- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Why is Christian Science in our name?

Our name is about honesty. The Monitor is owned by The Christian Science Church, and we’ve always been transparent about that.

The Church publishes the Monitor because it sees good journalism as vital to progress in the world. Since 1908, we’ve aimed “to injure no man, but to bless all mankind,” as our founder, Mary Baker Eddy, put it.

Here, you’ll find award-winning journalism not driven by commercial influences – a news organization that takes seriously its mission to uplift the world by seeking solutions and finding reasons for credible hope.

Explore values journalism About usMonitor Daily Podcast

- Follow us:

- Apple Podcasts

- Spotify

- RSS Feed

- Download

TODAY’S INTRO

A young Monitor reader, impelled to act

Favour Odenyi is a high school senior in San Francisco who enjoys coding and fixing bicycles. She’s also a fairly new reader of the Monitor because of an assignment for a youth leadership program.

At first, Favour wasn’t thrilled. She admits feeling “numb” to the news. And she’s hardly unique. A poll conducted last year by Media Insight Project found that while a majority of 16-to-40-year-olds read the news daily, only 32% enjoy it.

As she started her assignment, Favour found reading the Monitor challenging. The war in Ukraine had just broken out, and world events were confusing. But slowly, she started to feel something else: hope. She was intrigued by an effort to preserve old-growth forests and by an Army chaplain who encourages soldiers to be ethical leaders. She felt drawn in by an article about an Eritrean family who struggled to get asylum in Israel but eventually found a place to live in Canada with a Jewish family. Favour found she wasn’t content to just read the news; she felt impelled to act.

There was a boy in her Advanced Placement calculus class who was struggling with their group project and hardly participating. “I decided to see if what I was reading was actually useful,” recounts Favour. Instead of just keeping to herself as she normally does, she offered to help after class. Then they sat together at lunch and chatted. “I was putting into practice what I was learning in the Monitor,” she says. “Like, just open up a little bit, just the same way that family opened up to complete strangers. It was definitely a big step on my end.”

Favour wrote about her experience reading the Monitor in an award-winning essay sponsored by DiscoveryBound, a national youth leadership program for Christian Scientists. “A transformation was happening,” Favour writes, “one that enabled me to explore how I could apply the values gained from reading the news, in my daily life.” You can read Favour’s full essay here.

Share this article

Link copied.

Help fund Monitor journalism for $11/ month

Already a subscriber? Login

Monitor journalism changes lives because we open that too-small box that most people think they live in. We believe news can and should expand a sense of identity and possibility beyond narrow conventional expectations.

Our work isn't possible without your support.

The Explainer

Are banks – and your money – safe? Five questions.

The failure of two U.S. banks in recent days poses a test of confidence – and of regulatory reassurance – at a time when the economy is already challenged by inflation and rising interest rates.

The failure of two U.S. banks within the past week does not constitute a banking crisis. Instead, it’s a worrying spark of fear that has been spreading. And it’s raising lots of questions.

What should average U.S. bank customers know? The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) insures nearly all banks, guaranteeing your deposits of up to $250,000 (or $500,000 for joint accounts). If you have more than that at any one bank, spread it around to other insured financial institutions.

For investors, the outlook is more uncertain. Investment risk has gone up as a result of the two bank failures. Whether it has peaked is unknown. The biggest U.S. banks – those considered “too big to fail” – look far stronger financially than they did during the 2008 financial crisis.

But some financial experts worry about the precedent set on Sunday when regulators bailed out all depositors at the failed Silicon Valley Bank, rather than just those with $250,000 or less in their accounts. Regulators may be hard-pressed to deny equal protection in future bank failures, even though it could be very expensive for the FDIC. For our full bank explainer, explore the deep-read version of this story.

Are banks – and your money – safe? Five questions.

The failure of two U.S. banks within the past week does not constitute a banking crisis. Instead, it’s a worrying spark of fear that has been spreading. Consumers wonder whether their money is safe.

Some small businesses, especially tech startups, are scrambling to find new banks that can meet their needs such as making payroll.

How far the problem spreads will depend on the trajectory of the economy as well as on consumers’ confidence in their banks. For clues, watch the stock market, analysts say. If bank stocks fall further, that could signal trouble ahead for the economy.

What happened?

Last Wednesday, Silicon Valley Bank, based in Santa Clara, California, announced it had sold some of its assets at a loss and would sell new shares of itself to boost reserves. That triggered SVB customers to begin pulling out their money, causing a run on the bank. By Friday, regulators had taken over the bank.

The collapse of SVB panicked depositors of New York-based Signature Bank, who began withdrawing their money Friday. By Sunday, regulators had taken it over as well. These were the second- and third-largest bank failures in U.S. history, topped only by the 2008 collapse of Washington Mutual in the financial crisis. Both banks were unusual in that they had concentrations of customers in struggling industries: tech startups in the case of SVB; and holders of digital money, known as cryptocurrencies, in the case of Signature.

How close are we to a banking crisis?

It depends on what lens you’re looking through: history or today’s banking structure. One of the lessons of history is that nations don’t need to see a full-blown panic – such as runs on numerous banks à la 1930s – to experience a banking crisis. A 2020 study of banking debacles in 46 countries going back to 1870 found that a 30% average decline in the stock prices of a nation’s major banks typically led to a recession three years later and a sizable decline in overall lending. Through Monday, the S&P Banks Select Industry Index had fallen nearly 23% this month. William Isaac, former head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC), told Politico he expects more banks to fail.

