- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 9 Min. )

In Today’s Issue

- The economy has improved. Here’s why it’s still a top issue in crucial Pennsylvania.

- Today’s news briefs

- Moon base to deep space: How China seeks to surpass US

- The Trump-Harris worldview divide: Fly solo, or with allies?

- Trump or Harris? Wall Street watches and shrugs – so far

- Ahead of Tanzania’s election, Maasai fight to stay put

- Candy corn and leaf piles: Falling in love with fall, again

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

Facts and feelings

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

In his article on the swing state of Pennsylvania, Simon Montlake includes a link to this article in The Economist: “The American economy has left other rich countries in the dust.” Is that how things feel? Not for many. That’s Simon’s point.

His article underlines that people generally vote based on what they feel, not impartial facts. That’s natural. But it can also lead to warped or incomplete views of the economy, government, or one another. And it’s a reminder that a broader worldview can reveal that how we feel isn’t the only – or often the best – lens.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The economy has improved. Here’s why it’s still a top issue in crucial Pennsylvania.

Perceptions of the economy loom large as the Harris and Trump campaigns compete for every last vote. Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley is a window on Americans’ lingering anxiety around inflation, even as wages catch up.

As an independent voter living in a battleground state, Elizabeth Brown has mixed feelings about former President Donald Trump.

She’s not crazy about his proposed tariffs, or the tone of his rhetoric. But when he was in office, her salary as a sales manager stretched further – she paid less for her apartment in Bethlehem and could put more meat in her grocery cart. And she hasn’t been able to discern how Vice President Kamala Harris would be any different from President Joe Biden.

Under Mr. Trump, “the economy was good. We didn’t have this situation on the border,” Ms. Brown says. Next week, she’s leaning toward casting her vote for him.

Although the economy has improved since Ms. Harris became the Democratic nominee, many voters still are not feeling it. Nostalgia for the pre-pandemic Trump economy is palpable in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley.

“Northampton County is probably the best bellwether county in the state,” says Charlie Dent, who represented the Lehigh Valley in Congress from 2005 to 2018. “Whichever [presidential] candidate wins there I believe is going to win Pennsylvania – and the presidency.”

The economy has improved. Here’s why it’s still a top issue in crucial Pennsylvania.

As an independent voter living in a battleground state, Elizabeth Brown has mixed feelings about former President Donald Trump.

She’s not crazy about his proposed tariffs, or the tone of his rhetoric, she says. But when he was in office, her salary as a sales manager stretched further – she paid less for her apartment in Bethlehem and could put more meat in her grocery cart. And she hasn’t been able to discern how Vice President Kamala Harris would be any different from President Joe Biden.

Under Mr. Trump, “the economy was good. We didn’t have this situation on the border,” Ms. Brown says. Next week, she’s leaning toward casting her vote for him.

For much of the past year, Mr. Trump led Mr. Biden by wide margins on the question of which candidate voters trusted more to handle the economy. Since Ms. Harris became the Democratic nominee this summer, however, she has closed that gap in most national polls, as economic indicators have grown increasingly rosy.

Recent data has underscored the strength of the U.S. economic recovery: low unemployment, rising wages for most workers, and GDP growth that outpaces other major economies. Inflation, which peaked at 9.1% in 2022, has fallen to 2.4%, and interest rates have come down, making mortgages more affordable.

Yet many voters say they’re not feeling it – and polls show the economy remains a top concern in Pennsylvania and other battleground states. One reason is that economic growth hasn’t translated into easy living for many middle-class Americans, who blame politicians in Washington for the still-high cost of groceries, gas, and other necessities.

Nostalgia for the pre-pandemic Trump economy is palpable in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, a hub of manufacturing and logistics a few hours west of New York City and New Jersey. Despite the row of decommissioned blast furnaces looming over Bethlehem, where steelmaking once employed tens of thousands of workers, this is no hollowed-out Rust Belt community. Job growth in health care and education, and proximity to major cities, has attracted newcomers, boosted employment, and raised household incomes in the bi-county region.

Factories are hiring unskilled workers starting at $20 an hour, says Don Cunningham, president of the Lehigh Valley Economic Development Corp. and a former mayor of Bethlehem. And unlike in previous eras, other job opportunities abound. “My old man worked in the steel mills. For the dollar he made in the mills, he couldn’t go anywhere else even if he hated his job,” he says.

Still, frustration over the increased cost of living runs deep here, even as wages are rising. This is what voters usually mean when they say their top priority for picking a president is the economy, says Christopher Borick, a political science professor and director of the Institute of Public Opinion at Muhlenberg College in Allentown. “Inflation is the lens by which those evaluations are ultimately made,” he says.

Mr. Trump held a rally in Allentown on Tuesday, a sign of the region’s importance in the waning days of the campaign. When he asked the crowd if they were better off than they were four years ago, many yelled “No!”

This has created a quandary for Ms. Harris, who is campaigning as a next-generation changemaker, while serving as vice president at a time when a majority of voters say the country is on the wrong track. Should she try to take credit for an economic recovery that is the envy of other industrialized nations? Or disavow its uneven distribution among a disgruntled electorate?

She has promised to “turn the page,” while struggling to explain what exactly she would do, or would have done, differently from Mr. Biden.

“Harris has aligned herself with Biden,” says Ms. Brown, the independent voter. “We don’t know what she would do as president because she’s not explained it well.”

Swing region in a swing state

Northampton and Lehigh counties together make up the Lehigh Valley, named for the river that bisects the region. While Lehigh County (population: 378,000) is anchored by Allentown, the third-largest city in Pennsylvania, and is reliably Democratic, Northampton (population: 313,000) is a swing county that voted twice for Barack Obama, then for Mr. Trump in 2016, and for Mr. Biden in 2020. It has backed the winning candidate in all but three presidential elections over the past century.

Both parties have mounted expansive and expensive efforts to reach voters in Northampton’s midsize cities, suburban townships, and rural communities, which distill the demographics of a typical Northeastern U.S. state – increasingly diverse, plugged into global markets, economically unequal – into a single geographical area.

“Northampton County is probably the best bellwether county in the state,” says Charlie Dent, who represented the Lehigh Valley in Congress from 2005 to 2018. “Whichever [presidential] candidate wins there I believe is going to win Pennsylvania – and the presidency.”

Polls show the two presidential candidates are effectively tied in Pennsylvania, which has 19 electoral votes, the most of any swing state. Mr. Trump won the state in 2016 by fewer than 45,000 votes; Mr. Biden flipped it in 2020 by running up the tally in cities and suburbs.

Victory in Northampton may hinge on whether undecided voters see Ms. Harris as a safe choice to shepherd the economy, says Mr. Dent, a moderate Republican who broke with his party and endorsed Mr. Biden in 2020. “I suspect many are saying, ‘Hey, maybe I was doing a little better under Trump,’ but they don’t like Trump very much because they don’t like his behavior.”

