitive at the statewide level for cycles and cycles [to] all of a sudden being very successful,” says Matt Mackowiak, a Republican strategist in Texas.

“It’s clear [Democrats] are building something. Are they building it fast enough? Are they building it to make it strong enough to really break through? ... It doesn’t seem that way to me,” he adds.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Oct. 25, the date of initial publication, to reflect that Trump and Harris events in Texas occurred as planned.

Japan’s new PM hoped snap elections would secure grip on power. They backfired.

In Japan, the long-ruling party’s dramatic loss in a parliamentary election underscores the public’s growing frustration with its leaders, and has plunged the country into political uncertainty.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

By Takehiko Kambayashi Contributor

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior coalition partner lost their parliamentary majority in snap elections Sunday, their worst election results in 15 years.

Now Prime Minister Ishiba Shigeru, who inherited the scandal-wracked LDP just a month ago and called these elections in an attempt to rebuild public trust, must find a way to scrap together a stable government.

Speaking at a news conference on Monday, he vowed to “humbly accept” the “extremely harsh verdict,” and to carry out fundamental reforms within the party.

But many analysts believe his days are numbered. A vocal critic of LDP colleagues, Mr. Ishiba lacks a strong base of support within his party, and the election loss will further weaken his nascent government. Some predict a new period of “revolving door leadership,” like that seen from 2006-2012, when Japan had a new prime minister every year.

“The election result almost guarantees a chapter of political instability in Japan with multiple political parties seeking power,” says Nicholas Szechenyi, vice president of the Geopolitics and Foreign Policy Department at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. Mr. Ishiba “likely squandered his opportunity to lead the nation.”

Japan’s new PM hoped snap elections would secure grip on power. They backfired.

This was Ishiba Shigeru’s first major test as Japan’s prime minister, and it didn’t go as he hoped.

In Sunday’s snap elections, the long-ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and its junior coalition partner Komeito party lost their majority in the House of Representatives, marking the LDP’s worst showing in 15 years.

Now the administration of Mr. Ishiba, who inherited the scandal-wracked LDP just a month ago after an internal party election, must find a way to scrap together a stable government.

Speaking at a news conference on Monday, a grim-looking Mr. Ishiba vowed to “humbly accept” the “extremely harsh verdict,” and to carry out fundamental reforms within the party. “The Japanese people expressed their strong desire for the LDP to do some reflection and become a party that acts in line with the people’s will,” he said.

But many analysts believe his days are numbered. As a vocal critic of LDP colleagues, Mr. Ishiba lacks a strong base of support within his party, and the election loss will further weaken his nascent government. Some predict a new period of “revolving door leadership,” like that seen from 2006-2012, when Japan had a new prime minister every year.

“The election result almost guarantees a chapter of political instability in Japan with multiple political parties seeking power,” says Nicholas Szechenyi, vice president of the Geopolitics and Foreign Policy Department at the Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS) in Washington.

Mr. Ishiba “likely squandered his opportunity to lead the nation,” he adds.

Ruling party rebuked

Public frustration with the LDP is rooted in the party’s recent slush fund scandal, which came at a time when many Japanese are caught between stagnant wages and rising prices. The revelation that party factions were illegally pocketing campaign money tanked Cabinet approval ratings and led to the resignation of Mr. Ishiba’s predecessor, among other LDP lawmakers.

Then, Mr. Ishiba – a moderate lawmaker and former defense minister who has vowed to revitalize Japan’s rural regions – took the reins. He immediately called for snap elections, a year earlier than legally mandated, to “win public confidence.”

That plan backfired, say political analysts. Indeed, in the lead-up to the election, the prime minister was “sucked into the outdated characteristics of the LDP,” says Yamaguchi Jiro, political science professor at Hosei University in Tokyo, including backpedaling on some key policies in order to appease party heavyweights.

He stopped talking about creating an Asian version of NATO, and has flip-flopped on raising interest rates.

Delivering a further blow to the prime minister just four days before the elections, the Shimbun Akahata, a daily newspaper of the Japanese Communist Party, revealed that the LDP had given 20 million yen ($131,000) to local chapters headed by candidates involved in the slush fund scandal – candidates that Mr. Ishiba had recently announced would not be endorsed by the LDP.

Though the prime minister said the money was provided to strengthen local branches, not to the candidates themselves, critics slammed the LDP for, in effect, financially supporting the scandal-tainted candidates.

Of the 48 candidates implicated in the scandal, 28 lost their parliament races.

New political landscape

Altogether, the LDP lost more than 50 seats. Meanwhile, the country’s main opposition party, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, made significant leaps, increasing their seats from 98 to 148. But Japan’s opposition remains deeply fragmented, says Tamura Shigenobu, a Tokyo-based political analyst who has worked for 16 prime ministers.