The flip side of that dire outlook is that the banks that might fail this time are likely too small to bring down the banking system. The biggest U.S. banks – those considered “too big to fail” – look far stronger financially than they did in 2008, when the financial crisis forced the federal government to bail out many of them. This time, while aiding depositors, regulators did not bail out SVB or Signature, and the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Justice Department reportedly are investigating SVB.

What should you do?

If you’re an average bank customer, relax. At any FDIC-insured institution (nearly all banks) your deposits are guaranteed for up to $250,000 (that’s $500,000 for joint accounts). Those totals apply whether money is in savings, checking, or certificates of deposit. If you have more than that at any one bank, spread it around to other insured financial institutions. If you’re a small-business owner, who does keep more than $250,000 at a single bank, diversify.

For investors, the outlook is more uncertain. Investment risk has gone up as a result of the two bank failures, but whether it has peaked is unknown.

Should regulators have foreseen the problems?

Hindsight is, of course, 20/20. Still, many observers say regulators missed the boat, especially with SVB. They should have seen that the bank’s assets were too concentrated in U.S. government bonds. While those bonds were rock solid in an accounting sense, they were losing value in the marketplace because they were bought before the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates. The value of old bonds always goes down when interest rates rise because investors prefer buying new bonds that earn a higher rate. As onetime chief economist of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, Charles Calomiris says he urged regulators to consider the market value of a bank’s assets, not just the accounting value. But “it’s so contrary to their culture that they just don’t do it,” he says.

What happens now?

Time will tell whether regulators have calmed depositors to the point that there will be no more bank runs in the coming months. Instead of bailing out the banks, regulators rescued their depositors. That itself was a controversial move, but one that many economists saw as necessary under the circumstances to stem a potential spread of fear about the safety of banks. Big depositors at both banks were relieved.

“Folks would have certainly appreciated maybe a little bit earlier reassurances” from the government, says Ruben Izmailyan, co-founder and CEO of Quiltt Inc., a Dallas-based fintech firm that had big deposits at SVB. But had regulators and the Biden administration not acted, hundreds of tech startups might have been at risk.

Some financial experts worry about the precedent set by bailing out all depositors at a bank, rather than just those with $250,000 or less in their accounts. Regulators will be hard-pressed to deny equal protection to big depositors the next time a bank fails, even though it could be very expensive for the FDIC.

And Mr. Calomiris, now a Columbia Business School professor, is critical of the Biden administration’s new lending program for other banks potentially facing runs by depositors. “It can’t possibly work,” he says, if regulators base those loans on the par value, rather than on the market value, of government bonds that the banks hold. The plan calls for institutions to repay those loans in a year, when, if anything, the bonds will likely be worth even less.

The Fed has its own conundrum when its rate-setting committee meets next week. Should it raise interest rates and continue its aggressive fight against inflation? Or is it wiser to pause, given the jittery state of investors? Year-over-year inflation rose at a slower rate last month than at any time since September 2021. But at 6%, it remains stubbornly high.

Trump weakening? Not judging by his Iowa swing.

Since launching his bid for the White House last year, Donald Trump’s grip on the GOP was widely proclaimed to be weakening. But that belies a set of strengths that are in many ways now becoming evident.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 7 Min. )

Since launching his third bid for the White House some four months ago, Donald Trump’s campaign has frequently seemed fizzling and unfocused. The former president is juggling distractions in the form of mounting legal troubles and the threat of indictment. After many of his candidates lost in the 2022 midterms, his grip on the GOP was widely proclaimed to be weakening.

But those factors belie a set of strengths that are in many ways now becoming evident.

As the contours of the 2024 primary battle start to come into focus, Mr. Trump is already benefitting from some of the same circumstances that helped him in 2016. A large, unwieldy Republican field that divides the anti-Trump vote. Opponents too afraid to attack him directly. Above all, a set of diehard fans who are providing him with a solid, unshakeable floor of support.

At the same time, it’s becoming clear Mr. Trump is bringing an entirely different level of political and professional experience to this primary process than in 2016. He’s wooing key officials for endorsements and behind-the-scenes support. And he’s wasting no time building an on-the-ground apparatus in early voting states that could give him a significant edge over his GOP rivals.

“You’d be foolish to underestimate Donald Trump,” says Luke Martz, a Republican strategist based in Iowa.

Trump weakening? Not judging by his Iowa swing.

Braving the cold March Iowa wind, Patty Havill stands amid a snaking line of red MAGA hats and flag-themed costumes, waiting to see the one man she believes can still save America from all its problems. Other Republican presidential hopefuls have been through town recently – including, on Friday, hot-ticket Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis – but Ms. Havill is single-minded in her devotion. For her, it’s Donald Trump or no one.

“Our country is in chaos. We need him to straighten it out,” says the retired nurse. “Trump is the only one.”

Since launching his third bid for the White House some four months ago, Donald Trump’s campaign has, from the outside, frequently seemed fizzling and unfocused. The former president is juggling distractions in the form of mounting legal troubles and the very real possibility of a criminal indictment. After many of his hand-picked candidates lost in the 2022 midterms, his grip on the GOP was widely proclaimed to be weakening – with even his former vice president apparently gearing up to take him on.

But those factors belie a set of strengths that are in many ways now becoming evident.

As the contours of the 2024 primary battle start to come into focus, Mr. Trump is already benefitting from some of the same circumstances that helped him in 2016. A large, unwieldy Republican field that divides the anti-Trump vote. Opponents too afraid to attack him directly. Above all, a set of diehard fans like Ms. Havill, who are providing him with a solid, unshakeable floor of support.