Mr. Dent has already cast an early vote for Ms. Harris, joining a swell of former GOP officials in Pennsylvania and other states trying to defeat Mr. Trump. “She and I will not agree on every issue, but in her, we have a capable leader who will always put the interests of our country before her own, unlike her opponent who will always put his personal interests ahead of those of the United States,” he said in a statement.

In recent weeks, the Harris campaign has sharpened its focus on wooing disaffected Republicans and right-leaning independents in swing states. But it also needs to turn out irregular voters in cities like Bethlehem and Allentown by convincing them that inflation is in the rearview mirror and focusing on what a Harris presidency could achieve.

Benefits versus tax cuts

Ms. Harris has offered a raft of policy ideas on housing, taxation, and child care benefits. Mr. Trump has proposed tax cuts on tipped wages and Social Security benefits, while promising across-the-board tariffs on imported goods. He also favors reducing regulations and taxes on corporations, as he did in his first term when he signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017.

Economists have warned that Mr. Trump’s tariffs and other fiscal policies would create more inflation and bigger deficits than Ms. Harris’ plans.

Amid this debate over future tax-and-spending plans, Mr. Trump’s core argument is mostly backward-looking: The economy was better when he was in charge, he has said repeatedly during the campaign. “We had the greatest economy in the history of our country,” he told a Fox News town hall on Oct. 16. (In reality, economic growth was middling under his watch, while global inflation was low.)

At a diner in Allentown, Richard Kromer is collecting prizes for a Veterans of Foreign Wars raffle. An Army veteran, he later worked at a zinc processor in Tennessee, before retiring in 2021 and moving back to Pennsylvania to take care of his father. He likes Mr. Trump but has major misgivings about his policy on Ukraine, which Mr. Kromer wants the U.S. to support.

On the economy, though, he’s not conflicted. Mr. Trump “had a very strong economy until COVID hit,” he says, ticking off his disagreements with Ms. Harris. “All she has done is put up prices. She doesn’t understand how inflation works.”

Other voters are more approving of the administration’s economic stewardship and more wary of Mr. Trump’s self-justifications and threats to imprison his foes. “It’s all about him and what he wants,” says Roger Aris, a retired restaurant owner in Bethlehem. Ms. Harris has to be loyal to President Biden, he says, but once in office he believes she would put her own stamp on fiscal policy.

“Instead of giving tax breaks to millionaires or billionaires, she wants to help poorer people,” he says.

Mr. Aris, who is 74, was born in Haiti and worked for decades in New York City before moving to Bethlehem. He has four children and 11 grandchildren and great grandchildren. His children, however, don’t all share his enthusiasm for Ms. Harris. Jacqueline Aris, who lives in Bethlehem with her four children, says the economy was better under Mr. Trump. She’s not planning to vote at all this time. “Whichever party wins, we’re all screwed,” she says.

Her friend, Stacie Miller, who works in human resources, says she will vote for Ms. Harris because she wants a woman in the White House. But she’s also feeling economically pinched, unable to afford a bigger house for her family. “The bills keep coming, and I don’t want to pay them,” she says.

One Democrat’s appeal in a tight House race

“V is for voting, to make your voice heard,” says Susan Wild, holding a picture book up for 12 fidgeting preschoolers sitting on an alphabet-themed rug. She smiles at the group assembled inside a brightly lit classroom and turns the page to the next letter.

In 2018, Ms. Wild, a Democrat, was elected to Mr. Dent’s former House seat, and is now locked in a tight race, one of two in Pennsylvania that could help decide control of the U.S. House. She’s running against Ryan Mackenzie, a GOP state representative from the region who has run for Congress in two other cycles. (His campaign didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Today, Rep. Wild is touring a child care center in Easton that has branches across her district; her own children, now adults, attended one, she tells the staff. Last year, she sponsored the Child Care for Working Families Act, which would cap child care expenditures at 7% of a family’s income and make it free to low-income families. She says passing that bill, which has also been introduced in the Senate, would be her priority if reelected.

“What I’m hearing from people is that their child care expenses rank right up there with their rent or mortgage,” she says in an interview.

But she also highlights low gas prices and wages that are finally growing faster than inflation. She tells voters Mr. Biden’s policies are working and that control of the House would make it possible for Democrats to do even more.

Still, she concedes that the feel-good factor isn’t quite there yet. “When people find that they’re earning more, they want to feel it. They want to feel like they’ve got the ability to buy a luxury item or go on vacation. If it’s just assisting you in getting by, you don’t feel like you’re really making more,” she says.

For those who don’t own a home, the cost of rent is a constant gripe. But it predates the pandemic and has partly been driven by newcomers from nearby states seeking cheaper housing. What has changed in recent years, and is keeping demand high, is growth in local employment, says Mr. Cunningham.

Coattail effects?

Even if Mr. Trump flips Northampton County, ticket splitters may reelect Rep. Wild, who has outraised her opponent and blanketed local airwaves with attack ads. Pennsylvania also has a Senate seat in the balance, with Sen. Bob Casey, the Democratic incumbent, holding a narrow polling lead over David McCormick, the Republican nominee. Both campaigns have each spent more than $100 million to elect their candidate.

Glenn Geissinger, chair of the Republican Party in Northampton County, says he’s confident that downballot Republicans will get a boost from the coattails of the presidential nominee, unlike in 2016 when Mr. Trump won over irregular voters who didn’t necessarily vote the entire GOP ticket.

In 2016, “I think people were going in and saying, I’m going to vote for Donald Trump [only],” he says. “The average American who is voting for Donald Trump now says, I need control of the Senate, I need control of the House, so that the policies that he wants to pass can be instituted.”

At a car wash in Easton, Chris Ozoemena is waiting for his Hyundai sedan before driving back to his shift as a line manager at a medical manufacturing plant. His family of four is “getting by,” he says, though he’d like to see lower food prices. But he doesn’t put much stock in the promises of any of the presidential candidates.

He’s also sympathetic to Mr. Biden, calling him an honorable man who was unceremoniously pushed aside by his party. To Mr. Ozoemena, leadership sometimes means making incremental progress – and being humble enough to admit it. “You’re not going to make America perfect. Just do your bit for four or eight years,” he says.

Today’s news briefs

• Lebanese evacuation: For the first time in the Israel-Hezbollah war, the Israeli army has issued an evacuation warning for residents in the entire eastern Lebanese city of Baalbek.

• RFK Jr. on ballot: The United States Supreme Court denies a bid by former independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to be removed from the ballot in Wisconsin and Michigan for the Nov. 5 election.

• Virginia voter rolls: The U.S. Supreme Court is allowing Virginia to resume its purge of voter registrations that the state says is aimed at stopping people who aren’t U.S. citizens from voting.

• European migration policies: Greece is seeking stricter European Union migration policies as it braces for a potential surge in migrants and refugees due to ongoing conflicts in the Middle East.

