NASA's $2.5 billion Mars rover faces tricky landing

Loading...

| Pasadena, Calif.

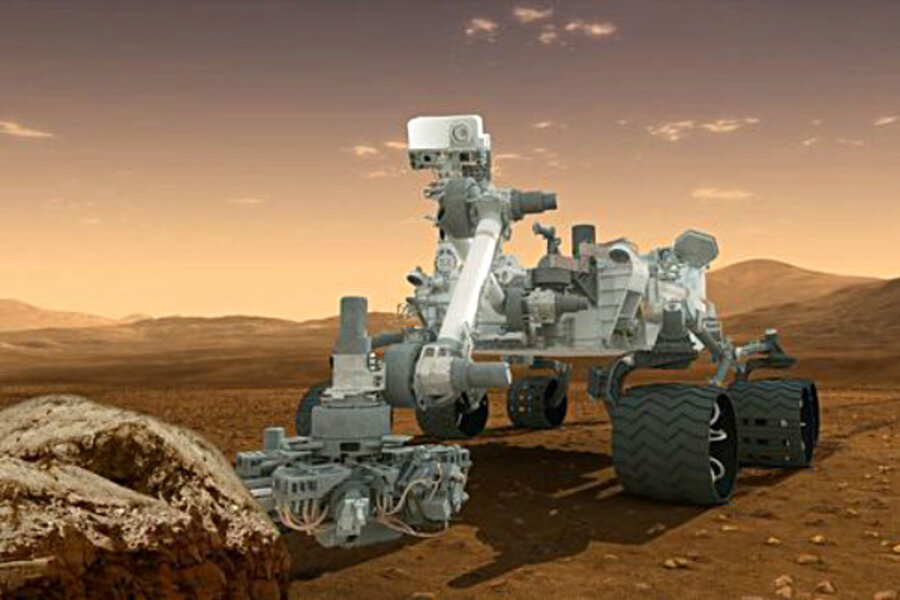

It's the U.S. space agency's most ambitious and expensive Mars mission yet — and it begins with the red planet arrival Sunday of the smartest interplanetary rover ever built.

It won't be easy. The complicated touchdown NASA designed for the Curiosity rover is so risky it's been described as "seven minutes of terror" — the time it takes to go from 13,000 mph (20,920 kph) to a complete stop.

Scientists and engineers will be waiting anxiously as the spacecraft plunges through Mars' thin atmosphere and, in a new twist, attempts to slowly lower the rover to the bottom of a crater with cables.

Scientists on Earth won't know for 14 minutes whether Curiosity lands safely as radio signals from Mars travel to Earth.

If it succeeds, a video camera aboard the rover will have captured the most dramatic minutes for the first filming of a landing on another planet.

"It would be a major technological step forward if it works. It's a big gamble," said American University space policy analyst Howard McCurdy.

The future direction of Mars exploration is hanging on the outcome of this $2.5 billion science project to determine whether the environment was once suitable for microbes to live. Previous missions have found ice and signs that water once flowed. Curiosity will drill into rocks and soil in search of carbon and other elements.

Named for the Roman god of war, Mars is an unforgiving planet with a hostile history of swallowing man-made spacecraft. It's tough to fly there and even tougher to touch down. More than half of humanity's attempts to land on Mars have ended in disaster. Only the U.S. has tasted success.

"You've done everything that you can think of to ensure mission success, but Mars can still throw you a curve," said former NASA Mars czar Scott Hubbard, who now teaches at Stanford University.

The Mini Cooper-sized spacecraft traveled eight and a half months to reach Mars. In a sort of celestial acrobatics, Curiosity will twist, turn and perform other maneuvers throughout the seven-minute thrill ride to the surface.

Why is NASA attempting such a daredevil move? It had little choice. Earlier spacecraft dropped to the Martian surface like a rock, swaddled in airbags, and bounced to a stop. Such was the case with the much smaller and lighter rovers Spirit and Opportunity in 2004.

At nearly a ton, Curiosity is too heavy, so engineers had to come up with a new way to land. Friction from the thin atmosphere isn't enough to slow down the spacecraft without some help.

During its fiery plunge, Curiosity brakes by executing a series of S-curves — similar to how the space shuttle re-entered Earth's atmosphere. At 900 mph (1,450 kph), it unfurls its huge parachute. It then sheds the heat shield that took the brunt of the atmospheric friction and switches on its ground-sensing radar.

Curiosity then jettisons the parachute and fires up its rocket-powered backpack to slow it down until it hovers. Cables unspool from the backpack and slowly lower the rover — at less than 2 mph (3.2 kph). The cables keep the rocket engines from getting too close and kicking up dust.

Once the rover senses touchdown, the cords are cut.

Even if the intricate choreography goes according to script, a freak dust storm, sudden gust of wind or other problem can marthe landing.

"The degree of difficulty is above a 10," said Adam Steltzner, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which manages the mission.

The rover's landing target is Gale Crater near the Martian equator. Scientists know Gale was once waterlogged. Images from space reveal mineral signatures of clays and sulfate salts, which form in the presence of water, in older layers near the bottom of the mountain.

During its two-year exploration, the plutonium-powered Curiosity will climb the lower mountain flanks to probe the deposits. As sophisticated as the rover is, it cannot search for life. Instead, it carries a toolbox including a power drill, rock-zapping laser and mobile chemistry lab to sniff for organic compounds, considered the chemical building blocks of life. It also has cameras to take panoramic photos.

Humans have been mesmerized by Mars since the 19th century when American astronomer Percival Lowell, peering through a telescope, theorized that intelligent beings carved what looked like irrigation canals. Scientists now think that if life existed onMars — a big if — it would be in the form of microbes.

Curiosity will explore whether the crater ever had the right environment for microorganisms to take hold.

___