He expects the LDP-led coalition to team up with two small parties – Sanseitō and the Conservative Party of Japan, which won three seats each – and then look to the Democratic Party for the People (DPP) for the last 12 seats needed to regain control of the 465-member lower house.

DPP leader Tamaki Yuichiro has said he has no intention of joining the ruling coalition, but suggested that his party could work with the coalition on an individual policy basis. Either way, these messy coalition politics will hinder the incoming government’s ability to enact transformative policy, and force Mr. Ishiba to compromise on major issues, including how money is handled in politics.

This is all assuming Mr. Ishiba stays in power. While Mr. Ishiba has signaled his intent to stay on as prime minister, it’s possible that the LDP will use this election to give him the boot before next year’s upper house elections, possibly kick-starting a period of revolving door leadership.

“Another period of political instability in Japan would presumably generate angst” in Washington based on painful memories of the now-defunct Democratic Party of Japan’s 2009-2012 tenure, says Mr. Szechenyi, who serves as senior fellow with the Japan Chair at CSIS. The party “had no governing experience and performed miserably for most of its three subsequent years in power,” he says.

After the LDP retook power in 2012, the late premier Abe Shinzo brought political stability and built broad consensus on Japan’s approach to foreign policy, including strengthening defense capabilities and developing a strong alliance with the United States, adds Mr. Szechenyi.

“A string of short-term governments would not yield radical changes in Japanese foreign policy,” he explains. “But it would affect Japan’s capacity to implement its strategic objectives, which could stunt some of the recent momentum for bolstering bilateral ties. Japan’s goals are clear, but it could take some time to find a new leader strong enough to carry the ball forward.”

The French love to hate ‘Emily in Paris.’ But they won’t let her leave.

“Emily in Paris,” the Netflix hit series, skewers French foibles and mines antiquated French stereotypes. And the French cannot get enough of it – especially now that there is talk of Emily moving to Rome.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

French President Emmanuel Macron is a busy man. But he has made time for Emily.

That would be “Emily in Paris,” the cult Netflix series about an overly enthusiastic, workaholic American who lands her dream job in Paris. But there are hints in the script that Emily might move to Rome.

“We will fight hard. And we will ask them to remain in Paris!” Mr. Macron said in a recent interview with Variety magazine. “‘Emily in Paris’ in Rome doesn’t make sense.”

The series is one that the French love to hate; through the titular character’s epic cultural fails, viewers get a dose not only of the myriad ways in which American tourists offend Parisians, but also of every French stereotype you could imagine.

“I’ve watched the entire series even if it’s not highbrow,” says Agathe, a Parisian who works at Universal Music next door to the restaurant where many of the “Emily in Paris” scenes are filmed. “It’s a guilty pleasure.”

The French might be sad if Emily leaves for Italy, but Americans in Paris are unlikely to shed any tears; many of them have had enough of the Chicago native’s absent-minded cultural blunders.

Among them is Emily Omier, an American tech consultant. “Every conversation is the same,” she says. “‘Oh, your name is Emily? Like “Emily in Paris”!’ I just say, ‘Yeah, it’s me.’”

The French love to hate ‘Emily in Paris.’ But they won’t let her leave.

I’d never seen so many red berets in my life. But there they were: five young tourists, all wearing the iconic French hat on a blustery October day. Cellphone cameras at the ready, they stood, one by one, not at the Eiffel Tower or the Pantheon a few steps away, but in front of a basic brown door at 1 Place de l’Estrapade.

But this isn’t just any door. This is where “Emily in Paris” lives.

Now in its fourth season, the hit Netflix show features Emily Cooper (played by Lily Collins), an overly enthusiastic, workaholic Chicago native who lands her dream job at a Paris-based marketing firm.

Through her epic cultural fails, viewers get a dose not only of the myriad ways in which American tourists offend Parisians, but also of every antiquated stereotype about the French that producer Darren Star (of “Sex and the City” fame) could dredge up: All the men cheat on their partners, the boss smokes in her office, and everyone gorges themselves on croissants and still manages to stay bone-thin.

The French can’t get enough of it.

“I’ve watched the entire series even if it’s not highbrow,” says Agathe, a Parisian who works at Universal Music next door to the restaurant where many of the “Emily in Paris” scenes are filmed. (Like others interviewed, Agathe asked to be identified by her first name only.) “It’s a guilty pleasure.”

Agathe is not alone. After five episodes of its latest season, “Emily in Paris” became the most-watched show in France. Even French President Emmanuel Macron is a fan, after his wife, Brigitte, made a cameo appearance in Episode 7.

But now, there’s a chance that Emily will say “arrivederci” to Paris, after her marketing firm decided at the end of the fourth season to open a branch in Rome. That has French fans of the love-to-hate series, and even Mr. Macron himself, up in arms.