• Japan same-sex marriage ruling: A second high court rules that the Japanese government’s policy against same-sex marriage is unconstitutional.

Moon base to deep space: How China seeks to surpass US

The United States still dominates in space, but China’s star is rising. As the country’s latest crewed launch highlights a rapidly advancing space program, some wonder, Could China surpass the U.S.?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

A rocket blasted into the night sky early Wednesday morning, shooting three young astronauts toward China’s space station – and propelling the country’s growing space ambitions.

China’s goal, revealed this month, is to become the world’s leader in key space fields by 2050. Its sweeping plan involves building a moon base, exploring deep space, and probing topics like the origins of the universe.

China began its space program later than the United States and Russia did, and had periods of rocky development. But today, the country is effectively catching up, with postponed projects now reaching fruition, experts say.

Some U.S. officials have cast Beijing as a competitive threat, warning that China could exclude other countries from important lunar terrain and resources.

Indeed, China is pushing ahead with plans to put an astronaut on the moon by 2030 – which would make it only the second country to do so – and officials predict some of the young astronauts aboard Wednesday’s space flight could work from a future lunar base.

“The last few years have gone really, really well for them,” says astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell. “All this stuff they have had waiting ... now they can actually do it.”

Moon base to deep space: How China seeks to surpass US

With a fiery blaze, a Chinese Long March 2 rocket blasted into a starry night sky from this remote corner of Inner Mongolia early Wednesday, shooting three Chinese astronauts toward China’s space station – and propelling the country’s growing space ambitions.

China’s goal, revealed in an official blueprint announced this month, is to become the world’s leader in key space fields by 2050. Its sweeping plan extends in scope from exploring the moon, Mars, and deep space, and probes topics like the origins of the universe, quantum mechanics, habitable planets, and extraterrestrial life.

“We are extremely confident,” says Li Yingliang, chief of general technology of the China Manned Space Agency, speaking with reporters at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in northwestern China on the eve of Wednesday’s launch, China’s 14th crewed launch and 33rd overall. “Every aspect of our [space] technology is getting more mature by the day.”

China began its crewed space program in the early 1990s, later than the United States and Russia did, and had periods of rocky development and long delays. But today, China’s advances are such that it is effectively catching up, with key postponed projects now reaching fruition, experts say. Officials predict some of the young astronauts aboard Wednesday’s space flight could work from a future Chinese base on the moon.

“The last few years have gone really, really well for them,” says Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge and expert on China’s space program. “All this stuff they have had waiting ... now they can actually do it.”

A cosmic competitor?

China has entered “the fast lane” of science innovation, Wang Chi, director of the National Space Science Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, told a Beijing press conference announcing the country’s space plan on Oct. 15. According to the blueprint, China will be able to make important breakthroughs in space science by 2027, “rank among the international forefront ... in 2035, and become a world space science power by 2050,” he said.

Indeed, as China makes rapid advances in space exploration, some top U.S. space officials have increasingly cast Beijing as a competitive threat. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has warned, for example, that China could dominate key terrain and resources on the moon and exclude other countries.

“There is definitely potential for tension there,” although it is not inevitable, says Dr. McDowell. “If one country has an extensive functioning base and the other doesn’t, then ... that country is likely to determine standards.”

Chinese officials downplay such competition. Mr. Nelson’s “worries are unnecessary,” says Mr. Li.

Still, whether in parallel or in competition, China is pushing ahead its near-term plans to put an astronaut on the moon by 2030, which would make it only the second country to do so after the U.S. China also plans to build a moon base in coming years – as does the U.S.

“We want to put a person on the moon as soon as possible,” says Zhang Wei, director of the Utilization Development Department of the Space Applications Technology and Engineering Center at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Lunar ambitions

China is already chalking up global firsts in its moon exploration program. In June, for example, a Chinese lunar lander named Chang’e 6 successfully collected rocks and soil from the moon’s far side – something no other country has done – and returned them to earth for study. In 2020, the Chang’e 5 spacecraft brought back lunar soil samples from the moon’s near side.

China recently revealed that it is manufacturing “moon bricks” that simulate soil collected from the moon’s surface and could be used as possible building blocks for a future lunar base. The crew of the just-launched Shenzhou-19 mission, which docked safely at China’s space station on Wednesday, will perform durability tests on some of those bricks.

Such steps are important, experts say, as both China and the U.S. work toward building moon bases in what is considered prime lunar territory such as the moon’s South Pole, where it is believed water is trapped in rocks. “What might matter is if China establishes a base on the south pole before the U.S. and claims the territory,” says Dr. McDowell.

China plans to launch two more Chang’e lunar lander missions to the moon’s south pole in 2026 and 2028 that will carry out resource surveys and create a scientific research station. It is also developing a lunar rover vehicle, and researching ways to safely lengthen its astronaut deployments beyond the current six months. In September, it unveiled the design for its first lunar spacesuit, a lightweight one.

Relay race

A critical element of China’s crewed space program, experts say, is the steady, cumulative experience of its multiple generations of astronauts – a strength in full display in the run-up to Wednesday’s launch.

In the chilly darkness Wednesday morning, a cheering crowd of hundreds of Chinese schoolchildren and other well-wishers crowded bleachers as the Shenzhou-19’s three-person crew strode out in spacesuits, waving, as a band played a patriotic Chinese song.

“We learn from the astronauts! We salute the astronauts!” read a huge red banner with yellow Chinese characters.

The crew is commanded by veteran astronaut Cai Xuzhe, who took part in an earlier space station mission in 2022. Accompanying him are two younger astronauts from what China calls its “90s” generation, former air force pilot Song Lingdong and senior flight engineer Wang Haozi, who is only the third woman to carry out a crewed space mission in China.

“Manned spaceflight is a relay race,” Commander Cai told a press conference on the eve of the launch. Generations of astronauts and thousands of aerospace workers are taking part toward a single goal, he says: “Glory for the country.”

Yet even as the space race intensifies, Chinese officials acknowledged their many hurdles ahead, and voiced hopes for more international cooperation.

While China’s lunar landing mission is going smoothly now, “We are soberly aware that the ... technology is complex ... and the challenges are huge,” says Lin Xiqiang, deputy director of the China Manned Space Agency. Ahead of the launch, he also praised NASA’s “high regard for the safety of its astronauts” and extended China’s “best wishes for the safe return” of two U.S. astronauts delayed at the International Space Station.

China and the United States “both want to further humanity through space exploration,” says Mr. Li, the chief of general technology, recalling past extensive dialogues between China’s agency and NASA. “We hope we can carry out more practical cooperation and exchanges with the U.S. and other countries.”

The Trump-Harris worldview divide: Fly solo, or with allies?

U.S. foreign policy may not be a top priority for American voters this year, but it is certainly a concern around the world, much of which is riveted by next week’s election. A key question: how the next U.S. president will treat allies and alliances.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

However little American voters prioritize foreign policy, surveys indicate they want the United States engaged with the world and favor seeing the U.S. play a leadership role.

Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump appear to offer distinct foreign policy visions. For many analysts, the biggest difference between them can be boiled down to two words: multilateral vs. unilateral. And how their policies might diverge is probably clearest in the case of Ukraine.

Calling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine a threat to European security and democracy, candidate Ms. Harris has echoed President Joe Biden’s vow of “support as long as it takes.” Mr. Trump, on the other hand, has insisted he could end the war in a day, based in part on his relationship with Russia’s president.

“I’m not sure that at the end of the day there’s all that much difference between Harris and Trump on some of the big foreign policy issues, but where there is lots of daylight is on Russia and Ukraine,” says Michael Desch at Notre Dame.

“Harris would continue with the establishment consensus on supporting” Ukraine, he says. “But Trump is a different story. He’s not committed to helping Ukraine ... and he thinks he can do business with Vladimir Putin.”

The Trump-Harris worldview divide: Fly solo, or with allies?

In most polls asking voters to list the issues that will influence their choice in next week’s presidential election, foreign policy fares little better than an also-ran.

The economy, immigration, reproductive rights, and threats to democracy come out on top.

Yet at the same time, some surveys, such as the Chicago Council on Global Affairs’ annual gauge of public opinion and foreign policy, show that Americans still want to see the United States play a leadership role in international affairs.

Moreover, some voters suggest that a candidate’s worldview and actions on the world stage provide evidence of his or her character and leadership style, and whether that fits with their own vision of how American leadership should be exercised.

Viewed through that prism, Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump appear to offer distinct foreign policy visions that spring from very different worldviews.

In the case of Vice President Harris, a range of foreign policy experts use these words or phrases to describe her worldview: multilateral, cooperation, security through alliances, continuity, or Biden-lite. But words like “nebulous” and “undefined” also pop up.

For former President Trump, the words and phrases these experts say capture his worldview are based on his term in office: unilateral, “America First,” transactional. But “chaotic” and “unpredictable” – even “volatile” and “dangerous” – make a showing.

For many analysts, the biggest difference between the two presidential candidates when it comes to U.S. relations with the world can be boiled down to two words: multilateral and unilateral.

Does America really need its friends?

More broadly, Vice President Harris is seen as a champion of America’s traditional post-World War II role, leading alliances of like-minded democracies – think NATO, the Organization of American States, and the more recent Asia-Pacific Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or Quad, grouping – and promoting the postwar liberal world order.

President Trump, on the other hand, established a record of disdain for America’s alliances. He is seen as more comfortable with the idea of the U.S. defending its own interests in an era of rising big-power competition.

“We don’t know for sure, but my guess is that Harris is likelier to be open to investing American assets and treasure if you can get allies and international institutions to go along,” says Kori Schake, director of foreign and defense policy studies at the conservative American Enterprise Institute (AEI) in Washington.

“Trump is more likely to be comfortable with unilateral action,” she adds, “while Harris would be unwilling to take a position that no one else would align with.”

Beneath the unilateral vs. multilateral question lie differing views of the costs and benefits of maintaining Washington’s global leadership role.

“Americans got used to hearing that our military actions in Somalia or Iraq or Libya were part of our global leadership,” says Paul Saunders, president of the Center for the National Interest in Washington. But Mr. Trump has tapped into a growing sense among Americans that the costs of that leadership are increasingly outweighing the benefits, he suggests.

Weighing the costs and benefits of U.S. leadership

Vice President Harris would adhere to a more conventional foreign policy and leadership style, consulting both her aides and foreign allies, says Mr. Saunders. Mr. Trump, he predicts, would rely more on his own instincts, and his ambition to “close the deal,” even though “his record is very mixed when it comes to foreign policy.”

His quick report card for President Trump: success in clinching the Abraham Accords that normalized relations between Israel and a number of Arab countries, and success with a modest rewrite and update of the North American trade deal, then called NAFTA.

“But there was no ‘big deal’ with Russia, or North Korea, or Iran,” Mr. Saunders adds, “nor was there any deal with Beijing that the Chinese stuck to.”

As a vice president, Ms. Harris has not been free to hew her own foreign policy path. She would be most likely to differentiate herself from President Biden in relations with Israel, showing a willingness to stand up sooner and more publicly to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, some experts say.

The clearest differences between the two presidential candidates, though, are likely to emerge over Ukraine. Candidate Ms. Harris has framed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the same terms as the Biden administration, calling it a violation of international law and a threat to European security and democracy. She has echoed President Biden’s vow of “support as long as it takes.”

Mr. Trump, on the other hand, has insisted he could end the war in a day, drawing in part on his relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

While the former president has offered no details of how he would conclude a peace accord, some former aides say his deal would mean significant territorial concessions by Ukraine – with little concern for how such a solution would go over with European allies.

“Harris would continue with the establishment consensus on supporting [Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskyy and the Ukrainians,” says Michael Desch, director of the Notre Dame International Security Center in Indiana.

“But Trump is a different story. He’s not committed to helping Ukraine, we already know he’s a NATO skeptic,” he adds, “and he thinks he can do business with Vladimir Putin.”

Is Trump better in tune with today’s world?

There are good reasons to doubt the likelihood of a magic formula quickly ending Russia’s war in Ukraine, Dr. Desch says. But at the same time he suggests that much about Mr. Trump’s approach to foreign policy may fit better than Ms. Harris’ approach with today’s world.

“So much of the establishment fixation with American leadership is nostalgia for the unipolar moment that is past,” he says. On the other hand, he sees Mr. Trump as more comfortable with a world that is “more like late 19th century Europe.”

“America is still a great power,” he adds, “but there are other great powers out there, including China and Russia, that have to be taken account of.”

Ms. Schake, the AEI’s foreign policy expert, says no one should doubt that the United States needs a strong leader to pursue core national interests in a world that remains highly interdependent. But she is concerned by the authoritarian tone of some of Mr. Trump’s remarks.

“So many of my fellow Republicans who are reluctantly aligning with Trump acknowledge that things he is saying are terrible,” she says. “But they say, ‘Look at what he does, don’t listen to what he says.’”

In response, she says she tells them, “You would always say that we should take Putin and [Chinese leader] Xi Jinping at their word. So how is it wise to ignore the words of Donald Trump?”

Trump or Harris? Wall Street watches and shrugs – so far

Amid all the turbulence surrounding the Harris-Trump presidential race, Wall Street isn’t panicking. The stock market is up, in part because politics don’t drive the whole economy. Still, the Trump tariff proposals draw warnings.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

Amid the alarm bells and hand-wringing over this year’s presidential election, there’s one prominent island of calm: Wall Street.

