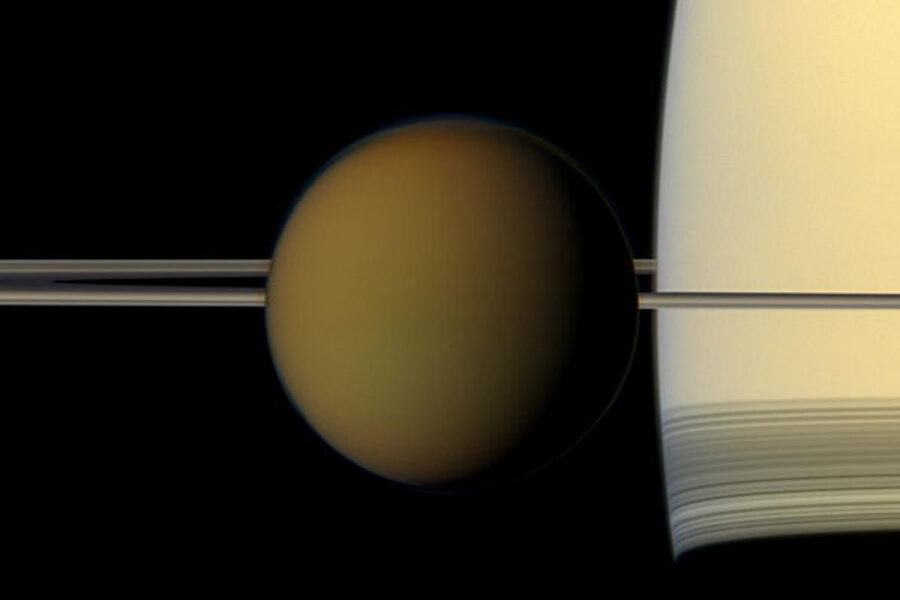

Life on Saturn moon? Discovery of hidden ocean on Titan tantalizes.

Loading...

A global ocean appears to lurk miles beneath the surface of Saturn's moon Titan, adding to the allure of an object rich with the building blocks of organic life and often likened to Earth before life emerged.

Cassini has already found large lakes – most likely made of hydrocarbons such as liquid methane – on Titan's surface. But a team of scientists using NASA's Cassini spacecraft have now found indirect but telltale signs of a subsurface sea, perhaps of water as well as ammonia, which would act like antifreeze.

The data suggest that the ocean, perhaps more than 15 miles deep, is sandwiched between two layers of ice, each less than 60 miles (100 kilometers) thick. It rides atop one layer of ice covering the moon's rocky core and appears to be capped with another ice layer that forms Titan's surface.

Titan has captured the imagination of scientists hunting for potential habitats for simple forms of life for decades. The temperature at Titan's surface is unbearably cold, minus 290 degrees Fahrenheit. It is paved with the methane ices and other organic solids on which Cassini's Huygens probe landed on Jan. 14, 2005. Its atmosphere is thought to mirror the composition of Earth's atmosphere before the emergence of life some 3.8 billion years ago.

As hostile as the surface seems to be, "liquids from below would enhance the possibility of life being on the surface" as well as enhancing the possibility of aquatic habitats deep beneath Titan's crust, says Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at Washington State University in Pullman with a keen interest in Titan's potential habitability.

Thursday's report represents "a nice step forward" in establishing an ocean's presence on Titan, he says.

The new finding adds Titan to the growing list of moons thought to have subsurface oceans. The icy surface of Jupiter's Europa is believed to hide a vast ocean, and data from Cassini suggest a large, if not global, region of water or slush under the icy sheath of Saturn's Enceladus. Neptune's moon Triton may also have a subsurface ocean, and Ganymede and Callisto, two more Jovian moons, also are though to have under-ice seas.

But Titan stands out because researchers know that organic compounds are abundant there.

Researchers led by Luciano Iess, a scientist at the Universita La Sepienza in Rome, used radio signals from Cassini to track changes in the effect Titan's gravity has on the orbiter during flybys. These readings allow the team to measure the strength of Titan's gravity in the regions Cassini overflies.

This process allows researchers to "weigh the moon, basically," says Sami Asmar, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., and a member of the team that reported its results on Sciencexpress, the web outlet of the journal Science.

If Titan was solid, its gravity field wouldn't change. Even when the moon comes closest to Saturn on its elliptical orbit – experiencing Saturn's strongest tug – its mass would remain fairly evenly distributed throughout the object.

But Titan's gravity changes as it progresses along its orbit, the team found. The side of the moon that always faces Saturn bulged as Titan made its closest approach to the ringed planet.

"We caught Titan in the act of deforming," Mr. Asmar says.

This tidal bulge represents a redistribution of material within the moon's interior – a telltale sign that there is likely a fluid layer in the moon's interior.

It is as though Titan's rocky core with its icy cover was being drawn through the global subsurface ocean toward Jupiter as the moon made its closest approach, creating the bulge.

The friction of the moon's tidal interaction with Saturn generates heat, which could help sustain the ocean's liquid state – as is the case within Enceladus and Europa.

The observation of a global ocean beneath Titan's icy exterior is indirect, Asmar says, "But it's real evidence."

[Editor's note: This article has been updated to correct Sami Asmar's title.]