- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usIn Today’s Issue

- For Syrians, Assad is in the past: ‘The thing we all have now is hope’

- Today’s news briefs

- What next for leaderless Syria, once the Mideast’s hub?

- How birthright citizenship could change under Trump

- South Koreans say fight for democracy is not over

- How a revered starchy side dish helped choose Ghana’s next president

- This Delhi cop wants to ‘spread goodness.’ He set up a school.

Monitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A historic moment in the Middle East

Mark Sappenfield

Mark Sappenfield

What just happened in Syria? In his Patterns column today, Ned Temko calls this a “fall of the Berlin Wall” moment for the Middle East. The challenges will be enormous, and Ned lays them out carefully. But stunningly, a ruthless dictator is gone as crowds chanted, “One, one, the Syrian people are one!”

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

For Syrians, Assad is in the past: ‘The thing we all have now is hope’

After decades of repression, the pace of political change in Syria over the weekend was stunning. But resetting the country’s institutions and reassuring the public will be painstakingly slow.

Syrians at home and abroad were still reeling Monday that what long seemed impossible – the overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime – took place in just a matter of hours this weekend.

After years of sectarian massacres, intercommunal conflicts, and jihadist violence, Syrian opposition forces that swept into Damascus early Sunday and chased Mr. Assad into exile in Russia are now in control of much of the still-fragmented country.

It’s an inflection point after 53 years of ruthless, repressive Assad family rule. Syrians who exchanged greetings and congratulations as strategic cities fell to the rebels quickly started dreaming of returning to their homes and reuniting with loved ones.

“I am sleepless and so happy,” says longtime Syrian dissident and former political prisoner Anwar al-Bunni in Berlin. “The goal that Syrians gave their blood and life for is achieved,” he says.

For the Syrians who rose up in protest in 2011 and thereafter, Sunday was a triumph that left them wishing for deceased loved ones to be able to witness the moment.

“I can see the joy in people’s faces,” says Radwan, a medical engineer based in Damascus. “The thing we all have now is hope,” he says.

For Syrians, Assad is in the past: ‘The thing we all have now is hope’

Syrians at home and abroad were still reeling Monday because what long seemed impossible – the overthrow of President Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime – took place in just a matter of hours this weekend.

After years of civil war that featured sectarian massacres, intercommunal conflicts, and jihadist violence, Syrian opposition forces that swept into Damascus early Sunday and chased Mr. Assad into exile in Russia are now in control of much of the still-fragmented country.

It’s an inflection point after 53 years of ruthless, repressive Assad family rule, in which people were detained at the slightest hint of dissent.

Syrians displaced by the conflict within the country and abroad exchanged greetings and congratulations as strategic city after strategic city – Aleppo, Hama, and Homs – fell as rebels dashed to the capital. People quickly started dreaming of returning to their homes and reuniting with loved ones.

It will take time to decode the local and international dealmaking that helped make some of this possible.

“I am sleepless and so happy,” says longtime Syrian dissident Anwar al-Bunni. The former political prisoner has been observing events from Berlin, one of the rare European cities that opened its arms to welcome Syrian refugees when they came by the hundreds of thousands from Turkey in 2015 and 2016.

“The goal that Syrians gave their blood and life for is achieved,” he says.

Overthrowing the Assad regime was far from simple and took over a decade at the cost of nearly half a million Syrian lives lost to multifaceted violence. On the regime side, that included the use of crushing military force against protesters; airstrikes by Syria and its key ally, Russia; chemical weapons attacks; the siege and starvation of opposition hubs; and industrial-scale torture.

“I can see the joy in people’s faces,” says Radwan, a medical engineer based in Damascus, who asked that his full name not be used. He adds that the streets are choked with traffic as more and more people venture out. “The thing we all have now is hope,” he says.

A breathtaking fall

Events Sunday were swift and historic. In the hours before dawn, rebels took Damascus with breathtaking speed and without opposition. The once-feared forces of the president’s brother, Maher al-Assad, made no grand last stand.

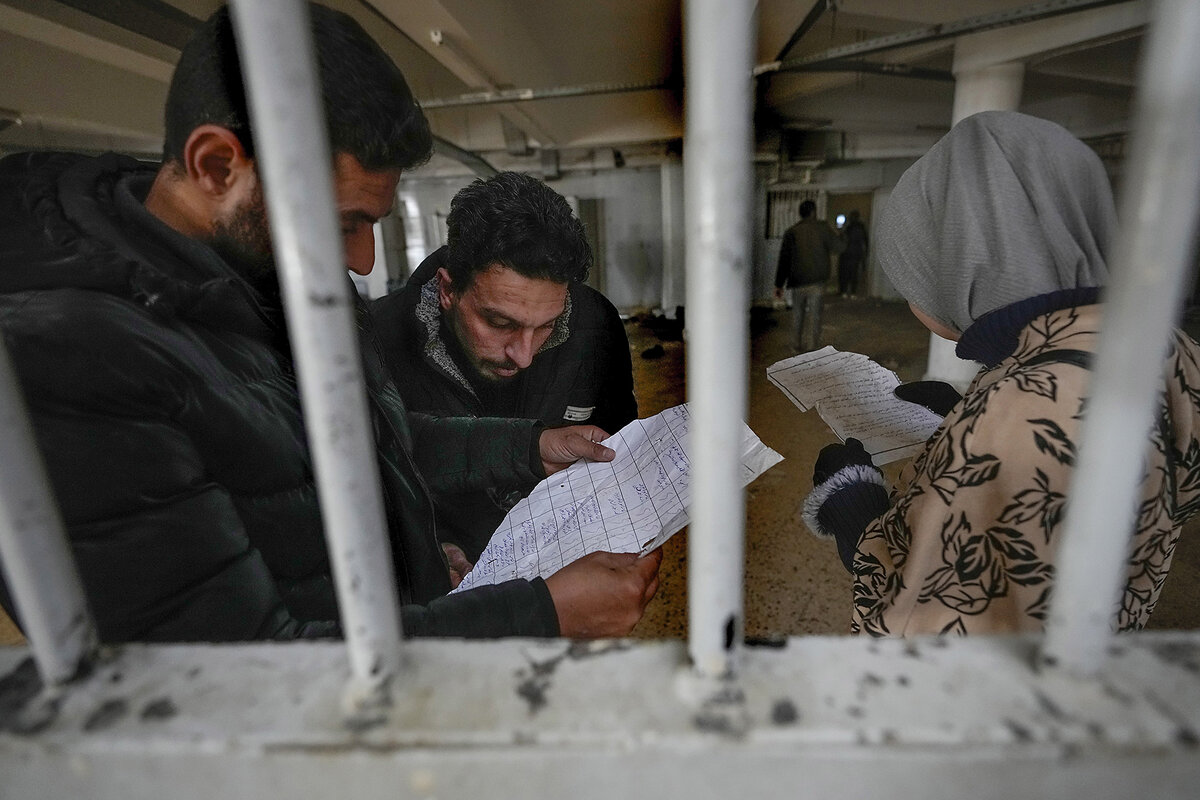

The president fled to Russia, where he was swiftly granted asylum, on “humanitarian grounds.” Prisoners were released from infamous jails turned into death camps and slaughter houses, such as the notorious Saydnaya.