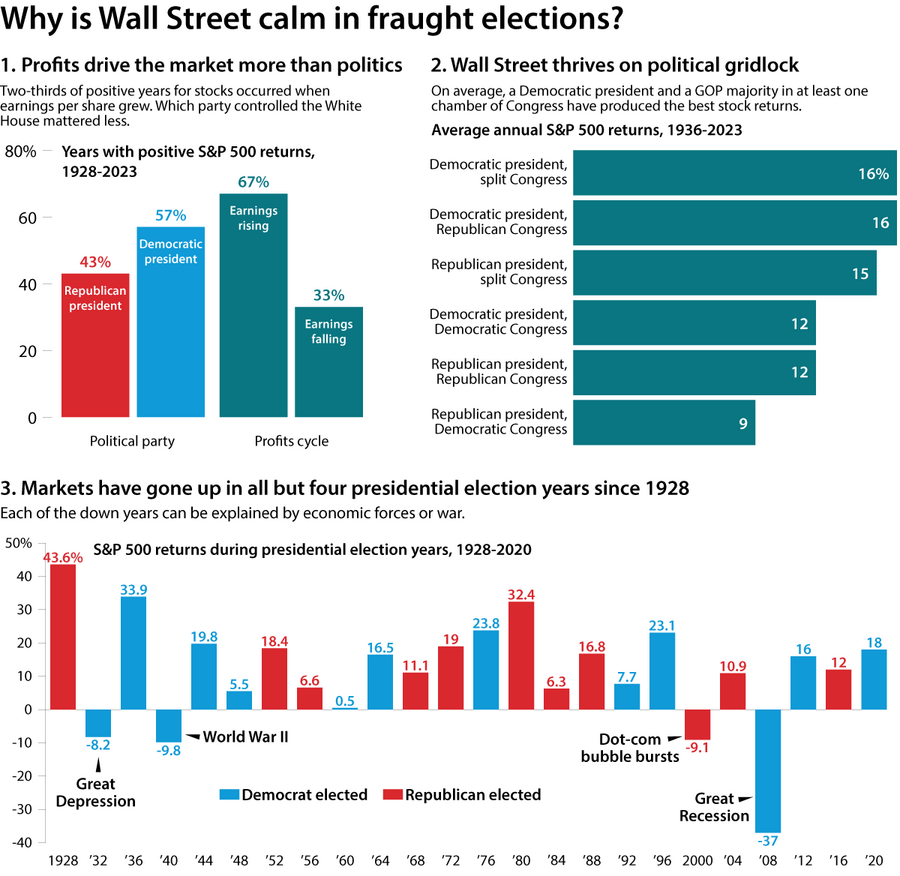

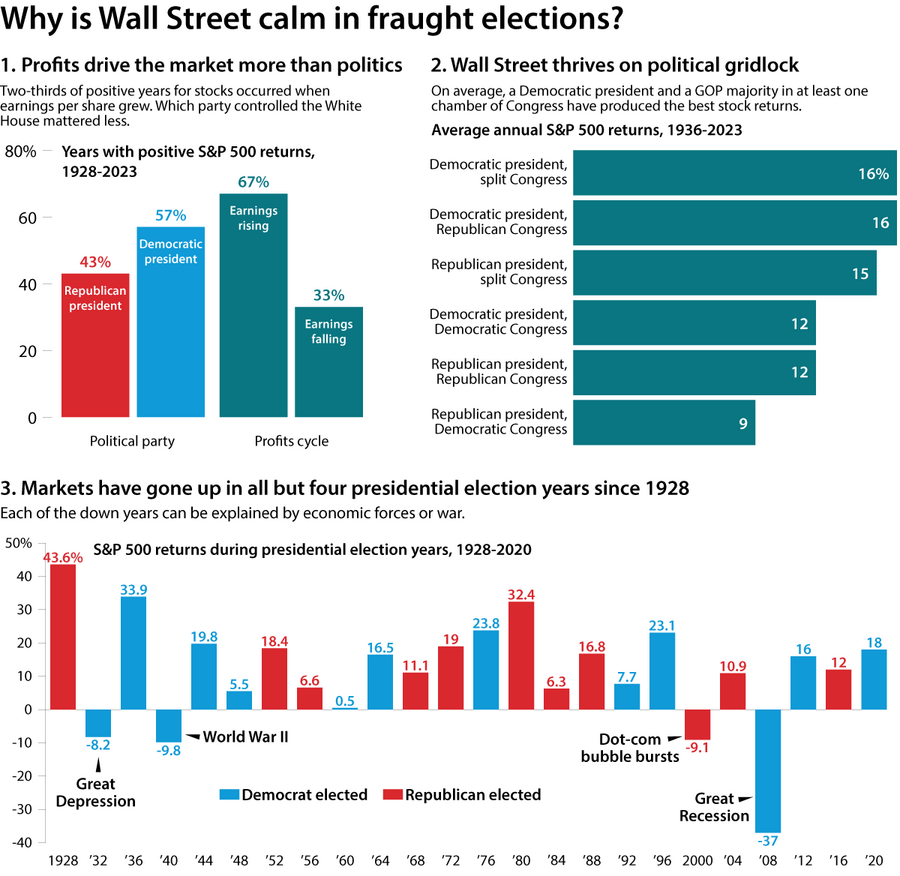

The stock market has remained buoyant even in a race between two starkly different candidates and with no clear sense of which one will win. Sure, Vice President Kamala Harris might raise taxes and former President Donald Trump could widen the deficit. But history suggests that elections don’t matter all that much to the stock market, especially if they result in split party control of Congress and the White House.

With Election Day less than a week away, the S&P 500 is up by double digits for the year.

There’s one fly in this ointment of market serenity: Mr. Trump’s proposed tariff hikes. They threaten to raise prices for consumers, stoke inflation, and slow growth.

The issue is not so much that Wall Street doesn’t perceive the threat. What’s hard to pin down is how far tariffs might reach and how much damage they might do. In a worst-case scenario tariffs can spark a tit-for-tat trade war – something that history suggests would end badly for everyone.

Trump or Harris? Wall Street watches and shrugs – so far

Amid the alarm bells and hand-wringing over this year’s presidential election, there’s one prominent island of calm: Wall Street.

The stock market has remained buoyant even in a race between two starkly different candidates and with no clear sense of which one will win. And a good many are predicting stocks will be higher still at year-end. Sure, Vice President Kamala Harris might raise taxes and former President Donald Trump could widen the deficit. But history suggests that elections don’t matter all that much to the stock market, especially if they result in split party control of Congress and the White House.

With Election Day less than a week away, the S&P 500 is up by double digits for the year.

There’s one fly in this ointment of market serenity: Mr. Trump’s tariff proposals. A radical departure from decades of bipartisan American policy, they threaten to raise prices for consumers, stoke inflation, and slow growth. Both sides of the political divide warn that tariffs could even spark a trade war with dire and unpredictable effects.

“This is a prescription for the mother of all stagflations,” Larry Summers, Treasury secretary during the Clinton administration, told Bloomberg TV back in June.

