The peculiar dinosaurs of Laramidia: weird horns and more

Loading...

Two new species of horned dinosaurs from the vanished continent of Laramidia – now western North American – are creating a buzz.

The creatures' arrangement of horns are unique among the broader group of dinosaurs they belong to, a group that includes animals such as Triceratops.

Moreover, the find appears to lends support to a contentious notion that dinosaurs were quite provincial on Laramidia. The same broad groups of large dinosaurs were present along the north-south reach of the narrow continent, but the species within each broad group differed north and south.

This contrasts with the appearance of large animals in the fossil record from more-recent times. During the last ice age, for example, one could hop into a hypothetical Land Rover, drive from the east coast to the west coast, marvel at the mammoths, mastodons, and giant sloths along the way, and each is "pretty much the same species from the Atlantic coast to the La Brea tar pits," says Thomas Holtz Jr., a paleontologist at the University of Maryland in College Park.

Horns: 'lousy weapons,' but stylish

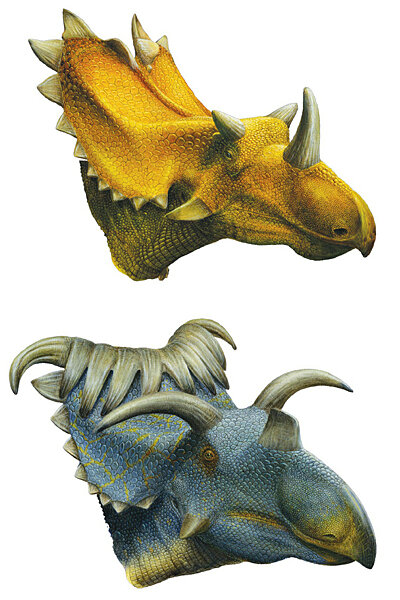

One of the new dinosaurs, dubbed Utahceratops gettyi, not only sported a sizable horn on its nose. It also sprouted small horns protruding from its skull over each eye. Researches estimate that the beast stood about six feet tall at the shoulders, spanned up to 22 feet from nose to tail, and tipped the scales at about 2.5 tons.

Find No. 2, named Kosmoceratops richardsoni, sports a more-bizarre set of horns – 15 in all – that include a long nose horn, eye horns much longer than Utahceratops's, and another 12 along the bony, fan-like "frill" at the back of its skull.

Both animals lived some 76 million years ago, estimates the research team reporting the results this week in the on-line journal PLoS One, published by the Public Library of Science.

The finds come from the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, a rugged patch of southern Utah that represents "one of the country's last great, largely unexplored dinosaur bone yards," says Scott Sampson, a curator at the Utah Museum of Natural History in Salt Lake City, who led the effort.

Between 95 and 68 million years ago, western North America formed a mini-continent, separated from the rest of what was to become North America by a shallow sea that stretched the from Arctic Ocean south to the Caribbean. Mountains dominated much of the continent. But the east coast sported a broad coastal plain where dinosaurs thrived in the warm, humid climate that dominated the planet.

The researchers say the ornate bone structures the two animals displayed likely evolved to attract females and ward off competitors for their attention, rather than for defense.

"Most of these features would have made lousy weapons to fend off predators," Dr. Sampson says.

Why the species stayed put

If dinosaurs on Laramidia were provincial rubes compared with later large animals, the difference might have something to do with food availability, Sampson and his colleagues suggest.

With high temperatures, relatively high carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere, and perhaps a more oxygen-rich atmosphere as well, plants would have thrived in ways that would make a backyard gardener swoon. If plant abundance could support more kilograms of critter on a given patch of land, large numbers of large animals wouldn't need to roam an entire continent to forage for cheap eats.

A variation on that theme suggests that dinosaur metabolism was low enough that they didn't need much food, and so it was easier for them to live off the land they occupied and not wander far afield.

North-south differences in species also could stem from dinosaurs' suspected high fertility compared with comparably large mammals such as rhinos or elephants, Dr. Holtz suggests. While a single pair of large placental mammals might produce one or two offspring every one or two years, a mating pair of dinosaurs could produce eggs by the dozen or two on shorter time scales.

More offspring means fewer parental pairs needed to maintain a viable population.

Whatever the mix of explanations, they don't explain the reason the north-south differences appeared in the first place, Sampson adds. There is no obvious physical barrier that would have separated the populations. And the climate is thought to have been similar enough south to north to rule out dramatic changes in plant types that might present a preferred diet to each broad assemblage of large animals.

The clear species divide in the fossil record "just doesn't make sense at some level," he says.

The lure of Laramidia

Indeed, Holzt says, the real significance of the new finds and the lost continent they come from is that they represent a rapidly growing assemblage of remains that is allowing researchers to delve ever more deeply into evolutionary and environmental changes dinosaurs experienced during their heyday.

As Laramidia evolved, the region hosting the new fossils developed the right combination of ingredients for fossil studies there: volcanic activity that can supply the radioactive elements for precise dating of fossil beds; mountain-building and erosion to supply the sediment to entomb the animals and preserve their fossils; and relatively little rain to destroy them. All in a location relatively easy for paleontologists to reach.

That combination of things make the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument "a really good spot for finding a succession of dinosaur faunas," Holtz says.