“This is a victory my brothers for the Islamic nation, a new history for the region,” declared Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, leader of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the dominant insurgent faction, in his victory speech Sunday at the Omayyed Mosque in Damascus. He condemned Mr. Assad for giving Iran free rein in the region, spreading sectarianism, and turning Syria into a hotbed for drug trafficking.

Prime Minister Mohammed Ghazi al-Jalali said Sunday he was taking on the role of temporary caretaker of state institutions.

“The prime minister said they will work with the new army,” says Radwan, adding that he has been positively impressed by the rebel forces in town, although their celebratory gunfire terrified everybody. “That needs to be reflected in reality, because they have a lot of things to do.”

Institute for the Study of War and American Enterprise Institute's Critical Threats Project

The swift rebel advance was testament in part, analysts say, to the weakness of the government. It had been abandoned by its traditional allies – Russia, Iran, and Lebanon’s Hezbollah – as well as by Arab nations that in recent years had changed course from their repudiation of the regime’s brutal suppression of dissent and pursued normalization.

But the success “was also the result of careful planning and preparation by HTS,” says Broderick McDonald, associate fellow at the London-based International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation. Mr. McDonald has conducted field work on the evolution of HTS, designated a terrorist organization by the United States, United Nations, and European Union, due to its past links with Al Qaeda.

“Over the past five years, HTS has consolidated its control over rival rebel groups and professionalized its military force,” he says. It did so by investing heavily in training and the establishment of a military academy in Idlib, where it standardized its operations.

It also set up statelike institutions in northwest Syria, including the opposition Syrian Salvation Government, which enabled it to rapidly assume civil administration and deliver services to territories it took over. In Aleppo, HTS deployed the Syrian Salvation Government within hours of capturing the city.

“Through these institutions, HTS hopes to portray itself as a well-organized, responsible actor to both the international community and Syrians,” notes Mr. McDonald.

Born in Saudi Arabia in 1982, Mr. Jolani began his charm offensive in 2021 with a PBS interview. And he granted CNN an interview last week after capturing Aleppo. He says he has moderated, and indeed has kept more radical elements in check, according to analysts, but not everyone trusts that. His speech Sunday was steeped in the language of Islamic holy war. There have been protests over his autocratic style of rule in Idlib, as well.

An array of forces

HTS forces alone are estimated to be 30,000-strong, without counting allied factions. In the north, the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army factions supported the HTS-led offensive on Hama and Homs, while also pursuing their own campaign in eastern Aleppo and Manbij. In Syria’s south, smaller local groups also launched an offensive after the HTS-led offensive in the north began to capture major cities.

“These local groups from the south are not as well organized as HTS but they rapidly captured Daraa and Suwayda and reached the southern outskirts of Damascus before any other group,” notes Mr. McDonald. The relationship between these groups is fractious at best, he says, and all of them will want to play a role in shaping the future of Syria.

Nadim Houry, executive of the Arab Reform Initiative, says HTS reached out to minority communities to reassure them, and credits the group’s success to a mix of strong communication, discipline, and the effective use of locally produced drones.

For the Syrians who rose up in protest in 2011 and thereafter, Sunday was a triumph that left them wishing for deceased loved ones to be able to witness the moment. The revolution that began with peaceful protests will likely go down in history as one of the bravest of the Arab Spring, so tight was the grip of Syrian security services over people’s lives.

Initial slogans at the time called for regime change. It was a calculated gesture that sought to give the autocratic Mr. Assad a chance to clean house and change course. Despite coming to power with promises of political reform and economic liberation, he did the exact opposite. He responded to protests with brutality and fanned sectarian conflict.

As soldiers fired and tanks rolled, people chanted “One, one, one – the Syrian people are one” and “Peaceful, peaceful – the Syrian revolution is peaceful,” before the taboo-breaking “Get out, Doctor.”

Many of those who dared to have that dream and eventually fought for it are dead or are now refugees.

“This victory stirs up joy, yes, but it also rips open my wounds,” says Umm Tamer in the city of Raqqa, who sat out the celebrations due to her emotions and advanced age. Two of her sons were among citizens in opposition hubs who took up arms to defend themselves and died in action.

Concerns about jihadis

Parts of Syria, like Iraq before it, became a magnet and bastion for Sunni jihadis. Today Syria is awash with weapons and armed groups with different geographical and ideological priorities. And in many ways, the force that took power in Damascus is exactly what Mr. Assad, who tried to style himself as a protector of religious minorities, taught supporters to fear.

Sami, the owner of a software company who asked to withhold his surname, shares footage of his office ransacked in an apparently abandoned looting effort. His anxiety was compounded by airstrikes on weapons depots and government installations carried out by Israel, to prevent munitions and sensitive information from falling into the hands of armed groups it does not trust.

“Assad is out now, but we are losing our country, a historical country,” he says. “I will stay here until the airport will open. [Mr. Jolani] looks like a good guy, but I am afraid of the Islamic side. On the media they may look like angels, but on the ground the situation may be different. I hope this is the end [of war], but I know this is the start of a new one” with Israel.

“There is no clear view now on what will happen, but that does not mean we are afraid,” says Mr. Bunni in Berlin. “What’s needed now is a lot of effort for sure. Our battle to build democracy and rebuild the country starts now. ... There is a new dawn, and I hope it will be sunny and shiny for all generations.”

