Ice, ice baby: Old arctic ice disappearing faster than younger thin ice

Loading...

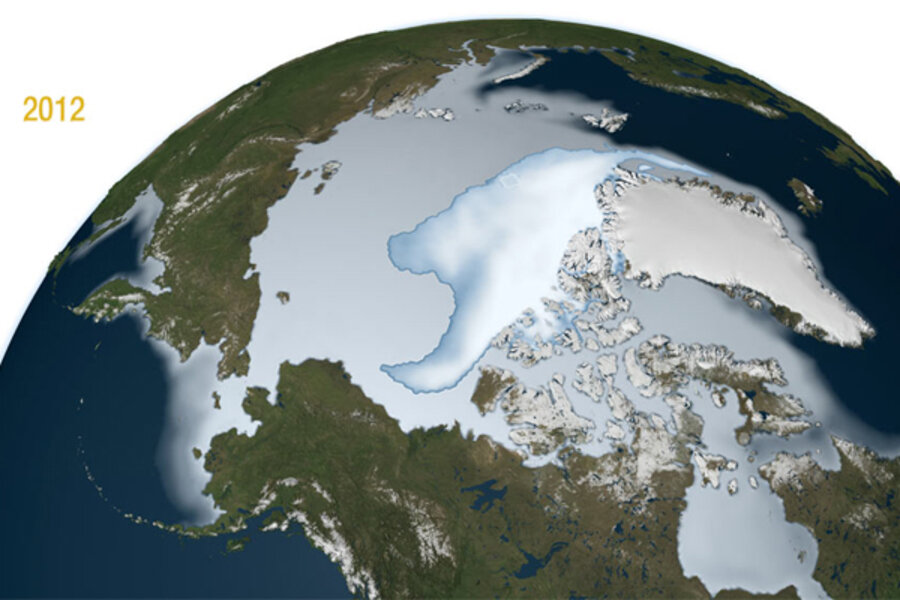

The oldest and thickest Arctic ice seems to be vanishing faster than the younger, thinner ice at the edges of the Arctic Ocean's floating ice cap, a new NASA study finds.

Typically the thicker, older ice survives through the summer melt season (hence, it's called multi-year ice), while the younger ice that forms over the winter melts as quickly as it formed. That's what makes this new finding worrisome; if the ice that usually sticks around is rapidly disappearing, the Arctic sea ice is more vulnerable to further disappearance during the summer, said study researcher Joey Comiso, senior scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

In the new study, Comiso and colleagues looked at multi-year ice that had made it through at least two summers. They wanted to see how it diminished with each passing winter over the past three decades. Results showed that the extent of multi-year ice, which includes areas of the Arctic Ocean where multi-year ice covers at least 15 percent of the water's surface, is shrinking at a rate of 15.1 percent per decade.

They found more disturbing results when looking at the "area" of the multi-year ice, which includes exclusively regions of the Arctic Ocean that are completely covered by multi-year ice. This sea-ice area is always smaller than sea-ice extent. They found that multi-year ice area is shrinking even faster than multi-year ice extent, by 17.2 percent per decade. [Gallery: Vanishing Glaciers]

"The average thickness of the Arctic sea ice cover is declining because it is rapidly losing its thick component, the multi-year ice. At the same time, the surface temperature in the Arctic is going up, which results in a shorter ice-forming season," Comiso said in a NASA statement. "It would take a persistent cold spell for most multi-year sea ice and other ice types to grow thick enough in the winter to survive the summer melt season and reverse the trend."

Multi-year sea ice hit its record minimum extent in the winter of 2008, when the ice was reduced to about 55 percent of its average extent since the late 1970s, the time when satellite measurements of the ice cap began. The extent of multi-year sea ice then recovered slightly in the three following years, ultimately reaching an extent 34 percent larger than in 2008, the study found. But it dipped again in winter of 2012, to its second lowest extent ever, the researchers report in a recent issue of the Journal of Climate.

The researchers used data collected by NASA's Nimbus-7 satellite and the U.S. Department of Defense's Defense Meteorological Satellite Program to create a time series of multi-year sea ice. The salt content distinguishes the two types of ice: Younger ice, formed from recently frozen ocean water, is saltier than the multi-year type, which loses its salts over time. The level of saltiness changes the ice's electrical properties, causing the ice to different levels of radio waves in the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum. The microwave radiometers on the Nimbus-7 satellite pick up these differences.