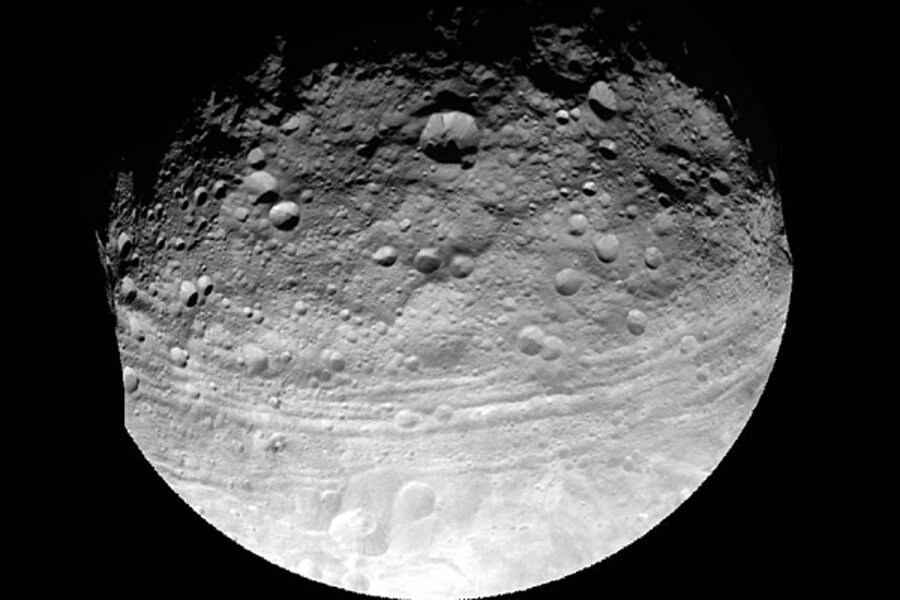

New images of protoplanet Vesta reveal mountain bigger than Everest

Loading...

The protoplanet Vesta, once a fuzzball in telescopic images, is revealing a surprising range of features – from a mountain with a rise three times higher than Mt. Everest's to a puzzling band of deep, wide, and long troughs gouged into Vesta's surface.

These are among the highlights from an initial look planetary scientists are getting at Vesta via NASA's Dawn mission. The researchers described their observations on Wednesday at a meeting of the Geological Society of America in Minneapolis.

Launched Sept. 27, 2007, Dawn arrived at Vesta last July and is lingering for a year's worth of observations before moving on to another, equally intriguing object, Ceres.

Both Vesta and Ceres orbit the sun between Mars and Jupiter among an assemblage of construction rubble known as main-belt asteroids – leftovers from the early, heady days of planet formation in some 4.5 billion years ago.

But Vesta and Ceres attained a stature asteroids didn't. The two objects are considered protoplanets. They acquired enough mass to undergo processes that led to subsurface redistribution of material based on density – a process known as diferentiation and one milestone during the transition from a ball of cosmic rubble to a planet.

The duo's growth, however, was stunted – frozen in time – by gravity from a rapidly bulking Jupiter. Thus, researchers hold that Vesta and Ceres can provide unique insights on an important stage of planet formation that until now has been the province of computer models.

Hubble Space Telescope images of Vesta, as fuzzy as they are, still point to an object with variations in minerals across the surface and hint at interesting features on its surface, notes Carol Raymond, the deputy lead scientist for the Dawn mission.

As the research team pored over images the craft has taken since it arrived, it was clear Vesta's variety has been generated by more than material ejected and spread over the surface by periodic collisions with other objects.

"We have strong structural features that have been preserved over billions of years. We have apparent layering of the surface. The degree to which Vesta appears to have preserved a geologic record is something that's very thrilling," Dr. Raymond says. "It's a small world that's quite unique."

The northern half of Vesta is relatively old and heavily cratered, she explains. But the southern half? It's looking like a planetary geologist's dream, members of the science team suggest.

Perhaps Vesta's most striking feature is an enormous impact basin at its south pole, notes Paul Schenk, a researcher at the Lunar and Planetary Institute in Houston and a member of Dawn's science team.

Hints of something unusual there appear in Hubble images taken in the late 1990s.

Now it appears the feature might qualify as one of the Seven Wonders of the Solar System. The basin is nearly 300 miles across and between 12 and 15 miles deep. In its center sits the asteroid belt's version of Mt. Everest – a mountain whose base spans just over 100 miles and whose summit soars an average of about 13 miles above the surrounding terrain.

"It's one of the deepest impact craters we've seen in the solar system," he says, adding that it hosts one of the biggest mountains yet found in the solar system.

As if that wasn't enough to suggest Vesta had a rough childhood, the impact basin, dubbed Rhea Silvia, sits atop an older basin of somewhat smaller diameter. "We didn't expect this," Dr. Schenk says, noting that the team has also identified several other, older impact basis north of Rhea Silvia.

One reason the basins are of interest: Researchers hold that meteorites exhibiting a wide range of ages known as HED meteorites come from Vesta. Scientists hope to be able to associate these with some of the impact features they see on Vesta.

Vesta has adorned its surface with another puzzle: long, parallel troughs that look as though some giant held the protoplanet in one hand, turned it slowly, then repeatedly allowed its fingertips to trace the pattern along Vesta's equator.

The troughs have steep, scarp-like walls, flat floors up to 15 miles wide, and stretch up to two-thirds of the way around the sphere.

Vesta's northern hemisphere boasts troughs as well, although they appear more time-worn, says Debra Buczkowski, a planetary geologist at the Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Md. One of these is roughly 24 miles wide.

As if to underscore Vesta's in-between status, she notes that in some ways the fractures "are behaving like the fractures we would expect on an asteroid. But the sheer scale of them is more similar to what we would see on a planet."

In many ways, these observations are warm-ups. Dawn's instruments carried out these and other measurements during a 21-day survey phase, orbiting some 1,700 miles above Vesta. The craft has now dropped to a 420-mile-high orbit and will begin its lowest-altitude passes – less than 110 miles up – in December.

With each step down the orbital ladder toward Vesta, researches say they expect more remarkable surprises as they map its topography and the minerals it holds.