Institute for the Study of War and American Enterprise Institute's Critical Threats Project

News Briefs

Today’s news briefs

• Netanyahu set for trial: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is set to testify Dec. 10 for the first time in a trial against him on corruption allegations.

• Notre Dame reopens: Paris’ Notre Dame reopens its doors for the first time since a fire nearly destroyed the beloved 12th-century cathedral five years ago.

• China investigates Nvidia: China says it has launched an investigation into Nvidia Corp. over suspected violations of the country’s anti-monopoly law, in a move seen as a retaliatory shot against Washington’s latest curbs on the Chinese chip sector.

• Lara Trump steps down: Lara Trump will step down as co-chair of the Republican National Committee as she considers potential options with her father-in-law, President-elect Donald Trump, set to return to the White House.

Patterns

What next for leaderless Syria, once the Mideast’s hub?

Syria’s civil war, which appeared to be dormant, flared into sudden action last week, toppling a 54-year-old dictatorship in a matter of days. What comes next?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

The collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria is the Middle East equivalent of the fall of the Berlin Wall. It left the region’s top leaders trying to come to terms with a historic and dizzyingly sudden turning point that almost no one had foreseen. And it left them powerless to do anything about it.

Instead it was a rebel Syrian army, led by a former Islamist radical who says he has reformed, which rolled into the capital, Damascus, over the weekend, scattering government troops as it advanced.

The rebel fighters were generally welcomed as liberators. Abroad, however, countries such as Russia and Iran, which had propped up the Assad government, were licking their wounds and wondering what comes next. Both have lost strategically important positions that they are unlikely to be able to restore.

Regional leaders are also aware of the cautionary example of other toppled dictatorships, such as Saddam Hussein’s in Iraq and Muammar Qaddafi’s in Libya. Initial outpourings of popular celebration and unity there soon gave way to turf wars and widespread violence.

That may explain President-elect Donald Trump’s social media post: “Syria is a mess. THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT.”

What next for leaderless Syria, once the Mideast’s hub?

The Middle East’s most enduring reign of terror ended suddenly over the weekend, as Syria’s President Bashar al-Assad scurried out of Damascus and sought haven in Moscow.

While his demise came with breathtaking speed, the repercussions are just beginning – for Syria itself, for the rest of the region, and for major outside players including Moscow, Beijing, and Washington.

That’s not just because Syria’s brutal dictatorship has played a central role in Arab politics for decades; Mr. Assad’s father, Hafez al-Assad, came to power in a coup more than half-a-century ago.

It’s because of the manner in which the younger Assad’s 24-year rule ended.

The uprising that forced him out was the work of homegrown rebel armies, advancing inexorably across the country as his troops scattered and Syrians of all ages and faiths celebrated their success.

Outside powers, both those fueling the country’s civil war over the past 13 years and those trying to end it, were left astonished, unsure of what was happening, powerless to affect events, and grappling for an effective response.

It was the Mideast equivalent of the fall of the Berlin Wall: a turning point long hoped for by many, feared by some, expected by very few, and dizzyingly sudden when it came.

The impact was captured in real time by an extraordinary split-screen moment.

Inside Syria, city after city was falling to rebel forces. Street celebrations were in full flow, with guns being fired into the air and people embracing. “Wahad, wahad, wahad, al-shaab as-Souri Wahad!” some chanted. “One, one, one, the Syrian people are one!”

In the Gulf state of Qatar, 1,300 miles away, elite Middle East leaders and influencers were gathering for their annual Doha Forum, under the banner of “Diplomacy, Dialogue, Diversity.”

In fact, diplomats from major Mideast states and the Russian and Iranian foreign ministers – President Assad’s key supporters – found themselves huddling with one another to figure out what was happening in Syria, how rapidly events were moving, and where they were likely to lead.

By late Saturday, they obviously had found no answers. For even as the rebels were advancing on Damascus, the ministers issued a joint statement stressing “the need to stop military operations” and revive a “comprehensive political process” to negotiate an end to the civil war.

Within hours, Mr. Assad was gone.

And just as when the Berlin Wall came down, while the immediate impact is clear, the implications for the years, or even days, ahead are much more uncertain.

The immediate winners are the Syrian people, freed from a regime that jailed and tortured thousands, barrel-bombed and gassed its own population during the civil war, and enriched itself while the economy crumbled.

The losers, beyond Mr. Assad, are the outside powers that rescued him from defeat nine years ago and used their forces to keep his dictatorship afloat: Vladimir Putin’s Russia and Iran, which provided not just direct aid but troops from its Hezbollah proxy army in Lebanon.

Russia may well now lose the bases it established in Syria – a major air force facility and, even more importantly, its warm-water naval port, in Tartus on the Mediterranean coast. Russian mercenary forces backing military coup leaders in Africa have used Tartus as a critical supply point.

Iran has lost its main supply route to channel arms, equipment, and personnel to Hezbollah.

China, too, could pay a price. Beijing steered clear of military support for Damascus. But it blocked international efforts to negotiate an end to the civil war that would have eased Mr. Assad from power. And last year, Chinese leader Xi Jinping welcomed him to Beijing and announced a “strategic partnership.”

Still, the critical question now is what will happen inside Syria – a country splintered into rival militia strongholds by the civil war, and roughly half of whose 23 million people are now refugees inside its borders or abroad.

The largest of the rebel forces that toppled Mr. Assad – Hayat Tahrir al-Sham – has roots in the Al Qaeda and Islamic State jihadist groups.

Yet its leader, Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, broke with them in 2016. Since the start of the advance on Damascus, he has gone out of his way to insist that a post-Assad government must respect and protect all Syrians of all faiths.

So far, his forces seem to have been as good as his word. HTS’s main regional supporter, neighboring Turkey, seems confident that will continue. It is certainly the hope in the Arab world, and in Washington, as President Joe Biden enters his final weeks in office.

And they will be heartened by initial moves to secure an orderly transition to a new government.

Their concern is that HTS’ bedrock Islamist credo, or simply a rank-and-file urge for revenge against the non-Sunni Muslim, Christian, and Druze communities whom the Assad regime courted, might breach Mr. Jolani’s assurances.

There’s also a worry that other groups – including a weakened but still active ISIS – could exploit the political vacuum to try to grab added power and territory for themselves.