Mr. Trump’s “tariff agenda is an anti-growth wild card that poses considerable economic risk in a second term,” The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board intoned two weeks ago.

The issue is not so much that Wall Street doesn’t perceive the threat. Very few analysts believe Mr. Trump’s rhetoric that tariffs would boost growth. What’s hard to pin down is how far tariffs might reach and how much damage they might do.

Is he serious about imposing tariffs, even on the imports of U.S. allies? What happens if they retaliate? Would Mr. Trump raise trade duties even more, sparking a tit-for-tat trade war that, history suggests, would end badly for everyone?

“No one wins trade wars,” says Warren Maruyama, a senior counsel at Hogan Lovells and former general counsel of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative under President George W. Bush. “They tend to be very, very ugly. And people get hurt.”

Stocks have risen in most presidential election years

Some sectors of Wall Street have concerns, especially bond traders, who worry the higher inflation expected under Mr. Trump would force hikes in interest rates. Rate rises would lower bond values. But optimism still reigns generally, because of other considerations. One is the hope that other bits of Mr. Trump’s agenda, particularly deregulation and lower taxes, would offset any negative consequences from tariffs.

Another is market history. Stocks have risen in all but four presidential election years since 1928, points out First Trust Portfolios. And in those four elections – 1932 (the Great Depression), 1940 (World War II), 2000 (the bursting of the dot-com bubble), and 2008 (the global financial crisis) – economics and war weighed much more on investor sentiment than the candidates’ economic policies.

Bank of America, First Trust Portfolios, Morningstar, Ibbotson Associates

“U.S. corporations are global, U.S. policy is just a subset of what impacts corporate America ... and even major policy changes like corporate tax rates and tariffs tend to be competed away over time,” concluded Bank of America Securities in a July analysis of election effects on markets. This year, corporate earnings look to accelerate and Wall Street, with its typical stock-specific focus, has pushed markets to new records in recent months.

Others hope that Mr. Trump would move slowly to implement his trade policy – or that Congress or the courts would block such moves. But one trading firm reports that Robert Lighthizer, Mr. Trump’s U.S. trade representative and close adviser on trade, is telling money managers that a second Trump administration would move quickly to implement his sweeping tariff plans. As for Congress or the courts stepping in, the former has over the years given presidents broad authority to act unilaterally in emergency situations, and the latter has given presidents wide latitude in foreign affairs.

“The courts have tended to give the president a fair amount of running room when it comes to actions that involve national security, international economics, or international trade policy,” says Mr. Maruyama, the former general counsel of the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative.

Would tariffs spark a deal, or a trade war?

Another hope is that Mr. Trump’s professed love of tariffs – “the world’s most beautiful word,” he said in Chicago two weeks ago – is merely a negotiating tactic. Supporters point out that he instituted tariffs on steel and aluminum in 2018 and threatened duties on car imports in order to wring concessions from Canada and Mexico in successfully negotiating the USMCA trade pact. He now may be doing the same with Europe in part to create a united front against Russian aggression and Chinese imports, writes Nadia Schadlow, senior fellow at the conservative Hudson Institute and deputy national security adviser for strategy in the Trump administration.

If Europe can stop viewing him as an enemy, she says, “A pro-growth, pro-freedom partnership is possible.”

But that will be hard to do when Mr. Trump is threatening across-the-board 10% to 20% tariffs on all imports, including those from Europe. The more likely scenario is that other nations would institute tariffs of their own against U.S. imports.

“If he gets exactly what he says he wants, you’re going to see retaliation,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics.

How bad it gets depends on how far the retaliation goes. The Tax Foundation estimates the net effect of Mr. Trump’s tariffs would drag down the long-term growth of U.S. gross domestic product by 1.3% and create 1 million fewer jobs than the status quo. If foreign nations retaliated, GDP would slow another 0.4% with an additional 362,000 jobs not created. If the former president upped the ante with more across-the-board tariffs, it’s difficult to model how much more damage there would be.

This uncertainty poses possibly the biggest problem. It causes consumers to rein in spending and businesses to cut back investments, slowing growth.

“Any short-term benefits gained by driving a hard bargain in bilateral negotiations or in a given industry would be vastly outweighed by the macroeconomic costs of generating uncertainty,” writes Adam Posen, president of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, in Foreign Affairs magazine. “This is the fundamental flaw that shapes Trump’s agenda.”

Bank of America, First Trust Portfolios, Morningstar, Ibbotson Associates

Ahead of Tanzania’s election, Maasai fight to stay put

For years, Tanzania’s government has been trying to push Maasai pastoralists off their ancestral land to make way for conservation projects. But the community is fighting to stay put.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Kizito Makoye Contributor

In August, more than 40,000 people in Tanzania discovered an alarming change to their voter registration.

In the past, members of the Maasai community have always cast their ballots in their hometowns in the country’s north. For the local election in November, however, they had been assigned to a polling station hundreds of miles away.

The decision sounded alarm bells among many Maasai, pastoralists who have repeatedly clashed with the Tanzanian government in recent years over their right to stay on their ancestral land in the Serengeti.

Since 2022, the Tanzanian government has relocated more than 9,600 Maasai from this corner of the country, often through forced evictions. It claims the Maasai’s presence threatened the conservation of the Serengeti’s world-famous, acacia-dotted landscapes. But watching that same land being carved up for safari parks and trophy-hunting reserves, Maasai and their supporters suspected less pure motives.

For many, the voter registration change was the final straw.

“It feels like they’re pushing us out,” explains Daudi Saning’o, a Maasai herder.

Soon, he joined thousands who poured into the streets, blocking safari vehicles and wielding signs that read, “We will fight for our land until the end.”

Ahead of Tanzania’s election, Maasai fight to stay put

On a chilly morning in mid-August, Daudi Saning’o set off as usual from his home on Tanzania’s Serengeti plain, his horned cattle lazily roaming alongside him. Their bells clanged softly. For as long as he could remember, tending to his herd here had been his life’s purpose, and a connection to his pastoral Maasai heritage.

“I love my livestock as much as I love my family,” says the 40-something father of seven.

Now, however, Mr. Saning’o’s way of life was under siege. Since 2022, the Tanzanian government had relocated more than 9,600 Maasai from this corner of the country. It claimed their presence threatened the conservation of the area’s world-famous, acacia-dotted landscapes. But watching that same land being carved up for safari parks and trophy-hunting reserves, Maasai and their supporters suspected less pure motives.

And the pressure was still building. That morning, as Mr. Saning’o walked beside his cows, he got a call from a friend. The man told him to check his voter registration.

When he did, Mr. Saning’o discovered that for the local government elections on Nov. 27, he had not been assigned to vote in his own village, as he always had in the past. Instead, he had to cast his ballot in the town of Msomera, a seven-hour bus ride away.

Although Mr. Saning’o had never been there, the name was familiar. It was the location of the settlement the government had built for Maasai whom it had moved out of the Serengeti. Looking at his registration, Mr. Saning’o feared he would be next.

