Space junk: Where will out-of-control satellite crash? Probably not on you.

Loading...

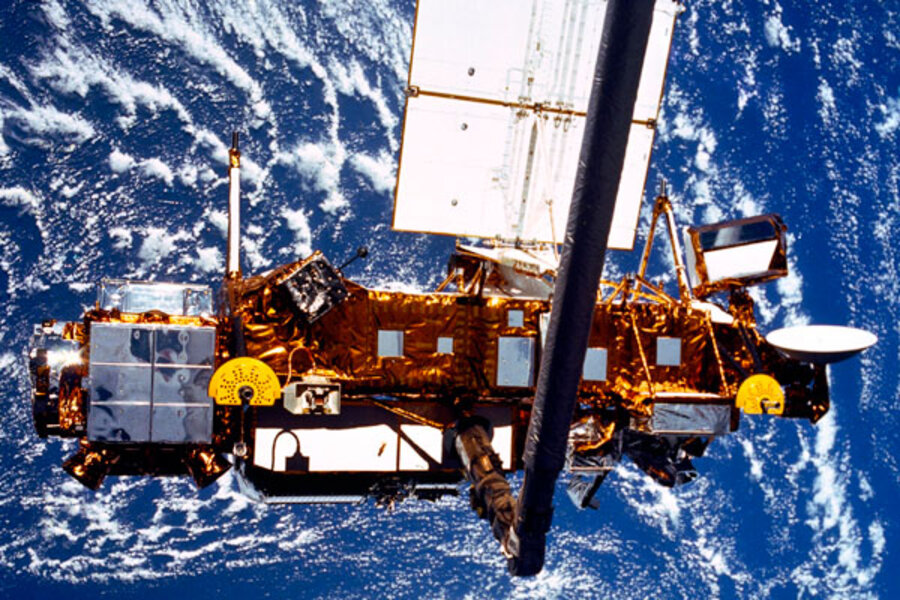

After 20 years in space, a 6.5-ton NASA spacecraft is expected to return to Earth as early as this afternoon.

With no fuel left in the satellite's tanks, controllers have had no opportunity to tweak its orbit to guide it to an ocean splashdown. It's charting its own path.

While 26 chunks of debris are expected to survive the fiery reentry, the danger surviving debris poses to anyone on the planet is vanishingly small, specialists say.

Falling toward a planet where the ocean makes up 71 percent of the surface, the debris stands a 1-in-2,300 chance of striking anyone at all somewhere on Earth, according to NASA risk estimates. That means the chances of it hitting any specific person – like you – is reportedly about 1 in 21 trillion.

By contrast, the chance of being struck by lightning is 1 in 280,000.

NASA's latest estimate for reentry suggests the craft will make its final plunge between late today and early Saturday, Eastern time. The exact time and location of reentry is still too uncertain to predict, but NASA says the probability is low that any debris will hit the continental US.

Regardless, the event highlights the need to have end-of-mission plans for satellites so that once it's mission ends it poses no threat to people on the reentry or to other craft if it remains on orbit.

[ Video is no longer available. ]

Spacefaring nations have made progress in responding to that challenge. Many of them agreed on a set of "best practices" guidelines in 2002. In 2008, the UN accepted similar guidelines.

The guidelines are voluntary, but "several countries – the US, France, Japan, Russia, Germany, and others – have put in place national laws" to implement the guidelines, says Brian Weeden, technical adviser to the Secure World Foundation, an organization that aims to foster sustainable use of space.

But the rain of debris continues, driven by the breakup and orbital decay of missions past. Last year nearly 400 objects larger about four inches across – from chunks of collision debris to spent rocket boosters – reentered the atmosphere. All but about a 13 or 14 of them were uncontrolled, Mr. Weeden says.

NASA space-debris specialists estimate that, on average, one object about the size, if not the mass, of the agency's current wayward spacecraft enters the atmosphere each year – typically a spent rocket stage.

The largest spacecraft to reenter the atmosphere in an uncontrolled manner was Skylab, the first US space station. Tipping the scales at 76 tons, Skylab broke up on reentry in 1979, spreading its debris along a 280-mile stretch of western Australia.

When NASA designed, built, and launched the current craft, the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), international law already had resolved liability issues surrounding uncontrolled re-entry. The rule was simple: The launch country is liable for any damage to aircraft in flight or to anything or anyone on the ground, Mr. Weeden notes.

But the UARS craft was designed, built, and launched before the spacefaring nations adopted the guidelines to reduce space junk.

But when the mission ended in 2005, NASA tried to acknowledge the guidelines by lowering the craft's orbit – a maneuver that would allow the craft to descend into Earth's atmosphere and break up earlier than it otherwise would have done. The goal was to prevent it from becoming space junk. But the maneuver drained the craft's fuel supply, leaving controllers with nothing in the tanks to make final adjustments to ensure a reentry over the ocean.

And so, the world watches to see whether satellite shards expected to survive UARS's reentry litter the landscape or quench their heat in salt water.