At the same time, it’s becoming clear Mr. Trump is bringing an entirely different level of political and professional experience to this primary process than in 2016. He’s wooing key officials for endorsements and behind-the-scenes support. And he’s wasting no time building an on-the-ground apparatus with experienced hands in early voting states like Iowa that could give him a significant edge over his GOP rivals – some of whom, like Governor DeSantis, have not even formally entered the race.

“You’d be foolish to underestimate Donald Trump,” says Luke Martz, a Republican strategist based in Iowa.

Some Trump supporters began lining up more than 10 hours in advance of Monday’s event in Davenport, a city in eastern Iowa on the Mississippi River, where Illinois-born Ronald Reagan began his career as a radio sportscaster in the 1930s.

“This isn’t a rally. We’ll be back for a rally soon,” Mr. Trump said, midway through his two-hour speech at a packed theater, in his first visit to the state where the 2024 road to the White House begins for Republicans. As he spoke, volunteers collected names, emails, and addresses from the audience and passed out voter registration forms.

“I said, ‘Why aren’t we doing one at an airport where we can have 50,000 people?’ They said, ‘Sir, it’s too cold.’ That was a good call,” he said, cracking a smile. “Because it’s very cold outside.”

Earlier, Mr. Trump made a brief unannounced stop at a local restaurant where he posed for photos with diners, the kind of retail politicking that Iowans have come to expect. At the theater, he took questions at the end from the audience after joking that the evening should end on a high note, like a concert that ends with a great encore.

In 2016, Mr. Trump famously finished second in the Iowa caucuses behind Texas Sen. Ted Cruz, after a campaign that relied on celebrity and media exposure but fell short on organization. (Mr. Trump conceded but then claimed Senator Cruz “stole” the election.) This time, the former president seems determined not to make the same mistake. Mr. Trump has hired Marshall Moreau, who helped GOP candidate Brenna Bird defeat a 10-term Democratic attorney general in November, to lead his Iowa efforts.

Other hires include state lawmaker Bobby Kaufmann, who appeared on stage with the former president in Davenport. His father, Jeff Kaufmann, a Trump ally, is the chairman of the Iowa Republican Party, leading some Republicans to grumble about a potential conflict of interest in a party-run caucus.

Also on Team Trump: Eric Branstad, whose father Terry Branstad is a popular former Iowa governor who served as Mr. Trump’s ambassador to China. Eric Branstad helped run Mr. Trump’s state campaigns in 2016 and 2020 and is a senior advisor this time.

“Having a strong organizational base in Iowa is really important,” says Doug Gross, a Republican activist here who has been critical of the former president. To win here, campaigns need to be able to convert pledges of support into actual votes on the one night in January – typically a dark, frigid night – that matters.

Mr. Trump’s core of committed supporters, even if they’re a minority, are an enormous asset in a caucus, notes Mr. Gross. “You’ve got to be a pretty committed partisan to go to a caucus and get your voice heard,” he says. “That gives [Mr. Trump] a natural advantage.” But having a campaign that understands the complicated mechanics and rules of caucuses, and can maneuver strategically, can compound that advantage dramatically.

Other Republicans note that the pressure will be on Mr. Trump to win – and to win convincingly – in Iowa, unlike in 2016 when his campaign benefitted from low expectations. Indeed, even a narrow Trump win could be seen as a disappointment, giving momentum to a second-place finisher.

“There’s a big hole for someone to come through,” says David Kochel, an Iowa-based strategist and former advisor to Mitt Romney who helped lead Jeb Bush’s 2016 campaign.

Mr. Trump’s appearance in Iowa came on the heels of a hotly anticipated visit by his putative rival, Governor DeSantis. Mr. DeSantis held two events Friday that were ostensibly to promote his new book but were widely seen as putting down a marker for 2024. He met Republican state lawmakers after his stop in Des Moines, where he was joined by Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds, who also introduced Mr. Trump at his event.

While early national polls often reflect little more than name recognition, the upward trajectory for Mr. DeSantis in states like Iowa seems clear. And his rise in popularity is coming at Mr. Trump’s expense, sharpening the rivalry between the two men, and setting the stage for a potentially drawn-out battle.

An Iowa poll released Friday showed a softening in Mr. Trump’s support, with just 47% of Iowa Republicans saying they would “definitely” vote for him if he’s the GOP nominee, down significantly from 69% in June 2021 (another 27% would “probably” vote for him). The former president’s favorability rating among Iowa Republicans has also declined more than 10 points and is now at 80%, just slightly higher than Mr. DeSantis’ at 75%. (That said, 1 in 5 respondents said they didn’t yet know enough about Mr. DeSantis to assess him.)

“There’s a subset that will be with President Trump no matter what,” says Brett Barker, GOP chairman in Story County. But “I think Iowans in general have an open mind.”

At a recent event in Iowa for defeated Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, former Gov. Branstad told the Monitor that he would remain neutral in 2024. (In 2016, he warned Iowans not to back Senator Cruz over the Texan’s opposition to ethanol subsidies.) But he expressed doubts about Mr. Trump’s chances this time because, he said, the former president has “too much baggage.”

Judging by the responses from Mr. Trump’s supporters, social and cultural grievances will drive the race for the GOP nomination in 2024. The biggest and most sustained applause was for Mr. Trump’s calls to ban transgender athletes from women’s sports, stop the teaching of critical race theory in schools, and “break up” the federal Department of Education.