“We will fight hard. And we will ask them to remain in Paris!” Mr. Macron told Variety magazine in a recent interview. “‘Emily in Paris’ in Rome doesn‘t make sense.”

Indeed, it is largely thanks to Americans’ deeply rooted vision of France that “Emily in Paris” has been such a success. Even if they fantasize about Italy – think Julia Roberts languishing over a plate of pasta in “Eat Pray Love” – they fantasize about France more. The country has been the world’s top tourist destination for three decades, and France’s capital is the key to its soft power.

“France’s cultural power is ingrained in the French from an early age,” says Fabrice Raffin, a socioanthropologist who studies culture at the University of Picardie. “Our gastronomy, luxury, fashion, and history are pillars of French identity. There’s definitely something elitist about it.”

So while the French may be screaming at their television screens as they watch Emily attend yet another glamorous cocktail party without ever stepping foot in a smelly metro car, they can’t help but admit to getting sucked into Emily’s idealistic view of the city.

“Paris is amazing, and the show highlights the best parts of it,” says Elsa, joining Agathe outside their office. “On Sundays, I like to go around the city, visit the Eiffel Tower, and be a tourist.”

Plus, many French viewers say that, even if the stereotypes about them in “Emily in Paris” seem to date back to the Middle Ages, they’re still hilariously true.

“It’s obviously an exaggeration, but yes, the French love to complain, and we pretend to be anti-American like [Emily’s boss], Sylvie,” says Anis, taking a (stereotypically French) cigarette break with co-workers Agathe and Elsa. “The stereotypes are funny.”

As much as Emily makes us cringe, from her outrageous, wannabe-chic outfits to her obsession with getting Instagram likes, here’s hoping she decides to stay in the land of cheese and subpar coffee (Emily’s French co-worker said it, not me). The mayor of Rome, Roberto Gualtieri, told Mr. Macron over the social platform X to “relax” and focus on “more pressing issues.” Even some Italians are not convinced by her potential move.

“No, no, it has to stay here,” says Matilde Mudadu, a tourist from the north of Italy, who came with her parents to take a photo in front of Emily’s famous door. “I love Rome, but ‘Emily in Paris’ was born here and it has to stay here.”

The French might be sad if Emily leaves, but Americans in Paris wouldn’t shed any tears; many of them have had enough of the Chicago native’s absent-minded cultural blunders.

“French people assume you came here for the fantasy or the croissants, and it’s refreshing to them when they hear otherwise,” says Emily Omier, an American tech consultant who moved to Paris in May 2023. “I don’t know if the jokes will stop if Emily leaves Paris. Now, every conversation is the same: ‘Oh, your name is Emily? Like “Emily in Paris”!’ I just say, ‘Yeah, it’s me.’”

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Trading up to higher skills

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

This fall, American four-year colleges saw a big drop in first-year enrollments – more than 5% from last year. While the causes are many, one could be that the academic track in higher education is simply no longer attractive to many 18-year-olds. A Harvard University study of teens and young adults, for example, found that 58% say they feel a lack of direction and little to no purpose.

Both of these trends, however, belie another one: Enrollment in postsecondary career and technical education – or CTE, once known as vocational education – continues to rise. More to the point, the nonprofit Advance CTE that helps define “cluster groupings” for these types of jobs just updated the arrangements to reflect changes in fields from digital technology to agriculture over the past two decades. One big difference in the new job definitions: They focus more on the purpose and impact of the different fields.

Today’s young workers “find meaning in making contributions that positively affect those around them – coworkers, customers, and society more broadly,” concluded a study this year by American Enterprise Institute.

Trading up to higher skills

This fall, American four-year colleges saw a big drop in first-year enrollments – more than 5% from last year, based on preliminary figures. While the causes are many, one could be that the academic track in higher education is simply no longer attractive to many 18-year-olds. A Harvard University study of teens and young adults, for example, found that 58% say they feel a lack of direction and little to no purpose.

Both of these trends, however, belie another one: Enrollment in postsecondary career and technical education – or CTE, once known as vocational education – continues to rise. More to the point, the nonprofit Advance CTE that helps define “cluster groupings” for these types of jobs just updated the arrangements to reflect changes in fields from digital technology to agriculture over the past two decades. One big difference in the new job definitions: They focus more on the purpose and impact of the different fields.

Today’s young workers “find meaning in making contributions that positively affect those around them – coworkers, customers, and society more broadly,” concluded a study this year by American Enterprise Institute.

More states, such as Texas, Georgia, and Maryland, have increased funding for CTE. Many companies are dropping a college degree requirement for some positions, such as work in semiconductors. The gist is that the trades, or building and creating, are both needed more and better appreciated.

A good example of this shift is Skylar Eastman, a young woman from the Columbus area in Ohio. She is about to graduate from high school with three welding certifications and a job lined up.