Arab political leaders are also aware of the cautionary example of other toppled dictatorships, such as Saddam Hussein’s in Iraq and Muammar Qaddafi’s in Libya. Initial outpourings of popular celebration and unity soon gave way to turf wars and widespread violence.

That may help explain U.S. President-elect Donald Trump’s first public response to President Assad’s fall. “Syria is a mess,” he wrote in a social media post, adding: “THE UNITED STATES SHOULD HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH IT. THIS IS NOT OUR FIGHT. LET IT PLAY OUT. DO NOT GET INVOLVED!”

Whether he will feel the same way when he returns to the White House in January may depend on how it “plays out” – especially whether ISIS, which he took pride in having helped to defeat during his first term, seems resurgent.

There’s a saying among Mideast-based foreign correspondents, used to sum up a sobering lesson that many outside powers have learned about the economic, strategic, and security importance of this often frustratingly unstable region.

“Just because you say you’re through with the Mideast, that doesn’t mean the Mideast is through with you.”

The Explainer

How birthright citizenship could change under Trump

Donald Trump’s campaign featured the issue of unauthorized immigrants. On Day 1, he may try to change their children’s future in the U.S. – against a century of legal precedent.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

-

Caitlin Babcock Staff writer

With limited exceptions, the U.S. Constitution guarantees citizenship to anyone born in America.

President-elect Donald Trump has pledged to end birthright citizenship for children of unauthorized immigrant parents. He told NBC News he hoped to do so through executive action.

An ensuing legal fight could end up before the Supreme Court. The Constitution outlines how it can be amended, and the process involves approval from both Congress and the states.

The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people. The Supreme Court later affirmed birthright citizenship in the case of Wong Kim Ark, who was denied entry back into the United States after a trip to China on the grounds he wasn’t a U.S. citizen.

Some legal minds argue the case did not address the citizenship clause regarding children of unauthorized immigrants.

Mr. Trump says ending birthright citizenship is part of cracking down on illegal immigration, and will take away an incentive for people to enter the U.S. without authorization.

But Jennie Murray, president of the National Immigration Forum, says birthright citizenship is among the “hallmark pieces of the American experiment.” Restricting this right “begins to unwind the definition of what it means to be American.”

How birthright citizenship could change under Trump

Everyone born in the United States, with limited exception, is a U.S. citizen. The Constitution says so.

That’s the legal reading, over a century old, that Donald Trump says he seeks to scrap on Day 1. The president-elect has pledged to end birthright citizenship for children of unauthorized immigrant parents, so that those children born in the country aren’t automatically American.

He confirmed the plan in an NBC interview that aired Sunday.

“We have to end it,” said Mr. Trump. He added that he hoped to do so through “executive action.”

His transition team is starting to draft versions of an executive order, reports The Wall Street Journal. An ensuing legal fight could end up before the Supreme Court. The Constitution outlines how it can be amended – and involves approval from both Congress and the states.

The birthright debate isn’t new. It’s part of a long-term national grappling over the promise and limits of immigration, and what some analysts see as legal questions left unsettled.

How is automatic citizenship a right?

In the U.S. Constitution, Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment leads with this line:

“All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

The country’s concept of citizenship transformed through the Civil War era. In 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that enslaved people weren’t U.S. citizens. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 reversed that decision, establishing U.S. citizenship for people born here regardless of race or past enslavement.

The act was a stepping stone to the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship to formerly enslaved people when it was ratified in 1868. Three decades later, the Supreme Court affirmed birthright citizenship in the case United States v. Wong Kim Ark.

Born in San Francisco to Chinese parents, Wong Kim Ark was denied entry back into the U.S. after a trip to China on the grounds he wasn’t a U.S. citizen. In a 6-2 decision, the justices confirmed that he was.

The Wong Kim Ark ruling has governed the prevailing understanding of automatic citizenship. But some legal minds argue the citizenship clause remains unsettled – especially for children of unauthorized immigrants. That question wasn’t addressed in the Wong Kim Ark case, they argue.

During the NBC interview, Mr. Trump repeated the false claim that only the U.S. has birthright citizenship. Several countries do, including Canada and Mexico.

Why does President-elect Trump want to restrict automatic citizenship?

Mr. Trump casts it as part of cracking down on illegal immigration that swelled under the Biden administration. This includes removing what Mr. Trump calls an “incentive.”

He spoke of ending automatic citizenship leading up to and during his first term, but he never signed an order. During his latest campaign, he released a video vowing to tackle the task anew as part of securing the border.

On Day 1, “I will sign an executive order making clear to federal agencies that under the correct interpretation of the law, going forward, the future children of illegal aliens will not receive automatic U.S. citizenship,” he said. “At least one parent will have to be a citizen or a legal resident in order to qualify.”

The New York Times reported last month that Mr. Trump’s team plans to stop issuing documents like passports and Social Security cards to babies born to unauthorized migrant parents on U.S. soil.

The president-elect has also said he wants to rein in “birth tourism,” in which women come from abroad to birth their babies here. Those schemes exist, and fraudulent operations by Chinese nationals have been prosecuted by the U.S. government. Some Trump critics, however, have called his treatment of “birth tourism” xenophobic.

In 2016, the latest year available, around 250,000 babies were born to unauthorized immigrant parents in the U.S., reports Pew Research Center.

Can Mr. Trump actually change birthright citizenship?

It’s unclear. Any executive order would likely draw a legal fight, and could end up in the nation’s top court. One point of debate, which some legal experts say could prove key, is how to interpret who is “subject to the jurisdiction” of the U.S. – as the law says.

Changing the citizenship clause in the Constitution, however, would require an amendment. That would involve an approval by two-thirds vote from the U.S. House and Senate, and ultimately a ratification by at least 38 states. The last amendment was added in 1992.

Birthright citizenship is among the “hallmark pieces of the American experiment,” says Jennie Murray, president of the National Immigration Forum. Restricting this right “begins to unwind the definition of what it means to be American,” she says, which could be seen as a step too far for some Trump supporters.

Former immigration judge Andrew Arthur underscores that entering the U.S. without authorization is a crime. The citizenship benefit “creates a pull factor,” he says. “And generally, we try to eliminate those incentives from our law.”

Automatic citizenship is a “question that needs to be resolved in the Constitution,” says Mr. Arthur, law and policy fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies. He notes there’s already an exception to whom the Fourteenth Amendment citizenship clause applies: children of foreign diplomats.