Mr. Trump seemed to take note. “Look at the hand you get for that,” he said, after the crowd roared its approval. “Bigger than ‘we’re going to be energy independent,’ ” he said, referring to one of his regular applause lines.

By contrast, Mr. Trump’s digs at Florida’s governor – “Ron DeSanctimonious” – received a more muted response. (Mr. DeSantis has so far resisted making direct attacks on the former president.) He said Mr. DeSantis had voted in Congress to cut farm subsidies, and to reduce Social Security and Medicare benefits, both of which Mr. Trump said he would protect.

The president expounded at length on his administration’s record of fighting trade wars with China, Mexico, and Europe, and standing up for farmers in Iowa, including ethanol producers. “I fought for Iowa ethanol like no president in history,” he said.

Outside the theater, some attendees said they would support Mr. DeSantis as a presidential candidate, should he win the nomination instead of Mr. Trump. Others suggested the Florida governor, who is 44, ought to wait his turn.

“I think DeSantis would make a good VP, but Florida needs him right now,” says Roy Nelson, a retiree from Iowa who had traveled from Nevada for the event. “He’s a young man. He has time. This will probably be Trump’s last shot.”

Patterns

As U.S. steps back from Middle East, China steps in

The U.S. has long been the preeminent outside actor in the Middle East. Now China is asserting itself there, stealing Washington's diplomatic thunder. What does this portend?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

Welcome to the post-American Middle East.

That’s the pointed message Iran, Saudi Arabia, and their eager mediator, China, wanted to send Washington with last Friday’s announcement of a Beijing-brokered rapprochement between the region’s rival Muslim powers.

Iran seems to have ditched any intentions of abandoning its nuclear weapons ambitions, and to have thrown in its lot with China.

The Saudis are positioning themselves as a major regional power increasingly independent of Washington.

And for Chinese leader Xi Jinping, the Iran-Saudi deal is part of a grander political vision – that China will ultimately displace the United States as the world’s leading power, by leveraging its economic clout to expand its financial, diplomatic, and military footprints worldwide.

America has been deliberately retreating from its decades-long role as the preeminent outside actor in Mideast affairs, shifting its focus to the challenge China poses. And China, meanwhile, has been focusing on the Middle East.

How might Washington respond to these developments? While President Joe Biden won’t want to reduce the U.S. regional presence any further, he will focus more broadly on China’s challenge to the interests of America and its allies worldwide, in the hope that Washington and Beijing can stabilize their unavoidably competitive relationship.

As U.S. steps back from Middle East, China steps in

Welcome to the post-American Middle East.

That’s the pointed message Iran, Saudi Arabia, and their eager mediator, China, wanted to send Washington with last Friday’s announcement of a rapprochement between the region’s rival Muslim powers.

But America’s retreat from its decades-long role as the preeminent outside actor in Mideast affairs has been a deliberate choice – spurred by a range of factors, not least the disastrous aftermath of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, which began two decades ago next week.

And one irony of China’s Mideast diplomatic breakthrough is that it could dissuade the U.S. from further ceding the significant diplomatic and military weight it still has in the region.

That’s because the main importance of the deal isn’t what it will mean for Iranian-Saudi relations. It’s what the agreement says about the interests and motivations of each of the deal-makers, and the implications for longer-term U.S. interests, in the Middle East and beyond.

First, Iran. Closer than ever to being able to make a nuclear bomb, Tehran seems definitively to have abandoned any notion of a revived agreement with Washington to ease sanctions in return for reimposed nuclear limits. Iran’s leaders are throwing in their lot with China.

Next, Saudi Arabia. Though still dependent on the U.S. for security, the Saudis are positioning themselves as a major regional power increasingly independent of Washington. The trend has accelerated under the kingdom’s de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, amid U.S. criticism of Saudi human-rights violations. Riyadh has been cultivating closer ties with Moscow and now, far more broadly, with Beijing.

The linchpin, however, is China.

For President Xi Jinping, the Iran-Saudi deal is part of a grander political vision, and a nuts-and-bolts example of how he hopes to achieve it.

The vision is that China will ultimately displace the United States as the world’s leading power. The means to achieve it? Leveraging China’s economic clout to expand its financial, diplomatic, and military footprints worldwide.

The Mideast deal also underscores a key pillar of that approach. In explicit contrast to the United States, China is assuring its partners that “internal” issues – such as human rights – are irrelevant to its outreach and alliances.

And while it’s still premature to speak of a “post-American” Middle East, Washington’s reduced sway, and Beijing’s increasing prominence, are evident.

Until earlier this century, America was indisputably the region’s key international power.

It retains strong political, diplomatic, and military ties: with Israel, above all, but also Egypt and Jordan. And, yes, Saudi Arabia and the other states across the Gulf from Iran.

But the U.S. role as mediator in the Arab-Israeli dispute has receded in importance, along with prospects for a two-state compromise to resolve Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians.

The Iraq War dented America’s appetite for direct military involvement. That was made inescapably clear during Syria’s civil war a decade later. President Barack Obama retreated from his “red line” insistence that the U.S. would intervene if President Bashar al-Assad deployed chemical weapons, paving the way for Russian President Vladimir Putin to get involved.

Shale oil, meanwhile, helped free America from dependence on imports from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states. And while still committed to safeguarding Gulf Arab security against Iran, the U.S. sought a diplomatic response to Tehran’s nuclear threat. The result was the nuclear deal, sealed despite deep reservations among U.S. partners in the region.

The overall message they took from the agreement was that Washington was not the engaged, reliable, ally it had long been. Instead, in line with what was being called a “tilt to Asia,” the U.S. was focused on China.