“First, they banned us from grazing [in certain areas]. Now they don’t even want us to vote in our own villages,” he says. “It feels like they’re pushing us out.”

Pristine landscapes

Around the time Mr. Saning’o learned about his new polling station, more than 40,000 other Maasai made the same discovery. Their registration had been moved to Msomera, only three months ahead of voting day on Nov. 27, according to Giveness Aswile, a spokesperson for the Independent National Electoral Commission.

The decision sounded alarm bells among many Maasai, who saw it as a tactic to further weaken their formal connection to their land.

Historically, the Maasai have herded their cattle on the plains that straddle northern Tanzania and southern Kenya. Today, most Maasai in Tanzania live in a district called Ngorongoro.

But they are far from the only ones with an interest in that land. The site of one of the largest animal migrations on Earth and unique geological features like the world’s largest volcanic caldera, Ngorongoro has long been a magnet for all kinds of global do-gooders and adventure-seekers – and their money. Today, its game reserves draw about 750,000 tourists a year.

The region is a particularly beloved holiday destination of the Dubai royal family, who come by private jet to shoot lions and other wildlife in their own private game reserve. One sheikh recently signed a deal to lease a vast swatch of Tanzania’s forests – totaling 8% of the country’s land – for a carbon offset business.

Part of the region’s allure is its supposed emptiness – a place that appears untouched by humans. Tanzania’s government says the growing Maasai communities in the region threaten both the wildlife and natural environment.

Since 2022, it has used a variety of tactics to compel Maasai to leave Ngorongoro. On protected land, their cattle-grazing has been severely restricted and key water supplies cut off. Social services such as hospitals and schools have been shuttered. Some Maasai communities have been evicted by force, while others have taken buyouts to move out of the region.

To date, about 10,000 Maasai have moved to Msomera, a town more than 300 miles away in a dry, windswept part of eastern Tanzania. There, large polygamous families are crowded into single houses, and people say the parched land is not suitable for grazing their herds.

“It’s very difficult, we are losing our way of life,” says Edwin Nang’oye, a father of eight from two wives. He moved to Msomera in March after accepting a government offer of 10 million Tanzanian shillings (about $3,600) and a small house.

Dignity at stake

In mid-August, Mr. Saning’o joined a large group of Maasai in staging protest marches calling for their voter registration to be changed back to Ngorongoro. One human rights activist estimated that thousands of people joined the demonstrations.

“If the relocation exercise is voluntary, why have they removed villages” from the list of local wards, asked James Moringe, a councilor for Alaitole ward in Ngorongoro.

Demonstrators marched with banners carrying messages like “We will fight for our land until the end,” singing and tearfully reciting prayers as they went. They blocked roads, cutting off access to the Toyota Land Cruisers that carried binocular-wielding safari tourists into the conservation area each day.

“When our right to vote is taken away, our dignity, too, is at stake,” explains Rose Njilo, a local leader who was part of the protests.

At first, the government denied there was any problem with the voter roll. But after five days of protest, and an emergency court order to reinstate the Ngorongoro wards removed from the voter roll, a representative of the president arrived to address the demonstrators.

“All eligible citizens in Ngorongoro will be allowed to vote in their respective areas, just like any other Tanzanians,” explained William Lukuvi, a cabinet minister, according to local television reports.

Supposedly, it was a victory. But Mr. Saning’o and other demonstrators cannot shake the feeling that the fight isn’t over.

Many Maasai say that after the problems they faced, they could no longer vote for the ruling Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party. “How can I support a party that doesn’t respect our rights?” asks Mr. Saning’o, who was previously a loyal CCM supporter. Supporting the opposition, however, is no simple choice in Tanzania, where non-CCM candidates and supporters are frequently harassed and intimidated. During the last local government elections in 2019, the opposition chose to boycott the vote altogether in protest against CCM manipulation of the polls.

For the Maasai, the goal of the election is simple: to choose representatives who support their right to be in Ngorongoro.

“This land is everything to us,” Mr. Saning’o says. “And we will fight to stay.”

Essay

Candy corn and leaf piles: Falling in love with fall, again

The riot of russet tones, the brisk air, the glow in the sky. A veteran writer of The Home Forum sings the praises of fall, and reminds us that the answer to what ails us is often as simple as stepping outside and breathing in nature’s glory.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Murr Brewster Contributor

It was always the grown-ups who loved autumn. It was hard for us kids to work up any affection for the season that buried summer vacation, but the old folks would ramble on, in their old-folks way, about the glories of fall: the light, the colors, brisk air, sweaters, and, inexplicably, squash.

The old folks were rapturous, but we had to go back to school. It was many years before I realized that the fact that we had to go back to school was another plus in the autumn column for the adults.

Now I’m in my own autumn, and it’s fall again, and a swirl of yellow leaves rides a breeze to the ground.

Around every tree is its own reflection, orange and red and yellow rings pooling out in ripples. A loamy fragrance calls up my childhood. The senses gather up the scene, and the heart runs right at it and leaps in. It is the very antidote to agitation.

Candy corn and leaf piles: Falling in love with fall, again

It was always the grown-ups who loved autumn. It was hard for us kids to work up any affection for the season that buried summer vacation, but the old folks would ramble on, in their old-folks way, about the glories of fall: the light, the colors, brisk air, sweaters, and, inexplicably, squash. The old folks were rapturous, but we had to go back to school. It was many years before I realized that the fact that we had to go back to school was another plus in the autumn column for the adults.

There were a few grumps who saw nothing to like about fall, and plenty to rake, but it would be another 20 years before they would be relieved of their suffering by the gas-powered leaf blower. And then they could ruin autumn for everyone else.

Used to be, though, we had fun with that chore. The neighbor girl and I raked leaves into blueprints of dream houses and gave each other tours, carefully using the door holes, proudly pointing out our favorite rooms. Eventually we razed the development and raked the partitions into gigantic piles for jumping in. Even the timid could manage a cannonball into these buoyant heaps, rewarded by a moment of flight and a soft landing, and we lingered in the good loamy aroma, snug as nestlings. We picked the bits from our sweaters, re-raked, and did it again and again. And did it once more in our teens, in a fit of what passes for nostalgia in the still young. (We discovered gravity had a much stronger opinion about us then.)

Daddy was an Adlai Stevenson man and had the only compost pile on the block, but the neighbor, who liked Ike, could always be counted on to burn his leaves. The smell was heaven. You can’t burn your leaves now, and it’s probably just as well, but if I squeeze my eyes halfway shut and unfocus my brain, I can still pull up the distinctive aroma of leaf smoke.