Hiroshi Motomura, co-director of the Center for Immigration Law and Policy at UCLA School of Law, thinks it’s unlikely the Supreme Court would overturn Wong Kim Ark. That’s because while possible, he says, that would reverse more than a century of precedent.

South Koreans say fight for democracy is not over

South Korea’s relatively young democracy proved its resilience last week when lawmakers shut down the president’s attempt to impose martial law. But he remains in power – at least on paper – revealing the challenges still facing the country.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 6 Min. )

After President Yoon Suk Yeol’s short-lived imposition of martial law on Dec. 3, South Koreans of all ages have poured into the streets to send a message: There is no going back to the military rule and repression of the 1980s.

A noodle vendor calls the incident embarrassing. A taxi driver says he regrets voting for Mr. Yoon. An IT professional says the president’s apology on Saturday was too little, too late.

Even Mr. Yoon’s backers – less than 20% of South Koreans now, polls show – stress he must protect democratic institutions.

“These incidents tell us that people are internalizing democratic norms,” says Myunghee Lee, a political scientist focused on East Asia.

But South Koreans are also expressing frustration over the political gridlock that preceded the martial law attempt. And the crisis of legitimacy unleashed by Mr. Yoon must still be resolved, with the president surviving an impeachment vote this weekend after members of his party walked out.

Park Jung Min, a shipping company worker from the southern city of Geoje, traveled five hours to attend a rally Saturday calling for the president’s removal – her first political protest. She says she’ll make the trip to Seoul again this week.

“Our national character is we never give up,” she says.

South Koreans say fight for democracy is not over

At Seoul’s traditional Namdaemun market, vendor Jang Chang Suk closely guards her knife-cut noodle recipe – but freely dishes out her views on South Korea’s current political crisis.

“It’s embarrassing,” she says of President Yoon Suk Yeol’s short-lived imposition of martial law Dec. 3, which has plunged the country into turmoil. But Ms. Jang’s dismay is matched by confidence that her fellow citizens will uphold South Korea’s democracy.

“South Koreans are good people. They have it together – they’re on it,” she says, slicing fresh wheat dough with quick strokes of a cleaver and wiping her hands on her flower-print apron. In contrast, she says, “the government is lagging behind.”

Indeed, across South Korea, people of all ages have poured into the streets in massive numbers in recent days to send the message that there is no going back to military rule and its dark legacy of repression from the 1980s. Even Mr. Yoon’s backers – less than 20% of South Koreans now, polls show – stress he must protect democratic institutions.

“These incidents tell us that people are internalizing democratic norms,” says Myunghee Lee, an assistant professor at James Madison College of Michigan State University. “The absolute red line is using the military to suppress the opposition. That is not acceptable.”

Still, Dr. Lee, a political scientist focused on East Asia, says the country’s democratic system has a long way to go. While buoyed by their success in drawing that line, many South Koreans are also expressing frustration over political gridlock that preceded the martial law attempt. And the crisis of legitimacy unleashed by Mr. Yoon must still be resolved, with the embattled president surviving an impeachment vote this weekend.

“South Korean democracy is at a ceiling,” she says. So far, “it’s not breaking that ceiling.”

Swift political fallout

In a bustling, concrete-and-glass coffee shop in downtown Seoul, IT professional Je Min Hwang pauses when asked who he’d favor to lead South Korea.

He backs the opposition center-left Democratic Party, but its leader, Lee Jae-myung, is “not 100% clean” either, Mr. Hwang says.

Mr. Lee was convicted last month by a Seoul court for violating election laws, a ruling he says he’ll appeal. An even bigger concern for Mr. Hwang is the polarizing, acrimonious campaign led by Mr. Lee since his party expanded its parliamentary majority in April to discredit Mr. Yoon and his ruling People Power Party (PPP).

“They are butting heads,” Mr. Hwang says of South Korea’s two leading political parties. “There should be compromise.”

The desire for less contentious politics is widespread among South Koreans.

An Jung Min, a clothing importer, says he dislikes both Mr. Lee and Mr. Yoon, and voted for neither of them in the 2022 presidential election, which Mr. Yoon won by a razor-thin margin.

“The current president doesn’t know how to negotiate or collaborate – he’s very stubborn,” says Mr. Min.

As both sides dug in, Mr. Yoon drastically escalated the showdown on Dec. 3 by declaring martial law – banning all political activities and threatening violators with arrest, putting all media under military control, and prohibiting rallies.

Mr. Lee immediately rushed to the National Assembly building – climbing a wall to get in as troops tried to seal off the parliament – and led a vote to oppose military rule. A few hours later, Mr. Yoon backed down and lifted the order.

The public backlash and political fallout have been swift and catastrophic for Mr. Yoon. Last Thursday, then-Defense Minister Kim Jong-Hyun resigned, only to be arrested on Sunday for his role in the martial law decision.

Military commanders distanced themselves from Mr. Yoon, testifying that the martial law attempt was rushed and disorganized, and military veterans – many of whom had supported the president – turned out to condemn him.

South Korea’s stock market hit a one-year low, and its currency slid to a 15-year low against the dollar on Monday, matching the political fortunes of Mr. Yoon, whose popularity rating sank into the teens.

“I voted for the wrong person,” says Seoul taxi driver Mr. Shin, withholding his first name to protect his privacy.

Mr. Yoon’s martial law fiasco shocked him.

“This is not the 1980s – it’s 2024!” he says, referring to the 1980-to-1987 dictatorship of Chun Doo-hwan, who imposed martial law and ordered the brutal crushing of a democratic uprising in May 1980. “In the old days, you could block the media and the roads. But these days, every citizen is a reporter. These days, if a soldier was ordered to shoot civilians, he would disobey.”

On Saturday, facing an impeachment vote by parliament, Mr. Yoon offered a televised apology, followed by a deep bow. But many South Koreans rejected the mea culpa as too little, too late. “It lacked sincerity,” says Mr. Hwang.

President evades impeachment

Ki-Soo Lee, a Seoul kindergarten staff person, was putting her 10-year-old son to bed last Tuesday when the phone rang. A friend frantically told her the president had declared martial law.

“We were all asking, ‘What should we do?’” Ms. Lee recalls. Thoughts raced through her head. Her husband was in the hospital – should she leave her son at home? Overhearing, her son chimed in.

“Umma,” he told her, “under the bed is the best place to hide!”