The problem Washington now faces is that China has been focusing on the Middle East.

As China extends its Belt and Road initiative to build infrastructure projects across the developing world, it has made countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia key partners. Where the Saudis once shipped their oil westward, their biggest customer today is China. The same goes for Iran, barred by sanctions from selling its crude elsewhere.

China clearly hopes these economic ties will pave the way for an eventual military presence: a Chinese-built port in Djibouti, at the gateway to Red Sea, became the site of a naval facility in 2017. Beijing has also been investing in port facilities in the Gulf Arab states of Oman and the United Arab Emirates.

The Chinese-brokered Mideast deal raises a policy question for Washington: How should it respond?

Early signs are that, while the U.S. won’t want to reduce its regional presence any further, it will focus more broadly on China’s challenge to the interests of America and its allies worldwide.

While officials publicly shrugged off any suggestion of concern over the Saudi-Iran deal, President Joe Biden joined the leaders of Britain and Australia Monday in publicly sealing the so-called AUKUS partnership to provide Australia with new nuclear-powered submarines as a counterweight to China’s increasingly assertive naval presence.

Where the Middle East is concerned, Mr. Biden will be keen to put some flesh on the bones of his unrealized mantra – that Washington and Beijing have to bring stability, even cooperation, to an unavoidably competitive relationship.

Washington’s hope will be that, with China now reliant on the Gulf for nearly half its oil imports, it, too, will want to avoid the instability and conflict likely if Iran goes fully nuclear.

Congo cease-fire: Displaced residents long for normalcy

Few outsiders know that fighting has forced over 5 million people from their homes in eastern Congo. That lack of attention has allowed their plight to go unresolved for 20 years. A new cease-fire offers only a little hope.

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 5 Min. )

-

By Ryan Lenora Brown Contributor

For Noé Kasali, who lives in war-torn eastern Congo, peace would mean being able to go home each evening and feel safe, as he used to do as a boy.

That is a dream now beyond the reach of more than 5 million people in his part of the world – the number of citizens who have been forced by repeated outbreaks of fighting over the past two decades to flee their homes.

Like most Congolese, Mr. Kasali, now a trauma counselor, puts little faith in the cease-fire that was agreed to last week between the government and the M23 rebel group. After all, it broke down within hours. “People are tired of living every day with broken promises,” he says.

The causes of the violence, which a 23-year United Nations peacekeeping operation has been unable to tame, are complex. They involve ethnic grievances and enormous reserves of valuable minerals, among other factors.

But on the ground in eastern Congo, most people feel far removed from the negotiations brokered by foreign governments, held in distant capitals, to try to restore peace.

Says Mr. Kasali, “They will tell you, the priority of the world is not our lives.”

Congo cease-fire: Displaced residents long for normalcy

Growing up in Oicha, a town in eastern Congo, in the 1990s, Noé Kasali’s playground was his city’s streets. He and his friends stayed out late nearly every night, playing elaborate games in the roads of their neighborhoods as darkness settled over the city. When they went home, their mothers loaded up their plates with plantains, fried beans, and cassava leaves.

Today, when he thinks of what lasting peace would look like in the eastern Congo, this is what he imagines: his children playing under a full moon, or himself coming home with arms full of vegetables from a family plot outside the city.

But when Mr. Kasali heard news last week of a new cease-fire between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) army and a major rebel group, he, like many Congolese, did not get his hopes up.

“People are tired of living every day with broken promises,” says Mr. Kasali, who now runs a trauma counseling center in the eastern city of Beni. And for him, safety has never been about men in a distant conference room in Angola shaking hands and promising to put down their guns. It isn’t soldiers swarming the streets to keep the peace, or 18-wheelers dragging container-loads of rice and cooking oil into displaced persons’ camps.

“It’s about being able to go home,” he says. “People here might be surviving physically, but psychologically, that’s what they’re longing for, to be safe at home.”

According to United Nations figures, 5.8 million people have fled their homes in eastern Congo, forced out by fighting that has stricken the region for over two decades.

Last Tuesday’s cease-fire marked the latest in a series of diplomatic attempts to end the fighting that has been raging for nearly a year in this part of the Congo. But it was broken the same day it went into effect, signaling just how flimsy those efforts have been, particularly for those living in the war’s shadow.

“These security interventions don’t necessarily make people feel safer,” says Margaret Monyani, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa. “The underlying issues aren’t necessarily being dealt with.”

And in eastern Congo, those underlying issues are extremely complex.

Suffering in silence

Since the late 1990s, the region has been buffeted by fighting between the government and dozens of rebel groups, which has killed and uprooted millions. That violence has been fueled, in part, by ethnic grievances that straddle the region’s borders.

The most recent fighting, for instance, is largely between the Congolese army and a rebel group called Mouvement du 23 Mars, or M23, which allegedly receives significant assistance from the government of neighboring Rwanda, according to the U.N. (Rwanda denies providing the group with any support.)

Rwanda’s involvement in Congo dates back to the mid-1990s. Rwanda invaded the DRC, then called Zaire, to hunt down perpetrators of its genocide who had taken refuge there. The conflict spiraled, leading to the overthrow of Zaire’s longtime dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, and plunging the country’s eastern borderlands into violence that continues to this day.

Much of the conflict has been both driven and bankrolled by the country’s enormous deposits of metals such as gold, tin, and tungsten. In 2021, the Norwegian Refugee Council, an international humanitarian agency, found that no other displacement crisis in the world received so little media attention. The Congolese, their report argued, “suffer in a deafening silence.”