And snagged along with that recollection come other things: candy corn, and bright turkeys made with construction paper, little rounded scissors, and paste from a jar with a spatula hanging from the lid. The turkeys started as a tracing of one’s hand. It felt really good to have someone trace your hand, sliding the pencil between your fingers; better than you might think. The rounded scissors were not designed for cutting, though you could run with them all you wanted. Still, we got our turkeys cut out, selecting from a stack of colored paper that looked like wealth itself. The paste, which was rumored to be tasty, tended to harbor dried-up bits, which made our turkeys lumpy.

We weren’t too young for homework. Our assignment was collecting fall leaves. They were a whole new currency to add to the construction paper, with maples having the highest denomination. That week in school we would go through lots of paste, and flick speckles of paint on our leaves using an old toothbrush. A smile from Mommy and a stint on the refrigerator were all the praise we needed.

Now I’m in my own autumn, and it’s fall again, and a swirl of yellow leaves rides a breeze to the ground. Around every tree is its own reflection, orange and red and yellow rings pooling out in ripples. A loamy fragrance calls up my childhood. The senses gather up the scene, and the heart runs right at it and leaps in. It is the very antidote to agitation.

Soon enough, I suspect, this landscape will be spanked to perfection, and disappoint the eye. My town is late to the noble duty of infringing on the citizens’ freedom to own leaf blowers, but a ban is finally being phased in, and in a couple of years we might regain a freedom young people have never known.

But look! There’s a little colonnade down by the river. Two columns of trees regard each other across a broad walkway and release their leaves. Distant geese hootle high above the fog. Water slaps at the seawall. It may be a triumph of artistic sensibility, or it may be a shortage of tax revenue, but the leaves have been left unmolested. They are an impossible pink: plumes of pink in the crowns of the trees, puddles of pink spreading out beneath, and in between, I swear it, pink air.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Creativity as a small nation’s defense

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

One trend of recent decades has been that of small countries trying to prevent a foreign invasion by making themselves indispensable to big countries around them. A would-be invader might think twice before destroying what it is dependent on. The secret of this strategy? Build up trust in your economy and bring out the creativity of your people. Rely on qualities more than on armaments.

Armenia, population under 3 million, is racing to go down the path of becoming the next Silicon Valley – especially after seeing Russia invade Ukraine. About the size of Maryland, it faces a foe different from Russia. Last year, neighboring Azerbaijan (population 10 million) invaded a disputed region called Nagorno-Karabakh, forcing more than 100,000 ethnic Armenians to flee the enclave.

Both countries are currently negotiating a peace deal, but Azerbaijan still has eyes on a vital transit route in Armenia.

“For Armenia, a country that faces complex geopolitical challenges, leveraging science and technology is not only about economic growth but also national security, resilience, and sustainability,” says Alen Simonyan, speaker of Parliament.

Creativity as a small nation’s defense

One trend of recent decades has been that of small countries trying to prevent a foreign invasion by making themselves indispensable to big countries around them. Singapore, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates, for example, have become global tech hubs or finance centers. A would-be invader might think twice before destroying what it is dependent on.

The secret of this strategy? Build up trust in your economy and bring out the creativity of your people. Rely on qualities more than on armaments.

Now Armenia, population under 3 million, is racing to go down the path of becoming the next Silicon Valley – especially after seeing Russia invade Ukraine. In fact, the former Soviet state got a big head start in 2022 when thousands of Russian techies fled their country after the invasion and chose Armenia, a democracy, because of its ecosystem of hundreds of dynamic tech startups.

About the size of Maryland, Armenia faces a foe different from Russia, with which it has recently had mixed relations. Last year, neighboring Azerbaijan (population 10 million) invaded a disputed region called Nagorno-Karabakh, forcing more than 100,000 ethnic Armenians to flee the enclave.

Both countries are currently negotiating a peace deal, but Azerbaijan still has eyes on a vital transit route in Armenia called the Zangezur Corridor. Iran and Turkey, which border Armenia, have strong opinions on that hot territorial dispute.

“For Armenia, a country that faces complex geopolitical challenges, leveraging science and technology is not only about economic growth but also national security, resilience, and sustainability,” Alen Simonyan, speaker of Parliament, said at a conference in October.

Last year, Armenia doubled the number of tech workers from the year before. Several American tech giants have opened offices or research centers in the country. In early October, the country hosted the World Congress on Innovation and Technology.

“Armenia’s survival, which now faces existential threats, is of great importance,” Valery Safarian, head of the Belgian-Armenian Chamber of Commerce, told Armenpress Armenian News Agency. “It’s important to underscore that Armenia has strategic assets, particularly in the sector of semiconductors and electronic chips.”

But it is the country’s fearless drive to innovate that may be its first defense. “When creating startups people think ‘what if we aren’t good enough’?” Tigran Petrosyan, a co-founder of the Startup Armenia Foundation, told Armenpress last year. “I’d advise everyone to make the steps forward and understand the reality while doing so. There’s only one way here, keep moving forward regardless of anything.”

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

It has to be Love

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 2 Min. )

-

By Kit Cornell Kurtz

Beyond partisan divides, God’s law of love is always active, uplifting all with grace, peace, and harmony, as this poem conveys.

It has to be Love

If we look

and think we see

chaos’s fragments or hate’s clutter

swirling like a sandstorm – blinding –

we can remember God, Love, is sovereign;

Her law’s supreme.

All are sheltered snugly

under Her wing.

Gracious God,

our loving Father-Mother,

holds one and all

safely, securely, happily

in Her kingdom –

the present, palpable, peaceful place

of Her embrace.

Clashing opinions, wayward words,

promises lightly given,

or threats of dire destruction

cannot touch God’s design.

Love and harmony are here for

each and every individual.

We are Her creation.

Even when human patterns

settle into votes

submitted, tallied, ratified –

some candidates in,

some candidates out –

God’s government is

always in place,

moving forward

with Love’s grace.

God’s law is supreme,

the rule of the good and true.

We do not need to wait for

the dust to settle

to see it,

for even blinded eyes

– ours or others’ –

have the capacity to

see Love’s hand

helping, guiding, lifting

and aligning thought

with gentle, universal Love.

Even hardened hearts

– theirs or ours –

can find that Love

cannot be refused.

All can feel Her ever-presence

encircling us –

can feel goodness, kindness, mercy, grace.

Father-Mother God’s

gentle lovingkindness

knows no partisan walls,

no warring bands,

no hate,

no deadening disappointment.

To Love divine, all is love.

She sees only Her children

as she made them –

not volatile mortals but

wholly spiritual,

good at heart,

pure in spirit,

wise –

each expressing

divine Mind’s abilities

and intelligence.

Love heals

blinded eyes,

hardened hearts,

with Christly touch.

And what we see,

to act upon,

it has to be love,

fully love,

in line with

the law of Love.

We are held in Love,

for Love divine

is All –

sovereign,

supreme,

and infinitely kind.

Viewfinder

Big aspirations

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us. Please come back tomorrow when correspondent Fred Weir looks at how Vladimir Putin has been able to remain in power in Russia for 25 years – with few signs of his leadership ending anytime soon.