Ms. Lee says she’s grateful the decree was overturned so quickly, amid large-scale protests. “I believe in the strength of the South Korean people,” she says, clasping her hands together in a sign of solidarity. Now, she says, Mr. Yoon should resign.

“I want the president to realize what he did and step down. If that is not possible, the citizens of South Korea will help him step down,” she says.

The next day, Ms. Lee joined more than 100,000 people from all over South Korea who thronged to the National Assembly to call for impeachment. Chanting and singing, they huddled together, lighting candles as dark descended and it grew bitterly cold. A few hundred Yoon supporters rallied nearby.

As the vote neared, however, Mr. Yoon’s ruling PPP members stood up and filed out – their boycott making the vote impossible. “Go back,” the protesters chanted, calling the boycotting PPP members by name.

Later, in what experts called a highly unorthodox arrangement, PPP leader Han Dong-hoon said the party, together with Prime Minister Han Duck-soo, were taking over responsibility for “state affairs.” Mr. Yoon would no longer be involved in governance or foreign affairs, essentially losing legitimacy while remaining president. On Monday, South Korea’s justice ministry reportedly barred Mr. Yoon from leaving the country.

“The party should not be ruling, because that’s not what the Constitution says,” Dr. Lee says. “This is not great for South Korean democracy.”

Many South Koreans like Park Jung Min believe Mr. Yoon must go. “Our national character is we never give up,” says Ms. Park, a shipping company worker from the southern city of Geoje who traveled by bus for five hours to come to Saturday’s rally – her first political protest.

“It’s in our instinct and our blood,” she says. “I will come back [to protest] next week.”

How a revered starchy side dish helped choose Ghana’s next president

Economic issues have been the deciding factor in many of the world’s elections this year. In Ghana, the rising cost of its most beloved food helps explain why voters decisively ousted their ruling party on Saturday.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Justice Baidoo Contributor

Want to understand why opposition candidate John Mahama was elected president of Ghana this weekend?

Look no further than the country’s favorite food, a fermented starch made from corn called kenkey.

“The prices of kenkey have skyrocketed, and people are unable to afford” it, Mr. Mahama told the crowd at a campaign rally Nov. 13. More generally, ballooning food prices have contributed to the worst cost-of-living crisis in Ghana in decades, an issue that was top of mind for voters.

But by invoking the revered starch in particular, Mr. Mahama was also participating in a long-established “part of our political tradition,” explains Kobina Aidoo, a researcher and creator of The Kenkey Index, a kind of Ghanaian Big Mac Index. “Many people will ask the question when they hear all the macroeconomic numbers, ‘What has that got to do with the price of kenkey?’”

How a revered starchy side dish helped choose Ghana’s next president

Vapor from the silver cooking pot billows upwards, so hot that even several feet away, it feels like you are standing in front of an open oven. But Esther Nunoo doesn’t flinch as she leans over to check the rounds of dough bobbing in the boiling water.

Ms. Nunoo is making kenkey, the sticky balls of fermented corn flour that are one of Ghana’s most beloved foods. Served on the side of nearly every popular dish here, kenkey is so embedded in Ghanaian identity that it features in local folklore and even pop music.

And this weekend, it helped pick the country’s next president.

On Saturday, Ghanaians elected opposition candidate John Mahama, who previously served as president between 2012 and 2017.

As was the case in elections around the world this year, many Ghanaians voted with their pocketbooks. The cost of living has been rising sharply here for the last four years. And that’s visible nowhere more than in the ballooning costs of everyday food staples, an issue that was top of mind during the campaign season.

“The prices of kenkey have skyrocketed, and people are unable to afford” it, Mr. Mahama told the crowd at a rally for his National Democratic Congress (NDC) party on Nov. 13.

By invoking the unaffordable cost of the revered starch to explain why voters should choose him, Mr. Mahama was participating in a long-established “part of our political tradition,” explains Kobina Aidoo, a researcher and creator of The Kenkey Index, a kind of Ghanaian Big Mac Index. “Many people will ask the question when they hear all the macroeconomic numbers, ‘What has that got to do with the price of kenkey?’”

A protest vote

Only two hours after the polls closed on Saturday, thousands of people had already poured into the streets of Jamestown, the coastal Accra neighborhood where Ms. Nunoo runs her small restaurant serving kenkey and fried fish.

The votes hadn’t yet been tallied, but the crowds marched past her restaurant carrying a coffin draped in the red, white, and blue colors of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP).

“Now we can’t even [afford to] buy kenkey, our own food,” says Leonard Copson, one of Ms. Nunoo’s regulars, explaining why he voted for Mr. Mahama.

The next day his opponent, Vice President Mahamudu Bawumia, the NPP candidate, officially conceded.

“This is a protest vote,” explains Godfred Bokpin, an economist and head of the University of Ghana Business School. “People have opted to punish the government’s failure to admit reality.”

For Ms. Nunoo, the reality is that business is the worst it has ever been in the last four decades. Ingredients are more expensive, and customers have less money. In 2021, she says she sold a ball of kenkey, which comes wrapped in a banana leaf, for 2 Ghanaian cedis (about 13 cents). Today, the price is more than twice that, 5 cedis, which is in line with national figures gathered by The Kenkey Index.

The price hikes were so visible, and so alarming, that Mr. Mahama shouted them out on the campaign trail. And when he did so, he drew on a long political tradition of using kenkey prices as a shorthand for economic crisis.

In 1981, opposition leader Kwaku Baah famously pulled a ball of kenkey from his briefcase during a budget debate, waving it around as he explained how the government’s policies had hurt Ghanaian consumers. In 2012, President John Atta Mills made an unannounced visit to a market in Accra to buy kenkey – and by doing so prove that prices weren’t rising as quickly as his political opposition claimed.

For Mr. Mahama, it was easy to make the link between kenkey prices and his opponent.

The NPP “told us we were sitting on money,” he said during the same rally where he spoke of kenkey price inflation. Instead “we’re faced with severe hardships and battling debts.”

He was referring to the massive economic crisis that Ghana has weathered over the last few years. As recently as 2019, the country was the fastest-growing economy in the world, spurred by increasing prices of gold and cocoa, its major exports, and growth in its manufacturing sector.

