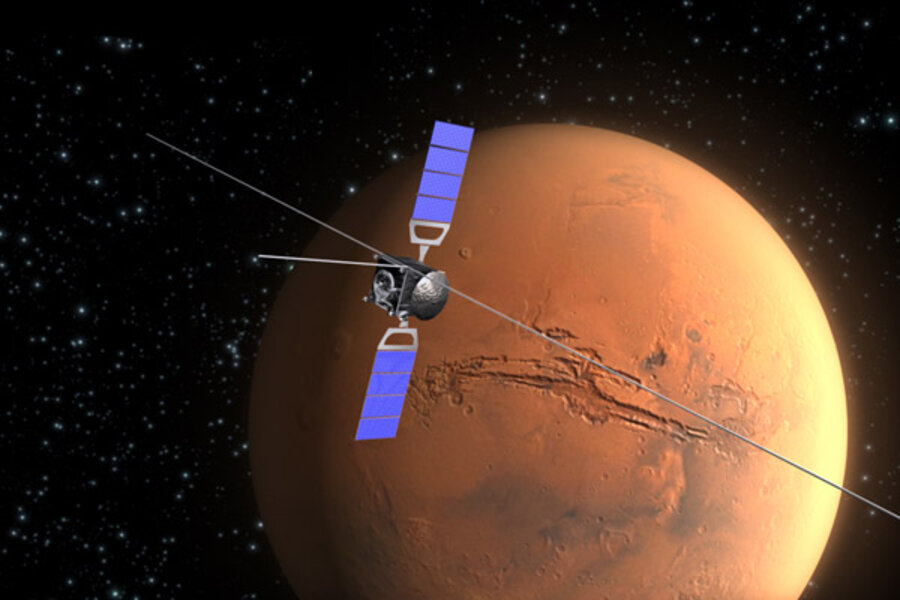

ESA Mars probe finds evidence of ancient Martian ocean

Loading...

A European spacecraft orbiting Mars has found more revealing evidence that an ocean may have covered parts of the Red Planet billions of years ago.

The European Space Agency's Mars Express spacecraft detected sediments on Mars' northern plains that are reminiscent of an ocean floor, in a region that has also previously been identified as the site of ancient Martian shorelines, the researchers said.

"We interpret these as sedimentary deposits, maybe ice-rich," study leader Jérémie Mouginot, of the Institut de Planétologie et d'Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG) in France and the University of California, Irvine, said in a statement. "It is a strong new indication that there was once an ocean here."

As part of its mission, Mars Express uses a radar instrument, called MARSIS, to probe beneath the Martian surface and search for liquid and solid water in the upper portions of the planet's crust.

The researchers analyzed more than two years of MARSIS data and found that the northern plains of Mars are covered in low-density material that suggests the region may have been an ancient Martian ocean. [Photos: Red Planet Views from Europe's Mars Express]

"MARSIS penetrates deep into the ground, revealing the first 60–80 meters of the planet's subsurface," said Wlodek Kofman, leader of the radar team at IPAG. "Throughout all of this depth, we see the evidence for sedimentary material and ice."

The idea of oceans on ancient Mars is hardly new, and features reminiscent of shorelines have been tentatively identified in images from various spacecraft and missions. Still, the concept remains controversial.

In fact, this new investigation comes on the heels of a separate study that found that Mars may have experienced a "super-drought," making it parched for too long for life to exist on the surface of the planet today.

But, scientists working to document Mars' history have proposed two oceans: one 4 billion years ago when the planet experienced a warmer and wetter period, and one 3 billion years ago when subsurface ice melted after a large impact that created various channels that drained water into areas of lower elevation, the researchers said.

Still, the more recent ocean would have only been a temporary feature on the Martian surface, the researchers said. The water would likely have been frozen or preserved underground again, or turned into vapor and lifted gradually into the atmosphere within a million years or less, Mouginot explained.

"I don't think it could have stayed as an ocean long enough for life to form," Mouginot said in a statement.

The sediments seen by Mars Express are typically low-density grains of material that have been eroded away by water and carried off to their current location. According to the researchers, the MARSIS instrument reveals the sediments to be areas of low radar reflectivity.

In the ongoing search for life on Mars, astrobiologists will likely have to delve deeper into the Martian past, when liquid water may have existed for longer periods on the surface, the scientists said.

Still, these results are some of the best evidence yet that there were once large bodies of liquid water on the surface of Mars, the researchers said. The findings are also further proof that liquid water likely played an important role in the geological history of Mars, and the planet's own evolution.

"Previous Mars Express results about water on Mars came from the study of images and mineralogical data, as well as atmospheric measurements," Olivier Witasse, a Mars Express project scientist at the European Space Agency, said in a statement. "Now we have the view from the subsurface radar. This adds new pieces of information to the puzzle but the question remains: where did all the water go?"

Mars Express was launched in June 2003 and entered orbit around the Red Planet in December 2003. The spacecraft is scheduled to operate until at least the end of 2012.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.