M23 is one of about 120 rebel groups to emerge from this instability, which a U.N. peacekeeping force in the region – the longest lasting and most expensive initiative of its kind in the world – has proved unable to tame. Initially formed in 2012, M23 briefly conquered the city of Goma, the regional hub, in November that year. It was effectively defeated by 2013, but in March last year, the group re-formed and began launching new attacks.

Since then, about 600,000 people have fled their homes to escape the fighting. Nearly half of them are now living in makeshift settlements on the outskirts of Goma, relying on precarious humanitarian aid for survival as their crops rot, unpicked in their fields at home.

But even for those who haven’t had to flee, the war has seeped into daily life in ways large and small. In the markets of Goma, for instance, staples of Congolese cuisine – like beans, palm oil, and cassava – are selling for bloated prices because they are in limited supply. Roads in and out of the city are either closed or patrolled by armed rebels, making it nearly impossible for those farmers who are still working to get their goods to market.

Another meeting, another peace deal

Since mid-2022, officials from the DRC, Rwanda, and other countries in the region have met several times to discuss ways to end the fighting. But negotiations have repeatedly broken down, in part because most of the negotiations have not included M23 itself. (M23 leaders said they found out about a cease-fire negotiated in Angola last November on social media.)

Meanwhile, soldiers from a regional East African force deployed to “enforce peace” have been met with widespread skepticism.

“At a very basic level, people want normalcy, not people walking around their cities with expensive guns,” Ms. Monyani, the researcher, says.

Last week, at another meeting in Angola, M23 agreed it would lay down its arms by Tuesday, March 7 at noon. M23 spokesman Lawrence Kanukya told Deutche Welle that the cease-fire would “open the way for direct dialogue with the Kinshasa government.”

But the Tuesday noon deadline for the cease-fire came and went, and fighting continued. On Saturday, the Angolan government said it would send a military unit to the eastern DRC to try to shore up the cease-fire it had brokered.

But doubts persist about the efficacy of such moves.

“I haven’t seen any evidence to think the parties are coming closer to discussing” the problems at the root of the crisis, such as ethnic discrimination against Congolese Tutsis, the group at the core of M23, says Delphin Ntanyoma, a visiting researcher at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam, who studies conflict in the eastern Congo. “The current M23 is an offspring of other rebel insurgencies that claimed to defend the discriminated ethnic Tutsi,” he says.

At his counseling center meanwhile, Mr. Kasali says he often hears people speak wearily of these international attempts to broker peace.

“They will tell you, the priority of the world is not our lives,” he says.

Charting Toni Morrison’s path to creativity

Decorated author Toni Morrison’s approach to creativity involved drawing her settings and jotting inspiration on paper scraps. What does her process tell us about her path toward influencing American culture?

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 4 Min. )

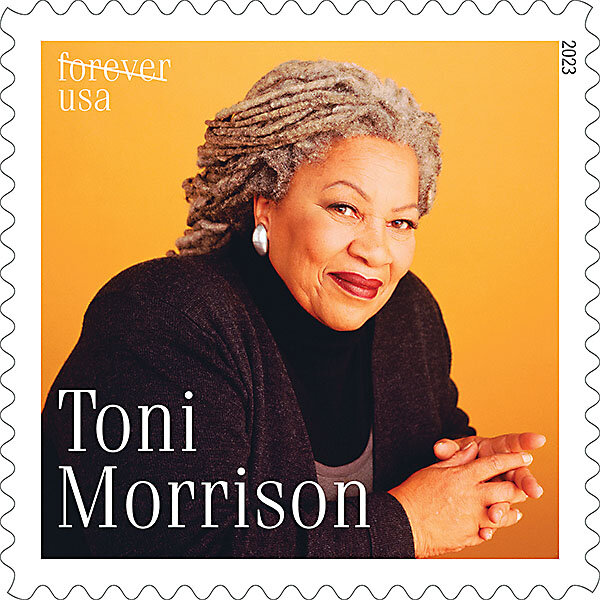

Some school districts are banning Toni Morrison’s books, but Princeton University is celebrating the work of the late author – whose legacy was commemorated this month by the United States Postal Service with a “forever” stamp.

A new exhibit at the school, where Ms. Morrison was a professor, offers a trove of background material on what inspired the Nobel laureate and Pulitzer Prize winner – for “Beloved” – and led to her literary milestones.

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” at Princeton’s Firestone Library through early June, draws on archival material acquired in 2014, including manuscript drafts, sketches, musings, correspondence, and photographs.

“Toni Morrison transformed how we, as a culture, talk about history, slavery, and memory,” says the exhibit’s lead curator, Autumn Womack, via email. “A book like Beloved, for example, created an entirely new framework for thinking about how the past is always haunting us.”

“My hope is that visitors will leave with a sense of Morrison’s creative practice,” adds Dr. Womack.

Ilene Renshaw has traveled from nearby Pennington, New Jersey, to come read the musings of one of her favorite authors. After at least 45 minutes of taking in posted material and watching a video, she is satisfied with making the trip to campus.

“This is a well-deserved celebration,” she says.

Charting Toni Morrison’s path to creativity

Some school districts are banning her books, but a prominent American university is celebrating the canon of work by the late Toni Morrison – who won literature’s highest awards and whose legacy was commemorated this month by the United States Postal Service with a “forever” stamp.

Most people turn to her books, like Pulitzer Prize winner “Beloved,” to better understand the author and the history she depicts. But a new exhibit at Princeton University, where Ms. Morrison was a professor, offers a trove of background material on what inspired the writer and led to her literary milestones.