But then came the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which caused a surge in the prices of food, fuel, and fertilizer. Meanwhile, after years of out-of-control borrowing and high interest rates, national debt was ballooning, and the economy went into a tailspin. Inflation hit 54% by the end of 2022.

In December 2022, Ghana officially defaulted on much of its debt, forcing it to approach the International Monetary Fund for a $3 billion bailout. As a result of the debt restructuring that followed, many middle class Ghanaians had to exchange their government savings bonds for new ones with lower yields and longer maturity timelines.

A wide disconnect

But for the average Ghanaian, the crisis was felt most acutely in their shopping baskets. Between February 2023 and February 2024, for instance, the cost of eggs and tomatoes more than doubled, according to the Ghana Statistical Service. Meanwhile, poverty in the country is on the rise.

For decades, Ms. Nunoo made her kenkey by running dried ears of corn through an enormous electric grinder. Then she mixed the powder with several gallons of water and left it to ferment, creating a thick dough.

Now, she can no longer afford the electricity costs for the grinder, or the cost of water for producing the mixture. So she buys her dough pre-made, only doing the last step, wrapping and boiling the kenkey balls, herself.

“Politicians always promise honey and give us nothing but this particular government is killing us,” she says.

So when the time came to cast her ballot last week, the decision was easy. She voted for Mr. Mahama.

Indeed, the once-and-future president campaigned heavily on his plans to fix the cost-of-living crisis and create more jobs.

Ironically, he himself was voted out of office in 2016 after a single term in part for failing to deal with economic issues like falling commodity prices and an electricity supply crisis.

“It’s not like we do not remember [the NDC’s] issues,” says Professor Bokpin. But in this election, people were more angry with the “wide disconnect between [the NPP] and the reality on the ground.”

In Jamestown, Ms. Nunoo reacted to the election result with the same unbridled joy as her customers, even shutting down the restaurant early to celebrate. But her hopes for the future are more muted.

“I think that with the new president, things will be slightly better,” she says.

In Pictures

This Delhi cop wants to ‘spread goodness.’ He set up a school.

About a third of India’s school-age children don’t attend classes. In Delhi, impoverished kids are learning to love reading and math, thanks to a police officer’s makeshift school.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 3 Min. )

-

By Shefali Rafiq Contributor

-

Saqib Mugloo Contributor

It wasn’t until Than Singh came along that learning became a favorite pastime for the children who typically roam Delhi’s streets begging, rifling through garbage, or engaging in petty crimes.

In 2015, the Delhi police officer started a pathshala, or place of learning, where he teaches 80 students a day in a temple set up near the Red Fort. “It was heartbreaking to see children scavenging for plastic bottles in the trash,” he recalls. “That’s when I decided to do something.”

More than half of India’s children are malnourished, and about 30% of those ages 6 to 18 don’t attend school. Mr. Singh, who grew up poor in northwestern Rajasthan state, is determined to change these statistics. “My dream is to see every underprivileged child in school,” he says with a broad, charming smile.

He starts his day early, patrolling the busy lanes of Old Delhi, the capital’s historic heart, as part of his duties. But every day after work, he holds classes at his pathshala, where students eagerly await him. Initially, only four children attended Mr. Singh’s pathshala. Nine years down the line, he has now taught hundreds.

Expand the story to see the full photo essay.

This Delhi cop wants to ‘spread goodness.’ He set up a school.

For the children living in impoverished areas in the shadow of Delhi’s Red Fort, education was once a distant priority. Their homes are tarpaulin-covered sheds that stand on bamboo sticks, and their parents have few resources. To survive, many of the children beg on the streets, scavenge through trash, or engage in petty crimes.

It wasn’t until Than Singh came along that reading and math became the children’s favorite pastimes. In 2015, the Delhi police officer started a pathshala, or place of learning, where he teaches 80 students a day in a temple set up near the Red Fort. “It was heartbreaking to see children scavenging for plastic bottles in the trash,” he recalls. “That’s when I decided to do something.”

More than half of India’s children are malnourished, and about 30% of those ages 6 to 18 do not attend school. Mr. Singh, who grew up poor in northwestern Rajasthan state, is determined to change these statistics. “My dream is to see every underprivileged child in school,” he says with a broad, charming smile, adding that he is confident that, with God’s help, he will make it happen.

He starts his day early, patrolling the busy lanes of Old Delhi, the capital’s historic heart, as part of his duties. But every day after work, he holds classes at his pathshala, where students eagerly await him. Among them are Ajay Ahirwar and Neelu Ahirwar (no relation).

Ajay says he aspires to become a high-ranking officer in the government so that he can improve the conditions of his family and those living like him. Neelu is fond of her teacher and the pathshala. “I would rather be here, even on holidays, than at home,” says the young girl, who aspires to become an officer in the Indian Police Service.

Initially, only four children attended Mr. Singh’s pathshala. He contributed money from his salary to buy books, notebooks, pencils, and schoolbags. Nine years down the line, he has now taught hundreds of children.

“Beyond basic lessons, I try to instill manners and discipline in these students,” Mr. Singh says. “Even if they come to this school just for a meal, I’ll be happy because, seeing others, they may also want to study.”

Mr. Singh organizes extracurricular activities, too, including cricket. For those children who do attend school in the city, he celebrates good exam results at his pathshala. “I just want these children to stay away from all the bad influences they’re vulnerable to,” he says, referring to the crimes that affect Delhi.

“Our aim in the world is to spread goodness and happiness. The rest, God will take care of.”

For more visual storytelling that captures communities, traditions, and cultures around the globe, visit The World in Pictures.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Longings for home drove Syria’s liberation

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Since Dec. 8, when a dictatorship in Damascus fell to a rebel group, many of the more than 12 million people displaced by Syria’s conflicts have probably told their loved ones, “We are going home.”

“I feel like I’ve been born again,” said Maysaara, a refugee in Belgium, packing his bags. “I prayed to live long enough to see this day.”

That longing for home was always a strong sentiment among the more than half of Syria’s population that was displaced by 13 years of war. It may also have been a strong reason the Assad regime crumbled so quickly. “To the displaced all over the world, free Syria awaits you,” one commander, Hassan Abdul Ghani, posted on X after the regime’s collapse.

The desire for home – as a place of safety, a reflection of dignity, and an expression of family affection – often can influence a conflict in subtle ways. For Syrians, home before the war started was seen “as enriching multigenerational relationships with family and friends, intertwined with culture, faith, a love of place,” according to a 2023 study.

