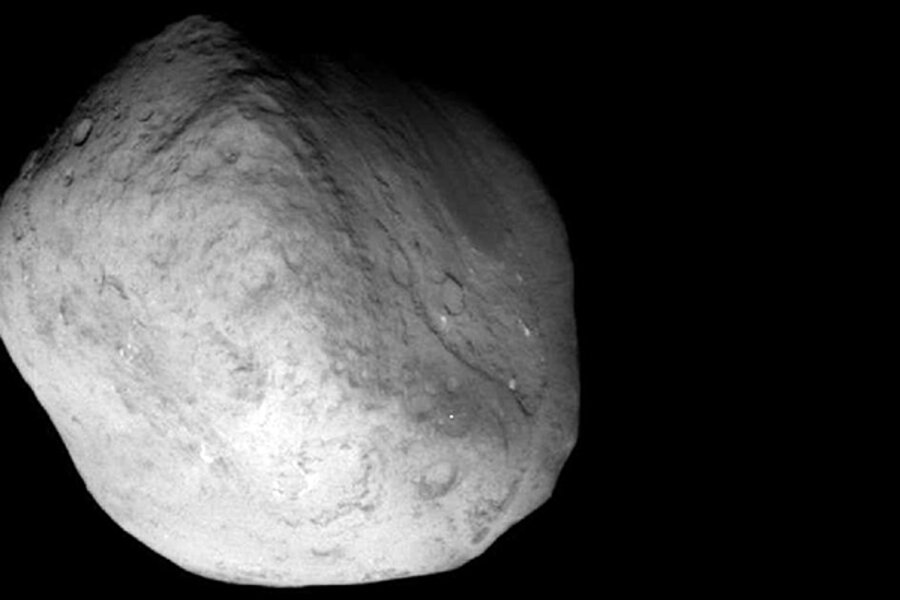

72 new images of comet Tempel 1 streaming in from Stardust-NExT flyby

Images taken during the Stardust-NExT mission's flyby of comet Tempel 1 Monday night are trickling in to a happy but bleary-eyed science team eager to comb them for clues about the comet's history and changes the comet may have undergone since 2005, when another spacecraft took its measure.

After a trip of slightly more than 5.3 billion miles since its launch in February 1999, Stardust-NExT sped to within 112 miles of the comet, snapping 72 images during the flyby.

It's the first time researchers have gathered flyby data on the same comet twice.

Since 2005, Tempel 1 has orbited the sun once, giving researchers an unprecedented opportunity to see firsthand the effect a comet's close approach – in this case, no closer to the sun than the orbit of Mars – has on the comet's surface.

That information not only helps researchers understand how comets evolve with time. It also is vital to planning future comet sample-return missions that involve landers, says Joseph Veverka, a Cornell University researcher and the Stardust-NExT mission's lead scientist.

Comets are thought to carry pristine material left over from the formation of the solar system some 4.5 billion years ago. But with each swing past the sun, a comet's surface changes as it warms and releases dust, ice, and gas.

Data from Stardust-NExT will help scientists identify newly exposed material from older, more processed material as they try to pick landing spots on a comet's nucleus, Dr. Veverka explains.

The first encounter with Tempel 1 involved NASA's Deep Impact mission, which sent an impactor hurtling into Tempel 1's nucleus.

Much can be gleaned about the nucleus's structure and composition by analyzing the crater, researchers say. Unfortunately, the impact kicked up so much dust that the Deep Impact craft couldn't see it during its brief encounter.

The hope is that Stardust-NExt, in addition to imaging more of Tempel 1's surface, might also capture images of the crater.

By 11:59 p.m. Eastern Standard Time on Valentine's Day, controllers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) received confirmation from the Stardust-NExT craft that it had completed its closest approach 20 minutes earlier, slightly closer than the team initially thought it would reach.

From a hardware standpoint, "everything worked perfectly," said Veverka. Controllers confirmed that the images all were centered in the field of view of the craft's camera, which snapped 72 images during the flyby. The closest image was taken when the craft was 113 miles from the comet's nucleus.

The research team expected five images that bracketed the closest approach to be the first they would see, appearing on their screens some three hours after closest approach. But Stardust-NExT had other ideas.

"We sent the commands we had planned, anticipating that the middle five images would be played back," says Chris Jones, associate director for flight projects and mission success at JPL. Instead, "we went to the top of the stack and the first picture we received was the first image" in the 72-image sequence.

He estimated that researchers would have to wait until about 10 a.m. EST to receive the five images they are the most eager to study.