“Toni Morrison transformed how we, as a culture, talk about history, slavery, and memory,” says the exhibit’s lead curator, Autumn Womack, via email. “A book like Beloved, for example, created an entirely new framework for thinking about how the past is always haunting us.”

“Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory,” at Princeton’s Firestone Library through early June, draws on archival material the university acquired in 2014, including manuscript drafts, sketches, musings, correspondence, photographs, and a taped interview.

“My hope is that visitors will leave with a sense of Morrison’s creative practice, not only what she wrote, but how she wrote, how she moved from what she describes as a question to published masterpiece,” adds Dr. Womack, an assistant professor in the department of English and African American studies at Princeton.

As a working mother to two sons, the author often had to snatch bits of time to formulate story ideas during commutes to and from work. She kept paper handy in the car to write her musings. “If you know it really has come, then you have to put it down,” she once told the Paris Review.

She collected jottings throughout her career. In a note to herself when she was writing her 1992 book, “Jazz,” Ms. Morrison scribbled a reminder to research the first Black police recruit for New York City and when a gun silencer was first available for purchase. A photo of a girl, labeled “Pretty girl in a coffin,” from a Harlem funeral, is featured near her notes for the book.

Words were her main creative material – but she also drew images. Pencil and pen renderings of interior and exterior scenes detail how she envisioned settings. Her sketch of the house in “Beloved,” set in the 1800s, included its store room, cold room, and bathtubs.

“Seeing her original thought process, to me, is fascinating,” says Kristin Eck, on a visit from Denver to see her daughter, who attends Princeton.

Ms. Eck uses words like “raw” and “emotional” to describe Ms. Morrison’s writing. “I’m from the Midwest. Thinking back to when she’s talking about books or writing, and the things that I read growing up, and how much society steered you away from anything that was open. She was open,” she says about the topics the author explored in her fiction.

“The Bluest Eye” is Ms. Morrison’s first novel, published in 1970 and frequently banned for its inclusion of incestuous sexual assault. A typewritten letter from an editor at Doubleday in 1966 urged the writer to continue working on it, but to consider it for short stories instead of a novel. The author’s real-life friend Eunice is the inspiration for the story’s 11-year-old African American main character, Pecola Breedlove, who wishes her eyes could be blue. Descriptions of Eunice come alive in Ms. Morrison’s notes.

“She’s thinking about how to create a character and then how she wants us to read that character,” says Rachel Sturley, a Princeton senior who is visiting the exhibit as part of a presentation for English class on the author’s novel “Song of Solomon.” “So having this context while we’re reading these books and studying in class has been really interesting.”

Ms. Morrison, who was the first African American woman to win a Nobel Prize in literature, says in a filmed interview in the exhibit that her love of reading started in childhood. She explains that even her grandfather – who had no formal education – loved to read and learned by reading the Bible.

Her efforts to publish Black writers such as Toni Cade Bambara and Angela Davis – when she was a senior editor at Random House in the 1970s – shifted the literary landscape and ushered in a new generation, Dr. Womack notes.

“It is hard to overstate the extent to which Morrison influenced American culture,” she explains.

Decades after she was first introduced to Ms. Morrison’s writings, Ilene Renshaw has traveled from nearby Pennington, New Jersey, to come read the musings of one of her favorite authors.

“I have signed first editions [of her books] that I really value,” says Ms. Renshaw, standing near a framed draft of one of Ms. Morrison’s short stories.

She points behind her to a screen where the author is being interviewed and comments on how much she loves her voice because of how distinctive and serene it sounds. After at least 45 minutes of reading through posted material and watching a video, Ms. Renshaw is satisfied with making the trip to campus.

“This is a well-deserved celebration,” she says.

Other headline stories we’re watching

(Get live updates throughout the day.)The Monitor's View

Gender equality as a source of economic renewal

- Quick Read

- Deep Read ( 2 Min. )

-

By the Monitor's Editorial Board

Few countries navigated a more difficult course last year than the island nation of Sri Lanka. It defaulted on its foreign debt. Then food and fuel shortages sparked protests that toppled the government. Inflation peaked at 70%. Yet rather than being prologue to prolonged helplessness, Sri Lanka’s annus horribilis set the stage for a possible model of economic recovery.

The country of 21.6 million people has started to repair confidence with foreign creditors and restore price stability through financial discipline. The International Monetary Fund is expected to approve a $2.9 billion bailout on Monday, which would unlock foreign money for needed infrastructure.

What may be more important is an overhaul of Sri Lanka’s social contract. Last week, the government adopted a plan to uplift women and security. Parliament is working on a gender equality bill.

Sri Lanka’s recovery comes at a time when global lenders are increasingly divided over how to contain a global debt crisis. That underscores the importance of internal reform in debtor nations, where public patience is short.

The IMF’s expected financial assistance will unlock investments in Sri Lanka’s future. But the country’s own investment in equality may ensure the biggest payback.

Gender equality as a source of economic renewal

Few countries navigated a more difficult course last year than the island nation of Sri Lanka. It defaulted on its foreign debt. Then food and fuel shortages sparked protests that toppled the government. Inflation peaked at 70%. Yet rather than being prologue to prolonged helplessness, Sri Lanka’s annus horribilis set the stage for a possible model of economic recovery.

The country of 21.6 million people has started to repair confidence with foreign creditors and restore price stability through financial discipline. The International Monetary Fund is expected to approve a $2.9 billion bailout on Monday, which would unlock foreign money for needed infrastructure. Last week, the United States lauded the government’s commitment to transparency.