“My family’s always pushed trades onto all of us, because it’s something that is always going to be needed,” she tells the Monitor. In Ohio, she is a part of a growing number of students and families who view career and technical education as a ticket to upward economic mobility.

“When I first saw [welding], I was like, ‘That would be really fun to do,’” Skylar says. “I could see myself having a career out of it.”

For one assignment, shop workers in her class built metal chairs and barbecue smokers. Some of their craft is on display at her school and a source of pride for the students.

In the midst of ever-advancing technology, some young people are falling in love with making things with their hands. They are also discovering ways to earn a living, using social media to both market themselves and develop close connections with consumers.

Making things for others is an opportunity for empathy, wrote Glenn Adamson, author of books on the meaning of the craft industries. “Just as a skilled maker will anticipate a user’s needs, a really attentive user will be able to imagine the way something was made,” he wrote in a 2018 book, “Fewer Better Things.” An appreciation of the deep skills needed to change the material environment, he said, opens us up to “better understand our fellow humans.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

Elections – making a choice

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 4 Min. )

-

By Judith Hedrick

Where does power truly belong, during an election period and beyond?

Elections – making a choice

Elections are times of choice. Yes, whenever an election is held, we decide on different issues and between political parties and their candidates. But we also make a deeper choice about what we believe is the power which governs.

What is the ultimate power governing me, my family and friends, my country, and even the world? Is it human personalities or is it God? Is it mortal mind or the divine Mind? Where do I put my faith?

Any polarization or conflict that arises in elections is the result of the belief that power belongs to people, who have both good and evil qualities, instead of to God. We get riled up because we are convinced that there are candidates whose political positions and activities will harm us. If personalities are able to rule, we do have reason to fear.

The Bible points us in a different direction, though: “Power belongeth unto God” (Psalms 62:11). Accepting that God, good, is all-powerful and governing human existence frees us from fear and distress. The Bible also says, “I am the Lord, and there is none else” (Isaiah 45:6). This shows us that the enemy is not a person. It is the false belief that there is a power, mind, or presence other than God.

Ignorance and fear are overcome through Christ, the true idea of God. When Pilate asked Christ Jesus before his crucifixion, “Whence art thou?” he didn’t answer. So Pilate asked Jesus whether he knew that as Roman governor he had the power to kill or free him. Jesus answered, “Thou couldest have no power at all against me, except it were given thee from above” (John 19:11).

Jesus wasn’t afraid; he understood that power belonged to God and not to Pilate.

To Jesus, God wasn’t just a large power in a world full of smaller powers – God, Spirit, was All, the only power. Thus he knew there is no real evil power or mind which could prevent him from fulfilling God’s will and completing his mission. He would be victorious no matter how it looked at that point. And in the resurrection he was indeed victorious.

The First and Second Commandments (see Exodus 20:3, 4) can help us guard our thought against resigning ourselves to any claim of evil, the way Jesus guarded his thought. The First Commandment teaches us to have no other gods before God. We are to have or worship no other power, no other presence, no other might or mind. From this basis, we become confident that God is our King and Christ our Savior, and that nothing else – not even politicians or political parties – can save or destroy.

The Second Commandment brings out that what tempts us away from God are images, mortal beliefs, of material or personal good or of evil – all graven (carved) in thought, and all denying the supremacy of God. We’re not to make “any graven image,” the commandment says.

News reporting, social media, television, convey many images of material power or powerlessness. We make a graven image of what we read or hear when we simply take the false beliefs into our thought rather than letting Christ lift our thinking higher and refusing to honor any power but God, good. Conversely, as we love and worship God, we lose our fear of evil. When the fear is gone, we are able to make intelligent decisions during elections. We will select what represents the highest right under the circumstances.

If our candidate doesn’t win and another does, we have the opportunity to continue to make a wise choice. Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of this news organization, wrote, “Between the centripetal and centrifugal mental forces of material and spiritual gravitations, we go into or we go out of materialism or sin, and choose our course and its results. Which, then, shall be our choice, – the sinful, material, and perishable, or the spiritual, joy-giving, and eternal?” (“Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896,” p. 19). We can choose the spiritual and go forward as Jesus did with a full faith in God, who is ceaselessly working His purpose out.

As we choose to honor the supremacy of Spirit, it is natural to maintain our higher view of, and trust in, the reality and influence of God’s power, whoever wins high office. We can know that the guidance and direction of God, Love, who is perfect good, is present with those elected, as well as with all who are part of the national government, and we can pray for their receptivity to that wisdom and understanding. We can continue forward, choosing to know that “the kingdom is the Lord’s: and he is the governor among the nations” (Psalms 22:28).

Viewfinder

No smashing, just dashing

A look ahead

Thank you for coming along with us today. Please come back tomorrow for our look at how early impressionist painters sought a new way of looking at the world after the destruction of Paris in the 1870s. It’s a testament to the ways that transcendent art can grow out of great turmoil.