For countless Syrians preparing to return to their communities, the journey is a path not just to a place, but to spiritual renewal.

Longings for home drove Syria’s liberation

Since Dec. 8, when a long dictatorship in Damascus fell quickly to a rebel group, many of the more than 12 million people displaced by Syria’s conflicts have probably told their loved ones, “We are going home.”

“I feel like I’ve been born again,” Maysaara, a refugee in Belgium, told The New Yorker, packing his bags. “I prayed to live long enough to see this day.”

That longing for home was always a strong sentiment among the more than half of Syria’s population that was displaced by 13 years of war and lived either inside Syria or as refugees from Turkey to Europe to Canada. It may also have been a strong reason the Assad regime crumbled so quickly.

“To the displaced all over the world, free Syria awaits you,” one commander, Hassan Abdul Ghani, posted on X after the regime’s collapse.

The desire for home – as a sanctuary, a place of safety, a reflection of dignity, and an expression of family affection – often can influence a conflict in subtle ways. Nearly 120 million people – not quite half of the global migrant population – have been displaced by conflict, violence, or natural disasters. Less noticed are the streams of people returning home. In 2023 alone, 6.1 million displaced people returned to their areas or countries of origin, according to the International Catholic Migration Commission. Many do so voluntarily, to rebuild and restore.

The desire to return home underscores that home is not just a place. For Syrians, home before the war started was seen “as enriching multigenerational relationships with family and friends, intertwined with culture, faith, a love of place,” according to a 2023 study published in Wellbeing, Space and Society.

“Beyond the family,” the study found, “Syrian men and women described social networks where faith was central and included close friendships with neighbors and community members and which reflected values and a way of life where others could be depended upon for support and care.”

In Arab societies, Muslim and Christian alike, home is also vital to a spiritual obligation of hospitality – “generosity of spirit ... which defines humanity itself,” observed Mona Siddiqui, professor of Islamic and Interreligious Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

The rebel forces that have toppled the regime of Bashar al-Assad have struck chords of reconciliation. The new leadership has granted a general amnesty for “crimes” committed before Dec. 8, signaling the release of an estimated 150,000 people detained by the fallen regime – many on the pretense of criticizing the state. The rebels have also vowed to protect the rights of religious minorities.

But for countless Syrians preparing to return to their communities, the journey is a path not just to a place, but to spiritual renewal. As a very diverse nation now tries to find national unity, it may find it in that special desire for belonging that defines the Syrian people.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

What makes us new?

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Jenny Sawyer

If we’re feeling burdened or dispirited, we can count on God, divine Life itself, for fresh hope, healing, and progress.

What makes us new?

It’s that time of year when a frequent refrain is that everyone is “over it.” They’re ready for a fresh start, a new leaf.

“I’m tired of everyone and everything,” read a post on social media. “Bring on the new year.”

It raises a thought-provoking question. What makes us new? The inexorable march of time? Our efforts to reinvent ourselves when the calendar tells us to?

A hymn in the “Christian Science Hymnal” flips the script when it says, “O Life that maketh all things new” (Samuel Longfellow, No. 218), indicating that the ceaselessness of divine Life, a Bible-based name for God, is the ever-present renewing power. It restores, regenerates, and brings freshness to our lives – no matter the season.

More than anyone else, Christ Jesus proved this power of God, Life, to renew and redeem. In his presence, those who’d done wrong found they could do differently – and feel a cleansing, life-restoring sense of being forgiven. Those whose bodies were broken or diseased found healing – and a life-affirming freedom.

And yet, even more foundational than the healings was the entirely new view of Life that Jesus revealed to humanity. He called it the kingdom of heaven, and everywhere he went, he greeted people with the news that this kingdom is already here – “at hand” (Matthew 4:17). Just think of the hope, the joyful feeling of newness, that must have bubbled up in his listeners’ hearts when they heard these words. The wait was over. Heaven was here!

Even the smallest acknowledgment of this spiritual reality must have set their lives on a brand-new trajectory. God was no longer far off and abstract, but the living Love that they could experience today.

And so, too, it is for us. We are promised that “of his kingdom there shall be no end,” as the angel says to Jesus’ mother, Mary (Luke 1:33). While it may seem as though our lives are wrapped up in timelines, limitations, and all the other traps and trappings of mortality, the opposite is true. We aren’t mortals destined to an early peak and then inevitable decline, but Life’s own expression – wholly spiritual, and therefore perpetually new. It’s the Christ that makes this evident to us and compels us to live more fully from this basis.

The discoverer of Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy, identified Christ not as the man Jesus, but as “his divine nature, the godliness which animated him” (“Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” p. 26). This animating power of Life is just as present now, and just as actively makes this heavenly kingdom apparent to us. And because this is God’s power, not something self-generated, we can depend on it to continually bless us with a renewed sense of things – sometimes even before we ask.

That was the case for me last December when I was feeling burdened and run down during the last gray weeks of the year. One afternoon while I was out running errands, I felt impelled to take a moment to do a favor for a stranger. Honestly, it didn’t seem like a big deal, yet with that act I felt a tide of newness rise up and wash over me. Gone were the end-of-year blahs. I felt utterly restored – and that feeling carried me into the New Year.

What happened? I think Mrs. Eddy explained it best when she wrote, “... Love alone is Life” (“Poems,” p. 7). As I experienced that day, one of the ways Life makes us new is through love – through not only feeling the presence of divine Love but also living love ourselves.

Can we think of anything more valuable – or more transformative – for the world? To know that we not only reside in God’s kingdom now but that we can live and love the way citizens of this kingdom do? It’s this deeply Christian love that brings hope to the world-weary, healing to the heavy-hearted, and the promise of progress to the fearful and dispirited who are wondering if there’s even a way forward.

Newness, it turns out, is guaranteed. Our prayers can reassure us that since we are actually Life’s expression, God’s spiritual likeness, newness is indeed innate to our lives – because it is Life itself that makes us, everyone, and all things new, no matter the need or the season. We can count on it.

Adapted from an editorial published in the Dec. 9, 2024, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel.

Viewfinder

Top brass

A look ahead

Thank you for joining us today. Please come back tomorrow, when Dina Kraft travels to areas of Israel that have been largely abandoned for more than a year to see if residents will return under the new ceasefire with Hezbollah.