What may be more important is an overhaul of Sri Lanka’s social contract. Last week, the government adopted a plan to uplift women and security. Parliament is working on a gender equality bill. In a country where women make up 35% of active workers but only 5% of the national legislature, these measures acknowledge the importance of gender inclusivity to economic health.

“The status of women in the Asian region is not satisfactory,” President Ranil Wickremesinghe said last week. When he announced the gender equality bill in December, he noted that female students account for 50% of higher education enrollment. That represents an undertapped economic resource. “We have a responsibility to increase women’s representation not only in parliament and politics, but in all other areas as well.”

Sri Lanka’s recovery comes at a time when global lenders are increasingly divided over how to contain a global debt crisis. At the end of January, according to the IMF, 28 countries were at high risk of default. A recent meeting of G-20 finance ministers found little agreement on how to solve that. China, the world’s largest lender, remains a key stumbling block. Other major creditors say Beijing’s lack of transparency obstructs coordinating debt leniency or recovery plans.

That underscores the importance of internal reform in debtor nations, where public patience is short. In Sri Lanka, 79% think corruption is rife, according to Transparency International. Freedom House ranks the country as only “partly free” in political freedoms and civil rights. Last week, the government postponed local elections because it could not pay for them.

Institutional reform, economists argue, is vital. But the protest that toppled Mr. Wickremesinghe’s predecessor last year signaled a different kind of renewal already underway.

“There’s really been an awakening of the citizen, from being complacent to dynamic activism with greater agency,” Bhavani Fonseka, a Sri Lankan human rights lawyer, told the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. “This new activism we’re seeing among the citizenry also gives hope that people are being creative in how they hold politicians [and] public officials accountable.”

The IMF’s expected financial assistance will unlock investments in Sri Lanka’s future. But the country’s own investment in equality may ensure the biggest payback.

A Christian Science Perspective

Each weekday, the Monitor includes one clearly labeled religious article offering spiritual insight on contemporary issues, including the news. The publication – in its various forms – is produced for anyone who cares about the progress of the human endeavor around the world and seeks news reported with compassion, intelligence, and an essentially constructive lens. For many, that caring has religious roots. For many, it does not. The Monitor has always embraced both audiences. The Monitor is owned by a church – The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston – whose founder was concerned with both the state of the world and the quality of available news.

The porter

- Quick Read

- Read or Listen ( 3 Min. )

-

By Susan Tish

When we actively welcome thoughts from God, good, into our consciousness, healing is a natural result.

The porter

Recently on a trip to New York City, my daughter and I tried to walk into the lobby of a hotel to have tea in a restaurant there. Before we even got close to the door, a porter standing in front of it stopped and amicably questioned us. Upon learning why we were there, he escorted us to the tea room.

It got me thinking about the role of a porter and an interesting usage of this term in the textbook of Christian Science, “Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,” written by Mary Baker Eddy. She notes the importance of acting as a porter at the door of our thinking: “Stand porter at the door of thought. Admitting only such conclusions as you wish realized in bodily results, you will control yourself harmoniously” (p. 392).

Christ Jesus proved this throughout his healing ministry, and Christ – God’s eternal message of love – is here today to light our path, too. From her in-depth study of the Bible, Mrs. Eddy understood that from God, the divine Mind, we all derive the ability to think and act rightly. As God’s spiritual offspring, reflecting God’s limitless wisdom and love, we are innately able to hear the wise and good thoughts God is constantly communicating.

These good thoughts, or “angel” messages, communicate to us the spiritual facts of existence – of our nature as God’s wholly spiritual, good, and flawless children. They bring peace and comfort, uplift and inspire us, and help us see our permanent safety and well-being in God.

It’s up to us to entertain, or welcome, these angel messages in our consciousness so that they will bless us as God intends. Likewise, we can “close the door” on thoughts and ideas that are not reassuring us of our peace and well-being – we can bar their entry as illegitimate. Thoughts that cause fear, or that seem to challenge our safety, wholeness, worthiness, and peace as God’s children, could not originate from God, divine Love itself, who is infinitely good. Truth, another Bible-based name for God, is here to help us in our role as porters so that we know a true and good idea when we hear it.

One morning a few years ago, while getting dressed, I pulled my shoulder in a strange way and felt a searing pain. I had tweaked my shoulder this way once before, and so the first thought that presented itself to my mental door was, “Oh no. I’ve hurt my shoulder again.”

But right at that moment, it felt as if an angel emissary of Truth, God, stepped right up to the door and presented a better thought: “No. You are not hurt, and you do not need to entertain fear for one more minute.”

Now, that thought felt really good and true! It reminded me of my real identity – not as a mortal susceptible to injury, but spiritual, made by God – and whole, strong, capable, and very good.

Well, as quickly as that original thought was shut out and the spiritual fact welcomed in, the pain left entirely. I was able to handle all the tasks that I needed to do that day, and there has been no more difficulty with my shoulder since.

How wonderful it is to know that any time a thought that doesn’t reflect our God-given goodness and wholeness enters our consciousness, it cannot be from God, and we have the right to shut it out and shut it down. And as we instead let in the true and helpful ideas that God is sending our way at every minute, we naturally experience greater wellness in our life, as well.

Viewfinder

A space oddity

A look ahead

Thanks for joining us. Please come back tomorrow, when we’ll look at how “Vermeer,” a sold-out exhibition in Amsterdam, is a testament to the 17th-century painter’s enormous, ongoing popularity.